Abstract

Epigenetic regulation, which includes changes in DNA methylation, histone modifications, and alteration in microRNA (miRNA) expression without any change in the DNA sequence, constitutes an important mechanism by which dietary components can selectively activate or inactivate gene expression. Curcumin (diferuloylmethane), a component of the golden spice Curcuma longa, commonly known as turmeric, has recently been determined to induce epigenetic changes. This review summarizes current knowledge about the effect of curcumin on the regulation of histone deacetylases, histone acetyltransferases, DNA methyltransferase I, and miRNAs. How these changes lead to modulation of gene expression is also discussed. We also discuss other nutraceuticals which exhibit similar properties. The development of curcumin for clinical use as a regulator of epigenetic changes, however, needs further investigation to determine novel and effective chemopreventive strategies, either alone or in combination with other anticancer agents, for improving cancer treatment.

Keywords: Curcumin, Epigenetics, Histone acetyltransferase, Histone deacetyltransferase, DNA methyltransferase, microRNA

Introduction

Epigenetics, heritable changes in gene expression that occur without a change in the DNA sequence, constitute an important mechanism by which dietary components can selectively activate or inactivate gene expression (Davis and Ross 2007). Epigenetic mechanisms include changes in DNA methylation, histone modifications, and altered microRNA (miRNA) expression (Yoo and Jones 2006; Winter et al. 2009).

Changes to the structure of chromatin influence gene expression by either inactivating genes, which occurs when the chromatin is closed (heterochromatin), or by activating genes when the chromatin is open (euchromatin) (Rodenhiser and Mann 2006). The nucleosome (Fig. 1a), which is the fundamental repeating unit of chromatin, is composed of DNA wrapped around a histone octamer, formed by four histone partners, an H3-H4 tetramer, and two H2A-H2B-dimers. Each successive nucleosomal core is separated by a DNA linker associated with a single molecule of histone H1. Chromatin modifications usually occur at the amino acids of the N-terminal tails of histones (Fig. 1b) and either facilitate or hinder the association of DNA repair proteins and transcription factors with chromatin. These core histones undergo a wide range of post-translational modifications, including acetylation, controlled by histone acetyltransferases (HATs), and associated with gene expression (Zhang and Dent 2005); deacetylation, controlled by histone deacetylases (HDACs), and associated with gene inactivation; and methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, sumoylation, ADP-ribosylation, and possibly biotinylation (Davis and Ross 2007).

Fig. 1.

a The fundamental repeating unit of the chromatin is the nucleosome. A single nucleosomal core is composed of a DNA fragment wrapped around a histone octamer, formed by an H3-H4 tetramer and two H2A-H2B dimers. Each successive nucleosomal core is separated by a DNA linker associated with a single molecule of histone H1. b Chromatin modifications usually occur at the amino acids of the N-terminal tails of histones. These histone tails are the site for a wide range of post-translational modifications, including acetylation controlled by histone acetyltransferases (HATs), deacetylation controlled by histone deacetylases (HDACs), and methylation controlled by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs)

In addition, epigenetic factors can also affect the expression of miRNAs (Croce 2009). Aberrant expression of miRNAs can arise through numerous mechanisms, including genomic abnormalities, transcriptional regulation, and processing of miRNAs (Winter et al. 2009). miRNAs are small, endogenous, single-stranded RNAs of 19–25 nucleotides in length that regulate gene expression, for example, by binding imperfectly to the 3′ untranslated region of target mRNAs, leading to translational repression, or by targeting mRNA cleavage because of the imperfect complementarity between miRNA and mRNA.

Recently, natural compounds, such as curcumin, epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), and resveratrol, have been shown to alter epigenetic mechanisms, which may lead to increased sensitivity of cancer cells to conventional agents and thus inhibition of tumor growth (Li et al. 2010). Curcumin (diferuloylmethane), a yellow spice and the active component of the perennial herb Curcuma longa, commonly known as turmeric (Aggarwal and Sung 2009), is one of the most powerful and promising chemopreventive and anticancer agents, and epidemiological evidence demonstrates that people who incorporate high doses of this spice in their diets have a lower incidence of cancer (Wargovich 1997). Furthermore, epidemiological evidence exists indicating that there is a correlation between increased dietary intake of antioxidants and a lower incidence of morbidity and mortality (Devasagayam et al. 2004). For instance, a population-based case–control study in approximately 500 newly diagnosed gastric adenocarcinoma patients and approximately 1,100 control subjects in Sweden found that the total antioxidant potential of several plant-based dietary components was inversely associated with gastric cancer risk (Serafini et al. 2002).

