Abstract

Background and Objectives

The diverse US population requires medical cultural competency education for health providers throughout their pre-professional and professional years. We present a curriculum to train pre-health professional undergraduates by combining classroom education in the humanities and cross-cultural communication skills with volunteer clinical experiences at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) hospital.

Methods

The course was open to a maximum of 15 UCLA junior and senior undergraduate students with a pre-health or humanities major and was held in the spring quarters of 2002–2004. The change in students' knowledge of cultural competency was evaluated using the Provider's Guide to Quality and Culture Quiz (QCQ) and through students' written assignments and evaluations.

Results

Trainees displayed a statistically significant improvement in scores on the QCQ. Participants' written assignments and subjective evaluations confirmed an improvement in awareness and a high motivation to continue learning at the graduate level.

Conclusions

This is the first evaluated undergraduate curriculum that integrates interdisciplinary cultural competency training with patient volunteering in the medical field. The didactic, volunteering, and writing components of the course comprise a broadly applicable tool for training future health care providers at other institutions.

An increasingly diverse patient population requires that medical cultural competency be an integral part of the training for health care workers.1–8 As an example of the diverse US population, the 2000 US Census indicated that 30.9% of US citizens belong to a racial or ethnic minority group.9 By 2050, the US population is projected to exceed 394 million people, with nearly 90% of the growth from minority populations.10,11 The diversity of the population challenges medical providers to care for patients whose primary language and culture differ from those of the provider. Failure to provide culturally appropriate care can lead to patient dissatisfaction, poor adherence, and adverse health outcomes.4,12–20 In addition, lack of empathy for a patient's cultural values can result in stereotyping and biased treatment by a provider.4,21–23

Cultural competency training is primarily offered at the medical school, residency, and post-residency levels.24–26 Existing curricula for this training incorporate language training, interactive workshops, and adjunct clinical experiences in foreign countries or in North American regions with majority ethnic populations5,6,8,27–31 Discussions about ethical and cultural traditions related to health beliefs improve students' understanding of the patient's outlook on health care.5,6,8,24,27 Another component in current professional graduate education is the use of the humanities—such as art and literature—to foster cultural competency.24–26

Despite existing curricula, as described above, cultural competency training for college students interested in health careers is scarce and lacks in formal evaluation methods.32,33 Such instruction for pre-health professionals is attractive for multiple reasons. First, early exposure raises awareness about the importance of providing culturally sensitive patient care. Second, students learn early in their education how to interact with patients in a culturally appropriate way, which facilitates future unbiased interactions. Third, teaching undergraduate, pre-health professional students allows education of all future members of the health care team, including nurses, pharmacists, therapists, and physicians.

Here we describe an innovative cultural competency curriculum for undergraduate college students based on didactic discussions in the humanities integrated with volunteer clinical service. Students learned culturally appropriate communication methods with patients through lectures on literature, art, religion, and medicine. Students then applied these newly learned communication skills by interacting with hospitalized patients.

Methods

The curriculum for the Cultural Aspects of Medicine course was designed to increase awareness of cultural differences in health beliefs and practices among college students interested in health care-related professions. The objectives of the curriculum were threefold: (1) to train students in clinical cultural competency, (2) to teach cross-cultural communication skills, and (3) to provide practice through volunteer clinical opportunities. The course was open to all junior and senior undergraduate students enrolled at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). The only pre-requisite for the course was a pre-health or humanities declaration of major. The course was offered annually with a maximum enrollment of 15 students.

Course Instructors

All course directors had medical and cultural competency training and direct experience in primary patient care and patient interpreting. Course directors included an assistant clinical professor in family medicine; an MD/PhD student; and an assistant professor in pediatrics. A fourth course instructor was responsible for development of the medical communication training module as the director of Patient Affairs and Volunteer Services. This instructor also oversaw student volunteering and visiting at the UCLA Medical Center. The students interacted with course directors during each weekly seminar and during scheduled office hours weekly.

