Abstract

Purpose of the review

The developmental switch from fetal to adult hemoglobin has long fascinated biologists and attracted hematologists given its importance for patients with hemoglobin disorders. New discoveries have reinvigorated the field of globin gene regulation. These results hold promise for improved treatment of the major hemoglobinopathies.

Recent findings

Both genome-wide association studies and traditional linkage studies have identified several genetic loci involved in silencing fetal hemoglobin. BCL11A is a potent silencer of fetal hemoglobin in both mouse and man. It controls the beta-globin gene cluster in concert with other factors. KLF1, a vital erythroid transcription factor, activates BCL11A and assists in coordinating the switch from fetal to adult hemoglobin. A regulatory network of cell-intrinsic and cell-extrinsic factors maintains the epigenetic homeostasis of the beta-globin cluster and accounts for the precise lineage-specific and developmental stage-specific regulation of the globin genes.

Summary

With an improved understanding of pathways involved in the switch from fetal to adult hemoglobin, new targets have emerged for the treatment of the common hemoglobin disorders, sickle cell anemia and beta-thalassemia.

Keywords: fetal hemoglobin, gamma-globin, BCL11A, KLF1, epigenetics

Introduction

A maxim of pediatrics is that developmental stage influences disease expression. In few cases is this more evident than the hemoglobin disorders. Each hemoglobin tetramer is composed of two alpha-like and two beta-like globin polypeptides. Whereas deficient alpha-globin expression causes critical prenatal anemia and fetal hydrops, deficient beta-globin expression is associated with relatively mild or even silent clinical outcomes at birth with disease manifestations delayed until infancy. This disparity is because beta-globin is not a constituent of fetal hemoglobin (HbF), a tetramer of two alpha- and two gamma-globin chains. Around birth, expression of gamma-globin is progressively silenced and beta-globin expression is activated. Individuals with beta-globin disorders have clinical courses whose severity is inversely proportional to the degree of preservation of HbF expression. Rare individuals with beta-hemoglobinopathies and hereditary persistence of fetal hemoglobin (HPFH) do not manifest disease [1]. (Even though fetal hemoglobin has a slightly higher affinity for oxygen than does adult hemoglobin, individuals with HPFH are completely healthy.) The structurally normal gamma-globin is able to substitute for the absent beta-globin in beta-thalassemia and disrupt sickle hemoglobin-associated polymerization in sickle cell disease. The most successful HbF inducer in the pharmacologic armamentarium is hydroxyurea [2-4]. Hydroxyurea reduces the frequency and severity of sickle cell crises and may forestall end-organ damage [5-7]. However, hydroxyurea has inconsistent effectiveness, requires careful monitoring, and has limited utility for the treatment of beta-thalassemia. There remains an unmet need for more efficient, safe, and tolerable means of HbF induction. In this context, recent advances in the understanding of the developmental regulation of globin gene expression (“hemoglobin switching”) hold promise for the development of novel therapeutic strategies for beta-hemoglobinopathies.

Hemoglobin switching

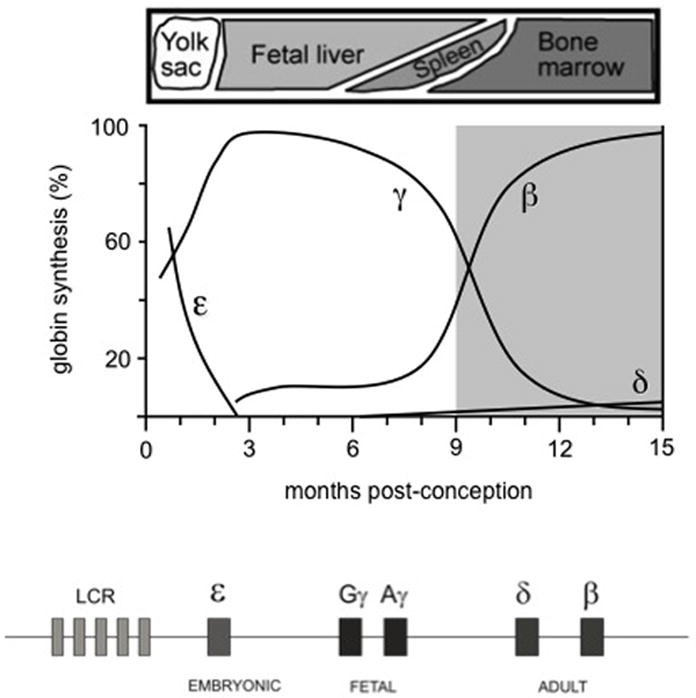

Five beta-like globin genes reside in a single gene cluster (see Figure 1). HBE encodes epsilon-globin, expressed during early embryogenesis in primitive erythrocytes derived from the yolk sac; HBG1 and HBG2 encode gamma-globin, expressed from mid-gestation until infancy; and HBD and HBB encode delta- and beta-globin which compose the minor and major forms of adult hemoglobin, predominating after birth. The acquisition of fetal-stage gamma-globin occurred during primate evolution so in most animals (including the lab mouse) there are only embryonic and adult globin genes. Two hemoglobin switches occur through human ontogeny, initially from embryonic to fetal globins and later from fetal to adult. The clinically relevant aspect of the switch with regard to beta-hemoglobinopathies is the repression of gamma-globin in adult-stage erythroblasts.

Figure 1. Developmental regulation of the beta-globin locus.

Top, relative expression of beta-like globin genes through ontogeny. Bottom, schematic of the beta-globin locus, including five genes and a distal regulatory element known as the locus control region (LCR), Graph modified from [8].

Maturational switching describes the finding that initial stages of erythroid differentiation are relatively permissive for gamma-globin expression whereas terminal stages restrict expression to beta-globin [9]. HbF production is enhanced following acute erythropoietic stress, such as after hemorrhage, hemolysis, or recovery from chemotherapy. This HbF surge may be due to the accelerated expansion of early erythroid progenitors that retain gamma-globin expression potential. Cytotoxic agents [10] such as hydroxyurea were first explored for use in HbF induction because of the hypothesis that they might alter the kinetics of erythropoiesis in a manner similar to “stress erythropoiesis.”

HPFH is caused by two classes of mutations, one involving large deletions at the beta-globin cluster and the other involving point mutations in the promoters of the gamma-globin genes. Deletional HPFH is associated with both the loss of repressive intergenic sequences and the juxtaposition of distant enhancers [1,11,12]. Nondeletional forms of HPFH suggest that the promoters of the gamma-globin genes interact with repressive factors.

