Abstract

Background:

Using the Internet to replicate client/counselor interactions provides a tremendous opportunity to disseminate interventions at relatively low cost per participant. However, there are substantial challenges with this approach. The Weight Loss Maintenance Trial (WLM) compared two long-term weight-maintenance interventions: (1) a personal contact arm and (2) an Internet arm, to a third self-directed control arm. The Internet arm focused on use of an interactive website for support of long-term weight maintenance. This paper describes a highly interactive self-assessment tool developed for use in the WLM trial Internet intervention arm.

Methods:

The Tailored Self-Assessment (TSA) website tool was an interactive resource for those WLM participants assigned to the Internet arm to review their personal weight-management progress and make choices about future weight-management actions. The TSA was highly tailored and ended with a suggested list of personalized action plans. While the participant could complete the TSA at any time, criteria-based reminder messages prompted participation.

Results:

The TSA was one of 27 interactive tools on the WLM website. Over the course of the 28 months, the TSA was completed 800 times by the 348 randomized participants. Fifty-three percent of the participants (185/348) used the TSA at least once (range: 0, 110) and 72% of the 185 participants who did complete the TSA at least once, completed it more than once.

Conclusion:

The Internet has great potential to impact health behavior by attempting to replicate personal counseling. We learned that while development is complex and appears costly, tailored strategies based on client feedback are likely worthwhile and should be formally tested.

Keywords: Weight management, Internet, Behavioral intervention, Obesity, Self-assessment.

INTRODUCTION

Overweight and obesity are a huge public health problem -nearly two-thirds of US adults are overweight or obese [1]. Obesity/overweight is the second leading cause of preventable death, primarily through effects on cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors (hypertension, dyslipidemia, and Type 2 Diabetes) [2]. Behavioral interventions are standard treatment for encouraging healthy weight loss [3,4]. Use of novel, behavioral treatment approaches for weight loss have emerged in the past decade [5-7]. Given that a majority of American adults (74%) now use the Internet [8] increases in Internet-based treatments for weight loss have emerged and show some promise [9-11]. The vast scope of the overweight/obesity epidemic further demonstrates a critical need for scalable automated intervention strategies, delivered through Internet websites.

The process of successful behavior change requires self-knowledge, planning, information gathering, and modification of plans in light of new information [12]. Even in ideal circumstances with a motivated client and a skilled counselor, a typical client/counselor interaction is complex, dynamic, iterative, and non-prescriptive. Using the Internet to replicate such client/counselor interactions presents substantial challenges but also provides opportunity for widespread health benefit at relatively low cost per person. The focus of this paper is to describe a highly interactive self-assessment tool developed for use in the Weight Loss Maintenance (WLM) trial Internet intervention arm. The tool allowed participants in the WLM trial to independently assess their own progress and make future action plans based on individualized and tailored feedback.

METHODS

Design of the Weight Loss Maintenance Trial

The WLM trial was a multi-center, randomized clinical trial testing the long-term efficacy of different strategies for maintaining weight loss. The detailed review of the WLM study design is described elsewhere [13]. WLM consisted of two phases. In Phase I, participants engaged in a 6-month behavior-change weight-loss program focused on reducing caloric intake and increasing moderate intensity physical activity. Those participants who lost 4 kg or more were eligible for Phase II in which individuals were randomized into one of three groups: 1) a self-directed condition, 2) a personal contact condition, where health counselors contacted participants monthly (telephone 9 times/year and face-to-face 3 times/year), and 3) an Internet-based maintenance intervention using a website specifically designed to help participants maintain weight loss. Those assigned to the Internet-based intervention only received counseling through the website; they did not receive counseling from a person. The design process of the Internet intervention is fully described elsewhere [14] and the overall trial results have been published [15].

Participants recruited for WLM had a body mass index (BMI = weight in kg/height in cm2) of 25-45 and were taking medication for either hypertension or hyperlipidemia. To be eligible, volunteers were required to demonstrate Internet and email access by responding to an email and logging onto a screening website. Of the 1032 randomized participants, 348 were assigned into the Internet weight-loss maintenance arm. Table 1 lists demographics of the Internet participants. The group was diverse in terms of race and gender and over 60% had at least a college degree.

