Abstract

The purpose of this study was to examine pathways in a model which proposed associations among parent mindfulness, parent depressive symptoms, two types of parenting, and child problem behavior. Participants’ data were from the baseline assessment of a NIMH-sponsored Family-Group Cognitive-Behavioral intervention program (FGCB) for the prevention of child and adolescent depression (Compas et al., 2009). Participants consisted of 145 mothers and 17 fathers (mean age = 41.89 yrs, SD = 7.73) with a history of depression and 211 children (106 males) (mean age = 11.49 yrs, SD = 2.00). Analyses showed that (a) positive parenting appears to play a significant role in helping explain how parent depressive symptoms relate to child externalizing problems and (b) mindfulness is related to child internalizing and externalizing problems; however, the intervening constructs examined did not appear to help explain the mindfulness-child problem behavior associations. Suggestions for future research on parent mindfulness and child problem outcome are described.

Keywords: Parent mindfulness, parenting, parent depressive symptoms, child problem behaviors

Introduction

Mindfulness has received significant attention in different fields of psychology and medicine but is only beginning to receive attention in research with children and families (Dumas, 2005). Mindfulness is defined as “the awareness that emerges through paying attention on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally to the unfolding of experience moment by moment” (Kabat-Zinn, 1994, p. 4). Thoughts as events without judgment allow one to differentiate between one’s perception and one’s response. In turn, this differentiation allows an individual to act with intention rather than react automatically (Bishop et al., 2004). Theoretically, mindfulness practice over time may lead to greater cognitive complexity and increased emotional awareness because of an increased ability to draw distinctions between separate cognitive and affective experiences (Bishop et al., 2004).

Mindfulness has been associated with reduction in ruminative thinking (Kingston, Dooley, Bates, Lawlor, & Malone, 2007) by allowing one to disengage from an automatic train of thought and focus on the present moment (Bishop et al., 2004). Mindfulness has been examined as a treatment for depression, as ruminative thinking has been proposed to play an important role in depression (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1998; Roelofs et al., 2009; Segal, Williams, & Teasdale, 2002; Teasdale, 1988). A recent meta-analytic review found that mindfulness-based therapy is associated with reductions in depressive symptoms at both post-intervention and follow-up assessments (Hofmann, Sawyer, Witt, & Oh, 2010).

Although there is research demonstrating the role of mindfulness in adult depression, there is an absence of studies examining the association of mindfulness and depression in samples of depressed parents. Parental depression is an important area of study because it affects not only parents, but also offspring (Burke, 2003; Goodman, 2007). It is estimated that at least 15 million children live in households with parents who are depressed (National Research Council & Institute of Medicine, 2009), and rates of depression among children of depressed parents have ranged from 20% to 41% (Goodman, 2007). If mindfulness relates to depressive symptoms among parents with a history of depression, then examining this construct may elucidate how parental depression operates within families.

Parents who are depressed contribute to their children’s psychopathology in part through their parenting behavior (Goodman & Gotlib, 1999). Research on parental depression and parenting shows that depressed parents use more negative (e.g., parental negative affect, hostility, intrusiveness, neglect/distancing) and less positive (e.g., warmth, child-centered behaviors, positive reinforcement, quality time, child monitoring) parenting behaviors (Dix & Meunier, 2009; Lovejoy, Graczyk, O’Hare, & Neuman, 2000). Furthermore, when parenting behaviors of parents with a history of depression are changed through a family cognitive behavioral program, this change is associated with reduction in some indicators of child internalizing and externalizing problems (Compas et al., 2010). Such findings provide support for the role of parenting in children’s problem behavior in families with a depressed parent.

Despite the evidence indicating that mindfulness is related to depression and that depression is related to both parenting behaviors and child problem behavior, the role of mindfulness in parenting and children’s problem behaviors is limited. In a theoretical paper that outlined how parent mindfulness training could modify automaticity of maladaptive parenting interactions, Dumas (2005) conceptualized parent mindfulness training as a means for parents to “consider their own and their child’s behavior nonjudgmentally, to distance themselves from negative emotions and develop parenting goals” (p. 780). More recently, Duncan, Coatsworth, and Greenberg (2009) have suggested that parents who are more mindful have an enhanced capacity for parenting calmly and with greater consistency.

Recently, several investigators have begun to examine the role of parents’ mindfulness in child problem behaviors. Coatsworth, Duncan, Greenberg, and Nix (2010) found that the addition of a mindful parenting program enhanced a few aspects of the parent-adolescent relationship beyond those achieved with a standard parent-adolescent intervention. Singh and his colleagues (Singh et al., 2006; Singh et al., 2007; Singh, Lancioni et al., 2010; Singh, Singh et al., 2010) reported in a series of single-subject design studies that mindfulness training for parents is associated with decreases in child aggression and noncompliance as well as parents’ reported satisfaction with their new parenting skills. In summary, implementation of mindfulness-based interventions has been shown to be associated with reductions in adult depressive symptoms (Hofmann et al., 2010), has been proposed to relate to parenting (e.g., Dumas, 2005), and in single-subject research (e.g., Singh, Lancioni et al., 2010) and one group study (Coatsworth et al., 2010) has been found to relate to child problem behavior.

