Abstract

Although the CNS melanocortin system is an important regulator of energy balance, the role of proopiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons in mediating the chronic effects of leptin on appetite, blood pressure, and glucose regulation is unknown. Using Cre/loxP technology we tested whether leptin receptor deletion in POMC neurons (LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice) attenuates the chronic effects of leptin to increase mean arterial pressure (MAP), enhance glucose utilization and oxygen consumption (VO2), and reduce appetite. LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre, wild-type (WT), LepRflox/flox and POMC-Cre mice were instrumented for MAP and heart rate (HR) measurement by telemetry, and venous catheters for infusions. LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice were heavier, hyperglycemic, hyperinsulinemic, and hyperleptinemic compared to WT, LepRflox/flox and POMC-Cre mice. Despite exhibiting features of metabolic syndrome, LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice had normal MAP and HR compared to LepRflox/flox but lower MAP and HR compared to WT mice. After a 5-day control period, leptin was infused (2 μg/kg/min, i.v.) for 7 days. In control mice, leptin increased MAP by ~5 mmHg despite decreasing food intake by ~35%. In contrast, leptin infusion in LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice reduced MAP by ~3 mmHg and food intake by ~28%. Leptin significantly decreased insulin and glucose levels in control mice but not in LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice. Leptin increased VO2 in LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre and WT mice. Activation of POMC neurons is necessary for the chronic effects of leptin to raise MAP and reduce insulin and glucose levels, whereas leptin receptors in other areas of the brain besides POMC neurons appear to play a key role in mediating leptin’s chronic effects on appetite and VO2.

Keywords: Food intake, blood pressure, heart rate, acute stress, baroreceptor sensitivity

INTRODUCTION

Leptin, a 16 kD protein secreted by adipocytes in proportion to body fat mass, acts on the central nervous system (CNS) to regulate body weight by controlling appetite and energy expenditure1–4. Leptin deficiency or lack of functional leptin receptors is associated with pronounced hyperphagia and reduced energy expenditure5–9, whereas chronic increases in leptin, by overexpression of the leptin gene using viral vectors or leptin infusions, reduce food intake and increase energy expenditure10–12. The latter is mainly a consequence of increased sympathetic nerve activity (SNA) to thermogenic tissues such as brown adipose tissue13.

Leptin also plays an important role in glucose homeostasis. For instance, patients with lipodystrophy who have low circulating leptin levels are severely insulin resistant and leptin replacement therapy markedly improves their insulin sensitivity and restores glycemic control14. An important part of leptin’s effects on glucose homeostasis is mediated by direct actions on the CNS15,16. However, the specific neuronal populations that mediate the chronic CNS effects of leptin on glucose homeostasis are still unclear.

Leptin may also be an important link between obesity, SNA and hypertension17. We and others have shown that leptin administration increases SNA and blood pressure, and that leptin-mediated increases in blood pressure can be completely prevented by adrenergic blockade18. Moreover, mice that are leptin-deficient have normal or reduced blood pressure despite severe obesity suggesting that a functional leptin system may be necessary for obesity to increase SNA and blood pressure.

Although the precise CNS mechanisms by which leptin chronically regulates energy balance, glucose homeostasis and blood pressure are not fully understood, previous studies suggest that the CNS melanocortin system may play an important role. Five melanocortin receptors have been described (MC1R to MC5R), although the most prevalent melanocortin receptors in CNS are the MC3R and MC4R19. Acute studies indicate that activation of CNS MC3/4R using pharmacological agonists reduces food intake, increases thermogenesis, enhances peripheral glucose utilization, and raises blood pressure20–22. Chronic blockade of these receptors causes marked hyperphagia, obesity, hyperinsulinemia and hyperglycemia, and reduced blood pressure21,23. Blockade of MC3/4R also markedly attenuated the chronic effects of leptin to suppress appetite, reduce plasma glucose, and raise blood pressure24. Also, MC4R deficient mice, despite being severely obese and exhibiting many features of the metabolic syndrome, are not hypertensive12,25 and do not have a hypertensive response to chronic hyperleptinemia12.

The classic view of interactions between leptin and the melanocortin system is that activation of leptin receptors in POMC neurons, especially those located in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus (ARC), leads to depolarization of these neurons and release of α-melanocyte stimulated hormone (α-MSH) which is the endogenous agonist of the MC4R26. Recent studies, however, have shown that deletion of leptin receptors in POMC neurons does not recapitulate the severe obesity and hyperphagia observed in leptin deficient models or MC4R deficient mice20. These observations indicate that interactions of the leptin-POMC/MC4R axis are more complex that originally thought.

In the present study we used a genetic approach to investigate the role of leptin receptors on POMC neurons in regulating blood pressure, baroreflex sensitivity and cardiovascular responses to acute stress, appetite, VO2, and control of plasma glucose. Our studies indicate that activation of leptin receptors in POMC neurons is necessary for leptin to raise blood pressure and to reduce plasma insulin and glucose, but is not required for leptin to reduce appetite or to increase VO2.

METHODS

The experimental procedures and protocols for these studies followed the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Mississippi Medical Center.

