Abstract

Background

Marijuana use is typically initiated during adolescence, which is a critical period for neural development. Studies have reported reductions in prepulse inhibition (PPI) among adults who use marijuana chronically, although no human studies have been conducted during the critical adolescent period.

Methods

This study tested PPI of acoustic startle among adolescents who were either frequent marijuana Users or naïve to the drug (Controls). Adolescents were tested using two intensities of prepulses (70 and 85 dB) combined with a 105 dB startle stimulus, delivered across two testing blocks.

Results

There was a significant interaction of group by block for PPI; marijuana Users experienced a greater decline in the PPI across the testing session than Controls. The change in PPI of response magnitude for Users was predicted by change in urine THC/creatinine after atleast 18 hours of abstinence, the number of joints used during the previous week before testing, as well as self-reported DSM-IV symptoms of marijuana tolerance, and time spent using marijuana rather than participating in other activities.

Conclusions

These outcomes suggest that adolescents who are frequent marijuana users have problems maintaining of prepulse inhibition, possibly due to lower quality of information processing or sustained attention, both of may contribute to maintaining continued marijuana use as well as attrition from marijuana treatment.

Keywords: prepulse inhibition, acoustic startle response, marijuana, cannabis, human, adolescence

1.0 Introduction

Marijuana is a commonly abused illicit drug that is typically first used during adolescence. In the United States there are roughly 2.5 million new marijuana users annually and about 75% of these new users are age 18 or younger (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2004). Over 40 percent of high school seniors have used marijuana at least once and 5% use marijuana on a daily basis (Johnston et al., 2008). The initiation of marijuana use is considered “especially crucial, as it often marks the first use of an illegal substance, and may presage future use of high-risk drugs such as cocaine, crack, or heroin” (Ellickson et al., 2004; p. 977). Alternatively, initiation of marijuana use may reflect an underlying genetic, physiological, and/or cognitive vulnerability to engaging in a variety of impulsive, disinhibited behaviors, including drug use (Iacono et al., 2008; Vanyukov et al., 2003, 2009). Initiation of marijuana use during adolescence is especially concerning because of the possibility for disruption of the rapid neural development occurring during this period. Research with animal models has demonstrated that exposure to THC (i.e., delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol; the primary psychoactive compound in marijuana) during adolescence results in changes in brain morphology and cognitive function lasting into adulthood (Jager and Ramsey, 2008; Realini et al., 2009; Rubino and Parolaro, 2008; Rubino et al., 2009; Schneider, 2008; Trezza et al., 2008). These changes in brain development and information processing may account for the variety of poor psychosocial outcomes associated with adolescent marijuana use, which includes school dropout, job instability, disruption of family systems, mental health problems, use of other illicit drugs, and involvement in crime (Fergusson et al., 2002; Hall and Solowij, 1998).

Prepulse inhibition of the acoustic startle response is a psychophysiological measure that may be important for understanding the effects of marijuana use on information processing. Prepulse inhibition (PPI) of startle involves an attenuation of responsiveness to a sudden-onset high-intensity stimulus when the stimulus immediately preceded by a lower intensity stimulus (Hoffman and Searle, 1965, 1968). In a healthy individual, presentation of the low-intensity stimulus activates a sensorimotor inhibition mechanism that protects processing from being interrupted by the high-intensity stimulus. Sensorimotor inhibition is considered to be an early process of stimulus evaluation that acts as a perceptual filter, allowing some stimuli to pass through for further processing while filtering out other less relevant stimuli (Boutros et al., 2004). Specifically, as stimuli are initially perceived, two automatic processes are initiated: one to identify the stimulus; and another to protect information processing of this stimulus from interruption (Graham, 1975, 1992). The degree to which the protective process is activated determines the efficiency of information filtering for protecting higher-order processing and is measured as the magnitude of PPI. Additionally, the efficiency of this mechanism is modulated by attention, with greater attention resulting in more efficient prepulse inhibition (Filion et al., 1993). Inefficient sensorimotor inhibition or poor attentional modulation can result in susceptibility to distraction by environmental cues, overwhelming higher-order information processing centers with irrelevant information (Boutros et al., 2004; Venables, 1964), ultimately resulting in ineffective behavioral organization and, in some situations, poor psychosocial outcomes (Kumari et al., 2005). As such, there has been a great deal of interest in using PPI measures of sensorimotor inhibition for exploring aspects of early information processing and its relationship to psychosocial outcomes in a variety of clinical conditions. For instance, PPI has been widely used in schizophrenia research as a “robust quantitative phenotype that is useful for probing the neurobiology and genetics of gating deficits in schizophrenia” (Swerdlow et al., 2008; p. 376). There is also reason to expect the PPI would be a useful tool for testing effects of marijuana use as well.

Recently, there has been great interest in the relationship of marijuana use and development of schizophrenia (for a review see Solowij and Michie, 2007), with research suggesting that marijuana use during adolescence leads to a six-fold increase in the likelihood of developing schizophrenia later in life (Andréasson et al., 1987). The proposed mechanism of this relationship is that the frequent use of marijuana during adolescence may exacerbate problems among those individuals with an underlying vulnerability for development of schizophrenia spectrum disorders (Luzi et al., 2008). This raises the question of whether the PPI disruption that has been widely reported in schizophrenia may, in some cases, actually be a consequence of preceding marijuana use.