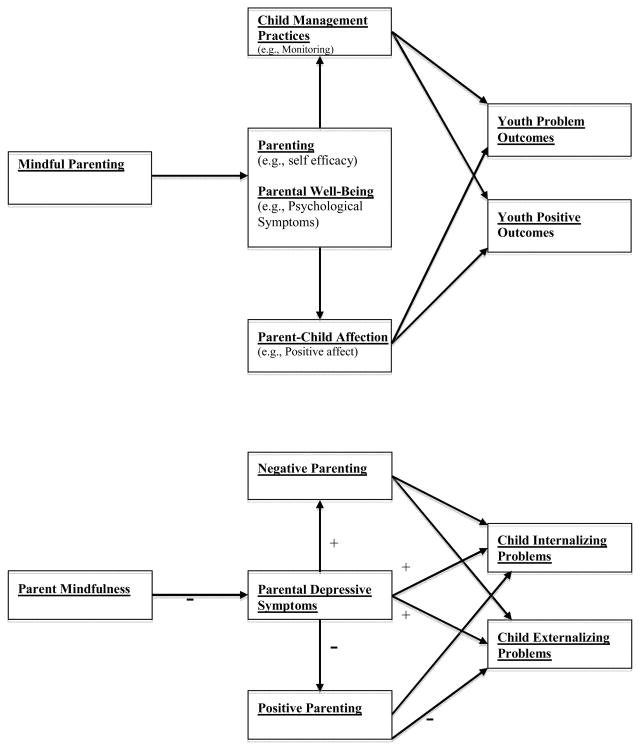

Duncan et al. (2009) proposed a conceptual model linking mindful parenting, parent well-being (e.g., fewer psychological symptoms), parenting, and child outcome (see Figure 1, top model). Congruent with Duncan et al.. (2009), Cohen and Semple (2010) have called for research investigating the effects of mindfulness on parental depressive symptoms, parenting, and child outcome in families with a depressed parent. Building on Duncan et al.’s (2009) model and Cohen and Semple’s (2010) call for research, we test the pathways in a model similar to the one proposed by Duncan et al.

Figure 1.

Duncan et al. (2009a) proposed model (top) and model tested in current study (bottom). Proposed significant pathways are marked in the bottom model by positive (+) and negative (−) signs to indicate the direction of the association.

The Duncan et al. (2009) conceptual model delineates associations of mindful parenting with general parenting (e.g., self-efficacy) and parental well-being (i.e., psychological symptoms) that, in turn, relate to child outcomes through two specific parenting practices: affection and child management. The Duncan et al. model was modified in the following ways in the current study: (a) Parent mindfulness (e.g., listening with full attention, nonjudgmental acceptance) was examined rather than mindful parenting (e.g., listening to the child with full attention, nonjudgmental acceptance of self and child, emotional awareness of self and child, self-regulation in the parenting relationship, and compassion for self and child) in order to differentiate general mindfulness from more specific parenting skills which are examined in subsequent aspects of the model; (b) positive and negative parenting were examined instead of child-management practices and parent-child affection in order to include the assessment of negative parenting, which is associated with child problem behavior (see McMahon, Wells, & Kotler, 2006, for a review); (c) associations between the indicator of parent well-being (i.e., depressive symptoms) and child outcomes were added (see Figure 1, bottom model) as research with depressed parents provides evidence for these direct pathways (see Goodman, 2007, for a review); and (d) child problem behavior was partitioned into internalizing and externalizing problems in order to examine the differential associations of parental depressive symptoms and parenting with each type of child problem behavior.

Figure 1 (bottom model) delineates the associations examined in the current study. We proposed that parent mindfulness would relate inversely to parental depressive symptoms, which, in turn, would relate positively to negative parenting and negatively to positive parenting. We hypothesized that, when considered simultaneously as predictors of child outcome, parent depressive symptoms would relate directly to child internalizing and externalizing symptoms and indirectly through positive parenting to child externalizing problems. These latter two hypotheses are based on the existing literature with parents who have a history of depression (see Goodman, 2007). Although other pathways were examined to ensure that possible relationships were not overlooked (i.e., negative parenting with child internalizing and externalizing problems), we did not offer hypotheses as the investigation of these pathways were viewed as exploratory.

Methods

Participants

Participants’ data were from the baseline assessment of a Family-Group Cognitive-Behavioral intervention program (FGCB) for the prevention of child and adolescent depression (Compas et al., 2009). The initial sample consisted of 180 families with 242 children (ages 9–15 years) recruited from the areas surrounding Nashville, TN and Burlington, VT. Because of missing data on variables of interest in the current study, 19 of the 180 families initially recruited (including 31 children) were excluded, resulting in the sample of 162 families. In participating families with multiple children in the 9–15 age range (30.9% of sample), all children were included.

The final sample consisted of 145 mothers and 17 fathers (mean age = 41.89 yrs, SD = 7.73), and 211 children (106 males) (mean age = 11.49 yrs, SD = 2.00). Parents were largely Caucasian (81.5%), well educated (85.9% reported at least some college), and married or living with a partner (61.1%) (see Table 1 for further demographic information).

Table 1.

