Summary

Primordial germ cells (PGCs) undergo proliferation, invasion, guided migration, and aggregation to form the gonad. Here we show that in Drosophila, the receptor tyrosine kinase Torso activates both STAT and Ras during the early phase of PGC development, and coactivation of STAT and Ras is required for PGC proliferation and invasive migration. Embryos mutant for stat92E or Ras1 have fewer PGCs, and these cells migrate slowly, errantly, and fail to coalesce. Conversely, overactivation of these molecules causes supernumerary PGCs, their premature transit through the gut epithelium, and ectopic colonization. A requirement for RTK in Drosophila PGC development is analogous to the mouse, in which the RTK c-kit is required, suggesting a conserved molecular mechanism governing PGC behavior in flies and mammals.

Introduction

Germ cells of an animal are set aside as a distinct cell population early during embryogenesis to ensure transmission of genetic information to the next generation. These cells are in a sense immortal, as the germ cell lineage is passed from generation to generation, raising questions of how they are maintained and their development controlled. Primordial germ cells (PGCs) are morphologically distinct from somatic cells and are more motile, as they have to travel from their place of origin along and through other tissues to eventually colonize in the site of the gonad (reviewed by Kierszenbaum and Tres, 2001; Starz-Gaiano and Lehmann, 2001; Wylie, 1999, 2000). Interestingly, germ cells share similar behaviors with metastasizing cancer cells, namely, proliferation, invasive migration, and colonization, making germ cells an attractive model system to study molecular mechanisms that govern cell proliferation, migration, and invasion.

Drosophila PGCs are determined by maternally derived germ plasm (or pole plasm) that contains essential germ cell-specific components (reviewed by Starz-Gaiano and Lehmann, 2001; Wylie, 2000). In the first 2–3 hr of Drosophila embryogenesis, nuclei divide synchronously without cytokinesis in a syncytium (stage 1–4). Cellularization occurs as embryogenesis enters stage 5 after 13 rapid nuclear divisions. Prior to cellularization, during the eighth and ninth nuclear cycle (about stage 3), a few nuclei migrate to the posterior pole to form PGCs, which are also known as pole cells. These cells divide about two to three times independently and form 30–40 large cells by stage 5 and then cease mitosis. Afterward, PGCs move into the interior of the embryo and start their migration journey along a complex route to reach the somatic gonadal precursor cells (SGPs; reviewed by Starz-Gaiano and Lehmann, 2001; Wylie, 2000).

Studies of Drosophila PGCs have resulted in the identification of a number of genes essential for their specification and/or migration. The maternal gene product Oskar (Osk) plays an instructive role in specifying germ plasm assembly and PGC formation (Ephrussi and Lehmann, 1992). Vasa (Vas), an RNA helicase and translation initiation factor homolog, is involved in Osk translation and is a germ cell-specific marker in many organisms including mammals (Lasko and Ashburner, 1988; Starz-Gaiano and Lehmann, 2001). The maternal products and translation repressors Nanos (Nos) and Pumilio play roles in PGC migration, though the molecular mechanism remains obscure (Asaoka-Taguchi et al., 1999; Deshpande et al., 1999). On the other hand, several genes have been identified that act in somatic cells to influence the migration of PGCs. These genes include wunen, encoding the lipid phosphate phosphatase-1 homolog, and columbus, encoding an HMG-CoA reduc-tase (Van Doren et al., 1998; Zhang et al., 1997). The products of these genes are involved in lipid metabolism and are thought to be responsible for the production of spatial cues that guide PGC migration. In addition, it has recently been shown that Hedgehog (Hh), secreted from the somatic gonadal precursor cells, can serve as an attractive guidance cue for the migrating PGCs (Deshpande et al., 2001). In mice, the receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) and protooncoprotein c-kit and its ligand are required for germ cell proliferation and migration (reviewed by Besmer et al., 1993; Kierszenbaum and Tres, 2001). It has been shown that c-kit is expressed on the membrane of mouse PGCs, and its ligand is produced by somatic tissues and plays a role in guiding PGC migration (Kierszenbaum and Tres, 2001). However, no homologs of these molecules have been identified in the Drosophila genome. On the other hand, a mouse knockout of a wunen homolog did not result in discernible fertility defects (Zhang et al., 2000). Therefore, it has been unclear whether the molecular mechanisms underlying germ cell development and guided migration are shared among species.

Despite the findings of several somatic signals involved in guiding germ cell migration in Drosophila, little is known about the intrinsic mechanisms that coordinate changes in cytoskeleton and/or adhesion of PGCs during their migration and differentiation. Because PGCs share certain cellular properties with cancer cells, we wondered whether they also share common signaling strategies in controlling their behaviors. It is well known that signaling molecules such as Ras and STAT, when overactivated, can serve as oncoproteins to promote tumorigenesis and metastasis (reviewed by Bromberg, 2002; Shields et al., 2000). We speculated that germ cells might use these common signaling molecules to coordinate movements during their migratory journey.

We have focused our attention on the RTK Torso (Tor; reviewed by Duffy and Perrimon, 1994) because it is activated in the region of the early embryo where PGCs form and initiate migration. Furthermore, Tor activates both the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK (Ras1/Draf/Dsor/Rolled) signaling cassette and STAT92E (also known as Marelle; this study).

Here we show that in the early Drosophila embryo, in addition to activating its known downstream signaling targets, the Ras/Raf (Ras1/Draf) signaling cassette (reviewed by Duffy and Perrimon, 1994), Tor causes STAT92E activation. Further, we found that the coactivation of STAT92E and Ras1/Draf signaling persists in pole cells and is required for their initial mitotic divisions and, at later stages, their invasion, guided migration, survival, and adhesion. The identification of an RTK involved in Drosophila PGC development suggests evolutionary conservation between flies and mice in molecular mechanisms that regulate germ cell proliferation and migration. These results further suggest that germ cells and cancer cells might share certain similar intrinsic signaling strategies in controlling their behaviors.

Results

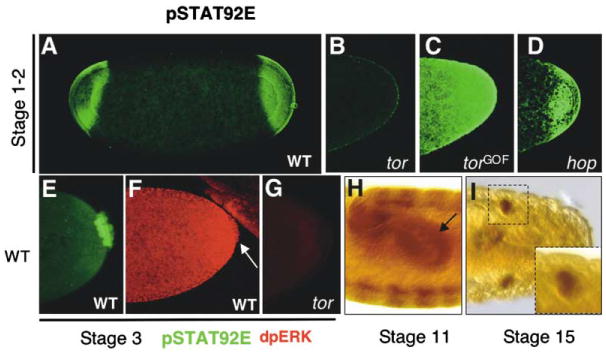

Tor Activates STAT92E in Early Embryos and Pole Cells

STAT92E plays an essential role in mediating the phenotypic effects of gain-of-function mutations of Tor, TorGOF, but is only minimally required for wild-type Tor function in patterning the terminal structures of the Drosophila embryo (Li et al., 2002). To investigate whether wild-type Tor nevertheless activates STAT92E, we used an antibody that recognizes the phosphorylated, or active form of STAT92E (pSTAT92E; Li et al., 2003) to examine the activation status of STAT92E in different genetic backgrounds. We found that in early embryos, pSTAT92E is detected in the anterior and posterior terminal regions in a pattern reminiscent of Tor activation (Figure 1A). By analyzing embryos mutant for loss- or gain-of-function mutations of tor as well as those lacking JAK (see Experimental Procedures), encoded by hopscotch (hop; Binari and Perrimon, 1994; Figures 1B–1D), we concluded that the early STAT92E activation is dependent on Tor but not Hop, suggesting that Tor may activate STAT92E independent of Hop. Because STAT92E contributes only marginally to the expression of the Tor target gene tailless (tll; Li et al., 2002), we wondered whether the early activation of STAT92E by Tor had any other biological functions. It was evident that Tor activation correlates temporally and spatially with the formation of PGCs, which are localized at the posterior pole of the early embryo. We found that Tor-dependent activation of STAT92E as well as that of the Ras-MAPK signaling cassette, as detected by an antibody against activated ERK/MAPK (diphospho-ERK), persists in pole cells at this stage (Figures 1E and 1F). We also detected STAT92E activation in PGCs during their migration (Figure 1H) and in the gonads of late embryos (Figure 1I), which are formed following the migration of pole cells through a complex route. These observations indicate that STAT92E and Ras1/Draf activation may play a role in PGC development.

