Abstract

Hereditary multiple exostosis (HME) is a benign condition with multiple bony tumors with cartilage caps (osteochondromas), mainly presenting in the long and flat bones. Usually the presentation for HME is between 2 and 10 years of age and most are seen by 4 years of age (Khan et al. 2009). In this paper, we report a family with three members (father, son, and a daughter) who had very early presentations of HME in the fingers within the first 2 years of age. The son presented with bony nodules at 7 months of age, and he required surgery at 13 months of age for a severe functional deformity of his left ring finger. He also had an unusual histological presentation on his osteochondroma that consists of only subperiosteal cartilage without ossification.

Keywords: Hand, Hereditary multiple exostoses, Osteochondroma, Early presentation

Introduction

Hereditary Multiple Exostoses

Epidemiology

Exostoses are the most frequent benign bone tumors, which accounts for 20–50% of benign bone tumors and 10–15% of both benign and malignant bone tumors [29, 39]. Exostosis is characterized by hyaline cartilage caps and is found usually at the metaphysis of long and flat bones such as the femur, tibia, fibula, and humerus. It can affect the longitudinal growth of the bones during development [22, 51].

Hereditary multiple exostosis (HME) is a multi-phenotypic autosomal dominant disorder that affects 1 per 50,000 in the general population for Caucasians [47]. It has many names which have been referred to as multiple cartilaginous exostosis [57], osteocartilaginous exostosis, osteochondromatosis, osteogenic disease [41], metachondromatosis [5], and diaphysiary aclasis [3, 11, 20, 21, 23, 25, 27, 28, 31]. HME is the current name that most people use to refer to this condition.

Etiology

HME is an autosomal dominant disorder, mapped to the exostoses genes (EXT). EXT genes are tumor suppressor-related genes encoding glycosyltransferases related to the biosynthesis of heparin sulfate proteoglycan, which is involved in growth signaling pathways in epiphyseal growth plate. They have been known as EXT1, EXT2 [1, 12, 54, 59], and rarely EXT3 [34], and sequence analysis of the EXT loci in HME patients detects that those are located on chromosomes 8q24, 11p11–p12 and 19p, respectively. Benoist-Lasselin et al. [4] state that the defect of heparin sulfate biosynthesis leads to unusual chondrocyte differentiation and promotes phenotypic modification to bone-forming cells.

It has been reported that EXT1 mutation is more related to osteochondroma with more severe anatomic burden (large numbers of exostoses, vertebral location, short statue, more limb malalignment with shorter limb segments and height, more pelvic and flatbone involvement, increased risk of malignant degeneration of the chondrosarcoma) [2, 8, 18, 45], and EXT2 mutation is more related to moderate phenotypes.

It has been reported that 85% of exostoses presents in the solitary form and the other 15% as HME. Several authors agree that approximately two thirds of multiple exostoses patients have a positive family history [8, 17, 40, 42, 44, 50, 55]. While HME has 96% of penetrance of the disease, the concept of incomplete penetrance is considered to support this hereditary ratio [35, 42].

Gender

Several authors have reported that HME has a significant sex ratio skewing with an excess of affected males, while sex skewing has not been observed in nuclear families [35, 37]. Alvarez et al. [2] report that males were affected by a greater number of lesions than females (median number of lesions in males/females, 30 and 18, respectively); however, there was no significant gender difference in limb segment lengths and limb alignment. Gender difference in the development of exostoses might be influenced by the gender difference of growing pattern.

Age

Exostoses develop shortly after birth and continue to develop throughout childhood and into puberty. Studies vary with regard to the average age of presentation. Legeai-Mallet et al. state in their series with 175 patients who had at least two exostoses of the juxta-epiphyseal region of the long bones that HME was detected in some patients at birth, before 5 years in most, and all before the age of 12 years, with the median age of diagnosis at 3 years of age [35]. Khan et al. report that the usual presentation is between 2 and 10 years of age, with most cases having presented by the age of 4 years [32]. Solomon et al. report that 65% [52] and Leone et al. report that 89% [36] of these patients are identified before at 6 years of age. In 2009, Yoshioka et al. report a 24-day-old patient with stiffness at the right long finger due to an osteochondroma from HME, who they operated on at 17 months of age [60].