Course Structure

The 4-hour weekly seminar was primarily taught by three course directors with contributions from expert guest speakers. Each session was divided between a lecture and a small-group discussion (Table 1). In addition to weekly seminars, students volunteered 2–3 hours per week visiting patients. The purpose of these interactions was to give the students a chance to practice talking to patients from different cultures and ask patients about their health care beliefs, look for nonverbal cues, and to learn the patients' perspective as they interact with the health care system. Students who were multilingual and passed interpreter tests were also able to act as medical interpreters for the medical team. This latter interaction was entirely voluntary and not required for the course. Patient visits also allowed students to apply and practice skills learned in the weekly seminars.

Table 1.

Lecture Topics from the Course Syllabus

| Course Meeting | Lecture Topic |

|---|---|

| 1 | Course Introduction and Overview of Major Cultural Beliefs |

| Small-group Discussion/Role Playing/Communication Workshop | |

| 2 | Communicating With Hospital Patients |

| Small-group Discussion/Role Playing/Communication Workshop | |

| 3 | Exploring Inequity in Health Care |

| Small-group Discussion/Role Playing/Communication Workshop | |

| 4 | Faith Panel: Role of Religion in Health Care |

| Small-group Discussion/Role Playing/Communication Workshop | |

| 5 | Cultural Aspects of the Grieving Process |

| Small-group Discussion/Role Playing/Communication Workshop | |

| 6 | Music and Healing in Medicine: Examples From the Native American Culture |

| Small-group Discussion/Role Playing/Communication Workshop | |

| 7 | Traditional Medicine Beliefs and Practices Cross Culturally With Ethnographic Examples From Mexico and Latin America |

| Small-group Discussion/Role Playing/Communication Workshop | |

| 8 | The Effect of the Holocaust and Other Global Conflicts on the Health of Future Generations |

| Small-group Discussion/Role Playing/Communication Workshop | |

| 9 | Art as a Form of Communication in Healing |

| Small-group Discussion/Role Playing/Communication Workshop | |

| 10 | Cultural Perspectives From Health Care Professionals: Doctors, Nurses, Social Workers |

| Student Final Project Presentations |

Course Content

Introduction

The first lecture of the course was an overview of major cultural beliefs, and it was followed by a discussion on clinical cultural competency and its relationship to inequity in health care. The purpose was to introduce students to different cultural beliefs, to discuss specific differences in health outcomes for different populations, and to define cultural competency. Students also learned the difference between generalizing and stereotyping and how to elicit the individual patient's cultural beliefs. After the lecture, the students participated in a role-playing game where they adopted practices of two different cultures that were forced to interact to achieve a common goal. The game allowed students to understand the types of communication conflicts that can arise in cross-cultural interactions. This lecture was given by a guest speaker with extensive expertise in cultural competency.

Medical Communication

In this seminar, UCLA Patient Affairs liaisons taught students how to start a conversation, listen actively, and end a clinical encounter. Students learned about nonverbal communication and how patients' body language offers clues about their attitude toward the provider and Western medicine. For example, a role-playing exercise among students demonstrated how gender roles could be important for patients with different cultural beliefs. Students discussed a case of a female patient from a Middle Eastern background who avoided eye contact with a male provider. This exercise showed students that a patient's behavior might have a cultural explanation.

Role of Religion in Health Care Encounters

This seminar was taught by a panel with representatives from the Christian, Jewish, Muslim, and Buddhist faiths. Each representative gave an introduction of their religion and provided examples of beliefs a patient of their faith may hold in a medical setting. Students learned that a patient's religious beliefs influence medical decisions and influence interaction with the medical team. For example, a critically ill patient from a Buddhist tradition may need religious leaders and multiple family members at the bedside. Although this request may violate hospital policy on the number of allowed visitors, honoring such beliefs would be critical for a patient's comfort.

