Abstract

Objective To examine the effect of proton pump inhibitors on adverse cardiovascular events in aspirin treated patients with first time myocardial infarction.

Design Retrospective nationwide propensity score matched study based on administrative data.

Setting All hospitals in Denmark.

Participants All aspirin treated patients surviving 30 days after a first myocardial infarction from 1997 to 2006, with follow-up for one year. Patients treated with clopidogrel were excluded.

Main outcome measures The risk of the combined end point of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke associated with use of proton pump inhibitors was analysed using Kaplan-Meier analysis, Cox proportional hazard models, and propensity score matched Cox proportional hazard models.

Results 3366 of 19 925 (16.9%) aspirin treated patients experienced recurrent myocardial infarction, stroke, or cardiovascular death. The hazard ratio for the combined end point in patients receiving proton pump inhibitors based on the time dependent Cox proportional hazard model was 1.46 (1.33 to 1.61; P<0.001) and for the propensity score matched model based on 8318 patients it was 1.61 (1.45 to 1.79; P<0.001). A sensitivity analysis showed no increase in risk related to use of H2 receptor blockers (1.04, 0.79 to 1.38; P=0.78).

Conclusion In aspirin treated patients with first time myocardial infarction, treatment with proton pump inhibitors was associated with an increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events.

Introduction

The possible interactions between antithrombotic drugs and proton pump inhibitors resulting in reduced antithrombotic effect and increased cardiovascular risk for patients receiving combination therapy has received much attention. Particular attention has been given to the interaction between clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors, but an interaction between aspirin and proton pump inhibitors has also been proposed.

Aspirin inhibits platelet aggregation and remains a cornerstone in the management of atherothrombotic disease,1 2 despite the questionable net value of aspirin treatment in primary prevention.3 Owing to the gastrointestinal side effects associated with aspirin, proton pump inhibitors are widely used for the prevention of peptic ulcers in patients treated with aspirin, and guidelines advocate the use of proton pump inhibitors in a wide group of patients treated with aspirin after myocardial infarction.4 It has been suggested, however, that treatment with proton pump inhibitors may reduce the bioavailability of aspirin, resulting in reduced platelet inhibition.5 Proton pump inhibitors exert a suppressive effect on the production of gastric acid and therefore have the potential to alter the extent of drug absorption through modification of intragastric pH. The results of recent studies on whether treatment with proton pump inhibitors significantly influences aspirin induced inhibition of platelet aggregation have been conflicting.6 7

We studied a large unselected cohort of patients admitted to hospital with a first ever myocardial infarction, with particular focus on the risk of adverse cardiovascular events associated with concomitant treatment with aspirin and proton pump inhibitors.

Methods

We carried out a retrospective complete nationwide study based on information from four Danish national registers. Every resident in Denmark is provided with a permanent and unique civil registration number at birth, enabling linkage between registers at individual level. Immigrants are assigned a civil registration number when they are registered as residents. We combined data on primary admissions to hospital, pharmacy prescription claims, subsequent admissions to hospital, and deaths for 3.7 million people.

The Danish national patient registry registers all hospital admissions in Denmark with one primary diagnosis and, if appropriate, one or more secondary diagnoses, according to the International Classification of Diseases. The national prescription registry keeps records of every prescription dispensed from pharmacies in Denmark, with each drug being classified according to the international Anatomical Therapeutical Chemical system. The Danish civil registry and the national causes of death registry keep information on vital status and causes of death.

Patients

We identified all consecutive patients, aged 30 years or more, admitted to hospital with a first myocardial infarction (ICD-10 codes I21-I22) as a primary or secondary diagnosis between 1997 and 2006. We excluded patients treated with clopidogrel owing to the recent controversy related to the effects of its use with proton pump inhibitors. The study therefore included patients treated only with aspirin. Patients were identified according to claimed prescriptions within 30 days from discharge. To ensure equal time for all patients to claim prescriptions for aspirin and to minimise the risk of immortal time bias, we only included patients surviving 30 days after discharge. We excluded patients with partially missing data, and patients emigrating were censored at the time of emigration. Income group was defined by the individual average yearly gross income during a five year period before study inclusion, and patients were divided into fifths according to their income.

Drug use

Information on concomitant drug use was based on claimed prescriptions in the 90 days after discharge (180 days for statins),8 except for information on use of proton pump inhibitors, H2 receptor blockers, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, which was based on all claimed prescriptions within one year after discharge. The information included dispensing date; drug type, quantity, and dose; and days of drug supply, but did not contain data on patient reported adherence. We defined current use as the period from the date the prescription was filled to the calculated end of the drug supply period. The national prescription register has been shown to be accurate.9 The standard dose of aspirin after myocardial infarction in Denmark is 75 mg once daily.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the combined end point of death from cardiovascular causes and readmission to hospital for myocardial infarction or stroke. Secondary outcomes were all cause death, cardiovascular death, and readmission to hospital for myocardial infarction or stroke. Follow-up was one year after discharge. The diagnoses of acute myocardial infarction and stroke have been validated in the national patient registry.10 11

Comorbidity

We defined comorbidity from diagnoses at discharge after the index myocardial infarction as specified in the Ontario acute myocardial infarction mortality prediction rule.12 The comorbidity index was further optimised by adding diagnoses from the year before the event, as previously described.13

To define high risk subgroups of patients, we used the concomitant use of loop diuretics or drugs for diabetes as a proxy for heart failure and diabetes, respectively.