Clinical Description and Management

Exostoses are either sessile or pedunculated and they vary widely in size and number. The clinical presentation also varies widely due to variable levels of gene expression, and they are basically asymptomatic. Surgical treatment may be required when severe complications or malignant transformation occurs. There can be pain secondary to nerve impingement [10, 33, 46], bony shortening, rotational and angular deformities of the affected appendage [6, 7, 15, 16, 33], and necrosis of the overlying skin [19]. There is also a risk of malignant transformation [6, 7, 10, 49]. All of the above symptoms can be indications for operative intervention [43]. HME patients will require three surgical interventions in their lifetime in average, due to the recurrence of multiple exostoses [47].

Malignant Degeneration

Malignant degeneration is the most severe complication with pain and enlarging masses, which requires surgical intervention. The prevalence of chondrosarcoma transformation in HME has been reported by many authors; however, the figure ranges widely from 0.57% [35] to 25% [27] due to the variation of selection criteria, age distribution of study groups, and length of follow-up time [13, 26, 27, 37, 47, 56]. The peak of incidence occurs at the fourth and fifth decades, which are younger than the cases of primary chondrosarcomas at the sixth decade [14, 53]. Solomon [53] reports that 44% of the site of chondrosarcoma involved the pelvis and proximal femur.

HME in the Hands

Prevalence

The prevalence of multiple exostoses in the hand is very low in nonhereditary conditions [24, 38]. The presence of multiple exostoses in a child’s hand(s) should suggest the possibility that the patient has HME.

Several authors reported the frequency of hand involvement in HME: 0.7% [2], 30% [47], 33% [22], 69% [58], and 79% [52], respectively. Keith [31] states that when the dysplasia was apparent before the age of 6 years, the bones of the hand are more often affected. Cates [9] states that the average age of HME in the hand at X-ray evaluation is 12.1 years.

Affected Lesions

Hand is often involved in HME patients and an average of 11.6 exostoses is found per hand [9]. Exostoses in the hand usually described as occurring in the metaphyseal region and adjacent to a growth plate [6, 7, 16, 48]. Wood [58] reports that the most commonly involved areas were metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints of the long, ring and little fingers. Cates [9] states that most exostoses are located in the juxta-epiphyseal region (61.8%) and typically involved less than 50% of the bone diameter. Karr et al. [30] reported that all patients with osteochondromas located at the distal end of the proximal or middle phalanx will develop angular or rotational deformities if the condition is diagnosed late and left untreated.

Presentation and Management

Common presentation of hand involvement of HME is brachydactyly, phalangeal and metacarpal cone-shaped epiphyses, and clinodactyly. Exostoses close to the interphalangeal joints have been associated with angular and rotational deformities [6, 7, 16]; however, the location and size of the exostosis have no relationship with bone shortening [38]. Early treatment is required to prevent severe deformity in cases of continual growth of the tumors [53], except cases of metacarpal shortening, which usually does not cause functional problems [24].

In this paper, we report the diagnosis of HME in three family members who presented with multiple exostoses within the first 2 years of age. These three patients represent the father, the son, and the daughter, and all three presented at an age earlier than the average age of presentation as reported in the literature. The histological findings with only subperiosteal cartilage without ossification in the resected osteochondroma were consistent with the very early presentation of HME. We believe that this is the earliest reported case in the literature for operative intervention for HME.

Case Report

Patient #1

This 7-year-old right-handed male was first seen at the age of 11 months with a 4-month history of an enlarging nodule on the ulnar aspect of the ring finger nail fold and nail plate associated with a progressive radial clinodactyly at the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint. Significant in this patient’s family history is that his father had multiple exostoses in the hands, hip, knee, and ankles. Except the patient’s father, there was no other family member in either the paternal or maternal pedigree that had HME.