Because there are very few studies of the relationship of marijuana use and PPI among humans, the animal literature offers some key insights on the topic. In tests of marijuana effects on PPI using animal models, most (Mansbach et al., 1996; Martin et al., 2003; Schneider and Koch, 2002; Wegener et al., 2008), but not all (Stanley-Cary et al., 2002) studies report decreases in PPI following acute administration of drugs that mimic the effects of marijuana (i.e., cannabinoid receptor 1 agonists). Further, vulnerability to marijuana’s effects on PPI appears to be specific to certain developmental periods. For instance, PPI is reduced among adult rats following chronic cannabinoid receptor 1 agonist exposure beginning during adolescence (Schneider and Koch, 2003; Schneider et al., 2005; Wegener and Koch, 2009), but adult rats experience no effects on PPI if marijuana exposure is limited to either prenatal (Bortolato et al., 2006) or adult (Schneider and Koch, 2003) developmental periods. The proposed biological mechanism of this developmentally specific effect is marijuana exposure activates the endocannabinoid system and subsequently alters the major remodeling of the cortical and limbic circuits occurring during adolescence (Jager and Ramsey, 2008; Realini et al., 2009; Rubino and Parolaro, 2008; Schneider, 2008). The specific effect of adolescent marijuana exposure in animals are pertinent to the current investigation because, PPI is a robust cross-species phenomenon (Braff et al., 2001) that is likely to inform human studies of adolescent marijuana user. Findings from animal studies raise important questions about the effects that marijuana use has on PPI in humans, particularly use during adolescence.

The investigation into marijuana effects on PPI in humans has been limited to only a few studies of adult marijuana users. One study of adults found no significant difference in PPI between chronic marijuana users and healthy controls (Quednow et al., 2004). However, based on the self-reported duration of use in this study (Quednow et al., 2004) it appears that the average age of onset of marijuana use was 19 years of age, which might be beyond the critical adolescent exposure period found to be important in the animal studies. In studies of adults who initiated their marijuana use during adolescence, chronic marijuana users were reported to experience significantly decreased PPI relative to healthy controls (Kedzior and Martin-Iverson, 2006, 2007; Scholes and Martin-Iverson, 2009). We are not aware of any study which has examined PPI among adolescent marijuana users.

The purpose of the current study was to evaluate the relationship between PPI and marijuana use in adolescents who were either frequent users of marijuana or non-users. Based on the previous literature on chronic marijuana exposure in adult human (Kedzior and Martin-Iverson, 2006, 2007; Scholes and Martin-Iverson, 2009) and animal (Schneider and Koch, 2003; Schneider et al., 2005; Wegener and Koch, 2009) studies, it was expected that adolescent marijuana users would experience diminished PPI relative to non-users.

2.0 Methods

2.1 Participants

Adolescents were recruited from the community of Winston-Salem, North Carolina to participate in a study of marijuana users and healthy controls. Potential participants were identified from respondents to local radio and television advertisements for “a research study comparing how using or not using marijuana affects attention and problem solving.” A thorough description of the characteristics of respondents to these types of advertisements has been reported elsewhere (Shannon et al., 2007). Adolescents and their parent or legal guardian were first interviewed over the telephone regarding general demographic and health characteristics. Those respondents who were interested and appeared generally suitable for participation were invited for a more comprehensive on-site interview to determine their eligibility for participation.

2.2 Screening procedures

The on-site screening evaluation began with an interview conducted to collect written informed consent and information about physical and psychiatric health, drug/alcohol use history, and intelligence. Physical health was evaluated by a physician assistant who conducted a physical examination after collecting a detailed health history. Psychiatric status of the adolescent was assessed by the Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia: Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL; Kaufman et al., 1997), interviewing both the adolescent and the parent/legal guardian. A board-certified child and adolescent psychiatrist (Dr. Dawes) reviewed and made the final determination on all psychiatric diagnoses. Adolescents were interviewed about their current and lifetime substance use. For adolescents reporting marijuana use, the Modified Substance Use Disorders Module of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Disorders (SCID; First et al., 2001) was administered to determine whether participants met criteria for Cannabis Abuse or Dependence. Self-report information regarding substance use was obtained only from the adolescent and was not shared with the parent/legal guardian. Breath alcohol (AlcoTest® 7110 MKIII C; Draeger Safety Inc., Durango, CO) and urine tests for use of marijuana, amphetamine, cocaine, and benzodiazepines (Redwood Biotech, Santa Rosa, CA) were obtained. Finally, intelligence was tested using the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (Psychological Corporation, 1999).

Adolescents were eligible to participate of they were healthy, 14 to 17 years of age, and used marijuana frequently (4+ days per week for at least last 6 months; User group) or never used marijuana (Control group). Exclusion criteria included any physical condition that would interfere with interpretation of study outcomes (e.g., head injury, seizure disorder, etc.), current or past DSM-IV Axis I psychiatric disorder, IQ < 70, or more than 50 episodes of any drugs of abuse. The exception to these criteria was that those in the Cannabis User group were not excluded if they had more than 50 episodes of cannabis use or met DSM-IV criteria for Cannabis Abuse or Dependence. Based on these criteria potential participants were excluded for use of other drugs (nicotine n = 3, cocaine n = 3, and alcohol n = 1), low intelligence (n = 8), pregnancy (n = 2), meningitis (n = 1), head-injury (n = 2), and other psychiatric disorder (n = 5).

The Institutional Review Boards of Wake Forest University Health Sciences and The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio approved study procedures, which were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.3 Experimental Procedures

Adolescents enrolled in the study were scheduled to return for experimental testing on the day immediately following screening. The second day involved additional urine-drug analyses and psychophysiological testing. Adolescents were paid $125 for the two days of participation and the parents were paid $50 for completing the screening report about their adolescent.

