Abstract

Indoor combustion of crop residues for cooking or heating is one of the most important emission sources of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in developing countries. However, data on PAH emission factors (EFs) for burning crop residues indoor, particularly those measured in field were scarce, leading to large uncertainties in the emission inventories. In this study, EFs of PAHs for nine commonly used crop residues burnt in a typical Chinese rural cooking stove were measured in simulated kitchen. The measured EFs of total PAHs averaged at 63 ± 37 mg/kg, ranging from 27 to 142 mg/kg, which were higher than those measured in chamber experiments, implying that the laboratory experiment based emission and risk assessment should be carefully reviewed. EFs of gaseous and particulate phase PAHs were 27 ± 13 and 35 ± 23 mg/kg, respectively. Composition profiles and isomer ratios of emitted PAHs were characterized. Stepwise regressions found that modified combustion efficiency and fuel moisture were the most important factors affecting the emissions. 80 ± 6 % of PAHs were associated with PM2.5 and the mass percentage of PAHs in fine particles increased as the molecular weight increased. For freshly emitted PAHs, absorption into organic carbon, rather than adsorption, dominated the gas-particle partitioning.

Introduction

Total global emissions of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) were estimated at 520 Gg/year in 2004, among which over 80 % was from developing countries and more than half was from biomass burning (1). As a result, PAHs are still among the toxic organic pollutants of most concern in environment in developing countries. It was estimated that inhalation exposure to ambient air PAHs causes 1.6 % of total lung cancer morbidity in China (2). PAHs are primarily from incomplete combustions, and the main sources vary widely among countries. In rural areas of most developing countries, crop residues are widely used for cooking and house heating, resulting in not only the contribution to the total emission of many air pollutants, but also severe indoor air pollution in households (3). For example, biomass contributed more than 90 % and 60 % of total PAHs emissions in India and China, respectively (1). With the growth of population and energy consumption, it is expected that PAH emission from biomass burning will continue to increase (4).

Emission inventory of PAHs can be developed based on strengths of emission activities and emission factors (EFs), and the latter can be measured from combustion experiments. However, because of the differences in fuel properties and types (size, shape, moisture) and the diversities in various residential or industrial combustion stoves, as well as different experimental methods (field vs. laboratory chamber combustion, and controlled water boiling test vs. daily cooking practices), the reported EFs for a given fuel often vary several orders of magnitude, leading to high uncertainty in emission inventories (4–10).

Although PAH emissions from biomass occur mostly in developing countries, most EFs have been measured in developed countries (1). Unfortunately, emission of PAHs from indoor crop residue burning has not been well characterized and available data were mostly from chamber experiments for corn or wheat straw (4, 7). When the EFs measured in developed countries are applied to develop emission inventory for developing countries, bias is inevitable due to difference in combustion conditions (4, 12). Moreover, most EFs were measured for chamber experiments, rather than in real stoves (4–10). It was demonstrated that measurements of EFs under field conditions could be very different from those in chamber studies, and the former may provide more realistic results than the latter (6, 10, 13). Field burning activities in residential stoves often yielded higher emissions of pollutants due to limitation of air circulation, compared to those measured in laboratory (6, 8–10). It was reported that particle EFs in actual cooking activities were over three times higher than those from simulate experiment in laboratory (9). Hence, there is a desire for more studies focusing on the emissions and the health impacts of pollutants, including PAHs, from field combustion under actual conditions.

In this study, we focus on PAHs emissions from crop residue burning in a commonly used cooking stove in a typical kitchen setting in rural China. The objectives included: 1. estimating EFs of PAHs from crop residues of various kinds burnt at real environmental conditions; 2. investigating main factors affecting the emission; 3, characterizing the size distribution of particulate phase PAHs from indoor combustion; and 4. characterizing gas-particulate partitioning of freshly emitted PAHs.

Experiment

Cooking Stove and Crop Residues

A brick cooking stove which is commonly used in rural China is used in this study. The stove, connected to a “Kang” (heating bed) was built in a kitchen similar to those often found in villages in northern China (see the Supporting Information, S1). The kitchen and the stove are described elsewhere in detail (14). Nine commonly used crop residues (rice, wheat, corn, soybean, peanut, cotton, sesame, horsebean, and rape residue) were measured for PAH emissions. Fuel properties are listed in the S2.