Animals

Male 22-week-old C57BL/6J wild type (WT, n=23), LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre (n=26), LepRflox/flox (n=4) and POMC-Cre (n=3) mice were used in these studies. LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice were generated by crossing POMC-Cre mice that express Cre-recombinase specifically in POMC neurons on a Friend Virus B (FVB) background (generously provided by Dr. Joel Elmquist, Southwestern Texas University, Dallas, TX) with LepRflox/flox (129-C57Bl/6J x FVB N2) mice (generously provided by Dr. Jeffrey Friedman, The Rockefeller University, New York, NY). Homozygous mice for the LepRflox/flox gene that also expressed Cre-recombinase were used as LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice (please see http://hyper.ahajournals.org, Figure S1). Littermate homozygous LepRflox/flox and POMC-Cre mice from our colony as well as WT mice, purchased from the Jackson Laboratories, were used as controls for the chronic experiments. Because we observed no significant differences in the responses to chronic leptin infusion between WT, POMC-Cre and LepRflox/flox mice and since our previous studies examining the actions of leptin were conducted in WT mice we opted to use WT mice as controls in the acute experiments.

Specificity of Cre expression in POMC neurons and selective deletion of LepR in POMC neurons have been reported previously20. To further validate the deletion of leptin receptors in POMC neurons in the present study, we used PCR analyses to genotype the mice and immunohistochemistry to verify reduced leptin-mediated signaling as assessed by decreased LepR immunoreactivity on POMC neurons in LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice compared to control mice, as well as decreased p-STAT3 immunoreactivity after intraperitoneal leptin injection.

Telemetry probe and venous catheter implantation

Under isoflurane anesthesia, male LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre (n=7), WT (n=6), LepRflox/flox (n=4) and POMC-Cre (n=3) mice were implanted with telemetric pressure transmitter probes in the left carotid artery for determination of mean arterial pressure (MAP) and heart rate (HR) 24-hours per day using computerized methods for data collection as previously described12,25. Daily MAP and HR were obtained from the average of 24 hours of recording using a sampling rate of 500 Hz with duration of 10 seconds for every 10–minute period. A venous catheter was also implanted in the jugular vein for infusions of saline vehicle or leptin. The venous catheter was tunneled subcutaneously, exteriorized between the scapulae, and passed through a spring connected to a mouse swivel (Instech) mounted on the top of the plastic metabolic cage. The venous catheter was connected through a sterile filter to a syringe pump for continuous saline and leptin infusions. Food and water were offered ad libitum throughout the experiment and room temperature was maintained at 23 to 24°C. A normal sodium intake of ~460 μmol/day was maintained via the constant saline infusion combined with sodium-deficient rodent chow as previously described12. The mice were allowed to recover for 8 to 10 days after the surgery before baseline measurements were taken.

Experimental design

Acute leptin injection

To determine the role of leptin receptor activation in POMC neurons in mediating the acute effects of leptin on appetite, food intake was measured 2, 4, 15 and 24 hours after intraperitoneal leptin (10 mg/kg) or saline vehicle injection (0.3 ml) between 5 and 6 pm in a separate group of non-instrumented and non-fasted WT (n=5) and LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice (n=5) at 22 weeks of age.

Chronic leptin infusion

After an 8–10 day post-surgery recovery period and 5-days of stable baseline control measurements, leptin was added to the saline vehicle infusion at the rate of 2 μg/kg/min in additional groups of WT (n=6), LepRflox/flox (n=4), POMC-Cre (n=3) and LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice (n=7) for 7 days followed by a 5-day post-treatment period during which only saline vehicle was infused intravenously. MAP, HR, urine volume, and food and water intake were recorded daily. Blood samples (100 μL) were collected via a tail snip after 6–hours of fasting (8:00 am to 2:00 pm) during the control period (day 5), on the last day of leptin infusion (day7) and at the end of the post-treatment period for measurements of plasma glucose, leptin and insulin concentrations.

Acute air-jet stress test

To determine the whether leptin receptor deletion in POMC neurons alters the MAP and HR responses to an acute pressor stress, LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre (n=6) and WT (n=5) mice were placed in a special cage used for air-jet stress testing. Briefly, after a 2-hour period for acclimatization to the cage, MAP and HR were continuously measured, using telemetry, for 30 minutes before the air-jet stress test was applied. The air-jet stress test consisted of 2-second pulses of air jet delivery every 5 seconds during 5 consecutive minutes aimed at the forehead of the mice at an approximately distance of 5 cm using a 14 gauge needle opening at the front of the tube connected to compressed air. After the 5-minute air-jet stress, MAP and HR were measured for an additional 30-minute recovery period. BP and HR responses during the air-jet stress and recovery period following the air-jet stress were calculated as the changes compared to baseline period (average of the last 10 minutes of baseline measurements before air-jet stress was initiated). We also calculated the areas under the MAP and HR curve (AUC) during the air-jet stress and recovery periods using the following parameters: average change in MAP for each minute during the 5-minute air-jet stress test and for each 5 minutes during the 30-minute recovery period.

Spontaneous baroreflex sensitivity (BRS) and power spectral analyses of systolic arterial pressure (SAP) and RR interval (RRI) oscillations

To assess the impact of leptin receptor deletion in POMC neurons on reflex control of cardiovascular function, we measured spontaneous baroreflex sensitivity (BRS) by the sequence method as previously described27. We also computed power spectral densities of systolic arterial pressure (SAP) and RR interval (RRI) oscillations by 512-point fast Fourier transform integrated over the specific frequency range (low frequency: LF, 0.25–0.75 Hz; high frequency: HF, 0.75–5.0 Hz) using Nevrokard SA-BRS software (Medistar, Ljubjana, Slovenia) (please see http://hyper.ahajournals.org).