Table 1.

Internet Participant Demographics (N=348)

| Male | 37% |

| African American | 38% |

| Age,years, mean (sd) | 55.7 (8.5) |

| College or post college degree | 62% |

| Annual income ≥$60,000/yeara | 61% |

Seven missing values.

Internet Intervention Features

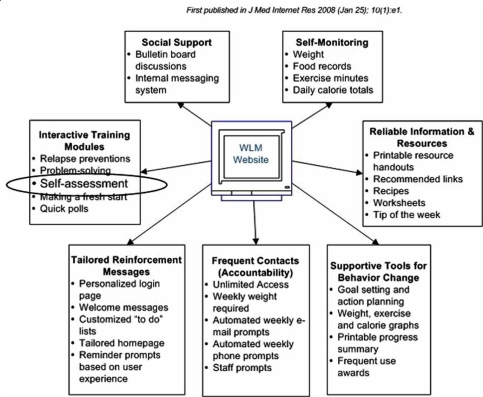

Participants assigned to this arm of the study were asked to use the website at least weekly to record their weight, physical activity, and other weight-loss efforts. The website was designed to provide a number of important intervention elements including: social support, self-monitoring, reliable information, supportive tools for change, accountability, tailored reinforcement messages and interactive modules (Fig. 1). Many of the website features attempted to replicate the interaction a client might have during a one-on-one counseling session. The tailored self-assessment (TSA) was one of the most complex modules developed for the WLM Internet website and is the focus of this paper.

Fig. (1).

Key interactive website features: first published in J Med Internet Res 2008 (Jan 25):10(1)e1 by same author.

TSA Tool

The goal of the TSA was to provide a method for participants to review their personal weight-management progress and make choices about future weight-management actions. The TSA was available for participants to complete at any time. Prompts to complete the TSA were emailed to participants who had not completed the TSA and had met specific trigger criteria indicative of weight regain (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Trigger Criteria Used for Sending TSA Reminder Messages

| Current weight compared to start of Internet Intervention: | Reminder message sent: |