Descriptive Data for Demographic Variables

| Dependent Variable | M (SD) | Percentages |

|---|---|---|

| Child’s age | 11.49 (2.00) | -- |

| Childs Gender | ||

| Boys | -- | 50.2% |

| Girls | -- | 49.8% |

| Target Parent’s Age | 41.89 (7.73) | -- |

| Target Parent’s Gender | ||

| Mother | -- | 89.5% |

| Father | -- | 10.5% |

| Target Parent’s Martial Status | ||

| Married/Living with partner | -- | 61.1% |

| Single | -- | 38.9% |

| Child’s Race | ||

| Caucasian/ not Hispanic | -- | 72% |

| Minority | -- | 28% |

| Target Parent’s Education Level | ||

| Less than high school | -- | 5.6% |

| High school (or equivalency exam) | -- | 8.6% |

| Some college or technical school (At least 1 year) | -- | 30.9% |

| College graduate (4 year degree) | -- | 30.9% |

| Graduate education (Anything beyond 4 year degree) | -- | 24.1% |

| Household Income | ||

| Under $5,000 | -- | 7.1% |

| $5,000–9,999 | -- | 3.9% |

| $10,000–14,999 | -- | 1.9% |

| $15,000–24,999 | -- | 11.0% |

| $25,000–39,999 | -- | 20.6% |

| $40,000–59,999 | -- | 17.4% |

| $60,000–89,999 | -- | 20.6% |

| $90,000–179,999 | -- | 14.2% |

| Over $180,000 | -- | 3.2% |

Eligibility Criteria

The criteria for a family’s inclusion were a parental history of MDD or dysthymia within the child’s lifetime and a GAF (Global Assessment of Functioning) over 50. The criteria for family exclusion were: (1) parental history of bipolar I, schizophrenia, or schizoaffective disorders; (2) any participating child who had a history of autism spectrum disorder or mental retardation, bipolar I disorder, or schizophrenia disorder; or (3) any participating child who met criteria for current conduct disorder or substance/alcohol abuse or dependence. Families were temporarily excluded, but and re-assessed every two-months, if any participating child met criteria for current MDD or if a parent had a GAF under 50.

Measures

Screening Measures

Parent eligibility was determined via the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2002). The SCID-I was initially used to screen parents for a history of MDD during the target child’s lifetime. Adequate reliability and validity have been demonstrated for the SCID-I. For example, for MDD, kappas have ranged from .61 (Zanarini et al., 2000) to .93 (Skre, Onstad, Torgersen, & Kringlen, 1991). In the current study, inter-rater reliability, calculated on a randomly selected subset of interviews, indicated 93% agreement (kappa = .71) for diagnoses of MDD.

Child eligibility was determined by the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-aged Children - Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL; Kaufman, et al., 1997), a semi-structured interview designed to ascertain present episode and lifetime history of psychiatric illness according to DSM-IV criteria. Reliability and validity have been established and are adequate (Kaufman et al., 1997). In the current study, inter-rater reliability, calculated on a randomly selected subset of interviewers indicated 96% agreement (kappa = .76) for MDD diagnosis.

Demographic Information

Demographic variables (parental age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, level of education, household income, child age, child race and gender) were reported by the parent on a demographic questionnaire.

Parent Depressive Symptoms

The Beck Depression Inventory, Second Edition (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996), was used to assess current levels of parental depressive symptoms. Participants responded to 21 items in which they chose the statement that best described the way they felt in the previous two weeks. Statements were rated on a 4-point Likert scale (e.g., 0 = “I do not feel sad”, 1 = “I feel sad much of the time”, 2 = “I am sad all the time” and 3 = “I am so sad or unhappy that I can’t stand it”). Higher scores reflect more depressive symptoms over the past two weeks. The BDI-II has shown excellent internal consistency (α = .92) and correlates highly with other measures of depression (r = .93) (Beck, Steer, Ball, et al., 1996). Suggested categories for the BDI-II include: 0–13 = minimal depression; 14–19 = mild depression; 20–28 = moderate depression; and 29–63 = severe depression (Beck et al., 1996). The alpha coefficient for the current sample was .93.

Mindfulness

Parents completed the 15-item Mindfulness Attention and Awareness Scale (MAAS; Brown & Ryan, 2003). The MAAS is a scale that reflects a respondent’s global experience of mindfulness in addition to specific daily experiences that include “…awareness of and attention to actions, interpersonal communication, thoughts, emotions, and physical states” (Brown & Ryan, 2003, p. 825). Participants indicated how frequently they had the experience described in each statement (e.g., “I rush through activities without being really attentive to them” and “I find it difficult to stay focused on what’s happening in the present.”) Statements were scored on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (almost always) to 6 (almost never). Higher scores reflect higher levels of mindfulness. The MAAS has good internal consistency (α = .80–.90) across a wide range of samples (e.g., Brown & Ryan, 2003; MacKillop & Anderson, 2007). The alpha coefficient for the current sample was .89.

Observations of Parenting

The Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales (IFIRS; Melby, Conger et al., 1998) was used to code positive and negative parenting in two videotaped 15-minute conversations. The first conversation consisted of a recent pleasant activity that the parent and child enjoyed doing together. The second conversation consisted of a stressful time when the parent was depressed, down, or grouchy, which, in turn, made it difficult for the family. The IFIRS is a global coding system used to measure behavioral and emotional characteristics at both the individual and dyadic level. Each behavior is coded on a 9-point scale (1 = “not at all characteristic” to 9 = “mainly characteristic”). In order to determine the score for each code, frequency and intensity of the behavior, along with the contextual and affective nature of the behavior, are considered. Validity of the IFIRS has been established using correlational and confirmatory analyses (Aldefer et al., 2008; Melby & Conger, 2001).

Training on the IFIRS consisted of in-depth studying of the manual, a written test of the scale definitions, and establishment of inter-rater reliability. Successful completion of training consisted of passing a written test with at least 90% correct, and achieving at least 80% reliability on observational tests. Weekly training meetings also were held to prevent coder drift.

Interactions were double-coded by two independent coders. If the coders scored a behavior code more then 2 points apart on the 9-point scale, coders met to reach a consensus. Once consensus was reached, scores were averaged across the two 15-minute tasks described above and then composite codes were created for positive and negative parenting by combining behaviors that fit into each of these two constructs. The positive parenting composite included parents’ warmth, child-centered behaviors, positive reinforcement, quality time, listener responsiveness, and child monitoring. The negative parenting composite included parental negative affect, hostility, intrusiveness, neglect/distancing, and externalize negative.