Conceptual formulations of hemoglobin switching have distinguished between autonomous and competitive modes of control. In autonomous models, gamma-globin is repressed in the adult stage due solely to the trans-acting environment whereas in competitive models, gamma-globin repression depends on the presence of an adjacent beta-globin gene within the cluster. Several lines of evidence support competition of endogenous human globin genes: residual HbF in the adult-stage is not evenly distributed among erythrocytes but rather has a limited expression in a few red blood cells called F-cells; patients with beta-thalassemia typically demonstrate reciprocal elevations of HbF; and heterozygotes with HPFH have decreased expression of beta-globin from the affected but not the unaffected allele [13]. Each beta-globin cluster contains a distal regulatory element (known as the locus control region, or LCR) required for appropriate globin gene expression [14,15]. The LCR participates in long-range looping interactions with individual globin genes, with only one productive LCR-globin gene interaction possible at a given time [16]. However, transgenic mice with an LCR linked solely to gamma-globin in the absence of adjacent globin genes demonstrate partial silencing during development, demonstrating that at least some of the switch is autonomous [17,18]. Even in competitive models (in which cis-acting interactions are emphasized), some stage-specific trans-acting mechanisms must be invoked to initiate and maintain the switch.

A silencer of gamma-globin

Although intense efforts have focused on the biochemical characterization of globin gene regulation [19-25], major breakthroughs in the field of hemoglobin switching continue to come from human genetics. Perhaps genotype-phenotype correlations are particularly instructive because the problem is limited to control of a single gene within a single lineage.

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) take advantage of common polymorphisms to relate phenotypes to variation at discrete loci. GWAS, applied to the problem of HbF variation, have yielded consistent and striking findings, across ethnicities and among healthy individuals and those with beta-hemoglobinopathies: a meaningful fraction of the variation in HbF levels is accounted for by common polymorphisms at just three loci [26-32]. These loci include the beta-globin cluster itself (not surprising since rare mutations here result in HPFH), an intergenic interval between the HBS1L and MYB genes (previously identified by linkage analysis of a family with elevated HbF [33]), and BCL11A. BCL11A, not previously implicated in hemoglobin switching, was an intriguing candidate, as it is a zinc-finger transcriptional repressor active in other hematopoietic lineages (B lymphoid cells) and expressed in erythroid cells.

Studies from our lab and others have shown that BCL11A silences gamma-globin. Knockdown of BCL11A enhances HbF production in human erythroid progenitors [34]. Knockout of BCL11A in the mouse profoundly delays the single switch from embryonic-to-adult globins as well as silencing of gamma-globin carried on a human beta-globin cluster transgene [35]. BCL11A does not occupy the gamma-globin promoter but binds to the LCR as well as intergenic regions in the cluster [34,36,37] previously associated with gamma-globin repression [1,11].

BCL11A associates with various partners within erythroid multiprotein complexes [34,36,37], including the repressive nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase complex (NuRD), GATA1, the erythroid master regulator, and SOX6, a transcription factor previously shown to repress embryonic-globins in mice [38-41]. Unlike BCL11A, SOX6 directly occupies the gamma-globin promoter and double knockdown of BCL11A and SOX6 has an additive effect on HbF derepression, suggesting that BCL11A may exert part of its gamma-globin repression with SOX6 [36].

Trans-acting factors important in globin gene regulation must themselves be developmentally regulated to be effectors of the physiologic switch. In the adult stage, BCL11A is expressed at high levels whereas in embryonic and fetal stages, its expression level is much lower and shorter isoforms predominate [34,35]. Future studies will help determine the extent to which erythroid BCL11A is subject to post-translational control such as proteolytic cleavage or SUMOylation [34,42,43]. BCL11A is also under transcriptional control [36], with its locus occupied by GATA1 [37]. Therefore BCL11A appears to be a new therapeutic target for HbF induction. One issue will be the degree to which inhibition of BCL11A has non-erythroid effects, such as in B cells.

A master erythroid regulator

The next clue in the hemoglobin switching puzzle again came from human genetics. The first hint was a patient with congenital dyserythropoeitic anemia (CDA) found to have persistently elevated HbF and a mutation in the KLF1 gene causing a single amino acid substitution in the second zinc finger of this transcription factor [44]. Recently, a mouse mutation called Nan (for neonatal anemia) was mapped to a substitution of the equivalent zinc finger residue within KLF1 [39,45]. Heterozygous Nan mice have chronic hemolytic anemia and persistently elevated embryonic globin expression [39]. The Nan allele is associated with more severe phenotypes than the simple KLF1 knockout indicating neomorphic properties. Of note, individuals with loss-of-function KLF1 mutations were known to display the In(Lu) phenotype (disturbed expression of certain blood group antigens) but were not reported to have deranged globin gene expression [46]. Subsequently, a novel form of HPFH in a Maltese kindred was mapped to heterozygous nonsense mutations in the first zinc finger of KLF1 [47]. Unlike the neomorphic Nan mutation, Maltese HPFH appears to be due to a haploinsufficient KLF1 allele. Further characterization will be required to compare this allele to those associated with the In(Lu) phenotype.

Knockdown of KLF1 in human erythroid progenitors derepresses HbF [47,48]. KLF1 (also known as EKLF) was first characterized as an erythroid transcription factor binding to CACCC motifs [49]. Thalassemia intermedia patients with mutations in the CACCC box of the beta-globin promoter were described nearly thirty years ago [50], and these patients demonstrate significant elevation of HbF [51]. KLF1 is a potent activator of beta-globin in vivo, as demonstrated by knockout mice that succumb to fatal beta-thalassemia [52-54]. Careful observation of these mice (and those bearing a human beta-globin cluster transgene) prior to their death demonstrates delayed silencing of mouse embryonic globin and human transgenic gamma-globin genes in the homozygous and heterozygous KLF1 mutants [55,56].

Surprisingly, gene expression profiling of erythroid progenitors in patients with Maltese HPFH demonstrated decreased expression of BCL11A [47]. Knockdown of KLF1 led to decreased BCL11A in normal erythroid progenitors and reexpression of KLF1 rescued BCL11A expression in erythroid progenitors of patients with Maltese HPFH [47]. In a parallel study, mice with a hypomorphic KLF1 allele demonstrated delayed silencing of murine embryonic globins (and transgenic human gamma-globin) and reduced BCL11A [48]. KLF1 occupies the BCL11A promoter [47,48].

These studies suggest a model in which KLF1 has dual functions. First, it influences gamma-globin silencing by providing the beta-globin gene a competitive advantage, and second, it activates the gamma-globin silencer BCL11A. This seeming reconciliation of competitive and autonomous models begs the question of how KLF1 itself is developmentally regulated. Although KLF1 modestly increases in concentration between embryonic and adult stages [57,58], it is active and competent for high-level beta-globin expression in the embryonic stage [54,59] suggesting that layers of its regulation remain obscure. Furthermore in mice carrying a human beta-globin cluster transgene, the magnitude of gamma-globin derepression observed in KLF1 deficiency is much less than that seen in BCL11A deficiency implying additional relevant inputs to BCL11A regulation. KLF1 not only coordinates globin gene expression but also is a regulator involved in supporting many aspects of erythroid biology [60-62]. Various KLF factors play redundant and opposing roles in vivo [59,63]. Therefore interventions aimed at inducing HbF by inhibiting KLF1 might have a narrow therapeutic window.

