Introduction

In the modern era of highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART), a leading cause of death in HIV-infected persons is liver disease, most often due to chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection [1]. Approximately one quarter of HIV infected persons have chronic hepatitis C [2], and HIV-HCV co-infected persons have demonstrated a more rapid progression of liver disease compared with HCV mono-infected persons. Although the mechanism(s) are not fully known, liver disease is more severe in those with more profound CD4+ lymphocyte depletion compared to those with preserved peripheral blood CD4+ lymphocyte counts [3–8].

HIV induced depletion of intestinal CD4+ lymphocytes [9–12] has recently been linked to microbial translocation and HIV progression [13]. Moreover, in a cohort of HCV-infected persons at different stages of liver disease we have shown that microbial translocation in HIV co-infected persons was strongly associated with liver disease progression [14]. In that study we also found that HIV seroconversion amongst HCV-infected persons was associated with an increase in microbial translocation over time. It is, therefore, compelling to consider microbial translocation as a common mechanism that contributes to both HIV and HCV progression. Interestingly, animal models of other forms of liver disease have demonstrated a critical role of intestinal microbial translocation in promoting fibrosis [15–20].

Hepatic macrophages, or Kupffer cells, are responsible for clearing microbial translocation products and play a role in liver disease. Kupffer cells, however, can be infected by HIV, and this may result in their impaired ability to clear these potentially fibrogenic microbial translocation products [21–27]. In this investigation, we tested the hypotheses that Kupffer cell quantities are associated with peripheral CD4+ lymphocyte count in HIV-HCV co-infection, and that changes in CD4+ due to antiretroviral therapy are associated with corresponding alterations in Kupffer cell quantities. In addition, since in chronic viral hepatitis fibrosis begins in the portal and periportal regions where microbial translocation products first enter the liver, we tested the hypothesis that Kupffer cells would be most abundant in these regions.

Methods

The study population derives from the HIV-HCV co-infected members of the Johns Hopkins University clinical cohort (Baltimore, MD) [3;28]. Seventy-six individuals were identified who had at least two archived liver tissue samples and correlated clinical data characterizing HIV and HCV stage between January, 1997 and February, 2005. All subjects provided written informed consent for testing through a protocol approved by the Committees on Human Research of the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine or Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Data on clinical and lab parameters were abstracted from the clinical and laboratory databases. Transcutaneous liver biopsies were obtained using an 18-gauge needle. Liver tissue was fixed in 10% formalin and paraffin-embedded. Tissues were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) as well as trichrome. As previously described, tissues were scored by an experienced liver pathologist (M.T.) for fibrosis according to the Metavir scoring system for HCV infection and were graded for the degree of inflammation by using the Ishak modified hepatic activity index (MHAI) [29]. Hepatic fat (steatosis) was assessed as an average percentage of fat (0, 1–30, 31–60, > 60%) on H&E section. The pathologist was blinded to the subjects’ clinical history and laboratory values. In a select group of subjects who were studied longitudinally, slides obtained from the same subject were separately encoded and de-identified before handling by the pathologist. Adequacy of tissue size was determined by the pathologist and subjects with inadequate tissues were excluded from the investigation. The median length of tissues was 12 mm. To detect Kupffer cells, tissue sections were immunostained following heat antigen retrieval with mouse monoclonal anti-CD68 antibodies (Dako, Carpinteria, CA), used at a 1:100 dilution. The DAKO EnVision+ Peroxidase kit was used for immunostaining. Kupffer cells were identified by their strong cytoplasmic staining. Kupffer cell density (KCD) was determined as the arithmetic mean number of Kupffer cells per 5 high power fields. Portal and periportal Kupffer cells were further quantified and compared with centrilobular Kupffer cells. [To detect CD68+/HLA-DRα+ Kupffer cells, paraffin-embedded tissue sections from 20 available liver blocks were selected from a subset of subjects matched for MHAI score who had liver biopsies obtained at a second time point. Blocks were deparaffinized and sequentially immunostained with the anti-CD68+ antibody followed by a rabbit polyclonal anti-HLA-DRα IgG antibody (Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA), both at 1:100 dilution. Dual sequential immunostaining was performed using the EnVision G|2 Doublestain System (Dako, Carpinteria, CA). CD68+/ HLA-DRα-, and CD68−/ HLA-DRα+, and CD68+/HLA-DRα+ cells were enumerated in 5–10 parenchymal high powered fields and averaged.]