Combustion experiments

The combustion experiment in the simulated kitchen was conducted by heating known amount of water by the technicians. Pre-weighed crop residue (500~700 g) was inserted into the stove burning chamber step by step (in 8~10 batches), following the way that rural residents usually do. The initial and final water temperatures were measured and listed in Table S2. Ash was collected and weighed after each burning experiment. Carbon content in ash was also analyzed in addition to that in primary fuel. The whole burning cycle lasted for 20 to 30 min with burning rates from 13 to 34 g/min depending on crop types (S2). In addition to the whole burning cycle, two burning phases of flaming and smoldering were tested individually. EFs were calculated using the carbon mass balance method (15). It was assumed that all the emitted carbon formed CO2, CO, total hydrocarbon species in gaseous phase and carbon in particulate phase. PAH EFs can then be calculated by multiplying CO2 EFs and the mass emission ratios of PAHs to CO2. The advantage of the carbon mass balance method is that it’s not necessary to collect all emitted species and the sampling site in the plume is adjustable (15).

Online detection and sampling were conducted in a mixing chamber equipped with a small fan to mix the exit emissions, and to avoid the influence of high temperature on sampling. There was no further dilution with clean gas as dilution ratios and rates might impact the mass load and size distributions of target compounds (6). CO2 and CO were measured using on-line non-dispersive infrared detectors (GXH-3051, Junfang Technical Institute of Physical and Chemistry, China). Relative humidity, smoke temperature, fire temperature, and burning duration were all recorded every 2 s. No significant difference in these recorded parameters (p>0.05, one sample K-S test) was found within all experiment cycles. The equipments were calibrated before each experiment using a span gas (CO: 1.00 % and CO2: 5.00 %). Before the burning, background concentrations were measured for correlation with emitted PAHs concentrations and EFs. For each crop residue, the combustion experiments were performed in duplicate, and a total of 17 tests were conducted (only one experiment for peanut residue due to lack of enough fuel).

Sample Collection

Gaseous and particulate phase PAHs were sampled using an active sampler (Jiangsu Eltong Electric Corp. Co., Ltd., China) at a flow rate of 1.5 l/min. The sampling media included quartz fiber filters (QFFs, 22 mm in diameter) followed by a polyurethane foam (PUF) plug (Supelco, 22 mm diameter×7.6cm) for particulate and gaseous phase PAHs, respectively. Size segregated samples were collected using a nine stage cascade impactor at a flow rate of 28.3 L/min with cutoff diameters of <0.4, 0.4~0.7, 0.7~1.1, 1.1~2.1, 2.1~3.3, 3.3~4.7, 4.7~5.8, 5.8~9.0, and 9.0~10.0 μm (FA-3, Kangjie, China). Before sampling, PUF were pre-extracted using acetone, followed by dichloromethane and then hexane. Each extraction lasted for 8 h. QFFs were baked at 450 ° C for 6 h before use. Both PUF and GFF were packed in aluminum foil and stored at −20 ° C prior to analysis.

Sample Extraction and Cleanup

Sample extraction and cleanup followed standardized internal procedures (S3) (16). Briefly, PUFs were Soxhlet extracted with 150 ml dichloromethane (DCM) for 8 h, concentrated to 1 ml using a rotary evaporator, re-dissolved into 3 mL hexane, and concentrated to 1 ml. Particulate loaded QFFs were extracted with 25 ml hexane/acetone mixture (1:1) using a microwave accelerated reaction system (CEM Corporation, Matthews, NC, USA). Microwave power was 1200 W and temperature was ramped to 110 ° C in 10 min and held at 110 ° C for another 10 min. The extract was concentrated to 1 ml and transferred to a silica/alumina column (12 cm silica gel, 12 cm alumina and 1 cm anhydrous sodium sulfate from bottom up, pre-eluted with 20 mL hexane) for cleanup. 70 ml hexane/DCM mixture (1:1) was used as elution solvent. The eluate was concentrated to 1 ml, conversed to hexane solution, and spiked with 250 ng internal standards (2-fluoro-1, 1’-biphenyl and p-terphenyl-d14, J&W Chemical Ltd., USA). All solvents were from Beijing Reagent, China and re-distillated and checked for PAHs blank before use. The silica gel and alumina were baked at 450 °C for 6 h, activated at 300 °C for 12 h, and deactivated with deionized water (3 %, w/w) prior to use. The anhydrous sodium sulfate was baked at 450 °C for 8 h. All glassware was cleaned in an ultrasonic cleaner and baked at 500 °C for at least 10 h.