Statistical analyses

Baseline characteristics are presented as numbers (percentages) for categorical variables and as means (standard deviations) for continuous variables. We used Kaplan-Meier estimates to generate time to event curves for the primary end point.

To consolidate the strength of our findings we used two statistical methods to estimate the risk associated with treatment using proton pump inhibitors. Firstly, we constructed Cox proportional hazards models to derive hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals. We adjusted the models for age, sex, year of inclusion, percutaneous coronary intervention, income group, concomitant medical treatment, and comorbidity. Use of proton pump inhibitors was included as a time dependent covariate. Secondly, we carried out a propensity score matched Cox proportional hazard analysis. We quantified a propensity score for the likelihood of receiving proton pump inhibitors within the first year from discharge by multivariate logistic regression analysis conditional on baseline covariates (see table 1). Using the Greedy matching macro (http://mayoresearch.mayo.edu/mayo/research/biostat/upload/gmatch.sas) we matched each case to one control on the basis of the propensity score. Use of proton pump inhibitors during follow-up was again included as a time dependent covariate.

To further assess the robustness of our results we did a series of additional analyses, including an analysis using the method by Schneeweiss that evaluates how large the effect of an unmeasured confounder or combination of confounders would need to be account for the results,14 together with analysis of high risk patient subgroups, analysis dependent on subtype of proton pump inhibitor, a dose dependent analysis, and an analysis of the effect of concomitant use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Statistical calculations were carried out with SAS version 9.2.

Results

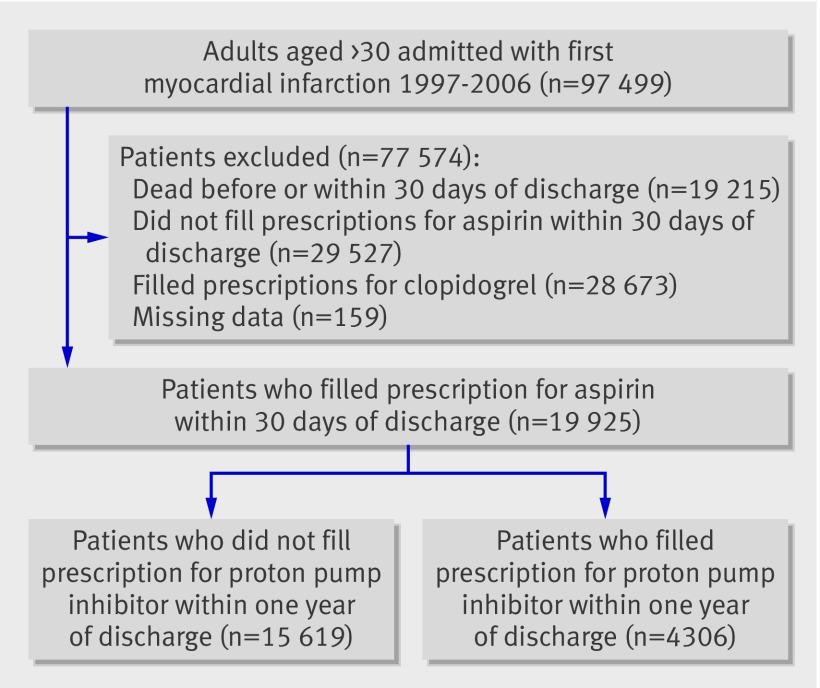

A total of 97 499 adults over the age of 30 were admitted with a first myocardial infarction during 1997 to 2006 (fig 1). Of these, 48 047 were excluded: 19 215 patients died before or within 30 days of discharge, 28 673 were treated with clopidogrel, and 159 had partially missing data. Of the remaining 49 452 patients, 19 925 filled a prescription for aspirin within 30 days and comprised the study cohort. Of these, 4306 (21.6%) claimed at least one prescription for proton pump inhibitors and 661 (3.3%) filled at least one prescription for H2 receptor blockers within one year of discharge. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the study population. Patients treated with proton pump inhibitors were older, more often female, received more concomitant medical treatment, and had more comorbidity than patients not treated with proton pump inhibitors. Baseline characteristics were balanced in the propensity matched populations.

Fig 1 Flow chart of patients through study

Table 1 Baseline characteristics and propensity score matched baseline characteristics at inclusion. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | Baseline | Propensity score matched baseline | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients not treated with PPIs (n=15 619) | Patients treated with PPIs (n=4306) | P value for difference | Patients not treated with PPIs (n=4159) | Patients treated with PPIs (n=4159) | P value for difference | ||

