Structural analysis of a clockwise-biased rotation mutant of the bacterial flagellar rotor protein FliG provides a new model for the arrangement of FliG subunits in the motor, and novel insights into rotation switching.

Abstract

The bacterial flagellar motor can rotate either clockwise (CW) or counterclockwise (CCW). Three flagellar proteins, FliG, FliM, and FliN, are required for rapid switching between the CW and CCW directions. Switching is achieved by a conformational change in FliG induced by the binding of a chemotaxis signaling protein, phospho-CheY, to FliM and FliN. FliG consists of three domains, FliGN, FliGM, and FliGC, and forms a ring on the cytoplasmic face of the MS ring of the flagellar basal body. Crystal structures have been reported for the FliGMC domains of Thermotoga maritima, which consist of the FliGM and FliGC domains and a helix E that connects these two domains, and full-length FliG of Aquifex aeolicus. However, the basis for the switching mechanism is based only on previously obtained genetic data and is hence rather indirect. We characterized a CW-biased mutant (fliG(ΔPAA)) of Salmonella enterica by direct observation of rotation of a single motor at high temporal and spatial resolution. We also determined the crystal structure of the FliGMC domains of an equivalent deletion mutant variant of T. maritima (fliG(ΔPEV)). The FliG(ΔPAA) motor produced torque at wild-type levels under a wide range of external load conditions. The wild-type motors rotated exclusively in the CCW direction under our experimental conditions, whereas the mutant motors rotated only in the CW direction. This result suggests that wild-type FliG is more stable in the CCW state than in the CW state, whereas FliG(ΔPAA) is more stable in the CW state than in the CCW state. The structure of the TM-FliGMC(ΔPEV) revealed that extremely CW-biased rotation was caused by a conformational change in helix E. Although the arrangement of FliGC relative to FliGM in a single molecule was different among the three crystals, a conserved FliGM-FliGC unit was observed in all three of them. We suggest that the conserved FliGM-FliGC unit is the basic functional element in the rotor ring and that the PAA deletion induces a conformational change in a hinge-loop between FliGM and helix E to achieve the CW state of the FliG ring. We also propose a novel model for the arrangement of FliG subunits within the motor. The model is in agreement with the previous mutational and cross-linking experiments and explains the cooperative switching mechanism of the flagellar motor.

Author Summary

The bacterial flagellum is a rotating organelle that governs cell motility. At the base of each flagellum is a motor powered by the electrochemical potential difference of specific ions across the cytoplasmic membrane. In response to environmental stimuli, rotation of the motor switches between counterclockwise and clockwise, with a corresponding effect on the swimming direction of the cell. Switching is triggered by the binding of the signaling protein phospho-CheY to FliM and FliN, and achieved by conformational changes in the rotor protein FliG. The actual switching mechanism, however, remains unclear. In this study, we characterized a fliG mutant of Salmonella that shows an extreme clockwise-biased rotation, and determined the structure of a fragment of FliG (FliGMC) of the equivalent mutant variant of Thermotoga maritima. FliGMC is composed of two domains and covers the regions essential for torque generation and FliM binding. We showed that the mutant structure has a conformational change in the helix connecting the two domains, leading to a domain orientation distinct from that of the wild-type FliG. On the basis of this structure, we propose a new model for the arrangement of FliG subunits in the rotor that is consistent with the previous mutational studies and explains how cooperative switching occurs in the motor.

Introduction

Bacteria such as Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica swim by rotating multiple flagella, which arise randomly over the cell surface. Each flagellum is a huge protein complex made up of about 30 different proteins and can be divided into three distinct parts: the basal body, the hook, and the filament. The basal body is embedded in the cell envelope and acts as a reversible motor powered by a proton motive force across the cytoplasmic membrane. The hook and the filament extend outwards in the cell exterior. The filament is a helical propeller that propels the cell body. The hook connects the basal body with the filament and functions as a universal joint to transmit torque produced by the motor to the filament. The flagellar motor can exist in either a counterclockwise (CCW) or clockwise (CW) rotational state. CCW rotation causes the cell to swim smoothly in what is termed a run, whereas brief CW rotation of one or more flagella causes a tumble. The direction of motor rotation is controlled by environmental signals that are processed by a sensory signal transduction pathway to generate chemotaxis behavior [1]–[3].

Five flagellar proteins, MotA, MotB, FliG, FliM, and FliN, are involved in torque generation. Two integral membrane proteins, MotA and MotB, form the stator, which converts an inwardly directed flux of H+ ions through a proton-conducting channel into the mechanical work required for motor rotation. The FliG, FliM, and FliN proteins form the C ring on the cytoplasmic side of the MS ring, which is assembled from 26 subunits of a single protein, FliF, and this complex acts as the rotor of the flagellar motor [1]–[3]. An electrostatic interaction between the cytoplasmic loop of MotA and FliG is thought to be involved in torque generation [4],[5] and in stator assembly around the rotor [6]. The protonation-deprotonation cycle of a highly conserved aspartic acid residue in MotB is coupled to the movement of the MotA cytoplasmic loop to generate torque [7]–[9].

Because FliG, FliM, and FliN are also responsible for switching the direction of motor rotation, their assembly is called the switch complex [10]. Binding of a chemotactic signaling protein CheY-phosphate (CheY-P) to FliM and FliN is presumed to induce conformational changes in FliG that result in a conformational rearrangement of the rotor-stator interface, allowing the motor to spin in the CW direction [11],[12]. The switching probability is also affected by motor torque, suggesting that the switch complex senses the stator-rotor interaction as well as the concentration of CheY-P [13],[14]. Recently, turnover of FliM and heterogeneity in the number of FliM subunits within functioning motors have been reported [15],[16]. The turnover rate is increased by the presence of CheY-P, implying that turnover of FliM may be directly involved in the switching process [15].

FliG forms a ring on the cytoplasmic face of the MS ring with 26-fold rotational symmetry [17],[18]. FliG consists of three domains, FliGN, FliGM, and FliGC. FliGN is responsible for association with the cytoplasmic face of the MS ring [17],[19], and FliGM and FliGC are required for an interaction with FliM [20]. The FliGM domains of adjacent subunits are fairly close to each other in the FliG ring [21]. The crystal structure of FliGMC of Thermotaoga martima (Tm-FliGMC) shows that FliGM and FliGC are connected by an extended α-helical linker (helix E) [22]. The linker contains two well-conserved Gly residues and hence might be flexible [22]. This finding is supported by genetic analyses of FliG and a computer-generated prediction of its secondary structure [23],[24]. Critical charged residues, which are responsible for an interaction with MotA [4]–[6], are clustered together along a prominent ridge on FliGC [25]. It has been shown that the elementary process of torque generation by the stator-rotor interaction is symmetric in CCW and CW rotation [26], although the torque-speed curves are distinct between them [27].

A recent report on the full-length FliG structure of Aquifex aeolicus has shown two distinct conformational differences between the full-length FliG and FliGMC structures [28]. The helix E linker is held in a closed conformation by packing tightly against an α-helix (helix n), which connects FliGN to FliGM in a way similar as helix E connects FliGM and FliGC in the full-length FliG structure. Helix E is dissociated from FliGM in the Tm-FliGMC structure, resulting in its being in an open conformation. The conformation of FliGC is also different in these two structures. Combined with the previous genetic data, it has been proposed that the closed conformation represents FliG during CCW rotation and that switching to CW rotation may be accompanied by the dissociation of helix E from FliGM to form an open conformation.