Child Internalizing and Externalizing Problems

The Child Behavior Checklist for Ages 6–18 (CBCL/6–18; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) and Youth Self-Report for Ages 11–18 (YSR/11–18; Achenbach & Rescorla) were used to measure child internalizing and externalizing problems from both parent and child report. Both instruments consist of 118-items that assess child behavioral and emotional problems over the last six months. The CBCL/6–18 and YSR/11–18 each yield two broadband factors, internalizing and externalizing, both of which was used in the current study.

On both the CBCL and the YSR the child’s behavior was rated on a 3-point Likert scale with 0 being “not true”, 1 being “somewhat or sometimes true”, and 2 being “very true or often true.” Reliability and validity of the CBCL and YSR are well established (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). The alpha coefficient for internalizing problems was .91 (YSR) and .85 (CBCL) and for externalizing problems was .84 (YSR) and .84 (CBCL) for the current sample.

Procedure

Internal review boards at the University of Vermont and Vanderbilt University approved all study procedures. Participants were recruited from mental health agencies, doctor’s offices, hospitals, and by local newspaper and radio advertisements. Prospective participating parents were initially screened via a diagnostic phone interview. If initial eligibility criteria were met, parents and their child(ren) were invited to come to a local university to sign consent and assent forms and take part in a thorough screening assessment. At this in-person assessment, doctoral students in clinical psychology, each of whom had 25 hours of training on each instrument, administered the SCID-I to the parent (SCID-I; First et al., 2002) and the K-SADS-PL (K-SADS-PL; Kaufman et al., 1997) separately to the parent and participating child.

Parents and children also completed self-report questionnaires, these included the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS), and the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL). Children completed the Youth Self Report (YSR) among other measures. Finally, the parent-child dyad participated in two 15-minute videotaped interactions that occurred in a private, confidential laboratory space and followed a similar research protocol (described in measures) to that used in previous studies (e.g., Jaser et al., 2008). Families were compensated for their participation in the baseline phase of the study ($40 per participating child and $40 per target parent).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Five sets of preliminary analyses were conducted. First, parents and children with complete data were compared to those with missing data (and thus excluded from the current sample) on demographic variables. Second, descriptive statistics were generated for the main study variables. Third, the correlation between parent and child report on internalizing problems and on externalizing problems was examined. Fourth, the relations between continuous demographic variables (i.e., SES and child age) and the outcome variables (i.e., child internalizing and externalizing problems) were examined. Because of the nested nature of the data (i.e., multiple children in some families), correlations were computed after individual cases were weighted. For example, when correlating SES and child internalizing problems in a family with two participating children, the value of SES was weighted at one-half. One-way analyses of variance, also weighted to account for multiple children in families, were used to examine the relation between dichotomous variables (i.e., child gender, child race and parent marital status) and the outcome variables (i.e., child internalizing and externalizing problems). Fifth, weighted correlations were conducted among the independent and dependent variables.

Parents and children with complete data did not differ on demographic variables from those with missing data. The means, standard deviations, and ranges for each of the main study variables are presented in Table 2. The mean BDI-II score for parents was 19.28 (SD = 12.06), which suggests that, on average, parents reported depressive symptoms in the mild to moderate level of severity. The total score mean on the MAAS was 55.12 (SD = 14.34) which is above the median possible score on the scale. Although raw scores were used in analyses, T scores were calculated for child internalizing and externalizing problems to compare the current sample to the normative sample. Average T scores for internalizing problems were 54.14 (YSR) and 59.27 (CBCL), and average T scores for externalizing problems were 49.55 (YSR) and 54.50 (CBCL), all of which fell in the normative range. The sample of children can be characterized as at-risk based on moderately elevated mean T scores for all measures except the YSR externalizing problem scale. Specifically, the percentage of children in the clinical range for the internalizing scale (i.e., T score > 63) was 23.6% on the YSR and 43.5% on the CBCL; the percentage for the externalizing scale (i.e., T score > 63) was 10.6% on the YSR and 22.5% on the CBCL.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for Primary Variables

| Variable | M (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|

| CBCL1 | ||

| Internalizing raw score | 11.59 (7.47) | 0–32 |

| Externalizing raw score | 9.72 (8.18) | 0–46 |

| YSR2 | ||

| Internalizing raw score | 13.27 (9.58) | 0–44 |

| Externalizing raw score | 9.61 (7.26) | 0–37 |

| Parenting | ||

| Observed Positive Parenting | 27.60 (5.14) | 16–38 |

| Observed Negative Parenting | 24.02 (5.52) | 13–39 |

| Parent Depressive Symptoms3 | ||

| BDI-II | 19.28 (12.06) | 0–48 |

| Parent Mindfulness4 | ||

| MAAS | 55.12 (14.34) | 22–90 |

Note.

Parent Report; raw score (possible range 0 – 70)

Child Report; raw score (possible range 0 – 64)

Beck Depression Inventory Second Edition (BDI-II); total score (possible range 0 – 63)

Mindful Attention and Awareness Scale (MAAS); total score (possible range 15–90)

As both parent report (CBCL) and child report (YSR) of child internalizing and externalizing problems were collected, a weighted correlation was computed between the YSR and CBCL on each of the two scales examined (internalizing and externalizing scores) to determine if they could be combined. A significant correlation was found for internalizing (r = .36, p < .001) and externalizing (r = .47, p < .001) problems; therefore, the reports of parent and child were standardized (z-scores) and summed to form a multiple reporter construct for each of the problem behaviors.

