Trypanosoma cruzi takes advantage of a sphingomyelinase-dependent plasma membrane repair pathway to gain access to host cells.

Abstract

Upon host cell contact, the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi triggers cytosolic Ca2+ transients that induce exocytosis of lysosomes, a process required for cell invasion. However, the exact mechanism by which lysosomal exocytosis mediates T. cruzi internalization remains unclear. We show that host cell entry by T. cruzi mimics a process of plasma membrane injury and repair that involves Ca2+-dependent exocytosis of lysosomes, delivery of acid sphingomyelinase (ASM) to the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane, and a rapid form of endocytosis that internalizes membrane lesions. Host cells incubated with T. cruzi trypomastigotes are transiently wounded, show increased levels of endocytosis, and become more susceptible to infection when injured with pore-forming toxins. Inhibition or depletion of lysosomal ASM, which blocks plasma membrane repair, markedly reduces the susceptibility of host cells to T. cruzi invasion. Notably, extracellular addition of sphingomyelinase stimulates host cell endocytosis, enhances T. cruzi invasion, and restores normal invasion levels in ASM-depleted cells. Ceramide, the product of sphingomyelin hydrolysis, is detected in newly formed parasitophorous vacuoles containing trypomastigotes but not in the few parasite-containing vacuoles formed in ASM-depleted cells. Thus, T. cruzi subverts the ASM-dependent ceramide-enriched endosomes that function in plasma membrane repair to infect host cells.

Trypanosoma cruzi, the intracellular protozoan which causes the seriously debilitating Chagas’ disease in Latin America, must invade cells to replicate within its vertebrate host. To gain access to the intracellular environment, several bacterial and protozoan pathogens rely on host cell actin polymerization, infecting mostly phagocytic cells (i.e., Leishmania; Moulder, 1985) or inducing macropinocytosis (i.e., Salmonella; Falkow et al., 1992). In contrast, the infective trypomastigote forms of T. cruzi invade a large number of different cell types by forming membrane-bound intracellular vacuoles independently of host cell actin rearrangements (Nogueira and Cohn, 1976; Schenkman et al., 1991; Tardieux et al., 1992). Earlier studies showed that host cell entry by T. cruzi involves the recruitment and fusion of host lysosomes at the parasite invasion site (Tardieux et al., 1992). Lysosomal markers are gradually detected in the nascent trypomastigote-containing intracellular vacuoles, suggesting that fusion of lysosomes provides the membrane required for parasitophorous vacuole formation (Tardieux et al., 1992). Subsequent studies demonstrated that trypomastigotes trigger intracellular free Ca2+ transients in host cells, which are required for lysosomal recruitment and fusion at the invasion site (Tardieux et al., 1994; Burleigh and Andrews, 1995; Rodríguez et al., 1995; Burleigh et al., 1997).

Studies of the T. cruzi invasion mechanism revealed that conventional lysosomes in mammalian cells can behave as Ca2+-regulated exocytic vesicles (Rodríguez et al., 1997) and led to the discovery that lysosomal exocytosis is involved in the mechanism by which eukaryotic cells repair wounds in their plasma membrane (Reddy et al., 2001). Initial observations established that wounded cells reseal their plasma membrane by a mechanism dependent on the influx of extracellular Ca2+ (Heilbrunn, 1956; Chambers and Chambers, 1961). The cellular mechanism responsible for plasma membrane repair began to be elucidated when a functional link was established between plasma membrane resealing and the exocytosis of intracellular vesicles (Bi et al., 1995; Miyake and McNeil, 1995). Peripheral lysosomes were subsequently identified as the major population of intracellular vesicles that respond to Ca2+ influx by fusing with the plasma membrane (Rodríguez et al., 1997; Jaiswal et al., 2002), promoting plasma membrane repair (Reddy et al., 2001).

Despite these advances, the mechanism by which Ca2+-triggered lysosomal exocytosis promoted the repair of lesions on the plasma membrane remained obscure. Reduction in plasma membrane tension after Ca2+-triggered exocytosis was proposed to play a role (Togo et al., 1999), as well as a direct patching of the wound by the Ca2+-responsive intracellular vesicles (McNeil et al., 2000). However, these models failed to explain how stable lesions, such as the ones caused by pore-forming toxins, were also rapidly removed from the plasma membrane in a Ca2+-dependent manner (Walev et al., 2001). Further investigation of this issue revealed that in addition to lysosomal exocytosis, Ca2+ influx triggers a rapid form of endocytosis that is required for the restoration of plasma membrane integrity (Idone et al., 2008).

A recent study showed that injury-dependent endocytosis is functionally linked to the secretion of a specific lysosomal enzyme, acid sphingomyelinase (ASM; Tam et al., 2010). ASM cleaves the phosphorylcholine head group of sphingomyelin, an abundant sphingolipid on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane (Koval and Pagano, 1991), generating ceramide (Gulbins and Kolesnick, 2003; Grassmé et al., 2007). Because ceramide has the property of coalescing in membranes forming domains capable of inward budding (Holopainen et al., 2000; Gulbins and Kolesnick, 2003; van Blitterswijk et al., 2003; Grassmé et al., 2007; Trajkovic et al., 2008), it was suggested that secretion of lysosomal ASM promotes plasma membrane repair through ceramide-driven internalization of lesions (Tam et al., 2010). Given the functional similarities between host cell invasion by T. cruzi and the resealing of membrane wounds, we investigated whether this parasite takes advantage of the cellular repair mechanism to gain access to the intracellular environment.

RESULTS

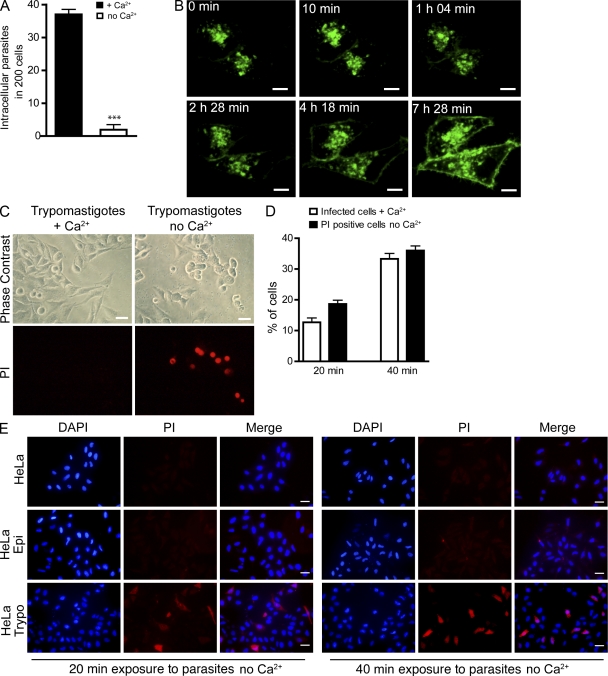

T. cruzi trypomastigotes wound host cells

As a first step in determining whether plasma membrane wounding and repair play a role in host cell invasion by T. cruzi, we performed invasion assays in the presence or absence of Ca2+ in the extracellular medium. HeLa cells incubated with infective trypomastigotes in the presence of Ca2+ (repair permissive condition) were readily infected. In contrast, without Ca2+ (condition nonpermissive for repair) very few invasion events were detected (Fig. 1 A). This was not a result of host cell loss because during the observation period similar numbers of host cells remained attached to the substrate in the presence or absence of Ca2+ (unpublished data). The requirement for extracellular Ca2+ in T. cruzi invasion is consistent with prior studies, which showed that host cell Ca2+ transients triggered by T. cruzi trypomastigotes are required for infection (Tardieux et al., 1994) and that Ca2+ signaling within trypomastigotes is also necessary for cell invasion (Moreno et al., 1994). To further document the involvement of host cell Ca2+-dependent signaling events in T. cruzi invasion, we imaged live HeLa cells expressing fluorescently tagged lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 (Lamp1) and exposed to trypomastigotes in the presence of Ca2+. As shown in Fig. 1 B and Video 1, over time the parasites induced massive translocation of the lysosomal membrane glycoprotein Lamp1 to the plasma membrane of host cells. These results show, for the first time in live cells, the Ca2+-dependent recruitment and exocytosis of host cell lysosomes that was previously documented in fixed cells (Tardieux et al., 1992).

Figure 1.

