Abstract

Background

The task of improving Social and Economic Determinants of Health (SEDH) imposes a significant challenge to health policy makers in both rich and poor countries. In recent years, while there has been increasing research interest and evidence on the workings of SEDHs, the vast majority of studies on this issue are from developed countries and emphasizes specific concerns of the developed nations of the world. Importantly, they may not fully explain the underlying causal factors and pathways of health inequality in the world's poorest countries.

Objective

To explore whether there are specific social determinants of health in the world's poorest countries, and if so, how they could be better identified and researched in Africa in order to promote and support the effort that is currently being made for realizing a better health for all.

Methods

Extensive literature review of existing papers on the social and economic determinants of health.

Conclusion

Most of the existing studies on the social and economic determinants of health studies may not well provide adequate explanation on the historical and contemporary realties of SEDHs in the world's poorest countries. As these factors vary from one country to another, it becomes necessary to understand country-specific conditions and design appropriate policies that take due cognisance of these country-specific circumstances. Therefore, to support the global effort to close gaps in health disparities, further research is needed in the world's poorest countries, especially on African social determinants of health

Keywords: social determinants of health, inequalities, policy priority, CSDH, Africa

Introduction

Most of the world's poorest countries are in Africa, and are required to minimize the huge inequalities in health that characterize their population groups. Socioeconomic caused inequalities in health are basically preventable, and could be considerably reduced through proper policy endeavor. Although only five years are left for achieving the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) of 2015, the degree of progress made so far by the majority of African countries is dismal. Millions of marginalized and deprived citizens living in poor African nations have failed to improve their achievements in health despite the commitments made by their governments to do so 1. Evidence obtained from various countries in Africa shows that the progress made so far on health care equity and population health targets is insufficient, and that most African countries are not on track to attain all the Millennium Development goals by the year 2015, including health targets2. To a considerable extent, improving SDHs has turned out to be a major challenge. The lack of progress has retarded the momentum towards promoting health equity and improving the health status of the poor in Africa.

Studies indicate that health inequalities which are caused by social and economic determinants of health are unfair and unnecessary because they are socially produced and can be ameliorated through meticulous policies that address socioeconomic inequalities3, 4. International interest in understanding the underlying drivers of differences in socioeconomic conditions and health status prompted the World Health Organization (WHO) to establish a Commission on the Social Determinants of Health (CSDH) in 2005. The Commission aimed to advance a health equity agenda and strengthen the organization's support to Member States in implementing a comprehensive approach to health problems5. The report produced by the CSDH and entitled “Closing the Gap in a Generation” offers a remarkable summary of evidence along with three broad policy recommendations that can be broken down into more than 50 policy measures4.

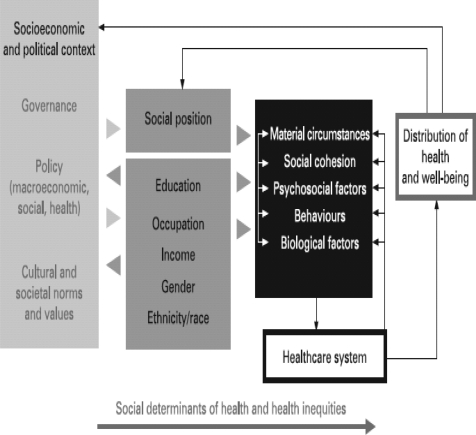

While the CSDH report raises a growing research interest on the social determinants of health, it is worth noting that most of the evidence that is currently available to the CSDH is provided by Western countries, and emphasizes specific concerns of the developed nations of the world (see Figure 1). Importantly, the list of factors identified by the CSDH as social determinants of health does not include the underlying causal factors and pathways of health inequality from the African perspective. As there are differences from country to country, reducing health inequalities may need country-specific contexts. Identifying causal factors at continental and country level is essential for prioritizing policy options, improving the delivery of basic health services, and the efficient utilization of scarce resources for tackling root causes of inequality.

Figure 1.