Analysis

PAHs analysis was performed using a gas chromatograph (GC, Agilent 6890) connected to a mass spectrometer (MS, Agilent 5973). A HP-5MS capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm) was used. The oven temperature was programmed as 50 °C for 1 min, increased to 150 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min, to 240 °C at 3 °C/min, and then to 280 °C held for 20 min. Carrier gas was nitrogen. Data were collected in electron ionization (EI) mode and scanned from 35 to 500 mass units. Target PAHs were identified based on retention time and qualified ions of standards in selected ions mode (SIM). The following compounds were measured: naphthalene (NAP), acenaphthene (ACE), acenaphthyleme (ACY), fluorene (FLO), phenanthrene (PHE), anthracene (ANT), fluoranthene (FLA), pyrene (PYR), benzo(a)anthracene (BaA), chrysene (CHR), benzo(b)fluoranthene (BbF), benzo(k)fluoranthene (BkF), benzo(a)pyrene (BaP), dibenz(a,h)anthracene (DahA), indeno(l,2,3-cd)pyrene (IcdP), and benzo(g,h,i)perylene (BghiP).

Quality Assurance

Instrument detection limits were in a range of 0.13 ng (ACY) to 0.92 ng (BghiP). Method detection limits were from 0.23 ng/mL (NAP) to 1.42 ng/mL (BghiP) for gaseous PAHs and from 0.53 ng/mL (PHE) to 1.32 ng/mL (BghiP) for particulate PAHs. Recoveries of spiked standard PAHs ranged from 70 to 121% for gaseous, and 68 to 120% for particulate phase compounds (five duplicates). Deuterated PAHs (Nap-d8, Ant-d10, Ane-d10, Chr-d12, and Perylene-d12) were added as surrogates to monitor the extraction and cleanup procedures and surrogate recoveries were 75% ~ 127% for gaseous samples and 59% ~ 100% for particulate phase PAHs. The recoveries were acceptable and comparable to those reported for trace organic analysis in other studies (7, 13, 17–18). Procedure and reagent blanks were measured and subtracted from the results.

Results and Discussion

PAH Emission Factors

Total PAH EFs (wet basis) ranged from 27 mg/kg (cotton stalk) to 142 mg/kg (wheat straw), with overall mean EFs of 27 ± 13, 35 ± 23, and 62 ± 35 mg/kg for gaseous, particulate phase, and total PAHs. EFs of 16 individuals in both gaseous and particulate phases for different crop residues in whole burning cycle and two burning phases are presented in the S4 (Tables S3–S6). These results were higher than most data reported in literature (4–76 mg/kg) (7, 13, 19–21), primarily because the literature reported data were mostly based on chamber experiments. Compared with laboratory chambers, air flow is more limited, oxygen deficiency is more severe, and mixing is less complete in real cooking stoves, resulting in lower combustion efficiency and higher PAHs emissions (4). In addition, higher combustion temperature (measured as 550–750 °C in this study) due to limited heat loss in the stove is also favorable for PAHs formation (7, 22). It was reported that PAHs emissions increased dramatically when combustion temperature increased from 200 to 700 °C (7).

In the literature, it was also reported that the emissions of particulate matter (PM) and CO from incomplete combustion in the field were higher than those measured in laboratory (6, 8–10). It is important to understand the differences in EF PAHs between field studies and laboratory experiments and to obtain EF PAHs in the field, which are critical for developing a better emission inventory for exposure evaluation. In addition, since indoor solid fuel combustion is one of the main sources of PAHs in most developing countries (1), such information is also critical for assessing health effects of PAHs in indoor air of rural households.

EFs of total PAHs in the flaming and smoldering phases were 99 ± 60 and 58 ± 32 mg/kg, respectively. The nonparametric Wilcoxon test for paired samples and Spearman correlation analysis were applied using Statistica at a significant level of 0.05. Both gaseous and particulate phase EFs in the flaming phase were higher than those in the smoldering phase (p<0.05), similar to emission of PM and black carbon (11), which are often co-emitted with PAHs (22). One possible explanation for the higher emission in flaming phase is that combustion temperatures are more optimal for PAHs formation, while the lower temperature during smoldering leads to slower formation. Emission reductions due to low temperature in smoldering phase were also reported in an open-fire straw burning study (19).