The S. enterica FliG(ΔPAA) mutant protein has three-amino-acid deletion at positions 169 to 171. Motors containing this protein are extremely CW biased [29]. The mutant motors remain in CW rotation even in the presence of a cheY deletion, indicating that the motor is locked in the CW state [29]. Therefore, it is likely that binding of CheY-P to FliM may introduce a conformational change in FliG similar to the one introduced by the in-frame PAA deletion. To elucidate the switching mechanism, we crystallized a fragment of a T. maritima FliG mutant variant, FliGMC(ΔPEV), which contains a deletion equivalent to S. enterica FliGMC(ΔPAA), and determined its structure at 2.3 Å resolution. Based on the structural difference among full-length A. aeolicus FliG, wild-type Tm-FliGMC, and its deletion variant, we suggest that a reorientation of helix E relative to FliGM is important for switching and propose a new model for the arrangement of FliG subunits in the motor.

Results

Characterization of S. enterica fliG(ΔPAA) Mutant

The motors of the fliG(ΔPAA) mutant rotated only CW (Figure S1A), whereas wild-type motors rotated exclusively CCW under our experimental conditions. The motors of the deletion mutant produced normal torque under a wide range of external-load conditions, indicating that the deletion does not affect the torque generation step (Figure S1B). Introduction of a cheA-Z deletion, which causes wild-type motors to spin exclusively CCW [30], into the fliG(ΔPAA) mutant did not change the CW-locked behavior. These results are in good agreement with a previous report [29].

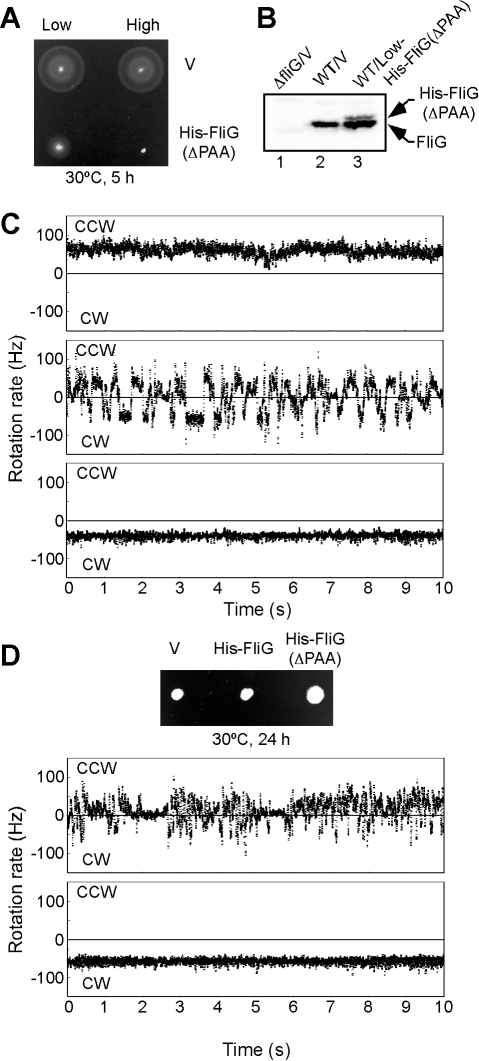

Switching between the CW and CCW states is highly cooperative [31]–[34]. The switching mechanism can be explained by a conformational spread model, in which a switching event is mediated by conformational changes in a ring of subunits that spread from subunit to subunit via nearest-neighbor interactions [34],[35]. Therefore we investigated rotation of a single motor composed of wild-type and mutant FliG subunits at different ratios. FliG(ΔPAA) inhibited expansion of wild-type colonies in semi-solid agar (Figure 1A), even when its expression level was ca. 5-fold lower than the level of wild-type FliG expressed from the chromosome (Figure 1B). Bead assays revealed that the decrease in colony expansion results from an increase in both switching frequency and prolonged pausing (Figure 1C). In addition, a low level expression of FliG(ΔPAA) partially increased the colony expansion of the ΔcheA-Z smooth-swimming mutant, presumably because switching now occurred (Figure 1D, upper and middle panels). These results suggest that even a small fraction of FliG(ΔPAA) in a motor can affect the CW-CCW switching.

Figure 1. Dominant-negative effect of FliG(ΔPAA) on motility of wild-type cells.

(A) Motility of SJW1103 cells (wild-type) transformed with pET19b (indicated as Low-V), pTrc99A (indicated as High-V), pGMK4000 (pET19b/His-FliG(ΔPAA), indicated as Low-FliG(ΔPAA)), and pGMM4500 (pTrc99A/His-FliG(ΔPAA), indicated as High-FliG(ΔPAA)) in semi-solid agar plates. (B) Expression levels of FliG and His-FliG(ΔPAA). Immunoblotting, using polyclonal anti-FliG antibody, of whole cell proteins. Lane 1, MKM1/pET19b (indicated as ΔfliG/V); lane 2, SJW1103/pET19b (indicated as WT/V); lane 3, SJW1103/pGMK4000 (indicated as WT/Low-His-FliG(ΔPAA)). Arrows indicate positions of FliG and His-FliG(ΔPAA). (C) Measurement of CCW and CW rotation of the flagellar motor by bead assays. We used SJW46 (fliC(Δ204–292)) as a host because it produces flagellar motors with the sticky flagellar filaments, which are easily labeled with polystyrene beads. CCW, counterclockwise rotation; CW, clockwise rotation. Upper panel: SJW46 carrying pET19b. Middle panel: SJW46 carrying pGMK4000. Bottom panel: SJW46 carrying pGMM4500. (D) Effect of FliG(ΔPAA) on motility of a ΔcheA-Z mutant. Upper panel: Motility of SJW3076 (ΔcheA-Z) transformed with pET19b, pGMK3000 (pET19b/His-FliG), or pGMK4000 in semi-solid agar. Middle panel: measurement of CCW and CW rotation of the flagellar motor of MM3076iC/pGMK4000. Bottom panel: measurement of CCW and CW rotation of the flagellar motor of MM3076iC/pGMM4500.

The CW-CCW transition, which is very fast in wild-type motors, became significantly longer in mixed motors (Figure 1), suggesting that, as proposed previously [24], the motor can exist in multiple states. A much higher expression of FliG(ΔPAA) completely inhibited wild-type motility (Figure 1D) and did not increase the colony size of the ΔcheA-Z mutant in semi-solid agar plates because of the extreme CW-biased rotation of its flagella (Figure 1C and D, lower panel), in agreement with data showing that a higher expression level of wild-type FliG is required for complementation of the fliG(ΔPAA) mutant (Figure S2). Therefore, we conclude that wild-type FliG is more stable in the CCW state than in the CW state, whereas FliG(ΔPAA) is more stable in the CW state than in the CCW state.

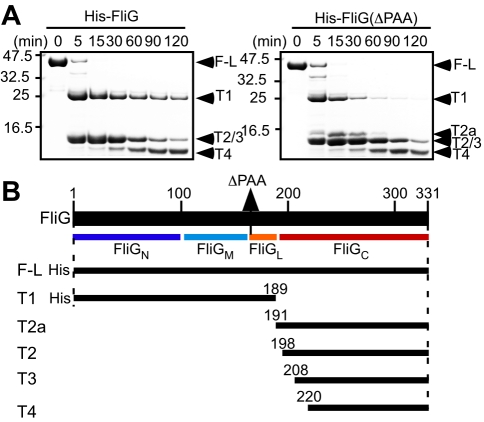

Limited Proteolysis of FliG and FliG(ΔPAA)

To identify structural differences between the CW and CCW states of FliG, we carried out limited trypsin proteolysis of the wild-type and mutant FliG proteins and analyzed the products by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry and N-terminal amino-acid sequencing (Figure 2). Both the wild-type and mutant FliG proteins were cleaved between helix E and FliGC, producing the T1 and T2a fragments. This indicates that there is a flexible region between them. The T1 fragment derived from FliG(ΔPAA) was less stable than the T1 fragment from wild-type FliG, suggesting that the deletion causes a conformational change in FliGM and helix E. In contrast, the T2a fragment was more stable in FliG(ΔPAA) than in the wild-type. The T2a fragment derived from the wild-type FliG protein was detected by MALDI-TOF but not on SDS-PAGE gels, indicating that the wild-type T2a fragment is rapidly converted into the T2 fragment. These results suggest that the deletion also influences the conformation in the region between helix E and FliGC.