T. cruzi trypomastigotes wound mammalian cells and trigger the Ca2+-dependent plasma membrane repair response mediated by lysosomal exocytosis. (A) HeLa cells were incubated with trypomastigotes in the presence (membrane repair condition) or absence (nonrepair condition) of Ca2+ for 40 min, fixed, and stained for microscopic quantification of intracellular parasites. The data correspond to the mean of triplicates ± SD. ***, P < 0.0001, Student’s t test. (B) Time-lapse live images of cells transduced with Lamp1-RFP and incubated with trypomastigotes in the presence of Ca2+. The images show a single confocal plane of cells expressing Lamp1-RFP (green) during interaction with trypomastigotes. The first time point (0 min) was acquired after 20 min incubation of cells with 108 trypomastigotes. Bars, 10 µm. (Video1.) (C) Cell permeabilization and PI (red) influx in response to trypomastigotes in the absence (nonrepair condition) or presence (repair condition) of Ca2+. Live cells were imaged by phase contrast and epifluorescence 40 min after trypomastigote addition. Bars, 20 µm. (D) Quantification of the percentage of PI-positive cells (in Ca2+ free medium) in comparison with the percentage of cells infected with trypomastigotes (in Ca2+-containing medium). Trypomastigotes were allowed to invade cells for the indicated time periods and fixed coverslips were examined to determine the percentage of infected cells or PI-positive cells. Error bars show mean of triplicates ± SD. (E) Fixed cells after incubation with noninfective epimastigotes (Epi) or trypomastigotes (Trypo) in Ca2+-free medium in the presence of PI (red). Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Bars, 20 µm. These results are representative of three independent experiments.

Next, we investigated whether the exocytosis of lysosomes occurring during interaction of T. cruzi trypomastigotes with host cells involved cell wounding by the parasites. When HeLa cells were exposed to trypomastigotes in the presence of Ca2+ no staining was detected with the membrane-impermeable dye propidium iodide (PI), indicating that the plasma membrane remained intact (Fig. 1 C, left). However, after exposure to trypomastigotes in the absence of Ca2+, a condition which does not allow plasma membrane repair, several cells showed nuclear PI staining (Fig. 1 C, right). Given that plasma membrane resealing requires extracellular Ca2+ and is completed in less than 30 s (Steinhardt et al., 1994; Idone et al., 2008; Tam et al., 2010), these results suggest that T. cruzi trypomastigotes injure the plasma membrane of host cells but that when Ca2+ is present these wounds are rapidly resealed.

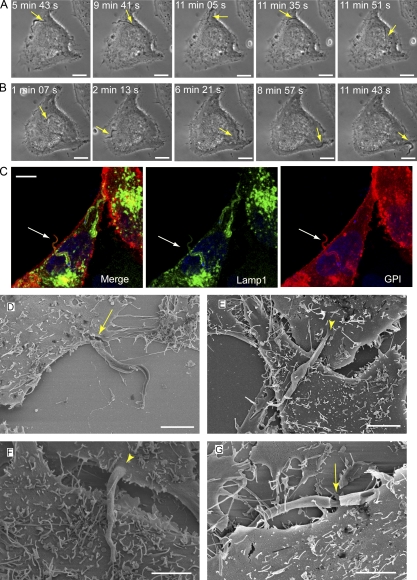

To compare the extent of host cell wounding (which can only be detected in the absence of Ca2+ because of the rapid repair) and host cell invasion (which only occurs in the presence of Ca2+), we performed parallel experiments with the same pool of host cells and parasites in the presence or absence of Ca2+. There was a close correlation between the percentage of infected cells over time under the repair-permissive conditions (with Ca2+) and the percentage of wounded cells detected under no-repair conditions (without Ca2+; Fig. 1 D). To determine if the ability to wound host cells was a specific property of the infective trypomastigote stages of T. cruzi, we performed similar assays using epimastigotes, the noninfective insect forms of T. cruzi, which are also flagellated and motile. Under Ca2+ depletion conditions, a markedly higher level of PI influx was detected in cells incubated with trypomastigotes, when compared with cells incubated for the same period of time with epimastigotes (Fig. 1 E and Fig. S1). This trypomastigote-specific wounding mechanism may be, at least in part, caused by Tc-Tox, the pore-forming protein secreted by T. cruzi trypomastigotes but not epimastigotes (Andrews and Whitlow, 1989; Andrews et al., 1990). However, secreted Tc-Tox permeabilizes cell membranes only at acidic pH and was implicated in the escape of trypomastigotes from their parasitophorous vacuole after invasion (Ley et al., 1990). Thus, it is likely that other factors, such as mechanical forces exerted on host cells by attached trypomastigotes may also play a role in plasma membrane wounding. In support of this possibility, imaging of the early interaction of trypomastigotes with HeLa cells revealed plasma membrane deformations caused by the active gliding motility of parasites firmly attached to host cells (Fig. 2 A and Video 2). Intriguingly, trypomastigotes become strongly attached and enter cells through their posterior end (Fig. 2, B and C), whereas their active flagellar motility propels them in the opposite direction (Hill, 2003). This unique situation, in which the parasite’s motility exerts forces on the plasma membrane which are opposed to their gradual movement into cells, may also be a source of plasma membrane injury.

Figure 2.

Interaction of T. cruzi trypomastigotes with host cells before invasion causes mechanical deformations on the plasma membrane. (A) Time-lapse phase-contrast live images of trypomastigotes interacting with a HeLa cell (Video 2). The gliding movement of attached trypomastigotes (arrow) cause reversible plasma membrane deformations (arrowhead). Bars, 10 µm. (B and C) Scanning electron microscopy images of trypomastigotes during early stages (10 min) of interaction with host cells. Trypomastigotes are observed gliding under cells (B) or in close contact with the plasma membrane at the cell periphery (C). Bars, 5 µm. These results are representative of two independent experiments.

Host cell injury with a bacterial pore-forming toxin promotes invasion by T. cruzi

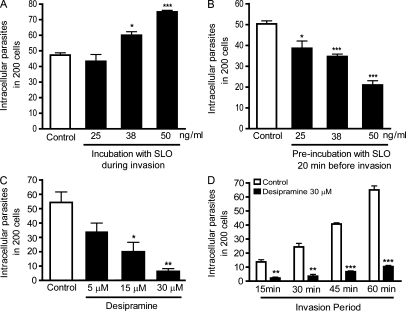

The findings discussed in the previous section suggested that injury inflicted in host cells by T. cruzi trypomastigotes is only detected in the absence of Ca2+ because the wounds are rapidly repaired in the presence of Ca2+. To determine whether wounding followed by repair influenced the cell invasion process, we added the pore-forming bacterial toxin Streptolysin O (SLO) to host cells during their incubation with the parasites. Permeabilization of HeLa cells by SLO was detected through PI influx under no repair conditions (without Ca2+; Fig. S2 A), whereas T. cruzi trypomastigotes remained intact (Fig. S2 B). This was expected because trypanosome membranes contain ergosterol but not cholesterol, which is essential for SLO pore formation (Tweten, 2005). Addition of SLO increased host cell invasion by T. cruzi trypomastigotes in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3 A). At 50 ng/ml SLO (a toxin concentration which allows Ca2+-dependent repair of the entire population of permeabilized cells; Idone et al., 2008; Tam et al., 2010) invasion was increased by ∼60% (Fig. 3 A). Interestingly, when cells were preincubated with SLO for 20 min before exposure to the parasites, T. cruzi invasion was reduced, also in a toxin dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3 B). These results suggest that the cellular machinery for plasma membrane wounding and repair is used by T. cruzi during host cell invasion and that host cell factors required for this process are depleted if the wounding and repair steps occur before exposure to the parasites.

Figure 3.

Host cell wounding and repair modulates T. cruzi invasion. (A) HeLa cells were exposed to trypomastigotes in the absence (white column) or presence (black columns) of increasing concentrations of SLO for 20 min, fixed, and processed for quantification of intracellular parasites. The data correspond to the mean of triplicates ± SD. *, P = 0.0149, Student’s t test comparing control and 38 ng/ml SLO-treated cells; ***, P < 0.0001, Student’s t test comparing control and 50 ng/ml SLO-treated cells. (B) Cells were pretreated for 20 min with increasing concentrations of SLO, washed, further incubated for 20 min, and exposed to trypomastigotes for 20 min followed by fixation and quantification of intracellular parasites. The data correspond to the mean of triplicates ± SD. *, P = 0.0182, Student’s t test comparing control and 25 ng/ml SLO-treated cells; ***, P < 0.0006, Student’s t test comparing control and 38 ng/ml or 50 ng/ml SLO-treated cells. (C) HeLa cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of the ASM inhibitor desipramine for 1 h, washed and exposed to trypomastigotes for 30 min, fixed, and processed for determination of the number of intracellular parasites. The data correspond to the mean of triplicates ± SD. *, P = 0.0125, Student’s t test; **, P = 0.0016, Student’s t test comparing control (white bars) and treated (black bars) bars. (D) Cells preincubated with 30 µM desipramine for 1 h were exposed to trypomastigotes for the indicated periods of time, washed, and processed for quantification of intracellular parasites. The data correspond to the mean of triplicates ± SD. **, P < 0.0014, Student’s t test; ***, P < 0.0001, Student’s t test comparing control (white bars) and treated (black bars) cells. These results are representative of four independent experiments.

