Abstract

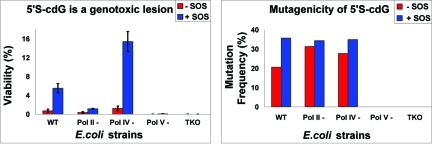

8,5′-Cyclopurines, making up an important class of ionizing radiation-induced tandem DNA damage, are repaired only by nucleotide excision repair (NER). They accumulate in NER-impaired cells, as in Cockayne syndrome group B and certain Xeroderma Pigmentosum patients. A plasmid containing (5′S)-8,5′-cyclo-2′-deoxyguanosine (S-cdG) was replicated in Escherichia coli with specific DNA polymerase knockouts. Viability was <1% in the wild-type strain, which increased to 5.5% with SOS. Viability decreased further in a pol II– strain, whereas it increased considerably in a pol IV– strain. Remarkably, no progeny was recovered from a pol V– strain, indicating that pol V is absolutely required for bypassing S-cdG. Progeny analyses indicated that S-cdG is significantly mutagenic, inducing ∼34% mutation with SOS. Most mutations were S-cdG → A mutations, though S-cdG → T mutation and deletion of 5′C also occurred. Incisions of purified UvrABC nuclease on S-cdG, S-cdA, and C8-dG-AP on a duplex 51-mer showed that the incision rates are C8-dG-AP > S-cdA > S-cdG. In summary, S-cdG is a major block to DNA replication, highly mutagenic, and repaired slowly in E. coli.

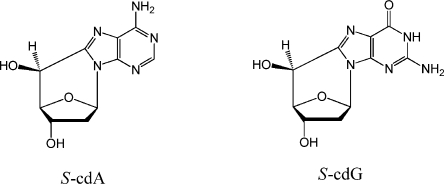

The tandem DNA lesions, 8,5′-cyclopurine 2′-deoxynucleosides (cPDNs), formed by ionizing radiation and other processes that generate reactive oxygen species, are unique in that they contain damage to both the purine base and the 2′-deoxyribose sugar.(1) These lesions exist as 5′R and 5′S diastereomers and have been detected in vitro and in vivo in DNA derived from a diverse array of cells and organisms2,3 (Scheme 1 shows the structures of S-cdA and S-cdG). Although these lesions were discovered in the 1960s,(4) interest in them was revived in 2000 because of reports that in mammalian cells 8,5′-cyclo-2′-deoxyadenosine (cdA) diastereomers are repaired by nucleotide excision repair (NER), and not by the base excision repair enzymes.5,6R-cdA is more efficiently repaired than S-cdA.(6) The cPDNs have been thought to play a role in neurologic diseases in certain Xeroderma Pigmentosum patients with defects in NER.(7) It was also shown that S-cdA accumulates in vivo in genomic DNA of csb–/– mice, suggesting that this lesion may accumulate in Cockayne syndrome patients.(8) A recent study provided evidence of the involvement of the DNA repair enzyme NEIL1 in NER of R-cdA and S-cdA, although the mechanism remains unclear.(9)S-cdA has been reported to be a strong block of gene expression in CHO and human cells.(5) It prevents the binding of TATA binding protein and strongly reduces the level of transcription in vivo.(10) Both R-cdA and S-cdA block the elongation of a primer by mammalian DNA pol δ and T7 DNA polymerase.(6) In vitro translesion synthesis (TLS) studies established that mammalian DNA polymerase η can bypass R-cdA but not S-cdA.(11) Most of the studies of cyclopurines to date have focused on cdA, and relatively little is known about the effects of the cdG diastereomers, except a preliminary in vitro study showed that S-cdG does not block the primer elongation by the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I and dAMP is preferentially incorporated opposite it.(12)

Scheme 1. Structures of S-cdA and S-cdG.

To determine the replication properties of S-cdG, we have constructed a single-strand plasmid containing a single S-cdG in a CG*T sequence, which was replicated in several isogenic strains of Escherichia coli with specific DNA polymerase knockouts. A comparison of the number of colony-forming units obtained per microgram of the S-cdG construct following replication in E. coli relative to the control (i.e., construct containing dG) provided the viability, presumably reflecting also the lesion bypass efficiency.