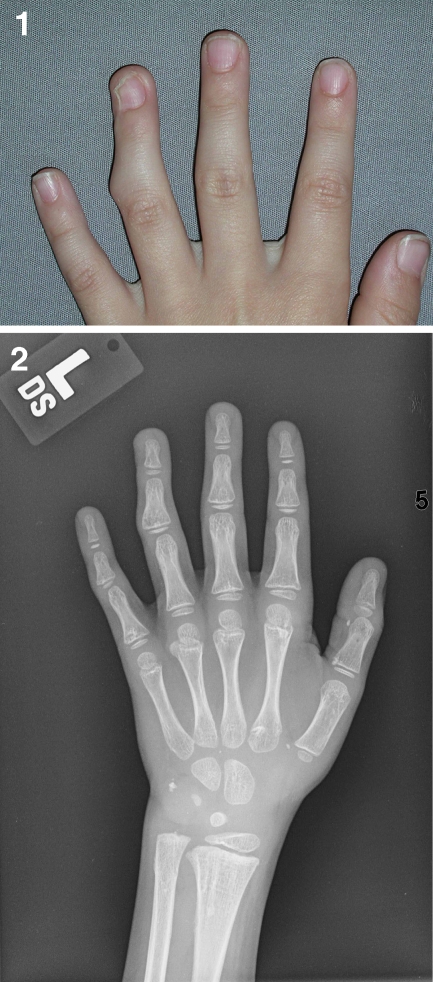

On examination, the nodule measured 7 mm in diameter and there was a 35° radial angulation of the finger at the DIP joint (Fig. 1(1)), suggesting an attenuation or disruption of the ulnar collateral ligament due to the exostosis. Another nodule was felt at the radial aspect at the base of the right small finger in the web space. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of his left hand was obtained and an exostosis was seen on the proximal ulnar surface of the distal phalanx of his left ring finger (Fig. 1(2)). Based on these clinical findings and his family history, these nodules were felt to be consistent with a diagnosis of HME.

Fig. 1.

1 An enlarging nodule on the ulnar aspect of the left ring finger nail fold and nail plate, associated with a progressive 35° radial clinodactyly at the DIP joint. 2 The low intensity area by T1 MRI shows an exostosis on the proximal ulnar surface of the distal phalanx of his left ring finger. 3 An intraoperative picture illustrates the appearance of the exostosis, which was resected from the left ring finger at the DIP joint. 4 Osteochondroma from the distal phalanx of his left ring finger. The osteochondroma is poor subperiosteal cartilage. It has not yet developed endochondral bone formation. This pattern is consistent with a very early osteochondroma. 5 Current photograph shows long-term joint correction 7 years after the surgery

The first surgery was done at the age of 13 months. The large exostosis in the left ring finger was excised through a dorsal–ulnar incision (Fig. 1(3)), with repair of the attenuated ulnar collateral ligament. The DIP joint was corrected to 0° of deviation and held in position with a 28/1,000-in. K-wire. Histologically, the lesion was consistent with a cartilage nodule arising from the bone surface. Endochondral ossification had not yet taken place in the stalk. This was felt to be consistent with an osteochondroma (Fig. 1(4)). Postoperatively, the patient did well. He had full active motion in the ring finger with a stable DIP joint with complete correction of the angular deformity with minimal distortion of the nail plate. He has had long-term correction and stability of his DIP joint (Fig. 1(5)).

The patient continued to develop more exostoses in the hands, feet, and left clavicle, requiring more surgeries due to symptomatic pain and functional difficulties with finger deviation secondary to the progressive increase in the size of the nodules. (Fig. 2(1, 2)). At 3 years of age, he underwent a second surgery to remove three exostoses from the hand: one from the left index finger at the proximal phalanx (3 mm), a second from the left index finger at the metacarpophalangeal (MP) joint (4 mm), and a third from the left ring finger at the MP joint (10 mm) (Fig. 3). The patient also underwent removal of two exostoses from the lower extremities: one from the right great toe and the other from the left distal tibia above the malleolus.

