Abstract

The current study examined the longitudinal stability and invariance of psychopathic traits in a large community sample of male twins from ages 17 to 23. Participants were assessed across six years to gauge the stability and measurement invariance of the Minnesota Temperament Inventory (MTI), a Cleckley-based measure of psychopathic personality traits, and how family functioning and externalizing behavior were linked to these traits. A latent variable approach was used to model the structure of the MTI and provide a statistical test of measurement invariance across time. The results revealed support for invariance and moderate to strong stability of the MTI factors, which showed significant associations with the external correlates in late adolescence but not early adulthood.

Keywords: Minnesota Temperament Inventory, Psychopathy, personality traits, Family functioning, Externalizing, Structural equation modeling

The extension of the psychopathy construct to children and adolescents has yielded promising results in regard to reliably identifying a subgroup of youth who manifest emotional deficits and related severity and stability of antisocial behavior. There is now evidence that psychopathy-related traits exist in child and adolescent samples (Frick et al., 2003; Lynam et al., 2007) and have a similar latent structure (Jones et al., 2006; Neumann et al., 2006) as well as associations with external correlates (Lynam & Gudonis, 2005) as found in adult samples (Hare & Neumann, 2008). Moreover, behavior genetic studies in children (Viding et al., 2007) and adolescents (e.g., Taylor et al., 2003) have demonstrated that a common genetic factor can account for the covariation in psychopathic trait domains reflecting antisocial tendencies and emotional detachment. Similarly, Larsson et al. (2007) recently reported that interpersonal, affective, impulsive, and antisocial features of psychopathy all load onto a single genetic factor in a large sample of adolescent twins. These studies highlight the meaningful structural, predictive, and genetic basis of psychopathic traits in youth.

Studies on the stability of psychopathy-related traits in youth are also an important step in this area of research, and can help in furthering our understanding of the emergence and development of psychopathic personality. For example, such studies afford an examination as to whether different facets of psychopathy follow distinct developmental trajectories (Blonigen et al., 2006), as well as reveal the degree to which psychopathic traits remain stable during developmental transitions that are marked by significant life changes. In this regard, Frick, Kimonis, Dandreaux, and Farell (2003) assessed psychopathic traits via parent, teacher, and self-report on the Antisocial Process Screening Device (Frick & Hare, 2001) across 2, 3, and 4 years in a sample of youth in the third, fourth, sixth and seventh grades at initial assessment (N = 98). Parent-rated stability was high (intra-class correlation coefficients = .80–.88) across 2–4 years, whereas cross-informant stability was in the moderate range (Frick et al., 2003). Similarly, others (e.g., Blonigen et al., 2006; Loney, Taylor, Butler, & Iacono 2007; Lynam, Caspi, Moffitt, Loeber, & Stouthamer-Loeber, 2007) have found moderate stability of psychopathic traits from adolescence to adulthood, while other research has noted that there is also is a smaller group of youth that change in personality during these transitions (Andershed, 2010). Collectively, however, it appears psychopathic traits are relatively stable from childhood to adolescence and from adolescence to adulthood.

One limitation of the developmental stability studies, however, is that they have relied upon an observed or manifest variable data analytic approach (Frick et al., 2003; Loney et al., 2007; Lynam et al., 2007). In contrast, a latent variable structural equation modeling (SEM) approach is more powerful for mathematically representing and understanding the structure of a measure designed to assess a given construct, as well as determining the relations among latent variables (Waller & Tomarken, 2005). In particular, the latent variable (LV) approach allows investigators to statistically test whether a set of manifest variables are valid indicators of specific LVs (Hoyle, 1995). For example, a specific LV (e.g., visual reasoning) is hypothesized to be responsible for generating the correlations among a specific set of manifest variables (e.g., find missing objects in pictures, join separately colored cubes to form designs). The strength of LV models is that they represent the common variance in a set of manifest variables separately from both unique and error-related variances based on precise item-to-factor model specifications (Bentler, 1980, 1995) and, therefore, allow for precise estimation of the association between factors (e.g., dimensions of psychopathy) for a particular instrument. Based on these strengths of an LV approach, they can assist in meeting recent recommendations that psychological measures be shown to represent homogeneous constructs (Smith, McCarthy, & Zapolski, 2009).

In addition, a LV approach may be optimal for testing if there are differential levels of stability across individual facets or trait dimensions of psychopathy from adolescence to young adulthood. For example, the findings of Lynam et al. (2007) suggested that facets of psychopathy marked by antisocial tendencies may be more stable, in a relative sense, than facets marked by emotional detachment. In contrast, Blonigen et al. (2006) reported that antisocial tendencies may be less stable, in an absolute sense, than interpersonal traits over this time frame (i.e., exhibit more mean-level change). Both studies, however, used a manifest variable approach; thus, it remains to be seen whether these differential patterns of stability would also be observed using a LV approach that is able to parse the common variance in each of these dimensions from their unique or error-related variances.

In contrast to the manifest variable studies discussed above, Obradović and colleagues (2007) used a LV approach to examine the temporal stability of a core feature of psychopathy (“interpersonal callousness”) in a large cohort of inner-city youth followed annually from ages 8 to 16. The latent variable approach allowed for demonstration of longitudinal invariance in the measurement of interpersonal callousness over a 9-year period, and reported moderate stability in these traits over this timeframe. Despite their sophisticated modeling approach and large longitudinal sample, this study focused on just the interpersonal/affective facet of psychopathy. Additional studies are needed that also examine the impulsivity and overt antisocial behavior that some theorists view as important to the conceptualization of the psychopathy construct (Hare & Neumann, 2008; Viding et al., 2007).