As shown in Table 1, the viability of cdG decreased to 0.7% in E. coli cells with normal repair and replication functions. With SOS induction, viability increased ∼8-fold to 5.5%. This is surprising in view of the fact that this level of toxicity has been observed with highly genotoxic lesions such as abasic sites,(13) which, unlike cdG, lack the ability to form Watson–Crick hydrogen bonds with an incoming nucleotide. In the E. coli strain deficient in pol II, viability was even lower (at 0.35%), which increased ∼3-fold (to 1.15%) with SOS. More striking was the fact that no progeny could be recovered from the pol V-deficient strain. This suggests that pol V (UmuD′2C) is indispensable for bypassing S-cdG, and pol II may play a secondary role but is unable to bypass the lesion independently. The absolute requirement of pol V was also reflected in the strain that lacks pol II, pol IV, and pol V, the three SOS polymerases in E. coli, in which no progeny could be detected. By contrast, in a pol IV-deficient strain, viability increased to 1.2 and 15.4% without and with SOS, respectively. The increase in viability in the pol IV-deficient strain can be explained if one considers that when both polymerases are present in a cell, pol IV competes with pol V to conduct TLS but the attempt is futile because pol IV may not be able to bypass the lesion. Therefore, in the absence of pol IV, pol V is able to conduct TLS of significantly more S-cdG sites, thus enhancing the viability in a pol IV-deficient strain. This is more prominent with SOS, when many more copies of pol V are present. A competition between pol IV and pol V was postulated in the bypass of G[8,5-Me]T, another form of γ-radiation-induced DNA damage, except both polymerases can bypass this lesion and cause different types of mutations.(14) Competition among DNA polymerases have been documented in other cases as well (e.g., ref (15)). An alternative, but not mutually exclusive, rationale is that UmuD2 and RecA act in concert to modulate DinB,(16) which may reduce the number of active pol V molecules. In fact, the expression level of chromosomal DinB is 6–12 times higher than that of UmuC with ∼2500 molecules of DinB in an SOS-induced cell.(17) Therefore, we hypothesize that in the pol IV-deficient (ΔdinB) strain, many additional molecules of pol V are available for TLS of S-cdG, because UmuD2 is not needed to modulate DinB.

Table 1. Viability of S-cdG in E. colia.

| polymerase knocked out | without SOS | with SOSb |

|---|---|---|

| none | 0.69 ± 0.36 | 5.50 ± 0.99 |

| pol II | 0.35 ± 0.17 | 1.15 ± 0.07 |

| pol IV | 1.22 ± 0.50 | 15.4 ± 2.1 |

| pol V | <0.001 | <0.05 |

| pol II/pol IV/pol V | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Viability was determined by comparing the transformation efficiency of the S-cdG plasmid with that of the control construct. The data represent four independent experiments.

SOS was induced with 20 J/m2 UV irradiation.

To determine the frequency of error in TLS of S-cdG, we analyzed the progeny plasmid by oligonucleotide hybridization followed by DNA sequencing. In the wild-type strain, without SOS, 79% progeny contained a G at the cdG site, indicating correct read-through by a DNA polymerase, whereas 21% showed cdG → A mutations (Table 2). With SOS, the mutation frequency (MF) increased to ∼36%, of which most (34.4%) contained cdG → A transitions and only ∼1% had deletion of the C immediately 5′ to cdG. In uninduced cells, the MF values were 31 and 27% in pol II-deficient and pol IV-deficient strains, respectively. While in uninduced cells the MF varied to some extent, in SOS-induced cells it remained approximately the same in the different strains (Table 2). A low frequency (0.6%) of cdG → T mutations was also observed in the pol IV-deficient strain (Table 2). If pol V is the only polymerase that can conduct TLS of S-cdG, MF in SOS-induced cells, regardless of their proficiency or deficiency in other polymerases, is unlikely to have an effect, as noted here. However, in the uninduced state, the mechanism of TLS by pol V may be more complex, because of the availability of only a limited amount of this protein. Indeed, uninduced and SOS-induced E. coli cells provide a distinct pattern of TLS of the abasic site.(18)

Table 2. Mutations Induced by S-cdG in E. coli.