Fig. 2.

1 A radiograph shows two exostoses: one is on the right great toe, which was resected at the second surgery. The other is on the right medial malleolus, which was resected at the third surgery. 2 A radiograph shows two of three exostoses, which were resected at the third surgery: one on the first web space of the left foot, the second on the left distal tibia

Fig. 3.

A radiograph shows three exostoses on the left hand: one on the index finger at the proximal phalanx, a second from the index finger at the MP joint, a third from the ring finger at the MP joint

A third surgery was done at 6 years of age. Radiographs show (Fig. 4(1)) two exostoses, one at the right long finger at the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint, measuring 5 mm, which does not have a stalk to the phalanx, and the other at the right index finger at the proximal metacarpal bone. The patient also had three other exostoses removed from the lower extremities: one from the first web space of the left foot, the second from the left distal tibia, and the third from the right medial malleolus. He did well and had no complications. Histologically, these entire lesions were identical, with a sessile bone prominence with a cartilaginous cap (Fig. 4(2)).

Fig. 4.

1 A radiograph shows two exostoses on the right hand, one at the middle finger at the PIP joint, which does not have a stalk to the phalanx, and the other at the index finger at the proximal metacarpal bone. 2 Osteochondroma from the right index finger at the proximal metacarpal bone. The osteochondroma is sessile with endochondral bone formation beneath it

He again was symptomatic with his exostosis (Fig. 5(1)). He underwent his fourth surgery at 7 years of age. Six exostoses were removed from the left index finger at the MP joint, the left middle finger at the MP joint, the left ring finger at the PIP and the MP joint, and the left small finger at the PIP and the MP joint (Fig. 5(2)).

Fig. 5.

1 The patient was symptomatic again with six enlarging nodules on the left hand: especially one on the index finger at the MP joint, and two on the ring finger at the PIP and the MP joint. 2 A radiograph shows six exostoses on the left hand, at the index finger at the MP joint, the middle finger at the MP joint, the ring finger at the PIP and the MP joint, and left small finger at the PIP and the MP joint

The patient has done well from all these surgeries. He continues to have multiple lesions, which remain asymptomatic: three in the right hand, three in the right foot, one in the right ankle, and one over the left clavicle.

Patient #2

A younger sibling of patient #1 was born 4 years later. She was the younger of two fraternal twins (one boy and one girl). She also has multiple exostoses in the hands and the feet. The sister presented at 24 months of age with a 4-month history of finger nodules. Physical examination showed palpable nodules on the radial dorsal aspect of the right index finger at the DIP joint and at the ulnar palmar aspect of the right long finger at the distal proximal phalanx. A radiograph (Fig. 6) shows that there is no stalk between the nodule and the right index finger similar to the case of her elder brother. Currently, she has no deviation of the fingers, appears not to be symptomatic, and has no functional problems. She has not had surgery and she will be followed routinely.

Fig. 6.

A radiograph (patient #2) shows two exostoses on the right hand, one at the index finger DIP joint, which does not have a stalk to the phalanx, and the other on the long finger at the distal proximal phalanx

Patient #3

The third patient is the father of patient #1 and patient #2. He is older by 30 years than patient #1. He is the first person in his family to present with multiple exostoses. His nodules were identified early when he was very young. He did not undergo surgery though until he was 6 years old. Six exostoses were removed: one from the right ring finger at the palmar side of the PIP joint, a second from the right middle finger at the dorsal side of the MP joint, a third from the right index finger at the web space, a fourth from the left middle finger at the palmar MP joint, a fifth and a sixth from the right and left index finger at the dorsal aspect of the DIP and the MP joint, respectively. He has since been asymptomatic since his surgery and has no functional problems (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Thirty-one years after the operation, patient #3 does not present either recurrence or functional deformity

Discussion

Since Johns Hunter mentioned about HME for the first time in 1786 (1) in a lecture, many studies are performed about this autosomal dominant disorder. However, exostoses are basically asymptomatic and those lesions remain undiagnosed; therefore, the prevalence of HME varies widely in different studies.