The relations of each of the demographic variables (see Table 1) with child internalizing and externalizing problems were examined. Prior to these analyses, three of the demographic variables were adjusted. Parent marital status was transformed into a two category variable (1 = Second parent or partner lived in the home; 2 = Second parent or partner did not live in home); child race was also transformed into a two category variable (1 = Caucasian/non-Hispanic; 2 = not Caucasian/non-Hispanic) due to low frequency of children identifying with a race other than Caucasian/non-Hispanic; and parent education level and household income, which were significantly correlated (r = .39, p < .001), were standardized and combined to form a measure of family socioeconomic status (SES) (Ensminger & Forthergill, 2003).

Significant effects emerged for two of the dichotomous demographic variables for both child internalizing and externalizing problems; parent marital status (internalizing, F (1) = 10.87, p < .001; externalizing, F (1) = 5.32, p < .05), and child race (internalizing, F (1) = 16.23, p < .01; externalizing, F (1) = 15.47, p < .01). Children who had two parents living in the home and who were Caucasian/non-Hispanic had fewer internalizing and externalizing problems than those who had only one parent living in the home and who were not Caucasian/non-Hispanic. Of the continuous demographic variables, only family socioeconomic status was significantly related to child internalizing (r = −.20, p < .001) and externalizing (r = −.18, p < .01) problems. Thus, the above three demographic variables were controlled when child internalizing and externalizing problems served as the dependent variable.

When associations among study variables were examined, parent mindfulness was significantly negatively correlated with parental depressive symptoms (r = −.36, p < .01), child internalizing problems (r = −.21, p < .01) and child externalizing problems (r = −.16, p < .05) but not with observed positive (r = −.01, ns) or negative (r = −.05, ns) parenting. Parental depressive symptoms were significantly and inversely related to observed positive parenting (r = −.34, p < .001) and positively related to observed negative parenting (r = .36, p < .001) as well as child internalizing (r = .27, p < .001) and externalizing (r = .24, p < .001) problems. Observed positive parenting was significantly negatively related to both child internalizing (r = −.20, p < .001) and externalizing (r = −.32, p < .001) problems. Observed negative parenting also was significantly positively related to both child internalizing (r = .24, p < .001) and externalizing (r = .29, p < .001) problems.

Primary Analyses

To examine the associations in the model in Figure 1 (bottom), two types of analyses were performed based on whether these associations were comparable for multiple children from the same family. For the pathway from parent mindfulness to parent depressive symptoms, a hierarchical linear regression was conducted. For the remaining pathways, each of which involved parenting with multiple children in the same family or problem behavior of multiple children in the same family, two-level Linear Mixed Models (LMM) analyses were conducted. Level 1 of a LMM represents observations at the individual level including child internalizing and externalizing problems. Level 2 of a LMM denotes clusters of units within the dataset such as parental depressive symptoms and observed positive and negative parenting that maintain a constant relationship across all children within the same family.

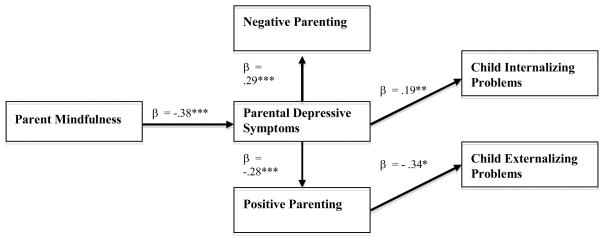

The significant associations are depicted in Figure 2. Higher levels of parent mindfulness were associated with lower levels of parent depressive symptoms (β =−.38, p < .001). Higher levels of parent depressive symptoms were associated with lower levels of positive parenting (β =−.28, p < .001) and higher levels of negative parenting (β = .29, p < .001). After controlling for demographic variables, parent depressive symptoms (β = .19, p < .01), but not observed positive (β = .01, ns) or observed negative parenting (β = .12, ns), were significantly associated with child internalizing problems when all three variables were entered simultaneously. After controlling for demographic variables, observed positive parenting (β =− .34, p < .05), but not observed negative parenting (β = .08, ns) or parental depressive symptoms (β = .11, ns), was significantly associated with child externalizing problems when all three variables were entered simultaneously.

Figure 2.

Significant pathways among variables in the proposed model

Note: * = p < .05, ** = p < .01, *** = p < .001

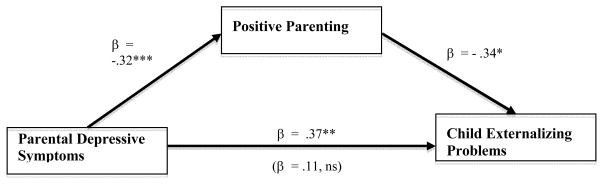

Follow-up analyses were conducted to explore two indirect relationships in the model. First, the correlational analyses indicated that parent depressive symptoms related to child externalizing problems. The significant links in the model between parent depressive symptoms and positive parenting and between positive parenting and child externalizing problems suggest that positive parenting may explain this relationship. The significant relationship between parental depressive symptoms and child externalizing problems (β = .34, p < .05) was reduced when positive parenting was entered into the regression equation (β = .11, ns). To test the significance of the identified indirect effect of parental depressive symptoms on child externalizing symptoms via positive parenting, the Sobel (1982) test was used. Results of the Sobel test revealed that the indirect effect of positive parenting did account for the relationship between parental depressive symptoms and child externalizing problems as the beta weight was significantly reduced (p < .05). The indirect effect model is displayed in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Results of a model testing an indirect effect between parental depressive symptoms and child externalizing problems through positive parenting. The association of parental depressive symptoms with child externalizing problems after entry of positive parenting is indicated in parentheses.