2.3.1 Abstinence from Drug Use

The study was designed to collect PPI measures after at least 18 hours of abstinence from marijuana use. To achieve this outcome, participants were instructed to abstain from marijuana (and all illicit drugs) use between the consecutive screening and experimental testing days. Marijuana Users were informed that they would receive an additional $25 for successful abstinence from drug use. As on the screening day, breath-alcohol and urine-drug tests were conducted to verify abstinence of drug use. Additionally, quantitative measures of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and creatinine from both the screening and experimental day were tested by a reference lab (NorChem Drug Testing; Flagstaff, AZ). An increase of greater than 50% in the ratio of THC to creatinine from the screening day to the experimental day was interpreted as evidence of marijuana use between the screening and experimental sessions (Huestis and Cone, 1998). Four participants were excluded for suspected marijuana use during the abstinence period. During the confirmed-abstinence period, marijuana craving was assessed using the Marijuana Craving Questionnaire (Heishman et al., 2001).

2.4 Physiological Recording

Magnitude of the startle eyeblink response to auditory stimulation was recorded based on recommended standards for the human acoustic startle response (Blumenthal et al., 2005). All physiological recording was conducted between 11:00 am and 1:00 pm. During the two hours prior to physiological recording, participants were in the laboratory and refrained from eating, drinking, and strenuous physical exertion. All testing was conducted within a light and sound attenuated room that was maintained at a comfortable temperature. Prior to testing brief hearing screening was conducted to confirm that the participants hearing threshold was < 45 decibels. For the PPI testing, participants were instructed to listen to the stimuli, but make no overt response, and to keep their eyes open while gazing at a fixation point 2 m away that was at eye level.

2.4.1 Instrumentation

All physiological recordings were conducted using the Human Acoustic Startle system (Coulbourn Instruments, Allentown, PA). The eyeblink response was recorded from the electromyographic measurement of activity of the orbicularis oculi using disposable solid gel silver/silver chloride electrodes (Ambu® Neuroline 700, Glen Burnie, MD) at the standard placement (Fridlund and Cacioppo, 1986). This signal was collected at a rate of 1 sample per ms and processed using a V75-04 bioamplifier. The electromyographic signal was amplified (10,000 gain), filtered (28 – 500 Hz passband; van Boxtel et al., 1998), rectified, and smoothed with a contour following integrator with a 10 ms time constant (Blumenthal, 1994). Electromyographic (EMG) responses were recorded and analyzed within a window of 20 – 200 ms following the stimulus onset. This EMG response was compared to a baseline defined as the mean EMG activity 20 ms immediately preceding stimulus onset. This analysis window was selected to minimize the chance of coding a spontaneous blink as event-related (Blumenthal et al., 2005).

2.4.2 Auditory Stimuli

Three intensities of auditory “white noise” stimuli were generated using a Coulbourn V85-05 Audio Source Module: 105, 85, and 70 decibels (dB). All stimuli were presented for 50 ms (< 1 ms rise/fall time) and delivered binaurally through headphones (HD 280 Pro; Sennheiser GmbH and Co. KG, Wedemark, Germany) above a 60 dB background masking noise. A calibration check of the sound pressure level was conducted monthly (Quest 2200 Sound Level Meter with earphone coupler EC-9A + QC-10; Quest Technologies, Oconomowoc, WI).

Auditory stimulation and recording was conducted across 2 testing blocks. The first and second blocks were each composed of 4 trials of each stimulus type: 105 dB only (Startle trial), 70 dB followed by 105 dB (70 dB Prepulse trial), and 85 dB followed by 105 dB (85 dB Prepulse trial). Blocks were separated by a two minute rest period during which the 60 dB masking noise continued to be delivered. The two intensities of prepulse were used to test for any effects of marijuana use on the commonly reported finding that PPI of magnitude increases with increasing intensity prepulse stimuli (e.g. Blumenthal, 1995; Graham and Murray, 1977). Presentation order of each trial type was pseudo-randomized so that no more than two of the same trial types appeared consecutively. Inter-trial intervals ranged from 17 – 20 sec in duration, the order of which was randomized and arranged so that no more than two consecutive inter-trial intervals were of the same duration. There was a 120-ms delay between the onsets of the prepulse (85 or 70 dB noise) and the 105 dB startle noise. Finally, the very first trial was a 105 dB noise that was analyzed individually (not included in Block analyses) as a measure of initial startle reactivity (Grillon et al., 2000).

2.5 Data Analyses

Participant characteristics were compared between groups using chi-square test (gender), Fisher’s Exact Test (race), and two-tailed independent samples t-tests for dimensional variables (age and IQ). A repeated-measures analyses of variance (ANOVA) was used to test consecutive THC/creatinine levels from the screening and experimental testing days.

Two aspects of the EMG response were analyzed: magnitude and probability. Magnitude was calculated as the difference between the greatest EMG voltage within the scoring window and the pre-stimulus baseline. These raw magnitude scores (arbitrary units) were used to analyze the acoustic startle reactivity on the Startle trials. For PPI analyses, these magnitude scores were analyzed as a percent change in arbitrary units from the Prepulse (85 or 70 dB noise) to the Startle trials (Blumenthal et al., 2004). If peak response was not at least twice as large as the mean of the pre-stimulus baseline, the magnitude for this individual trial was coded as zero (see Blumenthal et al., 2005 for discussion of response criterion). These zero level responses were included in the calculation of the block averages for magnitude for each stimulus condition. Startle response probability was defined as the percentage of trials with a non-zero magnitude in each stimulus condition.