In the cases we presented, the histological findings of immature osteochondromas reflect the early detection and presentation of the exostoses prior to the age of 2 years. The osteochondromas of HME in general are characterized by bone nodules with either sessile (broad based) or pedunculated (with stalk) cartilage caps with an exterior of periosteum and walls of compact bone and a trabecular interior. However, in our patients, osteochondroma was noted to be a subperiosteal cartilaginous nodule that had not yet begun to ossify (Fig. 1(1, 2)). These histological findings are felt to represent exostoses in its early phase of development, in essence an immature osteochondroma.

The radiograph of his sister, patient #2 (Fig. 6), also shows that there is no stalk between the nodule and the right index finger similar to patient #1. It is likely that with continued observation, these “immature” exostoses will continue to develop and mature findings of exostoses presentation will become apparent.

Brachydactyly is one of the common presentations of HME in the hands, and early treatment is essential to prevent severe residuals. Due to early diagnosis and treatment of the ring finger exostosis, patient #1 has minimum angular deformity without any functional deficit. The early diagnosis of the singular exostosis, in patient #1, facilitated the detection of multiple exostoses in his feet, ankles, and the clavicle.

The frequency of exostoses hand involvement is low except HME cases, so these surface cartilage nodules in his hand at the early age should be a clue to the fact that the patient has HME, which led to early detection of his other lesion and early diagnosis of his younger sister, patient #2.

To our knowledge, our surgery performed on patient #1 at the age of 13 months is the earliest reported surgery on a patient with HME to date. Previously, the earliest reported surgical case was done on a 17-month-old by Yoshioka et al. in 2010 [36]. The presentation of HME varies in size and location even within families. These family members demonstrate several patterns of early presentations of HME, which is histologically unique in its sessile subperiosteal cartilage cap without ossification. This report plays an important role for early diagnosis by understanding the variety of HME presentation.