As highlighted by the Obradovic´ et al. (2007) study, a second limitation of the majority of stability studies is that they have not examined whether the traits assessed at baseline can be considered structurally equivalent to these ‘same’ traits assessed at a later time point (but see Witt, Donnellan, Blonigen, Krueger, & Witt, 2009). This is a critical assumption to test, especially given on-going development of personality in youth. In other words, investigators need to ascertain whether the psychopathy-related trait items on a given measure at one time point can be considered (statistically) equivalent (or invariant) to these same items at follow-up, suggesting that the latent trait factors underlying the observed item covariances reflect the same theoretical construct across time. To do this, one needs to rely on SEM approaches that involve LVs. This approach involves constraining items that load on a given factor to be equal to their respective items that are set to load on the same factor at follow-up. If the constrained parameter estimates and model fit are both good, then it is reasonable to suggest that the latent factor which underlies a set of item covariances reflects the same theoretical construct across time. Thus, an SEM approach may be optimal for investigating developmental trends in psychopathic traits during critical junctures in the life-course (e.g., transition into adulthood). That is, evidence of invariance allows investigators to be confident that a specific measure is performing similarly in assessing a given construct at different age periods.

A third limitation of previous stability studies concerns potential temporal relations among various psychopathy trait domains. Specifically, no stability studies have attempted to examine whether various psychopathy trait dimensions (e.g., emotional detachment vs. antisocial tendencies), might have theoretically informative cross-lag effects over time (e.g., Time 1 factor X predicting increases in Time 2 factor Y, controlling for Time 1 effects of factor Y). Some authors have proposed that certain psychopathic traits (e.g., callous affect) may cause other features of psychopathy, such as overt antisocial tendencies (e.g., Cooke et al., 2004, but see Neumann et al., 2005 for a contrasting view). Nevertheless, while traits such as callousness can lead to antisocial behaviors at some future point (e.g., Vitacco et al., 2002), longitudinal studies have also shown that antecedent antisocial tendencies predict the stability of other psychopathy-related traits (Frick et al., 2003), and covary significantly with future traits reflecting interpersonal and affective psychopathy features (Larsson et al., 2007). To date, the longitudinal and behavior genetic (e.g., Viding et al., 2007) findings suggest that the interpersonal and affective components of psychopathy exhibit developmental ties to more overt antisocial features (Hare & Neumann, 2008). As such, it is reasonable to hypothesize that there may be reciprocal effects between these psychopathy domains (each leading to changes in the others), or at minimum, strong concurrent associations at each assessment.

Finally, the stability studies by Frick et al. (2003) and Lynam et al. (2007) have highlighted that various contextual developmental factors may help account for the stability of psychopathy traits over time. In particular, these studies indicated that factors associated with the family environment and functioning (e.g., degree of cohesion and support) and externalizing behavior were linked to the stability of psychopathic traits. Lynam and colleagues (2007) demonstrated that family structure and, to a lesser extent, behavioral impulsivity were significant predictors of later psychopathy scores independent of psychopathic traits initially assessed. Along these same lines, Frick et al. (2003) found quality of parenting and a child’s level of conduct problems were consistent predictors of stability. These two domains of variables (family and externalizing) may be considered contextual factors that can play a contributory role in altering both the expression and developmental stability of psychopathic traits. However, in each of these studies, the family and externalizing factors played relatively minor roles in accounting for subsequent psychopathic traits compared to previous trait levels. Thus, the current study seeks to replicate the findings from Frick et al. and Lynam et al., but also test whether more robust representations (i.e., latent variables) of these contextual variables may have more influential effects on the expression of psychopathic traits. This latter issue may be particularly relevant for externalizing, given that this construct has been specifically theorized as representing a broad (latent) vulnerability to disinhibition that transcends its specific indicators (Krueger et al., 2007).

To address various limitations in the literature, the present study used a large community-based sample of twins to assess the longitudinal stability of psychopathy traits over a 6-year period between late adolescence and young adulthood (ages 17 to 23) – a formative period of development marked by a host of significant life changes (Arnett, 2000). Specifically, we examined the stability of traits of emotional detachment and antisocial deviance, indexed by the Minnesota Temperament Inventory (MTI), using an SEM-based approach. The advantages of using the MTI include: (1) it was designed to tap Checkley-based traits of psychopathy, (2) represents two homogeneous psychopathy factors (Detachment & Antisocial; Loney et al., 2007), and (3) has been shown to tap a moderate genetic component. As part of our broad objectives, we also tested if there were significant temporal relations across the MTI psychopathy factors over time in the form cross-lagged effects (e.g., Do features of emotional detachment in adolescence predict antisocial tendencies in adulthood after controlling for antisocial tendencies in adolescence?). Finally, we explored how constructs of family functioning and externalizing behavior were linked to these psychopathic traits in adolescence.

It is important to note that the stability of the trait dimensions measured by the MTI was previously examined in this sample (Loney et al., 2007). That study assessed the 6-year stability of the emotional detachment and antisocial tendencies subscales of the MTI from adolescence to adulthood and found moderate stability across this time frame: correlation coefficients for emotional detachment and antisocial tendencies were .40 and .41, respectively. Given these moderate stability estimates, the authors suggested the need for a more detailed developmental model including variables such as child and family factors, which is addressed in the current study. Moreover, the current study extends prior work on the MTI through the use of both an SEM approach and examination of cross-lagged effects. The former issue is particularly noteworthy given that an SEM approach affords explicit tests of measurement invariance in psychopathic traits over time. Testing if a measure is invariant over time (both in terms of configural and metric invariance) is often overlooked in longitudinal studies of psychopathy, yet is essential to properly gauge the stability of psychopathic traits from adolescence to adulthood.

Based on the previous literature (Obradovic´ et al., 2007) as well as previous research with this sample (Taylor et al., 2003), we predicted that the MTI would be invariant over time and that the MTI factors would have moderate-to-strong stability. We did not have any predictions regarding cross-lag effects among the MTI factors, given this issue has not previously been investigated. Finally, based on prior research, we predicted that the family and externalizing factors would be significantly associated with the MTI factors, but would be weaker than the stability associations between respective MTI factors (e.g., Detachment at Time 1 to Detachment at Time 2).