The hypotheses that the User group would have diminished PPI relative to the Control group was tested using two repeated-measures ANOVAs (1 each for magnitude and probability): involving tests of Group X Intensity X Block. For these tests, there were 2 levels of group (User and Control), intensity of pre-stimulus (70–105 dB and 85–105 dB), and block (trials before and after rest break). Follow-up comparisons were tested simultaneously with the omnibus test using SPSS post hoc code (University of Arizona, 2010). Cohen’s d is reported as a measure of effect size for these primary analyses (Cohen, 1992).

To test the relationship between PPI of magnitude and drug use characteristics we performed multiple linear regression using the stepwise selection method. Because the change of PPI from Block 1 to Block 2 differentiated the Users from Controls, average change scores (Block 1 – Block 2) were calculated for PPI of magnitude. This change in PPI of magnitude was the dependent variable and marijuana use variables were independent variables in the model. The t-test, β coefficient, and 95% confidence interval for each predictor are reported. Residuals of the model departed from zero in a symmetric pattern and the error variance was constant, indicating that the model assumption was met.

The magnitude of the startle response to the very first trial (105 dB only) was compared across the two groups using a two-tailed independent samples t-test (i.e., Startle Reactivity analyses). Repeated-measures ANOVAs were used to analyze 105 dB-only trials with Block entered as a within-subject variables and Group as the between-subject variable. All analyses were conducted using PASW Statistics version 17.0.2 (SPSS inc., Chicago, IL).

3.0 Results

3.1 Participant Characteristics

Seventy-eight adolescents completed the study and were retained for all analyses. Thirty-four participants were recruited in the marijuana User group and 44 participated in the Control group. As shown in Table 1, there were no significant group differences in age, gender, or racial/ethnic profile, although the User group had significantly lower verbal IQ than Controls.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Marijuana Users and non-user Controls

| Characteristic | Control n = 44 |

User n = 34 |

Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | t | p | |

| Age | 16.1 | (0.9) | 16.1 | (0.9) | 0.128 | .898 |

| Verbal IQ | 101.2 | (13.2) | 94.1 | (10.3) | 2.524 | .014 |

| Performance IQ | 99.4 | (12.4) | 96.4 | (10.2) | 1.100 | .275 |

| Number | (%) | Number | % | χ2 | p | |

| Gender | 0.601 | .438 | ||||

| Male | 26 | (59) | 23 | (60) | ||

| Female | 18 | (41) | 11 | (40) | ||

| Race | .101f | |||||

| African-American | 13 | (29) | 16 | (47) | ||

| Caucasian | 27 | (62) | 18 | (53) | ||

| Other/More than one Race | 4 | (9) | 0 | (0) | ||

Fisher’s Exact Test

Note. IQ scores were standardized intelligence quotient scores from the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence.

3.1.1 Marijuana Use

Additional analyses were conducted to characterize marijuana use of the User group. Of those recruited into the User group, 9 (26%) met DSM-IV criteria for Cannabis Abuse and another 15 (44%) met criteria for Cannabis Dependence. None of the participants met DSM-IV criteria for abuse or dependence of nicotine, alcohol, stimulants, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, or hallucinogens. On average, participants in the User group smoked marijuana 6 days a week (SD = 1.1) and initiated regular ongoing use of marijuana at age 14.9 (SD = 0.9). On the day of physiological testing, the average THC/creatinine ratio measured in the urine was 1.33 ng/ml (SD = 1.44), which was a significant reduction relative to the preceding screening day’s measurement (F1,30 = 12.3, p = .001, d = .32; User M = 1.87, SD = 1.94).

3.2 Psychophysiological Outcomes

3.2.1 Acoustic Startle

All participants had 100% probability of responding to the very first 105 dB trial, except one marijuana user whose recording had an artifact on this trial. The magnitude of response to this first trial did not significantly differ between the two groups (t75 = 0.286, p = .775; User M = 32.6, SD = 22.2; Control M = 34.2, SD = 26.1).

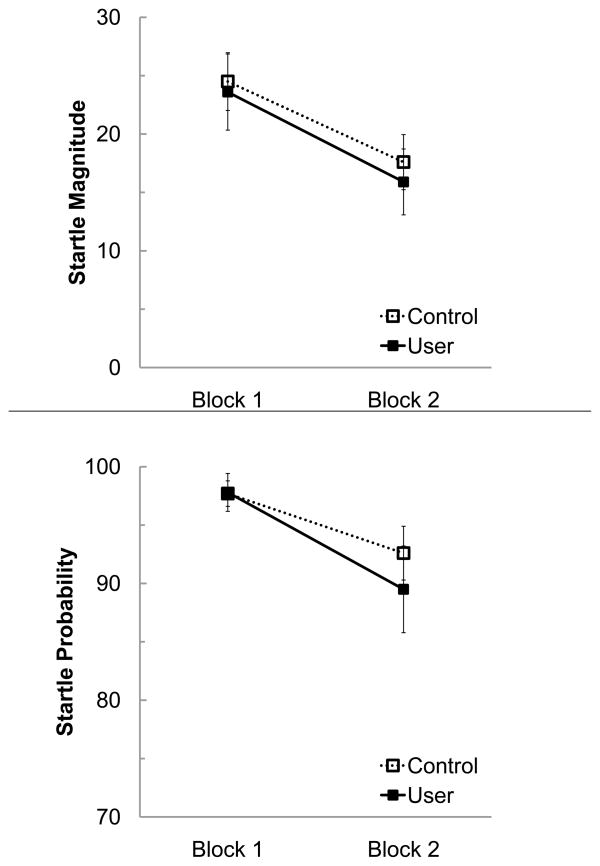

There were no significant group differences or interactions for responses on either of the blocks of 105 dB trials. Specifically, the groups did not differ in average peak startle response across the two blocks in terms of magnitude (F1,76 = 0.12, p = .729) or probability (F1,76 = 0.575, p = .451) (see Figure 1). Independent of group status, there was a significant main effect of Block, with a reduction in magnitude (F1,76 = 49.09, p < .001, d = .36) and probability (F1,76 = 10.03, p = .002, d = .13) of startle response from Block 1 to Block 2.