Note: * = p < .05, ** = p < .01, *** = p < .001

Second, the correlational analyses also indicated that parent mindfulness is related to child internalizing problems. The significant links in the model between parent mindfulness and parent depressive symptoms and between parent depressive symptoms and child internalizing problems suggest that parent depressive symptoms may explain this relationship. However, the significant relationship between parental mindfulness and internalizing problems (β =−.25, p < .001) was reduced but still significant (β =− .20, p < .01) when parental depressive symptoms were entered into the regression equation. In order to see if the reduction in beta weight was significant, the Sobel (1982) test was used. Results indicated that the inclusion of parental depressive symptoms reduced the beta weight to a level approaching significance (p = .06).

Discussion

The purpose of the current study was to test the pathways in a model which proposes associations among parent mindfulness, parent depressive symptoms, two types of parenting, and child problem behavior. Families that had a parent with a history of depression were studied. Lower levels of mindfulness among parents were associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms, which, in turn, were related to more negative parenting behaviors and less positive parenting behaviors. Additionally, higher levels of parental depressive symptoms were associated with higher levels of child internalizing problems and higher levels of positive parenting were associated with lower levels of child externalizing problems. The roles of parent depressive symptoms and positive parenting were examined as possible explanatory variables in the model with support emerging for positive parenting explaining the link between parent depressive symptoms and child externalizing problems.

Findings from the current study replicate research showing a negative relationship between mindfulness and depressive symptoms (e.g., Brown & Ryan, 2003). Teasdale (1988) proposed that depressed moods reactivate thinking styles associated with previous depressed moods, creating a self-perpetuating pattern of negative thinking (e.g., ruminative thinking). Higher levels of mindfulness may allow one to become aware of these cognitive processes and then learn and apply mindfulness strategies (e.g., awareness/mindfulness of thoughts, emotions, and bodily sensations, being in the moment, acceptance, and letting go) to disengage from these self-perpetuating patterns (Segal et al., 2002), leading to reductions in depressive symptoms (Hofmann et al., 2010). The current study extended prior research on mindfulness and depressive symptoms to parents with a history of depression, their parenting and their children’s problem outcomes.

Although there were associations of parental mindfulness with both parent depressive symptoms and child internalizing problems, analyses provided minimal support for depressive symptoms explaining the link between parental mindfulness and child internalizing problems. Specifically, when depressive symptoms were entered into the regression equation, the relation between parental mindfulness and child internalizing problems was reduced; however, the relation remained significant with the inclusion of parental depressive symptoms and the Sobel test suggested the reduction in the beta weight approached significance. Furthermore, correlational analyses indicated that mindfulness did not relate to either positive or negative parenting. In combination, these findings suggest that explanations beyond the parent’s well-being as measured by depressive symptoms and parenting as assessed by observations of parent-child interactions need to be considered for explaining how parent mindfulness relates to child internalizing problems. For example, indicators of well-being other than depressive symptoms (e.g., emotional regulation skills, adaptive coping skills) may be informative constructs to consider in future research. Or, alternate assessment strategies (e.g., questionnaires) or more fine-grained behavioral coding of parenting skills that have been hypothesized to be linked to mindfulness (e.g., shift in awareness of attention to child; Duncan et al., 2009) may be useful.

Correlational analyses also suggested that mindfulness was related to child externalizing problems; however, as mindfulness was not related to positive parenting in the correlational analyses. Therefore, indirect links from mindfulness to child externalizing problems through parent depressive symptoms and positive parenting does not explain this association. As with mindfulness and internalizing problems, examining other indicators of parent well-being or alternative assessment strategies for parenting may help explain the link between mindfulness and child externalizing problems.

When examining associations within the model beyond mindfulness, the current findings suggest positive parenting may be one mechanism through which parent depressive symptoms are linked to child externalizing problems. As parents’ current depressive symptoms increase, research suggests their ability to parent positively decreases (see Dix & Meunier, 2009; Lovejoy et al., 2000). Substantial research indicates that lower levels of positive parenting are associated with higher levels of child externalizing problems (e.g., Forgatch & Patterson, 2010; McMahon et al., 2006). Research in our sample of parents with a history of depression suggests that changes in positive parenting, with implementation of a prevention program, is associated with changes in some indicators of child externalizing (as well as internalizing) problems (Compas et al., in press). As withdrawal and lack of attention to children are primary characteristics of depressed parents (see, Lovejoy et al., 2000), increasing positive parenting may be particularly important when a parent has a history of depression.

The findings from the present study suggest that increases in positive, but not negative, parenting are related to child externalizing problems. Much of the research, particularly treatment outcome research, on parenting has not differentiated between positive and negative parenting (e.g., DeGarmo, Patterson, & Forgatch, 2004; Forgatch, Patterson, DeGarmo, & Beldavs, 2009;). However, recent intervention outcome work has found that changes in positive, but not negative, parenting is associated with change in child externalizing problems (Compas et al., 2010; Gardner et al., 2010). The current findings, based on cross-sectional regression analyses, are congruent with these recent treatment outcome studies. However, it is important to note that our preliminary analyses involving univariate correlations indicated negative parenting is related to child externalizing problems; it is only when considered in the context of positive parenting and parental depressive symptoms that this significant relationship is no longer evident. These findings suggest that both positive and negative parenting are important; however, when considered in the context of each other, increases in positive parenting is more strongly related to child outcome. As we have noted, these findings are similar to those in recent treatment outcome research, suggesting that increasing positive parenting should be a primary target in intervention and prevention programs.