The commission on social determinants of Health's framework on the social determinants of health and health inequalities

Certainly global efforts for tackling social determinants of health and the dissemination of scientific knowledge regarding them are useful. But the assumption that the key determinants of health are the same everywhere is quite simplistic and questionable. First, given varying levels of economic development of different countries, causes of health inequalities vary depending on the level of economic development of a nation. The causes and extent of health inequality differ both within and between countries. Secondly, health inequality as a social phenomenon is both multi-faceted with multiple causes, which in turn requires multilevel research at local, national, continental and global levels. It is noteworthy, however that comparatively little research has been done in Africa to identify the appropriate social determinants of health and how these might best be tackled based on evidence-based and appropriate policy actions. Africanization of the SDH might therefore be useful to build on the work of the Commission in strengthening the global effort to achieve a better health for all in the worlds' poorest countries.

Methods

The study is based on extensive literature review of existing papers on the social and economic determinants of health. This includes WHO's Commission report on the Social Determinants of Heath. The review method draws more attention to explore four broad issues:

Are there particular social determinants of health in the world's poorest countries?

Are historical issues like colonization and its effects on clan segregation are important in explaining some of the causal pathways civil unrest and different health outcomes?

What policy areas should be given priority to reduce health inequalities? and

How should evidence-based research on social determinants from the perspective of African countries be conducted in order to understand the problem and for designing effective intervention policies?

Discussion

Africanization of social determinants of health

The key premise of this commentary is that, to support the global effort to close gaps in health disparities, further research is needed in the world's poorest countries, especially on African social determinants of health. Inequalities in health status between individuals and population groups exist in all economies where they are developed or developing. There is abundant evidence of the continued existence of racial differences in health elsewhere. For instance, research by6 reveals that African Americans and American Indians have higher age-specific death rates than whites from birth through retirement in the United States. Similarly, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare indicates indigenous Australians continue to live in conditions of enormous socioeconomic disadvantage and which is reflected in a life expectancy 17 years less than that of their non-Indigenous peers7. The UK's National Health Service (NHS) and Commission for Racial Equality indicates racial health disparities are a persistent problem with health care system and there is a need for tackling racial health gaps through race equity guide for achieving racial equality in the care of patients8. Undeniably racial inequity in health care is common to many pluralistic societies, and in recent years it is increasingly regarded as unacceptable because it is primarily caused by social structure which leads to more morbidity, medical complications, and mortality among the already disadvantaged population groups.

However, the factors that play the greatest role in producing health disparities may differ in different settings, and from one country to another9, 10. The Commission has fully recognized that identifying causality is crucial in order to understand the problem and to design an appropriate effective intervention strategy11. Although tackling health inequalities based on evidence on country-specific social determinants of health has shown to be helpful in reducing health disparities, major social determinants of health from Africa have often been ignored or oversimplified by the works of the WHO Commission on the SDH.

It is clear that health inequalities caused by poverty significantly differ from those caused by living in materially well-off but unequal societies. As such, solutions for improving health status and minimizing health disparity cannot be universally applied to all countries. As the causes of health inequality vary internationally, so do the solutions to the problems. Given the large proportion of the African population living below the international poverty line, and in view of the fact that the majority of the African population does not have the means to afford basic human needs, poverty may be the single dominating factor that is responsible for poor health in Africa12. Therefore, tackling poverty constitutes the greatest priority policy option in Africa. The CSDH offers three broad sets of recommendations that are suitable for closing the gap in health inequality in almost all countries. These are:

improving daily living and working conditions,

tackling unequal distribution of resources, and

measuring and understanding the problem to effectively tackling health disparities.

Underlying social stratifying factors

Health inequalities related to socioeconomic factors are mainly driven by variations in the distribution of the underlying social and economic determinants. Much is written in the literature on how socioeconomic status (SES) can be linked to households or individual's health status through living and working conditions1, 11. There is no mystery as to why people in poor working and living conditions suffer from high rates of morbidity and mortality. However, it seems that there is a knowledge gap about what constitutes the underlying causal factors in the world's poorest countries. This paper argues that differences in health status occur along several axes of social stratification factors and some of these factors might be more prominent to African countries although not unique to Africa13. It makes sense to consider poverty, health damaging cultural practices, colonial legacy and tribalism, armed conflicts, lack of good governance, poor macroeconomic policy, poor resources endowments, migration and global factors as major factors contributing for differences in the distribution of SDH and health inequality.