Figure 2. Conformation of FliG in solution.

(A) Protease sensitivity of His-FliG (left panel) and His-FliG(ΔPAA) (right panel). Arrowheads indicate intact molecule and proteolytic products on SDS-PAGE gels with labels corresponding to those in the diagram shown in (B). (B) Proteolytic fragments identified by MALDI-TOF mass spectroscopy and N-terminal amino acid sequencing.

Structural Comparison of Tm-FliGMC and Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV)

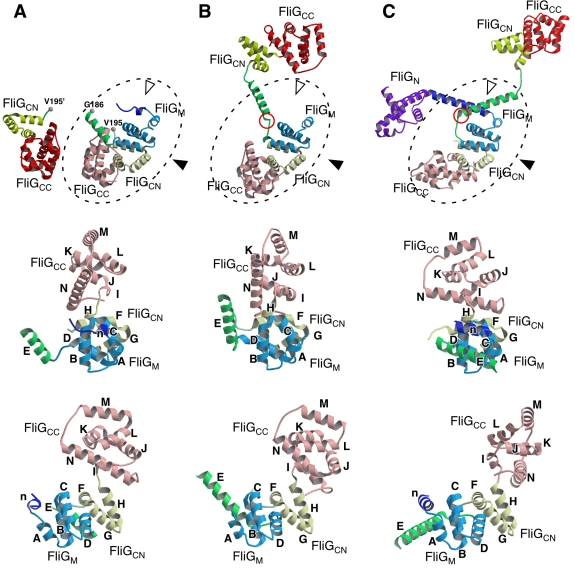

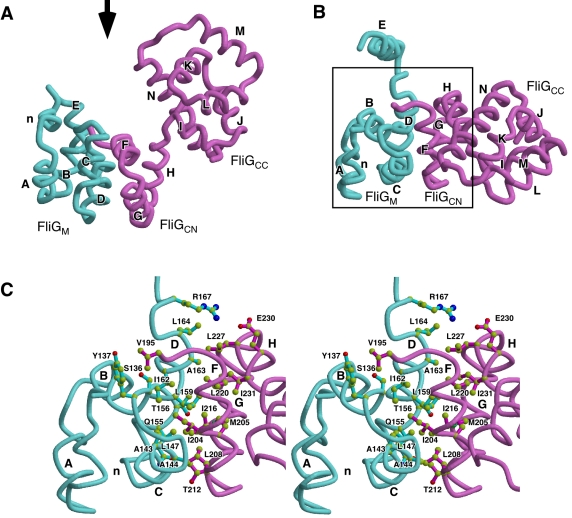

We tried crystallizing both wild-type FliG and FliG(ΔPAA) from S. enterica but did not succeed in obtaining crystals. It has been reported that the crystal structure of a fragment (residues 104–335) of T. martima FliG (Tm-FliGMC) consists of FliGM, FliGC, and helix E connecting the two domains ([22]; PDB ID, 1lkv). FliGC can be further divided into two sub-domains (FliGCN and FliGCC). Therefore, we introduced the deletion (ΔPEV), equivalent to ΔPAA, into Tm-FliGMC (Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV)) and determined its structure at 2.3 Å resolution by X-ray crystallography (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Comparison of the structures of Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV), Tm-FliGMC, and Aa-FliG.

Cα ribbon representation of (A) Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV), (B) Tm-FliGMC (PDB code 1lkv), and (C) Aa-FliG (PDB code 3hjl), color coded from purple to red going from the N- to the C-terminus. The FliGM-FliGC unit with helix E is surrounded by broken line in the upper panels. The white and black arrowheads in the upper panels represent view directions of the middle and the lower panels, respectively. (A, upper panel) Two possible connections between the M-domain and the C-domain (FliGCN and FliGCC) in the Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV) crystal are shown. Because the residues between G186 and V195 are invisible in the density map, G186 can be to either V195 or V195'. The two possible C-domains are indicated by vivid and dull colors. (B, C, upper panel) The orientation of the Tm-FliGMC and Aa-FliG molecule is adjusted to that of Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV) by the M-domain (colored cyan). FliGCN and FliGCC of an adjacent molecule related by crystallographic symmetry are shown by dull yellow and dull pink, respectively. The middle panels show comparison of the FliGM-FliGC unit structures. All the elements of secondary structure are labeled in alphabetical order from the N- to the C-terminus, except for “n,” which is not found in the Tm-FliGMC structure. The lower panels are viewed from the right of the middle panels.

FliGM, FliGCN, and FliGCC are composed of five (n, A–D), three (F–H), and six (I–N) helices, respectively (Figure 3). Since the residues between G186 and V195 are invisible in the crystal, there are two possible ways to connect FliGM with FliGCN: one is to connect FliGM with its adjacent FliGCN (G186 to V195 in Figure 3A upper panel and Figure S3A), and the other is with a distant FliGCN (G186 to V195' in Figure 3A upper panel and Figure S3A). The Cα distance between G186 and V195, and G186 and V195' is 16.9 Å and 27.9 Å, respectively. Therefore, to connect with the distant FliGCN, the invisible chain would have a fully extended conformation. We thus conclude that the connection with the adjacent FliGCN is more plausible.

Compared with the structure of wild-type Tm-FliGMC, FliG(ΔPEV) showed a significant conformational change in the hinge between helix E and FliGM, leading to a very different orientation of helix E relative to FliGM (Figure 3A and B, and Figure 4A and C). As a result, some of the residues in FliGM are exposed to solvent in the Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV) structure. This result is in good agreement with the data obtained by limited proteolysis (Figure 2). Thus, the conformational difference in the FliGM-helix E hinge between the wild-type and mutant structures may represent the conformational switch between the CW and CCW states of the motor.

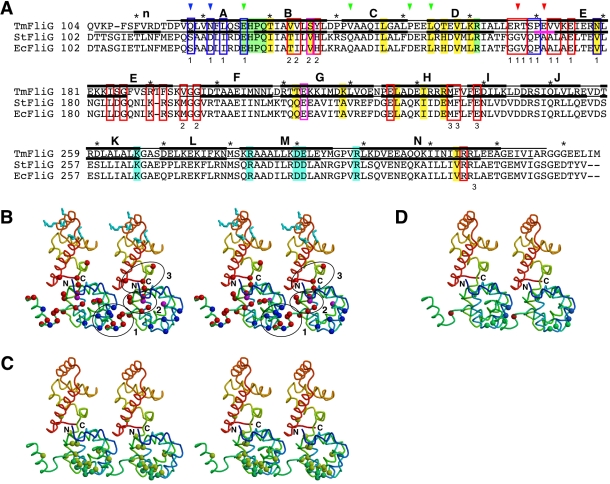

Figure 4. Structural comparison of the FliGM-FliGC unit.

(A) Comparison of Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV) and wild-type Tm-FliGMC (PDB code 1lkv). A FliGM-FliGC unit of wild-type Tm-FliGMC, which is composed of FliGM of one subunit and FliGC of the neighboring subunit related by 2-fold crystallographic symmetry, is superimposed onto Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV) using Cα atoms of V117-L165 and G196-F236 for least-square fitting. FliGM with helix E and FliGC of Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV) are colored cyan and blue, respectively. FliGM with helix E and FliGC of wild-type Tm-FliGMC are yellow and orange, respectively. (B) Comparison of Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV) with Aa-FliG (PDB code 3hjl). A FliGM-FliGC unit of Aa-FliG, which is composed of FliGM of one molecule and FliGC of the neighboring molecule related by 2-fold crystallographic symmetry, is superimposed onto Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV) using Cα atoms of the same region used in (A). Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV) is shown in the same color as in (A), and FliGM and FliGC of Aa-FliGMC are shown in green and red, respectively. (C) Comparison of the orientation of helix E. The FliGM-FliGCN units of wild-type Tm-FliGMC and wild-type Aa-FliGMC are superimposed on Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV). The models are shown in the same colors used in (A) and (B).