Dietary and other environmental factors induce epigenetic alterations which may have important consequences for cancer development (Penn et al. 2009). Butyrate was the first food-derived substance shown to affect posttranslational modifications of histones through its action as an inhibitor of class 1 HDACs (Davie 2003; Kruh 1982; Vidali et al. 1978). More recently, a number of other dietary components have been identified which modulate the acetylation state of histones or affect the activities of HDACs and/or histone acetyl transferases [reviewed by Delage and Dashwood (2008)]. Proof of principle that dietary exposures may have lifelong consequences for epigenetic marks comes from recent studies of the adult offspring of women exposed to famine during pregnancy. Methylation of the imprinted gene insulin-like growth factor 2 was lower in adults (approximately 60 years of age) who were periconceptionally exposed to famine during the Dutch Hunger Winter of 1944–1945 (Heijmans et al. 2008). Interest in the effects of dietary compounds such as resveratrol which activate class III HDACs (sirtuins) is growing rapidly because of their demonstrable role in extending lifespan and in reducing, or delaying, age-related diseases including cancers (Baur 2010).

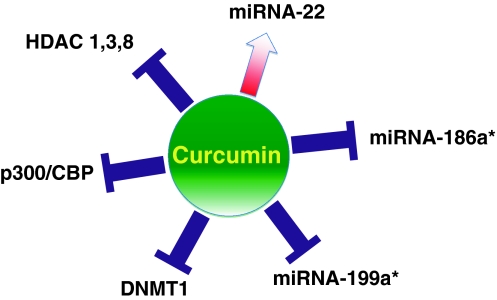

How curcumin exerts its powerful anticancer activities has been thoroughly investigated, and several mechanisms of action have been discovered. Although pharmacokinetic studies have shown that curcumin is present in much lower plasma concentration in humans than in vitro, numerous preclinical reports have demonstrated curcumin’s anticancer activity (Sharma et al. 2004; Cheng et al. 2001). One explanation for its activity in humans, even at lower concentrations, might be that curcumin exerts its biological activities through epigenetic modulation (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of epigenetic factors modulated by curcumin

Effect of curcumin on histone acetylation/deacetylation

Histone modifications are among the most important epigenetic changes, because it can alter gene expression and modify cancer risk (Gibbons 2005). Abnormal activity of both HATs and HDACs has been linked to the pathogenesis of cancer. HDACs are a class of enzymes that remove acetyl groups from an ε-N-acetyl lysine amino acid on a histone. Its action is opposite to that of HATs. HDAC enzymes do not bind to DNA directly but rather interact with DNA through multiprotein complexes that include corepressors and coactivators. At least 18 HDACs have been identified in humans, primarily occupying 4 classes based on homology with yeast deacetylases (Xu et al. 2007). HDAC inhibitors are being explored as cancer therapeutic compounds because of their ability to alter several cellular functions known to be deregulated in cancer cells (Davis and Ross 2007).

Recently, various studies have investigated the effect of curcumin on HDAC expression. Of these, Bora-Tatar et al. (2009) reported that among 33 carboxylic acid derivatives, curcumin was the most effective HDAC inhibitor, and that it was even more potent than valproic acid and sodium butyrate, which are well-known HDAC inhibitors. Another study revealed that HDAC 1, 3, and 8 protein levels were significantly decreased by curcumin, resulting in increased levels of acetylated histone H4 (Liu et al. 2005). Similarly, significant decreases in the amounts of HDAC1 and HDAC3 were detected by Chen et al. (2007) after treatment with curcumin.

By contrast, HDAC2, a critical component of corticosteroid anti-inflammatory action and impaired in lungs of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and by cigarette smoke extract, was restored by curcumin (Meja et al. 2008). Because of the differing effect of curcumin on the different subtypes of HDAC enzymes, further research is required to understand the mechanism of curcumin on HDAC expression.

HATs, enzymes that acetylate conserved lysine amino acids on histone proteins by transferring an acetyl group from acetyl CoA to form ε-N-acetyl lysine, are other important targets for dietary components. HATs include at least 25 members and are organized into 4 families based on primary structure homology (Lee and Workman 2007). Several studies have recently reported that curcumin is a potent HAT inhibitor. In 2004, Balasubramanyam et al. (2004) reported that curcumin is a specific inhibitor of p300/CREB-binding protein (CBP) HAT activity in vitro and in vivo but not of p300/CBP-associated factor. Furthermore, they showed that curcumin inhibited the p300-mediated acetylation of p53 in vivo and significantly repressed acetylation of HIV-Tat protein in vitro as well as proliferation of the virus (Balasubramanyam et al. 2004).

Another group that identified curcumin as a specific inhibitor of p300/CBP HAT activity in vitro and in vivo discovered that inhibition of p300 HAT activity by curcumin prevented also against heart failure in rats (Morimoto et al. 2008). Marcu et al. (2006) found that curcumin’s binding site on p300/CBP was specific and that binding led to a conformational change, resulting in a decrease in the binding efficiency of histones H3 and H4 and acetyl CoA.

It is well known that curcumin induces apoptosis of numerous cancer cell lines, but its mechanism may vary. Induction of apoptosis by curcumin in cervical cancer cells, for example, was associated with inhibition of histone and p53 acetylation through specific inhibition of p300/CBP (Balasubramanyam et al. 2004). For example, curcumin activated poly (ADP) ribose polymerase- and caspase-3–mediated apoptosis in brain glioma cells through induction of histone hypoacetylation (Kang et al. 2006).