Tackling poverty seems to be the immediate concern in Africa for promoting better health for all. There is a question mark over the impact of current and potentially future inequality12. Poverty perpetuates ill-health through undernourishment, lack of clean water, poor sanitation and lack of access to basic and advanced health care services. These factors constitute immediate health risk factors for health, and have been reported as major causes of illness and mortality among poor people in Africa.

In contrast to what is known in poor African nations, in member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation for Development (OECD) illnesses caused by infectious diseases, malnutrition, low level of sanitation, lack of clean water or lack of access to health care facilities are not the cause for health inequality. In OECD countries, homicide, stress, depression, mental illness, alcoholism, drug abuse, anxiety, hopelessness and obesity are mainly caused by psychosocial effects which are more common in materially well-off, but unequal societies14. Societies with more unequal income distributions have poorer health outcomes than more egalitarian societies14, 16.

Africa is one of the continents which have been affected historically by colonialism. Colonial legacy in Africa manifests itself in the control of political power and ownership of the means of production and economic resources by a select few, tribal politics, lack of tolerance for differences in opinion, lack of respect for the basic rights of ordinary citizens, the abuse of power, corruption, lack of access to information. The divide-and-rule system which was used by the colonizers is still being used by the elites who are in power in many African nations. As a result, the quality of health depends on one's tribe, level of education, residential area, and other socioeconomic conditions14. Clans that were favoured by colonial masters have access to economic resources and political right, and refuse to share power and resources with other tribes. This results in an unequal share of national resources including the health system. In many African countries racial disparities can be associated with health differences, and can be used as a proxy for control of socioeconomic and political power.

The degree of armed conflict over resources and political power gain is most severe in many African nations. Armed conflict, internally or between countries, has a serious health damaging impact on poulation15. Widespread deaths of many innocent people, disability, displacement along with malnutrition, illnesses such as diarrhea, respiratory illness and AIDS, and breaking up of families are some of the consequences of armed conflicts. In addition to this, it distracts health care services, obstructs the individual's attempt to seek quality health care and improved treatment utilization19, 20. As such it limits the availability of economic resources for development activities such as health care services through diverting resources to support the conflict21, 22. Its long-term effect in degrading the living environment is quite negative on health. Various studies have shown that public health problems are quite severe in areas where there are armed conflicts22, 18.

Resource endowment such as fertile agricultural land, forest, fuel, minerals and good weather conditions offer greater opportunity for achieving better economic growth, human capital development and the wellbeing of the nation if properly managed23;13. Evidence shows that resource-rich countries perform well in terms of human and physical capital development as compared to resource-poor countries24. In many African countries, in spite of the presence of vast natural resources, relatively weak economic performance and poor human development have been noted25. Manufacturing industries and mining companies are not free from the health and safety risks of their workers, particularly at low levels of employments. As a result, work-related injuries, occupational hazards and illness, exposure to dangerous chemicals and pollutants, and deaths caused by preventable accidents compound the health challenge in Africa9.

The wellbeing of a nation largely depends, among other things, on the type of governance by which decisions and policy priority choices are implemented to manage public affairs. Governance includes the exercise of political, economic and administrative power to conduct public affairs and manage national resources. Good governance has far reaching positive social and economic impacts26, 27. In contrast, the abuse of power, corruption, nepotism, and wastage of limited public resources reduces government's capacity to provide good and quality services to the poor28. The nature of macroeconomic policy implemented in a nation is a measure of how fairly resources that are required for health are distributed among the general population. Lack of good governance, accountability coupled with corruption is one of the biggest challenges in health services delivery in the African continent13.

Harmful traditional and cultural practices are responsible for severe health related problems among the rural population in Africa. The impact has been most severe on poor rural mothers and their children. Female genital mutilation (FGM), food taboos for children and pregnant woman, widow inheritance, and use of traditional healings for instance, are well practiced cultural activities in many African countries. The health status of African women has been severely undermined by the promotion of harmful cultural activities which are not medical necessities. According to the UNFPA29 about 3 million women and girls face FGM every year without their consent. It is a persistent violation of the health rights of girls and women. Studies indicate that such a practice has both an immediate as well as long-term dire health consequences during pregnancy and child delivery30. Apart from FGM, the practice of widow inheritance is an important factor that reinforces health inequality on women. Widow inheritance hinders women from attaining a good standard of physical and mental health. In addition to this, the use of traditional medicine in Africa is widespread, and a sizeable proportion of illiterate and low income groups of people in Africa still depend on unregulated traditional healing as a form of medication.