The C-terminal half of helix E is disordered and protrudes into the solvent channel in the Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV) crystal (Figure S3A). In contrast, helix E in the wild-type crystal is stabilized by forming an anti-parallel four-helix bundle structure with the E helices of three adjacent subunits related by crystallographic symmetry (Figure S3B) [22]. Therefore, the orientation of FliGC relative to FliGM is different between the wild-type and the deletion variants (Figure 3A and B upper panel). Because the disordered region of helix E is far from the PEV deletion, we conclude that helix E has a highly flexible nature, which may be responsible for the switching mechanism, as suggested before [23],[24].

Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV) also showed a conformational difference in the H–I loop, resulting in a rigid body movement of FliGCC relative to FliGCN (Figure 3A and B middle and lower panels, and Figure 4A). This movement is consistent with the limited proteolysis data because, in the Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV) structure, FliGCC almost covers D199, which is the residue corresponding to R198 in S. enterica FliG. It is, however, unclear how the deletion affects the conformation of the H–I loop, because neither direct contact between FliGCC and helix E nor significant structural difference in FliGCN is observed.

Comparison of the Structure of Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV) with A. aeolicus FliG

The crystal structure of full-length A. aeolicus FliG (Aa-FliG) showed that the conformation of helix E and the orientation of FliGCN relative to FliGCC are quite distinct from those of wild-type Tm-FliGMC [28]. We compared the Aa-FliG structure with the Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV) structure and found that the conformation of helix E and the relative conformation of FliGCC to FliGCN are also different in those two structures (Figure 3A and C, and Figure 4B and C). The conformational differences are greater than those between Tm- FliGMC and Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV). The conformation of helix E in Aa-FliG seems to be stabilized by interactions of helix E with FliGM and helix n in the crystal (Figure S3C). As mentioned earlier, the conformation of helix E and the orientation of FliGCC to FliGCN are also different between the wild-type and mutant Tm-FliGMC structures. Therefore, these conformational differences among the three structures strongly suggest that both helix E and the linker connecting FliGCN to FliGCC are highly flexible.

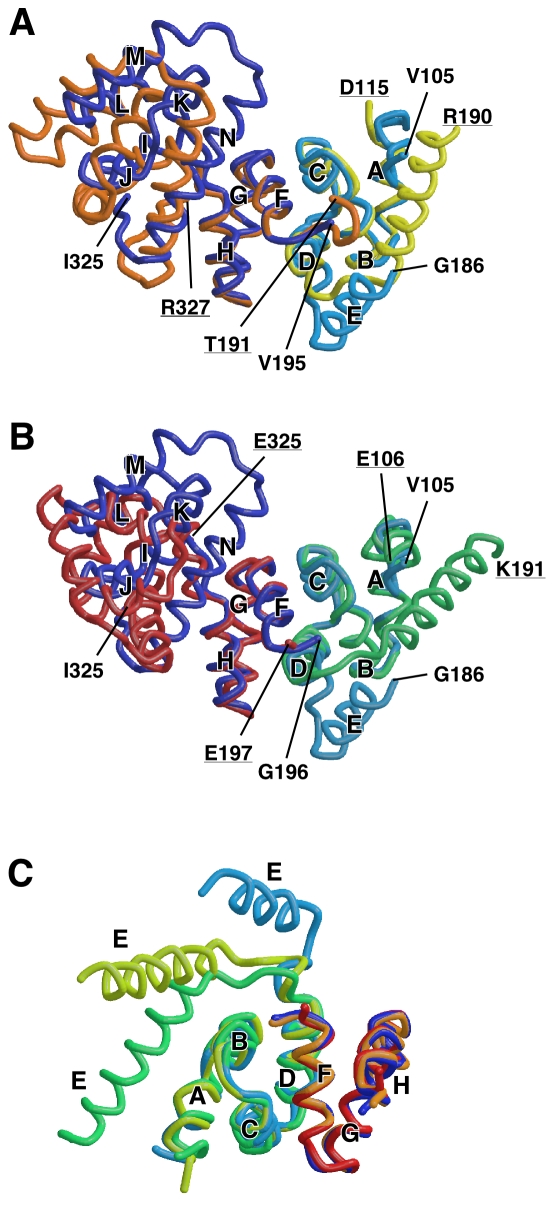

Interaction between FliGM and FliGCN

The interaction between FliGM and FliGCN, which share the armadillo repeat motif [36] that is often responsible for protein-protein interaction, is very tight in the Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV) crystal, in agreement with a previous report [28]. FliGM and FliGCN can be identified as a single domain, although it is unclear whether the two domains belong to the same molecule or not because the residues between Gly-186 and Val-195 are invisible in the crystal (Figures 3A and S3A). The interaction surface between FliGM and FliGCN is formed by the C-terminal portion of αB, αC, and αD of FliGM, and αF, αG, and the N-terminal portion of αH of FliGCN, respectively (Figure 5A and B). The interface is highly hydrophobic. Ala-143, Ala-144, Leu-147, Leu-156, Leu-159, Ile-162, and Ala163 of FliGM, and Ile-204, Met-205, Leu-208, Ile-216, Leu-220, Leu-227, and Ile-231 of FliGCN are mainly involved in the tight domain interaction. Leu-159 is located at the center of the hydrophobic interface (Figure 5C). Around the hydrophobic core, hydrophilic interactions between Arg-167 and Glu-230, and Gln-155 and Thr-212, also contribute to the domain interaction (Figure 5C). These interactions are also conserved in the wild-type Tm-FliGMC and Aa-FliG crystals, in which FliGM interacts with FliGCN of an adjacent molecule related by crystallographic symmetry (Figures 3 and S3B). The FliGM-FliGCN unit in the wild-type Tm-FliGMC structure can be superimposed onto that in Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV) with root mean square deviation of 0.46 Å for corresponding Cα atoms (Figure 4A and C), and that in Aa-FliG with 0.79 Å (Figure 4B and C). These observations support the idea that the FliGM-FliGCN unit is a functionally relevant structure [28]. This is in good agreement with the previous mutational study showing that most of the known point mutations that affect FliM-binding [37] are located either on the bottom surface of the FliGM-FliGCN unit or on the interaction surface between FliGM and FliGCN (Figure 6A and C).

Figure 5. Domain interface between FliGM and FliGC.

The two domains are colored cyan and magenta, respectively. (A) Structure of Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV). The secondary structure elements are labeled as in Figure 3. (B) Structure of Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV) viewed from the direction of arrow in (A). (C) Stereo view of the domain interface between FliGM and FliGCN. The boxed area in (B) is shown. Side chains of the residues contributing strongly to the interaction are shown in a ball-and-stick representation, with carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen atoms indicated by yellow, blue, and red balls, respectively. Bonds are shown with colors of the domains to which they belong.

Figure 6. A plausible model for arrangement of FliG subunits in the rotor.