The other locus highlighted by GWAS is the intergenic interval between HBS1L and MYB. While studies have conflicted as to which of these two genes regulates HbF [64-66], the weight of evidence points to c-Myb, an erythroid transcription factor [67]. A recent study demonstrated that knockdown of c-Myb during erythroid differentiation of human hematopoietic progenitors was associated with decreased expression of KLF1 [68]. The simple model implied by this study that c-Myb represses gamma-globin via KLF1 activation of BCL11A awaits experimental support.

The importance of epigenetics

Chromatin modifying activities participate in the hemoglobin switch. The gamma-globin gene becomes methylated in the adult stage while the beta-globin gene remains unmethylated [69,70]. The gamma-globin promoter is occupied by multiprotein repressive complexes including the arginine methyltransferase PRMT5, the DNA methylating enzyme DNMT3A, the lysine methyltransferase SUV4-20h1, the serine/threonine kinase CK2alpha, and components of NuRD [71,72]. Teasing out the role of the sundry chromatin modifying activities residing at the beta-globin cluster remains a challenge. Recent approaches have begun to scrutinize these complexes with surprising results. NuRD appeared to be an excellent candidate for mediating repression of gamma-globin, in concert with BCL11A [34] and GATA1-FOG1 [25], among other partners. A FOG1 mutation engineered to lack the NuRD binding domain and knocked-in to the endogenous locus does not impair transgenic human gamma-globin (or endogenous murine embryonic globin) silencing but paradoxically leads to decreased beta-globin expression [73]. This suggests a perplexing model in which the GATA1-FOG1-NuRD complex is required for globin activation (rather than repression). Whether NuRD plays this unforeseen role within other complexes remains to be seen.

Another insight has come from study of PRMT1, an arginine methyltransferase linked to activation of beta-globin [74]. Surprisingly, knockdown of FOP (Friend of PRMT1), a recently identified PRMT1 partner, causes significant derepression of gamma-globin [75]. FOP expression rises from fetal to adult stages, suggesting it might participate in the physiologic switch. Numerous questions remain regarding the function of this factor, including whether these effects are through PRMT1, other methyltransferases, or via an altogether different pathway.

The physiologic switch depends on the interplay between the erythroblast-intrinsic machinery and signals emanating from the stage-specific niche. A population of fetal hepatic stromal cells has recently been identified that support hematopoietic cells by expressing cytokines such as SCF, which are differentially regulated in fetal liver compared to bone marrow [76].SCF promotes maintenance of HbF expression [77,78] and this cytokine alters the distribution of histone marks within the beta-globin cluster [79]. The SCF receptor decreases on erythroid progenitors from fetal to adult life, targeted by the adult stage-specific microRNAs miR-221 and miR-222 [80].

Beginnings of a network

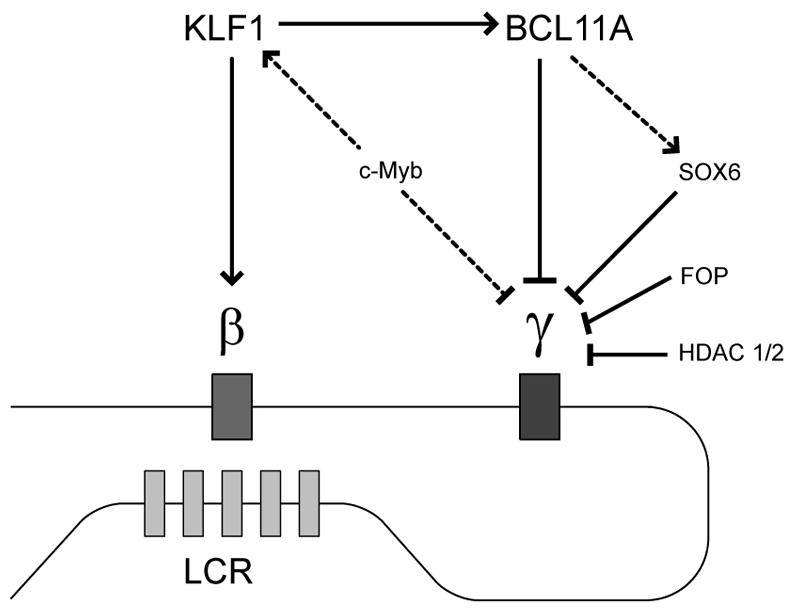

A host of new players implicated in repressing HbF present as therapeutic targets for the treatment of beta-hemoglobinopathies (see Figure 2). A critical task will be to place these factors into a unified hierarchy, comparing various regulators in terms of quantitative effects on globin expression, relationships to other factors, non-globin effects on erythropoiesis, and impacts outside of the erythroid lineage. A granular network of HbF regulatory pathways will help prioritize the most promising leads for further clinical development.

Figure 2. An emerging network of fetal hemoglobin regulation.

In the adult stage, the beta-globin gene, engaged in long-range looping interactions with the LCR, is expressed while the gamma-globin gene is repressed. Regulators of this process comprise therapeutic targets for beta-hemoglobinopathies. Positive and negative interactions are denoted by pointed and blunt arrows, respectively. Dotted lines indicate relationships with a lower level of experimental support.

Key regulators of the globin switch may serve as direct targets for small molecules. DNA-binding transcription factors such as BCL11A or KLF1 have been considered challenging targets for drug development although recent advances may extend the reach of small molecules [81]. Since these transcription factors cooperate with chromatin modifying activities, traditional enzyme inhibitors may also have a role in HbF induction. The imperative will be to define activities that have limited effects outside of hemoglobin switching. Demethylating agents have been explored; promising results with 5-azacytidine in a beta-thalassemia patient were noted nearly 30 years ago [82]. Decitabine, a demethylator with a more encouraging safety profile, has shown impressive HbF induction in primate models [43] and remains in clinical development. Histone deacetylase inhibitors also have potential to induce HbF [83-85]. A recent study integrated high-throughput cell-based screening, an extensive library of HDAC inhibitors, and RNA interference, to define HDAC1 and HDAC2 as the specific deacetylases responsible for HbF repression [86]. Selective HDAC modulators might achieve HbF induction while avoiding toxicity. Advanced chemical biology methods may allow for agnostic screens to probe undiscovered pathways influencing the globin switch.

Genetic and cellular therapeutics may also have a role. Such strategies could include the in vivo application of RNA interference [87], engineered transcription factors [88], or the use of stem cells [89]. Recently an artificial transcription factor targeting the gamma-globin promoter was shown to derepress HbF [90]. This form of gene correction in trans is one of many potential strategies to reverse the switch.

Conclusion

The study of hemoglobin switching was reinvigorated by the recent discovery of BCL11A as a potent silencer of gamma-globin. The finding that KLF1 promotes fetal hemoglobin repression through activation of both beta-globin and BCL11A assimilates competitive and autonomous models. A tentative network of fetal hemoglobin regulation materializes, involving c-Myb, KLF1, and BCL11A, and integrating epigenetic mechanisms with extrinsic influences. Despite great progress in the field, only half the variance in fetal hemoglobin levels has been explained, suggesting uncharted insights will help clarify the system and prioritize clinical development.