|---|---|

| No more than 5 pounds above | Every 3 months |

| 5 pounds or more | Every 30 days |

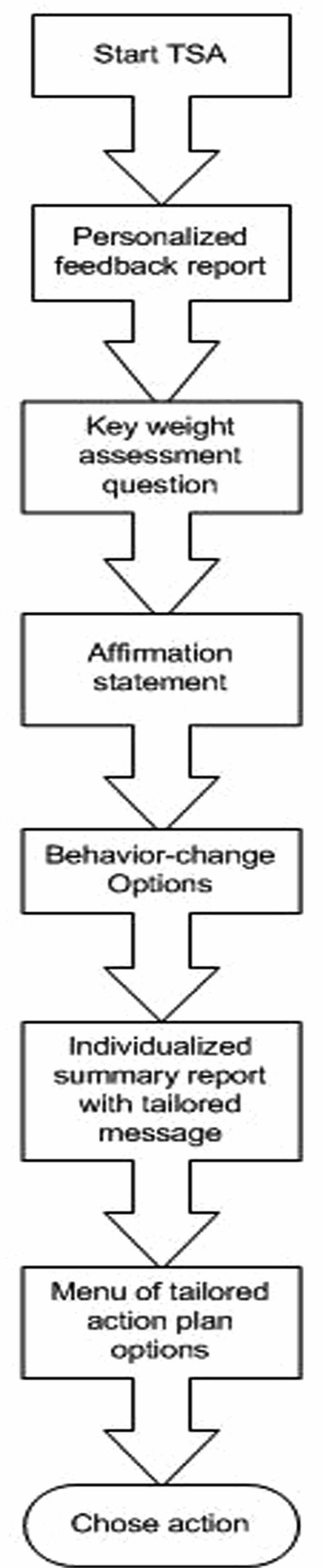

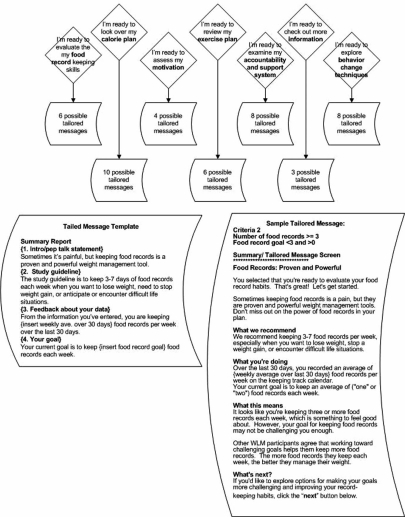

Similar to what might happen during a one-on-one counseling session, the TSA guided the participant toward optimal behavior change actions, yet ultimately facilitated choice about the direction of the session. The session took only a few minutes to complete. Using motivational interviewing techniques, the TSA was based on the FRAMES model for effective brief interventions [16]. The acronym FRAMES stands for feedback, rolling with resistance, advice about change, menu of options for change, empathy and supporting self-efficacy. A high-level overview of the flow of events in the TSA is shown in Fig. (2) and explained below. Each step in the process was individualized and tailored according to the participant’s selected area of focus and history of activity on the website.

Fig. (2).

High-level overview of the TSA flow.

Start TSA

The initial button for beginning the TSA was located on the homepage of the Internet intervention website. While participants could complete the self-assessment anytime, use was prompted when the participant saw the message, “Do Self-Assessment Now,” or “Self-Assessment done, do again?” as options on their homepage, depending on how long it had been since they last completed a TSA and their current weight status (Table 2).

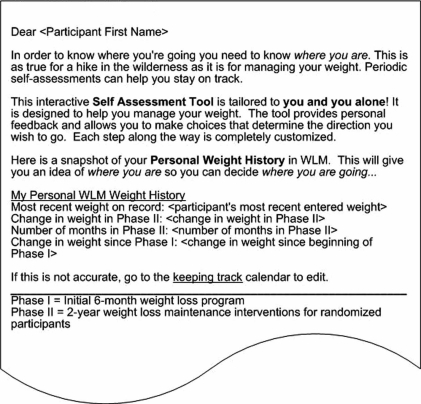

Personalized Feedback Report

When starting the TSA, the first screen participants viewed was a personalized feedback report showing their weight over the course of the study. The purpose of the report was to provide an individualized, real-time information progress report. Behavior theory suggests that to make changes, a participant must engage in a self-assessment about current progress. Fig. (3) contains a sample feedback report. If the participant chose to continue with the self-assessment, the next step was for the participant to consider and select an answer to a key weight assessment question (explained next).

Fig. (3).

Feedback report.

Key Weight Assessment Question

“Only you can evaluate your progress toward your weight goals. How would you describe your weight-management efforts of the past 30 days? Click on the box that most closely describes you.” This question allowed participants to observe their current status and make a choice about how to continue. The answer choices ranged from, “doing great,” to “really struggling,” and depending on the participant’s selection, a tailored affirmation message as well as a tailored pathway toward an action plan was shown. For our internal data systems, we considered the TSA complete when the key weight assessment question was answered.

Affirmation Statement

As with any website application, at anytime during the TSA the participant could opt to quit. Counseling techniques, like affirmation statements to build self-efficacy, are interwoven into the TSA to encourage the participant to press on and keep doing the hard work of making changes. Affirmation statements differed according to how the participant answered the weight assessment question. Table 3 shows the weight assessment question, potential answers to be selected by the participant, and the corresponding affirmation statement. This example of tailoring the affirmation again follows a motivational interviewing style by reflecting back to the participant what they have already indicated and allowing the participant to confirm their choice. The affirmation statement specifically attempts to replicate a counselor who utilizes reflective listening techniques.

Table 3.