Oxygen consumption and motor activity

In separate experiments, WT (n=5) and LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice (n=6) at 22 weeks of age were placed individually in metabolic cages (AccuScan Instruments Inc, Columbus, OH) equipped with oxygen sensors to measure oxygen consumption (VO2) and infrared beams to determine motor activity. VO2 was measured for 2-min at 10-minute intervals continuously 24-hours a day using a Zirconia oxygen sensor. Motor activity was determined using infrared light beams mounted in the cages in X, Y and Z axes. After the mice were acclimatized to the new environment for approximately 4–6 days, VO2 and animal activity were recorded for 3 consecutive days. Then the mice were lightly anesthetized with isoflurane and an osmotic minipump (model 1007D, Durect Corp.) was placed subcutaneously in the scapular region and connected to a catheter inserted in the left jugular vein and routed subcutaneously to the scapular region to deliver leptin (2 μg/kg/min) for 7 days. At the end of the leptin infusion period, the catheter connecting the minipump to the jugular vein was severed and sealed, and the mice were followed for an additional 5-day post-treatment period.

Analytical methods

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Genotyping was performed as previously described20 (please see http://hyper.ahajournals.org).

Immunohistochemistry

To confirm deletion of LepR on POMC neurons we used immunohistochemistry to double label LepR and POMC neurons in sections of the arcuate nucleus (see supplementary online material). Also, we double labeled sections of the hypothalamus for POMC and p-STAT3, a primary signaling pathway for LepR activation. LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre and LepRflox/flox mice (n=3 per group) were injected intraperitoneally with recombinant mouse leptin (R&D Systems, MN; 5 mg/kg). After 45 minutes, animals were perfused, via a cannula inserted into the left ventricle, with phosphate-buffered saline containing phosphatase inhibitor (Roche Inc., USA); tissues were collected and kept overnight in formalin, after which the solution was switched to 20% sucrose and tissues were kept overnight at 4°C. Frozen brain coronal sections, 40 μm thick were cut and processed for immunofluorescence to verify the presence of LepR and p-STAT3 immunoreactivity in POMC neurons in the ARC (please see http://hyper.ahajournals.org).

Plasma hormones and glucose measurements

Plasma leptin and insulin concentrations were measured with an ELISA kit (R&D Systems and Crystal Chem Inc., respectively), and plasma glucose concentrations were determined using the glucose oxidation method (Beckman glucose analyzer 2).

Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as means ± SEM. Data were analyzed by paired t test or 1-way ANOVA with repeated measures followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test for comparisons between control and experimental values within each group when appropriate. Comparisons between different groups were made by unpaired t test or 1-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test when appropriate. Statistical significance was accepted at a level of P<0.05.

RESULTS

Double-labeling immunofluorescence of POMC neurons with leptin receptor or p-STAT3 in the hypothalamus of LepRflox/flox and LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice after acute leptin injection

As expected, we found abundant positive staining in POMC neurons for leptin receptors and p-STAT3, a major signaling pathway for leptin, in the arcuate nucleus of LepRflox/flox control mice after acute ip leptin injection. However, staining for leptin receptors and p-STAT3 in POMC neurons was markedly reduced in LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice brains (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Top, POMC positive neurons (arrows in panels A and D) and LepR positive cells (arrows in panels B and E) were detected in the arcuate nucleus (ARC) of LepRflox/flox and LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice. The merged images show markedly reduced co-localization of POMC (arrow heads) and LepR in LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice (panel F) compared to LepRflox/flox mice (panel C). Bottom, POMC positive neurons (arrows in panels G and J) and p-STAT3 positive cells (arrows in panels H and K) were detected in the ARC of LepRflox/flox and LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice. The merged image shows markedly reduced co-localization of POMC (arrow heads) and p-STAT3 in LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice (panel L) compared to LepRflox/flox mice (panel I). Scale bar represents 50 μm.

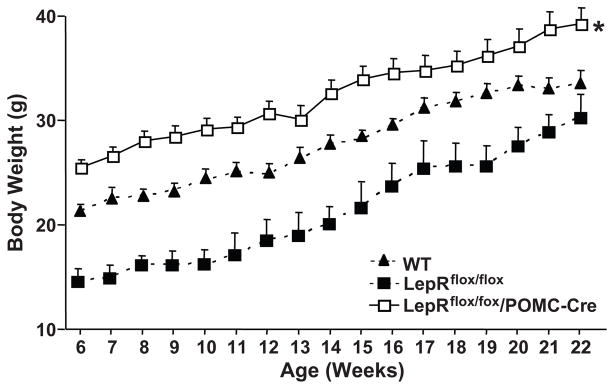

Effect of LepR deletion in POMC neurons on body length and weight, and visceral fat

No significant differences in body length (nasal to anal distance) were observed among the groups (Table 1). Mice with leptin receptor deletion in POMC neurons were significantly heavier (~24%) than WT and LepRflox/flox mice as early as 6 weeks of age, and this difference persisted until 22 weeks of age when experiments were initiated (Figure 2 and Table 1). The increased body weight in LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice was associated with almost a doubling of epididymal fat mass (Table 1). At least part of the increased body weight and visceral fat content in LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice may be due to hyperphagia since at baseline these mice consumed on average 25% more food than WT and LepRflox/flox mice (Figure 2B). Body weight of LepRflox/flox mice was slightly lower at around 6 weeks of age compared to WT and LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice but when the acute and chronic protocols were started (22 weeks of age) no significant differences in body weight were observed in WT and LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Effects of chronic leptin infusion (2 μg/kg/min, i.v.) on body weight (BW), body length (BL), epididymal (Ep) fat weight, water intake, and urine volume (UV).