Figure 1. STAT92E Activation by Tor and in Germ Cells.

Detection of STAT92E activation (A–E, H, and I) by anti-pSTAT92E antibody staining ([A–E], green; [H and I], brown) in embryos of indicated stages. Activation of the Ras-MAPK pathway was detected by an anti-dpERK antibody ([F and G], red).

(A) STAT92E activation is detected in the two polar regions in early stage wild-type embryos. This pattern is reminiscent of Tor activation.

(B) pSTAT92E staining is absent in embryos from tor homozygous females.

(C) torGOF embryos exhibit higher levels and broader domains of pSTAT92E staining.

(D) Wild-type pattern of pSTAT92E staining persists in hopmat− embryos.

(E) Detection of pSTAT92E in pole cells of early embryos.

(F and G) ERK/MAPK activation was detected in the posterior region and pole cells (arrow) in wild-type embryos (F). Such staining was absent in tor mutant embryos (G).

(H) STAT92E activation persists in pole cells (arrow) once inside the gut pocket, as well as in the gut epithelium and parasegments.

(I) In late embryos, pSTAT92E is strongly expressed in the gonad.

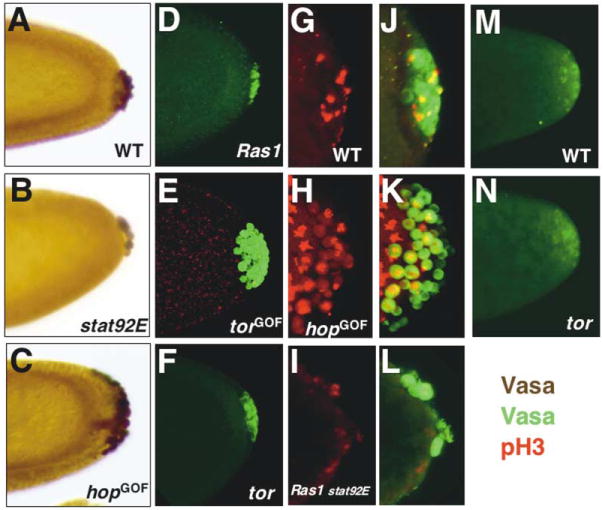

STAT and Ras Activation by Tor Is Involved in Regulating PGC Mitotic Divisions

To investigate the role of STAT92E and Ras1 coactivation in PGC development, we examined embryos lacking the maternal gene products of stat92E, Ras1, and hop (referred to respectively as stat92Emat−, Ras1mat−, and hopmat− embryos; see Experimental Procedures). We found that at the cellularization stage, stat92Emat−, Ras1mat−, and tor embryos had 20%–30% fewer pole cells when compared with wild-type embryos (Figures 2B, 2D, and 2F; Table 1). Simultaneous removal of maternal product in stat92Emat− and Ras1mat− had an even more dramatic effect on pole cell numbers, resulting in a 54% reduction (Figure 2L; Table 1). This indicates that STAT92E and Ras1 activation may play an important role in the initial pole cell mitotic divisions. Consistent with this interpretation, we found that embryos harboring a gain-of-function mutation in hop or tor (hopGOF or torGOF, respectively; see Experimental Procedures) had nearly twice as many pole cells as wild-type (Figures 2C, 2E, and 2K; Table 1). These results suggest that both the Ras1/Draf and STAT92E pathways are involved in the initial mitotic divisions of the pole cells. Such mitotic defects were not observed in hopmat− embryos (Table 1), consistent with the observation that Tor, not Hop, activates STAT92E in precellularization stage embryos.

Figure 2. Effects of STAT92E and Ras1 Activation on Pole Cell Number and Division.

Pole cells were identified by Vas expression ([A–C], brown; [E and F and J–L], green). Mitotic cells were identified by pH3 staining ([G–L], red). Representative cellularization stage (stage 5) embryos of wild-type (A), stat92Emat− (B), hopGOF (C), Ras1mat− (D), torGOF (E), and tor (F) are shown. Propidium iodide staining ([E], red) was used to visualize the nuclei. Representative embryos stained for pH3 are shown for wild-type (G and J), hopGOF (H and K), and Ras1 stat92E double maternal null mutant (I and L).

(M and N) Initial pole cell formation in nuclear cycle 9 embryos.

(M) In wild-type embryos, early Vas-positive pole cells begin “budding” at nuclear cycle 9. Some of them will form pole cells.

(N) Vas staining and pole cell budding were normal in tor embryos.

Table 1. Germ Cell Number and Mitosis in Early and Late Embryos.

| Cellularization Stage Embryo | Stage 14 Embryo | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | Pole Cell Number ± SD | p Value | Number of pH3-Positive Pole Cells ± SD | p Value | Total Number of Germ Cells in the Embryo ± SD | p Value |

| WT | 32.8 ± 5.2 | – | 4.50 ± 1.9 | – | 16.2 ± 3.7 | – |

| stat92E | 23.0 ± 4.9 | 0.001 | 2.17 ± 1.7 | 0.05 | 12.8 ± 3.8 | 0.08 |

| Ras1 | 21.5 ± 6.3 | 0.002 | 1.67 ± 1.6 | 0.02 | 7.3 ± 2.6 | 0.001 |

| Ras1 stat92E | 15.1 ± 5.4 | 2.6 × 10−5 | 1.33 ± 1.5 | 0.01 | ND | – |

| tor | 25.7 ± 4.4 | 0.02 | ND | – | 0.8 ± 1.2 | 2.8 × 10−6 |

| hop | 29.7 ± 6.6 | 0.35 | ND | – | ND | – |

| tor GOF | 57.4 ± 11 | 0.0008 | ND | – | ND | – |

| hopGOF | 62.0 ± 8.9 | 1.4 × 10−6 | 9.83 ± 3.3 | 0.001 | 32.0 ± 9.1 | 0.001 |

SD, standard deviation; ND, not determined; p value is calculated by Student's t test; p < 0.05 indicates a significant difference. More than ten embryos were counted for each genotype or stage. Genotypes indicate maternal mutations.

To confirm that the changes in the pole cell number observed in different mutant embryos result from altered pole cell division rates, we examined the levels of phosphohistone H3 (pH3), which is present only in mitotic cells (Hendzel et al., 1997). Indeed, we found a decrease in the number of pole cells positive for pH3 in precellularization stage embryos mutant for stat92Emat− or Ras1mat−, as well as in those of stat92Emat− Ras1mat− double mutants (Figures 2D, 2F, and 2I; Table 1). Pole cells of stat92Emat− Ras1mat− double mutant embryos appeared slightly larger than wild-type pole cells (Figure 2I), consistent with their slower division rate. Conversely, hopGOF embryos had many more pH3-positive pole cells and these cells were smaller, presumably because they divided faster (Figure 2H; Table 1). Moreover, we found these mutations did not affect initial pole cell formation, such that Vas staining in the posterior region and the number of pole cell “buds” forming were normal in early stat92Emat−, Ras1mat−, and tor embryos (see Figures 2M and 2N for tor). Taken together, the above results demonstrate that both signaling branches, Ras1/Draf and STAT92E, downstream of Tor are involved in the initial mitotic divisions of PGCs.