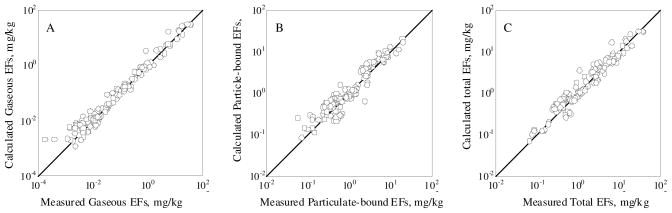

Measured PAH EFs for crop residues varied several orders of magnitude due to many factors including fuel moisture, combustion temperature, air supply, and fire management (5, 7, 13, 19–21). These factors often interact. For example, increased oxygen supply may promote PAH formation by increasing radical pool concentrations, but may also restrict PAH emission by enhancing oxidation (23). In this study, it was found that modified combustion efficiency (MCE, defined as CO2/(CO+CO2) ratios (molar basis)) was negatively correlated with EFs for total PAHs in gaseous and particulate phases (p=2.2 × 10−4 and p=2.4 × 10−4, respectively). Based on the results of a stepwise regression with a number of independent factors (C, H, N, moisture, and MCE) and EFs of 16 individual PAHs as dependent variables, it was found that moisture and MCE were the two most important factors affecting EFs of PAHs (p<0.05) (S5, Table S7). Calculated EFs of 16 PAHs based regression models using moisture and MCE as independent variables were plotted against the measured ones in Figure 1 and approximately 60 % of total variation can be explained. Lower emissions of total PAHs under higher combustion efficiencies of wheat straw burnt in field or laboratory chamber were also reported previously (13). The negative influence of moisture was likely because that high moisture can reduce burning temperature, increase PAH destruction rate, and also lead to lower PAH formation due to the decreased partial pressure of the reactants (7, 24). Prediction of EFs using the regression models would be helpful for identifying the key factors influencing EFs, and useful in better estimation of total emissions. Since it was found that MCE and moisture had significant effects on PAH EFs, and crop residues burned in this study were different types, it would be interesting to investigate the influence of different moisture of the same crop residue.

FIGURE 1.

Comparison between the measured and calculated EFs of gaseous (A), particulate-bound (B), and total (C) PAHs for crop residue burning. The calculation was based on a regression model with moisture and MCE as independent variables. The results are presented in log-scale.

As expected, it was found that EFs of both gaseous and particulate phase PAHs were significantly negatively correlated with CO2 EF and positively correlated with CO EF (p<0.05). EFs of particulate phase PAHs were also positively correlated with EFs for PM (p<0.05). Detailed results are in S5.

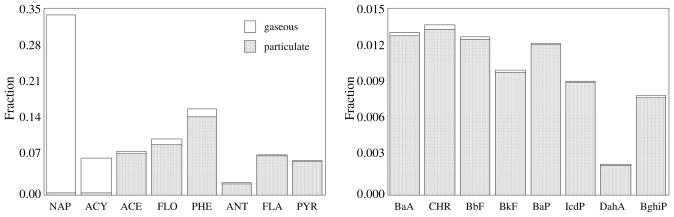

PAH Composition Profile

PAHs fractions for the whole burning cycle show 2–3 ring PAHs (from NAP to ANT) account for about 78% of total PAH emissions (Figure 2). NAP was the most abundant compound found in gaseous phase (76 ± 5 %), followed by ACY (15 ± 4 %). NAP domination in gaseous phase PAHs was also found from combustion of other crop residues and wood (7, 25). Particulate-bound PAHs found PHE (20 ± 12 %), FLA (11 ± 7 %), FLO (11 ± 7 %) and PYR (10 ± 7 %) to dominate. The profile was similar to that from wood and other combustion sources in general (26). There was no significant difference in the PAH profile between flaming and smoldering phases (p=0.121). Low molecular weight PAHs with 2–3 rings made up 80 ± 4 and 78 ± 7 % of the total in flaming and smoldering phases, respectively.

FIGURE 2.

Composition profile of PAH emission from crop residues burning in the cooking stove during a whole burning cycle. Both gaseous and particulate phase PAHs are shown as stacked bars.

Parent PAH isomer ratios are often used in receptor modeling for source apportionment by comparing PAH ratios between sources and receptors (27–28). Several commonly used isomer ratios includes ANT/(ANT+PHE), FLA/(FLA+PYR), BaA/(BaA+CHR), IcdP/(IcdP+BghiP), BbF/(BbF+BkF), and BaP/(BaP+BghiP). For example, it is suggested that the FlA/(FLA+PYR) being larger than 0.5 indicates from coal or biomass burning and petroleum combustion if it is smaller than 0.5 (28). Ratios derived in this study are compared with those reported in the literature (Table 1). Finding that, the measured ratios here are generally similar to those of crop residue burning in stoves (29–30) or chambers (4, 7, 13, 31), with a few exceptions, but are significantly different from those from open-field crop residue combustions (19–21). Significant differences in calculated ratios (except ANT/(ANT+PHE)) were found between crop residue burning (this study) and wood (25, 29, 32–33) or coal combustion (29, 34–35), although they are often classified into a same category of biomass. Large variations in PAH isomer ratios were also revealed for coals due to widely varying coal properties and combustion conditions. For example, IcdP/(IcdP+BghiP) values of 0.50~0.63 often were reported for residential coal chunks, but relatively low values (0.33~0.35) were found in briquette combustions (34–35). As such, these ratios should be used in caution since the ratios were not only fuel dependent, but also varied with burning conditions.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of parent PAH isomer ratios from this study and the literature reported values. The six ratios listed are often used for source apportionment. The results are shown as means and standard deviations.