| Groups | BW (g) | BL (cm) | Ep. Fat (g) | Water Intake (ml/day) | UV (ml/day) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT (n=5) | |||||

| Control | 31±1 | 2.2±0.1 | 3.8±0.1 | ||

| Leptin | 28±1 † | 3.1±0.4 | 3.6±0.2 | ||

| Recovery | 31±1 | 10.0±0.1 | 0.72±0.12 | 3.5±0.2 | 4.4±0.1 |

| POMC-Cre (n=3) | |||||

| Control | 36±1 | 2.3±0.3 | 3.4±0.3 | ||

| Leptin | 33±2 | 2.7±0.3 | 3.7±0.1 | ||

| Recovery | 35±2 | 10.5±0.1 | 0.62±0.2 | 2.7±0.2 | 4.0±0.1 |

| LepRflox/flox (n=4) | |||||

| Control | 29±1 | 2.8±0.4 | 3.3±0.2 | ||

| Leptin | 27±1 | 3.9±0.1 | 3.6±0.3 | ||

| Recovery | 30±1 | 10.0±0.3 | 0.65±0.10 | 3.6±0.2 | 3.2±0.2 |

| LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre (n=7) | |||||

| Control | 38±1 | 3.1±0.2 | 2.5±0.1 | ||

| Leptin | 35±1 *,† | 3.3±0.2 | 2.7±0.1 | ||

| Recovery | 39±2 | 10.3±0.1 | 1.35±0.26* | 3.1±0.7 | 3.0±0.1 |

Values are mean±SEM.

P<0.05, compared to WT mice;

p<0.05 compared to control period.

Figure 2.

Body weight curve of male WT (n=5), LepRflox/flox (n=5), and LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre (n=5) mice. *p<0.05 compared to WT and LepRflox/flox mice.

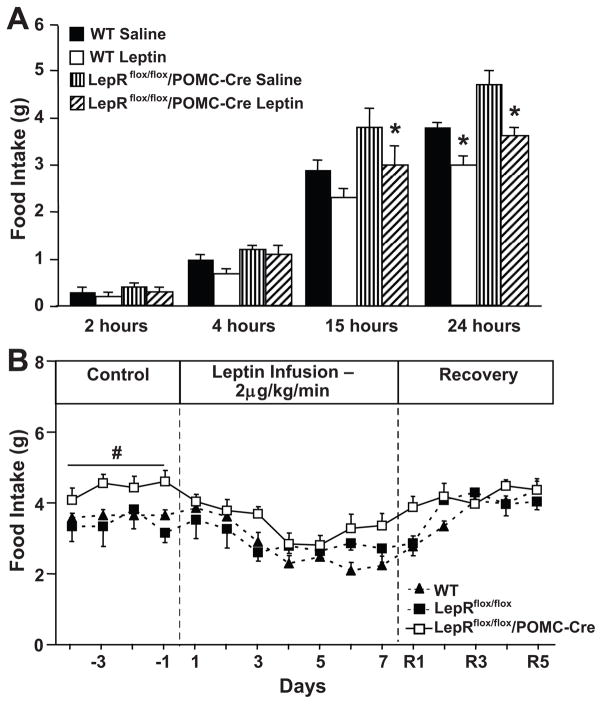

Acute and chronic effects of leptin on food intake, body weight and urine volume

Acute intraperitoneal leptin injection reduced 24-hour food intake in WT and LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice by ~20% when compared to saline vehicle injection (Figure 3A). The acute anorexic effect of leptin was observed as early as 15 hours post-injection in both groups. These results indicate that activation of leptin receptors in POMC neurons is not critical for the acute effects of leptin to reduce appetite. No changes in body weight were observed after acute leptin or saline injections (data not shown).

Figure 3.

(A) Response to acute leptin injection (10 mg/kg, i.p) on food intake. * p<0.05 compared to LepRflox/flox/POMC-cre (n=6) and WT (n=5) mice. (B) Response to chronic leptin infusion (2 μg/kg/min) for 7 days on 24-hour average food intake in WT (n=6), LepRflox/flox (n=4) and LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre (n=7) mice. # p<0.05 compared to saline-treated group.

Chronic i.v. infusion of leptin for 7 consecutive days markedly reduced food intake in WT, LepRflox/flox and LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice (Figure 3B). This reduction in food intake was associated with weight loss of approximately 10% in all three groups (Table 1). After stopping leptin infusion, food intake and body weight returned to baseline values in all groups (Figure 3B and Table 1). These results indicate that activation of leptin receptors in POMC neurons may not be critical in mediating the chronic anorexigenic actions of leptin and suggest an important role for other groups of neurons.

In order to determine whether the presence of Cre-recombinase may induce a phenotypic response to chronic leptin infusion we also investigated the anorexigenic effect of leptin in POMC-Cre mice. Chronic leptin infusion in these mice reduced food intake and body weight to the same extent as observed in WT and LepRflox/flox (please see http://hyper.ahajournals.org, Figure S2A and Table 1), thus indicating that the presence of Cre-recombinase, by itself, did not alter leptin’s ability to suppress appetite and to promote weight loss.

Water intake and urine volume were not significantly different among the groups at baseline and were not significantly altered by chronic leptin infusion (Table 1).