| polymerase knocked out | SOSa | expt. no. | no. of colonies screened | no. of mutationsb (%) | no. of G → A mutations (%) | no. of other mutations (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| none | without | 1 | 42 | 8 | 8 | 0 |

| 2 | 26 | 6 | 6 | 0 | ||

| total | 68 | 14 (20.6) | 14 (20.6) | 0 | ||

| with | 1 | 86 | 31 | 30 | 1c | |

| 2 | 71 | 25 | 24 | 1c | ||

| total | 157 | 56 (35.7) | 54 (34.4) | 2 (1.3) | ||

| pol II | without | 1 | 37 | 12 | 12 | 0 |

| 2 | 46 | 14 | 14 | 0 | ||

| total | 83 | 26 (31.3) | 26 (31.3) | 0 | ||

| with | 1 | 61 | 21 | 20 | 1c | |

| 2 | 67 | 23 | 23 | 0 | ||

| total | 128 | 44 (34.4) | 43 (33.6) | 1 (0.8) | ||

| pol IV | without | 1 | 85 | 23 | 22 | 1c |

| 2 | 70 | 20 | 19 | 1d | ||

| total | 155 | 43 (27.7) | 41 (26.5) | 2 (1.3) | ||

| with | 1 | 246 | 85 | 83 | 2d | |

| 2 | 81 | 29 | 29 | 0 | ||

| total | 327 | 114 (34.9) | 112 (34.3) | 2 (0.6) |

SOS was induced with 20 J/m2 UV irradiation.

For each strain, the mutation frequency of the control construct was <1% (data not shown).

5′-C deletion.

G → T mutation.

A consequence of the covalent bond between C8 of guanine and C5′ of 2′-deoxyribose is that the N-glycosidic torsion angle of guanine is locked in the anti domain. Therefore, the incoming dCMP can form a nearly normal Watson–Crick base pair, whereas an incoming dTMP is capable of forming a slightly distorted wobble pair. Both outcomes have been noted in the pol V-dependent TLS. The high toxicity of the lesion implies, however, that most DNA polymerases have difficulty in bypassing a locked nucleotide, presumably because the accommodation at the active site of the polymerase likely involves rotational adjustments of the nucleoside around the N-glycosidic bond.

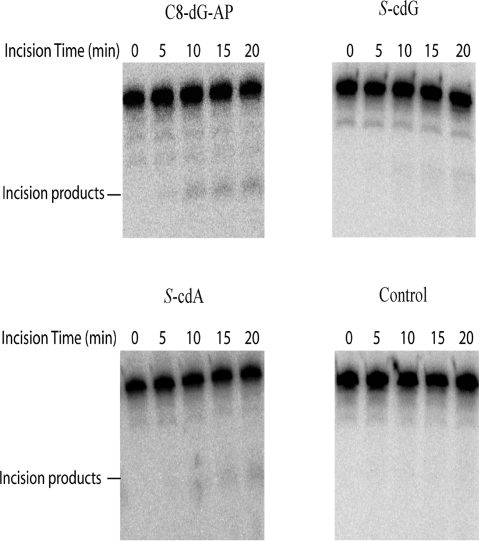

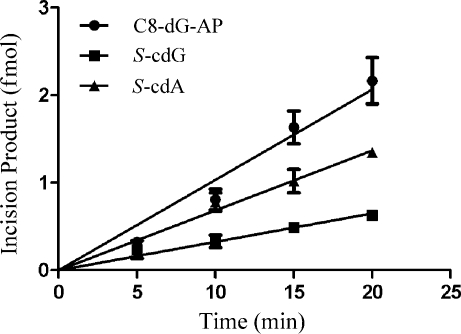

In view of the NER of cPDNs in mammalian cells, we also wanted to determine how efficiently these types of damage are repaired by UvrABC, the core NER proteins of E. coli.(19) In the same local sequence we used for constructing the S-cdG plasmid, 51-mer duplex oligonucleotides containing S-cdG, S-cdA, and C8-dG-AP, the C8-dG adduct formed by 1-nitropyrene, were prepared, and the substrates were subjected to UvrABC incision reactions. As shown in Figure 1, the S-cdG, S-cdA, and C8-dG-AP substrates were incised by UvrABC nuclease in a kinetic assay. These substrates were radioactively labeled at the 5′-end of the lesion-containing strand, and the major incision products were observed as a 17-nucleotide fragment by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis under denaturing conditions. Quantitative analysis of the incision data is shown in Figure 2. The data indicated that the substrates were incised at differing efficiencies depending on the type of lesion. S-cdG was incised at a 2-fold slower rate than S-cdA, which, in turn, was incised at a rate that was 70% of that of C8-dG-AP. The results are summarized in Table 3. In an earlier study, we determined that C8-dG-AP is incised by UvrABC at a rate that is 40% of that of the bulky adduct C8-dG-AAF (the C8-dG adduct of N-acetyl-2-aminofluorene), which is considered a good substrate for UvrABC.(20)

Figure 1.