Method

Participants

Data for the current study were taken from the Minnesota Twin Family Study, a longitudinal investigation of reared together twins and their parents (Iacono, Carlson, Taylor, Elkins, & McGue, 1999), focused primarily on the etiology of substance use disorders, and related forms of psychopathology. Although the Minnesota Twin Family Study included both male and female twins, the females were not asked to complete the psychopathy measure used in the current study; hence, this report deals only with the male participants. Data used in the present study was collected from a cohort of adolescent male twins (N = 315) born between the years 1972–1978, and identified via Minnesota public birth records and recruited for participation the year the twins turned 17-years-old. Among eligible families identified during recruitment, 83% agreed to participate. Parents of participating and non-participating families were not found to differ in terms of rates of psychopathology or SES (Iacono et al., 1999). Twin families were excluded from participation if either twin had a cognitive or physical disability that would hinder their participation in the day-long, in-person assessment, or if they lived further than a one-day drive to the University of Minnesota. The sample is representative of the Minnesota population in terms of ethnicity and SES (Holdcraft & Iacono, 2004). Note that the total N for the current study differed slightly from that of Loney et al. (2007) given that the models in the current study relied on those with complete data at both time points.

Measures

Psychopathy

At ages 17 and 23, psychopathy features were assessed via self-report using the Minnesota Temperament Inventory (MTI) – a 19-item research-based measure created before the development of many other currently used psychopathy rating scales. It contains 16 psychopathy items that were designed to tap the hallmark features of psychopathy originally outlined by Cleckley (1976). For the current study, we examined the two-factor, 13-item model reported by Loney et al. (2007). Specifically, these MTI items stem from two underlying psychopathy dimensions, which correspond in content to the Antisocial tendencies/lifestyle (or behavioral) and emotional Detachment (or affective) dimensions contained on other established psychopathy measures. Items on the MTI are rated on a 4-point scale (1 = this is not at all true of me; 4 = this is very true of me). Higher scores indicate higher levels of the scale’s dimension.

Psychopathology

Participants and their parents were interviewed separately for symptoms of psychopathology by trained interviewers with at least a B.A. in Psychology. Lifetime criteria of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) were assessed in adolescents via a modified version of the Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents - Revised, parent version (DICA-R-P; Herjanic & Reich, 1982; Reich & Welner, 1988). In almost all cases, the twins’ mother was the parent informant on the DICA-R-P. Adolescents were independently interviewed using the child version of the same diagnostic interview (DICA-R-C) to assess lifetime criteria of ADHD and ODD. Adolescents were administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (SCID-II; Spitzer, Williams, Gibbon, & First, 1987) to assess symptoms of conduct disorder. A modified version of the expanded Substance Abuse Module of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (Robins et al., 1988) was used to assess lifetime criteria of alcohol dependence.

Diagnostic symptoms of these disorders were assigned using DSM-III-R criteria by a team of at least two advanced clinical graduate students during a case conference. Symptoms were entered into a database and computer algorithms (based on DSM-III-R criteria) were employed to produce study diagnoses. For adolescents, a symptom of a disorder was counted toward the diagnosis if either the child or the parent informant endorsed it at threshold level as is typical in a best-estimate strategy (Bird, Gould, & Staghezza, 1992). These procedures produced diagnostic reliability coefficients (kappa) of 1.00 for alcohol use disorders, .84 for ADHD, .75 for CD, and .71 for ODD. To facilitate the analytical plan, symptom counts (sum of the number of symptoms met at threshold level) were tabulated for alcohol dependence, ADHD, and a combined variable for CD/ODD (sum of symptoms of both disorders). This latter variable reflects the fact that ODD was not controlled for when assessing CD. More importantly, latent variable research by Fergusson et al. (1994), using a community sample, and Hewitt et al. (1997), using a twin sample, have provided support for modeling CD and ODD as indicators of an latent construct reflecting disruptive pathology. Relatedly, Diamantopoulou et al. (2010) provided support for a model that suggests continuity of antisocial behavior from more moderate disruptive behaviors (ODD and ADHD) to more severe (CD). More generally, the combination of indicators used in the current study is consistent with the Externalizing LV as discussed by Krueger and Markon (2006).

Family Environment

At age 17, twins completed the Family Environment Scale (FES; Moos & Moos, 1986) which contains 90 items that tap different aspects of family life (e.g., time spent together; help and support of each other; strictness of rules; focus on achievement). Items were rated on a 4-point scale (anchored at “definitely true” and “definitely false”). Based on prior literature on family factors related to psychopathic traits, the Cohesion and Support scales from the FES were used to characterize the extent to which family members were close (e.g., had feelings of togetherness; spent time together) and supported one another (e.g., backed each other up; helped each other), respectively. Higher scores on each scale indicate higher levels of each characteristic. Twins also completed the FACES III (Olson, Porther, & Lavee, 1985) measure at age 17, which also assesses family functioning. There are 20 items rated on a 5-point scale (1 = Almost never; 5 = Almost always) that tap adaptability and cohesion facets of family environment. The Cohesion scale was used as an additional measure of that dimension and contained item regarding helpfulness of family members and togetherness.

Data Analytic Plan

Based on the Loney et al. (2007) results for the Minnesota Temperament Inventory (MTI), the current study specified the MTI item-to-latent variable relations as follows: Detachment (item #s 8, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17) and Antisocial (6, 7, 9, 10, 11,12, 19). Since the items are ordinal, the robust weighted least squares estimation procedure (WLSMV) provided by the Mplus modeling software (Muthén & Muthén, 2001) was used for all analyses. In addition, the Mplus routine for sample clustering (analysis type = complex) was employed with family as the clustering variable, given the use of a twin sample. (Notably, there was little difference in the results whether the clustering routine was used or not.) For the current study, there were three sets of analyses. First, the Time 1 (age 17) and Time 2 (age 23) MTI items were each analyzed separately to check the adequacy of fit for the two-factor measurement model at each time point. Model fit was determined using a two-index strategy recommended by Hu and Bentler (1999). The Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) was used to assess incremental fit, and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) was used to gauge absolute fit. Assuming good model fit, the next analysis involved a test of strong invariance (factor loadings and item thresholds constrained to be equal) for the MTI items across Times 1 and 2. In addition, the Time 1 MTI factors served as predictors of the Time 2 MTI factors to gauge the latent stability effects, and also to examine if their were any meaningful cross-lag effects (e.g., Detachment at Time 1 predicting Antisocial at Time 2). For the final model analysis, the ODD, CD, ADHD, and alcohol dependent variables were set to load onto an Externalizing LV, and the cohesion (FES, FACES) and support (FES) variables were set to load onto a (positive) Family Functioning LV. These LVs were allowed to correlate with the Time 1 MTI factors and also served as predictors of the Time 2 MTI factors, along with the Time 1 MTI factors. Standard SEM approaches were used for determining parameter significance. (Note that the MTI item invariance constraints were also employed for this final model). The sample N for the MTI model analyses was 315 (those participants with MTI items at both Time 1 and Time 2). For the final model, which included the two external correlate LVs, the sample N was 252. There were no significant differences between those with versus without the externalizing or family functioning variables in terms of the MTI variables and similarly for age or education (results available on request).