Acknowledgments

Work from the authors’ laboratory was supported in part by grants from the NIH. SHO is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. The authors thank members of the laboratory for helpful discussions and J. Desimini for graphical assistance.

Funding disclosure: Work from the authors’ laboratory was supported in part by grants from the NIH. SHO is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

One and two bulleted annotations

*Aerbajinai, W., Zhu, J., Kumkhaek, C., Chin, K. and Rodgers, G. P. SCF induces gamma-globin gene expression by regulating downstream transcription factor COUP-TFII 2009

The authors demonstrate that SCF suppresses COUP-TFII, a known repressor of gamma-globin, via the ERK pathway. This study uniquely addresses the study of cell-extrinsic and cell-intrinsic mechanisms of gamma-globin regulation.

**Bianchi, E., Zini, R., Salati, S., et al. c-Myb supports erythropoiesis through the transactivation of KLF1 and LMO2 expression 2010

Using a knockdown approach in human hematopoietic progenitors, the authors show that c-Myb promotes erythropoiesis through activation of KLF1 and LMO2(a component of the GATA1-TAL1 complex). This result is intriguing given the association of polymorphisms at the HBS1L-MYB intergenic interval with HbF level. The model implied by this study that c-Myb represses gamma-globin via KLF1 activation of BCL11A awaits experimental support.

**Borg, J., Papadopoulos, P., Georgitsi, M., et al. Haploinsufficiency for the erythroid transcription factor KLF1 causes hereditary persistence of fetal hemoglobin 2010

This important study maps a novel form of HPFH to mutations in KLF1. Surprisingly, BCL11A is deficient in these patients due to insufficient activation by KLF1. KLF1 appears to effect hemoglobin switching through both competitive and autonomous modes. It remains unclear how various KLF1 mutations result in such disparate erythroid phenotypes.

*Bottardi, S., Ross, J., Bourgoin, V., et al. Ikaros and GATA-1 combinatorial effect is required for silencing of human gamma-globin genes 2009

The authors demonstrate that Ikaros, previously reported as a repressor of gamma-globin, is required for GATA1 occupancy of the gamma-globin promoter and the appropriate distribution of chromatin activities and repressive marks.

**Bradner, J. E., Mak, R., Tanguturi, S. K., et al. Chemical genetic strategy identifies histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) and HDAC2 as therapeutic targets in sickle cell disease 2010

This report uses chemical screening and RNA interference to demonstrate the role of HDAC1 and HDAC2 in gamma-globin repression. The results suggest that selective HDAC inhibitors might derepress HbF while limiting systemic toxicity. Moreover, the study highlights the utility of high-throughput chemical genetics.

*Chin, J., Singh, M., Banzon, V., et al. Transcriptional activation of the gamma-globin gene in baboons treated with decitabine and in cultured erythroid progenitor cells involves different mechanisms 2009

The authors extend their previous studies on decitabine in baboons, showing that drug treatment causes demethylation of the gamma-globin promoter as well as the acquisition of active histone marks. Since it possesses endogenous gamma-globin (unlike the mouse), the baboon is a key animal model for exploring new therapeutics.

**Chou, S., Lodish, H. F. Fetal liver hepatic progenitors are supportive stromal cells for hematopoietic stem cells 2010

The authors isolated rare fetal liver cells that could support the expansion of fetal hematopoietic stem cells. These stromal cells were shown to be alpha-fetoprotein-expressing hepatic stem or progenitor cells. The stromal cells expressed cytokines differentially regulated between fetal liver and adult bone marrow. This study highlights fundamental distinctions between fetal and adult hematopoiesis.

**Gabbianelli, M., Testa, U., Morsilli, O., et al. Mechanism of human Hb switching: a possible role of the kit receptor/miR 221-222 complex 2010

The authors show that kit (the SCF receptor) is progressively silenced during development, suggesting that SCF may participate in the physiological hemoglobin switch. Moreover, they demonstrate that the erythroid microRNAs miR-221 and miR-222 target kit and are more highly expressed in the adult compared to fetal stage. MicroRNAs surface as a therapeutic target for HbF induction.

*Gazouli, M., Katsantoni, E., Kosteas, T. and Anagnou, N. P. Persistent fetal gamma-globin expression in adult transgenic mice following deletion of two silencer elements located 3′ to the human Agamma-globin gene 2009

Using detailed transgenic studies, the authors describe a cis element repressing gamma-globin expression in the adult stage. Future studies using similar transgenes will help define the interactions that establish hemoglobin switching in vivo; for example, it is possible that BCL11A exerts its gamma-globin repressive effect via interactions with such cis elements.

*Heruth, D. P., Hawkins, T., Logsdon, D. P., et al. Mutation in erythroid specific transcription factor KLF1 causes Hereditary Spherocytosis in the Nan hemolytic anemia mouse model 2010

This study, like that of Siatecka et al, maps the Nan mutation to KLF1. The authors propose a model in which this mutant encodes an abnormal KLF1 protein with altered DNA-binding properties.

**Jawaid, K., Wahlberg, K., Thein, S. L. and Best, S. Binding patterns of BCL11A in the globin and GATA1 loci and characterization of the BCL11A fetal hemoglobin locus 2010

This important report using high-resolution ChIP-chip in human adult erythroid progenitors confirms that BCL11A, although occupying the beta-globin cluster, occupies neither the gamma-globin nor the beta-globin promoter. Rather BCL11A occupies important regulatory regions including the LCR and several loci in the gamma-delta intergenic interval. Furthermore, BCL11A and GATA-1 often appear to share co-occupancy, indicating they may participate in a multi-subunit complex. GATA1 binds to intronic regions of the BCL11A gene, adjacent to HbF-associated SNPs, suggesting that these polymorphisms mark key regulatory elements.

*Lebensburger, J. D., Pestina, T. I., Ware, R. E., Boyd, K. L. and Persons, D.A. Hydroxyurea therapy requires HbF induction for clinical benefit in a sickle cell mouse model 2010

This report supports the concept that hydroxyurea ameliorates sickle cell disease via HbF induction. The authors demonstrate no salutary effects of hydroxyurea on anemia or end-organ compromise in a murine model of sickle cell disease (which lacks gamma-globin) whereas ectopic gamma-globin expression was able to reverse the disease phenotype.

*Miccio, A., Blobel, G. A. Role of the GATA-1/FOG-1/NuRD pathwayin the expression of human beta-like globin genes 2010

With knock-in mice bearing a FOG1 mutation that ablates the NuRD binding domain, the authors surprisingly show that the GATA1-FOG1-NuRD complex promotes globin activation (rather than repression). This study shows the challenges in deconvoluting multiprotein complexes.

*Rank, G., Cerruti, L., Simpson, R. J., Moritz, R. L., Jane, S. M. and Zhao, Q. Identification of a PRMT5-dependent repressor complex linked to silencing of human fetal globin gene expression 2010

The authors show that the lysine methyltransferase SUV4-20h1 is a member of the PRMT5 complex at the gamma-globin promoter and that knockdown of SUV4-20h1 results in derepression of gamma-globin. This study reveals that chromatin-modifying activities (i.e. “druggable targets”) actively participate in hemoglobin switching.