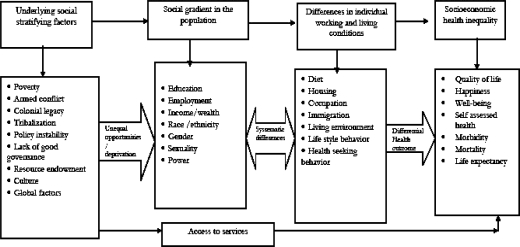

In addition to intra-African factors, there are other intra-continental issues that have an impact on the development of health in Africa. For instance, unfavorable trade agreements, asymmetric information on technological innovation, globalization and brain drain contribute for maintaining the current status-quo of poor health service delivery and low health status in most parts of Africa. This problem is more acute in Sub-Saharan African countries than anywhere else in the world. Yet, most of the above factors that play a significant role in exacerbating health inequalities are missed out in the literature on the social determinants of health. The findings of the CSDH do not reflect the broader underlying health inequality factors in the world's poorest countries such as Africa. This commentary argues that there is a need to research the African SDH to better tackle the root causes of health inequality, and for supporting and promoting the global effort for achieving a better health for all. Figure 2 below shows the link between the underlying social stratification factors, individual socioeconomic position indicators, health compromising factors and health inequalities from the African context. Some of the factors (such as the impact of colonization, armed conflicts, policy instability) introduced in the model are historical issues that are more specific to Africa though they are not unique to Africa.

Figure 2.

Conceptual model for tackling health inequalities under various socioeconomic and policy-related entry points

This model raises three important questions: First, are African countries sufficiently similar so that the Africanization framework is relevant and useful to most of the countries in Africa? Secondly, given that different countries could have varying social determinants of health, how could one overcome within-country differences? Would it be reasonable to propose social determinants of health for each region or district in the country? Thirdly, since our objective is to identify suitable country-specific policy options, how can such a model facilitate the choice and identification of the most suitable and feasible policy option for each country of interest?

We argue that, African countries, while they are by no means identical, they do share some common characteristics. These characteristics might also be more relevant to any of the world's poorest economies outside Africa. For instance, Paul Collier in his book, so-called “The Bottom Billion” indicates that many of development traps of developing countries are common13. These include the conflict trap (civil wars), the natural resources trap, being landlocked and having bad neighbors, and bad governance. Hence, identifying important social determinant factors and developing such a framework may be useful as a starting tool to any African country, and to increase awareness about the role played by social determinants of health that are relevant to the needs and challenges encountered by the worlds' poorest countries. Doing so enables policy makers to prioritize action plans for tackling the social and economic determinants of health objectively, and to utilize scarce resources efficiently. Africanization of the social determinants of health enables policy makers and planners to take a note of key factors that influence socioeconomic, cultural, political, and historical dimensions that are responsible for health inequality in most parts of Africa, and to better assist the design and implementation of problem-related policies.

The conceptual model shown above in Figure 2 explains the relationship between underlying social stratification factors and differential health outcomes. The continuous line represents causal effects to socioeconomic health inequality.

The social gradient

The social gradient is a measure of the social status of the individual in terms of level of education, level of skills, type of occupation, level of income or wealth, ownership of the means of production, possession of valuable assets, gender, and sexual orientation. As such, the socioeconomic status of the individual is a key indicator of the living and working conditions of the individual in the society. In most African countries, the poor are often characterized by poor access to health and education, low social standing, and high mortality and morbidity rates in comparison with the wealthy. Low level of income or lack of resources imposes constraints on the material conditions of everyday life by limiting access to fundamental health promoting activities such as personal hygiene, access to good nutrition, clothing, clean water, housing and the like. The task of improving health status in Africa is significantly dependent on socioeconomic, demographic, political and cultural factors. As such, addressing poverty-related challenges alone is not a guarantee for improving health inequality.