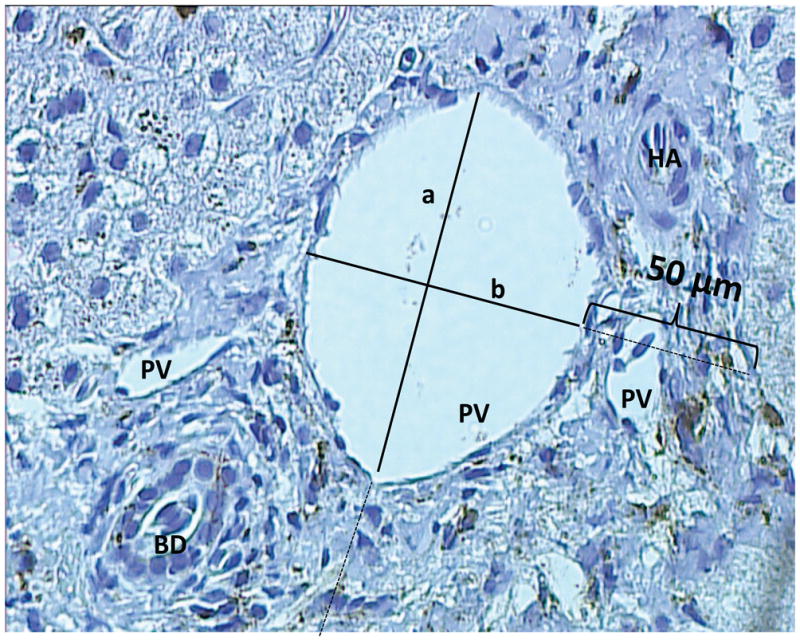

Regional differences in KCD were characterized by quantifying all CD68+ Kupffer cells within a 50 μm radius of selected portal and centrilobular veins. A Zeiss PALMR MicroLaser system was used to accurately determine a 50 μm radius around vessels. While this distance extends from portal to periportal regions depending on the section, it allows for precise comparisons between portal and centrilobular Kupffer cells. Cases were selected for analysis if they had at least one suitable complete cross section of both a well oriented portal tract and central vein. To avoid skewed results on the basis of oversampling regions of abundant inflammation, only 1 representative portal or centrilobular vein was used from a cluster of branching vessels. Multiple sequential sections were only used to confirm findings, and not used for counting to avoid oversampling the same cells. Kupffer cell number was normalized per μm2 to account for differences in vessel size using the adapted area of an elliptical ring, π *(½ a + 50)*(½ b + 50) − π*(½ a)* (½ b), where a and b were the measured long and short axes of the vessel in μm (Fig. 1). Kupffer cell counts of zero were conservatively assigned values of 0.5 per given area as the lower limit of detection. Results are reported in mm2.

Fig.1.

PV - portal vein; BD - bile duct; HA - hepatic artery; KC - Kupffer cell. Shown is a representative picture of a portal triad, taken with a 20X light microscope. Kupffer cells are CD68 stained and appear brown on a counterstained blue background. A 50 μm designation was used to quantify Kupffer cells in an elliptical donut surrounding an hepatic vessel. Kupffer cells/mm2 were defined by (No. of Kupffer cells*1000) / [π(½a+50)(½b+50)- π(½a)(½b)].

Liver biopsies were obtained a median (range) of 1.25 (0.1 – 139.6) months from the assessment of CD4+ lymphocyte count and clinical data, which were also ascertained using structured instruments before and after the initial liver biopsy, as described elsewhere [28]. KCD in all subjects was approximately normally distributed. Wilcoxon rank-sum and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to compare median KCD values across different covariates of interest. Linear regression models were used to model the association between KCD and both current and nadir CD4+ lymphocyte count. Kupffer cell quantities per vessel were not normally distributed and were compared using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. When log-transformed, Kupffer cell quantities per vessel yielded normally distributed data that was similarly found to be statistically significant using paired t tests.

Results

Seventy-six HIV-HCV co-infected persons with archived liver biopsies were identified. The mean age of the participants was 44.8 years at the time of the first biopsy, 59 (77.6%) were male, and 67 (88.2%) were African-American (Table 1). Peripheral blood CD4+ lymphocyte counts ranged from 9 to 1277/mm3 and serum HIV RNA ranged from undetectable to > 400,000 copies per mL. Antiretroviral therapy use was reported in 57 (75%) persons. All persons had chronic HCV infection with a median RNA level of 596,000 IU/mL. HCV infection was predominantly genotype 1a (66.2%) or 1b (25.4%).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 76 HIV-HCV co-infected subjects.