Results

For descriptive purposes, means and standard deviations for the manifest variable scale scores are provided in Table 1. Scale internal consistency assessed via Cronbach’s alpha ranged from .60 (Externalizing) to .87 (Family Functioning). However, while frequently employed, the use of alpha is problematic since it is influenced by scale length, and more importantly, is not a measure of item homogeneity or unidimensionality (Schmitt, 1996). Based on discussion of Mean Inter-item Correlations (MICs) in Simms and Watson (2007), the MIC results for each scale displayed in Table 1 were all acceptable (i.e., between .15–.50), although the MIC for the Family Functioning composite was somewhat large, and suggests some item redundancy.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for MTFS variables

| Variables | Mean | SD | Min | Max | MIC | alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MTI Scales | ||||||

| Detachment (Time 1) | 9.88 | 2.90 | 6 | 19 | .27 | .70 |

| Antisocial (Time 1) | 10.70 | 3.31 | 7 | 24 | .32 | .76 |

| Detachment (Time 2) | 8.49 | 2.39 | 6 | 24 | .24 | .66 |

| Antisocial (Time 2) | 8.70 | 2.35 | 7 | 28 | .28 | .73 |

| Family Functioning | .68 | .87 | ||||

| Cohesion (FACES) | 33.55 | 6.26 | 12 | 50 | ||

| Cohesion (FES) | 7.03 | 2.14 | 0 | 9 | ||

| Support (FES) | 10.54 | 2.44 | 3 | 15 | ||

| Externalizing Symptoms | .30 | .60 | ||||

| ODD+CD (Time 1) | 2.24 | 1.97 | 0 | 13 | ||

| ADHD (Time 1) | 0.88 | 1.74 | 0 | 10 | ||

| Alcohol Dependence (Time 1) | 0.35 | 0.94 | 0 | 7 |

Note. MIC = Mean inter-item correlation

Measurement Model: Minnesota Temperament Inventory (MTI)

The CFA results for the MTI psychopathy items at age 17 Time 1 revealed excellent fit for the two-factor model, TLI = .96, RMSEA = .05 (χ2(28) = 61.92). The age 23 Time 2 results for the MTI psychopathy items also revealed excellent fit for the two-factor model, TLI = .95, RMSEA = .05 (χ2(28) = 55.96). All item-to-factor loadings were significant (ps < .05–.001). The range of factor loadings were as follows: Age 17 (time 1): Detachment = .54 – .70, Antisocial = .60 – .78; Age 23 (time 2): Detachment = .54 – .67, Antisocial = .47 – .80. The latent correlations between the Detachment and Antisocial factors at age 17 Time 1 (r = .71, p < .0001) and age 23 Time 2 (r = .72, p < .0001) were large, suggesting strong links between emotional detachment and overt antisocial behavior. Note that a one-factor model was also tested for comparison purposes, but resulted in a poorer fit (TLI = .91–.92, RMSEA = .07–.09), compared to the two-factor model.