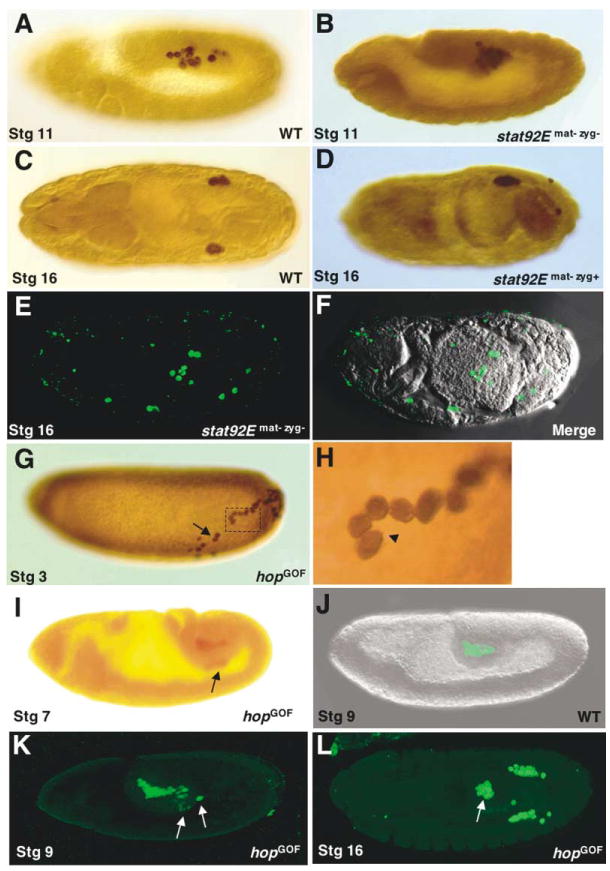

Role of STAT Activation in Primordial Germ Cell Migration

Because STAT92E has been shown to play a role in the migration of ovarian border cells during oogenesis (Beccari et al., 2002; Silver and Montell, 2001), we investigated whether STAT92E might also be required for the migration of PGCs. Indeed, we found that germ cell migration in stat92Emat− embryos was affected at multiple stages. At stage 11, when wild-type germ cells have migrated out of the gut pocket and have become associated with the dorsal mesoderm, germ cells in stat92Emat− embryos were still associated with the gut and appeared slow in migrating into the dorsal mesoderm (Figures 3A and 3B). Many (23/38) late stat92Emat− embryos that received a paternal copy of stat92E+ (stat92Emat−zyg+ or paternally rescued stat92Emat− embryos) were missing one gonad, while the remaining gonad contained more germ cells than wild-type (Figures 3C and 3D), indicating that the PGCs might have failed to bifurcate properly when migrating out of the gut. In embryos that were missing both the maternal and zygotic copy of stat92E (stat92Emat−zyg−), no gonads were formed, and the PGCs were scattered randomly in the cavity of the late embryo (Figures 3E and 3F), indicating that these cells had failed to migrate and coalesce properly.

Figure 3. Effects of STAT92E Mutation or Overactivation on Germ Cell Migration.

PGCs were identified by Vas expression (brown or green staining). At stage 11, wild-type PGCs (A) migrate to dorsal mesoderm; PGCs of stat92Emat−zyg− embryos (B) are still associated with the gut. At stage 16, wild-type PGCs (C) coalesce to form two laterally located gonads (with about ten germ cells in each) in abdominal segment 5 (A5); paternally rescued stat92Emat− embryos (D) often have only one gonad with more than ten germ cells (the gonad shown in [D] has 18 germ cells). (E and F) stat92Emat−zyg− embryos that did not receive the paternal zygotic copy of stat92E+ show errant migration of germ cells and these cells fail to coalesce to form gonads.

The effects of STAT92E overactivation on germ cell migration were analyzed using hopGOF embryos. Arrows indicate stray or ectopic PGCs. (G) At stage 3, some pole cells in hopGOF embryos migrate away from the posterior pole. The locations of wild-type pole cells at this stage are shown in Figure 2A.

(H) High magnification of dotted area in (A) shows migrated hopGOF pole cells exhibit amoeboid shape, some extending cellular processes (arrowhead).

(J) Wild-type pole cells are confined within the pocket of the posterior midgut up to stage 9. From as early as stage 7 (I) until stage 9 (K), pole cells of hopGOF embryos penetrate the gut epithelium (arrow).

(L) The PGCs in hopGOF embryos that had gone astray coalesce at ectopic sites (arrow).

In hopGOF embryos, where STAT92E is overactivated, the germ cells appeared more mobile in addition to being more numerous. At stage 4-5, when wild-type pole cells are confined to the posterior pole, the pole cells in some hopGOF embryos had migrated away (Figures 3G and 3H). During gastrulation, when the posterior midgut invaginates, hopGOF germ cells were frequently observed to prematurely transit through the gut and migrate errantly (Figures 3I–3K). In wild-type embryos, errant germ cells are eliminated by apoptosis (reviewed by Williamson and Lehmann, 1996). The PGCs of hopGOF embryos that had gone astray survived and aggregated in ectopic locations (Figure 3L; Table 1). These results demonstrate an essential requirement for STAT92E activation in the migration, survival, and colonization of PGCs.

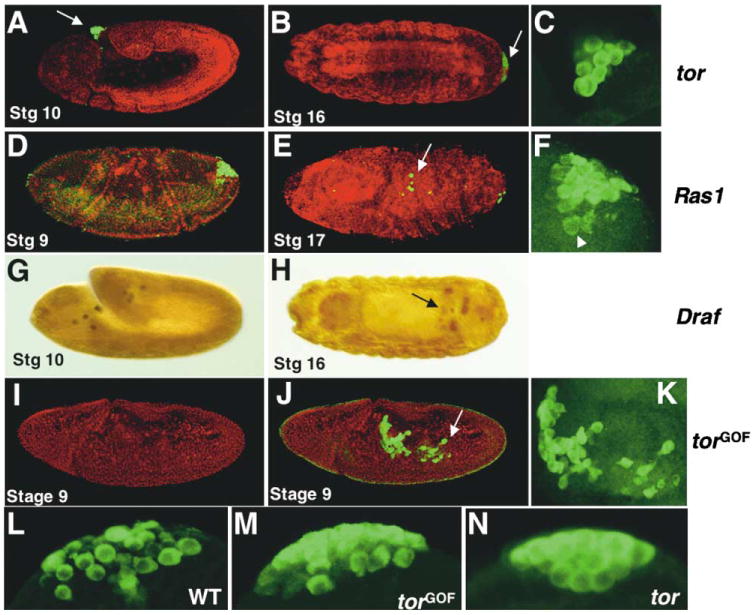

Coactivation of STAT and Ras/Raf Signaling in PGC Migration

To assess whether the Tor-Ras1 branch of the pathway is also required for pole cell migration, we examined embryos lacking the maternal products of tor, Ras1, and Draf (see Experimental Procedures). The most severe pole cell migration defects, when the pole cells were completely motionless, were observed in embryos from tor homozygous females (referred to as tor embryos; Figures 4A and 4C). In contrast to wild-type pole cells that are internalized during gastrulation, pole cells of the vast majority of tor embryos (93/98) did not enter the embryo at all during gastrulation and were left outside of it by the end of embryogenesis (Figures 4A and 4B). This finding is in contrast to a previous report (Warrior, 1994) of tor and trunk (trk; encoding a Tor ligand; Casanova et al., 1995) mutant embryos, which states a substantially higher number of trk mutant pole cells that entered the embryo. The failure of tor mutant pole cells to enter the embryo could be due to the defective gastrulation and posterior midgut invagination associated with tor embryos, in which the posterior midgut primordium is completely missing (Klingler et al., 1988; also see Figure 4A; reviewed by St Johnston and Nusslein-Volhard, 1992). Alternatively, pole cells may actively migrate prior to the invagination of the posterior midgut. Consistent with the latter interpretation, we found that pole cells indeed appeared to start migrating, judging from cell shape changes (see below), at the cellularization stage (stage 4) prior to gastrulation. In precellularization stage wild-type embryos, the pole cells assumed a spherical shape (not shown). However, at the end of cellularization and the beginning of gastrulation, the cells at the periphery of the pole cell cluster notably changed shape from perfectly spherical to irregular and elongated, some extending pseudopodia (Figure 4L). In addition, some of these cells appeared to start moving away from the cluster, as the pole cell cluster appeared more scattered at this stage (Figure 4L) than in the earlier stages, when they were tightly packed (not shown). More extensive shape changes or scattering movements were observed in torGOF (Figure 4M) and, especially, hopGOF embryos (Figures 3G and 3H). In contrast, no obvious shape changes were observed in the pole cells of tor embryos (Figure 4N). These pole cells remained spherical and tightly packed at all times, even in the late stage embryos (see Figures 4A and 4C for stage 10). The observation that pregastrulation stage pole cells actively migrate runs contrary to the notion that pole cells are merely passively swept into the midgut pocket at the start of gastrulation (see review by Starz-Gaiano and Lehmann, 2001). However, our observations are consistent with those by Jaglarz and Howard (1995), who reported that extensive shape changes and actin cytoskeleton rearrangements occur in pole cells at the onset of gastrulation, such that many of them extend pseudopodia (see Figure 1 in Jaglarz and Howard, 1995).

Figure 4. Effects of Mutations in tor, Ras1, and Draf on Germ Cell Migration.

PGCs were identified by their positive staining with an anti-Vas antibody (green or brown staining). Propidium iodide staining (red) was used to assist identifying the morphology. Arrows indicate abnormally located PGCs. In embryos from tor homozygous females, the PGCs do not enter the embryo during gastrulation (A) and are left outside of it in late embryos (B).