The current findings need to be put in the context of our previous research with this same sample of children living in families with a history of parent depression. First, Rakow et al. (2009 First, Rakow et al. (in press) examined a different measure of negative parenting, use of guilt induction, than used in the present study and found in cross-sectional analyses that this construct was associated with child internalizing problems. This suggests that selected indicators of negative parenting do in fact relate to child internalizing problems. Second, Compas et al. (2010) found when a family-based cognitive behavioral prevention program was implemented, positive parenting mediated change in some indicators of both child externalizing and internalizing problems. In contrast, the current findings suggest that positive parenting was associated with only child externalizing problems. These initially appearing discrepant findings may be explained by the child outcome measures used in the two studies. Compas and colleagues found that change in positive parenting mediated change in a narrowly defined measure of internalizing problems, child depressive symptoms, but not the more broadly defined measure of internalizing problems. Only the latter construct was assessed as an indicator of internalizing in the current study. Thus, when the same measure, broadband internalizing problems, is considered across the two studies, the findings are consistent: positive parenting did not relate to child broadband internalizing problems.

There were several limitations of this study. First, due to the cross-sectional nature of the study, causal relations cannot be tested. Second, generalizability of the findings is limited by sample characteristics-- relatively well-educated, primarily Caucasian participants with a history of depression and exclusion of parents and youth who met diagnostic criteria for selected disorders. Third, the current study limited its examination to parental depressive symptoms, which restricts generalization to other indicators of psychological distress. Finally, the current study only examined one facet of mindfulness: attention and awareness. Baer and her colleagues (2006) have argued that mindfulness is a multi-faceted construct. Different findings may emerge if mindfulness is examined from the multi-facet perspective.

There also were several strengths of the current study. Our study is the first to examine associations of mindfulness, parent depressive symptoms, parenting, and child problem behavior. Additionally, the constructs of interest were examined from multiple informants (parent, child) and methods (observational and questionnaire data). Finally, the current study is the first to examine the relation between parent mindfulness and child outcome in families with a history of depression.

The correlational analyses suggested that mindfulness is related to child internalizing and externalizing problems; however, the intervening constructs we examined, parenting and depressive symptoms, did not appear to help explain these associations. Nevertheless, the initial bivariate associations between mindfulness and child problem behaviors, as well as the association of mindfulness to parent depressive symptoms, suggest mindfulness is a construct deserving further attention in research on parental well-being, parenting, and child problem outcome. Finally, positive parenting appears to play a significant role in helping explain how parent depressive symptoms relate to child externalizing problems.

Contributor Information

Justin Parent, Department of Psychology, University of Vermont, Burlington, VT 05405.

Emily Garai, Department of Psychology, University of Vermont, Burlington, VT 05405.

Rex Forehand, Email: Rex.Forehand@uvm.edu, Department of Psychology, University of Vermont, Burlington, VT 05405.

Erin Roland, Department of Psychology, University of Vermont, Burlington, VT 05405.

Jennifer Potts, Department of Psychology and Human Development, Peabody College, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 37203.

Kelly Haker, Department of Psychology and Human Development, Peabody College, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 37203.

Jennifer E. Champion, Department of Psychology and Human Development, Peabody College, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 37203

Bruce E. Compas, Department of Psychology and Human Development, Peabody College, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 37203

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles. Burlington, VT: Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Alderfer MA, Fiese BH, Gold JI, Holmbeck GN, Goldbeck L, Chambers CT, Abad M, Spetter D, Patterson J. Evidence-based assessment in pediatric psychology: Family measures. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2008;33:1046–1061. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA. Mindfulness-based treatment approaches : clinician’s guide to evidence base and applications. Amsterdam ; Boston: Elsevier Academic Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri W. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories -IA and -II in psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1996;67:588–597. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition manual. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop S, Lau M, Shapiro S, Carlson L, Anderson N, Carmody J, Velting D. Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology Science and Practice. 2004;11:230–241. [Google Scholar]

- Brown KW, Ryan RM. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well- being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:822–848. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke L. The impact of maternal depression on familial relationships. International Review of Psychiatry. 2003;15:243–255. doi: 10.1080/0954026031000136866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth JD, Duncan LG, Greenberg MT, Nix RL. Changing parent’s mindfulness, child management skills and relationship quality with their youth: Results from a randomized pilot intervention trial. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2010;19:203–217. doi: 10.1007/s10826-009-9304-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JAS, Semple RJ. Mindful parenting: A call for research. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2010;19:145–151. [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Forehand R, Keller G, Champion JE, Rakow A, Reeslund KL, Cole DA. Randomized controlled trial of a family cognitive-behavioral preventive intervention for children of depressed parents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:1007–1020. doi: 10.1037/a0016930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Champion JE, Forehand R, Cole DA, Reeslund KL, Fear J, Roberts L. Coping and Parenting: Mediators of 12-month outcomes of a family group cognitive-behavioral preventive intervention with families of depressed parents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;68:623–634. doi: 10.1037/a0020459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGarmo DS, Patterson GR, Forgatch MS. How do outcomes in a specified parent training intervention maintain or wane over time? Prevention Science. 2004;5:73–89. doi: 10.1023/b:prev.0000023078.30191.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dix T, Meunier LN. Depressive symptoms and parenting competence: An analysis of 13 regulatory processes. Developmental Review. 2009;29:45–68. [Google Scholar]