MAP and HR responses to acute air-jet stress and to chronic leptin infusion

Baseline MAP and HR were significantly lower in LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre and Leprflox/flox mice when compared to age-matched WT control (Figures 4A and 4B). In WT, LepRflox/flox and POMC-Cre control mice chronic leptin infusion caused a gradual and progressive elevation in MAP and HR, despite decreased food intake and weight loss, whereas in LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice leptin failed to increase MAP and HR (Figures 4A, 4B and S2). In fact, leptin caused a small (~3 mmHg), although not statistically significant, reduction in MAP and HR in LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice. These data indicate that leptin receptors in POMC neurons are required for the chronic effects of leptin to increase arterial pressure. These data also show that Cre-recombinase, by itself, did not contribute to the differential pressor response to leptin in LepRflox/flox-POMC-Cre mice.

Figure 4.

Response to chronic leptin infusion (2 μg/kg/min) for 7 days on (A) 24-hour average mean arterial pressure (MAP) and (B) heart rate (HR) in WT (n=6) LepRflox/flox (n=4) and LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre (n=7) mice. # p<0.05 compared to WT and LepRflox/flox mice; * p<0.05 compared to baseline values.

LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice also exhibited impaired MAP and HR responses to acute stress (Figures 5A, 5B and 5C), suggesting that these animals not only have lower baseline MAP and HR compared to control mice, but may also be resistant to hypertensive stimuli such as air-jet stress.

Figure 5.

(A) Changes in mean arterial (MAP), (B) heart rate (HR) and (C) area under curve (AUC) for blood pressure during acute air-jet stress and recovery period in WT (n=5) and LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre (n=6) mice. # p<0.05 compared to WT mice.

Chronic effects of leptin on spontaneous baroreflex sensitivity (BRS) and power spectral analyses of systolic arterial pressure (SAP) and RR interval (RRI) oscillations

Spontaneous BRS were analyzed by time and frequency domains (alpha indexes) during control, after 7 days of leptin infusion and during the recovery period (please see http://hyper.ahajournals.org, Table S1). LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre and WT mice showed similar baseline spontaneous BRS as assessed by the sequence method, and chronic leptin infusion for 7 days did not alter spontaneous BRS in either group (please see http://hyper.ahajournals.org, Table S1).

Spectral analyses data obtained at baseline, day 7 of leptin infusion and day 5 of the recovery period are shown in supplement Table S2. Spectral analyses data of HR and BP oscillations between 0.2 – 0.7 Hz (low frequency region, LF) were used to assess sympathetic modulation whereas oscillations of HR in the high frequency (HF), region, between 0.7 – 2.0 Hz were used to assess parasympathetic tone. At baseline, the high frequency range of HR, reflecting the parasympathetic tone to the heart, was slightly higher in LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice compared to WT mice although the difference did not reach statistical significance. The data also suggest that chronic intravenous leptin infusion caused small, but not significant, enhancement of the power of RRI and SAP spectra in the LF range in WT mice compared to baseline (please see http://hyper.ahajournals.org, Table S2). No significant changes in LF or HF components were observed in LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre during chronic leptin infusion or the recovery period.

Effects of chronic leptin infusion on VO2 and motor activity

There were no significant differences in VO2 in LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre and WT at baseline (Figure 6A). Chronic leptin infusion increased VO2 by 21% in LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre and by 15% in WT mice (Figure 6A). At baseline, no differences in motor activity were observed between groups. Chronic leptin infusion significantly reduced motor activity in both groups (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Response to chronic leptin infusion (2 μg/kg/min) for 7 days on (A) oxygen consumption (VO2) and (B) motor activity in LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre (n=6) and WT (n=5) mice. * p<0.05 compared to control period.

Effects of chronic leptin infusion on plasma glucose, insulin and leptin levels

At baseline, LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice exhibited significantly higher plasma levels of glucose, insulin and leptin (Figure 7). Chronic intravenous leptin infusion increased plasma leptin levels in WT and LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice from 3.5 ± 0.9 to 80.2 ± 8.5 and 9.2 ± 1.0 to 82.2 ± 2.0 ng/ml, respectively (Figure 7C); these elevated leptin levels are similar to those observed in severe obesity.

Figure 7.

(A) Plasma glucose, (B) insulin and (C) leptin levels in WT (n=6) and LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre (n=7) mice during control, 7th day of leptin infusion, and recovery period. # p<0.05 compared to WT mice; * p<0.05 compared to control period.

Leptin infusion in WT mice caused marked reduction in plasma glucose and insulin levels, whereas leptin failed to reduce plasma glucose or insulin levels in LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice (Figures 7A and B). Similar to WT, chronic leptin infusion also reduced plasma glucose and insulin levels in LepRflox/flox and POMC-Cre mice (Supplementary material online Table S3). These results indicate that activation of leptin receptors in POMC neurons plays a key role in whole body glucose homeostasis, and that activation of leptin receptors in POMC neurons appears to be essential for chronic hyperleptinemia to reduce plasma glucose and insulin levels.

DISCUSSION

There are four major findings in this study. First, we demonstrated that leptin receptor deletion in POMC neurons induced only mild early-onset obesity that was associated with several characteristics of metabolic syndrome, including increased visceral fat as well as increased fasting glucose, insulin and leptin levels. Second, acute and chronic leptin infusions caused similar reductions in food intake and increased VO2 in LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice compared to WT, LepRflox/flox and POMC-Cre control mice. Third, despite exhibiting many features of the metabolic syndrome, mice with disruption of leptin signaling in POMC neurons have normal baseline MAP and HR compared to LepRflox/flox control mice, but reduced MAP and HR when compared to WT mice, and were completely resistant to the effects of leptin to cause chronic elevations in MAP and HR. Fourth, the ability of leptin to reduce plasma glucose and insulin levels was completely abolished in LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice.