(C) Higher magnification of the PGCs in (A). Note these cells remained spherical in shape. In embryos that lack maternal Ras1 (D–F) or Draf (G and H), some PGCs enter the embryo but fail to migrate or coalesce to form gonads.

(F) Higher magnification of the PGCs in (G) showing these cells are capable of changing shape and penetrating the epithelium (arrowhead indicates a PGC found underneath the epidermal epithelium). In torGOF embryos (I and J), the PGCs migrate out of the posterior midgut prematurely. They appear more abundant and motile, some extending long projections (see [K] for higher magnification). At cellularization and the start of gastrulation, wild-type (L) and, to a greater extent, torGOF (M) pole cells change shape and extend pseudopodia, while tor (N) pole cells remain spherical.

To further test the hypothesis that coactivation of Ras and STAT by Tor is essential for initial pole cell migration, we examined Ras1mat− or Drafmat− embryos that are defective in the Tor-Ras1/Draf branch of signaling but retain normal Tor-STAT92E signaling, as evidenced by normal pSTAT92E staining in Ras1mat− or Drafmat− embryos (not shown). Similar to tor embryos, Ras1mat− or Drafmat− embryos exhibit defective gastrulation and lack the posterior midgut primordium (Figures 4D and 4G). However, in contrast to those of tor embryos, the pole cells of Ras1mat− or Drafmat− embryos appeared to be slightly more motile, such that some of the pole cells were able to transit through the epithelia and were present inside the embryo at late embryogenesis (Figures 4E and 4H). Indeed, unlike the spherical pole cells of tor embryos, those in Ras1mat− embryos, though the majority of them remained outside the embryo, became amoeboid during gastrulation, and some of them were found underneath the epidermis (arrowhead in Figure 4F), indicating that they might have penetrated the epithelium. The differential initial migration phenotypes exhibited by tor and Ras1mat− or Drafmat− mutants suggest that both pathways downstream of Tor play roles in pole cell mobility, such that in the absence of Tor-Ras1/Draf signaling, STAT92E activation by Tor may confer certain mobility on the pole cells. Conversely, in torGOF embryos, in which both STAT92E and Ras1/Draf are overactivated, the PGCs appeared more mobile and abundant, behaving similarly to hopGOF embryos (Figures 4J and 4K). Late torGOF embryos, however, appeared normal with regard to gonad formation (not shown), presumably due to the diminished tor expression in later stages (Casanova and Struhl, 1989; Sprenger et al., 1989) and elimination of the errant germ cells by apoptosis. Therefore, the initial PGC migration and their ability to penetrate epithelia require the activation of both STAT92E and Ras1/Draf signaling by Tor at the posterior pole.

In addition to defects in the initial penetration, the PGCs in Ras1mat− or Drafmat− embryos, once having entered the embryo, appeared abnormal in both the directed migration and aggregation and were found randomly scattered in the embryonic cavity (Figures 4E and 4H). Moreover, generally very few PGCs were found in late Ras1mat− or Drafmat− embryos (Figures 4E and 4H; Table 1) and some of them appeared to be fragmenting (not shown), suggesting that some PGCs may have died. This is consistent with the finding that the Ras1/Draf pathway promotes cell survival (Bergmann et al., 1998; Kurada and White, 1998). These results suggest that, similar to STAT92E, Ras1/Draf signaling is essential for the directed migration, survival, and colonization of PGCs.

Cell-Autonomous Effects of Ras1 and STAT92E Signaling on PGC Behavior

Because PGC migration anomalies could result from developmental defects in the somatic gonadal precursors cells (SGPs), we therefore examined the somatic gonads of stat92E and Ras1 mutant embryos using an antibody against the gonadal mesoderm-specific marker Clift (Cli; Boyle et al., 1997). We found the early mesodermal expression of Cli is normal in stage 11 stat-92Emat−zyg+, stat92Emat−zyg−, and Ras1mat−zyg+ embryos. At later stages, SGPs expressing nuclear Cli, albeit at lower levels, were identifiable in stat92Emat−zyg− and Ras-1mat−zyg+ embryos (see Supplemental Data at http://www.developmentalcell.com/cgi/content/full/5/5/787/DC1), suggesting that SGP formation in these embryos is mostly normal. However, because SGPs may not be the sole determinant of germ cell migration, their presence cannot rule out the possibility that mutant somatic tissues exert nonautonomous effects on germ cell migration.

To further determine whether the different morphological and migratory properties of the pole cells exhibited by different mutants are intrinsic to these cells, that is, are cell autonomous, or are indirect effects of mutant somatic tissues, we first studied the behavior of isolated pole cells free of somatic tissues in culture medium and then followed the fate of mutant pole cells transplanted into a wild-type host and vice versa.

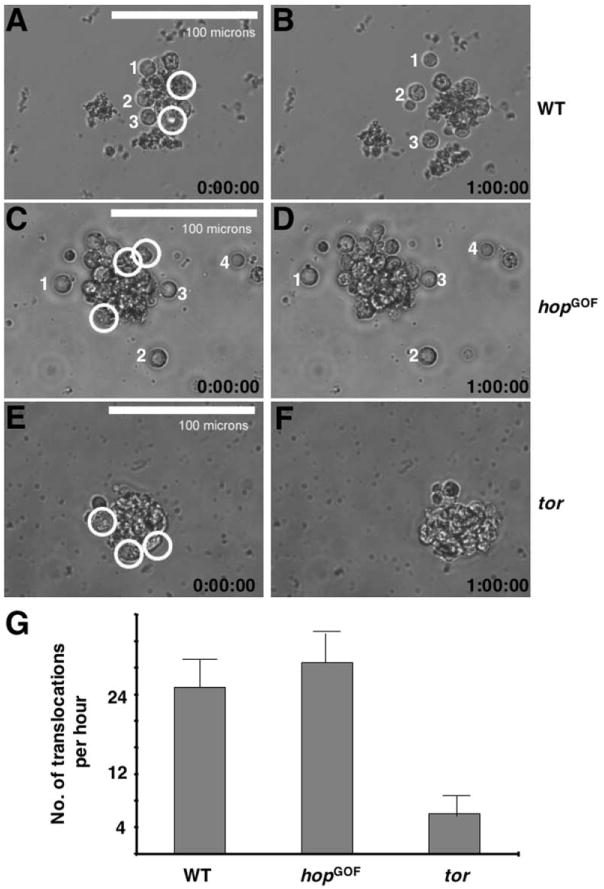

It has previously been reported that Drosophila PGCs can be cultured for a period of time in medium and still remain functional (Allis et al., 1979; Jaglarz and Howard, 1995). We removed cellularization stage pole cells from wild-type embryos as well as those from hopGOF and tor embryos, which appeared the most and least motile, respectively (see Figures 3G, 3H, and 4A–4C), and observed these cells in Schneider culture medium (see Experimental Procedures).

The isolated pole cells initially remained associated with each other and formed a cluster in culture medium, as they were at the posterior pole of the embryo. However, after a period of time, a few cells at the edge of the pole cell cluster would dissociate and disperse (numbered in Figures 5A–5D; see Supplemental Data). In addition, a few cells still attached to the cluster would engage in back and forth amoeboid movements, which we termed translocation movements (circled in Figures 5A, 5C, and 5E; see Supplemental Data). Consistent with our observation of pole cells in fixed embryos, we found those isolated from hopGOF embryos were more active both in dispersion and translocation movements, whereas those from tor embryos hardly disperse and were slow in the translocation movements (Figure 5G; see Supplemental Data). These observations support the conclusion that intrinsic signaling, rather than surrounding somatic tissues, plays an essential role in initial pole cell movement.

Figure 5. Behavior of Pole Cells In Vitro.

(A–F) The first and last frames from a time-lapse analysis of in vitro cultured PGCs of wild-type (A and B), hopGOF (C and D), and tor (E and F) embryos. Wild-type and, to a greater extent, hopGOF pole cells appeared more active in dispersing (numbered cells) and engaging in translocation movements (circled cells). See Supplemental Movies 1–3 for more detail.

(G) Quantification of translocation movements of in vitro cultured PGCs of indicated genotypes.