| Characteristics | N (%) | Median KCD | IQR | p valuef |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agea | ||||

| <40 years | 17 (22.4) | 24.4 | 17.4 – 30.2 | 0.48 |

| 40 – 50 years | 40 (52.6) | 23 | 18 – 26.8 | - |

| ≥ 50 years | 19 (25) | 21.2 | 16. – 26.2 | - |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 59 (77.6) | 22.8 | 17.4 – 27.6 | 0.48 |

| Female | 17 (22.4) | 24.4 | 18.4 – 29.6 | - |

| Race | ||||

| Black | 67 (88.2) | 23.4 | 18 – 28.6 | 0.25 |

| All others | 9 (11.8) | 20.8 | 14.2 – 23 | - |

| HCV Genotype | ||||

| 1a | 47 (66.2) | 23 | 17.4 – 29.4 | 0.76 |

| 1b | 18 (25.2) | 23.2 | 19 – 24.8 | - |

| CD4+ T cell countb | ||||

| < 350/mm3 | 39 (51.3) | 20.8 | 14.2 – 24.7 | 0.03 |

| ≥ 350/mm3 | 37 (48.7) | 24.4 | 21.2 – 28.6 | - |

| HIV Viral RNAc | ||||

| < 400 cp/mL | 42 (55.3) | 23 | 18 – 26.2 | 0.51 |

| ≥ 400 cp/mL | 34 (44.7) | 23.1 | 14.4 – 30.4 | |

| HAARTd | ||||

| Yes | 53 (69.7) | 22 | 14.4 – 27.6 | 0.10 |

| No | 23 (30.3) | 24.4 | 19 – 31 | - |

| Metavire | ||||

| < 2 | 67 (88.2) | 23.2 | 18 – 28 | 0.63 |

| ≥ 2 | 9 (11.8) | 20.8 | 16.2 – 27.4 | - |

| MHAIe | ||||

| ≤ 5 | 61 (80.3) | 22.4 | 18 – 25.2 | 0.28 |

| > 5 | 9 (11.8) | 25.7 | 18.4 – 32.2 | - |

HAART - highly active anti-retroviral therapy.

Age is given at the time of the first biopsy.

CD4+ lymphocyte determinations were made within a median (range) of 1.25 (0.1 – 139.6) months of the first biopsy.

HIV viral RNA was determined within a median (range) of 1.50 (0.1 – 68.9) months of the first biopsy.

HAART was defined as use of at least 2 nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI) + 1 protease inhibitor (PI), or 2 NRTIs +1 non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI), or 2 NRTIs + 1 NNRTI.

Metavir and MHAI staging were determined by liver biopsy by a trained pathologist (M.T.)

p values were generated from Wilcoxon rank-sum and Kruskal-Wallis tests.

Baseline liver fibrosis stage ranged from zero to cirrhosis (Metavir 0–4). Liver inflammation ranged from MHAI 0 to 9, and steatosis from 0 to 60%. KCD was normally distributed over the cohort, with a median (IQR) of 23 cells/HPF (17.7–27.8). No differences were detected in the KCD distribution according to age, gender, or HCV genotype (Table 1). Importantly, peripheral blood monocyte (Kupffer cell precursors) quantity was not associated with KCD (p=0.25). KCD was also not associated with liver disease fibrosis stage on the concurrent or subsequent biopsy, and was not associated with grade of hepatic inflammation or steatosis.

Mean KCD was significantly lower in subjects with lower peripheral blood CD4+ lymphocyte counts compared to those with higher levels (p<0.05, by Wilcoxon rank-sum test). KCD was associated with both contemporaneous CD4+ lymphocyte count and the lowest result recorded before histologic sampling (nadir CD4+ count, Table 2).

Table 2.

Independent association of Kupffer cell density with CD4+ lymphocyte count.a

Shown are univariate models of Kupffer cell density.

CD4+ lymphocyte determinations were made within a median (range) of 1.3 (0.1 – 139.6) months of the first biopsy.

Nadir CD4+ lymphocyte count was determined within a median (range) of 17.3 (0.1 – 139.6) months before the first biopsy, and was defined as the lowest recorded CD4+ lymphocyte count available.