Histones are acetylated and deacetylated on lysine residues, but HATs and HDACs can also modify the acetylation status of non-histone proteins (Sadoul et al. 2008). The regulation of transcription factors, effector proteins, molecular chaperones, and cytoskeletal proteins by acetylation/deacetylation is emerging as a significant post-translational regulatory mechanism (Glozak et al. 2005).

NF-κB, a pro-inflammatory transcription factor, undergoes acetylation before it activates hundreds of genes involved in different cellular processes (Chen et al. 2001; Gupta et al. 2010a). Acetylation of NF-κB takes place at multiple lysine residues with the p300/CBP acetyltransferases. Curcumin inhibited p300-mediated acetylation of RelA, an isoform of NF-κB, which attenuated interaction with IκBα, leading to decreased IκBα-dependent nuclear export of the complex through a chromosomal region maintenance-1–dependent pathway (Chen et al. 2001). In the same way, Yun et al. (2010) found that curcumin treatment significantly reduced HAT activity, p300 levels, and acetylated CBP/p300 gene expression and consequently suppressed NF-κB binding. Thus, curcumin’s ability to suppress p300/CBP HAT activity may be responsible, at least in part, for its potent NF-κB inhibitory activity.

Curcumin also inhibited the hypertrophy-induced acetylation and DNA-binding abilities of GATA4, a hypertrophy-responsive transcription factor, in rat cardiomyocytes, which indicates that inhibition of p300 HAT activity by curcumin may also provide a novel therapeutic strategy for heart failure in humans (Morimoto et al. 2008). Finally, curcumin also induced recontrolling of neural stem cell fates by decreasing histone H3 and H4 acetylation (Kang et al. 2006).

Since curcumin can modulate both HDAC and HAT, a common mechanism may be underlying. For example, oxidative stress can activate NF-κB through the activation of intrinsic HAT activity, resulting in the expression of pro-inflammatory mediators, but it can also inhibit HDAC activity (Rahman et al. 2004). As such, curcumin, a known antioxidant, may regulate both acetylation and deacetylation through the modulation of oxidative stress.

Effect of curcumin on DNA methylation

DNA methylation plays an essential role in regulating normal biological processes in addition to carcinogenesis (Esteller 2007). DNA methylation is a heritable modification of the DNA structure that does not alter the specific sequence of base pairs responsible for encoding the genome but that can directly inhibit gene expression (Das and Singal 2004). Two patterns of DNA methylation have been observed in cancer cells: global hypomethylation, or decreased methylation that can facilitate the expression of quiescent proto-oncogenes and prometastatic genes and promote tumor progression, or localized hypermethylation, an increased methylation at specific CpG islands within the gene promoter regions of specific genes, such as tumor suppressor genes, that can result in transcriptional silencing and an inability to control tumorigenesis (Ehrlich 2009). DNA methylation is regulated by DNA methyltransferases (DNMT1, DNMT3a, and DNMT3b) in the presence of S-adenosyl-methionine, which serves as a methyl donor for methylation of cytosine residues at the C-5 position to yield 5-methylcytosine (Herman and Baylin 2003).

Only a few reports have so far investigated the effect of curcumin on DNA methylation. Molecular docking of the interaction between curcumin and DNMT1 suggested that curcumin covalently blocks the catalytic thiolate of DNMT1 to exert its inhibitory effect on DNA methylation (Liu et al. 2009). However, a more recent study showed no curcumin-dependent demethylation, which suggested that curcumin has little or no pharmacologically relevant activity as a DNMT inhibitor (Medina-Franco et al. 2010). To clarify these contradictions, more research is urgently needed.

Given that 5-azacitidine and decitabine, two FDA-approved hypomethylating agents for treating myelodysplastic syndrome, have a demonstrated ability to sensitize cancer cells to chemotherapeutic agents, it would be worthwhile to explore whether the hypomethylation effect of curcumin can also induce cancer cell chemosensitization. Interestingly, a phase 1 trial with curcumin administered several days before docetaxel in patients with metastatic breast cancer resulted in 5 partial remissions and stable disease in 3 of 8 patients (Bayet-Robert et al. 2011). This unexpected high response might have resulted from the clever sequential delivery of these two agents, which capitalized on and maximized curcumin’s epigenetic activity for cancer treatment.

Effect of curcumin on miRNA expression

miRNAs, small noncoding regulatory RNAs, range in size from 17 to 25 nucleotides (Croce 2009) and are responsible for a reduced translation rate and/or increased degradation of mRNAs if aberrantly expressed. miRNAs play important roles in cell cycling, programmed cell death, cell differentiation, tumor development, invasion, metastasis, and angiogenesis (Negrini et al. 2007). To date, more than 500 human miRNA genes have been identified, and it is believed that at least 500 have yet to be discovered within the human genome (Bentwich et al. 2005). The specific function of most mammalian miRNAs is still unknown (Bentwich et al. 2005), but it is speculated that miRNAs could regulate ~30% of the human genome (Bartel 2004). Disturbances in the expression of miRNAs, processing of miRNA precursors, or mutations in the sequence of the miRNA, its precursor, or its target mRNA may have detrimental effects on cellular function and have been associated with cancer (Davis and Ross 2008). Some miRNAs could, for example, regulate the formation of cancer stem cells and the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) phenotype of cancer cells, which are typically drug resistant (Li et al. 2010).