Figure 1.

Startle Magnitude (top panel) and Probability (bottom panel) for Marijuana Users and Controls. Data are presented by Block and there was a significant reduction in Magnitude and Probability across the two Blocks.

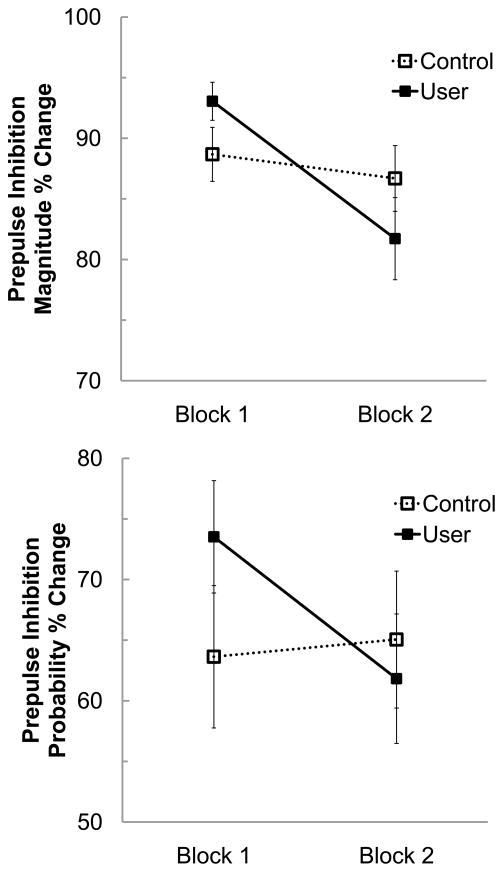

3.2.2 Prepulse Inhibition

The groups differed in the prepulse inhibition across the two blocks of testing. While the Control group had a relatively stable PPI across the two testing blocks, the User group experienced significant reduction in PPI of response magnitude and probability from Block 1 to Block 2, irrespective of prepulse stimulus intensity (see Figure 2). This effect was demonstrated by a significant Group by Block interaction for both PPI of magnitude (F1,76 = 8.00, p = .006) and probability (F1,76 = 9.12, p = .003). These effects remained significant even after covarying WASI verbal IQ and THC/creatinine ratio from the experimental testing day (PPI of magnitude F1,74 = 5.89, p = .018; PPI of probability F1,74 = 5.72, p = .019). Follow-up comparisons showed a significant decline in PPI of magnitude from the first to second testing blocks for the User group (mean difference = 11.34, p < .001, d = .74) but not the Control group (mean difference = 1.99, p = .365, d = .12). A similar effect was observed for analyses of PPI of response probability (User mean difference = 12.19, p = .001, d = .42; Control mean difference = 1.42, p = .635, d = .04). The two groups did not differ in PPI of magnitude or probability at Block 1.

Figure 2.

Prepulse Inhibition of Startle Magnitude (top panel) and Probability (bottom panel) for Marijuana Users and Controls. Data are presented by Block and there was a significant interaction of Group by Block for Prepulse Inhibition of Magnitude and Probability.

The intensity of the prepulse stimulus had a significant effect on the PPI of response magnitude and probability, and this effect was similar for both groups. As expected, there was greater PPI of response magnitude and probability for the 85 dB relative to the 70 dB condition. There was as significant main effect of decibel level on PPI of magnitude (F1,76 = 12.91, p = .001, d = .34) and PPI of probability (F1,76 = 32.87, p < .001, d = .38) and there was no interaction with Group (magnitude p = .778 and probability p = .755).

3.3 Relationship of Marijuana Use to Change in Prepulse Inhibition across Blocks

There was a significant relationship between the change in PPI over the two blocks and several marijuana use characteristics. Over half of the variance in change of PPI of magnitude for the user group (R2 = 0.56; N = 34) was predicted by the combination of the change in urine THC/creatinine measured between screening and experimental testing days (9%), the number of joints smoked in the last week (5%), as well as current DSM-IV symptoms of marijuana tolerance (26%), and time spent using marijuana rather than participating in other activities (17%). There were no significant relationships of change in PPI of magnitude with marijuana craving or duration of marijuana use.

4.0 Discussion

Contrary to the hypotheses, there were no group differences in the overall magnitude or probability of prepulse inhibition (PPI). However, PPI decreased more quickly for the User group than the Control group. The decrease in PPI for the User group is interpreted as representing a rapid decline in the quality of information processing or sustained attention across the testing session. Further, the change in PPI of magnitude across the two testing blocks was related to some, but not all, drug use characteristics of the frequent user group.