Time-1/Time-2 Minnesota Temperament Inventory (MTI) Invariance Model

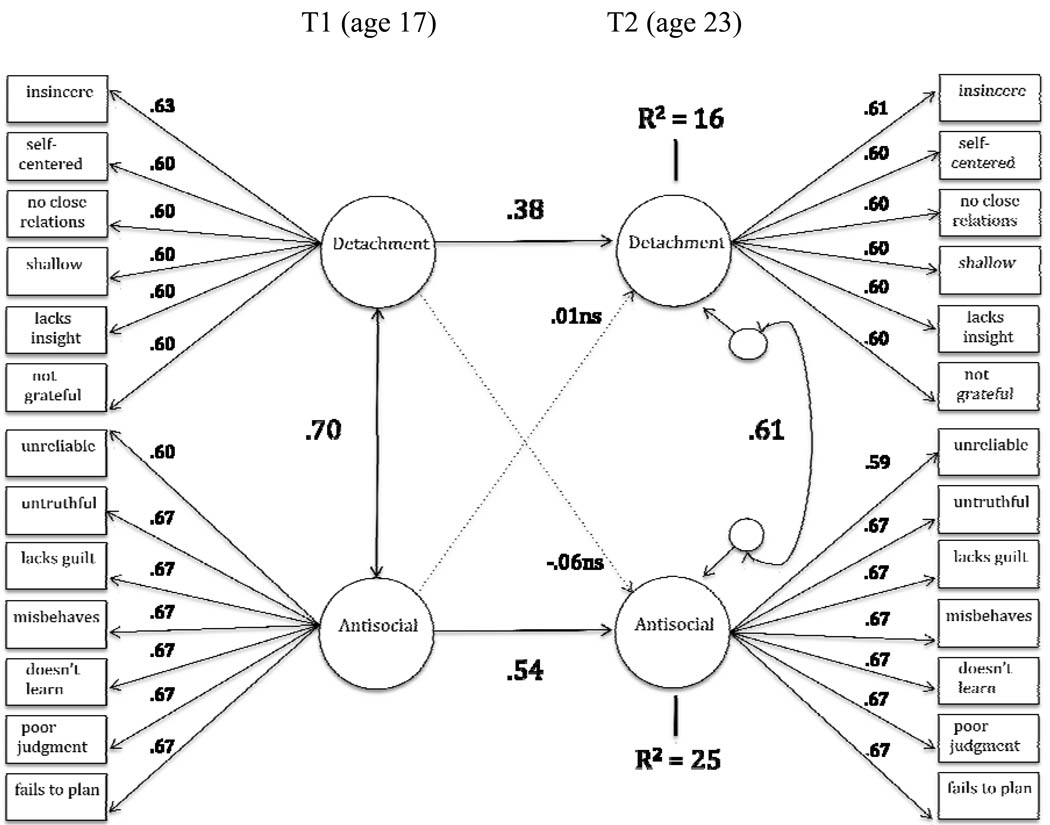

The SEM testing for strong invariance of the MTI psychopathy items across time (constrained age 17 Time 1 and age 23 Time 2 factor loading and item thresholds) indicated excellent model fit, TLI = .95, RMSEA = .05 (χ2(47) = 80.83). All item-to-factor loadings were significant (ps < .05–.001). Figure 1 displays the standardized structural parameters for these results, and indicates that there was moderate stability between the latent Detachment factors (.38) and strong stability between the latent Antisocial factors (.54). Also, there were strong concurrent correlations between the MTI psychopathy factors at each time point (ps < .05–.01). There were no significant cross-lag effects (ps > .05). Thus, the results highlight that males who reported more psychopathic emotional detachment also reported increased overt antisocial behavior at age 17 and similarly for the follow up at age 23. At the same time, emotional detachment at age 17 did not result in the temporal prediction of antisocial behavior at age 23 and visa versa.

Figure 1.

Structural Equation Model: Invariance of MTI Items Across Time (Note. All model parameters significant [p’s < .05–.001] unless denoted as nonsignificant-ns.)

Notably, the constrained model fit results did not differ from the unconstrained model fit (TLI = .95, RMSEA = .05), providing further evidence for invariance of the MTI psychopathy items over time. Also, there was no difference in model fit when the cross-lag effects were removed from the model (TLI = .95, RMSEA = .05), indicating that the MTI Detachment and Antisocial factors can be understood in terms of concurrent covariation, as opposed to one factor being antecedent to another.

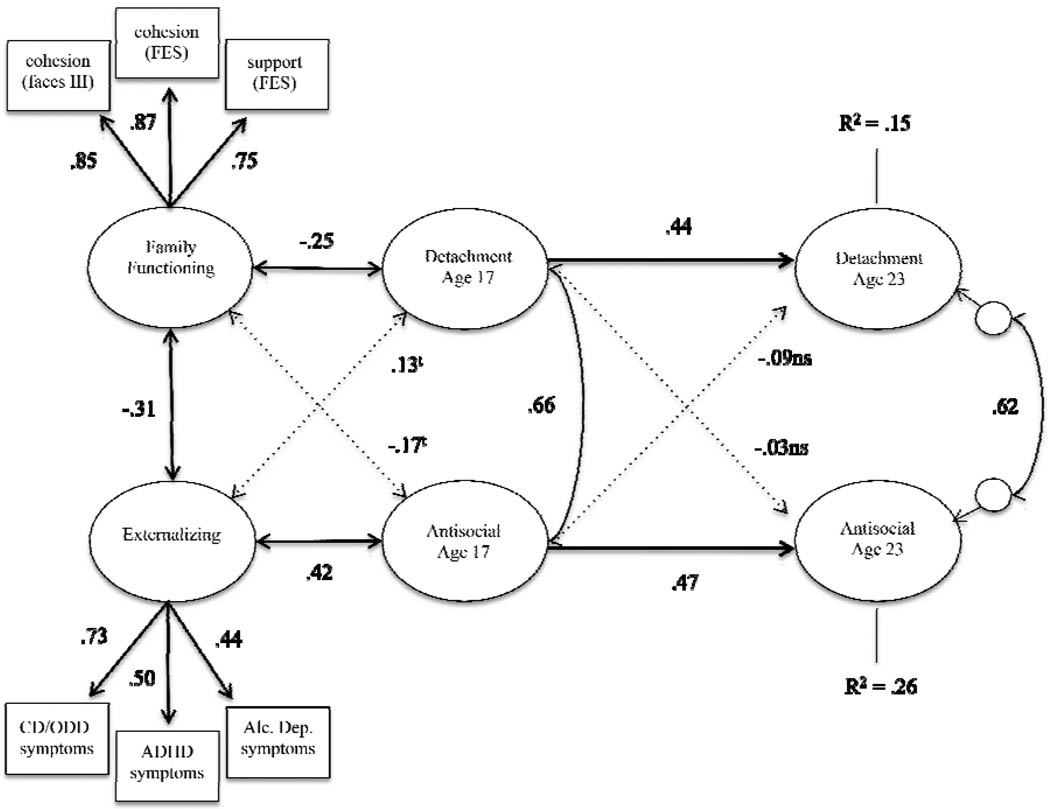

MTI, Family Functioning, Externalizing Model

Results for the final SEM again indicated good model fit, TLI = .94, RMSEA = .05 (χ2(47) = 71.88). The MTI Detachment factor at age 17 Time 1 was significantly correlated with the Family Functioning factor (r = −.25, p < .01), and the MTI Antisocial factor at age 17 Time 1 was significantly correlated with the Externalizing factor (r = .42, p < .001). The Family and Externalizing factors were significantly correlated (r = −.31, p < .01). The factor correlations between the Family and MTI Antisocial (r = −.17) and Externalizing and MTI Detachment (r = .13) factors did not reach conventional levels of significance (p = .07–.09). Finally, there were no significant predictive effects of the Family or Externalizing factors on the age 23 Time 2 MTI Detachment or Antisocial factors. That is, conventional SEM statistical procedures for determining parameter significance indicated that these latter parameters were not different from zero (ps > .05). As such, only the baseline MTI psychopathy factors were significant predictors of their respective follow-up MTI psychopathy factors.

Discussion

The present study used an SEM approach to examine the structural invariance and stability of Minnesota Temperament Inventory (MTI) based psychopathic traits during the formative transition from late adolescence (age 17) into young adulthood (age 23). An important implication of using this approach is that it more precisely estimated the structural parameters, and thus the developmental patterns, that characterize features of psychopathy (emotional detachment & overt antisocial behavior) across the 17 to 23 year old period. To this extent, the findings allow investigators to have greater confidence in the magnitude of stability for the MTI psychopathy factors across this timeframe, as opposed to the stability estimates of these factors when based on manifest variable approaches, which are influenced by measurement error.