Next, we investigated the development of stat92E, Ras1, and tor mutant germ cells in a wild-type environment by pole cell transplantation. We extracted pole cells from stage 4 (cellularization stage) embryos mutant for the maternal stat92E, Ras1, and tor genes as well as from wild-type control embryos and deposited these pole cells into stage 4–6 wild-type host embryos. When the operated host embryos developed into adult flies, we examined the phenotypes of their progeny to determine whether any of them were derived from donor germ cells (see Experimental Procedures).

We performed three sets of pole cell transplantation experiments. In control experiments using wild-type donor pole cells, we recovered a total of 21 mosaic flies that produced offspring derived from transplanted wild-type donor germ cells. In contrast, five, zero, and seven mosaic flies were recovered following pole cell transplantation using stat92E, Ras1, and tor maternal mutant donor pole cells, respectively (Supplemental Table S1, column 5), suggesting that these mutant germ cells had a much reduced success rate of incorporating into wild-type gonads. Examination of progeny phenotypes revealed that all the five mosaic flies recovered from transplanting stat92E pole cells were the offspring of transplanted stat92Emat−zyg+ pole cells with a stat92E/TM3 genotype (Supplemental Table S1, column 6). These results indicate that in a wild-type environment, stat92Emat−zyg−, Ras1mat−zyg−, and Ras1mat−zyg+ germ cells were unable to migrate to wild-type somatic gonadal tissues, and stat92Emat−zyg+ and tor germ cells were much less efficient in such a migration compared with wild-type germ cells.

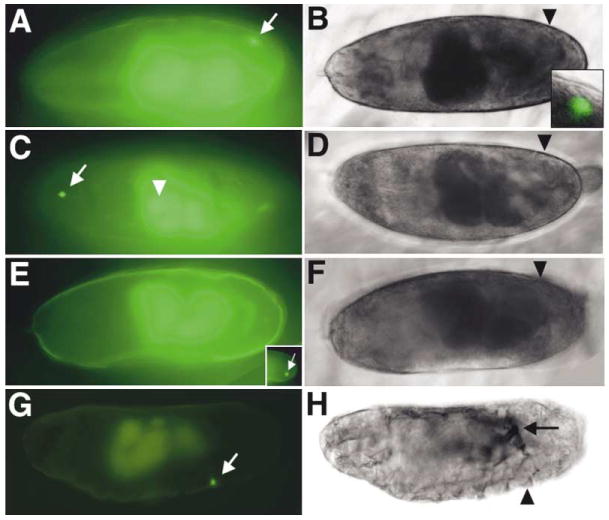

To observe the actual migration of transplanted germ cells of different genotypes in live wild-type and mutant host embryos, we labeled the donor pole cells with fluorescein-dextran before transplanting them into host embryos (see Experimental Procedures). In control experiments, transplanted wild-type germ cells migrated along the characteristic route and ended up in the gonad of late stage host embryos in eight out of ten successful transplantation operations (see Figures 6A and 6B for an example). In contrast, out of ten successful transplantation operations, only one stat92E and no Ras1 maternally mutant germ cells were found in the gonad of late stage embryos. Both stat92E and Ras1 mutant germ cells were seen to migrate to ectopic locations (see Figures 6C–6F for examples). Interestingly, most of the Ras1 mutant germ cells that were present after transplantation disappeared in late stage embryos, possibly due to cell death. Therefore, stat92E and Ras1 mutant germ cells exhibited defects in migration toward the somatic gonad, and Ras1 mutant germ cells additionally survived poorly.

Figure 6. Migration of Transplanted Pole Cells in Wild-Type and tor Host.

(A, C, E, and G) Images of transplanted fluo-rescein-dextran-labeled wild-type (A and G), stat92E (C), or Ras1 (E) maternally mutant germ cells (green; indicated by white arrows or arrowhead) in stage 16 live wild-type (A, C, and E) and tor (G) host embryos. The gut appears green due to autofluorescence. (B, D, F, and H) Phase contrast images of the same embryos as shown in the left panel. Black arrowheads indicate the position of one gonad.

(A and B) A wild-type germ cell was incorporated into the gonad of the wild-type host. Inset shows a higher magnification of the gonad, which contains host germ cells (unlabeled) and one transplanted germ cell (green).

(C and D) Transplanted stat92E maternally mutant germ cells migrated to ectopic positions. One was found in the anterior (arrow) and another in the midgut (arrowhead; out of focus).

(E and F) Transplanted Ras1 maternally mutant germ cells died in a wild-type host and thus disappeared from the late stage host embryo. Inset shows the presence of a labeled germ cell in the same embryo at an earlier stage.

(G and H) A transplanted wild-type germ cell migrated normally in a tor host embryo. The arrow in (H) points to a broken tracheal trunk, typical of tor mutant embryos.

Finally, to assess the contribution of somatic tissues to germ cell migration, we transplanted wild-type pole cells into tor mutant host embryos. Out of ten successful operations, we observed in seven cases at least one donor germ cell migrated to the position of the somatic gonad (see Figures 6G and 6H for an example), suggesting the tor mutant soma can provide a normal environment for germ cell migration.

Taken together, the above results are consistent with a scenario in which both STAT92E and the Ras-MAPK pathway are required for the complex series of movements of PGCs. It appears that Tor is responsible for STAT92E and Ras1/Draf coactivation during the early stages of embryogenesis. Because Tor is only transiently expressed in early embryos (Casanova and Struhl, 1989; Sprenger et al., 1989), PGCs must respond to guidance cues by other mechanisms for their subsequent migration out of the gut and translocation to the sites of future gonads.

Guidance Cues of PGC Migration

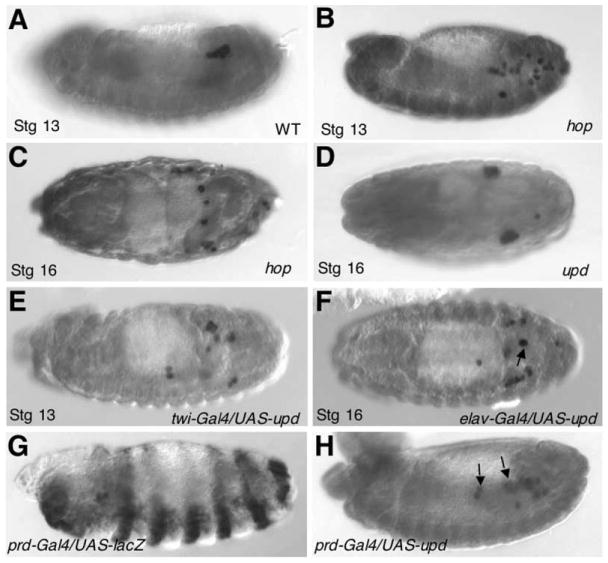

To investigate the guidance cues for the migrating germ cells, we tested the effects of mutations in hop and unpaired (upd), which encodes an extracellular ligand that triggers Hop/STAT92E signaling (Harrison et al., 1998) on PGC migration. First, we found that hopmat− embryos were normal in the initial pole cell migration (not shown), consistent with the notion that Tor, not Hop, is responsible for STAT92E activation in early embryos. However, in late stage hopmat− embryos, the PGCs failed to coalesce and/or to form gonads (cf. Figures 7A and 7B; Figures 7C and 3C). The late stage PGC defects in hopmat− embryos may be explained by the lack of STAT92E in these embryos, as STAT92E is not expressed or is greatly diminished in hopmat− embryos (J.L. et al., unpublished data; also see Chen et al., 2002). The onset of germ cell defects observed in hopmat− embryos occurred later than those in stat92Emat− embryos. While the PGCs of stat92Emat− embryos were sluggish in their transit through the posterior midgut and migration toward the dorsal mesoderm (see Figure 3B), those in hopmat− embryos appeared normal in traversing the gut epithelium and guided migration into the dorsal mesoderm (not shown). This suggests that some factors in addition to Hop may activate STAT92E at this stage. Tor can be ruled out because it is no longer expressed at this stage of development (Casanova and Struhl, 1989; Sprenger et al., 1989). Second, consistent with the above analysis indicating Hop may not be entirely responsible for STAT92E activation, we observed much milder germ cell migration defects in upd homozygous embryos. Despite the fact that upd mutant embryos exhibit identical segmentation defects to stat92Emat− or hopmat− embryos (Harrison et al., 1998), the PGCs of upd mutant embryos were able to migrate normally and coalesce to form a pair of gonads in late embryos. However, one of the gonads was often found to be located one segment offset from its proper location (Figure 7D). These results suggest that the secreted ligand Upd may provide part of the guidance cue for PGC migration yet is not solely responsible for guiding germ cell migration or activating STAT92E.