- Dumas JE. Mindfulness-based parent training: Strategies to lessen the grip of automaticity in families with disruptive children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:779–791. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3404_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan LG, Coatsworth JD, Greenberg MT. A model of mindful parenting: Implications for parent-child relationships and prevention research. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2009;12:255–270. doi: 10.1007/s10567-009-0046-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ensminger ME, Forthergill K. A decade of measuring SES: What it tells us and where to go from here in Bornstein. In: Marc, Bradley RH, editors. Socioeconomic status, parenting, and child development. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2003. pp. 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition (SCID-I/P) New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, Patterson GR, Degarmo DS, Beldavs ZG. Testing the Oregon delinquency model with 9-year follow-up of the Oregon Divorce Study. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:637–660. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner F, Hutchings J, Bywater T, Whitaker C. Who benefits and how does it work? Moderators and mediators of outcome in an effectiveness trial of a parenting intervention. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2010;39:568–580. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2010.486315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH. Depression in mothers. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2007;3:107–135. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Gotlib IH. Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: a developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychological Reveiw. 1999;106:458–490. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.106.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Sawyer AT, Witt AA, Oh D. The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical psychology. 2010;78:169–183. doi: 10.1037/a0018555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaser SS, Langrock AM, Keller G, Merchant MJ, Benson MA, Reeslund K, Compas BE. Coping with the stress of parental depression II: Adolescent and parent reports of coping and adjustment. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:193–205. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. Wherever you go, there you are. Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. New York: Hyperion; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Ryan N. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingston T, Dooley B, Bates A, Lawlor E, Malone K. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for residual depressive symptoms. Psychology and Psychotherapy. 2007;80:193–203. doi: 10.1348/147608306X116016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy MC, Graczyk PA, O’Hare E, Neuman G. Maternal depression and parenting behavior: a meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20:561–592. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Anderson EJ. Further psychometric validation of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2007;29:289–293. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon RJ, Wells KC, Kotler JS. Conduct Problems. In: Mash EJ, Barkley RA, editors. Treatment of childhood disorders. 3. New York: Guilford; 2006. pp. 137–268. [Google Scholar]

- Melby JN, Conger RD. The Iowa Family Interation Rating Scales: Instrument summary. In: Kerig PK, Lindahl KM, editors. Family observational coding system: Resources for systemtic research. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2001. pp. 33–58. [Google Scholar]

- Melby JN, Conger RD, Book R, Rueter M, Lucy L, Repinski D, et al. Unpublished manuscript. 5. Institute of Social and Behavioral Research, Iowa State University; Ames, Iowa: 1998. The Iowa Family Interation Rating Scales. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council & Institute of Medicine. Depression in parents, parenting, and children: Opportunities to improve identification, treatment, and prevention. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. The other end of the continuum: The cost of rumination. Psychological Inquiry. 1998;9:216–219. [Google Scholar]

- Rakow A, Forehand R, McKee L, Coffelt N, Champion J, Fear J, Compas BE. The relation of parental guilt induction to child internalizing problems when a caregiver has a history of depression. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2009;18:367–377. doi: 10.1007/s10826-008-9239-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakow A, Forehand R, McKee LG, Champion JE, Haker K, Roberts L, Compas BE. The association of parental depressive symptoms with child internalizing problems: The role of parental guilt induction. Journal of Family Psychology in press, contingent on final revisions. [Google Scholar]

- Roelofs J, Rood L, Meesters C, te Dorsthorst V, Bogels S, Alloy LB, Nolen-Hoeksema S. The influence of rumination and distraction on depressed and anxious mood: a prospective examination of the response styles theory in children and adolescents. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;18:635–642. doi: 10.1007/s00787-009-0026-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal ZV, Williams JMG, Teasdale JD. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: A new approach to preventing relapse. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Singh NN, Lancioni GE, Winton AS, Curtis WJ, Wahler RG, Sabaawi M, McAleavey K. Mindful staff increase learning and reduce aggression in adults with developmental disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2006;27:545–558. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh NN, Lancioni GE, Winton AS, Singh J, Curtis WJ, Wahler RG, McAleavey K. Mindful parenting decreases aggression and increases social behavior in children with developmental disabilities. Behavior Modification. 2007;31:749–771. doi: 10.1177/0145445507300924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh NN, Lancioni GE, Winton ASW, Singh J, Singh AN, Adkins AD, Wahler RG. Training in mindful caregiving transfers to parent-child interactions. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2010;19:167–174. [Google Scholar]

- Singh NN, Singh AN, Lancioni GE, Singh J, Winton ASW, Adkins AD. Mindfulness training for parents and their children with ADHD increases the children’s compliance. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2010;19:157–166. [Google Scholar]

- Skre I, Onstad S, Torgerse S, Kringlen E. Higher interrater reliability for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Axis I (SCID-I) Acta Psychiatria Scaminavica. 1991;84:167–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1991.tb03123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymtotic confidence intervals for indirect effects of structural equation models. In: Leinhardt S, editor. Sociological Methodology. Washington DC: American Sociological Association; 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale JD. Cognitive vulnerability to persistent depression. Cognition and Emotion. 1988;2:247–274. [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Skodol AE, Bender D, Dolan R, Sanislow C, Schaefer E, Gunderson JG. The collaborative longitudinal personality disorder study: Reliability of Axis I and II diagnosis. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2000;14:291–299. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2000.14.4.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]