Policy-related entry points

To tackle socioeconomic health inequalities in Africa, helpful policy actions would be required in several domains. The lack of resources and reliable data poses a challenge to the task of designing policy interventions that could produce desired health and economic outcomes. African countries need to prioritize their developmental needs by placing emphasis to socioeconomic determinants of health rather than attempting to achieve all stated broad policy objectives recommended by the CSDH. The goals stated by the CSDH and their recommendations could be broken down into a list of more than 50 policy measures4. Prioritization of goals is essential for achieving the numerous targets and outcomes stated by the CSDH. Prioritization is also crucial for the efficient allocation of resources that are required for implementation. One should also bear in mind that implementation varies depending on level of development and nature of problem7.

Regrettably in many African countries the policy process of Africanizing the social determinants of health has so far been inefficient31. Although macroeconomic policies have the potential for protecting and improving the overall health status of the people in Africa, the policies in most parts of Africa have not been aligned to desirable health outcomes. Poverty, illiteracy, unemployment, income inequality, poor housing conditions, and migration are outcomes of inappropriate macroeconomic policies. Although the WHO has encouraged African governments to vigorously implement SDH policies, the number of health ministries and governments in Africa who have complied with the recommendation is quite few. The continent suffers from lack of good governance, tribalism, and armed conflicts. It must be noted that poor countries in various parts of the world have managed to improve the health status of their population by implementing helpful macroeconomic policy. Examples of such countries are Cuba, Costa Rica, the Kerala State of India32. In each of the above countries, a better health status has been achieved despite low level of economic development33.

The WHO Commission on the Social Determinants of Health has reported individual socioeconomic conditions as partially the root causes for much of health inequality. On the Global documentation much attention is given to the driving forces such as the social gradient, income inequality, early childhood life, occupation, stress, social exclusion, unemployment, level of social support, addiction to drugs and alcohol, and lack of access to food and transport. It is convenient, but quite wrong, to think that the social determinants of health are similar in developed and developing country. The causes, and therefore, the solutions differ in different settings and within and between different countries. This commentary argues that factors identified by the Commission do not include key socioeconomic factors that play a crucial role in affecting health outcomes in the world's poorest countries. Such factors do affect health inequality in most Sub-Saharan African countries, and should be added to the list of factors that need to be acted upon by the various African nations that hope to improve health inequality. Examples of factors that contribute for health inequality are abject poverty, tribalism, lack of good governance, the abuse of power, corruption, nepotism, harmful traditional culture, professional immigration, lack of technical skills, illiteracy, gender-related violence, armed conflict and colonial legacy. These factors individually or collectively affect the health inequality as well as widen the income gap. The majority of these factors affect a sizeable proportion of the world's poorest economies. Obviously, in countries where the majority of the population lives under the poverty line, the average population income gap will be quite high, the capacity of the state to address public issues will be rather weak, and benefits from economic growth to the poor will be minimal.

The social determinants of health can significantly differ from one country to another. This fact makes it difficult to accept the universality of social determinants of health, as is suggested by the CSDH. Rather than generalizing the social determinants of health globally, it is more realistic and practical to acknowledge that the factors that affect health inequality vary from country to country, as well as within countries. Factors that are relevant to poorly developed African nations should be defined and acted upon based on an African perspective. A suitable conceptual model along with a complex pathway on the social determinants of health in African countries has been proposed in this research article. Relevant social determinants of health should be identified for each African nation depending on specific characteristics that prevail in the nation. Doing so is quite essential for identifying differential health outcomes that could be used for setting public policy and implementation. It is quite helpful to initiate multi-disciplinary research on the Africanization of social determinants of health based on historical, social, cultural, economical and political perspectives that are more common to poor African nations.

Conclusion

More research work is required in order to better understand social and economic determinants of health in the African context, for prioritizing health needs, and for designing intervention strategies that could be used for reducing health inequality within and between African countries.