Footnotes

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

References

- 1.Ahn J, Ludecke HJ, Lindow S, et al. Cloning of the putative tumor suppressor gene for hereditary multiple exostoses (EXT1) Nature Genet. 1995;11:137–143. doi: 10.1038/ng1095-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez C, Tredwell S, Vera M, Hayden M. The genotype–phenotype correlation of hereditary multiple exostoses. Clin Genet. 2006;70:122–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2006.00653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beals RK. Metachondromatosis. Clin Orthop. 1982;169:167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benoist-Lasselin C, Margerie E, Gibbs L, et al. Defective chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation in osteochondromas of MHE patients. Bone. 2006;39(1):17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyer A. Traité de maladies chirurgicales vol 3. Paris: Ve Migneret; 1814. p. 594. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyes JH. Bunnell’s surgery of the hand. 5. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1970. pp. 693–4. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carroll RE. Tumors of the hand skeleton. In: Flynn JE, editor. Hand surgery. 3. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1982. pp. 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carroll KL, Yandow SM, Ward K, et al. Clinical correlation to genetic variations of hereditary multiple exostosis. J Pediatr Orthop. 1999;19:785–91. doi: 10.1097/00004694-199911000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cates HE, Burgess RC. Incidence of brachydactyly and hand exostosis in hereditary multiple exostosis. J Hand Surg. 1991;16(1):127–32. doi: 10.1016/S0363-5023(10)80027-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coley BL, Higinbothtam NL. Tumors primary in the bones of the hands and feet. Surgery. 1935;5:112–28. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cook W, Raskin W, Blanton SH, et al. Genetic heterogeneity in families with hereditary multiple exostoses. Am J Hum Genet. 1993;53:71–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cook A, Raskind W, Balanton SH, Pauli RM, et al. Genetic heterogeneity in families with hereditary multiple exostoses. Am J Hum Genet. 1993;53:71–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dahlin DC. Bone tumours. Springfield: Thomas; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dahlin DC, Henderson ED. Chondrosarcoma, a surgical and pathological problem: review of 212 cases. J Bone Jt Surg. 1956;38-A:1025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ehrenfiled A. Hereditary deforming chondrodysplasia multiple cartilaginous exostoses: a review of the American literature and report of twelve cases. JAMA. 1917;68:502–8. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fairbank HA. Diaphyseal acalasis. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 1949;31:105–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faiyaz-Ul-Haque M, Ahmad W, Zaidi SHE, et al. Novel mutations in the EXT1 in two consanguineous families affected with multiple hereditary exostoses (familial osteochondromatosis) Cl Genet. 2004;66:144–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2004.00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Francannet C, Cohen-Tanugi A, Merrer M, et al. Genotype–phenotype correlation in hereditary multiple exostoses. J Med Genet. 2001;38:430–34. doi: 10.1136/jmg.38.7.430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ganzhorn RW, Bahri G, Horowitz M. Osteochondroma of the distal phalanx. J Hand Surg. 1981;6:625–6. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(81)80149-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guy’s Hospital Reports Case of cartilaginous exostosis. Lancet. 1825;2:335. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heike HVA. On ossification and growth of certain bones of the rabbit, with a comparison of the skeletal age in the rabbit and in man. Acta Orthop Scand. 1959;29:171. doi: 10.3109/17453675908988796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hennekam RC. Hereditary multiple exostoses. J Med Genet. 1991;28:262–6. doi: 10.1136/jmg.28.4.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hunter J. The works of John Hunter, vol I. London: Longman, Rees Orme Brown Green & Longman; 1837. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huvos AG. Bone tumors. Diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. 2. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iglesias A, Vázquez J, Mendoza CA. Enfermedades metabólicas del hueso, vols 1–2. Santafé de Bogotá. Colombia: Imprenta INS; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaffe HL. Hereditary multiple exostosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1943;36:335–57. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jaffe HL. Tumors and tumorous conditions of the bones and joints. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1958. pp. 117–141. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jansen M. Dissociation of bone growth. In: Robert Jones birthday volume. London: London University Press; 1928. p. 43.

- 29.Jones KB, Morcuende JA. Of hedgehogs and hereditary bone tumors: re-examination of the pathogenesis of osteochondromas. Iowa Orthop J. 2003;23:87–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karr MA, Aulicino PL, DuPuy TE, et al. Osteochondromas of the hand in hereditary multiple exostosis: report of a case presenting as a blocked proximal interphalangeal joint. J Hand Surg. 1984;9:264–8. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(84)80157-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keith A. Studies on the anatomical changes which accompany certain growth-disorders of the human body. J Anat. 1920;54:101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khan AN, Al-Salman MJ, MacDonald S. Osteochondroma and osteochondromatosis. Published online in 2009 at http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/392546-overview, accessed 13 Aug 2010.