It is known that curcumin regulates the expression of genes that are critically involved in the regulation of cellular signaling pathways, including NF-κB, Akt, MAPK, and other pathways (Mukhopadhyay et al. 2001; Sarkar and Li 2004). These signaling pathways could be regulated by miRNAs.

Recently, Sun et al. (2008) reported that curcumin altered miRNA expression in human pancreatic cancer cells. After 72 h of incubation, 11 miRNAs were significantly up-regulated and 18 were down-regulated by curcumin. Among these, miRNA-22 was the most significantly up-regulated and miRNA-199a* the most down-regulated. Those researchers also found that up-regulation of miR-22 expression by curcumin suppressed the expression of its target genes Sp1 and estrogen receptor 1 (Sun et al. 2008). These results suggest that curcumin could inhibit the proliferation of pancreatic cancer cells through the regulation of specific miRNAs. In addition, curcumin has been shown to promote apoptosis in A549/DDP multidrug-resistant human lung adenocarcinoma cells through an miRNA signaling pathway (Zhang et al. 2010). In these cells, curcumin significantly down-regulated the expression of miR-186* (Zhang et al. 2010). A major challenge for current miRNA studies is to identify the biologically relevant downstream targets that they regulate. In the study by Sun et al. (2008) at least 50 target genes for miRNA-22 were found, showing that a key effect of curcumin on pancreatic cancer cells could be mediated by epigenetic modulation of miRNAs.

In addition, a recent report showed that gemcitabine sensitivity can be induced in pancreatic cancer cells through modulation of miR-200 and miR-21 expression by curcumin (Ali et al. 2010). The miR-200 family has been shown to inhibit the EMT, the initiating step of metastasis, by maintaining the epithelial phenotype through direct targeting of the transcriptional repressors of E-cadherin, ZEB1, and ZEB2 (Korpal and Kang 2008). Therefore, targeting specific miRNAs could be a novel therapeutic approach for the treatment of cancers, especially by eliminating cancer stem cells or EMT-type cells that are typically drug resistant. In contrast, miR-21 is an oncomiR and is overexpressed in many tumors, thereby promoting cancer progression and metastasis. Curcumin treatment has been shown to reduce miR-21 promoter activity and expression in primary tumors by inhibiting AP-1 binding to the promoter and to induce expression of the tumor suppressor Pdcd4, a target of miR-21 (Mudduluru et al. 2011).

These novel findings suggest that the use of natural agents could open new avenues for the successful treatment of cancers, especially by combining conventional therapeutics with natural chemopreventive agents that are known to be nontoxic to humans (Li et al. 2010).

Curcumin and DNA binding

Curcumin’s antioxidant (Miquel et al. 2002), anti-inflammatory (Surh 1999), antimicrobial (Saleheen et al. 2002; Taher et al. 2003), and chemopreventive (Aggarwal et al. 2003) properties are attributed to various mechanisms, including an anti-angiogenic action; up-regulation of enzymes detoxifying carcinogens, such as glutathione S-transferase; inhibition of signal transduction pathways critical for tumor cell growth (e.g., NF-κB); suppression of cyclooxygenase expression; and neutralization of carcinogenic free radicals (Aggarwal et al. 2003; Chauhan 2002; Itokawa et al. 2008). However, the molecular basis of curcumin’s various therapeutic actions is far from established, perhaps because research has focused so far only on proteins as the potential macromolecular targets of curcumin and less on its ability to bind directly to the DNA and to modulate epigenetic mechanisms directly as a DNA binding agent.

In 2004, a direct interaction between curcumin and both natural and synthetic DNA duplexes was demonstrated by using circular dichroism and absorption spectroscopy techniques (Zsila et al. 2004). Evaluation of the spectral data and molecular modeling calculations suggested that curcumin binds to the minor groove of the double helix and that it is also a promising molecular probe to study biologically important pH- and cation-induced conformational polymorphisms of nucleic acids (Zsila et al. 2004). Based on these results, curcumin has to be considered as a new phenolic minor groove-binding agent, which may explain the observed anticancer potential and other pharmacological effects of this natural compound.

In the same way, Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) and UV analysis of the binding of curcumin to the DNA showed that curcumin can bind to the major and minor grooves of the DNA duplex, to RNA bases, and to the backbone phosphate group (Nafisi et al. 2009). No conformational changes were observed upon the interaction between curcumin and these biopolymers. Instead, Nafisi et al. (2009) found that curcumin binds to DNA through thymine O2 in the minor groove and through guanine and adenine N7 in the major groove, as well as to the backbone PO2 group. RNA binding occurs via uracil O2 and guanine and adenine N7 atoms as well as the backbone phosphate group. Interestingly, the interaction of curcumin was stronger with DNA than RNA.