References

- 1.Commission on the Social Determinants of Health, author. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Easterly W. How the Millennium Development Goals are Unfair to Africa. World Development. 2009;37(1):26–35. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marmot M, Bell R. Health Equity and Development: the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Focus: Health in Europe. Cambridge University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH), author Discussion Paper for the Commission on Social Determinates of Health, Draft Paper on Conceptual Framework for Action on Social Determinants of Health. WHO publication; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kjellstrom T, Mercado S, Sami M, Havemann K, Wao S. Achieving Health Equity in Urban Settings. Journal of Urban Health. 2007;84:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s11524-007-9192-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams D, Sternthal M. Understanding Racial-ethnic Disparities in Health Sociological Contributions. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010;51:15–27. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare and Australian Bureau of Statistics, author. The health and welfare of Australia's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Canberra: ABS; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Health Service and Commission for Racial Equality, author. Race equality guide 2004: a performance framework. London: North Central London Strategic Health Authority; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garimoi CO. African Health Sciences. Health equity: challenges in low income countries. Vol. 9. Uganda: Makerere University; 2009. p. 2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelly M, Bonneefoy J, Morgan A, Florenzano F, Friel S, Houweling T, Bell R, Taylor S, Simpson S. Guide for the Knowledge Networks for the presentation of Reports and Evidence about the Social Determinants of health. Geneva: WHO/CSDH, Measurement and Evidence Knowledge Network (MEKN); 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Epstein D, Jimenez-Rubio, Smith P, Suhrcke M. Social Determinants of Health: An Economic Perspective. Health Econ. 2009;18:495–502. doi: 10.1002/hec.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Worku E, McIntyre D. Linking poverty and inequality to the health disparity: in the context of Millennium Development Goals of Africa; Paper presented on conference Health. Happiness. Inequality: Darmstadt, Germany Modelling the Pathways between Income Inequality and Health; 2010.2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collier P. The bottom billion: why the poorest countries are failing and what can be done about it. Oxford University Press: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilkinson R, Pickett K. Income Inequality and Social Dysfunction. Annu Rev Sociol. 2009;35:493–511. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marmot M, Wilkinson R, editors. Social Determinants of Health. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Subramanian S, Kawachi I. The Association between State Income inequality and worse health is not confounded by race. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2003;32:1022–1028. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyg245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Obadina T. The myth of Neo-colonialism. Africa Economic Analysis. 2000 viewed 6 September;, http://www.afbis.com/analysis/neo-colonialism.html. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berrang-Ford L. Civil conflict and sleeping sickness in Africa in general and Uganda in particular. Conflict and Health. 2007:1–6. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Victor W, Barry SL. Violence Prevention in Low and Middle Income Countries: Finding a Place on the Global Agenda, Workshop Summary. [23/03/2010]. Available at: http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=12016&page=171.

- 20.Ashford MW. The Impact of War on Women. In: Levy, Barry S, Sidel, Victor W, editors. War and Public Health. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. pp. 193–206. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoeffler A. Challenges of Infrastructure Rehabilitation and Reconstruction in Waraffected Economies. 1999. Background Paper for the African Development Bank Report. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gele AA, Bjune AG. Armed conflicts have an impact on the spread of tuberculosis: the case of the Somali Regional State of Ethiopia. [23/04/2010]. Available at: http://www.conflictandhealth.com/content/4/1/1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.African Development Bank, author. Does Natural Resources Endowment Matter in Africa. African Press Organization; [13/03/2010]. Available at: http://appablog.wordpress.com/2009/11/13/does-natural-resource-endowment-matter-in-africa/ [Google Scholar]

- 24.Graff Zivin J, Damon M. Health Shocks and Natural Resource Management: Evidence from Western Kenya. [12/04/2009]. Available at: http://www.aiid.org/docs/paper%20Maria%20Damon.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.United Nations University, author. The Global Financial Crisis and Africa's “Immiserizing Wealth”. http://www.merit.unu.edu/publications/pb/2010-01.pdf.

- 26.Marc H, Byong-Joon K, editors. Building Good Governance: Reforms in Seoul. National Center for Public Productivity; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barro R. Democracy and Growth. Journal of Economic Growth. 1996;1:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 28.United Nations Development Programme, author. Governance for sustainable human development, UNDP policy document. New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 29.UNFPA-UNICEF, author. Joint programme on Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting. Accelerating Change: Annual Report. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 30.United Nations Children's Fund, author. Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: A statistical exploration 2005. New York: UNICEF; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Resource Institute, author. Weak Governance, Institutional Capacity Slows MDG Progress in Sub-Saharan Africa. [06/06/09]. Available at: http://earthtrends.rri.org/updates/node/214. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sen AK. The possibility of social choice. American Economic Review. 1999:349–378. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mooney G, Fohtung N. Issues in the measurement of social determinants of health. Health Information Management Journal. 2008;37(3):26–32. doi: 10.1177/183335830803700304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]