| Ratio | Fuel | crop residue | crop residue | crop residue | crop residue | wood | coal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | stove | stove | chamber | open-fire | stove | stove | |

| Ref. | this study | 29–30 | 4, 7, 13, 31 | 19–21 | 25, 29, 32–33 | 29, 34–35 | |

| ANT/(ANT+PHE) | 0.12±0.01 | 0.2 | 0.18–0.25 | 0.17–0.25 | 0.10–0.30 | 0.13–0.58 | |

| FLA/(FLA+PYR) | 0.53±0.03 | 0.51–0.80 | 0.50–0.53 | 0.34–0.53 | 0.43–0.74 | 0.32–0.70 | |

| BaA/(BaA+CHR) | 0.48±0.02 | 0.46 | 0.46–0.53 | 0.39–0.50 | 0.39–0.56 | 0.27–0.56 | |

| IcdP/(IcdP+BghiP) | 0.54±0.02 | 0.31–0.50 | 0.46–0.52 | 0.39–0.94 | 0.16–0.69 | 0.23–0.63 | |

| BbF/(BbF+BkF) | 0.55±0.03 | 0.50–0.65 | 0.28–0.41 | 0.35–0.80 | 0.35–0.51 | 0.60–0.89 | |

| BaP/(BaP+BghiP) | 0.60±0.05 | 0.23–0.67 | 0.56–0.83 | 0.43–0.98 | 0.38–0.78 | 0.35–0.69 | |

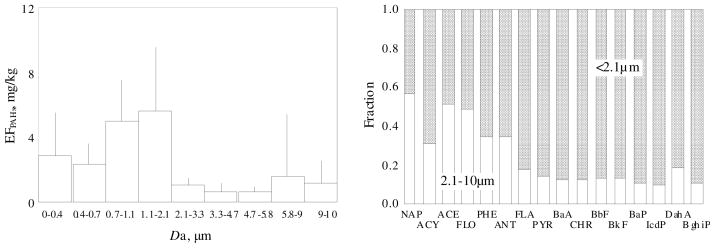

Size Distribution of Particulate Phase PAHs

For all crop residues tested, similar size distributions were observed with 54 ± 11 % of particulate-bound PAHs in the fraction between 0.7–2.1 μm (aerodynamic diameter) and over 80 ± 6 % were associated with PM2.5 (Figure 3, left panel), similar to other studies that find largest PAHs from fresh emissions are strongly associated with fine particles (36). The result is also similar to the measured distribution of particulate phase PAHs in ambient air in a mountain village (Donghe) in northern China where corn stalks are used widely for cooking and heating (16).

FIGURE 3.

Size distribution of particulate phase PAHs emitted from crop residue burning (left panel) and relative distribution of 16 individual PAH compounds between fine (<2.1 μm) and coarse (2.1–10 μm) particles (right panel). The means and standard derivations of EFs of PAHs associated with PM with different sizes from 17 burning experiments are shown.

Distribution of individual PAH compounds between fine (<2.1 μm) and coarse (2.1–10 μm) particles (Figure 3, right panel) suggests that the higher the molecular weight, the stronger the association with finer particles. Almost 60 % of NAP was associated with particles larger than 2.1 μm, while 81–90% of 4– to 6-ring PAHs from PYR to BghiP bound to particles with diameter less than 2.1 μm. This trend was also found in ambient air in a rural village of Donghe (16). Similar size distribution patterns were reported for particulate phase PAHs from rice residue burning and residential wood combustion (31, 37). The phenomenon has been explained by: 1) the difference in diffusivity that is correlated to molecular weight; 2) enhanced vapor pressures of lower molecular weight compounds have higher volatilization rates from small particles; and 3) more organic matter in larger particles may enhance absorption (37).