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 69.9 (13.0) | 72.7 (12.3) | <0.001 | 72.7 (12.6) | 72.5 (12.1) | 0.48 | |

| Men | 9638 (61.7) | 2318 (53.8) | <0.001 | 2212 (53.2) | 2242 (53.9) | 0.51 | |

| Income group: | <0.001 | 0.71 | |||||

| 0 | 3331 (21.3) | 888 (20.6) | 893 (21.5) | 857 (20.6) | |||

| 1 | 3196 (20.5) | 1056 (24.5) | 999 (24.0) | 1002 (24.1) | |||

| 2 | 3007 (19.3) | 980 (22.8) | 936 (22.5) | 949 (22.8) | |||

| 3 | 3171 (20.3) | 8123 (18.9) | 752 (18.1) | 791 (19.0) | |||

| 3 | 2914 (18.7) | 570 (13.2) | 579 (13.9) | 560 (13.5) | |||

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 879 (5.6) | 253 (5.9) | 0.53 | 235 (5.7) | 249 (6.0) | 0.51 | |

| Medical condition: | |||||||

| Shock | 116 (0.7) | 74 (1.7) | <0.001 | 53 (1.3) | 61(1.5) | 0.45 | |

| Diabetes with complications | 721(4.6) | 244 (5.7) | 0.005 | 192 (4.6) | 231(5.6) | 0.05 | |

| Peptic ulcer | 68 (0.4) | 186 (4.3) | <0.001 | 68 (1.6) | 72 (1.7) | 0.73 | |

| Pulmonary oedema | 193 (1.2) | 62 (1.4) | 0.29 | 59 (1.4) | 59 (1.4) | 1.00 | |

| Cerebral vascular disease | 647 (4.1) | 276 (6.4) | <0.001 | 240 (5.8) | 255 (6.1) | 0.49 | |

| Cancer | 61 (0.4) | 27 (0.6) | 0.04 | 19 (0.5) | 25 (0.6) | 0.36 | |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | 1646 (10.5) | 547 (12.7) | <0.001 | 492 (11.8) | 520 (12.5) | 0.35 | |

| Acute renal failure | 75 (0.5) | 73 (1.7) | <0.001 | 49 (1.2) | 54 (1.3) | 0.62 | |

| Chronic renal failure | 103 (0.7) | 116 (2.7) | <0.001 | 86 (2.1) | 91 (2.2) | 0.70 | |

| Prescribed drugs: | |||||||

| Loop diuretics | 7015 (44.9) | 2467 (57.3) | <0.001 | 2346 (56.4) | 2365 (56.9) | 0.67 | |

| Spironolactone | 1374 (8.8) | 577 (13.4) | <0.001 | 510 (12.3) | 556 (13.4) | 0.13 | |

| Statins | 6920 (44.3) | 1960 (45.5) | 0.16 | 1953 (47.0) | 1907 (45.9) | 0.31 | |

| β blockers | 11 157 (71.4) | 2993 (69.5) | 0.01 | 2926 (70.4) | 2891 (69.5) | 0.40 | |

| ACE inhibitors | 6553 (42.0) | 1890 (43.9) | 0.02 | 1891 (45.5) | 1829 (44.0) | 0.17 | |

| Antidiabetes drugs | 1847 (11.8) | 513 (14.2) | <0.001 | 531 (12.8) | 587 (14.1) | 0.07 | |

| Vitamin K antagonist | 1169 (7.5) | 353 (8.2) | 0.12 | 318 (7.7) | 343 (8.3) | 0.31 | |

PPIs=proton pump inhibitors; ACE=angiotensin converting enzyme.

Outcomes

During the year of follow-up, 3365 (16.9%) cardiovascular deaths and readmissions to hospital for myocardial infarction or stroke and 2293 (11.5%) all cause deaths occurred. Table 2 shows the distribution of events.

Table 2.

Association between treatment with proton pump inhibitors and risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Values are hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) unless stated otherwise

| Outcome | Events during follow-up | Time to dependent Cox proportional hazards regression | P value | Propensity score matched Cox proportional hazards regression analysis | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients not treated with PPIs | Patients treated with PPIs | |||||

| Cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke | 2378 (15.2) | 987 (22.9) | 1.46 (1.33 to 1.61) | <0.001 | 1.61 (1.45 to 1.79) | <0.001 |

| All cause death | 1607 (10.3) | 686 (15.9) | 1.78 (1.60 to 1.98) | <0.001 | 2.38 (2.12 to 2.67) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular death | 1328 (8.5) | 540 (12.5) | 1.71 (1.51 to 1.92) | <0.001 | 2.19 (1.92 to 2.49) | <0.001 |

| Myocardial infarction | 1110 (7.1) | 497 (11.5) | 1.39 (1.20 to 1.62) | <0.001 | 1.33 (1.13 to 1.56) | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 1207 (7.7) | 338 (7.9) | 1.23 (1.03 to 1.47) | 0.03 | 1.20 (0.99 to 1.46) | 0.06 |

PPIs=proton pump inhibitors.

Use of proton pump inhibitors was included as time to dependent covariate.

Time dependent analyses

The multivariate time dependent Cox proportional hazards regression analysis yielded a hazard ratio of 1.46 (95% confidence interval 1.33 to 1.61; P<0.001) for the composite end point in patients receiving proton pump inhibitors compared with those not treated with proton pump inhibitors. The results for secondary outcomes were similar (table 2).