The results revealed excellent fit for the MTI two-factor (Detachment-Antisocial) model, and indicated that the psychopathy item parameters of this measure (factor loadings and thresholds) were invariant across time. Collectively, these findings provide strong evidence for the structural validity for the Detachment and Antisocial psychopathy factors during the transition into adulthood. In this regard, the MTI factors showed moderate (Detachment) to strong (Antisocial) stability across time, which provides further support for the continuity of psychopathic features from late adolescence to young adulthood. In addition, at Time 1 (age 17) the positive family functioning factor was significantly negatively correlated with the Detachment factor, and the externalizing factor was positively associated with the Antisocial factor. These results are consistent with previous research (e.g., Frick et al., 2003; Lynam et al., 2007) and provide support for the construct validity of these factors in late adolescence. In addition, the pattern of differential associations of the family and externalizing factors with the MTI psychopathy factors suggest that they may play separate roles in influencing expression of psychopathic features of emotional detachment and overt antisociality.

Implications for the Development of Psychopathic Traits

From a developmental standpoint, there were several noteworthy findings from the present study. First, a large intercorrelation was detected between the Detachment and Antisocial factors within each time period. Thus, as measured by the MTI, these factors represent overlapping indicators of psychopathic personality in both late adolescence and early adulthood. Notably, strong intercorrelations between psychopathy factors have been previously identified in adolescent samples (Neumann et al., 2006), and is consistent with several different behavioral genetic studies during this developmental period, which have shown that the covariance between interpersonal, affective, and antisocial components of psychopathy can be largely accounted for in terms of a common genetic factor (Baker et al., 2007; Larsson et al., 2007; Taylor et al., 2003). Nevertheless, other behavioral genetic work with adolescent twin samples employing different measures of psychopathy have shown evidence of both common and unique genetic effects across interpersonal (e.g., fearless dominance), affective (e.g., callous unemotionality), and antisocial features of psychopathy (Blonigen et al., 2005; Larsson, Andershed, & Lichtenstein, 2006). While such findings suggest that the expression of psychopathy is multifaceted, they are not necessarily incompatible with a view that different components of psychopathy can perhaps be understood in terms of a global factor of dis-sociality (Neumann, Hare, & Newman, 2007). Importantly, such a view is consistent with recent hierarchical models of both Externalizing (Krueger et al., 2007) and PCL-R defined psychopathy (Patrick et al., 2006) through the estimation of global (higher-order) factors as well as independent dimensions of psychopathy.

Second, we did not find evidence for significant cross-lagged effects between the MTI Detachment and Antisocial psychopathy factors over time, only strong concurrent factor correlations. In other words, males who reported being emotionally detached from others also endorsed more overt antisocial behaviors, whether assessed at age 17 or age 23. However, there was no evidence that one of these psychopathic domains (e.g., emotional detachment) temporally predicted the other domain (overt antisociality). This pattern of findings may not be surprising given that past research has shown that models depicting causal relations between ostensibly distinct features of psychopathy can be accounted for by models demonstrating that such features are correlated manifestations of a common personality disturbance (Neumann, Vitacco, Hare, & Wupperman, 2005). On the other hand, prospective work by Frick et al. (2003) found that antisocial tendencies predicted the emergence of other psychopathic features (e.g., narcissism) over a 4-year period in non-referred youth from third to seventh grade. The apparent discrepancy of these findings with the present data is potentially explainable by the age differences across the samples such that temporal associations between different dimensions of psychopathy may vary over the course of development. For example, exposure to, or engagement in, overt antisocial behavior early in childhood may play a role in desensitizing affective experience (Hare & Neumann, 2005, 2008). In support of this hypothesis, a recent meta-analytic review of exposure to violent video games indicates that it is associated with longitudinal decreases in empathy and prosocial behavior (Anderson et al., 2010). Thus, it may behoove future longitudinal studies to examine if patterns of cross-trait/cross-time relations between psychopathy dimensions vary across different developmental epochs.

Third, the structural model that incorporated time 1 (age 17) factors of family functioning and externalizing found these empirically supported correlates of psychopathy to be significantly differentially associated with the MTI Detachment and Antisocial factors at age 17. However, these external correlates did not significantly predict the stability of these traits during the transition into adulthood at age 23. These findings are also inconsistent with Frick et al. (2003), which found indices of parenting and externalizing behavior to predict several different psychopathic features in childhood. However, as previously mentioned, the Frick et al. (2003) study differed from the current study in a number of way; most notably in terms of their different analytic approaches (latent versus manifest variables) and focus on different developmental periods. A longitudinal study by Lynam et al. (2007), which more closely matches the current study in terms of its focus on the transition from adolescence to adulthood, found that the majority of the external variables in their study had no effect on the stability of psychopathic traits, with the exception of modest effects of family structure and behavioral impulsivity. Nevertheless, both the current and previous findings indicate that family processes and externalizing behavior are significantly linked to the expression of psychopathic traits in late adolescence (age 17).

Implications for the Measurement of Psychopathic Traits

From the standpoint of measurement, the present findings provide strong support for the structural validity of the MTI two-factor (Detachment-Antisocial) model and invariance of this structure from late adolescence (age 17) into young adulthood (age 23). Furthermore, the present data indicated acceptable mean inter-item correlations among the items that comprise the MTI psychopathy factors – an important point given assertions that these statistics may provide a more reliable index of scale homogeneity than coefficient alphas (Schmidt, 1996). As Schmidt (1996) and others (Borsboom, 2008) have discussed, alpha is simply an indicator of how well a set of variables ‘hang’ together but does not reflect unidimensionality, given that any diverse set of positively correlated variables (e.g., IQ, education level, occupation) could provide acceptable alphas and yet involve multidimensional phenomenon. Item homogeneity (MICs) on the other hand does reflect unidimensional phenomenon. On balance, the current findings indicate that the Detachment and Antisocial factors of the MTI are unidimensional (i.e., homogenous). This is consistent with other self-report measures of psychopathy (Neumann & Declerq, 2009; Paulhus, Neumann, & Hare, in press), as well as the Psychopathy Checklist scales (Hare & Neumann, 2008) in demonstrating unidimensionality of the constituent factors of these instruments. As previously noted, consideration of this issue has implications for studying the developmental patterns that characterize psychopathic traits given that clear articulation of item-to-factor relations may yield more precise estimates of stability and change over time.