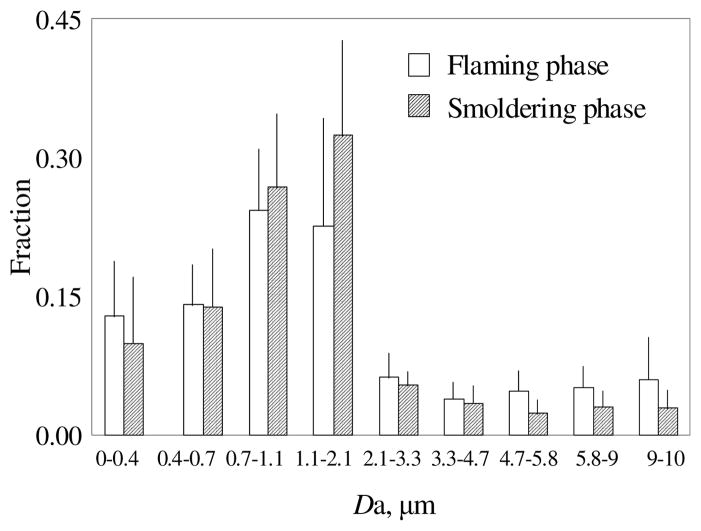

Similar to the whole burning cycle, both flaming and smoldering phases also showed unimodal distribution of particulate phase PAHs with the dominant size range of 0.7–2.1 μm (Figure 4). However, mass fractions of total PAHs in fine particles (<2.1μm) from flaming phase was 74 ± 9 %, which was significantly lower than that from smoldering phase (82 ± 7 %) (p=0.019). According to the measured results of PM emission from crop residue burning (14), particles emitted during the smoldering phase were smaller than those during the flaming phase and this is the main reason causing the difference in size distribution of particle-bound PAHs.

FIGURE 4.

Size distributions of particulate phase PAHs from flaming (blank column) and smoldering (filled column) phases of crop residues burning. Results shown are means and standard derivations of mass percents of each stages from all crop burning experiments (n=17).

Gas-particle Partitioning

Gas-particle partitioning of PAHs can be described by a partition coefficient (KP=F/(A × PM)), where F and A are concentrations in particulate (ng/m3) and gaseous phases (ng/m3), respectively and PM is particulate matter concentration (μg/m3) in air (38). The partition is believed to be governed by absorption and adsorption and the former is more relevant to organic carbon (OC) content, while the latter is often associated with surface area and black carbon (BC) content (39) , under influences of temperature, humidity, and radical concentration (39–41).

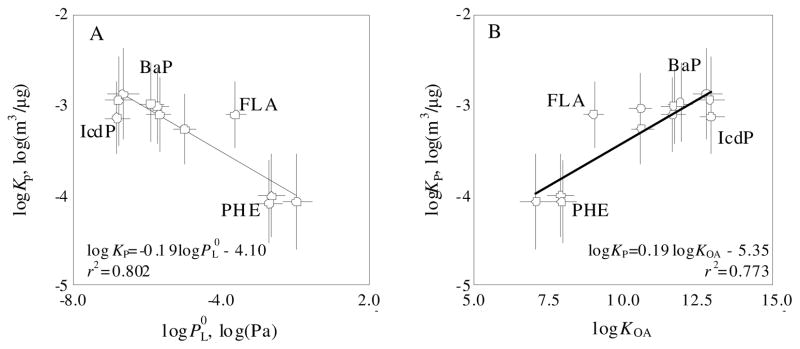

Figure 5 shows the relationship between KP and and between KP and KOA, where and KOA are subcooled liquid-vapor pressure and octanal-air partition coefficient of PAHs, respectively. The dependence of KP on the two parameters is well demonstrated. It is believed that the partition mechanism of PAHs can be characterized by the slope of the regression equation. A slope steeper than −1 suggests adsorption governance, while a slope shallower than −0.6 indicates absorption dominance (39). In this study, an extremely shallow slope of −0.19 (−0.23 ~ −0.15, 95 % confidence interval) was derived (Figure 5A), indicating that absorption rather than absorption dominated the partitioning in the exit flue of crop residue burning. Similar organic matter absorption of freshly emitted pollutants was found in wood combustion and diesel exhaust (6, 42). The absorption domination was also supported by significantly positive correlation (Figure 5B. p<0.05) between KP and KOA (41). Another piece of evidence supporting the absorption mechanism was that mass ratios of particle-bound PAHs were not particle size (Da) dependent (36, see S6). Also, the correlation between PAHs and OC (r=0.563, p=0.0093) was more significant than that between PAHs and BC (r=0.376, p=0.0685).

FIGURE 5.

Dependence of log(Kp) on (A) and log(KOA) (B). and KOA were calculated based on the measured temperatures and equations established by Odabasi et al., (43). PAH compounds of concern due to high abundance and/or toxicity, like PHE, FLA, BaP, and IcdP, are labeled. The means and standard derivations of measured Kp from 17 burning experiments are shown.