Pentamidine, a diarylamidine antibiotic that is currently in clinical use for treatment of leishmaniasis, trypanosomiasis, and Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (Fairlamb 2003), has been suggested to interact directly with the pathogenic genome. It binds selectively to the minor groove of the DNA, similar to curcumin, and interferes with the normal functioning of the pathogen topoisomerases (Reddy et al. 1999; Neidle 2001; Bischoff and Hoffmann 2002). Interestingly, curcumin was also found to be effective against trypanosomiasis (Saleheen et al. 2002; Araujo and Leon 2001), which could be due to its binding ability to the minor groove of the DNA.

Effect of curcumin on transcription factors

Extensive research over the past five decades has indicated that curcumin reduces blood cholesterol levels; prevents low-density lipoprotein oxidation; inhibits platelet aggregation; suppresses thrombosis and myocardial infarction; suppresses symptoms associated with type II diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, and Alzheimer disease; inhibits HIV replication; suppresses tumor formation; enhances wound healing; protects against liver injury; increases bile secretion; protects against cataract formation; and protects against pulmonary toxicity and fibrosis (Shishodia et al. 2007). These divergent effects of curcumin seem to depend on its pleiotropic molecular effects, including the regulation of signal transduction pathways, and direct modulation of several enzymatic activities. Most of these signaling cascades lead to the activation of transcription factors.

Transcription factors are proteins that bind to DNA at a specific promoter or enhancer region, probably at histone tails, which are considered to be the platform for transcription factors (Fig. 1b), and thus regulate the expression of various genes. Hundreds of transcription factors with functionally different domains essential for DNA binding and activation have been identified and characterized in several organisms—some of the transcription factors are important targets for therapeutic intervention in several types of disease (Shishodia et al. 2007). For example, the transcription factors NF-κB, activator protein (AP)–1, and Signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) control the expression of genes that affect cell transformation, proliferation, cell survival, invasion, metastasis, adhesion, angiogenesis, and apoptosis (Aggarwal 2004; Aggarwal et al. 2009; Gupta et al. 2010b; Shishodia and Aggarwal 2004). Other transcription factors involved in cancer are early growth response-1 (Egr-1), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR- γ), electrophile response element (EpRE), β-catenin, NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), and androgen receptor (AR).

Our laboratory has previously shown that curcumin down-regulates the activation of NF-κB by various tumor promoters, including phorbol ester, tumor necrosis factor, hydrogen peroxide, and cigarette smoke (Shishodia et al. 2003; Singh and Aggarwal 1995). Curcumin-induced down-regulation of NF-κB was shown to be mediated through suppressed activation of IκBα kinase (IKK) (Shishodia et al. 2003; Jobin et al. 1999; Plummer et al. 1999). Moreover, curcumin can suppress constitutively active NF-κB in mantle cell lymphoma through the suppression of IKK (Shishodia et al. 2005). This leads to the down-regulation of cyclin D1, cyclooxygenase-2, and matrix metalloproteinase–9. Also, we found that curcumin suppressed the paclitaxel-induced NF-κB pathway in breast cancer cells and inhibits lung metastasis of human breast cancer in nude mice (Aggarwal et al. 2005).

AP-1 has also been closely linked with the proliferation and transformation of tumor cells (Karin et al. 1997). Curcumin has been shown to inhibit the activation of AP-1 induced by tumor promoters (Huang et al. 1991) and JNK activation by carcinogens (Chen and Tan 1998). Bierhaus et al. (1997) demonstrated that curcumin-induced inhibition of AP-1 was due to its direct interaction with the AP-1 DNA-binding motif.

Curcumin was also shown to modulate STATs, and constitutive STAT activation can be observed in a large number of tumors. Curcumin inhibited both NF-κB and STAT3 activation, leading to decreased expression of proteins involved in cell proliferation and apoptosis, such as Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, c-FLIP, XIAP, c-IAP1, survivin, c-Myc, and cyclin D1 (Mackenzie et al. 2008). The constitutive phosphorylation of STAT3 found in certain multiple myeloma cells was abrogated by treatment with curcumin (Bharti et al. 2003), and inhibition of STAT3 by curcumin led to the induction of apoptosis (Bharti et al. 2004). In addition, curcumin has been shown to modulate the Egr-1, PPAR-γ, EpRE, β-catenin, Nrf-2, and AR signaling pathways (Shishodia et al. 2003).

The evidence that curcumin modulates many important transcription factors, which are either constitutively expressed or overexpressed in cancer cells, might explain in part the molecular basis of the wide and complex effects of this phytochemical. The versatile chemical structure of curcumin enables it to interact with a large number of molecules inside the cell, leading to a variety of biological effects, such as modulation of the cell cycle, suppression of growth, induction of differentiation, up-regulation of proapoptotic factors, and inhibition of reactive oxygen species production.