Inhibition of lysosomal exocytosis and ASM activity block T. cruzi invasion

Recently, our laboratory demonstrated that bromoenol lactone (BEL; Fensome-Green et al., 2007) strongly inhibits lysosomal exocytosis and plasma membrane resealing after cell wounding (Tam et al., 2010). Treatment of HeLa cells with BEL also strongly inhibited invasion by T. cruzi trypomastigotes (Fig. S3, A and B), in agreement with prior studies which demonstrated a critical role for lysosomes in the T. cruzi invasion process (Tardieux et al., 1992; Andrade and Andrews, 2004). Next, we investigated whether the lysosomal enzyme ASM, which was previously shown to promote plasma membrane repair (Tam et al., 2010), was also required for T. cruzi invasion. HeLa cells were treated with the ASM inhibitor desipramine (Hurwitz et al., 1994; Kölzer et al., 2004) and analyzed for susceptibility to T. cruzi infection. A strong dose-dependent inhibition of trypomastigote entry was observed after desipramine treatment (Fig. 3, C and D), suggesting a role for secreted ASM in the T. cruzi invasion mechanism.

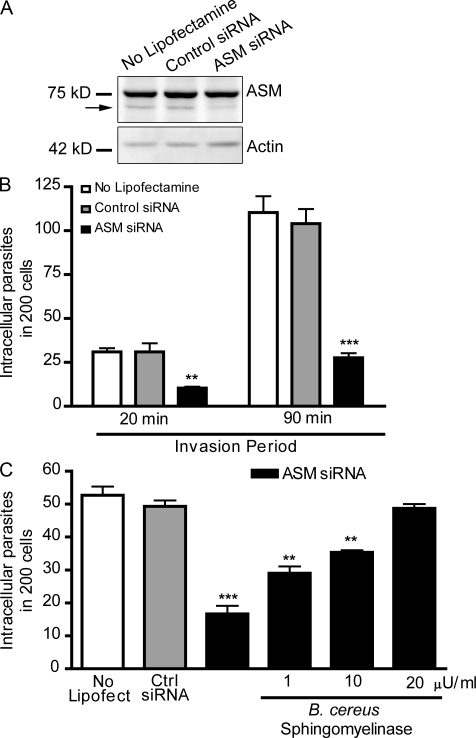

The inhibition in T. cruzi invasion observed after transcriptional silencing of ASM is reversed by extracellular addition of sphingomyelinase

To directly determine if trypomastigote entry requires ASM, we used small interfering (si) RNA to transcriptionally silence SMPD1, the gene encoding for ASM. A marked reduction in ASM expression was detected in HeLa cells treated with SMPD1 siRNA when compared with cells without lipofectamine or cells treated with control siRNA (Fig. 4 A). Under similar conditions, ASM activity in HeLa cells is reduced by ∼85% (Tam et al., 2010). As observed in desipramine-treated cells (Fig. 3, C and D), transcriptional silencing of ASM strongly reduced the susceptibility of host cells to invasion by T. cruzi (Fig. 4 B). Importantly, trypomastigote entry was restored to control levels by addition of Bacillus cereus sphingomyelinase during the infection period (Fig. 4 C). These results show that the role of lysosomal ASM in the T. cruzi invasion process can be bypassed by the extracellular addition of sphingomyelinase, suggesting that generation of ceramide in the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane by this enzyme directly promotes parasite entry.

Figure 4.

RNAi-mediated silencing of lysosomal ASM inhibits host cell invasion by T. cruzi, and exposure to extracellular sphingomyelinase restores parasite entry. (A) Immunoblot with anti-ASM antibodies in extracts of HeLa cells treated with control or ASM siRNA. The arrow points to the band corresponding to ASM; the higher additional band is an unspecific reaction. Immunoblot was probed with anti-actin antibodies for loading control. (B) Quantification of trypomastigote invasion in siRNA-treated HeLa cells. After siRNA treatment, cells were incubated with trypomastigotes for the indicated periods, fixed, and processed for quantification of intracellular parasites. The data correspond to the mean of triplicates ± SD. **, P = 0.0073, Student’s t test; ***, P < 0.0001, Student’s t test comparing control (gray bars) and ASM siRNA-treated cells (black bars). (C) siRNA-treated HeLa cells were incubated with trypomastigotes in the presence or absence of the indicated concentrations of bacterial sphingomyelinase for 30 min, fixed, and processed for quantification of intracellular parasites. The data correspond to the mean of triplicates ± SD. **, P < 0.0014; ***, P = 0.0003, Student’s t test comparing control (gray bars) and treated cells (black bars). These results are representative of four independent experiments.

To directly demonstrate the expected increase in ceramide levels promoted by exogenous addition of sphingomyelinase, nonpermeabilized HeLa cells pretreated with different concentrations of sphingomyelinase were incubated with anti-ceramide monoclonal antibodies and imaged (Fig. 5). The increase in plasma membrane immunofluorescence was proportional to the sphingomyelinase concentration, consistent with a role for newly generated ceramide in restoring T. cruzi invasion in ASM-depleted cells (Fig. 4 C). The Bacillus cereus sphingomyelinase used for these experiments is fully active at neutral pH, but earlier work demonstrated that extracellularly released lysosomal ASM also has sufficient extracellular activity for triggering plasma membrane repair (Tam et al., 2010) and signaling events that depend on ceramide generation in the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane (Schissel et al., 1998; Zha et al., 1998). Thus, our results suggest a role for secreted lysosomal ASM in the mechanism by which T. cruzi trypomastigotes invade host cells.

Figure 5.

Anti-ceramide monoclonal antibodies detect sphingomyelinase-induced increase in surface ceramide. Hela cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of Bacillus cereus sphingomyelinase for 30 min. After fixation with PFA, coverslips were labeled with 15B4 anti-ceramide monoclonal antibodies for 1 h followed by secondary antibodies. Ceramide labeling is shown in red. Bars, 20 µm. These results are representative of three independent experiments.

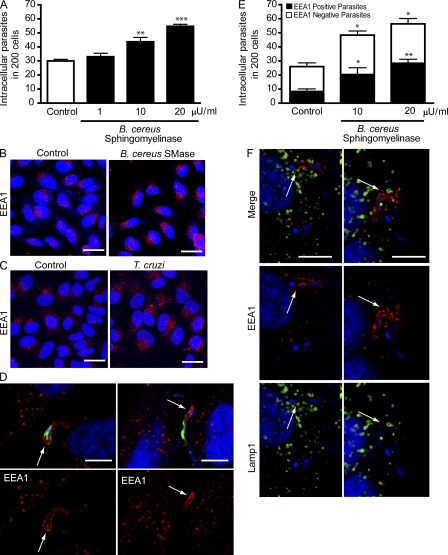

Sphingomyelinase stimulates endocytosis and promotes T. cruzi invasion

Exogenously added sphingomyelinase also increased the susceptibility to T. cruzi invasion of untreated HeLa cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6 A). Examination of the cells after exposure to sphingomyelinase revealed a marked increase in the number of early endosome antigen 1 (EEA1)–positive endocytic compartments (Fig. 6 B), similar to what was observed in cells permeabilized by SLO (Idone et al., 2008). An increase in EEA1-positive endosomes was also seen in HeLa cells exposed to T. cruzi trypomastigotes (Fig. 6 C). Confirming earlier results (Woolsey et al., 2003), a fraction of recently internalized T. cruzi trypomastigotes was detected within EEA1-enriched parasitophorous vacuoles (Fig. 6 D). Interestingly, the fraction of recently internalized trypomastigotes observed within parasitophorous vacuoles positive for EEA1 increased proportionally to the amount of exogenously added sphingomyelinase (Fig. 6 E). These observations support a role for lysosomal ASM, released during Ca2+-triggered exocytosis, in generating the EEA1-positive compartments where T. cruzi trypomastigotes reside shortly after entering cells. In agreement with this view, Lamp1-containing lysosomes were consistently observed in the vicinity of EEA1-positive vacuoles containing recently internalized parasites (Fig. 6 F).