(A) A primary sequence alignment of FliGMC from T. maritima (TmFliG), Salmonella Typhimurium (StFliG), and Escherichia coli (EcFliG). The regions involved in the structure models of Tm-FliGMC and Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV) are shown in black bars above and below the Tm-FliG sequence, respectively. The α-helical regions are indicated by thick bars labeled with the same codes used in Figure 3. The region of the three-amino-acid deletion is shown by the magenta bar. The charged residues essential for the motor function are highlighted in cyan. The EHPQR motif is highlighted in green, and the other residues thought to be related to FliM-binding are shaded highlighted in yellow [21],[37]. In vivo cross-linking experiments using various Cys-substitution mutants of FliGM have shown that residues indicated by blue arrows are located near the residues indicated by red ones. The Cys-substitution sites that did not show any cross-linked products are indicated by green arrows [22]. Blue and red boxes indicate point mutations that bias the motor rotation to CCW and CW, respectively [38]. The residues within magenta boxes can give rise to CCW or CW-biased mutants, depending on the substitutions. The numbers under the boxes represent the number of the cluster to which the indicated residues belong. (B–D) Mapping of various mutation sites identified in previous studies on the model of Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV). A stereo pair of the Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV) subunits, color coded from blue to red going from the N- to the C-terminus, is shown in each panel. (B–C) Stereo diagram of the subunit arrangement model. (B) The charged residues essential for motor function are shown in stick representation colored in cyan. Residues at which substitutions affect the direction of motor rotation are indicated by balls: blue, CCW motor bias; red, CW motor bias; magenta, CCW or CW motor bias, depending on the substitution. The clusters of residues targeted by mutations are surrounded by ellipsoids and labeled (1, 2, and 3). (C) Residues involved in FliM binding are indicated by balls: yellow, residues at which substitutions decrease FliM binding; green, the EHPQR motif. (D) Residues substituted with Cys for in vivo cross-linking experiments are shown by balls. Residues indicated in blue cross-linked to residues indicated in red. Residues that produced no cross-linking products are colored in green.

Discussion

The default direction of the wild-type flagellar motor of Salmonella enterica is CCW, and the binding of CheY-P to FliM and FliN increases the probability of CW rotation. CheY-P binding induces conformational changes in FliM and FliN that are presumably transmitted to FliG, which directly interacts with MotA to produce torque [1],[2]. Mutations located in and around helix E FliG, which connects the FliGM and FliGC domains, generate a diversity of phenotype, including motors that are strongly CW biased, infrequent switchers, rapid switchers, and transiently or permanently paused, suggesting that helix E is directly involved in the switching of the flagellar motor [24]. However, it remains unclear how helix E affects the switch.

To investigate the switching mechanism, we characterized an extreme CW-biased S. enterica mutant in which an in-frame deletion of three residues, Pro-169, Ala-170, and Ala-171, in FliG caused an extreme CW-biased rotation even in the absence of CheY. Motors containing the FliG(ΔPAA) protein showed normal torque generation under a wide range of external-load conditions (Figure 1 and Figure 1S). Thus, the conformational change in FliG induced by ΔPAA is presumably similar to one induced by CheY-P binding to FliM and FliN. Limited proteolysis revealed that ΔPAA induces conformational changes in the hinge between FliGM and helix E (Figure 2). This result is in agreement with the crystal structure of Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV), which shows that the orientation of helix E relative to FliGM has changed significantly compared to wild-type FliG (Figure 3).

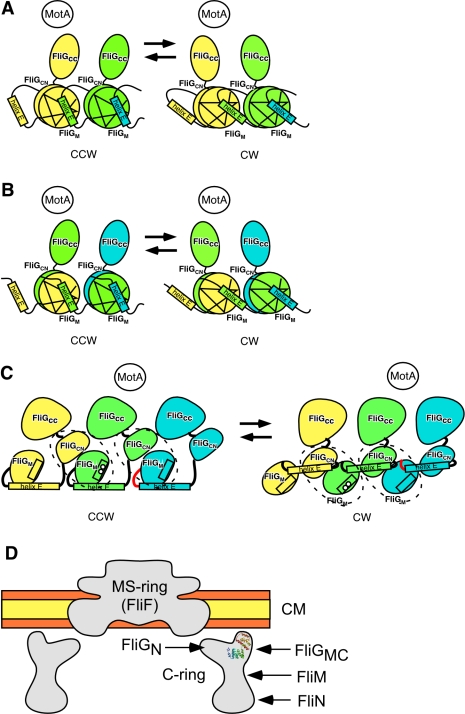

FliG forms a ring on the cytoplasmic face of the MS ring [17],[18]. In vivo disulfide cross-linking experiments using Cys-substituted FliG proteins have suggested that helix A is close to the D–E loop of the adjacent FliG molecule in the FliG ring [21]. Both a conserved EHPQR motif in FliGM and a conserved surface-exposed hydrophobic patch of FliGCN are important for the interactions with FliM [21]. Because the conserved charged residues on helix M in FliGCC are responsible for its interaction with MotA [4],[5],[25], which is embedded in the cytoplasmic membrane, helix M must lie on top of FliGCC [21],[28]. Considering those facts in light of the crystal structure of Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV) described here, we propose a new model for arrangement of FliG subunits in the motor (Figures 6 and 7).

Figure 7. Possible models for cooperative switching.

(A) The most plausible model. Two adjacent FliG molecules are colored yellow and green. The conformational change of the hinge between FliGM and helix E not only changes the orientation within its own subunit but also influences the orientation of the neighboring subunit through the interaction between helix E and FliGM of the neighbor. (B) Another possible model. Helix E in one subunit is linked to FliGCN in the adjacent subunit. Therefore, a single functional unit consists of FliGM and helix E of one molecule and FliGCN and FliGCC of the other molecule. Three adjacent FliG molecules are colored yellow, green, and cyan. FliGM of the cyan molecule, and FliGCN and FliGCC of the yellow molecule are not shown. (C) The cooperative switching model proposed by Lee et al. Three FliG molecules are colored by yellow, green, and cyan. The FliGM-FliGC units are surrounded by broken lines. The closed conformation (left panel, helix E interacts with FliGCN) changes to the open conformation (right panel, helix E dissociates from FliGCN), inducing the rotation of the FliGM-FliGC unit and additional rotation of FliGCN. The box in the FliGM indicates helix A. The open circles represent the sites linked to the D–E loop (colored red) by in vivo disulfide cross-linking. (D) Possible orientation of the FliGM-FliGC unit in the rotor. The hydrophilic surface and the hydrophobic core layers of the cytoplasmic membrane are shown in orange and yellow, respectively.

In the proposed model, the conserved charged residues on helix M are located on the top of the FliGM-FliGC unit and the EHPQR motif is present at the bottom of the unit (Figure 6B and C). The conserved hydrophobic patch, and most of the point mutation sites involved in the interaction with FliM, is localized at the bottom of the FliGMFliGCN units around the EHPQR motif or on the interface between the FliGM and FliGCN. The D–E loop and helix E interact with the FliGM domain in the neighboring subunit, in agreement with data of in vivo cross-linking experiments, which show that residues 117 and 120 (118 and 121 in T. martima) on helix A of one subunit lie close to residues 166 and170 (167 and 171 in T. martima) on the D–E loop of the neighboring subunit [21]. In fact, these residues are very close to each other in our model in positions in which disulfide-crosslinking should occur. Moreover, the position of Cys residues that do not participate in disulfide cross-linking are far from each other in the model (Figure 6D).

Our model can also explain the results of mutational studies of CW and CCW-biased fliG mutants [37],[38]. The mutation sites are widely distributed from helix A to the H–I loop. Most of them are localized in three regions in our model (Figure 6A and B). In the first region, the CCW-biased mutations, which are located on helix A, affect residues close to residues targeted by CW-biased mutations, which are on a segment between helix D and E of the adjacent subunit (Figure 6A and B, 1). Because these residues are distributed on the interaction surface between the neighboring subunits, they presumably affect cooperative changes in subunit conformation. A second cluster of residues targeted by CW-biased mutations is located on the C-terminal half of helix B and the E–F loop (Figure 6A and B, 2). These mutations may change the orientation of the E–F loop and probably alter the orientation of helix E, resulting in unusual switching behavior. The third cluster of residues affected by mutations causing a CW switching bias is located near the loop between helices H and I (Figure 6A and B, 3). This region determines the relative orientation of FliGCC to the FliGM-FliGCN unit, and therefore the mutations may change the orientation of FliGCC to cause anomalous switching behavior.