Weight Assessment and Affirmation

|

Weight Assessment Question: Only YOU can evaluate your progress toward your weight goals. How would you describe your weight management efforts over the past 30 days? | |

|---|---|

| Answer | Affirmation |

| I’m doing great, I’m right where I want to be. | Wow, that must feel great. |

| All things considered, I’m doing fine. I’m content with where I’m at. | Super, you’re feeling good about your progress. |

| I’m not completely satisfied with my progress. I’ve lost some motivation and I could be doing better. | You’re not doing as well as you’d like. What are you ready to consider? |

| I’m very disappointed with my progress. I’m experiencing some slips and setbacks. I sense a full-blown relapse right around the corner. | You’re disappointed with your progress. What are you ready to consider? |

| I’m not making any progress. I’m having some serious struggles with my weight. | You’re struggling and that’s frustrating to you. What are you ready to consider? |

Behavior-Change Options

If the participant responded that she/he is doing well by selecting either the first or second answer, an encouragement message and an immediate action plan was displayed. In this scenario, the participant has completed the TSA and can select the suggested action plan. For those who are doing well, the encouragement message and suggested action plan reads:

“Take just a moment right now to reflect about what has made you successful. What is working for you? Your experience will no doubt be very helpful to other WLM participants. We encourage you to consider telling your success story on the participant bulletin board”.

Encouraging participants to tell their story was facilitated by the words “success story” being directly linked to the bulletin board area on the website. The action was easily implemented by the participant by clicking on the link and posting a message about what was working. Such an action is appropriate for a participant who feels she/he is doing well; it reinforces success and provides encouragement to other participants.

If the participant selected an answer that reflected less positive progress, a list of possible behavior-change options became available. In a face-to-face counseling session, a “live” counselor would likely encourage a participant who was not satisfied with his or her current progress to pare down the options, focus on one area and consider making small changes to build success. The behavior-change options used for the TSA were based on the behavior-change guidelines that served as a foundation for the entire intervention (Table 4). The topics included food records, calories, motivation, exercise plan, accountability and support, information, and behavior change techniques.

Table 4.

Behavioral Guidelines and Recommendations

| Guidelines | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| 1. Weigh yourself | Weigh yourself weekly and keep records of your weight. |

| 2. Keep calories in moderation |

To maintain current weight: Women: Consume approximately 2000 calories each day to maintain weight. Men: Consume approximately 2500 calories each day to maintain weight. For continued weight loss: Women: Consume approximately 1500-1800 calories each day to lose weight. Men: Consume approximately 2000-2300 calories each day to lose weight. |

| 3. Exercise regularly | Gradually increase your exercise duration beyond 180 minutes of moderate-intensity activity per week to achieve 225 minutes per week. (35-40 minutes, 6 days per week). |

| 4. Keep records when you need morecontrol | Keep 3-7 food records per week when you:

|

| 5. Be an active study participant | Interact at least weekly with the website and attend clinic visits. |

Individualized Summary Report with Tailored Message

A focused and tailored message was generated based on the behavior-change option selected by the participant. The tailoring involved complex, behind-the-scenes decision trees based on the current progress of the participant for the selected option compared to the study’s behavioral guideline. For instance, if a participant chose food records, a tailored message that considered the participant’s record-keeping entry history, the study guideline for record-keeping, and the participant’s self-entered goals for record keeping appeared. Each of the seven behavior-change options had between 4 and 10 tailored message possibilities. In total, there were 46 message templates, each individually tailored to the participant’s progress and based on one or more of 28 different website use variables computed behind the scenes. The behavior-change options, a message template, and a sample tailored message are shown in Fig. (4).

Fig. (4).

Behavior-change topics, tailored messages, template and sample message.