Figure 6.

Exposure to T. cruzi trypomastigotes or to exogenous sphingomyelinase induces formation of EEA1-positive endosomes in host cells. (A) After exposure to trypomastigotes for 20 min, HeLa cells were fixed and processed for quantification of intracellular parasites. The data correspond to the mean of triplicates ± SD. **, P = 0.0078, Student’s t test comparing control (white bar) and 10 µU/ml sphingomyelinase–exposed cells (black bar); ***, P < 0.0001, Student’s t test comparing control and 20 µU/ml sphingomyelinase–treated cells. (B) EEA1-positive endosomes in HeLa cells incubated (SMase) or not (control) with 20 µU/ml sphingomyelinase for 20 min. DAPI DNA stain (blue), anti-EEA1 antibodies (red). Bars = 20 µm. (C) EEA1-positive endosomes in HeLa cells incubated (T. cruzi) or not (control) with trypomastigotes for 20 min. DAPI, blue; anti-EEA1 antibodies, red. Bars, 20 µm. (D) After 20 min of infection, HeLa cells were incubated with anti–T. cruzi antibodies (green) to stain extracellular parasites, followed by permeabilization and staining with anti-EEA1 (red). Arrows point to EEA1 staining associated with the intracellular region of partially internalized parasites. DAPI (blue). Bars, 10 µm. (E) Quantification of the number of intracellular trypomastigotes in EEA1 positive vacuoles 20 min after invasion in the presence of sphingomyelinase. After infection, cells were incubated with anti–T. cruzi antibodies to stain extracellular parasites, followed by permeabilization and staining with anti-EEA1. The data correspond to the mean of triplicates ± SD. *, P < 0.04, Student’s t test; **, P = 0.002, Student’s t test, comparing control and treated cells. (F) After 20 min of infection, HeLa cells were fixed, permeabilized and stained with anti-EEA1 (red) and anti-Lamp1 (green) antibodies. DAPI, blue. Arrows indicate intracellular parasites within EEA1-enriched parasitophorous vacuoles and closely associated with Lamp1-containing lysosomes. Bars, 10 µm. These results are representative of three independent experiments.

ASM secretion promotes T. cruzi internalization through ceramide-enriched compartments

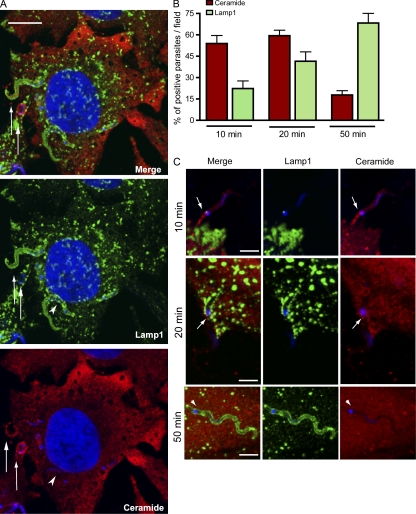

Collectively with the earlier demonstration that exocytosis of lysosomal ASM promotes plasma membrane repair (Tam et al., 2010), the results described in the previous section support the hypothesis that T. cruzi subverts the plasma membrane injury and repair pathway for invading host cells. The role of sphingomyelinase in promoting T. cruzi invasion suggests that ceramide generation in the plasma membrane contributes to the formation of the early parasitophorous vacuole in a manner analogous to the internalization of membrane lesions during cell resealing (Idone et al., 2008). To test this hypothesis, we used anti-ceramide monoclonal antibodies to localize areas of ceramide accumulation in HeLa cells recently infected with T. cruzi. As shown in Fig. 5, surface staining with this antibody increased markedly after HeLa cells were treated with Bacillus cereus sphingomyelinase, confirming its specificity for ceramide. Isotype control antibodies did not stain HeLa cells or T. cruzi trypomastigotes (Fig. S4, A and B). Although T. cruzi also contains free ceramide, biochemical analysis showed that trypomastigotes contain lower amounts when compared with the intracellular replicative stages, amastigotes (Bertello et al., 1996). In agreement with these findings, T. cruzi amastigotes stained strongly with the anti-ceramide monoclonal antibodies (unpublished data), whereas trypomastigotes showed a weak staining, which was further reduced after extraction of the fixed parasites with 0.2% Triton X-100 (Fig. S5 B). In contrast, anti-ceramide antibodies still strongly reacted with ceramide present in HeLa cells permeabilized with 0.1 or 0.2% Triton X-100 (Fig. S5 A). Having established conditions to reduce detection of trypomastigote endogenous ceramide, we proceeded to examine the distribution of host cell ceramide in HeLa cells recently infected with T. cruzi. Although ceramide-enriched parasitophorous vacuoles containing T. cruzi trypomastigotes could be detected, the abundant cytoplasmic staining for ceramide in host cells made quantification difficult. Unexpectedly, we observed that the highly motile recently internalized trypomastigotes often caused a marked deformation of the plasma membrane, protruding from the host cell with their anterior end oriented toward the outside (Video 3; Video 4; and Fig. 7, A and B). Although protruding, trypomastigotes were surrounded by two membranes, one corresponding to the parasitophorous vacuole formed during invasion and another derived from the deformed plasma membrane. This topology was evident in immunofluorescence images, showing that the protruding parasite portion was surrounded by Lamp1 (delivered through lysosomal fusion with the parasitophorous vacuole) and a plasma membrane marker, YFP–glycosyl phosphatidylinositol (GPI; Fig. 7 C). Scanning electron micrographs confirmed that the membrane enveloping the long protrusions was continuous with the plasma membrane (Fig. 7, D–F), and occasional breaches in these electron microscopy preparations revealed the presence of trypomastigotes inside the plasma membrane–derived sleeves (Fig. 7 G). This phenomenon provided an excellent opportunity to examine recently formed parasitophorous vacuoles for the presence of ceramide, away from the abundant ceramide present in the host cell cytosol. Using laser-scanning confocal fluorescence microscopy, parasitophorous vacuoles were imaged at various time points after parasite invasion after staining with anti-ceramide monoclonal antibodies. At 15 min after infection, imaging of cells overexpressing fluorescently tagged Lamp1 showed that protruding parasites often appeared to be surrounded by a punctate staining with the anti-ceramide antibodies (Fig. 8 A, arrows), whereas only a fraction of the parasitophorous vacuoles contained Lamp1 (Fig. 8, B and C). After increasing periods of infection, ceramide enrichment in the parasitophorous vacuoles decreased, whereas Lamp1 increased (Fig. 8 B), suggesting a process in which ceramide is gradually metabolized/removed while lysosomes continue to fuse with the parasitophorous vacuole. Lysosomes were frequently detected in close association with the ceramide-enriched parasitophorous vacuoles (Fig. 8 C), consistent with early lysosomal fusion events being responsible for ASM release, and ceramide generation at the site of parasite invasion.

Figure 7.

Recently internalized parasites are highly motile and protrude from host cells. (A) Time lapse of T. cruzi internalization and intracellular movement in a HeLa cell (Video 3). The arrow indicates the invading trypomastigote. Bars, 10 µm. (B) Time-lapse images of the same cell in A (initiated ∼15 min after the last frame of the previous video), showing that the trypomastigote remains highly motile and then protrudes from the host cell. The arrow indicates the intracellular trypomastigote. Bars, 10 µm. (C) Confocal images of a trypomastigote protruding from the host cell surface 30 min after invasion of a HeLa cell transduced with the plasma membrane marker GPI-YFP (red) and Lamp1-RFP (green). After infection, cells were fixed and DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). The arrow indicates an internalized parasite already within a Lamp1-positive compartment, protruding from the GPI-labeled host cell plasma membrane. Bar, 10 µm. (D–G) Scanning EM images of protruding trypomastigotes. HeLa cells exposed to trypomastigotes for 20 min were washed and incubated for an additional 15 min before fixation and processing for scanning electron microscopy. Bars, 5 µm. Arrowheads indicate the continuity between the plasma membrane and the protrusion, and arrows indicate sites where the plasma membrane was fractured, revealing the parasitophorous vacuole membrane. These results are representative of two independent experiments.

Figure 8.