Our results therefore indicate that activation of leptin receptors on POMC neurons is critical for the chronic actions of leptin on blood pressure and heart rate regulation, as well as on glucose homeostasis. However, leptin receptor activation in POMC neurons, albeit important in baseline control of food intake and body weight regulation, does not appear to play a major role in mediating the appetite suppressant action of leptin when increased to levels comparable to those found in severe obesity. These observations suggest that other areas of the CNS besides POMC neurons may play a key role in mediating the effect of leptin to reduce appetite and to increase VO2. Data from the present study not only support our previous findings demonstrating that CNS melanocortins represent a key link between obesity, metabolic syndrome and the development of hypertension, but also indicate that leptin receptors located in POMC neurons are the primary CNS site for this link.

Role of POMC neuron leptin receptors in regulating energy balance

LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice were heavier after weaning compared to control mice of similar age, suggesting that leptin receptor signaling in POMC neurons contributes to normal regulation of body weight. A previous study by Balthasar et al. also showed that mice lacking leptin receptors in POMC neurons are mildly obese20. These authors observed no differences in whole body oxygen consumption or food intake in young mice at 10 to 14 weeks of age20. In the present study, we also observed that these mice did not exhibit significant differences in VO2 and energy expenditure compared to control mice at 22 to 24 weeks of age. However, we did observe a small, but significantly higher daily food intake in LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice compared to control mice. This suggests that disruption of leptin receptor signaling in POMC neurons may cause mild obesity mainly due to increased appetite rather than reduced metabolic rate.

The slight hyperphagia and mild obese phenotype of LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice could be interpreted as a contradiction to our observation that both acute and chronic anorexigenic effects of leptin are preserved in these animals. One potential explanation for these observations is that the acute and long-term actions of leptin to regulate appetite depend on activation of leptin receptors in several areas of the CNS but the contribution of POMC neurons, although small, is important for normal regulation of appetite and body weight. Previous studies are consistent with the present study and suggest that the anorexigenic actions of leptin may be, at least in part, independent of the CNS melanocortin system22,23. We and others, however, have demonstrated that pharmacological blockade of MC4R abolishes most of the effects of exogenous leptin to reduce food intake24,28 and that the anorexic effects of leptin are reduced in MC4R deficient mice12. Taken together, these observations are consistent with the following possibilities: 1) functional MC4R are required for leptin to reduce appetite, regardless of whether POMC neurons are activated by leptin; 2) leptin may regulate activity of MC4R and POMC neurons indirectly via activation of leptin receptors in other neurons that send projections to POMC neurons or MC4R expressing neurons. It is also unclear if the absence of leptin receptors in POMC neurons alters the release of other neuropeptides that could contribute to the regulation of food intake, such as cocaine-amphetamine related peptide (CART) and glutamate29,30, which could explain at least part of the mild obesity observed in LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice.

Role of POMC neuron leptin receptors in regulating blood pressure and heart rate

In addition to reducing food intake, chronic leptin infusion in rodents also raises MAP and HR mainly via activation of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS)18,24. The stimulatory effect of leptin on SNS activity appears to be mediated in large part by activation of the POMC-MC4R axis. This concept is supported by our current study which shows that leptin receptor deletion in POMC neurons abolished the chronic effects of leptin on MAP and HR and by previous studies in which acute and chronic blockade of MC4R prevented leptin-induced increases in renal SNS activity, arterial pressure and HR24.

The CNS POMC-MC4R pathway also appears to be an important link between obesity and hypertension. Despite severe obesity, hyperleptinemia and other features of the metabolic syndrome, MC4R deficient mice and humans with disruption of MC4R signaling are not hypertensive25,31. In the present study we found reduced baseline MAP and HR in mice lacking leptin receptors in POMC neurons compared to control mice. Also, chronic leptin infusion, at a rate designed to achieve plasma levels that mimic those found in severe obesity, caused slow and gradual increases in MAP and HR in WT, LepRflox/flox and POMC-Cre control mice but not in LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice. LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice were also resistant to the blood pressure effects of an acute air-jet stress test compared to WT control mice. These observations suggest that POMC neurons are an important site for mediating the chronic cardiovascular effects of leptin, and may also play a role in normal autonomic pressor responses to stress. Our results, however, do not exclude the possibility that activation of leptin receptors in other neuronal types may also contribute to the cardiovascular effects of leptin.

POMC neurons are located mainly in the arcuate nucleus (ARC) of the hypothalamus and in the nucleus of the tract solitarius (NTS) of the brainstem and these two sets of neurons have been shown to be responsive to leptin32. Therefore it is possible that leptin-mediated activation of POMC neurons located in the ARC and/or in the NTS contribute to the pressor actions of leptin. However, our study was not designed to test which of these two groups of POMC neurons are most important in regulation of blood pressure or whether they act in concert to mediate the cardiovascular effects of leptin.

