Abstract

Scaphoid nonunion followed by necrosis of bone segments is a common pathologic condition for the hand surgeon, and the difficulty of its management is well known. The total titanium scaphoid replacement, although not well-described in the literature, in our experience represents a reasonable choice in the treatment of this condition. Strict patient selection is necessary to achieve good clinical results. The titanium avoids the silicone synovitis, a well-described complication of silastic implants. Furthermore, this technique permits other surgical steps in case of failure.

Keywords: Carpal implant, Scaphoid replacement, Scaphoid nonunion

Introduction

The pitfalls of treatment of scaphoid fractures are very common in the current practice: the well-known sequelae are nonunion, necrosis of the fragments, carpal biomechanical changes leading to scaphoid nonunion advanced collapse arthritis and ultimately, severe degenerative arthritis of the entire radio-carpal and intercarpal joints. Many treatments have been proposed in the hand surgery literature in order to reconstruct the scaphoid bone, or, when that is impossible, to prevent or treat the late sequelae. These procedures are commonly performed in most hand surgery centers: bone grafts (free or pedicled when the non-union is isolated, without collapse phenomena; [6, 7, 10–12, 16, 21]), partial or total scaphoid removal in association with midcarpal arthrodesis, proximal row carpectomy [3, 10], total wrist replacement or total wrist arthrodesis [4]. A partial pyrocarbon scaphoid implant has recently been introduced, but there is little discussion currently of total scaphoid implant replacement.

The first scaphoid prosthesis, made of vitallium, was proposed by Waugh and Reuling in 1945, and then by Legge in 1951 [5] and Metcalfe in 1954. An acrylic implant was created by Agner in 1963 [13]. All of these were essentially custom devices.

In 1962, Swanson introduced a Silastic prosthesis [1, 8, 10, 17, 19], which was subsequently adopted worldwide, until the severe problems of silicone synovitis were observed in longer term follow-up. It is interesting to note that the great majority of papers describing the complications of silastic scaphoid implants did not report other biomechanical or anatomical problems; the only, and well-founded criticism was against the silicone synovitis and the severe wrist destruction generated by the particulate debris generated from the implants. In response to these problems, Swanson in 1989 developed a titanium implant. This solution should avoid the “siliconitis” phenomena, while maintaining the good anatomic and biomechanical early results of the silicone scaphoid implant, but the titanium device never achieved the popularity of the silicone model, and the literature data are very poor about it.

The senior author was part of the development team for the titanium scaphoid implant for Wright and started to use it when it was distributed in Italy by Major S.p.A. This paper describes a 15-year experience with this device.

The scaphoid total replacement can be considered when three conditions are evident in pre-operative clinical evaluation of scaphoid necrosis [14, 15, 18, 20]:

Scaphoid destruction, unsuitable for a reconstruction with grafting techniques;

Good wrist stability and absence of a scaphoid nonunion advanced collapse (SNAC) wrist condition, as demonstrated by carpal height and radio-lunate angle measurements.

absence of degenerative changes in the radial scaphoid facet and/or other carpal bones

Correspondingly, contraindications to scaphoid replacement include: radial scaphoid facet degeneration; a previously performed radial styloidectomy; any sign of carpal collapse and deformity of the distal radius consequent to displaced fracture; a diminution of the McMurtry index (i.e., the radiographic ratio between the carpal height and the length of the third metacarpal bone: normally it is 0.54 ± 003); any increase in the radio-lunate angle [10]; or degenerative arthritis of other carpal bones, in particular at the midcarpal joint.

Materials and Methods

Between January 1993 and September 2008, the senior author has performed total scaphoid prosthetic replacement in113 patients (102 men, 11 women), with an average age of 38.3 years (minimum 18–maximum 62 years). There were 87 right wrists and 26 left wrists involved. All patients had a scaphoid nonunion with necrosis and had failed conservative (Figs. 1 and 2) or surgical treatment, including screw fixation, Matti–Russe grafting, and vascular bone grafting. None of these patients had X-rays signs of radio-carpal arthritis or SNAC wrist (Figs. 1 and 2). The average time between the initial injury or previous surgical treatment and diagnosis of scaphoid nonunion was 18 months (minimum 3 months–maximum 25 years).

Fig. 1.

Typical pre-operative MRI image of a case of scaphoid nonunion with wide necrosis areas

Fig. 2.