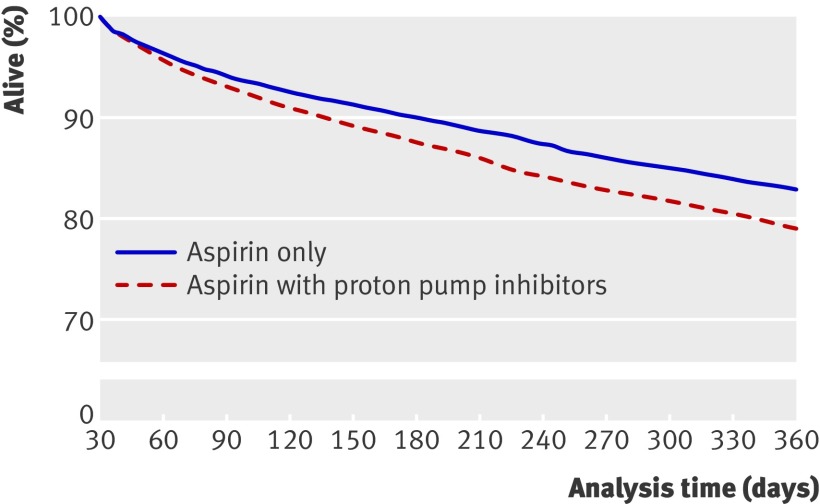

Using propensity score, 4159 patients treated with aspirin and proton pump inhibitors were matched with an equal number of patients not treated with proton pump inhibitors. Table 2 shows the baseline characteristics of the propensity score matched populations and P values for differences between the groups and table 3 gives details of the matching (also see web extra table 1 and fig 1). Treatment compared with no treatment with proton pump inhibitors yielded a hazard ratio for cardiovascular death and readmission to hospital for myocardial infarction or stroke of 1.61 (1.45 to 1.79; P<0.001). The C statistic was 0.67, indicating good discriminative power of the models. The hazard ratio for all cause death was 2.38 (2.12 to 2.67; P<0.001). Analyses of the risk of the other secondary outcomes generated similar hazard ratios. The propensity score matched Kaplan-Meier analysis depicts the increased risk of cardiovascular death and of readmission to hospital for myocardial infarction or stroke for patients treated with or without proton pump inhibitors (fig 2).

Table 3.

Propensity score matched model results of probability of treatment with proton pump inhibitors during one year of follow-up

| Characteristics | Estimates | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.01 | 0.99 (0.95 to 1.03) | 0.56 |

| Year | 0.17 | 1.18 (1.17 to 1.20) | <0.001 |

| Male sex | −0.17 | 0.85 (0.79 to 0.91) | <0.001 |

| Income group | −0.08 | 0.92 (0.89 to 0.95) | <0.001 |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 0.22 | 1.25 (1.07 to 1.45) | 0.005 |

| Medical condition: | |||

| Shock | 0.46 | 1.59 (1.17 to 2.17) | 0.003 |

| Diabetes with complications | −0.18 | 0.83 (0.69 to 1.00) | 0.05 |

| Peptic ulcer | 2.18 | 8.86 (6.64 to 11.82) | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary oedema | −0.16 | 0.85 (0.63 to 1.15) | 0.30 |

| Cerebral vascular disease | 0.24 | 1.27 (1.09 to 1.48) | 0.003 |

| Cancer | 0.43 | 1.53 (0.94 to 2.48) | 0.08 |

| Cardiac dysrhythmias | −0.08 | 0.92 (0.82 to 1.03) | 0.14 |

| Acute renal failure | 0.61 | 1.85 (1.29 to 2.64) | <0.001 |

| Chronic renal failure | 0.94 | 2.58 (1.93 to 3.46) | <0.001 |

| Prescribed drugs: | |||

| Loop diuretics | 0.33 | 1.39 (1.28 to 1.50) | <0.001 |

| Spironolacton | 0.14 | 1.16 (1.03 to 1.29) | 0.01 |

| Statin | −0.05 | 0.95 (0.88 to 1.03) | 0.25 |

| β blocker | −0.01 | 0.99 (0.92 to 1.08) | 0.88 |

| ACE inhibitor | −0.07 | 0.93 (0.88 to 0.99) | 0.01 |

| Antidiabetes drugs | 0.10 | 1.10 (0.98 to 1.24) | 0.12 |

| Vitamin K antagonist | −0.09 | 0.91 (0.80 to 1.05) | 0.19 |

ACE=angiotensin converting enzyme.

Fig 2 Propensity score matched Kaplan-Meier analysis of risk of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke

Sensitivity analyses

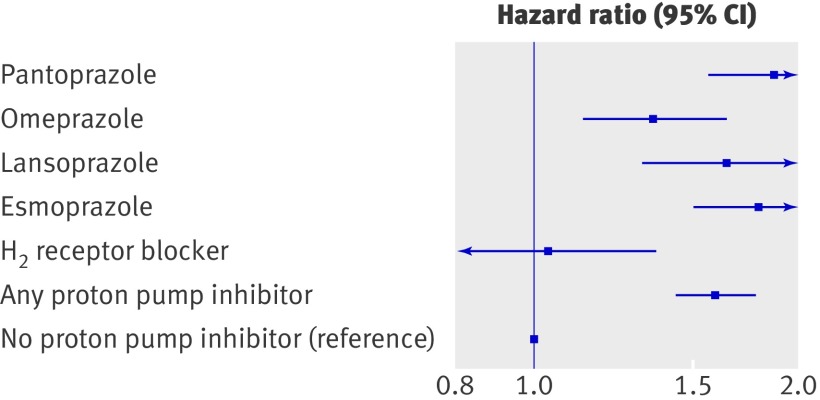

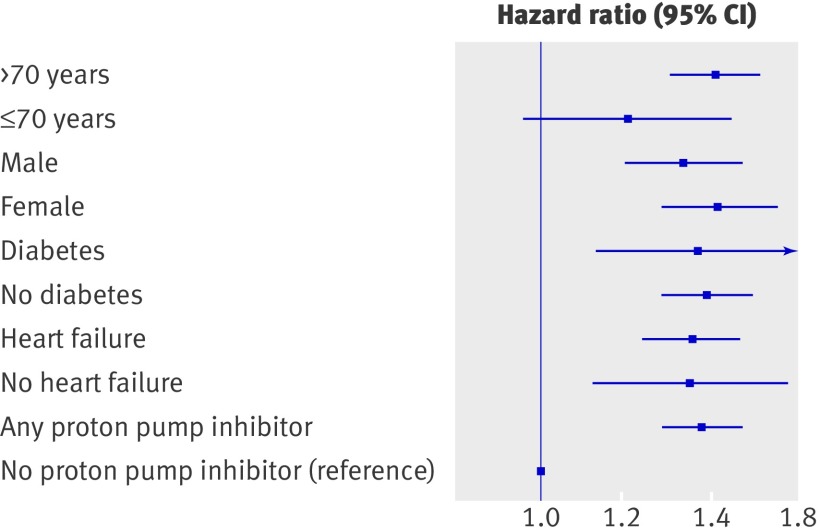

A time dependent propensity score matched Cox proportional hazards regression sensitivity analysis showed no increase in risk related to concomitant treatment with aspirin and H2 receptor blockers (hazard ratio 1.04, 95% confidence interval 0.79 to 1.38; P=0.78) (fig 3). Interaction analyses between relevant subgroups of patients identified no interaction between treatment with proton pump inhibitors and outcomes. Figure 4 shows the results of the sensitivity analyses for high risk subgroups. The data did not provide any evidence of differences in risk related to age, sex, diabetes, or heart failure.

Fig 3 Time dependent adjusted propensity score matched Cox proportional hazard analysis of risk of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke for subtypes of proton pump inhibitors and H2 receptor blockers

Fig 4 Time dependent adjusted Cox proportional hazard analysis of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke in high risk patient subgroups treated with proton pump inhibitors. Diabetes=requiring glucose lowering drugs

Of the 4306 patients claiming at least one prescription for proton pump inhibitors, 1128 (26.2%) claimed prescriptions for pantoprazole, 741 (17.2%) for lansoprazole, 1264 (29.4%) for omeprazole, 1043 (26.5%) for esmoprazole, and 30 (0.01%) for rabeprazole. Of the 15 619 patients not treated with proton pump inhibitors, 661 filled a prescription for H2 receptor blockers. Results from the time dependent propensity score matched Cox proportional hazards regression analysis (see fig 3) showed no difference in risk associated with different subtypes of proton pump inhibitors. Rabeprazole was not included in this analysis as the cohort was too small to generate reliable results. In the analysis testing for additional effect modification related to concomitant use of ibuprofen or any non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, no interaction was found (P for interaction 0.93 and 0.92, respectively).

Using time dependent propensity score matching conditional on baseline covariates predicting treatment with proton pump inhibitors, the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding was analysed in patients treated with aspirin and proton pump inhibitors; compared with patients not receiving proton pump inhibitors the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding was not reduced (hazard ratio 1.02, 0.72 to 1.43; P=0.91).

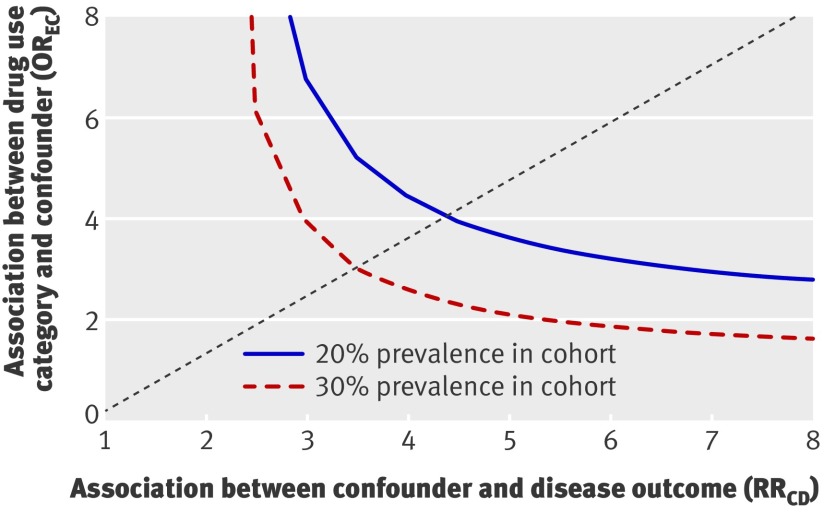

When testing how large the effect of a potential unmeasured confounder or combination of confounders would need to be to fully explain the increased risk observed in patients treated with proton pump inhibitors and aspirin, if an unmeasured confounder was present in 20% of the population receiving proton pump inhibitors, the confounder would have to increase the risk by a factor of 4 to increase the hazard ratio from 1.00 to 1.61 (fig 5). Further sensitivity analysis did not provide evidence of any difference between high (150 mg) and low doses (75 to 100 mg) of aspirin or between high and low doses of proton pump inhibitors (P=0.92 and 0.49, respectively, for difference in risk between high and low doses).