Incisions of 51-mers containing C8-dG-AP (top left), S-cdG (top right), S-cdA (bottom left), and control (or no damage) (bottom right). The lesion-containing and control strands were 5′-terminally labeled with 32P. The DNA substrates were incubated with UvrABC proteins in UvrABC buffer in the presence of 1 mM ATP at 37 °C for the indicated periods. The reaction products were analyzed via 12% urea–PAGE under denaturing conditions.

Figure 2.

Kinetics of UvrABC incisions of substrates containing C8-dG-AP (●), S-cdG (◼), and S-cdA (▲).

Table 3. Incision Rates of DNA Lesions.

| incision rate (fmol/min) | |

|---|---|

| C8-dG-AP | 0.103 ± 0.006 |

| S-cdA | 0.068 ± 0.003 |

| S-cdG | 0.032 ± 0.002 |

Consequently, relative to C8-dG-AAF, S-cdG was incised 1 order of magnitude less efficiently. Furthermore, while both the cPDNs may be considered inefficient substrates for UvrABC, S-cdG was incised less than half as efficiently as S-cdA.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to M. Moriya (State University of New York, Stony Brook, NY) for the pMS2 plasmid and G. Walker (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA) for the E. coli strains.

Supporting Information Available

Materials and detailed experimental procedures. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

This work was supported by National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Grant ES013324 to A.K.B. and National Cancer Institute Grant CA86927 to Y.Z.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Chatgilialoglu C.; Ferreri C.; Terzidis M. A. (2011) Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 1368–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaruga P.; Birincioglu M.; Rodriguez H.; Dizdaroglu M. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 3703–3711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaruga P.; Dizdaroglu M. (2008) DNA Repair 7, 1413–1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keck K. (1968) Z. Naturforsch., B 23, 1034–1043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks P. J.; Wise D. S.; Berry D. A.; Kosmoski J. V.; Smerdon M. J.; Somers R. L.; Mackie H.; Spoonde A. Y.; Ackerman E. J.; Coleman K.; Tarone R. E.; Robbins J. H. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 22355–22362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuraoka I.; Bender C.; Romieu A.; Cadet J.; Wood R. D.; Lindahl T. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 3832–3837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks P. J. (2008) DNA Repair 7, 1168–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkali G.; de Souza-Pinto N. C.; Jaruga P.; Bohr V. A.; Dizdaroglu M. (2009) DNA Repair 8, 274–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaruga P.; Xiao Y.; Vartanian V.; Lloyd R. S.; Dizdaroglu M. (2010) Biochemistry 49, 1053–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marietta C.; Gulam H.; Brooks P. J. (2002) DNA Repair 1, 967–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuraoka I.; Robins P.; Masutani C.; Hanaoka F.; Gasparutto D.; Cadet J.; Wood R. D.; Lindahl T. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 49283–49288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasparutto D.; Bourdat A. G.; D’Ham C.; Duarte V.; Romieu A.; Cadet J. (2000) Biochimie 82, 19–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence C. W.; Borden A.; Banerjee S. K.; LeClerc J. E. (1990) Nucleic Acids Res. 18, 2153–2157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raychaudhury P.; Basu A. K. (2011) Biochemistry 50, 2330–2338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings P. J.; Hersh M. N.; Thornton P. C.; Fonville N. C.; Slack A.; Frisch R. L.; Ray M. P.; Harris R. S.; Leal S. M.; Rosenberg S. M. (2010) PLoS One 5, e10862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godoy V. G.; Jarosz D. F.; Simon S. M.; Abyzov A.; Ilyin V.; Walker G. C. (2007) Mol. Cell 28, 1058–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. R.; Matsui K.; Yamada M.; Gruz P.; Nohmi T. (2001) Mol. Genet. Genomics 266, 207–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroeger K. M.; Goodman M. F.; Greenberg M. M. (2004) Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 5480–5485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancar A.; Rupp W. D. (1983) Cell 33, 249–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo C.; Krishnasamy R.; Basu A. K.; Zou Y. (2000) Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 3719–3724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.