Previous research has shown that the proportion of inhibition of startle (percent PPI) remains constant across trials while the amount of PPI decreases across trials, due to habituation of the startle response (Blumenthal, 1994, 1997, 1999; Lipp and Krinitzky, 1998; however, see Quednow et al., 2006 for an alternative conclusion). With the limited number of trails in the current study one would reasonably expect a slight decline in PPI, as was observed in the Control group. The User group experienced a significant decline in PPI of magnitude from Block 1 to 2 and this decrease was related to the number of drug use variables. For these reasons, the failure to sustain PPI in the User group and the speed at which this effect occurred is interpreted as representing a deficit in PPI of magnitude. The deficit of PPI later in the session in the User group suggests a decrease in the quality of information processing across the session in these participants, which may be reflective of a problem with sustained attention. This effect on PPI observed in this block design study of marijuana using adolescents is generally consistent with the conclusion from previous studies showing adult marijuana users fail to sustain attention to the auditory stimuli of a PPI task, resulting decreased PPI of magnitude relative to controls (Scholes and Martin-Iverson, 2009). However, direct comparisons to previous adult studies are not possible, as the previous studies used a single block design (Kedzior and Martin-Iverson, 2006, 2007; Quednow et al., 2004).

In addition to the group differences, the change in PPI of magnitude among the frequent marijuana users was predicted by particular characteristics of current marijuana use. Specifically, the deficit of PPI is related to both recent marijuana use characteristics and current DSM-IV symptoms. A decrease of PPI was greater among Users with more days in the past week of marijuana use, greater decline in the THC/creatinine ratio after abstinence from marijuana, more self-reported symptoms of tolerance, and time spent using marijuana (to the exclusion of other activities). However, decrease of PPI was not related to age of onset or duration of use of marijuana or marijuana craving during the abstinence period. These outcomes are consistent with recent reports that the disruption of PPI among adults with chronic marijuana use is related to more frequent use of marijuana during the last 30 days, but not related to lifetime duration of chronic use (Scholes and Martin-Iverson, 2009). Given these results, it would be interesting to determine whether the relationships identified with decrease of PPI remained after longer periods of abstinence. Previous research has reported that adult chronic marijuana users experience impairments in performance of neuropsychological measures of attention after brief periods (about 24 hours) of abstinence from the drug, although they appear to recover from these impairments after longer periods of abstinence (Pope and Yurgelun-Todd, 1996). However, since the modal onset of daily marijuana use is 7th grade (Johnston et al., 2008) the challenging is getting the more frequent users, like our sample, to ever experience abstinence for periods sufficient for this impairment to abate. Therefore, if these adolescents never experience an abstinence period sufficient to recover from the acute effects of cannabis on information processing, these deficits in the quality of information processing may in fact be acting to maintain frequent use. This hypothesis is supported from reports that have relied on more global measures of information processing than those used here, which showed that retention in treatment programs for marijuana dependence is inversely related to information processing (Aharonovich et al., 2008). Therefore one interpretation of the current findings is that, in the short-term, marijuana use impairs some aspects of information processing (measureable as PPI), which facilitates further marijuana use and/or makes it more difficult to abstain from marijuana use for longer periods of time.

There were several limitations or, at the very least, important caveats to keep in mind when interpreting the results of this study. First, a passive PPI paradigm was used, which did not carry the full attentional load that has been found to produce more robust results in previous studies of adult marijuana use (Kedzior and Martin-Iverson, 2006; Scholes and Martin-Iverson, 2009) or allow for direct tests of attentional modulation of PPI. Second, this study measured PPI among frequent marijuana users after about 18 hours of verified abstinence. The timing of the PPI measurement is critical when relating these results to previous studies, which collected PPI measures either during the time frame that would correspond to either acute intoxication or during withdrawal from marijuana (Kedzior and Martin-Iverson, 2006; Quednow et al., 2004). The duration of the abstinence period may influence the observed PPI findings for the User group and different abstinence periods may produce larger or smaller effects. Third, the study had a fairly restrictive sampling criterion in terms of marijuana use (4+ days per week for at least six months with no other substance use involvement), as well as gender and racial distribution. This limits generalizability and raises questions for future studies to test effects of different periods of marijuana exposure during adolescence, concurrent exposure to marijuana and other drugs of abuse, and gender or racial differences in these effects.

In conclusion, this study found a more rapid decline in the PPI of startle response magnitude and probability for frequent marijuana users than was observed in the Control group. This finding may be interpreted as reflecting a progressive reduction in the quality of information processing or failure of sustained attention across the session for the marijuana user group. Changes in PPI were related to recent marijuana use patterns and DSM-IV marijuana use symptoms. These deficits may account for the acute problems with attention and retention in marijuana treatment that have been reported previously, and may play an important part in the maintenance of regular use of marijuana by adolescents.

Table 2.

Drug Use Characteristics as Predictors of change in PPI of Magnitude

| Predictor Variable | t | β coefficient | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activities Reduced | 2.72 | 16.84 | 4.09, 29.59 |

| THC/creatinine | 2.55 | 5.51 | 1.07, 9.94 |

| Tolerance | 2.67 | 9.84 | 2.28, 17.42 |

| Joints/week | 2.33 | 2.07 | 0.25, 3.89 |

Activities Reduced = DSM-IV criteria for time spent using marijuana rather than participating in other activities; THC/creatinine = change in urine THC/creatinine measured between screening and experimental testing days; and Tolerance = DSM-IV criteria for marijuana tolerance.