Vacuoles containing recently internalized parasites are enriched in ceramide while gradually acquiring Lamp1. (A) Single optical section of a HeLa cell expressing Lamp1-RFP (green) infected with trypomastigotes for 15 min, fixed, permeabilized, and stained with anti-ceramide antibodies (red). Trypomastigotes (arrows) can be observed in vacuoles enriched in ceramide (red), of which one has already fused with Lamp1-RFP–containing lysosomes (green). The arrowhead indicates a Lamp1-positive parasite vacuole that is negative for ceramide. Bar, 10 µm. (B) Quantification of intracellular parasites found in ceramide or Lamp1-enriched vacuoles over time. After 10 or 20 min of exposure to trypomastigotes, cells were washed and either fixed or incubated for an additional 30 min before fixation (50-min time point). Cells were then permeabilized, stained with antibodies to ceramide (red) or Lamp1 (green), and confocal Z series were obtained in 15 fields for each condition, followed by quantification of parasites associated with ceramide and Lamp1. The data represents mean ± SD of the percentage of positive parasites per field (n = 15). (C) Representative images (single optical sections) of each time point in B. At 10 and 20 min, protruding parasites were often observed in ceramide-enriched vacuoles (arrows). Ceramide, red; Lamp1, green; DAPI, blue. The arrowheads indicate a Lamp1-positive parasite vacuole that is negative for ceramide. Bars, 5 µm. These results are representative of three independent experiments.

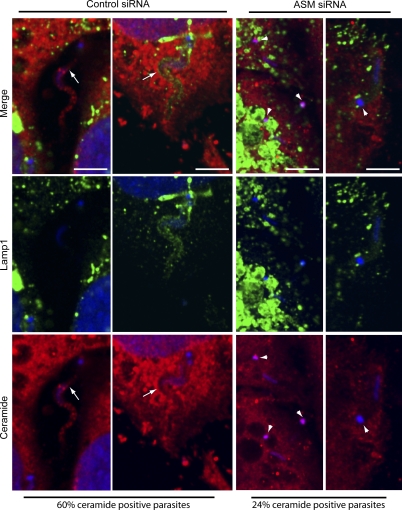

To directly establish a link between ceramide enrichment in parasitophorous vacuoles and the release of ASM from lysosomes, we imaged cells treated with control or SMPD1 siRNA. As shown in Fig. 4, the siRNA treatment conditions we used reduced the ASM content of HeLa cells in ∼85% and caused a similar inhibition in trypomastigote invasion. The residual parasite invasion still observed in ASM-depleted cells allowed us to compare the levels of staining with anti-ceramide antibodies in cells depleted or not of ASM. After 20 min of infection, 60% of the intracellular trypomastigotes observed in cells treated with control siRNA were detected in ceramide-enriched parasitophorous vacuoles, whereas in ASM-depleted cells only 24% of the parasite-containing vacuoles stained with the antibodies. In both groups of cells, treated with control or ASM siRNA, lysosomes were observed in close association with recently internalized parasites (Fig. 9). Collectively, these results establish a link between T. cruzi–induced plasma membrane injury, Ca2+-dependent exocytosis of lysosomes, ASM secretion, and the generation of ceramide-enriched endocytic compartments, which facilitate parasite internalization.

Figure 9.

Ceramide-enriched T. cruzi-containing vacuoles are dependent on ASM activity. HeLa cells treated with control or ASM siRNA were exposed to trypomastigotes for 20 min, fixed, and processed as described in Fig. 7. Confocal Z series analysis performed in 15 fields for each condition revealed a smaller percentage of ceramide positive vacuoles in cells treated with ASM siRNA (24%) when compared with control siRNA (60%). Representative images of single optical planes for each condition are shown (two examples of control siRNA and two examples of ASM-siRNA). Ceramide, red; Lamp1, green; DAPI, blue. The arrows indicate parasites within vacuoles positive for ceramide staining in cells treated with the control siRNA. Arrowheads point to the DAPI-stained kinetoplasts of trypomastigotes within vacuoles negative for ceramide staining, in cells treated with ASM siRNA. Bars, 5 µm. These results are representative of three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

The mechanism by which T. cruzi trypomastigotes invade host cells depends on their ability to trigger intracellular free Ca2+ transients in host cells (Burleigh et al., 1997; Burleigh and Andrews, 1998; Burleigh and Woolsey, 2002; Yoshida and Cortez, 2008). T. cruzi-induced Ca2+ signaling triggers the recruitment and fusion of host lysosomes with the plasma membrane at the site of parasite entry, and it triggers parasitophorous vacuole formation (Tardieux et al., 1992, 1994). A similar process of Ca2+-dependent exocytosis of lysosomes is observed during the process of plasma membrane injury and repair (Reddy et al., 2001). Plasma membrane wounding, lysosomal exocytosis, and a rapid form of endocytosis that follows cell injury were all shown to be functionally linked and dependent on secretion of the lysosomal enzyme ASM (Idone et al., 2008; Tam et al., 2010). These findings led us to hypothesize that membrane damage and extracellular Ca2+ influx might also represent an early step in the interaction of T. cruzi trypomastigotes with host cells and that the steps of lysosomal exocytosis and endocytosis involved in the plasma membrane repair process are subverted by the parasites for invasion. In this study, we provide several lines of evidence in support of this view. First, host cell wounding was detected in cells exposed to infective trypomastigotes, but not to noninfective epimastigotes, when plasma membrane repair was blocked by removing Ca2+ from the extracellular medium. Second, injuring host cells with SLO during interaction with trypomastigotes enhanced infection. Third, blocking lysosomal exocytosis or release of the lysosomal enzyme ASM, interventions which inhibit plasma membrane repair (Reddy et al., 2001; Tam et al., 2010), markedly reduced the susceptibility of host cells to T. cruzi invasion. Importantly, addition of purified sphingomyelinase restored parasite invasion in cells depleted of ASM, directly linking sphingomyelin hydrolysis and ceramide generation to the T. cruzi entry process. Fourth, ceramide accumulation was detected in recently formed parasitophorous vacuoles, suggesting that this lipid plays an important role in the plasma membrane deformation process that is required to allow the large trypomastigotes (10–15 µm long) to enter host cells. These results significantly expand the previously reported role of lysosomal exocytosis in host cell invasion by T. cruzi (Tardieux et al., 1992; Andrade and Andrews, 2004) by showing that a lysosomal enzyme released extracellularly can promote parasite internalization.

Before this study, T. cruzi–induced membrane damage had only been detected after host cell invasion, during the process of disruption of the parasitophorous vacuole which allows the parasites to escape to replicate in the cytosol (Ley et al., 1990). Our current results show that the infective trypomastigote forms of T. cruzi, but not the noninfective epimastigotes, can also wound the plasma membrane of host cells. The capacity of trypomastigotes to injure host cells may be a result of the residual activity of Tc-Tox, the acid-active pore-forming protein secreted by the infective stages of T. cruzi (Andrews and Whitlow, 1989; Andrews et al., 1990), and/or to the active motility of trypomastigotes when attached to host cells (Video 2 and Fig. 2).

We found that interaction with T. cruzi trypomastigotes stimulates formation of EEA1-positive endocytic vesicles in host cells, similar to what is observed in cells exposed to purified sphingomyelinase (Zha et al., 1998; Tam et al., 2010). ASM cleaves the head group of the abundant plasma membrane lipid sphingomyelin, generating ceramide in the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane (Schissel et al., 1998). Ceramide-enriched membrane microdomains have the property of coalescing and budding inwards (Holopainen et al., 2000; Gulbins and Kolesnick, 2003; van Blitterswijk et al., 2003; Trajkovic et al., 2008), providing a mechanism for endosome formation (Tam et al., 2010). EEA1 and ceramide were also found to accumulate in the trypomastigote-containing recently formed parasitophorous vacuoles, strongly suggesting that T. cruzi subverts this ASM-dependent Ca2+-triggered endocytic process to form its intracellular compartment. Consistent with this scenario, cells treated with the cholesterol-sequestering agent MβCD (methyl-β-cyclodextrin) show a significant reduction in the number of Ca2+-dependent endosomes formed after injury and fail to efficiently repair their plasma membrane after wounding. This finding is similar to what is observed for the T. cruzi invasion process, which involves sphingolipid and cholesterol-enriched lipid rafts and is inhibited by cholesterol depletion (Fernandes et al., 2007).