Figure 7. Effects of Mutations in hop and upd on Germ Cell Migration and Aggregation.

(A–C) Wild-type PGCs coalesce starting from stage 13 on each side the embryo (A); the PGCs in embryos lacking the maternal hop product fail to coalesce at stage 13 (B) and do not form gonads (C).

(D) The PGCs in embryos homozygous for upd are able to form gonads but they are often slightly mislocalized (one segment offset).

(E) Misexpression of Upd by the twist-Gal4 driver disrupted directed PGC migration.

(F) When Upd is expressed in the CNS by the elav-Gal4 driver, some PGCs were found in the nerve cord (arrow).

(G) Expression pattern (in alternate segments) of UAS-lacZ under prd-Gal4 control as detected by an anti-β-gal antibody.

(H) In embryos in which Upd was misexpressed by prd-Gal4, ectopic PGCs (arrows) were found in alternate segments.

In order to study whether PGCs might respond to diffusible ligands secreted from somatic sources, we tested the effects of misexpressing the Hop/STAT92E ligand Upd on PGC migration using the Gal4/UAS system (Brand and Perrimon, 1993). Consistent with the finding that STAT92E activation is essential for guided PGC migration, misexpression of upd caused PGC migration defects. Expressing a UAS-upd transgene by a twist-Gal4 driver, which directs expression in the mesoderm of early embryos, significantly altered PGC migration pattern (migration defects were seen in 67/81 embryos), such that instead of clustering in abdominal segments 4–7, these germ cells aggregated in small groups and were found in ectopic locations (cf. Figures 7A and 7E). To test whether misexpression of upd is sufficient to attract PGCs to ectopic locations, we used late-expressing Gal4 drivers such as elav-Gal4, which is expressed in neurons, and prd-Gal4, which drives expression in alternate segments (Figure 7G). Misexpression of upd using elav-Gal4 and prd-Gal4 drivers severely disrupted normal PGC migration in 93% (n = 109) and 96% (n = 91) of the embryos, respectively (not shown). Moreover, in some embryos, PGCs were found in places consistent with where ectopic upd is expressed, such that in elav-Gal4/UAS-upd embryos, they were found in the nerve cord (Figure 7F), and in prd-Gal4/UAS-upd embryos, many were found in alternate segments (Figure 7H). These results are consistent with a hypothesis that PGCs follow spatial cues provided by somatic tissues that secret ligands triggering STAT92E and/or Ras1/Draf activation, and disruption of the guidance cues, such as by misexpressing the ligand Upd, would alter the path of PGC migration.

Discussion

The behavior of germ cells during animal development bears certain similarity to that of cancer cells. Both types of cells have to proliferate, invade other tissues, survive, and aggregate to form a tissue mass. Drosophila germ cell migration provides an excellent model system to genetically dissect the mechanisms underlying the complex behavioral patterns of these cells. Our finding that STAT and Ras/Raf coactivation is essential for multiple aspects of germ cell behavior suggests that germ cells and cancer cells share not only behaviors but also the intrinsic signaling mechanisms.

The Drosophila RTK Tor is required for patterning the embryonic anterior and posterior terminal regions (reviewed by Duffy and Perrimon, 1994). So far the only known function of Tor has been in pattern formation, as Tor protein is present only transiently in early embryos (Casanova and Struhl, 1993; Sprenger and Nusslein-Volhard, 1992; Stevens et al., 1990). Therefore, our finding that Tor is involved in germ cell migration was initially unexpected. However, there is a precedent for the requirement of an RTK in germ cell migration in the mouse. Mutations in the mouse genes dominant white-spotting (W; Chabot et al., 1988) and Steel (Sl; Godin et al., 1991; Matsui et al., 1991) cause migration and proliferation defects in germ cells as well as a few other cell types (reviewed by Besmer et al., 1993; Kierszenbaum and Tres, 2001). W encodes the protooncoprotein c-kit, an RTK that is expressed on the membrane of mouse PGCs. Sl encodes the c-kit ligand termed stem cell factor (SCF), which is localized on the membrane of somatic cells associated with PGC migratory pathways (Kierszen-baum and Tres, 2001). Interestingly, c-kit and Tor share structural similarities and both are structurally similar to the platelet derived growth factor (PDGF) receptor, in which an insert region separates the intracellular kinase domain. Moreover, similar to Tor and the PDGF receptor, c-kit is able to activate STAT molecules (Brizzi et al., 1999; Deberry et al., 1997; Ning et al., 2001) as well as the Ras-MAPK cascade (De Miguel et al., 2002). Although true molecular homologs of c-kit and SCF were not yet found in the Drosophila genome, the functional and structural similarities between Tor and c-kit suggest that flies and mice share molecular mechanisms for regulating primordial germ cell proliferation and migration.

In addition to germ cells, the ovarian border cells of Drosophila are also capable of invasive and guided migration. Border cells of the Drosophila ovary are follicle cells that, during oogenesis, delaminate as a cluster six to ten cells from the anterior follicle epithelium, invade the nurse cells, and migrate toward the oocyte. Interestingly, it has been shown that the detachment and guided migration of these cells require STAT92E activation (Beccari et al., 2002; Ghiglione et al., 2002; Silver and Montell, 2001). Mutations in components of the Hop/STAT92E pathway cause border cell migration defects (Beccari et al., 2002; Silver and Montell, 2001). On the other hand, border cell migration also requires RTK signaling (Duchek et al., 2001). An RTK related to mammalian PDGF and VEGF receptors, PVR, is required in border cells for their guided migration toward the oocyte. PVR appears functionally redundant with another fly RTK, EGFR, in guiding border cells (Duchek et al., 2001). Taken together, these results indicate that the invasive behavior and guided migration of Drosophila ovarian border cells require both STAT92E and RTK activation. In light of our results from analyzing PGC migration, we propose that activation of both STAT and components downstream of RTK signaling may serve as a general mechanism for invasive and guided cell migration.

It has been shown that actin-based cytoskeletal reorganization plays a crucial role in cell shape changes and movements. The identification of STAT and Ras coactivation as an essential requirement for germ cell migration raised an interesting question of how activated STAT and Ras coordinate the cytoskeletal reorganization required for germ cell migration. STAT92E has been shown to be involved in the transcriptional activation of many signaling molecules as well as key transcription factors (Hou et al., 2002; Li et al., 2002; Luo and Dearolf, 2001; Silver and Montell, 2001). A recent systematic search for STAT92E target genes has revealed a plethora of genes that might be directly activated by STAT92E, among which are those involved in the regulation of cytoskeletal movements and actin reorganization (F.X. and W.X.L., unpublished data). Upregulation of such genes in response to spatial cues should facilitate cell movements. On the other hand, Ras and other small GTP proteins have been implicated in multiple cellular processes that require cytoskeletal reorganization. It remains to be determined how these two signaling pathways coordinate germ cell movements in response to guidance cues from surrounding somatic tissues.

Experimental Procedures

Fly Strains and Genetics

The following strong or null alleles were used in this study: torXR1 (Sprenger et al., 1989), Ras1ΔC40B (Hou et al., 1995), Draf11-29 (Ambrosio et al., 1989), stat92E6346 or mrl6346 (Hou et al., 1996), hopC111 (Binari and Perrimon, 1994), and updYM55 (Harrison et al., 1998). The gain-of-function (GOF) alleles used in this study are torY9 and torRL3 (Klingler et al., 1988) and hopTumL (Harrison et al., 1995). The dominant female sterile (DFS) technique (Chou and Perrimon, 1992) was employed to generate GLC embryos that lack the maternal product of Ras1, Draf, stat92E, and hop. For example, to produce stat92Emat− embryos, y w hs-Flp/w; FRT82B[ovoD1, w+]/TM3 males were crossed to FRT82Bstat92E6346/TM3 females. Third instar larvae were subjected to heat shock for 2 hr daily. Adult y w hs-Flp/+; FRT82Bstat92E6346/FRT82B[ovoD1, w+] females were collected for production of stat-92Emat− embryos. Embryos lacking the maternal products of both Ras1 and stat92E were produced in a similar fashion using a Ras1ΔC40Bstat92E6346 recombinant chromosome. Embryos lacking the maternal tor product were produced by torXR1/torXR1 females. Embryos produced by torXR1/torXR1 females exhibited germ cell and segmentation defects that were indistinguishable from those produced by torXR1/Df(2R)NCX8 females. We therefore used torXR1/torXR1 in this study. Heterozygous flies of updYM55/FM7 were used to analyze the zygotic mutant phenotypes of upd. When necessary, a “green balancer” (from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center) was used to recognize the wild-type chromosome in a collection of embryos. To produce GOF phenotypes, torY9/+ (kept at 18°C) or torR13/torR13(kept at 29°C), and hopTumL/+ (kept at 25°C) females were used to collect torGOF and hopGOF embryos, respectively.