We also compared spontaneous BRS in LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre and age-matched WT mice using time and frequency domains. We observed that LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice have similar spontaneous BRS as age-matched WT mice and that chronic leptin infusion for 7 consecutive days did not alter BRS despite increasing MAP in WT mice. Spectral analyses of fluctuations in the HR and blood pressure were also used for noninvasive assessment of autonomic control. Using telemetric recordings, our data demonstrated that LF and HF components of blood pressure were similar to those described in previous studies that used frequency domain analysis. Our data indicate a tendency for reduced sympathetic tone at baseline and no increase in sympathetic activity during chronic leptin infusion in LepRflox/flox/POMC-Cre mice, supporting our hypothesis that activation of leptin receptors in POMC neurons is important for leptin-induced elevations in sympathetic activity and arterial pressure.

Role of POMC neuron leptin receptors in glucose homeostasis

Leptin administration markedly enhances peripheral tissue glucose utilization via insulin dependent and independent mechanism16,33. Some of leptin’s effects on tissue glucose utilization may involve local actions of leptin in peripheral tissues (acute effects), but the CNS actions of leptin that, in turn, are transmitted to peripheral tissue also appear to play a major role in stimulating tissue glucose utilization (chronic effects)15,16. Although the precise CNS mechanisms by which leptin regulates peripheral glucose utilization are still unknown, previous studies from our laboratory suggest that a functional MC4R may play an important role33. Our current studies indicate that activation of leptin receptors in POMC neurons is necessary for leptin to reduce insulin and glucose levels, since deletion of leptin receptor in POMC neurons completely abolished these effects of leptin.

In summary, we have demonstrated that leptin’s chronic hypertensive effects as well as its effects on insulin and glucose regulation require activation of leptin receptors in POMC neurons, whereas the anorexigenic and VO2 actions of leptin and its ability to regulate body weight are mediated to a greater extent by leptin receptors located in other neuron populations that may or may not interact with POMC neurons. These observations provide insights into potential pathways by which leptin may differentially regulate blood pressure, glucose homeostasis, VO2 and appetite. Further studies are needed to determine which CNS sites are most important for leptin’s actions on body weight and appetite regulation under normal conditions as well as in obesity which appears to cause “resistance” to the anorexigenic effects of leptin whereas the SNS and hypertensive effects of leptin may be preserved.

PERSPECTIVES

Experimental and clinical studies suggest that obesity and associated metabolic abnormalities are risk factors for the development of chronic cardiovascular diseases. Our laboratory and others have shown that leptin is an important link for excess weight gain to raise SNS activity and blood pressure. In the present study we demonstrated that activation of leptin receptors in POMC neurons is necessary for the chronic actions of leptin to increase blood pressure and heart rate, as well as to improve glucose regulation. In addition, our results also suggest that activation of leptin receptors in other areas of the CNS besides POMC neurons appear to mediate the effects of leptin on appetite and energy expenditure. Taken together these observations may help explain the paradox of the apparent impairment of leptin’s ability to regulate body weight in obesity while at the same time its ability to raise SNS activity and blood pressure is preserved. The mechanisms that contribute to this differential control of appetite and cardiovascular function by leptin are still not completely understood and remain an important area for future investigations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Haiyan Zhang for the insulin and leptin assays, and Benjamin Pace and John Rushing for the mouse breeding and genotyping.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This research was supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Grant PO1HL-51971 and by the American Heart Association.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST/DISCLOSURES

None.