In addition, as discussed by Smith and colleagues (2009), the unidimensionality of scales are optimal when attempting to examine the convergent and discriminant relations between psychopathic traits and relevant external criteria. However, conformity to the strict specifications of SEM (e.g., confirmatory factor analysis) is by no means the sole basis for evaluating the internal structure and construct validity of a measure. Moreover, we do not mean to imply that instruments that allow for the construction of latent variables are necessarily better or more valid than ones that rely on manifest variables. Indeed, numerous scholars have noted that some omnibus personality inventories are a poor fit for confirmatory factor models (Neumann et al., 2008), often those based on exploratory factor models, which nonetheless show some replicable EFA results across multiple samples, and demonstrate criterion validity (Church & Burke, 1994; Grucza & Goldberg, 2007; Hopwood & Donnellan, in press; McCrae et al., 1996). Still, SEM-based approaches have broad measurement and structural implications (e.g., clear item-to-factor specification); therefore, further application of these approaches in developmental studies of psychopathy is recommended as it can more precisely estimate the magnitude of stability of psychopathic traits (as measured and conceptualized for a particular instrument).

Several limitations of the present study can be noted. First our results are based primarily on use self-report data. Similar to the issue of using SEM-based approaches, multi-method approaches to the estimation of both psychopathic traits and external criteria (see Blonigen et al., 2010) are optimal for identifying the manner in which contextual processes, such as the family structure, shape the development of psychopathy over time. Second, our sample included only male twins; thus, there is a need to examine the developmental and structural patterns in mixedgender samples. Third, our examination of external correlates was limited to the family environment and externalizing behavior factors. These factors, however, represent two of the more robust correlates of psychopathic features in adolescence (Lynam et al., 2007). Fourth, our interpretations must be limited to the timeframe of late adolescence (age 17) to young adulthood (age 23). The importance of this age period aside, the present findings may not characterize the developmental patterns during the formative years of early childhood (Frick et al., 2003; Barry et al., 2008).

In sum, the results provide good support for the two-factor (Detachment-Antisocial) Minnesota Temperament Inventory (MTI) model and the invariance of the item-to-factor relations in this model across adolescence into young adulthood. Furthermore, the MTI Detachment and Antisocial factors showed moderate to strong stability across time, and were associated with family and externalizing factors at late adolescence. We recommend future longitudinal studies of psychopathic traits employ similar SEM-based approaches to estimate the patterns of stability and change in psychopathic traits over time. Additionally, the current study examined a critical period in the life-course of personality development (Roberts & Mroczek, 2008). Furthermore, given that this is one of the first studies in the psychopathy literature to examine cross-lagged effects, we encourage future efforts to estimate the within- and across-time relations between correlated psychopathic trait domains (e.g., Interpersonal, Affective, Impulsive Lifestyle, overt Antisocial), as well as explore whether other external correlates relevant to the expression of psychopathic traits during adolescence (e.g., peer relations; Munoz, Kerr, & Besic, 2008) may moderate the course of antisocial and other psychopathic tendencies during the transition into adulthood.

Figure 2.

Structural Equation Model: Family Functioning and Externalizing Associations with MTI Factors (Note. All model parameters significant [p’s < .05–.001] unless denoted as nonsignificant-ns.)

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Health Grants R37 DA005147 and U01 DA024417 awarded to William G. Iacono, principal investigator.

Contributor Information

Craig Neumann, University of North Texas.

Megan Wampler, Florida State University.

Jeanette Taylor, Florida State University.

Daniel M. Blonigen, Center for Health Care Evaluation, Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System and Stanford University School of Medicine

William G. Iacono, University of Minnesota–Twin Cities

References

- Andershed H. Stability and change of psychopathy traits: What do we know? In: Lynam D, Salekin R, editors. Handbook of child and adolescent psychopathy. New York: Guilford; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CA, Shibuya A, Ihori N, Swing EL, Bushman BJ, Sakamoto A, Rothstein HR, Saleem M. Violent video game effects on aggression, empathy, and prosocial behavior in eastern and western countries: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2010;136:151–173. doi: 10.1037/a0018251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55:469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker LA, Jacobson KC, Raine A, Lozano DI, Bezdjian S. Genetic and environmental bases of childhood antisocial behavior: a multi-informant twin study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:219–235. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.2.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry TD, Barry CT, Deming AM, Lochman JE. Stability of Psychopathic Characteristics in Childhood: The Influence of Social Relationships. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2008;35:244–262. [Google Scholar]