Typical pre-operative X-ray image of a case of scaphoin nonunion. There is no evidence of radio-carpal arthritis or SNAC wrist

The surgical technique consists of a dorsal approach between the extensor carpi radialis brevis and extensor pollicis longus; the wrist capsule with the radio-carpal dorsal ligament is cut in a “T-shape” and dissected from the radius and carpal bones so that the necrotic scaphoid is exposed and isolated. After its removal (a small, volar portion of the distal pole, of about 3 × 3 mm, must be left in place to preserve the radio-scapho-capitate ligament insertion), a hole into trapezium body is prepared: it will be the place of the distal prosthetic stem, which is one of the key points of stability of the implant (Fig. 3). Prosthetic oversizing must be avoided to prevent the risk of excessive pressure on the distal radius. In case of doubt about the implant size, we recommend to choose the smaller. Before positioning the definitive prosthesis, the wrist stability is tested with a trial prosthesis. Passive flexion, extension, ulnar, and radial deviation and rotations are then examined. The definitive prosthesis is then put in place. The distal stem is inserted into the trapezium and the prosthesis is fixed by a Ti-cron 2/0 suture (any similar size of non-resorbable suture can be used) passed into a hole inside the body of capitate and a hole in the implant body (Fig. 4). After confirming satisfactory position radiographically (Fig. 5), the dorsal capsule is closed and a suction drain is left in place for 24 h just to prevent hematoma formation. The day after surgery, the dressing is changed, and a thermoplastic splint is applied with wrist in 10° extension. Immobilization is maintained for 4 weeks, when X-ray examination will be executed to confirm satisfactory position of the implant, after which rehabilitation can begin.

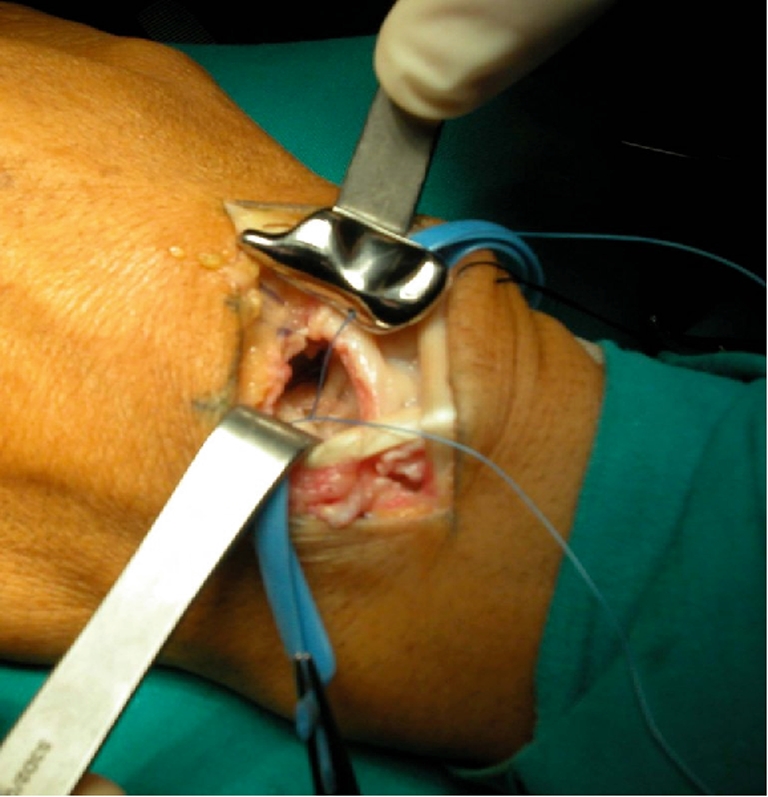

Fig. 3.

Intra-operative view. After removal of necrotic scaphoid the prosthetic trial implants of different sizes are put in place, and the best of them is chosen, once its stability is verified and the absence of impingement documented

Fig. 4.

The titanium prosthesis is put in place; a non-resorbable wire passing through the prosthetic body will be fixed to the capitate

Fig. 5.

Per-operative X-ray control: the prosthesis position is correct

Clinical and X-ray checks are performed at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months after the surgical intervention to follow the restoration of range of motion and to detect any early displacement of the implant after motion start.

Results

We have been able to follow 75 patients with a mean follow-up of 46 months (minimum 6–maximum 152 months). The other 38 are considered lost at follow-up (the observation period was less than 6 months for 22 of them; the other 16 patients had discontinuous follow-up: after first control, they did not respect the official observation time as the above-described control). The evaluation criteria [18, 20] include satisfactory position of the implant on the most recent X-rays, the active and passive range of motion of the wrist, wrist stability, the presence of any pain, the degree of satisfaction of the patients. The X-rays were assessed to identify any scapho-lunate dissociation, the carpal height (McMurtry) index and the correct scapho-lunate angle. The X-rays are also useful to show the correct position of prosthetic stem into trapezium body, any evidence of reabsorption or cysts in the carpal bones, and any early sign of distal radial wear.

The clinical findings (Table 1) demonstrated that 26% of patients achieved full wrist ROM. In 48% of cases, a range between 50° in extension and 60° in flexion was achieved; in 25% of patients a diminution of the motion was observed, although sufficient for daily activities (Figs. 6 and 7). The average grip strength (Jamar) test was 80% of the contralateral side (min. 65–max. 95). In 85% of cases, the patients were painless; the pain was mild in 8% and bothersome, especially during bearing, in 7%. Almost all (94%) patients were satisfied.