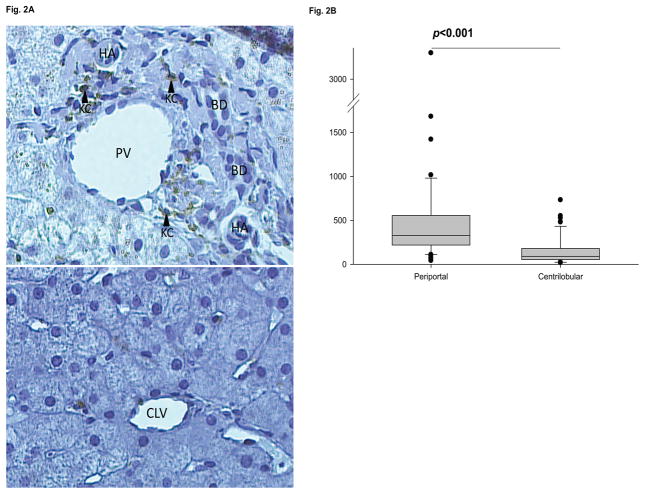

Since microbial translocation products enter the liver through the portal vein, we examined whether Kupffer cells were distributed more heavily in portal and periportal regions than centrilobular regions, as has been seen in rats [30;31]. From the 76 archived liver biopsies, 51 cases had sufficient tissue for additional analysis. There were no significant differences in the clinical characteristics between subjects with adequate liver tissue for the regional analysis and those with insufficient tissue. In total, Kupffer cells from 122 portal and 95 centrilobular regions were counted. The median (range) number of portal and periportal Kupffer cells, 328.6 (41.4 – 3252.8) /mm2 , was markedly higher than for centrilobular Kupffer cells, 90.5 (18.2 – 731.9) /mm2 (Fig. 2A, B).

Fig. 2.

A. PV - portal vein; BD - bile duct; HA - hepatic artery; CLV - centrilobular vein; KC - Kupffer cell. Shown are representative pictures of a portal triad (upper panel) and a centrilobular vein (lower panel) from the same individual, taken with a 20X light microscope. Kupffer cells are CD68 stained and appear brown on a counterstained blue background. B. Biopsies from 51/76 subjects with ≥ 1 postal vein and ≥1 centrilobular vein were evaluated for a total of 122 portal and 95 centrilobular veins. Kupffer cells were quantified as described. Groups were compared using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests.

[Quiescent Kupffer cells are normally immunotolerant to physiologic amounts of microbial translocation. In order to determine if progression of AIDS was associated with Kupffer cell immune activation, 20 available liver blocks from equal numbers of subjects with high and low MHAI scores were dually immunostained for CD68 and the activation marker HLA-DRα. Single- and double-positive cells/HPF were enumerated in the hepatic parenchyma. Median KCD in this subgroup was lower than in the larger cohort (7.25 cells/HPF, range 1.8 – 20 cells/HPF), and the median quantity of CD68+/HLA-DRα+ was 4.15 cells/HPF(range 0 – 11.2 cells/HPF). HLA-DRα staining was found almost entirely on CD68+ cells; only a median of 0.1 (range 0 – 2.3) cells/HPF were CD68−/HLA-DR+, and this staining was confined to sinusoidal endothelial cells. There was a reciprocal trend between the number of dually-stained Kupffer cells per HPF and peripheral CD4+ lymphocyte count, but this was not statistically significant. Interestingly, the percentage of total Kupffer cells that were HLA-DR+ followed the same trend.]