Cultural Aspects of Grieving

This seminar focused on understanding cultural differences in end-of-life care and on exposing students to the role of community-based organizations in support of terminally ill patients and their families. Students visited a community bereavement center where they interacted with individuals who experienced medical treatment of a terminally ill family member. They learned the importance of honest communication among the medical team, the patient, and the patient's family, including (1) listening to the individual needs of the patient, (2) incorporating the family's needs, and (3) being open to alternative methods of treatment without endangering the patient. Students also learned how these experiences might differ depending on the patient's culture.

Art and Music as Forms of Communication in Healing

Lectures on art and music focused on experiences and beliefs of patients from minority groups and of patients who have survived concentration/isolation camps, natural and manmade disasters, forced immigration, ethnic cleansing, and being victims of violence in areas of conflict. By viewing artwork and listening to music of different groups, students analyzed how critical life experiences and exposure to a global conflict lead to acute and chronic medical conditions. Students also learned how to interpret a patient's history with increased social awareness.

Cultural Perspectives From Health Care Professionals

This seminar allowed students to interact with a panel of medical providers comprised of nurses, resident training physicians, and faculty physicians. Medical providers shared examples of how understanding the patients' culture allowed them to improve patient care. For example, a diabetic patient from a Hispanic background may have difficulty adjusting to a low-fat diet due to many of their culturally accepted foods having a higher fat content. In this case, students learned how the provider can discuss which foods are most essential to the patient and which foods can be exchanged for a low-fat alternative.

Cultural Competency Through Literature

Ann Fadiman's The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down was the main text for the course. Examples of cultural clashes illustrated in the book between providers and the Hmong family provoked classroom discussion of factors that lead to cross-cultural misunderstandings in a medical setting and how to resolve such conflicts appropriately. Students also read articles on health care disparities and the patient–doctor relationship.34–36

Hospital Volunteering

Students completed at least 20 hours of hospital volunteering by visiting patients. During visits, students discussed how the patient's cultural background influenced their experiences in the hospital. They were also able to practice the communication skills learned in class, such as nonverbal cues, opening and ending a conversation, and understanding how patients' cultures may change the patient's perception of the medical environment. This exposure allowed students to witness patient-provider interaction at all levels of the health provider team. Examples of successful and unsuccessful communication skills were then discussed in the weekly seminars. Students with a second language who wished to also serve as interpreters were trained in medical interpreting through the UCLA Patient Affairs Department and interpreted in a provider-patient context in Tagalog, Mandarin Chinese, Cantonese, Arabic, Spanish, Farsi, French, Vietnamese, Russian, and Italian.

Student Evaluation

Students were evaluated on class discussion (15%), final paper and presentation (45%), and on completion of volunteer hospital hours (40%). In weekly journals, students discussed how their hospital experiences integrated with the knowledge obtained from lectures and readings (Table 2). For the final paper, students selected a culture and analyzed how the beliefs of a patient from that culture influence the patient's medical experience as well as how a health care provider can contribute to a successful medical interaction.

Table 2.

A Student's Journal Entry Answering Arthur Kleinman's “Eight Questions”

| Arthur Kleinman's “Eight Questions” | A Korean Patient's Response | An American Patient's Response |

|---|---|---|

| 1. What do you call the problem? | I don't know. It seems that he/she loses control of her brain. It is a sort of a shock. | Epilepsy |

| 2. What do you think has caused the problem? | The mother was shocked or surprised during her pregnancy. | A structural or metabolic abnormality in neuronal firing. |

| 3. Why do you think it started when it did? | When the mother undergoes a shock during her pregnancy, it disturbs the baby's mental state. After birth, the baby will always be affected, and it will be noticed by other people. | There may have been a specific trigger which led to the development of seizures. |

| 4. What do you think the sickness does? How does it work? | It destabilizes a person's mental energies. | Epilepsy results in synchronous neuronal firing in the brain. |

| 5. How severe is the sickness? Will it have a short or long course? | I don't know. I expect my doctor to determine this. I am eager to know. | I don't know, but I am sure my doctor will tell me. I may also seek a second opinion from a tertiary hospital. |