Table 1.

The clinical findings

| Excellent results (20 pts) | Satisfactory results (36 pts) | Poor results (19 pts) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active ROM | Extension 85° | Extension 50° | Extension ≤ 40° |

| Flexion 80° | Flexion 60° | Flexion ≤ 40° | |

| Grip strength | 80–95% | 60–80% | ≤ 60% |

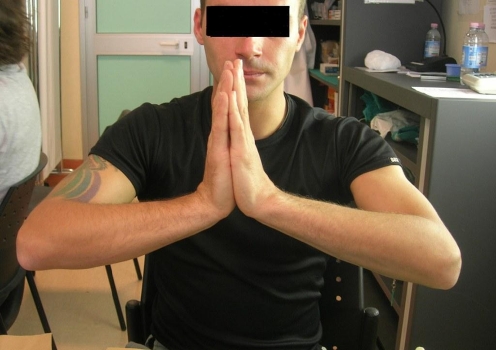

Fig. 6.

Clinical findings of an excellent result at 6 months follow-up after replacement in the left wrist

Fig. 7.

Clinical findings of an excellent result at 6 months follow-up after replacement in the left wrist

The results have also been evaluated by the DASH (applied to 60 patients) and PRWE (30 patients; introduced in our center in 2005; [2, 9]) questionnaires at 3, 6, and 12 months. The results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Results evaluated by the DASH and PRWE

| 3 months | 6 months | 12 months | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DASH score (60 patients) | 80% (48/60), <60 | 92% (55/60), <50 | 94% (56/60), <45 |

| 12% (7/60), 61–110 | 7% (4/60), 51–100 | 5% (3/60) , 46–100 | |

| 8% (5/60), 111–130 | 1% (1/60), >111 | 1% (1/60), >101 | |

| PRWE pain scale | 85% (25/30), 3–20 | 91% (27/30), 3–8 | 94% (28/30), 1–7 |

| 0 (best)–50 (worst) (30 patients) | 10% (3/30), 21–25 | 9% (3/30), >8 | 6% (2/30), >7 |

| 5% (2/30), >25 |

The tables show that, 6 months after surgery, the results are nearly definitive and the difference of the scores at 6 and 12 months is quite poor.

In the 75 cases we have followed, the results have been uniformly stable after 6 months. The patients with a long follow-up (until 15 years) show a stable result in the time (Fig. 8). In all cases, the previous occupation has been maintained or resumed. We have observed five cases of mechanical failure, where a volar rotation of the implant and a DISI have been shown on X-rays examination, due to dislocation of the distal stem, but only two of these required a re-intervention. In one case, the implant was replaced, and in the other one, it was necessary to remove the implant and perform a four-corner arthrodesis (Fig. 9). The other three patients underwent a moderate carpal collapse, with a loss of range of motion, with no or moderate pain, and preferred no further surgery (Figs. 10 and 11).

Fig. 8.

X-rays after 12 years: no displacement or signs of radial surface wear, no bone cysts, or other problems

Fig. 9.

Implant dislocation: patient treated with implant removal and four-corner arthrodesis

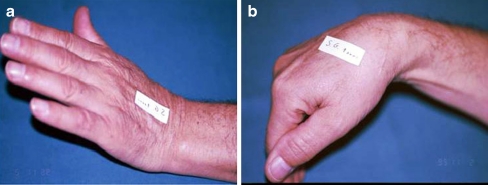

Fig. 10.

a, b Implant rotation at 2 and 7 years after surgery

Fig. 11.

a, b: same patient as Fig. 10: sufficient function and strength: the patient was satisfied and rejected new surgery

In no case, even in the longer-term cases (followed more than 10 years), did we observe problems related to radial surface wear, carpal reabsorption cysts, or intolerance to the implant material.

Discussion

By our opinion, total scaphoid implant is a very good choice because this technique has some unquestionable advantages:

The restoration of wrist anatomy and carpal biomechanics very close to the normal features. Our results demonstrate a high rate of excellent and good results.

The fact that only the affected bone is involved in surgery

The fact that, in case of failure, the same more aggressive procedures to be considered as alternatives are always possible, such as scaphoidectomy and four-corner arthrodesis or proximal row carpectomy. In our experience, only in one case did we have to convert the procedure, removing the implant and performing a four-corner arthrodesis.