Immunohistochemistry

Rabbit anti-Vas (kindly provided by Drs. Paul Lasko and Ruth Lehmann; 1:2000), mouse anti-Clift (eya10H6; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank; 1:50), and rabbit anti-pSTAT92E (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.; 1:1000) were used as primary antibodies for whole-mount immunostaining of embryos. For fluorescent immunostaining, embryos were further stained with an Alexa 488-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (Molecular Probes) and analyzed with Leica confocal microscopy. For DIC microscopy, the primary antibody was detected by a biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody and the ABC Elite kit (Vector Labs) with DAB solution according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The embryos stained with the ABC kit were dehydrated with ethanol, mounted with Euparal (ASCO Laboratories), and photographed with an Axiophot microscope.

PGC In Vitro Culture and Observation

Dechorionated cellularization stage embryos (stage 4) were ruptured by forceps to release the pole cells into Drosophila Schneider's medium (GIBCO) supplemented with L-glutamine, 10% bovine serum, and penicillin/streptomycin. The pole cells were allowed to settle on laminin-coated culture dishes (Becton Dickinson Labware) filled with the medium mentioned above at 25°C. The cells were observed and recorded at room temperature with phase contrast optics and imaging equipment. The images were recorded every 5 s for 1 hr total time. At least three movies were recorded for each genotype.

Pole Cell Transplantation

The pole cell transplantation procedure is essentially as described in Van Deusen (1976) with minor modifications. Dechorionated and properly desiccated host and donor embryos were lined up pairwise on a strip of double-sticky tape at the edge of a coverslip and were covered with halocarbon oil 400 (Sigma). A siliconized glass micropipet with a 45° opening at the tip was used to transfer pole cells. The pipet tip was filled with halocarbon oil and was operated by a syringe system.

Host embryos were produced by crossing virgin Oregon R (wild-type) females to ovoD1/Y males, such that the female host embryos were heterozygous for ovoD1, a germline-specific dominant female-sterile mutation (Perrimon and Gans, 1983). The use of ovoD1 mutation ensures that only the transplanted germ cells will develop into eggs in a host female, thus facilitating the examination of transplanted germ cells. Donor pole cells were from eggs produced by the following parental genotypes. For wild-type control, eggs laid by y w flies were collected. For tor, eggs laid by torXR1b pr cn bw homozygotes were used. For stat92E maternal mutant pole cells, y w hs-Flp/y w; FRT82B stat92E6346/FRT82B [ovoD1, w+] females were crossed to y w/Y; FRT82B stat92E6346/TM3 males. For Ras1 maternal mutant pole cells, y w hs-Flp/y w; FRT82B Ras1ΔC40B/FRT82B [ovoD1, w+] females were crossed to y w/Y; FRT82B Ras1ΔC40B/TM3 males. These females had been heat shocked during larval growth to induce clones of germ cells homozygous for the stat29E or Ras1 mutation. The resulting embryos were maternally mutant for stat29E or Ras1. These embryos were either paternally rescued or both maternal and paternal null for stat92E and Ras1 depending on whether they received a paternal mutant or wild-type copy of stat92E and Ras1 (on the TM3 balancer chromosome), respectively.

Pole cells were taken from stage 4 embryos of the above genotypes and were deposited into a host embryo using the transfer pipet. Following pole cell transplantation, operated host embryos were kept at 18°C for better recovery and the hatched larvae were transferred to a food vial for further growth. Surviving adults (both males and females) were individually test-crossed to y w flies, or, for the tor experiment, to torXR1b pr cn bw flies. Germline mosaic females (in ovoD1 heterozygous background) were those that laid eggs. Mosaic males were identified as those that produced y w female offspring, because the host male embryos were y+ w+/Y in genotype. The genotype of the donor egg was determined either by cuticle phenotypes (when there were dead embryos) or the presence of balancer chromosome or recessive markers (for surviving adults).

To observe the migration of transplanted pole cells in a host embryo, we used the methods essentially described in Jaglarz and Howard (1994) and transplanted fluorescein-labeled donor pole cells. To label donor pole cells, stage 2-3 embryos were injected at the posterior pole with fluorescein-dextran (1 mg/ml; Mr 70,000; Molecular Probes). Following cellularization, pole cells from these embryos, which contain fluorescein-dextran in the cytoplasm, were taken and transplanted into stage 4–6 host embryos as described above. Up to five donor pole cells were transplanted each time. The migration of transplanted germ cells (labeled with fluorescein-dextran) in live host embryos was observed on a Zeiss Axiophot microscope with fluorescent optics, and images were photographed when necessary. Germ cell migration was defined as successful if one or more of the transplanted germ cells was incorporated into the host gonad.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Healani Calhoun for technical assistance, Drs. P. Lasko and R. Lehmann for providing anti-Vasa antibodies, and Dr. N. Perrimon, the Bloomington Stock Center, and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for various fly strains and antibodies. We also thank Drs. Dirk Bohmann, Vladic Mogila, and Hucky Land and members of the Li lab for comments on the manuscript. J.L. is a recipient of the Wilmot Cancer Research Fellowship from the James P. Wilmot Foundation. This study was supported by a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Research Resources Program grant (#53000237) and a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01 GM65774) to W.X.L.