Effect of other natural compounds on epigenetics

Evidence in the past decade has provided important clues that natural compounds present in plants and/or in the diet directly influence epigenetic mechanisms in humans (Table 1). Indeed, some dietary polyphenols may exert their chemopreventive effects in part by modulating various components of the epigenetic machinery in humans (Link et al. 2010).

Table 1.

Common HDAC, HAT and DNMT modulators derived from natural sources

| Natural inhibitor | References |

|---|---|

| HDAC | |

| Allyl mercaptan | Nian et al. (2008) |

| Amamistatin | Fennell and Miller (2007) |

| Apicidin | Darkin-Rattray et al. (1996) |

| Azumamide E | Maulucci et al. (2007) |

| Caffeic acid | Waldecker et al. (2008) |

| Chlamydocin | Brosch et al. (1995) |

| Chlorogenic acid | Bora-Tatar et al. (2009) |

| Cinnamic acid | Bora-Tatar et al. (2009) |

| Coumaric/hydroxycinnamic acid | Waldecker et al. (2008) |

| Curcumin | Bora-Tatar et al. (2009) |

| Depudecin | Kwon et al. (1998) |

| Diallyl disulfide | Lea et al. (1999) |

| Equol | Hong et al. (2004) |

| Flavone | Bontempo et al. (2007) |

| Genistein | Kikuno et al. (2008) |

| Histacin | Haggarty et al. (2003) |

| Isothiocyanates | Ma et al. (2006) |

| Largazole | Ying et al. (2008) |

| Pomiferin | Son et al. (2007) |

| Psammaplin | Pina et al. (2003) |

| SAHA (Vorinostat) | Richon et al. (1998) |

| S-allylmercaptocysteine | Lea et al. (2002) |

| Sulforaphane | Myzak et al. (2004) |

| Trapoxin | (Kijima et al. 1993) |

| Ursolic acid | Chen et al. (2009) |

| Zerumbone | Chung et al. (2008) |

| HAT | |

| Allspice | Lee et al. (2007) |

| Anarcardic acid | Balasubramanyam et al. (2003), Ghizzoni et al. (2010) |

| EGCG | Choi et al. (2009a) |

| Curcumin | Balasubramanyam et al. (2004), Marcu et al. (2006) |

| Gallic acid | Choi et al. (2009b) |

| Garcinol | Balasubramanyam et al. (2004) |

| Quercetin | Ruiz et al. (2007) |

| Sanguinarine | Selvi et al. (2009) |

| Plumbagin | Ravindra et al. (2009) |

| DNMT | |

| Genistein | Day et al. (2002) |

| EGCG | Fang et al. (2003) |

| Psammaplins | Pina et al. (2003) |

| Quercetin, fisetin, myricetin | Lee et al. (2005) |

| Caffeic acid | Lee and Zhu (2006) |

| Chlorogenic acid | Lee and Zhu (2006) |

| Curcumin | Moiseeva et al. (2007) |

| Parthenolide | Liu et al. (2009) |

| Mahanine | Sheikh et al. (2010) |

SAHA Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid, EGCG epigallocatechin gallate

EGCG, the ester of epigallocatechin and gallic acid and the major polyphenol in green tea, has been extensively studied as a potential demethylating agent. It has been hypothesized that generation of S-adenosyl-s-homocysteine, a potent inhibitor of DNA methylation, is one of the mechanisms for the demethylating properties of this compound. EGCG can form hydrogen bonds with different residues in the catalytic pocket of DNMT and thus act as a direct inhibitor of DNMT1 (Fang et al. 2003; Lee et al. 2005). EGCG has also been recently found to modulate miRNA expression in human hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells. Tsang and Kwok performed microarray analysis in this cell line after EGCG treatment and found that the compound modified the expression of 61 miRNAs (Tsang and Kwok 2010).

Choi et al. found that another compound, gallic acid—an organic acid found in gallnuts, sumac, witch hazel, tea leaves, oak bark, and other plants can inhibit p300-induced p65 acetylation, increase the level of cytosolic IκBα, prevent lipopolysaccharide (LPS)–induced p65 translocation to the nucleus, and suppress LPS-induced NF-κB activation in A549 lung cancer cells (Choi et al. 2009b). In addition, gallic acid inhibits the acetylation of p65 and LPS-induced serum levels of interleukin-6 in vivo.

Sanguinarine, an extract from several plants such as bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis) and in the root, stem, and leaves of the opium poppy, has been shown to induce conformational changes by interacting with chromatin (Selvi et al. 2009). Sanguinarine potently inhibited HAT activity in rat liver and cervical cancer cell lines, and this was associated with a dose-dependent decrease in H3/H4 acetylation.