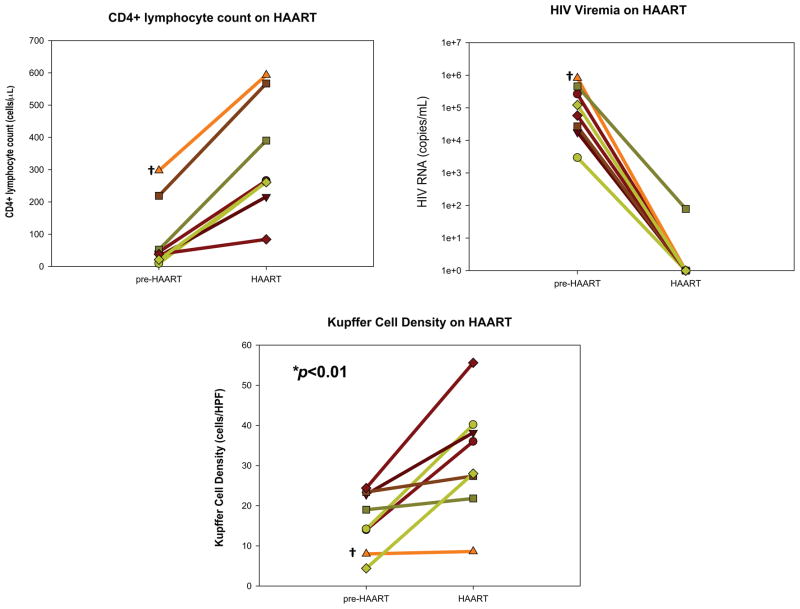

The relationship between CD4+ lymphocyte count and KCD was examined further in a select subgroup of individuals who had immunosuppression (CD4+ lymphocyte count < 350/mm3) at the time of the initial biopsy, began HAART and achieved immune restoration (≥ 2-fold increase in CD4+ lymphocyte count), then had a second biopsy with sufficient achieved tissue. In the eight evaluable subjects, biopsies were obtained at a median interval of 36.8 months (range 28.1–58.4 months). All 8 subjects had exposure to nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and protease inhibitors, and 3 subjects also had exposure to non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. The median (IQR) increase in CD4+ lymphocyte count was 246.5 (203–317) cells/mm3 and all subjects had virologic suppression on HAART to < 400 copies/mL. (Fig. 3) KCD went up in all subjects, from a median (IQR) of 16.6 (11 – 23.1) before HAART to a median (IQR) of 32 (24.6 – 39.2) during HAART exposure (p=0.007).

Fig. 3.

Eight HIV-HCV co-infected persons with at least 2 liver biopsies were selected for their initiation and response to HAART between biopsies. Biopsies were obtained at a median interval of 36.8 months apart (range 28.1 – 58.4 months). Response to HAART was defined as having a CD4+ lymphocyte count at the time of the second biopsy that was ≥ 2× the value at the time of the first biopsy (left upper panel). All subjects had virologic suppression of serum HIV RNA (right upper panel hashed reference line indicates 400 copies viral RNA/mL). KCD was measured as described on the first and second biopsies (lower panel). Symbols denote the same individuals over time and are consistent between the upper and lower panels. Because persons were preselected for increases in CD4+ lymphocyte count on HAART, a p-value was not generated for the top panel.

*comparison of mean KCD on HAART with mean KCD pre-HAART using Student’s t test.

† This individual, distinct in having the smallest increase in KCD during HAART, also had the highest pre-HAART CD4+ lymphocyte count and HIV RNA.

Discussion

Kupffer cells are the first line of defense against microbial translocation products that have been associated with liver fibrosis. In this investigation of HIV-HCV co-infected persons we have demonstrated that KCD is lowest in persons with the most AIDS-related immunosuppression compared to those with preserved CD4+ lymphocytes. In a subset of subjects who were given HAART and had immune reconstitution, KCD increased along with absolute CD4+ lymphocyte counts. These data suggest that Kupffer cell loss may contribute to liver fibrosis progression in persons with HIV-HCV co-infection and support observational studies linking HAART with slowed liver disease progression.

Immunosuppression due to HIV and other causes has been associated with HCV progression in numerous studies [3;6–8;32–35], and liver disease progression is slowed with the initiation of HAART [36;37]. There have been several explanations suggested for how HIV worsens HCV progression, and we propose that Kupffer cells may also play a role. Our data showing lower Kupffer cells in persons with the lowest CD4+ lymphocyte count, and the partial recovery of Kupffer cells with HAART and immune reconstitution suggest that the association between liver disease progression and HIV-related immunosuppression may be facilitated by Kupffer cells.

Activated Kupffer cells produce pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrogenic cytokines, such as TNFα and TGFβ that in turn activate hepatic stellate cells, the proven precursors of liver fibrosis [38]. Animal models of liver injury of different causes have revealed from macrophage-depletion experiments that liver fibrosis is Kupffer cell-dependent [16;19;39–41]. Interestingly, these experiments have shown a critical role for microbial translocation in Kupffer cell-dependent fibrosis: portal vein-derived lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and its sensing apparatus on Kupffer cells (CD14, LPS-binding protein, and TLR4) are required for the development of liver disease [16;20]. While [activated] Kupffer cells can promote fibrosis in the setting of liver injury, in the quiescent host Kupffer cells are responsible for clearing microbial translocation products [42]. [Activation of Kupffer cells, as measured by increased HLA-DR expression, has been found in HCV mono-infection [43]. In this study we noted a trend suggesting that Kupffer cells are more frequently activated in persons with the lowest CD4+ lymphocyte counts, though further work is necessary to evaluate differences between HIV-HCV co-infected and HCV mono-infected persons.] Our findings provide insights into how HIV might worsen chronic viral hepatitis.