Discussion

The above discussion was based on the very limited experiments under given conditions in this study. Taking possible large variation in PAH EFs into consideration, the results can not be simply generalized and more studies on various fuel/stove combinations, effects of burning condition and cooking practices are needed in the future.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (40730737 and 140710019001), the National Basic Research Program (2007CB407301), the Ministry of Environmental Protection (200809101), and NIEHS (P42 ES016465). We thank Lisa Carlson for proof reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supporting Information available

The supporting materials are available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References Cited

- 1.Zhang Y, Tao S. Global atmospheric emission inventory of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) for 2004. Atmos Environ. 2009;43:812–819. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang Y, Tao S, Shen H, Ma J. Inhalation exposure to ambient polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and lung cancer risk of Chinese population. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:21063–21067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905756106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang J, Smith KR. Indoor air pollution: a global health concern. Br Med Bull. 2003;68:209–225. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldg029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang Y, Dou H, Chang B, Wei Z, Qiu W, Liu S, Liu W, Tao S. Emission of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons form indoor straw burning and emission inventory updating in China. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1140:218–227. doi: 10.1196/annals.1454.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gullett BK, Touati A, Hays MD. PCDD/F, PCD, HxCBz, PAH and PM emission factors for fireplace and woodstove combustion in the San Francisco Bay Region. Environ Sci Technol. 2003;37:1758–1765. doi: 10.1021/es026373c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roden CA, Bond TC, Conway S, Pinel ABO. Emission factors and real-time optical properties of particles emitted from traditional wood burning cookstoves. Environ Sci Technol. 2006;40:6750–6757. doi: 10.1021/es052080i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu H, Zhu L, Zhu N. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon emission from straw burning and the influence of combustion parameters. Atmos Environ. 2009;43:978–983. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson M, Edwards R, Alatorre Frenk C, Masera O. In-field greenhouse gas emissions from cookstoves in rural Mexican households. Atmos Environ. 2008;42:1206–1222. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roden CA, Bond TC, Conway S, Osorto Pinel AB, MacCarty N, Still D. Laboratory and field investigations of particulate and carbon monoxide emissions from traditional and improved cookstoves. Atmos Environ. 2009;43:1170–1181. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson M, Edwards R, Berrueta V, Masera O. New approaches to performance testing of improved cookstoves. Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44:368–374. doi: 10.1021/es9013294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bailis R, Berrueta V, Chengappa C, Dutta K, Edwards R, Masera O, Still D, Smith KR. Performance testing for monitoring improved biomass stove interventions: experiences of the household energy and health project. Energy for Sustainable Development. 2007;11:57–70. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bond TC, Streets DG, Yarber KF, Nelson SM, Woo J, Klimont Z. A technology-based global inventory of black and organic carbon emissions from combustion. J Geophys Res. 2004;109:D14203. doi: 10.1029/2003JD003697. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dhammapala R, Claiborn C, Simpson C, Jimenez J. Emission factor from wheat and Kentucky bluegrass stubble burning: comparison of field and simulated burn experiments. Atmos Environ. 2007;41:1512–1520. doi: 10.1021/es062039v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shen GF, Yang YF, Wang W, Tao S, Zhu C, Min Y, Xue M, Ding J, Wang B, Wang R, Shen H, Li W, Wang X, Russell AG. Emission factors of particulate matter and elemental carbon for crop residues and coals burned in typical household stoves in China. Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44:7157–7162. doi: 10.1021/es101313y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang J, Smith KR, Ma Y, Ye S, Jiang F, Qi W, Liu P, Khalil MAK, Rasmussen RA, Thorneloe SA. Greenhouse gases and other airborne pollutants from household stoves in China: a database for emission factors. Atmos Environ. 2000;34:4537–4549. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang W, Tao S, Wang W, Shen G, Zhao J, Lam K. Airborne particulates and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in ambient air in Donghe, Northern China. J Environ Sci Health Part A-Toxic/Hazard Subst Environ Eng. 2009;44:854–860. doi: 10.1080/10934520902958526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ding X, Wang X, Xie Z, Xiang C, Mai B, Sun L, Zheng M, Sheng G, Fu J, Pöschl U. Atmospheric polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons observed over the North Pacific Ocean and the Arctic area: Spatial distribution and source identification. Atmos Environ. 2007;41:2061–2072. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Su Y, Hung H. Inter-laboratory comparison study on measuring semi-volatile organic chemicals in standards and air samples. Environ Pollut. 2010;158:3365–3371. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2010.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hays MD, Fine PM, Geron CD, Kleeman MJ, Gullett BK. Open burning of agricultural biomass: Physical and chemical properties of particle-phase emissions. Atmos Environ. 2005;39:6747–6764. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jenkins BM, Jones AD, Turn SQ, Williams RB. Emission factors for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from biomass burning. Environ Sci Technol. 