**Sankaran, V. G., Xu, J., Ragoczy, T., et al. Developmental and species-divergent globin switching are driven by BCL11A 2009

This report demonstrates that BCL11A participates in physiologic hemoglobin switching. Profound derepression of transgenic human gamma-globin and endogenous embryonic globins accompanies BCL11A deficiency in mice. Significant delay in hemoglobin switching occurs in heterozygous animals showing that BCL11A is a quantitative silencer of gamma-globin. BCL11A expression is developmentally regulated although the mechanisms of this remain incompletely characterized.

**Siatecka, M., Sahr, K. E., Andersen, S. G., Mezei, M., Bieker, J. J. and Peters, L. L. Severe anemia in the Nan mutant mouse caused by sequence-selective disruption of erythroid Kruppel-like factor 2010

The ENU-induced Nan (neonatal anemia) allele is mapped to a missense mutation of KLF1 affecting an equivalent residue in the second zinc finger as a human KLF1 mutation causing congenital dyserythropoietic anemia and elevated HbF. Unlike the KLF1+/- mouse, the Nan heterozygote is anemic with persistent embryonic globin expression, and the Nan homozygote is embryonic lethal at an earlier stage than is the KLF1 null mouse, suggesting that the Nan allele has neomorphic or dominant negative properties, apparently due to altered DNA-binding specificity. This study confirms the role of KLF1 in hemoglobin switching and highlights that various KLF1 alleles have disparate erythroid phenotypes.

*Spyrou, P., Phylactides, M., Lederer, C. W., et al. Compounds of the anthracycline family of antibiotics elevate human gamma-globin expression both in erythroid cultures and in a transgenic mouse model 2010

This study demonstrates that anthracyclines currently used clinically for the treatment of malignancies can at low-doses induce HbF. It remains to be determined if the HbF-inducing activity of these agents can be dissociated from their cytotoxicity.

*Sripichai, O.,Kiefer, C. M., Bhanu, N. V., et al. Cytokine-mediated increases in fetal hemoglobin are associated with globin gene histone modification and transcription factor reprogramming 2009

The authors extend their previous findings that the cytokines SCF and TGF-beta derepress gamma-globin in ex vivo cultured human erythroblasts and demonstrate that these cytokines cause changes in chromatin occupancy at the beta-globin cluster. This study provides an example of how cell-extrinsic influences may bear on epigenetic regulation.

*van Dijk, T. B., Gillemans, N., Pourfarzad, F., et al. Fetal globin expression is regulated by Friend of Prmt1 2010

In this brief report, the authors show that FOP (Friend of PRMT1) is a repressor of gamma-globin in adult erythroid cells. It is unclear if FOP mediates this effect through its namesake PRMT1, other arginine methyltransferases such as PRMT5, or through a methyltransferase-independent pathway.

*Wilber, A., Tschulena, U., Hargrove, P. W., et al. A zinc-finger transcriptional activator designed to interact with the gamma-globin gene promoters enhances fetal hemoglobin production in primary human adult erythroblasts 2010

The authors designed an artificial transcription factor composed of a transcriptional activation domain and a gamma-globin promoter DNA binding domain. This construct led to significant activation of HbF in human hematopoietic progenitors. This creative application of gene correction in trans demonstrates a novel strategy for genetic therapeutics.

**Xu, J., Sankaran, V. G., Ni, M., et al. Transcriptional silencing of {gamma}-globin by BCL11A involves long-range interactions and cooperation with SOX6 2010

This report, along with that of Jawaid et al, uses high-resolution ChIP-chip to show that BCL11A binds to the beta-globin cluster not at the gamma-globin or beta-globin genes themselves but at distant sites, including the LCR and gamma-delta intergenic intervals. BCL11A is shown to promote long-range interactions between the LCR and HBB at the expense of HBG. BCL11A also interacts with SOX6, a known repressor of murine embryonic globins. SOX6 is shown to repress gamma-globin in adult human erythroid progenitors and to occupy the gamma-globin promoter. Therefore, BCL11A may act with various partners to effect repression of gamma-globin. Future experiments will help characterize the critical multiprotein complexes and beta-globin regulatory sequences through which BCL11A represses gamma-globin.

**Zhou, D., Liu, K., Sun, C. W., Pawlik, K. M. and Townes, T. M. KLF1 regulates BCL11A expression and gamma- to beta-globin gene switching 2010

This study characterizes mice with hypomorphic alleles of KLF1 with delayed hemoglobin switching. Similar to the Maltese HPFH kindred, these mice have decreased levels of BCL11A and KLF1 binds to the BCL11A promoter. An important avenue for future study is defining the developmental transition that promotes KLF1-dependent BCL11A activation.