| 6. What kind of treatment do you think the patient should receive? What are the most important results you hope he/she receives from this treatment? | She needs an herbal medicine, or a traditional mixture or potion. If the right medicines are taken, then her mind will be able to slowly come back to harmony. | We need to get the most up-to-date medications. The newest treatments will offer the most hope for controlling epilepsy. |

| 7. What are the chief problems the sickness has caused? | This problem worries the family and friends. In addition, other people may wonder what is happening. It doesn't look good. | Epileptic seizures have led to self injury and asphyxiation. It has also been stigmatizing. |

| 8. What do you fear most about the sickness? | We fear that our child will never have a normal life. | I am confident we will solve the problem. I just hope this disease is curable. |

* These questions are designed to elicit the patient's perspective on his/her illness and therefore help the provider become aware of important cultural perceptions.Students were asked to answer the eight questions for the American and non-American cultures based on readings, class discussions, and patient interactions.

Course Evaluation

Students were asked to take the Provider's Guide to Quality and Culture Quiz (QCQ) as one objective measure to evaluate the effectiveness of the course in teaching cultural competency. The QCQ is a 21-item multiple-choice and true/false questionnaire (Version 2002, created jointly by the Management Sciences for Health, US Department of Health and Human Services, US Health Resources and Services Administration, and Bureau of Primary Health Care).37 This questionnaire has been used to “reflect on one's experience, knowledge, and attitudes toward culturally diverse populations.”37 The questionnaire was chosen to assess students' prior knowledge of different cultures, common perceptions of health care practices by people from different cultures, and beliefs about the importance of culturally competent care. The UCLA Institutional Review Board approved administration of this test, and each student provided written, informed consent.

The course was taught during the spring quarters of the 2002, 2003, and 2004 academic years. A course facilitator administered the QCQ on the first (pre-QCQ) and last sessions (post-QCQ) of the course. To match student tests and maintain anonymity, students were asked to use a 6-digit identification code. Correct answers were assigned 1 point, and incorrect, missing, or unclearly marked answers were assigned no points.

Data Analysis

Student score distribution was analyzed for normality using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Student scores on the QCQ deviated significantly from normality (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, P<.03). Therefore, a nonparametric Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test was applied to assess the difference in median test scores between unpaired pre-QCQ and post-QCQ. Histograms and box and whisker plots show differences in score distributions and percentiles. All tests were performed using R-based programs (version 2.3) (www.R-project.org).

Results

The authors used the pre- and post-QCQ tests to assess student knowledge in cultural competency before and after taking the course. Twenty-seven students took the pre-QCQ, and 24 students took the post-QCQ (unpaired group). A total of 18 students took both the pretests and posttests (paired group). Fewer paired responses were due to enrollment after the pre-QCQ administration or students dropping out of the course before the post-QCQ. We combined responses for the three quarters during which the course was taught.

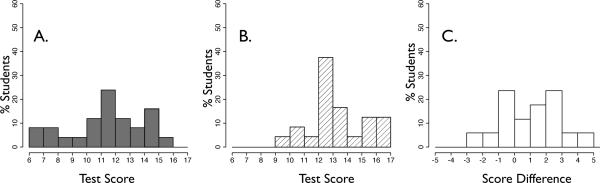

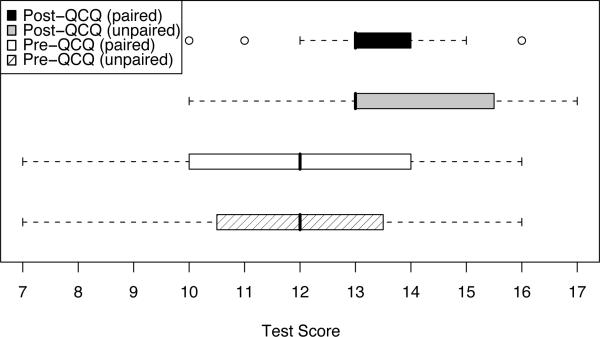

Post-QCQ scores were statistically significantly higher in both the paired and unpaired groups compared to the pre-QCQ (Wilcoxon Signed Rank test, P= .0034, Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test P= .0037, Figure 1A, B). The improvement was most pronounced for the 0th and 25th score percentiles for the pretests and posttests and the distribution of scores became tighter for the post-QCQ groups (Figure 2, Figure 1 A, B). In the paired group, 66.7% of students improved their score by 1–5 points, 22.2% did not have a change in score, and 11.1% performed worse by 1–3 points (Figure 1 C).