Helix E is directly involved in the switching mechanism, but how does the structure of helix E affect the orientation of the FliGM-FliGC unit? Since the D–E loop and helix E interact with FliGM in the neighboring subunit, we propose that a hinge motion of helix E may directly change the orientation of the neighboring FliGM domain (Figure 7A). This mechanism could explain the cooperative switching of the motor. The conformational changes of FliM induced by association or dissociation of CheY-P may trigger conformational changes in the FliGM-FliGC unit that it contacts, leading to a large change in the interaction between FliGCC and MotA. The conformational change in one unit is probably accompanied by a conformational change in the loop between FliGM and helix E. This change could influence the orientation of the neighboring subunit through the interaction between helix E and FliGM of the neighbor, thereby propagating the conformational change to the neighboring subunit (Figure 7A).

If helix E actually contacts the more-distant FliGCN in the crystal structure, an alternative interaction could be responsible for the cooperative switching (Figure 7B). However, the same general mechanism involving changes in the conformation of helix E would still be responsible for the cooperative switching.

Recently, Lee et al. have proposed a model for FliG arrangement and switching based on the structural differences in Aa-FliG and Tm-FliGMC [28]. In the crystal structure of Aa-FliG, the hydrophobic patch in FliGM is covered by the N-terminal hydrophobic residues of helix E (closed conformation), whereas the patch is exposed in Tm-FliGMC (open conformation). Because mutations that may disturb the hydrophobic interaction result in strong CW-bias in motor rotation [38], the structures of Aa-FliG and Tm-FliGMC are proposed to be in the CCW and CW states, respectively [28]. The hydrophobic patch is also exposed in the Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV) structure, although the conformation of helix E is different from that of Tm-FliGMC. Since ΔPAA in S. enterica FliG (ΔPEV in T. maritima) caused an extreme CW-bias, it is possible that the dissociation of helix E from FliGM leads to CW rotation. In our model, however, the hydrophobic patch of the FliGM is covered by the hydrophobic residues in the C-terminal half of helix E of the adjacent subunit. This arrangement raises the possibility that the closed conformation of helix E found in the Aa-FliG structure is an artifact of crystal packing.

Lee et al. assume that the FliGM-FliGC unit is present in the rotor ring, and hence is in agreement with the results of most of mutational studies. However, the arrangement of the subunits and the mechanism of switching are different than in our model. In their model, dynamic motion of helix E and helix n induces a large conformational change of the FliGM-FliGC unit, including the rotation of FliGM-FliGCN unit and relative to the FliGCC to the unit, leading to a change in the arrangement of the charged residues on helix M (Figure 7C) [28]. Cooperative switching is explained by the strong interaction between FliGCN of one subunit and FliGCC of the adjacent subunit. However, helix A of one subunit and the D–E loop of the adjacent subunit are always at a considerable distance in both the CW and CCW states. Hence, their model cannot explain the in vivo disulfide cross-linking experiments (Figure 7C) [21]. Since our new model can explain the cross-linking data, it appears to be more plausible than the model proposed by Lee et al. [28].

Although our model is consistent with most of the previous experimental data, it still contains ambiguity. The available density map of the basal body obtained by electron cryo-microscopy is not high enough to allow fitting of the atomic model. Thus, a higher-resolution rotor-ring structure will be required to build a more precise model to explain the molecular mechanism of directional switching.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Media

S. enterica strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. L-broth, soft agar plates, and motility media were prepared as described [39],[40]. Ampicillin was added to a final concentration of 100 µg/ml.

Table 1. Strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strains and Plasmids | Relevant Characteristics | Source or Reference |

| Salmonella | ||

| SJW1103 | Wild type for motility and chemotaxis | [48] |

| SJW46 | fliC(Δ204–292) | [49] |

| SJW2811 | fliG(ΔPAA) | [10] |

| SJW3076 | Δ(cheA–cheZ) | [30] |

| MKM1 | ΔfliG | [19] |

| MM3076iC | Δ(cheA–cheZ), fliC (Δ204–292) | [50] |

| MMG1001 | ΔfliG fliC(Δ204–292) | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pET19b | Expression vector | Novagen |

| pTrc99A | Expression vector | Pharmacia |

| pGKM3000 | pET19b/His-FliG | [19] |

| pGKM4000 | pET19b/His-FliG(ΔPAA) | This study |

| pGMM3500 | pTrc99A/His-FliG | This study |

| pGMM4500 | pTrc99A/His-FliG(ΔPAA) | This study |

| pGMM5000 | pET22b/Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV) | This study |

Motility Assay

Fresh colonies were inoculated on soft tryptone agar plates and incubated at 30°C.

Bead Assay for Motor Rotation

Bead assays were carried out using polystyrene beads with diameters of 0.8, 1.0, and 1.5 mm (Invitrogen), as described before [8]. Torque calculation was carried out as described [8].

Preparation of Whole Cell Proteins and Immunoblotting

Cultures of S. enterica cells grown at 30°C were centrifuged to obtain cell pellets. The cell pellets were resuspended in SDS-loading buffer, normalized in cell density to give a constant amount of cells. Immunoblotting with polyclonal anti-FliG antibody was carried out as described [41].

Purification of His-FliG and His-FliG(ΔPAA) and Limited Proteolysis

His-FliG and His-FliG(ΔPAA) were purified by Ni-NTA affinity chromatography as described before [39]. His-FliG and its mutant variant (0.5 mg/ml) were incubated with trypsin (Roche Diagnostics) at a protein to protease ratio of 300∶1 (w/w) in 50 mM K2HPO4-NaH2PO4 pH 7.4 at room temperature. Aliquots were collected at 0, 5, 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min and trichloroacetic acid was added to a final concentration of 10%. Molecular mass of proteolytic cleavage products was analyzed by a mass spectrometer (Voyager DE/PRO, Applied Biosystems) as described [42]. N-terminal amino acid sequence was done as described before [42].

Purification, Crystallization, Data Collection, and Structure Determination of Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV)

Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV) was purified as described previously [23]. Crystals of Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV) were grown at 4°C using the hanging-drop vapor-diffusion method by mixing 1 µl of protein solution with 1 µl of reservoir solution containing 0.1 M sodium phosphate-citrate buffer pH 4.2–4.4, 36%–50% PEG200, and 200 mM NaCl. Initially, we tried to solve the structure by the molecular replacement method using Tm-FliGMC structure (PDB ID: 1 lkv) as a search model. However, no significant solution was obtained, even though individual domains were used as search models. Therefore, we prepared heavy-atom derivative crystals and determined the structure using the anomalous diffraction data from the derivatives.

Derivative crystals were prepared by soaking in a reservoir solution containing K2OsCl6 at 50% (v/v) saturation for one day. Crystals of Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV) and its Os derivatives were soaked in a solution containing 90%(v/v) of the reservoir solution and 10%(v/v) 2-Methyl-2,4-pentanediol for a few seconds, then immediately transferred into liquid nitrogen for freezing. All the X-ray diffraction data were collected at 100 K under nitrogen gas flow at the synchrotron beamline BL41XU of SPring-8 (Harima, Japan), with the approval of the Japan Synchrotron Radiation Research Institute (JASRI) (Proposal No. 2007B2049). The data were processed with MOSFLM [43] and scaled with SCALA [44]. Phase calculation was performed with SOLVE [45] using the anomalous diffraction data from Os-derivative crystals. The best electron-density map was obtained from MAD phases followed by density modification with DM [44]. The model was constructed with Coot [46] and was refined against the native crystal data to 2.3 Å using the program CNS [47]. About 5% of the data were excluded from the data for the R-free calculation. During the refinement process, iterative manual modifications were performed using “omit map.” Data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in Tables S1 and S2, respectively.