Note: df for all t-tests was 33.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aharonovich E, Brooks AC, Nunes EV, Hasin DS. Cognitive deficits in marijuana users: Effects on motivational enhancement therapy plus cognitive behavioral therapy treatment outcome. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;95:279–283. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andréasson S, Allebeck P, Engström A, Rydberg U. Cannabis and schizophrenia. A longitudinal study of Swedish conscripts. Lancet. 1987;2:1483–1486. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)92620-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal TD. Signal attenuation as a function of integrator time constant and signal duration. Psychophysiology. 1994;31:201–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1994.tb01041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal TD. Prepulse inhibition of the startle eyeblink as an indicator of temporal summation. Percept Psychophys. 1995;57:487–494. doi: 10.3758/bf03213074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal TD. Prepulse inhibition decreases as startle reactivity habituates. Psychophysiology. 1997;34:446–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1997.tb02388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal TD. Short lead interval startle modification. In: Dawson ME, Schell AM, Bohmelt AH, editors. Startle Modification: Implications for Neuroscience, Cognitive Science, and Clinical Science. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1999. pp. 6–20. [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal TD, Cuthbert BN, Filion DL, Hackley SA, Lipp OV, van Boxtel A. Committee report: guidelines for human startle eyeblink electromyographic studies. Psychophysiology. 2005;42:1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2005.00271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal TD, Elden A, Flaten MA. A comparison of several methods used to quantify prepulse inhibition of eyeblink responding. Psychophysiology. 2004;41:326–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2003.00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortolato M, Frau R, Orrù M, Casti A, Aru GN, Fà M, Manunta M, Usai A, Mereu G, Gessa GL. Prenatal exposure to a cannabinoid receptor agonist does not affect sensorimotor gating in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;531:166–170. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutros NN, Korzyukov O, Jansen B, Feingold A, Bell M. Sensory gating deficits during the mid-latency phase of information processing in medicated schizophrenia patients. Psychiatry Res. 2004;126:203–215. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braff DL, Geyer MA, Swerdlow NR. Human studies of prepulse inhibition of startle: normal subjects, patient groups, and pharmacological studies. Psychopharmacology. 2001;156:234–258. doi: 10.1007/s002130100810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson PL, Tucker JS, Klein DJ, Saner H. Antecedents and outcomes of marijuana use initiation during adolescence. Prev Med. 2004;39:976–984. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Swain-Campbell N. Cannabis use and psychosocial adjustment in adolescence and young adulthood. Addiction. 2002;97:1123–1135. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filion DL, Dawson ME, Schell AM. Modification of the acoustic startle-reflex eyeblink: a tool for investigating early and late attentional processes. Biol Psychol. 1993;35:185–200. doi: 10.1016/0301-0511(93)90001-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-patient Edition (SCID-I/NP) Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fridlund AJ, Cacioppo JT. Guidelines for human electromyographic research. Psychophysiology. 1986;23:567–589. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1986.tb00676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham FK. The more or less startling effects of weak prestimulation. Psychophysiology. 1975;12:238–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1975.tb01284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham FK. Attention: the heartbeat, the blink, and the brain. In: Campbell BA, Hayne H, Shvyrkov VB, editors. Neural Mechanisms of Goal-Directed Behavior and Learning. Academic Press; New York: 1992. pp. 511–519. [Google Scholar]

- Graham FK, Murray GM. Discordant effects of weak prestimulation on magnitude and latency of the reflex blink. Physiol Psychol. 1977;5:108–114. [Google Scholar]