Though it is not understood how Kupffer cell function is affected by HIV infection, earlier work has shown that HIV preferentially infects Kupffer cells over other hepatic cells [21–27]. Indeed, biopsies from HIV-infected humans and SIV-infected macaques have shown that Kupffer cells are enriched for HIV and SIV proteins, respectively [21–23;25]. Moreover, human and macaque Kupffer cells support productive HIV infection in vitro [24;26;27]. As a consequence, Kupffer cell loss may be due to the direct cytotoxic effects of HIV on the Kupffer cell, or as the result of soluble viral or host factors that induce programmed cell death. HIV infection may also alter the trafficking and migration of Kupffer cells and their precursors to target sites in the liver. Although we found no association between KCD and circulating monocyte quantities, recent data from SIV-infected macaques demonstrate that while circulating monocyte levels are unchanged from baseline in animals with AIDS, high monocyte turnover correlated tightly with AIDS progression and mortality [44].

This study also provides an explanation for the early development of periportal fibrosis in HCV infection despite clusters of HCV replication being diffusely found in the hepatic lobules. While injury and inflammation in chronic hepatitis C infection are found throughout the lobules [45], patterns of fibrosis in chronic viral hepatitis have long been identified as beginning in portal and periportal regions, supporting a role for intestinally-derived substances in enhancing fibrosis. In this study we found that Kupffer cells clustered next to portal veins where microbial translocation products first engage the liver, further strengthening an association between Kupffer cells, microbial translocation, and fibrosis and providing clues to the discordant locations of HCV replication and fibrosis in chronic HCV infection. Similar portal and periportal predominance of Kupffer cells have been found in normal and diseased rats, but the implications of an intervessel Kupffer cell gradient are poorly understood [30;31]. In our study, since the majority of study subjects had low Metavir and MHAI scores, it is unlikely that portal and periportal Kupffer cell clustering is simply a reflection of non-specific infiltrating inflammatory cells.

In this study we did not include HCV mono-infected persons, a group that will be of importance in future studies of Kupffer cell dynamics in various mono- and co-infected populations. In addition, further studies are needed to show that HIV infection of Kupffer cells is directly responsible for Kupffer cell loss. Though we did not find an association between KCD and fibrosis, our study was enriched for persons at earlier stages of liver disease, with only 9 persons who had Metavir scores ≥2 at baseline and only 10 persons who had significantly progressed fibrosis between the two biopsies. Of note, this cohort derived from a larger cohort of HIV-HCV co-infected persons who had limited amounts of fibrosis at early time points [3]. Also, because of the cross-sectional nature of our study, the impact of past Kupffer cell activity on contemporaneous liver pathology may not be captured at the instant of biopsy. As a further limitation, we did not have more than one person independently assess KCD on all slides, although ten percent of slides were scored by a second investigator with high correlation between results.

Too little is known about the relationship of KCD and their physiologic function to interpret the magnitude of differences that were observed in this study. Although the dynamic range of Kupffer cell density was limited compared to CD4+ lymphocyte counts, the LPS-clearance capacity of Kupffer cells is thought to be quite large. Indeed, after intravenous injection of LPS into rats, most was substantially cleared by the liver and nearly all of it was found in Kupffer cells [46]. Therefore, small differences in Kupffer cell density may translate to significant changes in net clearance of microbial translocation products.

Our results suggest that Kupffer cells form a dynamic cellular population that is closely tied to peripheral CD4+ lymphocyte counts and localizes to portals of microbial translocation. Hepatic macrophages are a filter of intestinally-derived products, and dysregulated macrophage survival and/or trafficking in the HIV-HCV-coinfected host may be one mechanism by which liver fibrosis rapidly progresses. Further studies into the mechanisms and consequences of HIV infection of Kupffer cells as well as the physiologic effect of Kupffer cell depletion on microbial translocation will need to be explored in in vitro and animal models.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the research subjects for the use of clinical and laboratory data, and the use of specimens. We also thank Dr. Christine Zink, Dr. Joseph Mankowski, and Chris Bartizal in the Retrovirology laboratory and Dr. Carlos Pardo and Dr. Arun Azhagiri in Neurology, both at Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions. This study is supported by R01 DA 013806, and R01 DK078686, and subjects were seen through the Clinical Research Unit at the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, M01RR-02719. The Johns Hopkins University clinical cohort database is supported by R01 DA11602, R01 AA16893, and K24 DA00432.