Fig 5 Requested size of unmeasured confounder to fully explain increase in risk from 1.00 to 1.61

Discussion

In aspirin treated patients with first time myocardial infarction there was an increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events associated with treatment using proton pump inhibitors. This study was the first to examine the clinical effects of a possible interaction between aspirin and proton pump inhibitors by investigating the risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes in a nationwide unselected population of patients with first time myocardial infarction.

Possible pathophysiology of interaction between aspirin and proton pump inhibitors

Proton pump inhibitors protect the gastric mucosal barrier by suppressing gastric acid production.15 Under physiological acidic conditions, aspirin is absorbed in its lipid state by passive diffusion across the gastric mucosal membrane according to the pH partition hypothesis.16 Proton pump inhibitors exert their antacid effect by inhibiting the H+/K+ exchanging ATP-ase of the gastric parietal cells, thus raising intragastric pH.17 In fact the pH potentially rises above the pKa (3.5) of acetylsalicylic acid (that is, the negative logarithm of the acidic dissociation constant of a substance), thus reducing the lipophilicity of aspirin and hence the absorption of the drug.5 According to previous studies, such chemical changes might compromise the bioavailability and therapeutic efficacy of aspirin.18 19 20 As all proton pump inhibitors affect gastric pH to roughly the same extent, the interaction between aspirin and these drugs is likely to represent a class effect of proton pump inhibitors.21 Along this line, a recent study found that patients treated with proton pump inhibitors had a reduced platelet response to aspirin in terms of increased residual platelet aggregation and platelet activation compared with patients not taking proton pump inhibitors.7

Is there a clinical effect of the observed ex vivo effect?

Currently, the debate about the possibility of a reduced antiplatelet effect of clopidogrel in patients receiving proton pump inhibitors and whether such possible interaction has a significant clinical effect is intense.22 23 24 25 26 27 28 This uncertainty also raises the question of whether the observed reduced ex vivo antiplatelet effect of aspirin during treatment with proton pump inhibitors has any clinical effect on cardiovascular risk. Our study explored the clinical effect of such potential interaction between aspirin and proton pump inhibitors by investigating the risk of adverse cardiovascular events in a nationwide unselected aspirin treated population with first time myocardial infarction. We found a significant effect of treatment with proton pump inhibitors on cardiovascular outcomes for patients treated with aspirin. This effect was slightly higher in the propensity score matched analysis, mainly reflecting the differences between the two reference groups in the main analyses and the propensity score matched analyses.

Possible explanations for the observed increased risk

There are several possible explanations for the increased cardiovascular risk associated with concomitant treatment with proton pump inhibitors in aspirin treated patients. Firstly, the increased risk results from modification of intragastric pH, causing reduced bioavailability of aspirin and thereby increased residual platelet aggregation and platelet activation, as previously reported.7 Secondly, treatment with proton pump inhibitors itself increases the risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes owing to an as yet unknown physiological or biological pathway. Thirdly, the increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events related to concomitant treatment with aspirin and proton pump inhibitors is caused by unmeasured differences in baseline comorbidities. If this was the case, however, our calculations showed that if an unmeasured confounder or a combination of confounders was present in 20% of the cohort treated with proton pump inhibitors, the confounder would have to increase the risk by a factor of 4 to explain the increased risk observed in our study. Existence of such confounders or combination of confounders is unlikely, but not impossible, since we had no information on other important risk factors such as lipid levels, body mass index, or smoking. Smoking is an important confounder as it increases the risk of peptic ulcers and therefore channels a patient towards treatment with proton pump inhibitors, but smoking also increases the risk of recurrent myocardial infarction and death. Importantly, any such confounding would also affect patients receiving H2 receptor blockers, which have identical therapeutic indications as proton pump inhibitors. Notably, we did not observe an increased risk associated with treatment using H2 receptor blockers, supporting the hypothesis of the unique effects of proton pump inhibitors on the antithrombotic properties of aspirin. Finally, the possibility remains that the increased cardiovascular risk observed in patients receiving concomitant treatment with aspirin and proton pump inhibitors was caused by a combination of the other three potential explanations.