Resveratrol, a natural compound found in the skin of red grapes and a constituent of red wine, is believed to play a significant role in the reduction of cardiovascular events (Artaud-Wild et al. 1993; Gupta et al. 2011). Multiple studies have shown that resveratrol can activate sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), a histone deacetylase, and inhibit p300 (Howitz et al. 2003; Gracia-Sancho et al. 2010). Sirtuins, the class III HDACs, are widely distributed and have been shown to regulate a variety of physiopathologic processes, such as inflammation, cellular senescence and aging, cellular apoptosis and proliferation, differentiation, metabolism, stem cell pluri-potency, and cell cycle regulation. Polyphenols, including not only resveratrol but also quercetin and catechins, have been shown to activate SIRT1, the best characterized of the seven mammalian sirtuins, SIRT1–7 (Kaeberlein et al. 2005; Borra et al. 2005; de Boer et al. 2006).

Similar to EGCG, resveratrol showed weak inhibition of DNMT activity in nuclear extracts from MCF7 cells (Paluszczak et al. 2010). In these cells, resveratrol improved the action of adenosine analogues to inhibit methylation and to increase expression of the retinoic acid receptor beta 2 gene (Stefanska et al. 2010). In addition, resveratrol decreased the levels of the miR-155 by up-regulating miR-663, an miRNA targeting JunB and JunD (Tili et al. 2010a), and modulated expression levels of miRNA target genes, such as tumor suppressors and effectors of the transforming growth factor–β signaling pathway, in SW480 cells (Tili et al. 2010b).

Anacardic acid, an active compound found in cashew nuts, has also been shown to be a specific HAT inhibitor (Balasubramanyam et al. 2003; Sun et al. 2006). Anacardic acid can inhibit p300, PCAF, and Tip60 HAT factors.

Garcinol, a highly cytotoxic polyisoprenylated benzophenone derived from garcinia fruit rinds, is also a potent inhibitor of different HATs, such as p300 and PCAF (Mai et al. 2006; Chandregowda et al. 2009; Balasubramanyam et al. 2004).

Plumbagin is another agent, derived from Plumbago rosea root extract, that has been found to potently inhibit HAT activity (Ravindra et al. 2009). Plumbagin derivatives without a hydroxyl group lost HAT inhibitory activity, indicating that the hydroxyl group is required for this activity.

Finally, genistein, one of the many phytoestrogens present in soybeans, has been recently studied as a demethylating agent. Genistein induced a dose-dependent inhibition of DNMT activity stronger than that of other soy isoflavones (biochanin A or diadzein) (Fang et al. 2005; Li et al. 2009). The continuously growing list of natural compounds (Table 1) that modulate epigenetic mechanisms shows the great interest in this exciting field and clinical trials performed with several of these compounds (Table 2) confirm their efficiency.

Table 2.

Clinical studies with curcumin and other natural compounds

| Disease | Dose/frequency | Patients | End point modulation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Curcumin | ||||

| Safety trials | ||||

| Phase 1 | 2,000 mg/day | 10 | Piperine enhanced bioavailability by 2,000% | Shoba et al. (1998) |

| Phase 1 | 500–12,000 mg/day × 90 days | 25 | Histologic improvement of precancerous lesions | Cheng et al. (2001) |

| Phase 1 | 500–12,000 mg/day | 24 | Safe, well-tolerated even at 12 g/day | Lao et al. (2006) |

| Efficacy trials | ||||

| Alzheimer’s disease | 1 g once daily, 4 g once daily | 36 | – | Baum et al. (2008) |

| Atherosclerosis | 10 mg; 2×/day × 28 days | 12 | Lowered LDL and ApoB, increased HDL and ApoA | Ramirez Bosca et al. (2000) |

| Cadaveric renal transplantation | 480 mg; 1–2/day × 30 days | 43 | Improved renal function, reduced neurotoxicity | Shoskes et al. (2005) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 500 mg/day × 7 days | 10 | Decreased serum lipid peroxidase (33%), increased HDL cholesterol (29%), decreased total serum cholesterol (12%) | Soni and Kuttan (1992) |

| Chronic anterior uveitis | 375 mg; 3×/day × 84 days | 32 | 86% decrease in chronic anterior uveitis | Lal et al. (1999) |

| Crohn’s disease | 360 mg; 3/day × 30 days; 4 for 60 days | 5 | Improved symptoms | Holt et al. (2005) |

| CRC | 36–180 mg/day × 120 days | 15 | Lowered GST | Sharma et al. (2001) |

| CRC | 450–3,600 mg/day × 120 days | 15 | Lowered inducible serum PGE2 levels | Sharma et al. (2004) |

| CRC | 450–3,600 mg/day × 7 days | 12 | Decreased M1G DNA adducts | Garcea et al. (2005) |

| Colon cancer | 10 g (n = 6) and 12 g (n = 6) | 12 | Pharmacokinetics | Vareed et al. (2008) |

| CRC, ACF | 2 g or 4 g/day for 30 days | 44 | A significant 40% reduction in ACF number occurred with the 4 g dose (P < 0.005), whereas ACF were not reduced in the 2 g group | Carroll et al. (2011) |