The satisfactory use of the implant is based on strict attention to the key-stones described: a correct preoperative indication, a precise technical execution that warrants the preservation of the elements of prosthetic stability (the volar and dorsal ligaments, the distal stem), and correct implant sizing. Essentially, the prosthetic stem creates the same effect as a scapho–trapezium–trapezoid arthrodesis: the loads shift from the radio-scaphoid joint to the scapho–trapezium–trapezoid complex. The radio-scapho-capitate ligament, volar, and the scapho-trapezium ligament, dorsal, serve as further support of stability. The volar ligament is preserved by the dorsal approach; the dorsal ligament must be reconstructed after prosthesis positioning.

The dorsal surgical approach allows the surgeon to preserve all volar ligaments of the wrist, assuring the integrity of a palmar wall that may support the prosthesis during loading. The prosthetic stability that we observed confirms the relatively minor importance of the scapho-lunate complex ligament for maintaining carpal stability, when the distal scaphoid stability is preserved.

Although this method has not been previously well described, in our experience, the technique is a very reliable one, and in our opinion, titanium scaphoid implant arthroplasty is a valid alternative to classic and more invasive interventions, such as scaphoidectomy and partial carpal arthrodesis, and in our practice currently represents the first choice of treatment whenever it is indicated.

References

- 1.Agner O. Treatment of nonunited navicular fractures by total excision of the bone and the insertion of acrilic prostheses. Acta Orthop Scand. 1963;33:236–245. doi: 10.3109/17453676308999850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashcroft GP, Netto DCD. Alsindi Z Silicone replacement for non-union of the scaphoid: 7 cases followed for 9 (5–18) years. Acta Orthop Scand. 1993;64:472–474. doi: 10.3109/17453679308993671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crabbe WA. Excision of the proximal row of the carpus. J Bone Joint Surg. 1964;46B:708–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hastings H, Boyer MI Total wrist arthrodesis. In: Watson HK, Weinzweig J, The wrist, Lippincot Williams & Wilkins, 2001: 555–566.

- 5.Haussman P. Long-term results after silicone prosthesis replacement of the proximal pole of the scaphoid bone in advanced scaphoid nonunion. J Hand Surg. 2002;5:417–23. doi: 10.1054/jhsb.2002.0758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Judet R, Roy-Camille R, Guillamon JL. Traitement de la pseudarthrose du scaphoïde carpien par le greffon pédiculé. Rev Chir Orthop. 1972;7:699–705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuhlmann N, Mimoun M, Boabighi A. Baux S Vascularized bone graft pedicled on the volar carpal artery for nonunion of the scaphoid. J Hand Surg. 1987;12B:203–210. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681_87_90014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Legge R. Vitallium prostheses in the treatment of fracture of the carpal navicular. West J Surg. 1951;59:468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacDermid JC, Turgeon T, Richards RS, Bearle M. Roth JH Patient rating of wrist pain and disability: a reliable and valid measurement tool. J Orthop Trauma. 1998;12:577–86. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199811000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mack GM, Lichtman DM, Scaphoid non-union. In: Lichtman DM, The wrist and its disorders, WB Saunders Company, 1988: 293–328.

- 11.Mathoulin C. Haerle M Vascularized bone graft from the carpal palmar artery for treatment of scaphoid non-union. J Hand Surg. 1998;23B:318–323. doi: 10.1016/s0266-7681(98)80049-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mathoulin C. Brunelli F Further experience with the index metacarpal vascularized bone graft. J Hand Surg. 1998;23B:311–317. doi: 10.1016/s0266-7681(98)80048-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pequignot JP, Lussiez B, Allieu Y. A adaptive proximal scaphoid implant. Chir Main. 2000;19:276–85. doi: 10.1016/S1297-3203(00)73492-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rossello MI. Trattamento negli insuccessi nella patologia dello scafoide: le protesi. Riv Chir Mano. 2001;38:150–157. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rossello MI, Costa M, Bertolotti M. Pizzorno V la sostituzione protesica dello scafoide carpale. Riv Chir Riabil Mano Arto Super. 1994;31:81–87. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shin AY. Bishop AT Pedicled vascularized bone grafts for disorders of the carpus: scaphoid nonunion and Kienbock’s disease. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2002;10:210–216. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200205000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swanson AB. Silicone rubber implants for replacement of carpal bones. Orthop Clin North Am. 1970;1:299–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swanson AB, Groot Swanson G, DeHeer DH, Pierce TD. Carpal bone titanium implant arthroplasty- Ten years’ experience. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;342:46–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swanson AB, Groot Swanson G, Maupin BK. Scaphoid implant resection arthroplasty. Long term results. J Arthroplasty. 1986;1:47–62. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(86)80009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Viegas SF, Patterson RM, Peterson PD, Crossley M. Foster R The silicone scaphoid: a biomechanical study. J Hand Surg. 1991;16A:91–97. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(10)80019-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zaidemberg C, Siebert JW, Angrigiani C. A new vascularized bone graft for scaphoid nonunion. J Hand Surg. 1991;16A:474–478. doi: 10.1016/0363-5023(91)90017-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]