Figure 1.

Histograms of Student Scores on the Quality and Culture Quiz (QCQ)*

* There is a right shift in the direction of higher scores in the post-QCQ distribution compared to the pre-QCQ. 66.7% of students improved their score by 1–5 points, as shown in C.

A. Pre-QCQ scores, unpaired group. B. Post-QCQ scores, unpaired group. C. Score difference (post-pre), paired group.

Figure 2.

Box-and-Whisker Plot of Student Scores on the Pre- and Post-Quality and Culture Quiz (QCQ)*

The plot shows the range (scores between tick marks), 25th% (left-most border of colored blocks), 50th% (dark vertical line on colored blocks), 75th% (rightmost border of colored blocks), circles are judged to be outliers by standard criteria (1.5× interquantile range method).

Students also completed subjective comments about their learning experiences (Table 3), reporting that the course had high value in their overall undergraduate education. Students stated that they had high interest in continuing to learn about cultural competency in future postgraduate training and that they expected to apply the knowledge in real life. Course directors' evaluation of student journals and final projects provided further evidence that students gained deeper appreciation for the cultural ramifications of clinical interactions.

Table 3.

Sample of Student Subjective Comments About the Course

| “Thank you for the class. I stumbled onto it by chance, and I've been telling everyone about it ever since. It's one of the classes that I've taken at UCLA in my 4 years that I know I will put the knowledge to use in the future.”—CN |

| “Thank you so much for organizing a very interesting class. I loved it. This class is one of the best classes I've ever taken.”—RI |

| “I really enjoyed this class. I learned a lot of useful information, and I know I will be applying it to real life unlike many other classes that I take, where the information comes in and out. This is sad but it's the truth. However, learning about being culturally sensitive as health care providers is something I've never thought about and have taken for granted. Thanks to this class, I am much more aware of the problem.”—NT |

| “I really enjoyed the class and I definitely learned how to be a better future physician.”—KT |

| “Thanks again for a great class. I am really looking forward to applying the skills I learned in the class to my hospital interactions in the future.”—JR |

Discussion

The course objective was to embark undergraduate students on a lifelong development of critical skills as future providers of culturally competent health care. Through interactive class presentations, discussions, and written assignments, students were taught proper ways to communicate with patients from different cultures and ways to reduce cross-cultural conflicts in a hospital setting. Students also exercised multiple opportunities to apply skills learned in the course through cross-cultural patient interactions.

Quantitative evaluation of the curriculum illustrated that students significantly improved in cultural competency knowledge. QCQ Score assessment suggested that students who entered the class with cultural competency skills improved their skills further. Students lacking cross-cultural skills before enrollment became more culturally competent after the course. We acknowledge that the QCQ is not the sole, or perhaps even the best, measure of students' proficiency in cultural competency. Yet, a significant improvement in scores on the posttest—together with student course evaluations and course directors' evaluation of student journals and final projects—suggest that our curriculum exerted significant, positive effects on the students.

Current health care training emphasizes students' mastery of basic and clinical sciences. However, medicine is as much subjective art as objective science, and effective clinical communication skills are requisite to best clinical practices. We propose that starting cultural competency training at an undergraduate college level is optimal given the fertile learning experiences at this stage and the receptiveness of younger learners. Offering a medical cultural competency course along with accepted pre-health professional courses emphasizes the importance of the subject. Undergraduate education also exposes students across all the health professions. Even for students who do not become culturally competent from undergraduate experiences, early exposure increases awareness and helps to cope better with future challenges in training and practice.