Trypanosomes move unidirectionally, with their anterior end oriented forward (Hill, 2003). Intriguingly, T. cruzi trypomastigotes attach and invade host cells by their posterior end, where the base of the flagellum is located. This implies that the driving force for parasitophorous vacuole formation must be provided by the host cell, because the parasite is hauled into the intracellular environment despite its own motility, which propels it in the opposite direction. T. cruzi invasion is independent of host cell actin polymerization (Schenkman and Mortara, 1992; Tardieux et al., 1992) but requires intact microtubules (Tardieux et al., 1992). These findings emphasize a role for the gradual fusion of lysosomes with the parasitophorous vacuole as a mechanism for the strong association of nascent parasitophorous vacuoles with microtubules, resulting in an internalization and intracellular retention process dependent on microtubule motors (Tardieux et al., 1992; Andrade and Andrews, 2004). The model we propose in this study introduces an important additional element in the T. cruzi invasion mechanism. Our model suggests that secretion of host lysosomal hydrolases, followed by lipid remodeling at the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane, plays a major role in the initial formation of T. cruzi–containing intracellular vacuole. Important steps of this process that still remain to be clarified include the nature of the strong attachment that occurs between the posterior end of trypomastigotes and the host cell surface and how the nascent parasitophorous vacuole pinches off from the plasma membrane.

Unexpectedly, when imaging trypomastigotes shortly after host cell invasion, we observed that their active motility often led them to collide with the plasma membrane and protrude from the cell with their anterior end pointing outwards (Video 4 and Fig. 7 B). Scanning electron micrographs revealed fully internalized trypomastigotes surrounded by a tight membrane layer that was continuous with the plasma membrane and that stretched outwards for the full length of the parasite. In some cases, these protruding trypomastigotes also showed the presence of Lamp1 in their parasitophorous vacuole, in agreement with the early fusion of lysosomes observed during the T. cruzi entry process (Tardieux et al., 1992). This protrusion phenomenon facilitated the detection of ceramide enrichment in parasitophorous vacuoles surrounding recently internalized trypomastigotes by allowing imaging at sites separated from the ceramide-rich intracellular environment. The frequency by which trypomastigotes protrude and stretch the host cell membrane from the inside after invasion suggests that this could be another form of parasite-induced wounding. Rupture of the plasma membrane extensions created during this process would allow Ca2+ entry, activating plasma membrane repair and increasing host cell susceptibility to additional invasion events. Interestingly, this scenario may explain why T. cruzi infection of mammalian cells does not follow a random Poisson distribution but corresponds more closely to a negative binomial prediction (Hyde and Dvorak, 1973). Wounding by protruding trypomastigotes may make host cells more susceptible to additional invasion events by triggering plasma membrane repair. These protruding events also offer an alternative explanation to earlier results of trypomastigotes that appeared to be enveloped by plasma membrane markers, after short periods of interaction with host cells (Woolsey et al., 2003).

The demonstration that ASM induces formation of ceramide-enriched endocytic vesicles that can facilitate trypomastigote entry significantly advances our understanding of the molecular mechanism that renders lysosomes essential players during the invasion of host cells by T. cruzi. Our results indicate that, by wounding host cells, T. cruzi trypomastigotes trigger plasma membrane repair, lysosomal exocytosis, ASM release, and formation of ceramide-enriched endosomes that facilitate parasite entry. Importantly, our findings also suggest that the tissue tropism exhibited by T. cruzi within its vertebrate host, with the strong preference of the parasites to invade cardiomyocytes and smooth muscle, may be related to the frequency by which these cell types are injured in vivo (McNeil and Steinhardt, 2003).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Host cells and parasites.

HeLa cells CCL-2.1 (American Type Culture Collection) were grown in DME (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10% FBS at 37°C with 5% CO2. Trypomastigotes from the Trypanosoma cruzi Y strain were obtained from the supernatant of infected monolayers of LLC-MK2 cells, as previously described (Andrews et al., 1987). Epimastigotes from T. cruzi Y strain were cultured in liver infusion tryptose medium containing 10% FBS at 28°C (Nogueira and Cohn, 1976).

Invasion assays and quantification of parasite invasion.

1.8 × 105 HeLa cells/well were plated on glass coverslips placed in 35-mm wells 24 h before experiments. Trypomastigotes were washed twice with PBS and resuspended in 2% FBS-DME or 2% FBS-DME Ca2+ free (Invitrogen) with 2 mM EGTA. Coverslips with attached HeLa cells were then incubated with 108 T. cruzi trypomastigotes per well (final concentration of 5 × 107/ml) for the indicated periods of time at 37°C and washed five times with PBS to remove extracellular parasites. Samples were fixed for 5 min at room temperature with Bouin solution (71.4% saturated picric acid, 23.8% formaldehyde, and 4.8% acetic acid), stained with Giemsa, and sequentially dehydrated in acetone, followed by a graded series of acetone/xylol (9:1, 7:3, and 3:7) and, finally, xylol. This technique allows microscopic distinction between intracellular parasites, which are seen surrounded by a halo, from attached parasites. The number of intracellular parasites was determined by counting at least 300 cells per coverslip in triplicate in a microscope (E200; Nikon) with a 100× 1.3 N.A. oil immersion objective. For immunofluorescence, coverslips were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) diluted in PBS for 15 min and processed as described in the next section.

Immunofluorescence.

PFA-fixed cells were washed with PBS, quenched with 15 mM NH4Cl for 15 min, and incubated with PBS containing 2% BSA for 1 h. When processed for an inside/outside immunofluorescence assay (Tardieux et al., 1992), samples were incubated with rabbit anti–T. cruzi polyclonal antibodies for 1 h, followed by 1 h of anti–rabbit IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 594 secondary antibodies, to stain extracellular parasites. Cells were then permeabilized with 0.1% saponin for 30 min and incubated with mouse monoclonal antibodies to EEA1 (BD) for 1 h, followed by anti–mouse Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibodies. For double labeling of EEA1 and Lamp1, coverslips permeabilized with 0.1% saponin were incubated with rabbit anti-EEA1 monoclonal antibodies and H4A3 anti–human Lamp1 mouse monoclonal antibodies (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank) for 1 h, followed by anti–rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor 488 and anti–mouse IgG Alexa Fluor 594. The number of internalized parasites (negative for anti–T. cruzi antibody staining) that were positive or negative for EEA1 staining was determined using an epifluorescence microscope (E200) with a 100× 1.3 N.A. oil immersion objective in at least 300 cells. Images in Fig. 6 are maximum projections of optical sections (0.13 µm Z step) acquired on a confocal system (SPX5; Leica) with a 63× 1.4 N.A. oil objective. Ceramide and Lamp1 double staining was performed by sequential incubation with antibodies after blocking with 2% BSA as described. Samples were then permeabilized with 0.1% saponin for 30 min and incubated with H4A3 anti–human Lamp1 monoclonal antibodies (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank) for 1 h followed by anti–mouse IgG Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibodies. Cells were then permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 5 min (a condition which extracts ceramide more efficiently from T. cruzi than from host cells; Fig. S5) and incubated with anti-ceramide IgM monoclonal antibodies (clone 15B4; Sigma-Aldrich) or IgM isotope control (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h, followed by anti–mouse IgM Alexa Fluor 594 secondary antibodies. After transferring images to Volocity suite (PerkinElmer), the total fluorescence intensity of the channel was divided by the number of cells present in the field to determine the mean fluorescence intensity per cell (Fig. S5). For the quantification of ceramide- and Lamp1-positive parasites (Figs. 8 and 9), Z stacks (0.13 µm Z step between optical sections) of 15 random fields (at least 200 cells) were imaged with a confocal system (SPX5) with a 63× 1.4 N.A. oil objective. Stacks of individual channels (2,048 × 2,048 pixels) were imported to Volocity Suite (PerkinElmer), and parasites were considered ceramide- or Lamp1-positive when staining outlining trypomastigotes could be visualized through several optical sections. To label ceramide present on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane (Fig. 5), nonpermeabilized fixed cells were incubated for 1 h with 15B4 anti-ceramide monoclonal antibodies, followed by Alexa Fluor 488–labeled secondary antibodies. Images were acquired using a microscope (E200) with a 40× 0.7 N.A. objective, equipped with a camera (DS-Fi1; Nikon) and Digital Sight. All samples were incubated with 10 µM DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich) for nuclei staining. Secondary antibodies were purchased from Invitrogen. For Lamp1 and GPI double labeling (Fig. 7), subconfluent cells were transduced using adenovirus encoding Lamp1-RFP and GPI-YFP, as described previously (Flannery et al., 2010), and imaged using a confocal system (SPX5) with a 63× 1.4 N.A. oil objective.

Drug, enzyme, and toxin treatments.

Cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of BEL (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min or Desipramine (Sigma-Aldrich) for 60 min before invasion experiments. Histidine-tagged SLO (carrying a cysteine deletion which eliminates the need for thiol activation) was provided by R. Tweeten (University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK) and purified as described previously (Idone et al., 2008). SLO was added to the media at indicated concentrations either before or during invasion assays. Bacillus cereus sphingomyelinase (Sigma-Aldrich) was incubated with HeLa cells at the indicated concentrations for the indicated time periods either before or during incubation with trypomastigotes (described in figure legends).