Menu of Tailored Action Plan Options

At this point in the TSA, the participant has reviewed his or her progress and selected a specific behavior-change focus. The final screen for each behavior-change area was a tailored menu of appropriate next-step actions. The participant could choose any or all of the options, or take what has been learned so far and determine his or her own plan. The options listed varied based on behind-the-scene criteria and the choice made by the participant in the previous step. Options ranged from selecting suggested links on the website that facilitated action in the focus area to reviewing key principles about behavior change or soliciting support on the bulletin board from participants experiencing similar barriers or setbacks. For each of the 46 tailored messages, there was a different list of action plan options. Each list contained 3 to 6 action plan options related to the topic area.

RESULTS

Use of the TSA

The TSA was one of over 27 interactive tools available on the WLM website. While the designers and content providers of the website desired to build features that would appeal to all participants, we understood that features would vary in usefulness for individual participants. Our goal was to provide enough variety and fresh content that all participants would find some tools helpful. The TSA, like all other modules on the website, was likely to be a tool that only some participants embraced as an essential self-check and other participants might not choose to use or, once used, would not find helpful. While our study was not designed to assess the preference of each website tool among participant users, it was designed to provide a variety of behaviorally-based modules that could be part of an overall plan to manage weight.

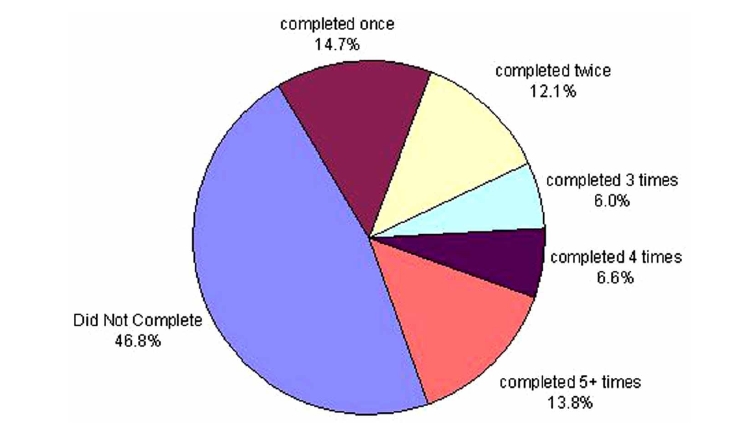

Over the 28 months of Phase II, the TSA was completed a total of 800 times. Fifty-three percent of the 348 participants randomized into the Internet arm of the study completed the TSA at least one time (range: 0, 110). Use of the TSA varied considerably. Forty-seven percent of the participants did not access the TSA at all, while 72% of the 185 participants who did complete the TSA at least once, completed it more than once. (see Fig. 5).

Fig. (5).

Proportion of participants completing the tailored self assessment (N=348).

DISCUSSION

These results may first appear somewhat discouraging especially in context to the perceived resources required to design, develop, and implement the TSA. However, the limitations discussed here and valuable lessons learned can help advance the field of designing and implementing behavioral Internet interventions for weight management.

The seemingly impossible task of replicating a personalized, one-on-one counseling session is, in fact, possible, at least to some extent. Our research did not include non-participant beta testers and focus group feedback about the TSA usefulness due to a limitation of time and resources. Even so, the complexity of counseling can be systematized and tailored (albeit in a non-personal way). Live counselors have the advantage of in-session information. They not only use objective information from and about the participant, they use clinical judgment, interpret the context of environment, read voice tone and body language, and have a real relationship with the participant. Counselors interpret all these data to direct the session discussion. Good counseling, however, diminishes the role of the counselor and in turn, gives power and choice to the client [16]. A pre-determined, but highly complex set of steps focused on specific actions plans, such as was done in creating the TSA, can act as a virtual counselor, especially if the client is ready to make changes and pre-determined criteria are developed from real counseling experience. The TSA (and other interactive modules) present non-biased reflections in response to participant input and, in that sense, lend counseling power to the participant. This aspect of Internet counseling is fertile ground for learning and enriching the field, and for discovering how to use the Internet to potentially reach larger, less accessible populations with effective interactions.