1996;30:2462–2469. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jenkins BM, Jones AD, Turn SQ, Williams RB. Particle concentrations, gas-particle partitioning, and species intercorrelations for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) emitted during biomass burning. Atmos Environ. 1996;30:3825–3835. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richter H, Howard JB. Formation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and their growth to soot-a review of chemical reaction pathways. Prog Energy Combust Sci. 2000;26:565–608. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ledesma EB, Kalish MA, Nelson PF, Wornat MJ, Mackie JC. Formation and fate of PAH during the pyrolysis and fuel-rich combustion of coal primary tar. Fuel. 2000;79:1801–1814. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Korenaga T, Liu X, Huang Z. The influence of moisture content on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons emission during rice straw burning. Chemosphere. 2001;3:117–122. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Conde FJ, Ayala JH, Afonso AM, Gonzalez V. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in smoke used to smoke cheese produced by the combustion of rock rose (Cistus monspeliensis) and tree heather (Erica arborea) wood. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:176–182. doi: 10.1021/jf0492013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khalili NR, Scheff PA, Holsen TM. PAH source fingerprints for coke ovens, diesel and gasoline engines, highway tunnels, and wood combustion emission. Atmos Environ. 1995;29:533–542. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watson JG. Overview of receptor model principles. J Air Pollut Contr Assoc. 1984;34:619–623. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yunker MB, Macdonald RW, Vingarzan R, Mitchell HR, Goyette D, Sylvestre S. PAHs in the Fraser River basin: a critical appraisal PAH ratios as indicators of PAH source and composition. Org Geochem. 2002;33:489–515. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oanh NTK, Albina DO, Ping L, Wang X. Emission of particulate matter and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from select cookstove-fuel systems in Asia. Biomass Bioenerg. 2005;28:579–590. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sheesley RJ, Schauer JJ, Chowdhury Z, Cass GR, Simoneit BRT. Characterization of organic aerosols emitted from the combustion of biomass indigenous to South Asia. J Geophys Res. 2003;108:D94285. doi: 10.1029/2002JD002981. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keshtkar H, Ashbaugh LL. Size distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon particulate emission factors form agricultural burning. Atmos Environ. 2007;41:2729–2739. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khalfi A, Trouvé G, Delobel R, Delfosse L. Correlation of CO and PAH emissions during laboratory-scale incineration of wood waste furnitures. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 2000;56:243–262. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hedberg E, Kristensson A, Ohlsson C, Johnsson P, Swietlicki E, Vesely V, Wideqvist U, Westerholm R. Chemical and physical characterization of emission from birch wood combustion in a wod stove. Atmos Environ. 2002;36:4823–4837. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen Y, Sheng G, Bi X, Feng Y, Mai B, Fu J. Emission factors for carbonaceous particles and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from residential coal combustion in China. Environ Sci Technol. 2005;39:1861–1867. doi: 10.1021/es0493650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Y, Schauer JJ, Zhang Y, Zeng L, Wei Y, Liu Y, Shao M. Characteristics of particulate carbon emissions from real-world Chinese coal combustion. Environ Sci Technol. 2008;42:5068–5073. doi: 10.1021/es7022576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Venkataraman C, Negi G, Sardar SB, Rastogi R. Size distributions of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in aerosol emission from biofuel combustion. J Aerosol Sci. 2002;33:503–518. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hays MD, Smith ND, Kinsey J, Dong Y, Kariher P. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon size distributions in aerosols from appliances of residential wood combustion as determined by direct thermal desorption-GC/MS. J Aerosol Sci. 2003;34:1061–1084. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pankow JF. Review and comparative analysis of the theories on partitioning between the gas and aerosol particulate phases in the atmosphere. Atmos Environ. 1987;21:2275–2283. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goss K, Schwarzenbach RP. Gas/solid and gas/liquid partitioning of organic compounds: critical evaluation of the interpretation of equilibrium constants. Environ Sci Technol. 1998;32:2025–2032. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kamens RM, Guo Z, Fulcher JN, Bell DA. Influence of humidity, sunlight, and temperature on the daytime decay of polyaromatic hydrocarbons on atmospheric soot particles. Environ Sci Technol. 1988;22:103–108. doi: 10.1021/es00166a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lohmann R, Lammel G. Adsorptive and absorptive contributions to the gas-particle partitioning of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: state of knowledge and recommended parametrization for modeling. Environ Sci Technol. 2004;38:3793–3803. doi: 10.1021/es035337q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spezzano P, Picini P, Cataldi D. Gas- and particle-phase distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in two-stroke, 50-cm3 moped emission. Atmos Environ. 2009;43:539–545. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Odabasi M, Cetin E, Sofuoglu A. Determination of octanol-air partition coefficients and supercooled liquid vapor pressures of PAHs as a function of temperature: application to gas-particle partitioning in an urban atmosphere. Atmos Environ. 2006;40:6615–6625. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.