- Bird HR, Gould MS, Staghezza B. Aggregating data from multiple informants in child psychiatry epidemiological research. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1992;31:78–85. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199201000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blonigen DM, Hicks BM, Krueger RF, Patrick CJ, Iacono WG. Psychopathic personality traits: Heritability and genetic overlap with internalizing and externalizing psychopathology. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35:637–648. doi: 10.1017/S0033291704004180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blonigen DM, Hicks BM, Krueger RF, Patrick CJ, Iacono WG. Continuity and change in psychopathic traits as measured via normal range personality: A longitudinal-biometric study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:85–95. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.1.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blonigen DM, Patrick CJ, Douglas KS, Poythress NG, Skeem JL, Lilienfeld SO, Edens JF, Krueger RF. Multi-method assessment of psychopathy in relation to factors of internalizing and externalizing from the Personality Assessment Inventory: The impact of method variance and suppressor effects. Psychological Assessment. 2010;22:96–107. doi: 10.1037/a0017240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church AT, Burke PJ. Exploratory and confirmatory tests of the Big Five and Tellegen’s three- and four-dimensional models. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;66:93–114. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.66.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamantopoulou S, Verhulst FC, van der Ende J. Testing developmental pathways to antisocial personality problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2010;38:91–103. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9348-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Lynskey MT. Structure of DSM-III-R criteria for disruptive childhood behaviors: confirmatory factor models. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1994;33(8):1145–1155. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199410000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Hare RD. The antisocial process screening device (APSD) Toronto: Multi-Health Systems; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Kimonis ER, Dandreaux DM, Farell JM. The 4-year stability of psychopathic traits in non-referred youth. Behavioral Sciences and the Law. 2003;21:713–736. doi: 10.1002/bsl.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grucza RA, Goldberg LR. The comparative validity of 11 modern personality inventories: Predictions of behavioral acts, informant reports, and clinical indicators. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2007;89:167–187. doi: 10.1080/00223890701468568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare RD, Neumann CS. Structural models of psychopathy. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2005;7:57–64. doi: 10.1007/s11920-005-0026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare RD, Neumann CS. Psychopathy as a clinical and empirical construct. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:217–246. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herjanic B, Reich W. Development of a structured psychiatric interview for children: Agreement between child and parent on individual symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1982;10:307–324. doi: 10.1007/BF00912324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt JK, Silberg JL, Rutter M, Simonoff E, Meyer JM, Maes H, et al. Genetics and developmental psychopathology: 1. Phenotypic assessment of the Virginia Twin Study of adolescent behavioral development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1997;38(8):943–963. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood CJ, Donnellan MB. How should the internal structure of personality inventories be evaluated? Personality and Social Psychology Review. doi: 10.1177/1088868310361240. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Markon KE, Patrick CJ, Benning SD, Kramer MD. Linking antisocial behavior, substance use, and personality: An integrative quantitative model of the adult externalizing spectrum. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:645–666. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.4.645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson H, Andershed H, Lichtenstein P. A genetic factor explains most of the variation in the psychopathic personality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:221–230. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson H, Tuvblad C, Rijsdijk FV, Andershed H, Grann M, Lichtenstein P. A common genetic factor explains the association between psychopathic personality and antisocial behavior. Psychological Medicine. 2007;37:15–26. doi: 10.1017/S003329170600907X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson H, Viding E, Rijsdijk FV, Plomin R. Relationships between parental negativity and childhood antisocial behavior over time: A bidirectional effects model in a longitudinal genetically-informative design. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:633–645. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9151-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loney BR, Taylor J, Butler MA, Iacono WG. Adolescent psychopathy features: 6-year temporal stability and the prediction of externalizing symptoms during the transition to adulthood. Aggressive Behavior. 2007;33:242–252. doi: 10.1002/ab.20184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Longitudinal evidence that psychopathy scores in early adolescence predict adult psychopathy. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:155–165. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR, Gudonis L. The development of psychopathy. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:381–407. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, Moos BS. Family Enviornment Scale manual. 2nd Ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Munoz LC, Kerr M, Besic N. The peer relationships of youths with psychopathic personality traits. Criminal Justice & Behavior. 2008;35:212–227. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann CS, Hare RD, Newman JP. The super-ordinate nature of the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2007;21:102–117. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2007.21.2.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann CS, Kosson DS, Forth AE, Hare RD. Factor structure of the Hare Psychopathy Checklist: Youth Version (PCL: YV) in incarcerated adolescents. Psychological Assessment. 2006;18:142–154. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.18.2.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann CS, Malterer MB, Newman JP. Factor structure of the Psychopathic Personality Inventory (PPI): Findings from a large incarcerated sample. Psychological Assessment. 2008;20:169–174. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.20.2.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann CS, Vitacco MJ, Hare RD, Wupperman P. Re-construing the "Reconstruction" of psychopathy: A comment on Cooke, Michie, Hart & Clarke. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2005;19:624–640. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2005.19.6.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obradović J, Pardini DA, Long JD, Loeber R. Measuring interpersonal callousness in boys from childhood to adolescence: An examination of longitudinal invariance and temporal stability. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36:276–292. doi: 10.1080/15374410701441633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson DH, Portner J, Lavee Y. FACES III. St. Paul, MN: University of Minnesota; 1985. Family Social Science. [Google Scholar]

- Reich W, Welner Z. Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents - Revised: DSM-III-R Version (DICA-R) Washington University: St. Louis; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick CJ, Hicks BM, Nichol PE, Krueger RF. A bi-factor approach to modeling the structure of the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2007;21:118–141. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2007.21.2.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, Mroczek D. Personality trait change in adulthood. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2008;17(1):31–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00543.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt Uses and abuses of coefficient alpha. Psychological Assessment. 1996;8:350–353. [Google Scholar]

- Simms LJ, Watson D. The construct validation approach to personality scale construction. In: Robins RW, Fraley RC, Krueger RF, editors. Handbook of research methods in personality psychology. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 240–258. [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, McCarthy DM, Zapolski TC. On the value of homogeneous constructs for construct validation, theory testing, and the description of psychopathology. Psychological Assessment. 2009;21:272–284. doi: 10.1037/a0016699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M, First MB. Structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R personality disorders (SCID-II) New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J, Loney BR, Bobadilla L, Iacono WG, McGue M. Genetic and environmental influences on psychopathy trait dimensions in a community sample of male twins. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31(6):633–645. doi: 10.1023/a:1026262207449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomarken AJ, Waller NG. Structural equation modeling: Strengths, limitations, and misconceptions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:31–65. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Durrett CA. Categorical and dimensional models of personality disorder. Annual Review of Clinical Psychololgy. 2005;1:355–380. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viding E, Frick PJ, Plomin R. Aetiology of the relationship between callous unemotional traits and conduct problems in childhood. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;190 Suppl. 49:s33–s38. doi: 10.1192/bjp.190.5.s33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt EA, Donnellan MB, Blonigen DM, Krueger RF, Conger RD. Assessment of fearless dominance and impulsive antisociality via normal personality measures: Convergent validity, criterion validity, and developmental change. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2009;91:265–276. doi: 10.1080/00223890902794317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]