Our study design was limited by the convenient availability of experts, small budget (under $1,000), short curricular time to encompass all cultural themes, and lack of validated tools to evaluate cultural competence, at the time of our study (2002). In future iterations of this course, the instructors wish to include expertise from other religions (eg, animistic Hindu and Wiccan traditions) and to extend coverage to humanitarian disasters (eg, the Trail of Tears, the Armenian genocide, and ethnic cleansing in the former Yugoslavia). It is clear that one individual cannot adequately represent the rich variations within a distinct tradition (comparing, say, Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant Christians). We also emphasize to readers the need to structure the volunteering activities under certified interpreters, not only to enhance training but also to reduce potential medical-legal risk. Despite its initial weaknesses, this novel curriculum in cultural competency for undergraduates improved students' cultural competency prior to formal clinical training. General acceptance of definitions for cultural competencies, specific outcome measures, and larger learner sample size would greatly assist future research in this field.

Conclusions

The presented curriculum integrates the humanities (art, literature, religion, and music) and practical experiences to motivate students to attain cultural competency. The writing components and volunteering aspect of the course comprise universal, cost-effective tools for training providers who are challenged by cross-cultural conflicts in health care training and delivery. This curriculum can be applied to train undergraduate pre-health professional students at institutions with diverse patient and student populations.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the UCLA Office of Instructional Development (to EM, LW, RF), NIH Grants T32 GM08042 and DC00217 (to EM), K08 DK02876, and the SPC Russell H. Nahvi Memorial Fund for Pediatric Research at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio (to RF).

The authors thank their students and the staff at the Departments of Patient Affairs, Interpreter Services and Volunteer Services for outstanding support throughout the project; the Department of Family Medicine and Patrick Dowling, MD, for administrative support; Paula Henderson, MD, for assistance with teaching the course; Beserat Hagos and Patricia Anaya for help with course logistics and scheduling; Caleb Ho, Junko Obayashi, and Anna Avik for help administering the QCQ; and the guest lecturers whose participation made this project possible. The authors also extend gratitude to Our House (Los Angeles) for supporting this work by hosting students alongside bereavement counselors and families. The authors thank Gloria Matthews, Nora Eblen, and Debra Tate for superb administrative assistance at the Division of Pediatric Endocrinology at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

References

- 1.Beagan BL. Teaching social and cultural awareness to medical students: “it's all very nice to talk about it in theory, but ultimately it makes no difference.”. Acad Med. 2003;78(6):605–14. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200306000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flores G, Gee D, Kastner B. The teaching of cultural issues in US and Canadian medical schools. Acad Med. 2000;75(5):451–5. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200005000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kagawa-Singer M, Kassim-Lakha S. A strategy to reduce cross-cultural miscommunication and increase the likelihood of improving health outcomes. Acad Med. 2003;78(6):577–87. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200306000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Betancourt JR. Cross-cultural medical education: conceptual approaches and frameworks for evaluation. Acad Med. 2003;78(6):560–9. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200306000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Champaneria MC, Axtell S. Cultural competence training in US medical schools. JAMA. 2004;291(17):2142. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.17.2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crandall SJ, George G, Marion GS, Davis S. Applying theory to the design of cultural competency training for medical students: a case study. Acad Med. 2003;78(6):588–94. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200306000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Humphris GM, Kaney S. Assessing the development of communication skills in undergraduate medical students. Med Educ. 2001;35(3):225–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Godkin MA, Savageau JA. The effect of a global multiculturalism track on cultural competence of preclinical medical students. Fam Med. 2001;33(3):178–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.2000 Census: racial, ethnic minority populations surge. www.facts.com/2001213270.htm.

- 10.Census Bureau releases data on people who chose more than one race. Public Health Rep. 2001;116:626–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Census Bureau Dynamic diversity: projected changes in US race and ethnic composition 1995 to 2050. http://www.mbda.gov/?section_id=6&bucket_id=16&content_id=3195&well=entire_page.