- Grillon C, Sinha R, Ameli R, O’Malley SS. Effects of alcohol on baseline startle and prepulse inhibition in young men at risk for alcoholism and/or anxiety disorders. J Stud Alcohol. 2000;61:46–54. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall W, Solowij N. Adverse effects of cannabis. Lancet. 1998;352:1611–1616. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)05021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heishman SJ, Singleton EG, Liguori A. Marijuana Craving Questionnaire: development and initial validation of a self-report instrument. Addiction. 2001;96:1023–1034. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.967102312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman HS, Searle JR. Acoustic variables in the modification of startle reaction in the rat. J Comp Exp Psychol. 1965;60:53–58. doi: 10.1037/h0022325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman HS, Searle JR. Acoustic and temporal factors in the evocation of startle. J Acoustic Soc Am. 1968;43:269–282. doi: 10.1121/1.1910776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huestis MA, Cone EJ. Differentiating new marijuana use from residual drug excretion in occasional marijuana users. J Anal Toxicol. 1998;22:445–454. doi: 10.1093/jat/22.6.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, Malone SM, McGue M. Behavioral disinhibition and the development of early-onset addiction: common and specific influences. Ann Rev Clin Psychol. 2008;4:325–348. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jager G, Ramsey NF. g-term consequences of adolescent cannabis exposure on the development of cognition, brain structure and function: an overview of animal and human research. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2008;1:114–123. doi: 10.2174/1874473710801020114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Secondary school students (NIH Publication No. 08-6418A) I. National Institute on Drug Abuse; Bethesda, MD: 2008. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, Ryan N. Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children- present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedzior KK, Martin-Iversion MT. Chronic cannabis use is associated with attention-modulated reduction in prepulse inhibition of the startle reflex in healthy humans. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20:471–484. doi: 10.1177/0269881105057516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedzior KK, Martin-Iversion MT. Attention-dependent reduction in prepulse inhibition of the startle reflex in cannabis users and schizophrenia patients –a pilot study. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;560:176–182. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari V, Das M, Hodgins S, Zachariah E, Barkataki I, Howlett M, Sharma T. Association between violent behaviour and impaired prepulse inhibition of the startle response in antisocial personality disorder and schizophrenia. Behav Brain Res. 2005;158:159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipp OV, Krinitzky SP. The effect of repeated prepulse and reflex stimulus presentations on startle prepulse inhibition. Biol Psychol. 1998;47:65–76. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0511(97)00019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luzi S, Morrison PD, Powell J, di Forti M, Murrary RM. What is the mechanism whereby cannabis use increases risk of psychosis? Neurotox Res. 2008;14:105–112. doi: 10.1007/BF03033802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansbach RS, Rovetti CC, Winston EN, Lowe JA., III Effects of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist SR141716A on the behavior of pigeons and rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996;124:315–322. doi: 10.1007/BF02247436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin RS, Secchi RL, Sung E, Lemaire M, Bonhaus DW, Hedley LR, Lowe DA. Effects of cannabinoid receptor ligands on psychosis-relevant behavior models in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;165:128–135. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1240-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope HG, Jr, Yurgelun-Todd D. The residual cognitive effects of heavy marijuana use in college students. JAMA. 1996;275:521–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychological Corporation. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence®. The Psychological Corporation: Harcourt Brace and Company; San Antonio, TX: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Quednow BB, Kühn K-U, Beckmann K, Westheide J, Maier W, Wagner M. Attenuation of the prepulse inhibition of the acoustic startle response within and between sessions. Biol Psychol. 2006;71:256–263. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quednow BB, Kühn KU, Hoenig K, Maier W, Wagner M. Prepulse inhibition and habituation of acoustic startle response in male MDMA (‘Ecstasy’) users, cannabis users, and healthy controls. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:982–990. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Realini N, Runino T, Paarolaro D. Neurobiological alterations at adult age triggered by adolescent exposure to cannabinoids. Pharmacol Res. 2009;60:132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubino T, Parolaro D. Long lasting consequences of cannabis exposure in adolescence. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2008;286:s108–113. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubino T, Realini N, Braida D, Guidi S, Capurro B, Viganò D, Guidali C, Pinter M, Sala M, Bartesaghi R, Parolaro D. Changes in hippocampal morphology and neuroplasticity induced by adolescent THC treatment are associated with cognitive impairment in adulthood. Hippocampus. 2009;19:763–772. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider M. Puberty as a highly vulnerable developmental period for the consequences of cannabis exposure. Addict Biol. 2008;13:253–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider M, Drews E, Koch M. Behavioral effects in adult rats of chronic prepubertal treatment with the cannabinoid receptor agonist WIN 55,212-2. Behav Pharmacol. 2005;16:447–454. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200509000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider M, Koch M. The cannabinoid agonist WIN 55,212–2 reduces sensorimotor gating and recognition memory in rats. Behav Pharmacol. 2002;13:29–37. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200202000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider M, Koch M. Chronic pubertal, but not adult chronic cannabinoid treatment impairs sensorimotor gating, recognition memory, and the performance in a progressive ratio task in adult rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:1760–1769. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholes KE, Martin-Iverson MT. Alternations to pre-pulse inhibition (PPI) in chronic cannabis users are secondary to sustained attention deficits. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;207:469–484. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1679-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon EE, Mathias CW, Marsh DM, Dougherty DM, Liguori A. Teenagers don’t always lie: characteristics and correspondence of telephone and in-person reports of adolescent drug use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;90:288–291. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solowij N, Michie PT. Cannabis and cognitive dysfunction: parallels with endophenotypes of schizophrenia? J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2007;32:30–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley-Cary CC, Harris C, Martin-Iverson MT. Differing effects of the cannabinoid agonist, CP 55,940, in an alcohol or Tween 80 solvent, on prepulse inhibition of the acoustic startle reflex in the rat. Behav Pharmacol. 2002;13:15–28. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200202000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2003 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-25, DHHS Publication No. SMA 04-3964; Rockville, MD: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow NR, Weber M, Qu Y, Light GA, Braff DL. Realistic expectations of prepulse inhibition in translational models for schizophrenia research. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;199:331–388. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1072-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trezza V, Coumo V, Vanderschuren LJMJ. Cannabis and the developing brain: insights from behavior. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;585:441–452. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- University of Arizona. [Accessed November 1, 2010];Post hoc Tests for Interactions using SPSS. 2001 http://www.u.arizona.edu/udocs/stat/spss/posthoc.html.

- van Boxtel A, Boelhouwer AJ, Bos AR. Optimal EMG signal bandwidth and interelectrode distance for the recording of acoustic, electrocutaneous, and photic blink reflexes. Psychophysiology. 1998;35:690–697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanyukov MM, Kirisci L, Moss L, Tarter RE, Reynolds MD, Maher BS, Kirillova GP, Ridenour T, Clark DB. Measurement of the risk for substance use disorders: Phenotypic and genetic analysis of an index of common liability. Behav Gen. 2009;39:233–244. doi: 10.1007/s10519-009-9269-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanyukov MM, Tarter RE, Kirisci L, Kirillova GP, Maher BS, Clark DB. Liability to substance use disorders: 1. Common mechanisms and manifestations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2003;27:507–515. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venables P. Input dysfunction in schizophrenia. In: Maher BA, editor. Progress in Experimental Personality Research. Academic Press; Orlando, FL: 1964. pp. 1–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegener N, Koch M. Behavioural disturbances and altered Fos protein expression in adult rats after chronic pubertal cannabinoid treatment. Brain Res. 2009;1253:81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.11.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegener N, Kuhnert S, Thüns A, Roese R, Koch M. Effects of acute systemic and intra-cerebral stimulation of cannabinoid receptors on sensorimotor gating, locomotion and spatial memory in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;198:375–385. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1148-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]