Supporting Information

Effects of the in-frame deletion of residues PAA of S. enterica FliG on the direction of flagellar motor rotation and torque generation. (A) Measurement of CCW and CW rotation of the flagellar motor. Rotation individual flagellar motors of SJW46 transformed with pGMK3000 (pET19b/His-FliG, indicated as WT) (left) or pGMK3000 (pET19b/His-FliG(ΔPAA), indicated as FliG(ΔPAA)) (right) were carried out by tracking the position of 1.0 µm bead attached to the sticky flagellar filament. Measurements were made at ca. 23°C. CCW, counterclockwise rotation; CW, clockwise rotation. (B) Measurements of the rotational speeds of single flagellar motors labeled with 0.8 µm (right), 1.0 µm (left), and 1.5 µm (middle) beads.

(0.06 MB TIF)

Motility assays for complementation of the motility of a ΔfliG null mutant (left) and a fliG(ΔPAA) mutant transformed with pET19b (indicated as Low-V), pTrc99A (indicated as High-V), pGMK4000 (pET19b/His-FliG(ΔPAA), indicated as Low-FliG(ΔPAA)), and pGMM4500 (pTrc99A/His-His-FliG(ΔPAA), indicated as High-FliG(ΔPAA)) in semi-solid agar. The plates were incubated at 30°C for the length of time indicated.

(0.31 MB TIF)

Molecular packing in the crystal. (A) Stereo view of the molecular packing of Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV) in the P62 crystal, projected down the c axis. Molecules are indicated by Cα backbone traces. A pair of FliG molecules related by two-fold crystallographic symmetry is highlighted in cyan and yellow for FliGM and FliGC, respectively. Other molecules are shown in grey. G186 and V195 are indicated by blue and magenta balls, respectively. G186 can be connected to V195 (solid line) or V195' (dashed line). (B) Stereo view of four symmetry-related molecules of Tm-FliGMC that form the inter-molecular four-helix bundle structure in the P6422 crystal (PDB code: 1lkv). FliGM and FliGCN of the subunit colored by cyan form the FliGM-FliGCN units with FliGCN and FliGM of the subunit colored by yellow, respectively, and FliGM and FliGCN of the subunit colored by green form the FliGM-FliGCN units with FliGCN and FliGM of the subunit colored by orange, respectively. (C) Stereo view of the molecular packing of Aa-FliG in the P21 crystal (PDB code: 3hjl), projected down the c axis. The molecules related by crystallographic 21 symmetry are colored by cyan and yellow. The cyan molecule located in the centre of the panel is labeled, and helix n and helix E of the center molecule are highlighted in orange.

(2.96 MB TIF)

Data collection statistics.

(0.04 MB PDF)

Refinement statistics.

(0.03 MB PDF)

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Kihara for her kind gift of pGMK3000 and pGMK4000, cloning Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV) into a pET19b vector, critical reading of the manuscript, and helpful comments. N. Shimizu, M. Kawamoto, and K. Hasegawa at SPring-8 provided technical help with the use of beam lines. This research was supported in part by the National Science Foundation through TeraGrid resources provided by the National Center for supercomputing Applications; we would like to specifically thank Susan John for assistance with the allocation and technical help. These experiments were originally designed by M. Kihara and the late R. M. Macnab, who passed away suddenly on September 7, 2003. This manuscript is duly dedicated to both M. Kihara and the late R. M. Macnab.