References

- 1.Spiegelman BM, Flier JS. Obesity and the regulation of energy balance. Cell. 2001;104:531–543. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00240-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harris RB. Leptin-much more than a satiety signal. Annu Rev Nutr. 2000;20:45–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.20.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Badman MK, Flier JS. The gut and energy balance: visceral allies in the obesity wars. Science. 2005;307:1909–1914. doi: 10.1126/science.1109951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bjorbaek C, Kahn BB. Leptin signaling in the central nervous system and the periphery. Recent Prog Horm Res. 2004;59:305–331. doi: 10.1210/rp.59.1.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chua SC, Jr, Chung WK, Wu-Peng XS, Zhang Y, Liu S-M, Tartaglia L, Leibel RL. Phenotypes of mouse diabetes and rat fatty due to mutations in the OB (leptin) receptor. Science. 1996;271:994–996. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5251.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee G-H, Proenca R, Montez JM, Carroll KM, Darvishzadeh JG, Lee JI, Friedman JM. Abnormal splicing of the leptin receptor in diabetic mice. Nature. 1996;379:632–635. doi: 10.1038/379632a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen H, Charlat O, Tartaglia LA, Woolf EA, Weng X, Ellis SJ, Lakey ND, Culpepper J, More KJ, Breitbart RE. Evidence that the diabetes gene encodes the leptin receptor gene in db/db mice. Cell. 1996;84:491–495. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81294-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y, Proenca R, Maffei M, Barone M, Leopold L, Friedman JM. Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue. Nature. 1994;372:425–432. doi: 10.1038/372425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tartaglia LA, Dembski M, Weng X, Deng N, Culpepper J, Devos R, Richards GJ, Campfield LA, Clark FT, Deeds J. Identification and expression cloning of a leptin receptors, OB-R. Cell. 1995;83:1263–1271. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90151-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scarpace PJ, Matheny M, Zhang Y, Tumer N, Frase CD, Shek EW, Hong B, Prima V, Zolotukhin S. Central leptin gene delivery evokes persistent leptin signal transductions in young and aged-obese rats but physiological responses become attenuated over time in aged-obese rats. Neuropharmacology. 2002;42:548–561. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campfield LA, Smith FJ, Guisez Y, Devos R, Burn P. Recombinant mouse OB protein: evidence for a peripheral signal linking adiposity and central neural networks. Science. 1995;269:546–549. doi: 10.1126/science.7624778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tallam LS, da Silva AA, Hall JE. Melanocortin-4 receptor mediates chronic cardiovascular and metabolic actions of leptin. Hypertension. 2006;48:58–64. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000227966.36744.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haynes WG, Morgan DA, Walsh SA, Mark AL, Sivitz W. Receptor-mediated regional sympathetic nerve activation by leptin. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:270–278. doi: 10.1172/JCI119532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chong AY, Lupsa BC, Cochran EK, Gorden P. Efficacy of leptin therapy in the different forms of human lipodystrophy. Diabetologia. 2010;53:27–35. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1502-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.da Silva AA, Tallam LS, Liu J, Hall JE. Chronic antidiabetic and cardiovascular actions of leptin: role of CNS and increased adrenergic activity. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;291:R1275–R1282. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00187.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.do Carmo JM, Hall JE, da Silva AA. Chronic central leptin infusion restores cardiac sympathetic-vagal balance and baroreflex sensitivity in diabetic rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;297:R803–R812. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00265.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hall JE, da Silva AA, do Carmo JM, Dubinion J, Hamza S, Munusamy S, Smith G, Stec DE. Obesity-induced hypertension: Role of sympathetic nervous system, leptin and melanocortins. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:17271–17276. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.113175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carlyle M, Jones OB, Kuo JJ, Hall JE. Chronic cardiovascular and renal actions of leptin: role of adrenergic activity. Hypertension. 2002;39:496–501. doi: 10.1161/hy0202.104398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mountjoy KG, Robbins LS, Mortrud MT, Cone RD. The cloning of a family of genes that encode the melanocortin receptors. Science. 1992;257:1248–1251. doi: 10.1126/science.1325670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baltasar N, Coppari R, McMinn J, Liu SM, Lee CE, Tang V, Kenny CD, McGovern RA, Chua SC, Elmquist JK, Low BB. Leptin receptor signaling in POMC neurons is required for normal body weight homeostasis. Neuron. 2004;42:983–991. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Rienzo M, Parati G, Castiglioni P, Tordi R, Mancia G, Pedotti A. Baroreflex effectiveness index: an additional measure of baroreflex control of heart rate in daily life. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;280:R744–R751. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.280.3.R744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Challis BG, Coll AP, Yeo GS, Pinnock SB, Dickson SL, Thresher RR, Dixon J, Zahn D, Rochford JJ, White A. Mice lacking pro-opiomelanocortin are sensitive to high-fat feeding but respond normally to the acute anorectic effects of peptide-YY3-36. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:4695–4700. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306931101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marsh DJ, Hollopeter G, Huszar D, Laufer R, Yagaloff KA, Fisher SL, Burn P, Palmiter RD. Response of melanocortin-4 receptor deficient mice to anorectic and orexigenic peptides. Nat Genet. 1999;21:119–122. doi: 10.1038/5070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.da Silva, Kuo JJ, Hall JE. Role of hypothalamic melanocortin3/4 receptors in mediating chronic cardiovascular, renal and metabolic actions of leptin. Hypertension. 2004;43:1312–1317. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000128421.23499.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tallam LS, Stec DE, Willis MA, da Silva AA, Hall JE. Melaonocortin-4 receptor-deficient mice are not hypertensive or salt-sensitive despite obesity, hyperinsulinemia and hyperleptinemia. Hypertension. 2005;46:326–332. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000175474.99326.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cowley MA, Smart JL, Rubinstein M, Cerdan MG, Diano S, Horvath TL, Cone RD, Low MJ. Leptin activates anorexigenic POMC neurons through a neural network in the arcuate nucleus. Nature. 2001;411:480–484. doi: 10.1038/35078085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baudrie V, Laude D, Elghozi JL. Optimal frequency ranges for extracting information on cardiovascular autonomic control from blood pressure and pulse interval spectrograms in mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;292:R904–R912. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00488.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seeley RJ, Yagaloff KA, Fisher SL, Burn P, Thiele TE, Van Dijk G, Baskin DG, Schwart MW. Melanocortin receptors in leptin effects. Nature. 1997;390:349. doi: 10.1038/37016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elias CF, Lee C, Kelly J, Aschkenasi C, Ahima RS, Couceyro PR, Kuhar MJ, Saper CB, Elmquist JK. Leptin activates hypothalamic CART neurons projecting to the spinal cord. Neuron. 1998;21:1375–1385. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80656-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Collin M, Backberg M, Ovesjo ML, Fisone G, Edwards RH, Fujiyama F, Meister B. Plasma membrane and vesicular glutamate transporter mRNAs/proteins in hypothalamic neurons that regulate body weight. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;8:1265–1278. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vaisse C, Clement K, Guy-Grand B, Froguel P. A frameshift mutation in human MC4R is associated with a dominant form of obesity. Nat Genet. 1998;20:113–114. doi: 10.1038/2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scott MM, Lachey JL, Sternson SM, Lee CE, Elias CF, Friedman JM, Elmquist JK. Leptin targets in the mouse brain. J Comp Neurol. 2009;514:518–532. doi: 10.1002/cne.22025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.da Silva AA, do Carmo JM, Freeman JN, Tallam LS, Hall JE. A functional melanocortin system may be required for chronic CNS-mediated antidiabetic and cardiovascular actions of leptin. Diabetes. 2009;58:1749–1756. doi: 10.2337/db08-1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.