Abbreviations

- BD

bile duct

- CLV

centrilobular vein

- HA

hepatic artery

- HAART

highly active anti-retroviral therapy

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- IQR

interquartile range

- KCD

Kupffer cell density

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- NNRTI

non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor

- NRTI

nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors

- PI

protease inhibitor

- PV

portal vein

- SIV

simian immunodeficiency virus

- TGFβ

transforming growth factor beta

- TLR4

toll-like receptor-4

Footnotes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Weber R, Sabin CA, Friis-Moller N, et al. Liver-related deaths in persons infected with the human immunodeficiency virus: the D:A:D study. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1632–41. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.15.1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sherman KE, Rouster SD, Chung RT, Rajicic N. Hepatitis C Virus prevalence among patients infected with Human Immunodeficiency Virus: a cross-sectional analysis of the US adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:831–7. doi: 10.1086/339042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sulkowski MS, Mehta SH, Torbenson MS, et al. Rapid fibrosis progression among HIV/hepatitis C virus-co-infected adults. AIDS. 2007;21:2209–16. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f10de9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thein HH, Yi Q, Dore GJ, Krahn MD. Natural history of hepatitis C virus infection in HIV-infected individuals and the impact of HIV in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: a meta-analysis. AIDS. 2008;22:1979–91. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830e6d51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goedert JJ, Eyster ME, Lederman MM, et al. End-stage liver disease in persons with hemophilia and transfusion- associated infections. Blood. 2002;100:1584–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benhamou Y, Bochet M, Di MV, et al. Liver fibrosis progression in human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus coinfected patients. The Multivirc Group. Hepatology. 1999;30:1054–8. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin-Carbonero L, Benhamou Y, Puoti M, et al. Incidence and predictors of severe liver fibrosis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with chronic hepatitis C: a European collaborative study. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:128–33. doi: 10.1086/380130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graham CS, Baden LR, Yu E, et al. Influence of human immunodeficiency virus infection on the course of hepatitis c virus infection: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:562–9. doi: 10.1086/321909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smit-McBride Z, Mattapallil JJ, McChesney M, Ferrick D, Dandekar S. Gastrointestinal T lymphocytes retain high potential for cytokine responses but have severe CD4(+) T-cell depletion at all stages of simian immunodeficiency virus infection compared to peripheral lymphocytes. J Virol. 1998;72:6646–56. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.8.6646-6656.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Veazey RS, DeMaria M, Chalifoux LV, et al. Gastrointestinal tract as a major site of CD4+ T cell depletion and viral replication in SIV infection. Science. 1998;280:427–31. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5362.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehandru S, Poles MA, Tenner-Racz K, et al. Primary HIV-1 infection is associated with preferential depletion of CD4(+) T lymphocytes from effector sites in the gastrointestinal tract. J Exp Med. 2004;200:761–70. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guadalupe M, Reay E, Sankaran S, et al. Severe CD4(+) T-cell depletion in gut lymphoid tissue during primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection and substantial delay in restoration following highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Virol. 2003;77:11708–17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.21.11708-11717.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brenchley JM, Price DA, Schacker TW, et al. Microbial translocation is a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV infection. Nat Medicine. 2006;12:1365–71. doi: 10.1038/nm1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balagopal A, Philp FH, Astemborski J, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus-related microbial translocation and progression of hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:226–33. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paik YH, Schwabe RF, Bataller R, Russo MP, Jobin C, Brenner DA. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates inflammatory signaling by bacterial lipopolysaccharide in human hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology. 2003;37:1043–55. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seki E, De Minicis S, Osterreicher CH, et al. TLR4 enhances TGF-beta signaling and hepatic fibrosis. Nat Medicine. 2007;13:1324–32. doi: 10.1038/nm1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kono H, Rusyn I, Yin M, et al. NADPH oxidase-derived free radicals are key oxidants in alcohol-induced liver disease. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:867–72. doi: 10.1172/JCI9020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rivera CA, Adegboyega P, van Rooijen N, Tagalicud A, Allman M, Wallace M. Toll-like receptor-4 signaling and Kupffer cells play pivotal roles in the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol. 2007;47:571–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thurman RG. Mechanisms of Hepatic Toxicity II. Alcoholic liver injury involves activation of Kupffer cells by endotoxin. Am Journal Phys Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 1998;38:G605–G611. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.275.4.G605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Su GL. Lipopolysaccharides in liver injury: molecular mechanisms of Kupffer cell activation. Am Journal Phys Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;283:G256–G265. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00550.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Housset C, Boucher O, Girard PM, et al. Immunohistochemical evidence for human immunodeficiency virus-1 infection of liver Kupffer cells. Hum Pathol. 