Footnotes

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research to K.I. (18074006) and K.N. (16087207 and 21227006). This research was supported in part by the National Science Foundation through TeraGrid resources provided by the National Center for supercomputing Applications under grant number TG-MCB060069N. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Berg H. C. The rotary motor of bacterial flagella. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:19–54. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sowa Y, Berry R. M. Bacterial flagellar motor. Q Rev Biophys. 2008;41:103–132. doi: 10.1017/S0033583508004691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Minamino T, Imada K, Namba K. Molecular motors of the bacterial flagella. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2008;18:693–701. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lloyd S. A, Blair D. F. Charged residues of the rotor protein FliG essential for torque generation in the flagellar motor of Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1997;266:733–744. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou J, Lloyd S. A, Blair D. F. Electrostatic interactions between rotor and stator in the bacterial flagellar motor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:6436–6441. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morimoto Y. V, Nakamura S, Kami-ike N, Namba K, Minamino T. Charged residues in the cytoplasmic loop of MotA are required for stator assembly into the bacterial flagellar motor. Mol Microbiol. 2010;78:1117–1129. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kojima S, Blair D. F. Conformational change in the stator of the bacterial flagellar motor. Biochemistry. 2001;40:13041–13050. doi: 10.1021/bi011263o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Che Y-S, Nakamura S, Kojima S, Kami-ike N, Namba K, Minamino T. Suppressor analysis of the MotB(D33E) mutation to probe the bacterial flagellar motor dynamics coupled with proton translocation. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:6660–6667. doi: 10.1128/JB.00503-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakamura S, Morimoto Y. V, Kami-ike N, Minamino T, Namba K. Role of a conserved prolyl residue (Pro-173) of MotA in the mechanochemical reaction cycle of the proton-driven flagellar motor of Salmonella. J Mol Biol. 2009;393:300–307. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamaguchi S, Aizawa S, Kihara M, Isomura M, Jones C. J, Macnab R. M. Genetic evidence for a switching and energy-transducing complex in the flagellar motor of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1986;166:187–193. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.3.1172-1179.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dyer C. M, Vartanian A. S, Zhou H, Dahlquist F. W. A molecular mechanism of bacterial flagellar motor switching. J Mol Biol. 2009;388:71–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarkar M. K, Paul K, Blair D. Chemotaxis signaling protein CheY binds to the rotor protein FliN to control the direction of flagellar rotation in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:9370–9375. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000935107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fahrner K. A, Ryu W. S, Berg H. C. Bacterial flagellar switching under load. Nature. 2003;423:938. doi: 10.1038/423938a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yuan J, Fahrner K. A, Berg H. C. Switching of the bacterial flagellar motor near zero load. J Mol Biol. 2009;390:394–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delalez N. J, Wadhams G. H, Rosser G, Xue Q, Brown M. T, Dobbie I. M, Berry R. M, Leake M. C, Armitage J. P. Signal-dependent turnover of the bacterial flagellar switch protein FliM. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11347–11351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000284107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fukuoka H, Inoue Y, Terasawa S, Takahashi H, Ishijima A. Exchange of rotor components in functioning bacterial flagellar motor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;394:130–135. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.02.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Francis N. R, Irikura V. M, Yamaguchi S, DeRosier D. J, Macnab R. M. Localization of the Salmonella typhimurium flagellar switch protein FliG to the cytoplasmic M-ring face of the basal body. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:6304–6308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suzuki H, Yonekura K, Namba K. Structure of the rotor of the bacterial flagellar motor revealed by electron cryomicroscopy and single-particle image analysis. J Mol Biol. 2004;337:105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kihara M, Miller G. U, Macnab R. M. Deletion analysis of the flagellar switch protein FliG of Salmonella. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:3022–3028. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.11.3022-3028.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown P. N, Terrazas M, Paul K, Blair D. F. Mutational analysis of the flagellar protein FliG: sites of interaction with FliM and implications for organization of the switch complex. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:305–312. doi: 10.1128/JB.01281-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lowder B. J, Duyvesteyn M. D, Blair D. F. FliG subunit arrangement in the flagellar rotor probed by targeted cross-linking. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:5640–5647. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.16.5640-5647.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown P. N, Hill C. P, Blair D. F. Crystal structure of the middle and C-terminal domains of the flagellar rotor protein FliG. EMBO J. 2002;21:3225–3234. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garza A. G, Biran R, Wohlschlegel J. A, Manson M. D. Mutations in motB suppressible by changes in stator or rotor components of the bacterial flagellar motor. J Mol Biol. 1996;258:270–285. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Way S. M, Millas S. G, Lee A. H, Manson M. D. Rusty, jammed, and well-oiled hinges: mutations affecting the interdomain region of FliG, a rotor element of the Escherichia coli flagellar motor. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:3944–3951. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.10.3173-3181.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lloyd S. A, Whitby F. G, Blair D. F, Hill C. P. Structure of the C-terminal domain of FliG, a component of the rotor in the bacterial flagellar motor. Nature. 1999;400:472–475. doi: 10.1038/22794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakamura S, Kami-ike N, Yokota J. P, Minamino T, Namba K. Evidence for symmetry in the elementary process of bidirectional torque generation by the bacterial flagellar motor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:17616–17620. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007448107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yuan J, Fahrner K. A, Turner L, Berg H. C. Asymmetry in the clockwise and counterclockwise rotation of the bacterial flagellar motor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:12846–12849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007333107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee K. L, Ginsburg M. A, Crovace C, Donohoe M, Stock D. Structure of the troque ring of the flagellar motor and the molecular basis for rotational switching. Nature. 2010;466:996–1000. doi: 10.1038/nature09300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Togashi F, Yamaguchi S, Kihara M, Aizawa S. I, Macnab R. M. An extreme clockwise switch bias mutation in fliG of Salmonella typhimurium and its suppression by slow-motile mutations in motA and motB. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2994–3003. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.9.2994-3003.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Magariyama Y, Yamaguchi S, Aizawa S-I. Genetic and behavioral analysis of flagellar switch mutants of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:4359–4369. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.8.4359-4369.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scharf B. E, Fahrner K. A, Turner L, Berg H. C. Control of direction of flagellar rotation in bacterial chemotaxis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:201–206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cluzel P, Surette M, Leibler S. An ultrasensitive bacterial motor revealed by monitoring signaling proteins in single cells. Science. 2000;287:1652–1655. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5458.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bern A, Eisenbach M. Changing the direction of flagellar rotation in bacteria by modulating the ratio between the rotational states of the switch protein FliM. J Mol Biol. 2001;312:699–709. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bai F, Branch R. W, Nicolau D. V, Jr, Pilizota T, Steel B. C, Maini P. K, Berry R. M. Conformational spread as a mechanism for cooperativity in the bacterial flagellar switch. Science. 2010;327:685–689. doi: 10.1126/science.1182105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duke T. A, Le Novère N, Bray D. Conformational spread in a ring of proteins: a stochastic approach to allostery. J Mol Biol. 2001;308:541–553. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huber A. H, Nelson J. W, Weis W. I. Three-dimensional structure of the armadillo repeat region of β-catenin. Cell. 1997;90:871–882. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80352-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marykwas D. L, Berg H. C. A mutational analysis of the interaction between FliG and FliM, two components of the flagellar motor of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1289–1294. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.5.1289-1294.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Irikura V. M, Kihara M, Yamaguchi S, Sockett H, Macnab R. M. Salmonella typhimurium fliG and fliN mutations causing defects in assembly, rotation, and switching of the flagellar motor. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:802–810. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.3.802-810.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Minamino T, Macnab R. M. Interactions among components of the Salmonella flagellar export apparatus and its substrates. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:1052–1064. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Minamino T, Imae Y, Oosawa F, Kobayashi Y, Oosawa K. Effect of intracellular pH on rotational speed of bacterial flagellar motors. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:1190–1194. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.4.1190-1194.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Minamino T, Macnab R. M. Components of the Salmonella flagellar export apparatus and classification of export substrates. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1388–1394. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.5.1388-1394.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Minamino T, Tame J. R. H, Namba K, Macnab R. M. Proteolytic analysis of the FliH/FliI complex, the ATPase component of the type III flagellar export apparatus of Salmonella. J Mol Biol. 2001;312:1027–1036. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leslie A. G. W. CCP4+ESF-EACMB. Newslett Protein Crystallogr. 1992;26:27–33. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Collaborative Computational Project Number 4. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Terwilliger T. C, Berendzen J. Automated MAD and MIR structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1999;55:849–861. doi: 10.1107/S0907444999000839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brunger A. T, Adams P. D, Clore G. M, DeLano W. L, Gros P, et al. Crystallography & NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamaguchi S, Fujita H, Taira T, Kutsukake K, Homma M, Iino T. Genetic analysis of three additional fla genes in Salmonella typhimurium. J Gen Microbiol. 1984;130:255–265. doi: 10.1099/00221287-130-12-3339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yoshioka K, Aizawa S-I, Yamaguchi S. Flagellar filament structure and cell motility of Salmonella typhimurium mutants lacking part of the outer domain of flagellin. J Bcteriol. 1995;177:1090–1093. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.4.1090-1093.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nakamura S, Kami-ike N, Yokota J. P, Kudo S, Minamino T, Namba K. Effect of intracellular pH on the torque-speed relationship of bacterial proton-driven flagellar motor. J Mol Biol. 2009;386:332–338. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Effects of the in-frame deletion of residues PAA of S. enterica FliG on the direction of flagellar motor rotation and torque generation. (A) Measurement of CCW and CW rotation of the flagellar motor. Rotation individual flagellar motors of SJW46 transformed with pGMK3000 (pET19b/His-FliG, indicated as WT) (left) or pGMK3000 (pET19b/His-FliG(ΔPAA), indicated as FliG(ΔPAA)) (right) were carried out by tracking the position of 1.0 µm bead attached to the sticky flagellar filament. Measurements were made at ca. 23°C. CCW, counterclockwise rotation; CW, clockwise rotation. (B) Measurements of the rotational speeds of single flagellar motors labeled with 0.8 µm (right), 1.0 µm (left), and 1.5 µm (middle) beads.

(0.06 MB TIF)

Motility assays for complementation of the motility of a ΔfliG null mutant (left) and a fliG(ΔPAA) mutant transformed with pET19b (indicated as Low-V), pTrc99A (indicated as High-V), pGMK4000 (pET19b/His-FliG(ΔPAA), indicated as Low-FliG(ΔPAA)), and pGMM4500 (pTrc99A/His-His-FliG(ΔPAA), indicated as High-FliG(ΔPAA)) in semi-solid agar. The plates were incubated at 30°C for the length of time indicated.

(0.31 MB TIF)

Molecular packing in the crystal. (A) Stereo view of the molecular packing of Tm-FliGMC(ΔPEV) in the P62 crystal, projected down the c axis. Molecules are indicated by Cα backbone traces. A pair of FliG molecules related by two-fold crystallographic symmetry is highlighted in cyan and yellow for FliGM and FliGC, respectively. Other molecules are shown in grey. G186 and V195 are indicated by blue and magenta balls, respectively. G186 can be connected to V195 (solid line) or V195' (dashed line). (B) Stereo view of four symmetry-related molecules of Tm-FliGMC that form the inter-molecular four-helix bundle structure in the P6422 crystal (PDB code: 1lkv). FliGM and FliGCN of the subunit colored by cyan form the FliGM-FliGCN units with FliGCN and FliGM of the subunit colored by yellow, respectively, and FliGM and FliGCN of the subunit colored by green form the FliGM-FliGCN units with FliGCN and FliGM of the subunit colored by orange, respectively. (C) Stereo view of the molecular packing of Aa-FliG in the P21 crystal (PDB code: 3hjl), projected down the c axis. The molecules related by crystallographic 21 symmetry are colored by cyan and yellow. The cyan molecule located in the centre of the panel is labeled, and helix n and helix E of the center molecule are highlighted in orange.

(2.96 MB TIF)

Data collection statistics.

(0.04 MB PDF)

Refinement statistics.

(0.03 MB PDF)