Tailoring is complex and expensive. Programming steps on a website that sequentially lead a user down a specific pathway of choices is relatively straightforward compared to tailoring that interaction to the individual. Tailoring the TSA involved complex decision trees using past progress, personal goals, and study guidelines to create individualized responses. Complicated “if” and “then” programming was necessary to execute this module. The overall cost analysis for the development and implementation of the WLM Internet intervention is published [17]. In short, the Internet intervention cost $617 per participant to implement and 90% of that cost was labor. A limitation of this research is that it did not include a formal cost analysis of the development of just one website module such as the TSA; however we estimate that at least one full-time equivalent (FTE) over six months (divided between investigator, programmer, product manager and content expert) was used to develop this module alone. Therefore, for small populations, the necessary resources for internet tailoring may well be better used in face-to-face counseling sessions. A cost-benefit is likely to only occur when the target population is immense in size (as in large health care organizations). Finally, given that a larger proportion of those who completed the TSA completed it again (134/185), it may have been beneficial if we had designed an even stronger prompt (perhaps a personal contact) to encourage participants to complete the TSA at least once.

CONCLUSION

The Internet can reach those who will not see a counselor, or where no counselor is available (rural and underserved populations) and has potential to positively impact health behavior. Internet counseling is worth considering as a viable and developing behavior-change tool. We suggest that future studies be designed to specifically test how use of major interactive features of behavioral websites impact health outcome.

TRIAL REGISTRATION

Clinicaltrials.gov NCT00054925.

REFERENCES

- 1.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults 1999-2008. JAMA. 2010;303:235–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flegal KM, Graubard BI, Williamson DF, Gail MH. Excess deaths associated with underweight, overweight, and obesity. JAMA. 2005;293:1861–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.15.1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wadden TA, Crerand CE, Brock J. Behavioral treatment of obesity. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2005;28:151–70. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2004.09.008. ix. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NHLBI. NHLBI expert panel on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: The Evidence Report. Obes Res. 1998;6:51S–209S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krukowski RA, Harvey-Berino J, Ashikaga T, Thomas CS, Micco N. Internet-based weight control: the relationship between web features and weight loss. Telemed J E Health. 2008;14:775–82. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2007.0132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tate DF, Jackvony EH, Wing RR. A randomized trial comparing human e-mail counseling, computer-automated tailored counseling, and no counseling in an Internet weight loss program. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1620–5. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.15.1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tate DF, Wing RR, Winett RA. Using Internet technology to deliver a behavioral weight loss program. JAMA. 2001;285:1172–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.9.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rainie L. Internet, broadband and cell phone statistics. Pew Internet & American Life Project. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krukowski RA, West DS, Harvey-Berino J. Recent advances in internet-delivered, evidence-based weight control programs for adults. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2009;3:184–9. doi: 10.1177/193229680900300122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Webber KH, Tate DF, Michael BJ. A randomized comparison of two motivationally enhanced Internet behavioral weight loss programs. Behav Res Ther. 2008;46:1090–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wing RR, Tate DF, Gorin AA, Raynor HA, Fava JL. A self-regulation program for maintenance of weight loss. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1563–1571. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watson DL, Tharp RG, editors. Self-directed behavior: Self-modification for personal adjustment. 8th. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brantley P, Appel L, Hollis J, et al. Design considerations and rationale of a multi-center trial to sustain weight loss: the weight loss maintenance trial. Clin Trials. 2008;5:546–556. doi: 10.1177/1740774508096315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stevens VJ, Funk K, Brantley PJ, et al. Design and implementation of an interactive web site to support long-term behavior change. J Med Intern Res. 2008;10:e1. doi: 10.2196/jmir.931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Svetkey LP, Stevens VJ, Brantley PJ, et al. Comparison of strategies for sustaining weight loss: The weight loss maintenance randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:1139–1148. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.10.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2nd Edition. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meenan RT, Stevens VJ, Funk K, et al. Development and Implementation cost analysis of telephone-and Internet-based interventions for the maintenance of weight loss. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2009;25(3):400–10. doi: 10.1017/S0266462309990018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]