References

- 1.Bank A. Regulation of human fetal hemoglobin: new players, new complexities. Blood. 2006 Jan 15;107(2):435–443. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Platt OS. Hydroxyurea for the treatment of sickle cell anemia. N Engl J Med. 2008 Mar 27;358(13):1362–1369. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct0708272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ware RE. How I use hydroxyurea to treat young patients with sickle cell anemia. Blood. 2010 Jul 1;115(26):5300–5311. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-146852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lebensburger JD, Pestina TI, Ware RE, Boyd KL, Persons DA. Hydroxyurea therapy requires HbF induction for clinical benefit in a sickle cell mouse model. Haematologica. 2010 Apr 7; doi: 10.3324/haematol.2010.023325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charache S, Terrin ML, Moore RD, Dover GJ, Barton FB, Eckert SV, et al. Effect of hydroxyurea on the frequency of painful crises in sickle cell anemia. Investigators of the Multicenter Study of Hydroxyurea in Sickle Cell Anemia. N Engl J Med. 1995 May 18;332(20):1317–1322. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505183322001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steinberg MH, Barton F, Castro O, Pegelow CH, Ballas SK, Kutlar A, et al. Effect of hydroxyurea on mortality and morbidity in adult sickle cell anemia: risks and benefits up to 9 years of treatment. JAMA. 2003 Apr 2;289(13):1645–1651. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.13.1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang WC, Helms RW, Lynn HS, Redding-Lallinger R, Gee BE, Ohene-Frempong K, et al. Effect of hydroxyurea on growth in children with sickle cell anemia: results of the HUG-KIDS Study. J Pediatr. 2002 Feb;140(2):225–229. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.121383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noordermeer D, de Laat W. Joining the loops: beta-globin gene regulation. IUBMB Life. 2008 Dec;60(12):824–833. doi: 10.1002/iub.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stamatoyannopoulos G. Control of globin gene expression during development and erythroid differentiation. Exp Hematol. 2005 Mar;33(3):259–271. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spyrou P, Phylactides M, Lederer CW, Kithreotis L, Kirri A, Christou S, et al. Compounds of the anthracycline family of antibiotics elevate human gamma-globin expression both in erythroid cultures and in a transgenic mouse model. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2010 Mar-Apr;44(2):100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chakalova L, Osborne CS, Dai YF, Goyenechea B, Metaxotou-Mavromati A, Kattamis A, et al. The Corfu deltabeta thalassemia deletion disrupts gamma-globin gene silencing and reveals post-transcriptional regulation of HbF expression. Blood. 2005 Mar 1;105(5):2154–2160. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-4069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gazouli M, Katsantoni E, Kosteas T, Anagnou NP. Persistent fetal gamma-globin expression in adult transgenic mice following deletion of two silencer elements located 3’ to the human Agamma-globin gene. Mol Med. 2009 Nov-Dec;15(11-12):415–424. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2009.00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manca L, Masala B. Disorders of the synthesis of human fetal hemoglobin. IUBMB Life. 2008 Feb;60(2):94–111. doi: 10.1002/iub.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grosveld F, van Assendelft GB, Greaves DR, Kollias G. Position-independent, high-level expression of the human beta-globin gene in transgenic mice. Cell. 1987 Dec 24;51(6):975–985. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90584-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forrester WC, Takegawa S, Papayannopoulou T, Stamatoyannopoulos G, Groudine M. Evidence for a locus activation region: the formation of developmentally stable hypersensitive sites in globin-expressing hybrids. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987 Dec 23;15(24):10159–10177. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.24.10159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tolhuis B, Palstra RJ, Splinter E, Grosveld F, de Laat W. Looping and interaction between hypersensitive sites in the active beta-globin locus. Mol Cell. 2002 Dec;10(6):1453–1465. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00781-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Behringer RR, Ryan TM, Palmiter RD, Brinster RL, Townes TM. Human gamma- to beta-globin gene switching in transgenic mice. Genes Dev. 1990 Mar;4(3):380–389. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.3.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Enver T, Raich N, Ebens AJ, Papayannopoulou T, Costantini F, Stamatoyannopoulos G. Developmental regulation of human fetal-to-adult globin gene switching in transgenic mice. Nature. 1990 Mar 22;344(6264):309–313. doi: 10.1038/344309a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bottardi S, Ross J, Bourgoin V, Fotouhi-Ardakani N, Affar el B, Trudel M, et al. Ikaros and GATA-1 combinatorial effect is required for silencing of human gamma-globin genes. Mol Cell Biol. 2009 Mar;29(6):1526–1537. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01523-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aerbajinai W, Zhu J, Kumkhaek C, Chin K, Rodgers GP. SCF induces gamma-globin gene expression by regulating downstream transcription factor COUP-TFII. Blood. 2009 Jul 2;114(1):187–194. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-170712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanabe O, McPhee D, Kobayashi S, Shen Y, Brandt W, Jiang X, et al. Embryonic and fetal beta-globin gene repression by the orphan nuclear receptors, TR2 and TR4. EMBO J. 2007 May 2;26(9):2295–2306. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou W, Zhao Q, Sutton R, Cumming H, Wang X, Cerruti L, et al. The role of p22 NF-E4 in human globin gene switching. J Biol Chem. 2004 Jun 18;279(25):26227–26232. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402191200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Neill DW, Schoetz SS, Lopez RA, Castle M, Rabinowitz L, Shor E, et al. An ikaros-containing chromatin-remodeling complex in adult-type erythroid cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2000 Oct;20(20):7572–7582. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.20.7572-7582.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rupon JW, Wang SZ, Gaensler K, Lloyd J, Ginder GD. Methyl binding domain protein 2 mediates gamma-globin gene silencing in adult human betaYAC transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006 Apr 25;103(17):6617–6622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509322103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harju-Baker S, Costa FC, Fedosyuk H, Neades R, Peterson KR. Silencing of Agamma-globin gene expression during adult definitive erythropoiesis mediated by GATA-1-FOG-1-Mi2 complex binding at the -566 GATA site. Mol Cell Biol. 2008 May;28(10):3101–3113. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01858-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Menzel S, Garner C, Gut I, Matsuda F, Yamaguchi M, Heath S, et al. A QTL influencing F cell production maps to a gene encoding a zinc-finger protein on chromosome 2p15. Nat Genet. 2007 Oct;39(10):1197–1199. doi: 10.1038/ng2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uda M, Galanello R, Sanna S, Lettre G, Sankaran VG, Chen W, et al. Genome-wide association study shows BCL11A associated with persistent fetal hemoglobin and amelioration of the phenotype of beta-thalassemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Feb 5;105(5):1620–1625. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711566105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lettre G, Sankaran VG, Bezerra MA, Araujo AS, Uda M, Sanna S, et al. DNA polymorphisms at the BCL11A, HBS1L-MYB, and beta-globin loci associate with fetal hemoglobin levels and pain crises in sickle cell disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Aug 19;105(33):11869–11874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804799105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sedgewick AE, Timofeev N, Sebastiani P, So JC, Ma ES, Chan LC, et al. BCL11A is a major HbF quantitative trait locus in three different populations with beta-hemoglobinopathies. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2008 Nov-Dec;41(3):255–258. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galanello R, Sanna S, Perseu L, Sollaino MC, Satta S, Lai ME, et al. Amelioration of Sardinian beta0 thalassemia by genetic modifiers. Blood. 2009 Oct 29;114(18):3935–3937. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-217901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Solovieff N, Milton JN, Hartley SW, Sherva R, Sebastiani P, Dworkis DA, et al. Fetal hemoglobin in sickle cell anemia: genome-wide association studies suggest a regulatory region in the 5’ olfactory receptor gene cluster. Blood. 2010 Mar 4;115(9):1815–1822. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-239517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nuinoon M, Makarasara W, Mushiroda T, Setianingsih I, Wahidiyat PA, Sripichai O, et al. A genome-wide association identified the common genetic variants influence disease severity in beta0-thalassemia/hemoglobin. E Hum Genet. 2010 Mar;127(3):303–314. doi: 10.1007/s00439-009-0770-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Close J, Game L, Clark B, Bergounioux J, Gerovassili A, Thein SL. Genome annotation of a 1.5 Mb region of human chromosome 6q23 encompassing a quantitative trait locus for fetal hemoglobin expression in adults. BMC Genomics. 2004 May 31;5(1):33. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-5-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sankaran VG, Menne TF, Xu J, Akie TE, Lettre G, Van Handel B, et al. Human fetal hemoglobin expression is regulated by the developmental stage-specific repressor BCL11A. Science. 2008 Dec 19;322(5909):1839–1842. doi: 10.1126/science.1165409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sankaran VG, Xu J, Ragoczy T, Ippolito GC, Walkley CR, Maika SD, et al. Developmental and species-divergent globin switching are driven by BCL11A. Nature. 2009 Aug 27;460(7259):1093–1097. doi: 10.1038/nature08243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu J, Sankaran VG, Ni M, Menne TF, Puram RV, Kim W, et al. Transcriptional silencing of {gamma}-globin by BCL11A involves long-range interactions and cooperation with SOX6. Genes Dev. 2010 Apr 15;24(8):783–798. doi: 10.1101/gad.1897310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jawaid K, Wahlberg K, Thein SL, Best S. Binding patterns of BCL11A in the globin and GATA1 loci and characterization of the BCL11A fetal hemoglobin locus. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2010 Aug 15;45(2):140–146. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yi Z, Cohen-Barak O, Hagiwara N, Kingsley PD, Fuchs DA, Erickson DT, et al. Sox6 directly silences epsilon globin expression in definitive erythropoiesis. PLoS Genet. 2006 Feb;2(2):e14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dumitriu B, Patrick MR, Petschek JP, Cherukuri S, Klingmuller U, Fox PL, et al. Sox6 cell-autonomously stimulates erythroid cell survival, proliferation, and terminal maturation and is thereby an important enhancer of definitive erythropoiesis during mouse development. Blood. 2006 Aug 15;108(4):1198–1207. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-004184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cohen-Barak O, Erickson DT, Badowski MS, Fuchs DA, Klassen CL, Harris DT, et al. Stem cell transplantation demonstrates that Sox6 represses epsilon y globin expression in definitive erythropoiesis of adult mice. Exp Hematol. 2007 Mar;35(3):358–367. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dumitriu B, Bhattaram P, Dy P, Huang Y, Quayum N, Jensen J, et al. Sox6 is necessary for efficient erythropoiesis in adult mice under physiological and anemia-induced stress conditions. PLoS One. 2010 Aug 9;5(8):e12088. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuwata T, Nakamura T. BCL11A is a SUMOylated protein and recruits SUMO-conjugation enzymes in its nuclear body. Genes Cells. 2008 Sep;13(9):931–940. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2008.01216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chin J, Singh M, Banzon V, Vaitkus K, Ibanez V, Kouznetsova T, et al. Transcriptional activation of the gamma-globin gene in baboons treated with decitabine and in cultured erythroid progenitor cells involves different mechanisms. Exp Hematol. 2009 Oct;37(10):1131–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Singleton BK, Fairweather VSS, Lau W, Parsons SF, Burton NM, Frayne J, et al. A Novel EKLF Mutation in a Patient with Dyserythropoietic Anemia: The First Association of EKLF with Disease in Man. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts) 2009;114 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heruth DP, Hawkins T, Logsdon DP, Gibson MI, Sokolovsky IV, Nsumu NN, et al. Mutation in erythroid specific transcription factor KLF1 causes Hereditary Spherocytosis in the Nan hemolytic anemia mouse model. Genomics. 2010 Aug 5; doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Singleton BK, Burton NM, Green C, Brady RL, Anstee DJ. Mutations in EKLF/KLF1 form the molecular basis of the rare blood group In(Lu) phenotype. Blood. 2008 Sep 1;112(5):2081–2088. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-145672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Borg J, Papadopoulos P, Georgitsi M, Gutierrez L, Grech G, Fanis P, et al. Haploinsufficiency for the erythroid transcription factor KLF1 causes hereditary persistence of fetal hemoglobin. Nat Genet. 2010 Sep;42(9):801–805. doi: 10.1038/ng.630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou D, Liu K, Sun CW, Pawlik KM, Townes TM. KLF1 regulates BCL11A expression and gamma- to beta-globin gene switching. Nat Genet. 2010 Aug 1; doi: 10.1038/ng.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miller IJ, Bieker JJ. A novel, erythroid cell-specific murine transcription factor that binds to the CACCC element and is related to the Kruppel family of nuclear proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1993 May;13(5):2776–2786. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.5.2776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Orkin SH, Kazazian HH, Jr, Antonarakis SE, Goff SC, Boehm CD, Sexton JP, et al. Linkage of beta-thalassaemia mutations and beta-globin gene polymorphisms with DNA polymorphisms in human beta-globin gene cluster. Nature. 1982 Apr 15;296(5858):627–631. doi: 10.1038/296627a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gilman JG, Manca L, Frogheri L, Pistidda P, Guiso L, Longinotti M, et al. Mild beta+(-87)-thalassemia CACCC box mutation is associated with elevated fetal hemoglobin expression in cis. Am J Hematol. 1994 Mar;45(3):265–267. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830450316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Perkins AC, Sharpe AH, Orkin SH. Lethal beta-thalassaemia in mice lacking the erythroid CACCC-transcription factor EKLF. Nature. 1995 May 25;375(6529):318–322. doi: 10.1038/375318a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nuez B, Michalovich D, Bygrave A, Ploemacher R, Grosveld F. Defective haematopoiesis in fetal liver resulting from inactivation of the EKLF gene. Nature. 1995 May 25;375(6529):316–318. doi: 10.1038/375316a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guy LG, Mei Q, Perkins AC, Orkin SH, Wall L. Erythroid Kruppel-like factor is essential for beta-globin gene expression even in absence of gene competition, but is not sufficient to induce the switch from gamma-globin to beta-globin gene expression. Blood. 1998 Apr 1;91(7):2259–2263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Perkins AC, Gaensler KM, Orkin SH. Silencing of human fetal globin expression is impaired in the absence of the adult beta-globin gene activator protein EKLF. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996 Oct 29;93(22):12267–12271. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wijgerde M, Gribnau J, Trimborn T, Nuez B, Philipsen S, Grosveld F, et al. The role of EKLF in human beta-globin gene competition. Genes Dev. 1996 Nov 15;10(22):2894–2902. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.22.2894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Donze D, Townes TM, Bieker JJ. Role of erythroid Kruppel-like factor in human gamma- to beta-globin gene switching. J Biol Chem. 1995 Jan 27;270(4):1955–1959. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.4.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhou D, Pawlik KM, Ren J, Sun CW, Townes TM. Differential binding of erythroid Krupple-like factor to embryonic/fetal globin gene promoters during development. J Biol Chem. 2006 Jun 9;281(23):16052–16057. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601182200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Basu P, Lung TK, Lemsaddek W, Sargent TG, Williams DC, Jr, Basu M, et al. EKLF and KLF2 have compensatory roles in embryonic beta-globin gene expression and primitive erythropoiesis. Blood. 2007 Nov 1;110(9):3417–3425. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-057307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Perkins AC, Peterson KR, Stamatoyannopoulos G, Witkowska HE, Orkin SH. Fetal expression of a human Agamma globin transgene rescues globin chain imbalance but not hemolysis in EKLF null mouse embryos. Blood. 