ASM transcriptional silencing and Western blots.

1.4 × 105 HeLa cells plated in 35-mm wells were transfected with Lipofectamine and 160 pmol of control (medium GC content, 12935300) or SMPD1 (HSS143988–(RNA)–GCCCUGCCGUCUGGCUACUCUUUGU) stealth siRNA duplexes according to the manufacturer’s instruction (Invitrogen). Cells were used for invasion assays 72 h after transfection. Western blot for ASM was performed on cell lysates separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and incubated with affinity-purified anti-ASM rabbit antibodies (provided by Y. Hannun [Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC] and prepared as previously described [Zeidan and Hannun, 2007]).

Live cell imaging.

For live time-lapse fluorescence imaging, subconfluent cells were plated on 35-mm glass-bottom dishes (Mattek) and transduced using adenovirus encoding Lamp1-RFP as described previously (Flannery et al., 2010). 20 min after addition of trypomastigotes, dishes were transferred to an environmental chamber (Pathology Devices) at 37°C with 5% CO2 and humidity control. Spinning disk confocal images were acquired for 13 h at 1 frame/100 s for the initial 96 min and 1 frame every 10 min for the remaining period using the UltraVIEW VoX system (PerkinElmer) attached to an inverted microscope (Eclipse Ti; Nikon) with a 60× 1.4 N.A. objective and equipped with a camera (C9100-50; Hamamatsu). Acquisition and image processing was performed using Volocity Suite (PerkinElmer).

For live time-lapse phase-contrast imaging, subconfluent cells were plated on glass-bottom dishes (Mattek) and incubated with 5 × 107/ml trypomastigotes for 10 min. Cells were then washed three times with PBS before addition of fresh DME containing 20 mM Hepes at pH 7.2. Dishes were placed on a heated stage (37°C) and imaged in a 200 microscope (Axiovert; Carl Zeiss) with a 63× 1.3 N.A. objective, equipped with a Cool Snap HQ camera and MetaMorph software. Image processing was performed using Volocity Suite (PerkinElmer).

Scanning electron microscopy.

Samples attached to glass coverslips were fixed at the indicated time periods in 2% glutaraldehyde, 2% paraformaldehyde, and 0.1 M Hepes, pH 7.0, for 1 h at room temperature. Samples were postfixed in 1% OsO4 in 0.1 M Hepes, pH 7.4, for 1 h and then exposed to 1% tannic acid for another hour before dehydration in an ethanol series, critical point dried from CO2, and gold sputtered (Goldberg and Allen, 1992). Images were acquired on a field emission scanning electron microscope (S-4800; Hitachi) operated at 5 kV. All reagents were obtained from Electron Microscopy Sciences.

Flow cytometry and PI staining.

To determine plasma membrane integrity during trypomastigote entry and SLO incubation, assays were performed as described in the previous sections in the presence or absence of Ca2+, in DME containing 25 µg/ml PI (Sigma-Aldrich), and followed by microscopic quantification and epifluorescence imaging using a microscope (E200) with a 63× 1.3 N.A. objective, equipped with a camera (DS-Fi1) and Digital Sight. When specified in legends, cells were fixed with PFA and stained with 10 µM DAPI prior imaging. For flow cytometry, HeLa cells in 35-mm wells exposed to T. cruzi trypomastigotes or epimastigotes were trypsinized, fixed with PFA, and at least 10,000 cells were analyzed in a FACSCanto (BD). The data were processed using FlowJo software (version 6.3; Tree Star).

Online supplemental material.

Fig. S1 shows that infective T. cruzi trypomastigotes wound host cells. Fig. S2 shows that SLO permeabilizes the plasma membrane of mammalian cells but not T. cruzi trypomastigotes. Fig. S3 shows that inhibition of lysosomal exocytosis blocks trypomastigote entry. Fig. S4 shows control assays for ceramide immunolabeling. Fig. S5 shows that ceramide is extracted more efficiently from trypomastigotes than host cells after Triton X-100 permeabilization. Video 1 shows exocytosis of host cell lysosomes during interaction with T. cruzi trypomastigotes. Video 2 shows that extracellular trypomastigotes cause mechanical deformations in the host cell membrane before invasion. Video 3 shows invasion and intracellular motility of T. cruzi. Video 4 shows protrusion of motile intracellular trypomastigotes from the surface of host cells. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20102518/DC1.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Leonardo de Andrade Rodrigues and Dr. Bechara Kachar (both from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, National Institutes of Health [NIH]) for generously providing technical help and access to the field emission–scanning electron microscope, and Amy Beaven and the Department of Cell Biology and Molecular Genetics Imaging Core for assistance with confocal microscopy.

This work was supported by the NIH grant R37 AI34867 to N.W. Andrews.

The authors do not have any competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used:

- ASM

- acid sphingomyelinase

- BEL

- bromoenol lactone

- EEA1

- early endosome antigen 1

- GPI

- glycosyl phosphatidylinositol

- Lamp1

- lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1

- PI

- propidium iodide

- SLO

- Streptolysin O

References

- Andrade L.O., Andrews N.W. 2004. Lysosomal fusion is essential for the retention of Trypanosoma cruzi inside host cells. J. Exp. Med. 200:1135–1143 10.1084/jem.20041408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews N.W., Whitlow M.B. 1989. Secretion by Trypanosoma cruzi of a hemolysin active at low pH. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 33:249–256 10.1016/0166-6851(89)90086-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews N.W., Hong K.S., Robbins E.S., Nussenzweig V. 1987. Stage-specific surface antigens expressed during the morphogenesis of vertebrate forms of Trypanosoma cruzi. Exp. Parasitol. 64:474–484 10.1016/0014-4894(87)90062-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews N.W., Abrams C.K., Slatin S.L., Griffiths G. 1990. A T. cruzi-secreted protein immunologically related to the complement component C9: evidence for membrane pore-forming activity at low pH. Cell. 61:1277–1287 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90692-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertello L.E., Andrews N.W., de Lederkremer R.M. 1996. Developmentally regulated expression of ceramide in Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 79:143–151 10.1016/0166-6851(96)02645-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi G.Q., Alderton J.M., Steinhardt R.A. 1995. Calcium-regulated exocytosis is required for cell membrane resealing. J. Cell Biol. 131:1747–1758 10.1083/jcb.131.6.1747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burleigh B.A., Andrews N.W. 1995. A 120-kDa alkaline peptidase from Trypanosoma cruzi is involved in the generation of a novel Ca(2+)-signaling factor for mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 270:5172–5180 10.1074/jbc.270.10.5172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burleigh B.A., Andrews N.W. 1998. Signaling and host cell invasion by Trypanosoma cruzi. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 1:461–465 10.1016/S1369-5274(98)80066-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burleigh B.A., Woolsey A.M. 2002. Cell signalling and Trypanosoma cruzi invasion. Cell. Microbiol. 4:701–711 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2002.00226.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burleigh B.A., Caler E.V., Webster P., Andrews N.W. 1997. A cytosolic serine endopeptidase from Trypanosoma cruzi is required for the generation of Ca2+ signaling in mammalian cells. J. Cell Biol. 136:609–620 10.1083/jcb.136.3.609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers R., Chambers E.L. 1961. Explorations into the nature of the living cell. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA: 352 pp [Google Scholar]

- Falkow S., Isberg R.R., Portnoy D.A. 1992. The interaction of bacteria with mammalian cells. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 8:333–363 10.1146/annurev.cb.08.110192.002001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fensome-Green A., Stannard N., Li M., Bolsover S., Cockcroft S. 2007. Bromoenol lactone, an inhibitor of Group V1A calcium-independent phospholipase A2 inhibits antigen-stimulated mast cell exocytosis without blocking Ca2+ influx. Cell Calcium. 41:145–153 10.1016/j.ceca.2006.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes M.C., Cortez M., Geraldo Yoneyama K.A., Straus A.H., Yoshida N., Mortara R.A. 2007. Novel strategy in Trypanosoma cruzi cell invasion: implication of cholesterol and host cell microdomains. Int. J. Parasitol. 37:1431–1441 10.1016/j.ijpara.2007.04.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flannery A.R., Czibener C., Andrews N.W. 2010. Palmitoylation-dependent association with CD63 targets the Ca2+ sensor synaptotagmin VII to lysosomes. J. Cell Biol. 191:599–613 10.1083/jcb.201003021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg M.W., Allen T.D. 1992. High resolution scanning electron microscopy of the nuclear envelope: demonstration of a new, regular, fibrous lattice attached to the baskets of the nucleoplasmic face of the nuclear pores. J. Cell Biol. 119:1429–1440 10.1083/jcb.119.6.1429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassmé H., Riethmüller J., Gulbins E. 2007. Biological aspects of ceramide-enriched membrane domains. Prog. Lipid Res. 46:161–170 10.1016/j.plipres.2007.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulbins E., Kolesnick R. 2003. Raft ceramide in molecular medicine. Oncogene. 22:7070–7077 10.1038/sj.onc.1207146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilbrunn L. 1956. The dynamics of living protoplasm. Academic Press, New York: 327 pp [Google Scholar]