- 12.Stewart M, Brown JB, Boon H, Galajda J, Meredith L, Sangster M. Evidence on patient-doctor communication. Cancer Prev Control. 1999;3(1):25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morales LS, Cunningham WE, Brown JA, Liu H, Hays RD. Are Latinos less satisfied with communication by health care providers? J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(7):409–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.06198.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Gonzales JJ, et al. Race, gender, and partnership in the patient-physician relationship. JAMA. 1999;282(6):583–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.6.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langer N. Culturally competent professionals in therapeutic alliances enhance patient compliance. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1999;10(1):19–26. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Betancourt JR. Cultural competency: providing quality care to diverse populations. Consult Pharm. 2006;21(12):988–95. doi: 10.4140/tcp.n.2006.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Breier-Mackie S. Cultural competence and patient advocacy: the new challenge for nurses. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2007;30(2):120–2. doi: 10.1097/01.SGA.0000267933.36748.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munoz CC. Cultural concepts to consider in the care of the ethnically diverse client and family. Ohio Nurses Rev. 2001;76(3):12–8. quiz 18–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Connell MB, Korner EJ, Rickles NM, Sias JJ. Cultural competence in health care and its implications for pharmacy. Part 1. Overview of key concepts in multicultural health care. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27(7):1062–79. doi: 10.1592/phco.27.7.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Racher FE, Annis RC. Respecting culture and honoring diversity in community practice. Res Theory Nurs Pract. 2007;21(4):255–70. doi: 10.1891/088971807782427985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schulman KA, Berlin JA, Harless W, et al. The effect of race and sex on physicians' recommendations for cardiac catheterization. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(8):618–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902253400806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Ryn M, Burke J. The effect of patient race and socioeconomic status on physicians' perceptions of patients. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50(6):813–28. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00338-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Donini-Lenhoff FG, Hedrick HL. Increasing awareness and implementation of cultural competence principles in health professions education. J Allied Health. 2000;29(4):241–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yacoub AA, Ajeel NA. Teaching medical ethics in Basra: perspective of students and graduates. East Mediterr Health J. 2000;6(4):687–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bleakley A, Marshall R, Bromer R. Toward an aesthetic medicine: developing a core medical humanities undergraduate curriculum. J Med Humanit. 2006;27(4):197–213. doi: 10.1007/s10912-006-9018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spiro H. What is empathy and can it be taught? Ann Intern Med. 1992;116(10):843–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-116-10-843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gonzalez-Lee T, Simon HJ. Teaching Spanish and cross-cultural sensitivity to medical students. West J Med. 1987;146(4):502–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rubenstein HL, O'Connor BB, Nieman LZ, Gracely EJ. Introducing students to the role of folk and popular health belief systems in patient care. Acad Med. 1992;67(9):566–8. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199209000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McGarry K, Clarke J, Cyr MG. Enhancing residents' cultural competence through a lesbian and gay health curriculum. Acad Med. 2000;75(5):515. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200005000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brainin-Rodriquez JE. A course about culture and gender in the clinical setting for third-year students. Acad Med. 2001;76(5):512–3. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200105000-00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mao C, Bullock CS, Harway EC, Khalsa SK. A workshop on ethnic and cultural awareness for second-year students. J Med Educ. 1988;63(8):624–8. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198808000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fried C, Madar S, Donley C. The biomedical humanities program: merging humanities and science in a premedical curriculum at Hiram College. Acad Med. 2003;78(10):993–6. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200310000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ellison NM, Radecke MW. An undergraduate course on palliative medicine and end-of-life issues. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(2):354–62. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Galanti G-A. Caring for patients from different cultures. third edition University of Pennsylvania Press; Philadelphia: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nelson A. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002;94(8):666–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fadiman A. The spirit catches you and you fall down: a Hmong child, her American doctors, and the collision of two cultures. first edition Farrar, Straus, and Giroux; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 37.The provider's guide to quality and culture. http://erc.msh.org/mainpage.cfm?file=1.0.htm&module=provider&language=English.