1990;21:404–8. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(90)90202-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cao YZ, Dieterich D, Thomas PA, Huang YX, Mirabile M, Ho DD. Identification and quantitation of HIV-1 in the liver of patients with AIDS. AIDS. 1992;6:65–70. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199201000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hufert FT, Schmitz J, Schreiber M, Schmitz H, Racz P, von Laer DD. Human Kupffer cells infected with HIV-1 in vivo. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1993;6:772–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Persidsky Y, Steffan AM, Gendrault JL, et al. Permissiveness of Kupffer cells for simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) and morphological changes in the liver of rhesus monkeys at different periods of SIV infection. Hepatology. 1995;21:1215–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Persidsky Y, Berger S, Gendrault JL, et al. Signs of Kupffer cell involvement in productive simian immunodeficiency virus infection in monkey liver. Res Virol. 1994;145:229–37. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2516(07)80027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmitt MP, Gendrault JL, Schweitzer C, et al. Permissivity of primary cultures of human Kupffer cells for HIV-1. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1990;6:987–91. doi: 10.1089/aid.1990.6.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmitt MP, Steffan AM, Gendrault JL, et al. Multiplication of human immunodeficiency virus in primary cultures of human Kupffer cells--possible role of liver macrophage infection in the physiopathology of AIDS. Res Virol. 1990;141:143–52. doi: 10.1016/0923-2516(90)90016-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moore RD. Understanding the clinical and economic outcomes of HIV therapy: the Johns Hopkins HIV clinical practice cohort. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1998;17 (Suppl 1):S38–S41. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199801001-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilson LE, Torbenson M, Astemborski J, et al. Progression of liver fibrosis among injection drug users with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2006;43:788–95. doi: 10.1002/hep.21091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sleyster EC, Knook DL. Relation between localization and function of rat liver Kupffer cells. Lab Invest. 1982;47:484–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bouwens L, De Bleser P, Vanderkerken K, Geerts B, Wisse E. Liver cell heterogeneity: functions of non-parenchymal cells. Enzyme. 1992;46:155–68. doi: 10.1159/000468782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gane EJ, Portmann BC, Naoumov NV, et al. Long-term outcome of hepatitis C infection after liver transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:815–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603283341302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gane EJ, Naoumov NV, Qian KP, et al. A longitudinal analysis of hepatitis C virus replication following liver transplantation. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:167–77. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8536853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prieto M, Berenguer M, Rayon JM, et al. High incidence of allograft cirrhosis in hepatitis C virus genotype 1b infection following transplantation: relationship with rejection episodes. Hepatology. 1999;29:250–6. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berenguer M, Prieto M, Rayon JM, et al. Natural history of clinically compensated hepatitis C virus-related graft cirrhosis after liver transplantation. Hepatology. 2000;32:852–8. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.17924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thein HH, Yi Q, Dore GJ, Krahn MD. Natural history of hepatitis C virus infection in HIV-infected individuals and the impact of HIV in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: a meta-analysis. AIDS. 2008;22:1979–91. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830e6d51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brau N, Salvatore M, Rios-Bedoya CF, et al. Slower fibrosis progression in HIV/HCV- coinfected patients with successful HIV suppression using antiretroviral therapy. J Hepatol. 2006;44:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Friedman SL. Mechanisms of hepatic fibrogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1655–69. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Enomoto N, Yamashina S, Kono H, et al. Development of a new, simple rat model of early alcohol-induced liver injury based on sensitization of Kupffer cells. Hepatology. 1999;29:1680–9. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bhagwandeen BS, Apte M, Manwarring L, Dickeson J. Endotoxin Induced Hepatic- Necrosis in Rats on An Alcohol Diet. J Pathol. 1987;152:47–53. doi: 10.1002/path.1711520107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adachi Y, Bradford BU, Gao WS, Bojes HK, Thurman RG. Inactivation of Kupffer Cells Prevents Early Alcohol-Induced Liver-Injury. Hepatology. 1994;20:453–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kirn A, Bingen A, Steffan AM, Wild MT, Keller F, Cinqualbre J. Endocytic capacities of Kupffer cells isolated from the human adult liver. Hepatology. 1982;2:216–22. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840020205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burgio VL, Ballardini G, Artini M, Caratozzolo M, Bianchi FB, Levrero M. Expression of co-stimulatory molecules by Kupffer cells in chronic hepatitis of hepatitis C virus etiology. Hepatology. 1998;27:1600–6. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hasegawa A, Liu H, Ling B, et al. The level of monocyte turnover predicts disease progression in the macaque model of AIDS. Blood (in press) 2009 doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-204263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pal S, Shuhart MC, Thomassen L, et al. Intrahepatic hepatitis C virus replication correlates with chronic hepatitis C disease severity in vivo. J Virol. 2006;80:2280–90. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.5.2280-2290.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Praaningvandalen DP, Brouwer A, Knook DL. Clearance Capacity of Rat-Liver Kupffer, Endothelial, and Parenchymal-Cells. Gastroenterology. 1981;81:1036–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]