Clinical relevance for the suggested clopidogrel-proton pump inhibitor interaction

If the findings of this study are seen in the light of the recent discussion of the potential interaction between proton pump inhibitors and clopidogrel, they raise an important question: whether the putative interaction between clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors may be explained, at least in part, by an interaction between aspirin and proton pump inhibitors, as virtually all patients treated with clopidogrel also receive aspirin. Interestingly, we recently found an increased cardiovascular risk associated with proton pump inhibitors independent of clopidogrel use.26

Other analyses

Recent studies have shown an increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding in patients receiving dual antiplatelet treatment without proton pump inhibitors, emphasising the importance of evaluating the cardiovascular safety of concomitant treatment with proton pump inhibitors.29 We were not able to show a reduced risk of gastrointestinal bleeding in aspirin treated patients receiving proton pump inhibitors. In Denmark, proton pump inhibitors are not prescribed routinely for patients receiving aspirin but mainly for patients with a clear therapeutic indication, such as peptic ulcer disease. Thus the aspirin group treated with proton pump inhibitors in our study was probably confounded by indication for proton pump inhibitors and consequently had a higher risk of bleeding than patients in countries where guidelines recommend routine use of proton pump inhibitors in combination with dual antiplatelet therapy. This confounding may explain why we were not able to show any effect of treatment with proton pump inhibitors on gastrointestinal bleeding. Other studies have found that concomitant treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, especially ibuprofen, antagonises the irreversible platelet inhibition induced by aspirin.30 We found no additional effect modification related to concomitant use of ibuprofen or any non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in our study.

In addition, we did not observe any differences in risk between subtypes of proton pump inhibitors or high or low doses of proton pump inhibitors and aspirin. Sensitivity analyses did not provide evidence of differences in risk related to sex, age, or presence of heart failure or diabetes.

Strengths and limitations of the study

Important strengths of the study include the large size of our study sample and the fact that it was based on a nationwide unselected cohort of patients after myocardial infarction in a clinical setting. The Danish national patient registry includes all hospital admissions in Denmark and is therefore not affected by selection bias from, for example, selective inclusion of specific hospitals, health insurance systems, or age groups. The concordance between drug dispensing and drug use is likely to be high, since reimbursement of drug expenses is only partial and most drugs, including proton pump inhibitors, were not available over the counter in Denmark during the study period. Exceptions were aspirin and H2 receptor blockers. This explains why so few patients filled prescriptions for aspirin during the first 30 days after discharge. Because adherence to drugs has been documented to be high in Danish patients after myocardial infarction (for example, 85% adherence to statins 12 months after myocardial infarction),8 we assume that most patients who did not fill a prescription for aspirin were treated with over the counter aspirin, even though we cannot completely rule out the possibility of selection bias. Additional limitations of the study are that generalisation of these data to other racial and ethnic groups should be made with caution and that we did not have any information on the indication for treatment with proton pump inhibitors.

Conclusions

In this study of a large unselected nationwide population we found that use of proton pump inhibitors in aspirin treated patients with first time myocardial infarction was associated with an increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events. The increased risk was not observed in patients treated with H2 receptor blockers. It is unlikely, but not impossible, that the increased cardiovascular risk associated with concomitant use of aspirin and proton pump inhibitors is caused by unmeasured confounders. Focus on this area, including the implication of this study for the discussion on clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors is warranted owing to the large clinical implications of a possible interaction between proton pump inhibitors and aspirin. Randomised prospective studies as well as observational studies based on other populations are needed.

What is already known on this topic

Guidelines recommend dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel after myocardial infarction

The possible interaction between clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors is widely debated

Evidence from recent ex vivo studies suggests that proton pump inhibitors may reduce the platelet inhibitory effect of aspirin in patients with cardiovascular disease

What this study adds

In this study of a large unselected nationwide cohort of aspirin treated patients with first time myocardial infarction, use of proton pump inhibitors was associated with an increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events

Contributors: MC, ELG, PRH, CT-P, and GHG conceived and designed the study. All authors analysed and interpreted the data, critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, and provided administrative, technical, or material support. MC and GHG carried out the statistical analysis. MC drafted the manuscript. MC and CT-P obtained funding. MC, CT-P, and GHG had full access to the data and take full responsibility for its integrity.

Funding: This study was funded by the Danish Heart Foundation (10-04-R78-A2865-22586). The funding source had no influence on the study design, interpretation of results, or decision to submit the article.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare that (1) none haS company support for the submitted work; (2) the authors have no relationships with companies that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; (3) their spouses, partners, or children have no financial relationships that may be relevant to the submitted work; and (4) the authors have no non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (2007-41-1667) and data at the individual case level were made available by the national registers in anonymised form. Registry studies do not require ethical approval in Denmark.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2011;342:d2690

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Summary data for propensity score matched cases and controls

Distribution of probabilities of treatment with proton pump inhibitors in propensity score matched model