2000 Mar 1;95(5):1827–1833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hodge D, Coghill E, Keys J, Maguire T, Hartmann B, McDowall A, et al. A global role for EKLF in definitive and primitive erythropoiesis. Blood. 2006 Apr 15;107(8):3359–3370. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tallack MR, Whitington T, Yuen WS, Wainwright EN, Keys JR, Gardiner BB, et al. A global role for KLF1 in erythropoiesis revealed by ChIP-seq in primary erythroid cells. Genome Res. 2010 Aug;20(8):1052–1063. doi: 10.1101/gr.106575.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Eaton SA, Funnell AP, Sue N, Nicholas H, Pearson RC, Crossley M. A network of Kruppel-like Factors (Klfs). Klf8 is repressed by Klf3 and activated by Klf1 in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2008 Oct 3;283(40):26937–26947. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804831200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thein SL, Menzel S, Peng X, Best S, Jiang J, Close J, et al. Intergenic variants of HBS1L-MYB are responsible for a major quantitative trait locus on chromosome 6q23 influencing fetal hemoglobin levels in adults. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Jul 3;104(27):11346–11351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611393104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wahlberg K, Jiang J, Rooks H, Jawaid K, Matsuda F, Yamaguchi M, et al. The HBS1L-MYB intergenic interval associated with elevated HbF levels shows characteristics of a distal regulatory region in erythroid cells. Blood. 2009 Aug 6;114(6):1254–1262. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-210146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jiang J, Best S, Menzel S, Silver N, Lai MI, Surdulescu GL, et al. cMYB is involved in the regulation of fetal hemoglobin production in adults. Blood. 2006 Aug 1;108(3):1077–1083. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-008912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mucenski ML, McLain K, Kier AB, Swerdlow SH, Schreiner CM, Miller TA, et al. A functional c-myb gene is required for normal murine fetal hepatic hematopoiesis. Cell. 1991 May 17;65(4):677–689. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90099-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bianchi E, Zini R, Salati S, Tenedini E, Norfo R, Tagliafico E, et al. c-Myb supports erythropoiesis through the transactivation of KLF1 and LMO2 expression. Blood. 2010 Aug 4; doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-238311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.van der Ploeg LH, Flavell RA. DNA methylation in the human gamma delta beta-globin locus in erythroid and nonerythroid tissues. Cell. 1980 Apr;19(4):947–958. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Goren A, Simchen G, Fibach E, Szabo PE, Tanimoto K, Chakalova L, et al. Fine tuning of globin gene expression by DNA methylation. PLoS One. 2006 Dec 20;1:e46. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhao Q, Rank G, Tan YT, Li H, Moritz RL, Simpson RJ, et al. PRMT5-mediated methylation of histone H4R3 recruits DNMT3A, coupling histone and DNA methylation in gene silencing. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009 Mar;16(3):304–311. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rank G, Cerruti L, Simpson RJ, Moritz RL, Jane SM, Zhao Q. Identification of a PRMT5-dependent repressor complex linked to silencing of human fetal globin gene expression. Blood. 2010 May 21; doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-251116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Miccio A, Blobel GA. Role of the GATA-1/FOG-1/NuRD pathway in the expression of human beta-like globin genes. Mol Cell Biol. 2010 Jul;30(14):3460–3470. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00001-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Huang S, Litt M, Felsenfeld G. Methylation of histone H4 by arginine methyltransferase PRMT1 is essential in vivo for many subsequent histone modifications. Genes Dev. 2005 Aug 15;19(16):1885–1893. doi: 10.1101/gad.1333905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.van Dijk TB, Gillemans N, Pourfarzad F, van Lom K, von Lindern M, Grosveld F, et al. Fetal globin expression is regulated by Friend of Prmt1. Blood. 2010 Aug 5; doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-274399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chou S, Lodish HF. Fetal liver hepatic progenitors are supportive stromal cells for hematopoietic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 Apr 27;107(17):7799–7804. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003586107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Peschle C, Gabbianelli M, Testa U, Pelosi E, Barberi T, Fossati C, et al. C-Kit Ligand Reactivates Fetal Hemoglobin Synthesis in Serum-Free Culture of Stringently Purified Normal Adult Burst-Forming Unit-Erythroid. Blood. 1993 Jan 15;81(2):328–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bhanu NV, Trice TA, Lee YT, Gantt NM, Oneal P, Schwartz JD, et al. A sustained and pancellular reversal of gamma-globin gene silencing in adult human erythroid precursor cells. Blood. 2005 Jan 1;105(1):387–393. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sripichai O, Kiefer CM, Bhanu NV, Tanno T, Noh SJ, Goh SH, et al. Cytokine-mediated increases in fetal hemoglobin are associated with globin gene histone modification and transcription factor reprogramming. Blood. 2009 Sep 10;114(11):2299–2306. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-219386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gabbianelli M, Testa U, Morsilli O, Pelosi E, Saulle E, Petrucci E, et al. Mechanism of human Hb switching: a possible role of the kit receptor/miR 221-222 complex. Haematologica. 2010 Aug;95(8):1253–1260. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.018259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Koehler AN. A complex task? Direct modulation of transcription factors with small molecules. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2010 Jun;14(3):331–340. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ley TJ, DeSimone J, Anagnou NP, Keller GH, Humphries RK, Turner PH, et al. 5-Azacytidine Selectively Increases Gamma-Globin Synthesis in a Patient with Beta+ Thalassemia. N Engl J Med. 1982 Dec 9;307(24):1469–1475. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198212093072401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Perrine SP, Miller BA, Faller DV, Cohen RA, Vichinsky EP, Hurst D, et al. Sodium butyrate enhances fetal globin gene expression in erythroid progenitors of patients with Hb SS and beta thalassemia. Blood. 1989 Jul;74(1):454–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Skarpidi E, Cao H, Heltweg B, White BF, Marhenke RL, Jung M, et al. Hydroxamide derivatives of short-chain fatty acids are potent inducers of human fetal globin gene expression. Exp Hematol. 2003 Mar;31(3):197–203. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(02)01030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Witt O, Monkemeyer S, Ronndahl G, Erdlenbruch B, Reinhardt D, Kanbach K, et al. Induction of fetal hemoglobin expression by the histone deacetylase inhibitor apicidin. Blood. 2003 Mar 1;101(5):2001–2007. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bradner JE, Mak R, Tanguturi SK, Mazitschek R, Haggarty SJ, Ross K, et al. Chemical genetic strategy identifies histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) and HDAC2 as therapeutic targets in sickle cell disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 Jul 13;107(28):12617–12622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006774107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Aagaard L, Rossi JJ. RNAi therapeutics: principles, prospects and challenges. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2007 Mar 30;59(2-3):75–86. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dhanasekaran M, Negi S, Sugiura Y. Designer zinc finger proteins: tools for creating artificial DNA-binding functional proteins. Acc Chem Res. 2006 Jan;39(1):45–52. doi: 10.1021/ar050158u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hanna J, Wernig M, Markoulaki S, Sun CW, Meissner A, Cassady JP, et al. Treatment of sickle cell anemia mouse model with iPS cells generated from autologous skin. Science. 2007 Dec 21;318(5858):1920–1923. doi: 10.1126/science.1152092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wilber A, Tschulena U, Hargrove PW, Kim YS, Persons DA, Barbas CF, 3, et al. A zinc-finger transcriptional activator designed to interact with the gamma-globin gene promoters enhances fetal hemoglobin production in primary human adult erythroblasts. Blood. 2010 Apr 15;115(15):3033–3041. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-240556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]