- 33.Kyle BH, Mundy BK. Multiple osteochondromata of the hand. VA Med Monthly. 1952;79:36–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Merrer M, Legeai-Mallet L, Jeannin PM, et al. A gene for hereditary multiple exostoses maps to chromosome 19p. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3:717–22. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.5.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Legeai-Mallet L, Munnich A, Maroteaux P, et al. Incomplete penetrance and expressivity skewing in hereditary multiple exostoses. Clin Genet. 1997;52:12–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1997.tb02508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leone NC, Shupe JL, Gardner EJ, et al. Hereditary multiple exostosis. A comparative human–equine–epidemiologic study. J Hered. 1987;78:171–7. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a110351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luckert-Wicklund LC, Pauli RM, Johnston D, Hecht JT. Natural history study of hereditary multiple exostoses. Am J Med Genet. 1995;55:43–6. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320550113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moore JR, Curtis RM, Wilgis EFS. Osteocartilaginous lesions of the digits in children: an experience with 10 cases. J Hand Surg. 1983;8:309–15. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(83)80167-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murphy MD, Choi JJ, Kransdorf MJ, et al. Imaging of osteochondroma: variants and complications with radiologic–pathologic correlations. Radiographics. 2000;20(5):1407–34. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.5.g00se171407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Noonan KJ, Levenda A, Snead J, et al. Evaluation of the forearm in untreated adult subjects with multiple hereditary osteochondromatosis. J Bone Joint Surg. 2002;84-A:397–403. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200203000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ombredanne L. Précis clinique opératoire de chirurgie infantile. 4. Paris: Masson & Cie; 1944. pp. 69–77. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peterson HA. Multiple hereditary osteochondromata. Clin Orthop. 1989;239:222–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pierz KA, Stieber JR, Kusumi K, et al. Hereditary multiple exostoses: one centre’s experience and review of etiology. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;401:49–59. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200208000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Porter DE, Emerton ME, Villanueva-Lopez F, et al. Clinical and radiographic analysis of osteochondromas and growth disturbance in hereditary multiple exostoses. J Pediatr Orthop. 2000;20:246–50. doi: 10.1097/00004694-200003000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Porter DR, Lonie L, Fraser M, et al. Severity of disease and risk of malignant change in hereditary multiple exostoses. J Bone Joint Surg. 2004;86-B(7):1041–6. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.86B7.14815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Posch JL. Tumors of the hand. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1956;38:517–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schmale GA, Conrad EU, Raskind WH. The natural history of hereditary multiple exostoses. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1994;76-A:986–92. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199407000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shapiro F, Simon S, Glimcher MJ. Hereditary multiple exostoses: anthropometric, roentgenographic, and clinical aspects. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1979;61:815–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shellito JG, Dockerty MB. Cartilaginous tumors of the hand. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1948;86:465–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Skinner R, Beall DP, Webb HR, et al. Calcaneal osteochondroma. Okla State Med Assoc. 2007;100:120–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Solomon L. Bone growth in diaphysial aclasis. J Bone Joint Surg. 1961;43B:700–16. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.43B4.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Solomon L. Hereditary multiple exostoses. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 1963;45:292–304. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Solomon L. Chondrosarcoma in hereditary multiple exostosis. S Afr Med J. 1974;48:671–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stickens D, Clines G, Burbee D, et al. The EXT2 multiple exostoses gene defines a family of putative tumor suppressor genes. Nat Genet. 1996;14:25–32. doi: 10.1038/ng0996-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vanhoenacker FM, Hul W, Wuyts W, et al. Hereditary multiple exostoses: from genetics to clinical syndrome and complications. Eur J Radiol. 2001;40:208–17. doi: 10.1016/S0720-048X(01)00401-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Voutsinas S, Wynne-Davis R. The infrequency of malignant disease in diaphyseal aclasis and neurofibromatosis. J Med Genet. 1983;20:345–9. doi: 10.1136/jmg.20.5.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wiedeman HR, Gross KR, Dibbern H. An atlas of characteristic syndromes. Chicago: Year Book Medical; 1985. pp. 306–7. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wood VE, Molitor C, Mudge MK. Hand involvement in multiple hereditary exostosis. Hand Clin. 1990;6(4):685–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wuyts W, Hul W, Wauters J, et al. Positional cloning of a gene involved in hereditary multiple exostoses. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:1547–57. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.10.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yoshioka S, Hamada Y, Takata S, et al. An osteochondroma limiting flexion of the proximal interphalangeal joint in hereditary multiple exostosis: a case report. Hand (NY) 2010;5(3):299–302. doi: 10.1007/s11552-009-9232-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]