References

- 1.Antithrombotic Trialists C. Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ 2002;324:71-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith SC Jr, Allen J, Blair SN, Bonow RO, Brass LM, Fonarow GC, et al. AHA/ACC guidelines for secondary prevention for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2006 update: endorsed by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Circulation 2006;113:2363-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antithrombotic Trialists C. Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet 2009;373:1849-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhatt DL, Scheiman J, Abraham NS, Antman EM, Chan FK, Furberg CD, et al. ACCF/ACG/AHA 2008 expert consensus document on reducing the gastrointestinal risks of antiplatelet therapy and NSAID use: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. Circulation 2008;118:1894-909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giraud MN, Sanduja SK, Felder TB, Illich PA, Dial EJ, Lichtenberger LM. Effect of omeprazole on the bioavailability of unmodified and phospholipid-complexed aspirin in rats. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1997;11:899-906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adamopoulos AB, Sakizlis GN, Nasothimiou EG, Anastasopoulou I, Anastasakou E, Kotsi P, et al. Do proton pump inhibitors attenuate the effect of aspirin on platelet aggregation? A randomized crossover study. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2009;54:163-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wurtz M, Grove EL, Kristensen SD, Hvas AM. The antiplatelet effect of aspirin is reduced by proton pump inhibitors in patients with coronary artery disease. Heart;96:368-71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Gislason GH, Rasmussen JN, Abildstrom SZ, Gadsboll N, Buch P, Friberg J, et al. Long-term compliance with beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and statins after acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 2006;27:1153-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaist D, Sorensen HT, Hallas J. The Danish prescription registries. Dan Med Bull 1997;44:445-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madsen M, Davidsen M, Rasmussen S, Abildstrom SZ, Osler M. The validity of the diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction in routine statistics: a comparison of mortality and hospital discharge data with the Danish MONICA registry. J Clin Epidemiol 2003;56:124-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krarup LH, Boysen G, Janjua H, Prescott E, Truelsen T. Validity of stroke diagnoses in a national register of patients. Neuroepidemiology 2007;28:150-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tu JV, Austin PC, Walld R, Roos L, Agras J, McDonald KM. Development and validation of the Ontario acute myocardial infarction mortality prediction rules. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;37:992-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rasmussen SM, Zwisler AD, Abildstrom SZ, Madsen JK, Madsen M. Hospital variation in mortality after first acute myocardial infarction in Denmark from 1995 to 2002: lower short-term and 1-year mortality in high-volume and specialized hospitals. Med Care 2005;43:970-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schneeweiss S. Sensitivity analysis and external adjustment for unmeasured confounders in epidemiologic database studies of therapeutics. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2006;15:291-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yeomans ND, Tulassay Z, Juhasz L, Racz I, Howard JM, van Rensburg CJ, et al. A comparison of omeprazole with ranitidine for ulcers associated with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Acid Suppression Trial: Ranitidine versus Omeprazole for NSAID-associated Ulcer Treatment (ASTRONAUT) Study Group. N Engl J Med 1998;338:719-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shore PA, Brodie BB, Hogben CA. The gastric secretion of drugs: a pH partition hypothesis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1957;119:361-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oosterhuis B, Jonkman JH. Omeprazole: pharmacology, pharmacokinetics and interactions. Digestion 1989;44(suppl 1):9-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hollander D, Dadufalza VD, Fairchild PA. Intestinal absorption of aspirin. Influence of pH, taurocholate, ascorbate, and ethanol. J Lab Clin Med 1981;98:591-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernandez-Fernandez FJ. Might proton pump inhibitors prevent the antiplatelet effects of low- or very low-dose aspirin? Arch Intern Med 2002;162:2248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lichtenberger LM, Ulloa C, Romero JJ, Vanous AL, Illich PA, Dial EJ. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug and phospholipid prodrugs: combination therapy with antisecretory agents in rats. Gastroenterology 1996;111:990-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robinson M, Horn J. Clinical pharmacology of proton pump inhibitors: what the practising physician needs to know. Drugs 2003;63:2739-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ho PM, Maddox TM, Wang L, Fihn SD, Jesse RL, Peterson ED, et al. Risk of adverse outcomes associated with concomitant use of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors following acute coronary syndrome. JAMA 2009;301:937-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zuern CS, Geisler T, Lutilsky N, Winter S, Schwab M, Gawaz M. Effect of comedication with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) on post-interventional residual platelet aggregation in patients undergoing coronary stenting treated by dual antiplatelet therapy. Thromb Res 2010;125:e51-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilard M, Arnaud B, Le Gal G, Abgrall JF, Boschat J. Influence of omeprazole on the antiplatelet action of clopidogrel associated to aspirin. J Thromb Haemost 2006;4:2508-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilard M, Arnaud B, Cornily JC, Le Gal G, Lacut K, Le Calvez G, et al. Influence of omeprazole on the antiplatelet action of clopidogrel associated with aspirin: the randomized, double-blind OCLA (Omeprazole CLopidogrel Aspirin) study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51:256-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Charlot M, Ahlehoff O, Norgaard ML, Jorgensen CH, Sorensen R, Abildstrom SZ, et al. Proton-pump inhibitors are associated with increased cardiovascular risk independent of clopidogrel use: a nationwide cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2010;153:378-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Donoghue ML, Braunwald E, Antman EM, Murphy SA, Bates ER, Rozenman Y, et al. Pharmacodynamic effect and clinical efficacy of clopidogrel and prasugrel with or without a proton-pump inhibitor: an analysis of two randomised trials. Lancet 2009;374:989-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhatt DL, Cryer BL, Contant CF, Cohen M, Lanas A, Schnitzer TJ, et al. Clopidogrel with or without omeprazole in coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1909-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yasuda H, Yamada M, Sawada S, Endo Y, Inoue K, Asano F, et al. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients receiving dual antiplatelet therapy after coronary stenting. Intern Med 2009;48:1725-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Catella-Lawson F, Reilly MP, Kapoor SC, Cucchiara AJ, DeMarco S, Tournier B, et al. Cyclooxygenase inhibitors and the antiplatelet effects of aspirin. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1809-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Summary data for propensity score matched cases and controls

Distribution of probabilities of treatment with proton pump inhibitors in propensity score matched model