- Hill K.L. 2003. Biology and mechanism of trypanosome cell motility. Eukaryot. Cell. 2:200–208 10.1128/EC.2.2.200-208.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holopainen J.M., Angelova M.I., Kinnunen P.K. 2000. Vectorial budding of vesicles by asymmetrical enzymatic formation of ceramide in giant liposomes. Biophys. J. 78:830–838 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76640-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurwitz R., Ferlinz K., Sandhoff K. 1994. The tricyclic antidepressant desipramine causes proteolytic degradation of lysosomal sphingomyelinase in human fibroblasts. Biol. Chem. Hoppe Seyler. 375:447–450 10.1515/bchm3.1994.375.7.447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde T.P., Dvorak J.A. 1973. Trypanosoma cruzi: interaction with vertebrate cells in vitro. 2. Quantitative analysis of the penetration phase. Exp. Parasitol. 34:284–294 10.1016/0014-4894(73)90088-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idone V., Tam C., Goss J.W., Toomre D., Pypaert M., Andrews N.W. 2008. Repair of injured plasma membrane by rapid Ca2+-dependent endocytosis. J. Cell Biol. 180:905–914 10.1083/jcb.200708010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal J.K., Andrews N.W., Simon S.M. 2002. Membrane proximal lysosomes are the major vesicles responsible for calcium-dependent exocytosis in nonsecretory cells. J. Cell Biol. 159:625–635 10.1083/jcb.200208154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kölzer M., Ferlinz K., Bartelsen O., Hoops S.L., Lang F., Sandhoff K. 2004. Functional characterization of the postulated intramolecular sphingolipid activator protein domain of human acid sphingomyelinase. Biol. Chem. 385:1193–1195 10.1515/BC.2004.154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koval M., Pagano R.E. 1991. Intracellular transport and metabolism of sphingomyelin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1082:113–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley V., Robbins E.S., Nussenzweig V., Andrews N.W. 1990. The exit of Trypanosoma cruzi from the phagosome is inhibited by raising the pH of acidic compartments. J. Exp. Med. 171:401–413 10.1084/jem.171.2.401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil P.L., Steinhardt R.A. 2003. Plasma membrane disruption: repair, prevention, adaptation. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 19:697–731 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.111301.140101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil P.L., Vogel S.S., Miyake K., Terasaki M. 2000. Patching plasma membrane disruptions with cytoplasmic membrane. J. Cell Sci. 113:1891–1902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake K., McNeil P.L. 1995. Vesicle accumulation and exocytosis at sites of plasma membrane disruption. J. Cell Biol. 131:1737–1745 10.1083/jcb.131.6.1737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno S.N., Silva J., Vercesi A.E., Docampo R. 1994. Cytosolic-free calcium elevation in Trypanosoma cruzi is required for cell invasion. J. Exp. Med. 180:1535–1540 10.1084/jem.180.4.1535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulder J.W. 1985. Comparative biology of intracellular parasitism. Microbiol. Rev. 49:298–337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogueira N., Cohn Z. 1976. Trypanosoma cruzi: mechanism of entry and intracellular fate in mammalian cells. J. Exp. Med. 143:1402–1420 10.1084/jem.143.6.1402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy A., Caler E.V., Andrews N.W. 2001. Plasma membrane repair is mediated by Ca(2+)-regulated exocytosis of lysosomes. Cell. 106:157–169 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00421-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez A., Rioult M.G., Ora A., Andrews N.W. 1995. A trypanosome-soluble factor induces IP3 formation, intracellular Ca2+ mobilization and microfilament rearrangement in host cells. J. Cell Biol. 129:1263–1273 10.1083/jcb.129.5.1263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez A., Webster P., Ortego J., Andrews N.W. 1997. Lysosomes behave as Ca2+-regulated exocytic vesicles in fibroblasts and epithelial cells. J. Cell Biol. 137:93–104 10.1083/jcb.137.1.93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenkman S., Mortara R.A. 1992. HeLa cells extend and internalize pseudopodia during active invasion by Trypanosoma cruzi trypomastigotes. J. Cell Sci. 101:895–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenkman S., Robbins E.S., Nussenzweig V. 1991. Attachment of Trypanosoma cruzi to mammalian cells requires parasite energy, and invasion can be independent of the target cell cytoskeleton. Infect. Immun. 59:645–654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schissel S.L., Jiang X., Tweedie-Hardman J., Jeong T., Camejo E.H., Najib J., Rapp J.H., Williams K.J., Tabas I. 1998. Secretory sphingomyelinase, a product of the acid sphingomyelinase gene, can hydrolyze atherogenic lipoproteins at neutral pH. Implications for atherosclerotic lesion development. J. Biol. Chem. 273:2738–2746 10.1074/jbc.273.5.2738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhardt R.A., Bi G., Alderton J.M. 1994. Cell membrane resealing by a vesicular mechanism similar to neurotransmitter release. Science. 263:390–393 10.1126/science.7904084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam C., Idone V., Devlin C., Fernandes M.C., Flannery A., He X., Schuchman E., Tabas I., Andrews N.W. 2010. Exocytosis of acid sphingomyelinase by wounded cells promotes endocytosis and plasma membrane repair. J. Cell Biol. 189:1027–1038 10.1083/jcb.201003053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tardieux I., Webster P., Ravesloot J., Boron W., Lunn J.A., Heuser J.E., Andrews N.W. 1992. Lysosome recruitment and fusion are early events required for trypanosome invasion of mammalian cells. Cell. 71:1117–1130 10.1016/S0092-8674(05)80061-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tardieux I., Nathanson M.H., Andrews N.W. 1994. Role in host cell invasion of Trypanosoma cruzi-induced cytosolic-free Ca2+ transients. J. Exp. Med. 179:1017–1022 10.1084/jem.179.3.1017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Togo T., Alderton J.M., Bi G.Q., Steinhardt R.A. 1999. The mechanism of facilitated cell membrane resealing. J. Cell Sci. 112:719–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trajkovic K., Hsu C., Chiantia S., Rajendran L., Wenzel D., Wieland F., Schwille P., Brügger B., Simons M. 2008. Ceramide triggers budding of exosome vesicles into multivesicular endosomes. Science. 319:1244–1247 10.1126/science.1153124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tweten R.K. 2005. Cholesterol-dependent cytolysins, a family of versatile pore-forming toxins. Infect. Immun. 73:6199–6209 10.1128/IAI.73.10.6199-6209.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Blitterswijk W.J., van der Luit A.H., Veldman R.J., Verheij M., Borst J. 2003. Ceramide: second messenger or modulator of membrane structure and dynamics? Biochem. J. 369:199–211 10.1042/BJ20021528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walev I., Bhakdi S.C., Hofmann F., Djonder N., Valeva A., Aktories K., Bhakdi S. 2001. Delivery of proteins into living cells by reversible membrane permeabilization with streptolysin-O. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:3185–3190 10.1073/pnas.051429498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolsey A.M., Sunwoo L., Petersen C.A., Brachmann S.M., Cantley L.C., Burleigh B.A. 2003. Novel PI 3-kinase-dependent mechanisms of trypanosome invasion and vacuole maturation. J. Cell Sci. 116:3611–3622 10.1242/jcs.00666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida N., Cortez M. 2008. Trypanosoma cruzi: parasite and host cell signaling during the invasion process. Subcell. Biochem. 47:82–91 10.1007/978-0-387-78267-6_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeidan Y.H., Hannun Y.A. 2007. Activation of acid sphingomyelinase by protein kinase Cdelta-mediated phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 282:11549–11561 10.1074/jbc.M609424200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zha X., Pierini L.M., Leopold P.L., Skiba P.J., Tabas I., Maxfield F.R. 1998. Sphingomyelinase treatment induces ATP-independent endocytosis. J. Cell Biol. 140:39–47 10.1083/jcb.140.1.39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]