References

- Allis CD, Underwood EM, Caulton JH, Mahowald AP. Pole cells of Drosophila melanogaster in culture. Normal metabolism, ultrastructure, and functional capabilities. Dev Biol. 1979;69:451–465. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(79)90304-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosio L, Mahowald AP, Perrimon N. Requirement of the Drosophila raf homologue for torso function. Nature. 1989;342:288–291. doi: 10.1038/342288a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asaoka-Taguchi M, Yamada M, Nakamura A, Hanyu K, Kobayashi S. Maternal Pumilio acts together with Nanos in germline development in Drosophila embryos. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:431–437. doi: 10.1038/15666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beccari S, Teixeira L, Rorth P. The JAK/STAT pathway is required for border cell migration during Drosophila oogenesis. Mech Dev. 2002;111:115–123. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00615-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann A, Agapite J, McCall K, Steller H. The Drosophila gene hid is a direct molecular target of Ras-dependent survival signaling. Cell. 1998;95:331–341. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81765-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besmer P, Manova K, Duttlinger R, Huang EJ, Packer A, Gyssler C, Bachvarova RF. The kit-ligand (steel factor) and its receptor c-kit/W: pleiotropic roles in gametogenesis and melanogenesis. Dev Suppl. 1993:125–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binari R, Perrimon N. Stripe-specific regulation of pair-rule genes by hopscotch, a putative Jak family tyrosine kinase in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1994;8:300–312. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.3.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle M, Bonini N, DiNardo S. Expression and function of clift in the development of somatic gonadal precursors within the Drosophila mesoderm. Development. 1997;124:971–982. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.5.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand AH, Perrimon N. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development. 1993;118:401–415. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brizzi MF, Dentelli P, Rosso A, Yarden Y, Pegoraro L. STAT protein recruitment and activation in c-Kit deletion mutants. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:16965–16972. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.24.16965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromberg J. Stat proteins and oncogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1139–1142. doi: 10.1172/JCI15617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova J, Struhl G. Localized surface activity of torso, a receptor tyrosine kinase, specifies terminal body pattern in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1989;3:2025–2038. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.12b.2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova J, Struhl G. The torso receptor localizes as well as transduces the spatial signal specifying terminal body pattern in Drosophila. Nature. 1993;362:152–155. doi: 10.1038/362152a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova J, Furriols M, McCormick CA, Struhl G. Similarities between trunk and spatzle, putative extracellular ligands specifying body pattern in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2539–2544. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.20.2539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabot B, Stephenson DA, Chapman VM, Besmer P, Bernstein A. The proto-oncogene c-kit encoding a trans-membrane tyrosine kinase receptor maps to the mouse W locus. Nature. 1988;335:88–89. doi: 10.1038/335088a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HW, Chen X, Oh SW, Marinissen MJ, Gutkind JS, Hou SX. mom identifies a receptor for the Drosophila JAK/STAT signal transduction pathway and encodes a protein distantly related to the mammalian cytokine receptor family. Genes Dev. 2002;16:388–398. doi: 10.1101/gad.955202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou TB, Perrimon N. Use of a yeast site-specific recombinase to produce female germline chimeras in Drosophila. Genetics. 1992;131:643–653. doi: 10.1093/genetics/131.3.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deberry C, Mou S, Linnekin D. Stat1 associates with c-kit and is activated in response to stem cell factor. Biochem J. 1997;327:73–80. doi: 10.1042/bj3270073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Miguel MP, Cheng L, Holland EC, Federspiel MJ, Donovan PJ. Dissection of the c-Kit signaling pathway in mouse primordial germ cells by retroviral-mediated gene transfer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:10458–10463. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122249399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande G, Calhoun G, Yanowitz JL, Schedl PD. Novel functions of nanos in downregulating mitosis and transcription during the development of the Drosophila germline. Cell. 1999;99:271–281. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81658-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande G, Swanhart L, Chiang P, Schedl P. Hedgehog signaling in germ cell migration. Cell. 2001;106:759–769. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00488-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchek P, Somogyi K, Jekely G, Beccari S, Rorth P. Guidance of cell migration by the Drosophila PDGF/VEGF receptor. Cell. 2001;107:17–26. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00502-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy JB, Perrimon N. The torso pathway in Drosophila: lessons on receptor tyrosine kinase signaling and pattern formation. Dev Biol. 1994;166:380–395. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ephrussi A, Lehmann R. Induction of germ cell formation by oskar. Nature. 1992;358:387–392. doi: 10.1038/358387a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiglione C, Devergne O, Georgenthum E, Carballes F, Medioni C, Cerezo D, Noselli S. The Drosophila cytokine receptor Domeless controls border cell migration and epithelial polarization during oogenesis. Development. 2002;129:5437–5447. doi: 10.1242/dev.00116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godin I, Deed R, Cooke J, Zsebo K, Dexter M, Wylie CC. Effects of the steel gene product on mouse primordial germ cells in culture. Nature. 1991;352:807–809. doi: 10.1038/352807a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison DA, Binari R, Nahreini TS, Gilman M, Perrimon N. Activation of a Drosophila Janus kinase (JAK) causes hematopoietic neoplasia and developmental defects. EMBO J. 1995;14:2857–2865. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07285.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison DA, McCoon PE, Binari R, Gilman M, Perrimon N. Drosophila unpaired encodes a secreted protein that activates the JAK signaling pathway. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3252–3263. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.20.3252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendzel MJ, Wei Y, Mancini MA, Van Hooser A, Ranalli T, Brinkley BR, Bazett-Jones DP, Allis CD. Mitosis-specific phosphorylation of histone H3 initiates primarily within pericentromeric heterochromatin during G2 and spreads in an ordered fashion coincident with mitotic chromosome condensation. Chromosoma. 1997;106:348–360. doi: 10.1007/s004120050256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou XS, Chou TB, Melnick MB, Perrimon N. The torso receptor tyrosine kinase can activate Raf in a Ras-independent pathway. Cell. 1995;81:63–71. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90371-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou XS, Melnick MB, Perrimon N. Marelle acts downstream of the Drosophila HOP/JAK kinase and encodes a protein similar to the mammalian STATs. Cell. 1996;84:411–419. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81286-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou SX, Zheng Z, Chen X, Perrimon N. The Jak/STAT pathway in model organisms. Emerging roles in cell movement. Dev Cell. 2002;3:765–778. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00376-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaglarz MK, Howard KR. Primordial germ cell migration in Drosophila melanogaster is controlled by somatic tissue. Development. 1994;120:83–89. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaglarz MK, Howard KR. The active migration of Drosophila primordial germ cells. Development. 1995;121:3495–3503. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.11.3495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kierszenbaum AL, Tres LL. Primordial germ cell-somatic cell partnership: a balancing cell signaling act. Mol Reprod Dev. 2001;60:277–280. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingler M, Erdelyi M, Szabad J, Nusslein-Volhard C. Function of torso in determining the terminal anlagen of the Drosophila embryo. Nature. 1988;335:275–277. doi: 10.1038/335275a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurada P, White K. Ras promotes cell survival in Drosophila by downregulating hid expression. Cell. 1998;95:319–329. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81764-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasko PF, Ashburner M. The product of the Drosophila gene vasa is very similar to eukaryotic initiation factor-4A. Nature. 1988;335:611–617. doi: 10.1038/335611a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li WX, Agaisse H, Mathey-Prevot B, Perrimon N. Differential requirement for STAT by gain-of-function and wild-type receptor tyrosine kinase Torso in Drosophila. Development. 2002;129:4241–4248. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.18.4241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Li W, Calhoun HC, Xia F, Gao FB, Li WX. Patterns and functions of STAT activation during Drosophila embryogenesis. Mech Dev. 2003 doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2003.09.004. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo H, Dearolf CR. The JAK/STAT pathway and Drosophila development. Bioessays. 2001;23:1138–1147. doi: 10.1002/bies.10016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui Y, Toksoz D, Nishikawa S, Williams D, Zsebo K, Hogan BL. Effect of Steel factor and leukaemia inhibitory factor on murine primordial germ cells in culture. Nature. 1991;353:750–752. doi: 10.1038/353750a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning ZQ, Li J, McGuinness M, Arceci RJ. STAT3 activation is required for Asp(816) mutant c-Kit induced tumorigenicity. Oncogene. 2001;20:4528–4536. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrimon N, Gans M. Clonal analysis of the tissue specificity of recessive female-sterile mutations of Drosophila melanogaster using a dominant female-sterile mutation Fs(1)K1237. Dev Biol. 1983;100:365–373. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90231-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields JM, Pruitt K, McFall A, Shaub A, Der CJ. Understanding Ras: ‘it ain’t over ‘til it's over’. Trends Cell Biol. 2000;10:147–154. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01740-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver DL, Montell DJ. Paracrine signaling through the JAK/STAT pathway activates invasive behavior of ovarian epithelial cells in Drosophila. Cell. 2001;107:831–841. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00607-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprenger F, Nusslein-Volhard C. Torso receptor activity is regulated by a diffusible ligand produced at the extracellular terminal regions of the Drosophila egg. Cell. 1992;71:987–1001. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90394-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprenger F, Stevens LM, Nusslein-Volhard C. The Drosophila gene torso encodes a putative receptor tyrosine kinase. Nature. 1989;338:478–483. doi: 10.1038/338478a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starz-Gaiano M, Lehmann R. Moving towards the next generation. Mech Dev. 2001;105:5–18. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00392-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens LM, Frohnhofer HG, Klingler M, Nusslein-Volhard C. Localized requirement for torso-like expression in follicle cells for development of terminal anlagen of the Drosophila embryo. Nature. 1990;346:660–663. doi: 10.1038/346660a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St Johnston D, Nusslein-Volhard C. The origin of pattern and polarity in the Drosophila embryo. Cell. 1992;68:201–219. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90466-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Deusen EB. Sex determination in germ line chimeras of Drosophila melanogaster. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1976;37:173–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Doren M, Broihier HT, Moore LA, Lehmann R. HMG-CoA reductase guides migrating primordial germ cells. Nature. 1998;396:466–469. doi: 10.1038/24871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warrior R. Primordial germ cell migration and the assembly of the Drosophila embryonic gonad. Dev Biol. 1994;166:180–194. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson A, Lehmann R. Germ cell development in Drosophila. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1996;12:365–391. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wylie C. Germ cells. Cell. 1999;96:165–174. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80557-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wylie C. Germ cells. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2000;10:410–413. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00105-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N, Zhang J, Purcell KJ, Cheng Y, Howard K. The Drosophila protein Wunen repels migrating germ cells. Nature. 1997;385:64–67. doi: 10.1038/385064a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N, Sundberg JP, Gridley T. Mice mutant for Ppap2c, a homolog of the germ cell migration regulator wunen, are viable and fertile. Genesis. 2000;27:137–140. doi: 10.1002/1526-968x(200008)27:4<137::aid-gene10>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.