| External cancerous | 1% ointment for several months | 62 | Reduction in smell in 90% patients, reduction of itching in all cases, dry lesions in 70% patients, reduction in lesion size and pain in 10% patients | Kuttan et al. (1987) |

| FAP | 480 mg; 3/day × 180 days | 5 | Decrease in the number of polyps (60.4%), decrease in the size of polyps (50.9%) | Cruz-Correa et al. (2006) |

| H. pylori infection | 300 mg/day × 7 days | 25 | Significant improvement of dyspeptic symptoms | Di Mario et al. (2007) |

| HIV | 625 mg; 4×/day × 56 days | 40 | Well tolerated | James (1996) |

| IIOP | 375 mg; 3×/day × 180–660 days | 8 | Four patients recovered completely; one patient showed decrease in swelling, no recurrence | Lal et al. (2000) |

| Gall bladder function | 20 mg, single dose | 12 | Decreased gall bladder volume (29%) | Rasyid and Lelo (1999) |

| Gall bladder function | 20–80 mg, single dose | 12 | Decreased gall bladder volume (72%) | Rasyid et al. (2002) |

| ICF | – | 1,010 | Better MMSE score | Ng et al. (2006) |

| IBS | 72–144 mg/day × 56 days | 207 | Reduced symptoms | Bundy et al. (2004) |

| Liver metastasis | 450–3,600 mg/day × 7 day | 12 | Low bioavailability | Garcea et al. (2004) |

| Pancreatic cancer | 8 g by mouth daily every 2 months | 25 | Oral curcumin is well tolerated and, despite its limited absorption, has biological activity in some patients with pancreatic cancer | Dhillon et al. (2008) |

| Pancreatic cancer | 8 g | 21 | Safe and feasible in patients with pancreatic cancer | Kanai et al. (2010) |

| Postoperative inflammation | 400 mg; 3×/day × 5 days | 46 | Decrease in inflammation | Satoskar et al. (1986) |

| PIN | – | 24 | – | Rafailov et al. (2007) |

| Psoriasis | 1% curcumin gel | 40 | Decreased PhK2, TRR3, parakeratosis, and density of epidermal CD8+ T cells | Heng et al. (2000) |

| Psoriasis | 4.5 g/d | 18 | The response rate was low | Kurd et al. (2008) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 1,200 mg/day × 14 days | 18 | Improved symptoms | Deodhar et al. (1980) |

| Tropical pancreatitis | 500 mg/day × 42 days | 20 | Reduction in the erythrocyte MDA levels, increased erythrocyte GSH levels | Durgaprasad and Pai (2005) |

| Ulcerative proctitis | 550 mg; 2–3/day × 60 days | 5 | Improved symptoms | Holt et al. (2005) |

| Ulcerative colitis | 2,000 mg/day × 180 days | 89 | Low recurrence; improved symptoms | Hanai et al. (2006) |

| EGCG | ||||

| Safety trials | ||||

| Phase 1 | 200, 400, 600, and 800 mg | 20 | Systemic availability | Chow et al. (2001) |

| Efficacy trials | ||||

| OHT and OAG | 200 mg/day for 3 months | 36 | Influenced inner retinal function in eyes with early to moderately advanced glaucomatous | Falsini et al. (2009) |

| EE and fat oxidation | Catechins: 493.8–684 mg | 15 | Small acute effects on EE and fat oxidation | Gregersen et al. (2009) |

| Influenza infection | Catechins: 200 μg/mL 3/day for 3 months | 124 | Influenza infection was significantly lowered | Yamada et al. (2006) |

| Inhalation of MRSA | 3.7 mg/mL 3/day for 7 days | 72 | Reduced the MRSA count in sputum | Yamada et al. (2006) |

| Resveratrol | ||||

| Safety trial | ||||

| Pharmaco-kinetics | 0.5, 1, 2.5, or 5 g daily for 29 days | 40 | 2.5 and 5 g doses caused mild to moderate gastrointestinal symptoms | Brown et al. (2010) |

| Phase 1 | 0.5, 1, 2.5, or 5 g | 10 | High systemic levels of resveratrol conjugate metabolites | Boocock et al. (2007) |

| Efficacy trials | ||||

| Cerebral blood flow | 250 and 500 mg | 22 | Modulated cerebral blood flow variables | Kennedy et al. (2010) |

| Drug- and carcinogen-metabolizing enzymes | 1 g of resveratrol once daily for 4 weeks | 42 | Modulated enzyme systems involved in carcinogen activation and detoxification | Chow et al. (2010) |

| CRC | 8 daily doses of 0.5 or 1 g | 20 | Reduced tumor cell proliferation by 5% | Patel et al. (2010) |

| Genistein | ||||

| Safety trial | ||||

| Phase 1 | 600 mg/day for 84 days | 18 | Safe and well tolerated | Pop et al. (2008) |

| Pharmaco-kinetics | 2, 4, 8, or 16 mg/kg | 24 | Minimal clinical toxicity | Bloedon et al. (2002) |

| Efficacy trials | ||||

| Endometrial hyperplasia | 54 mg/day for 6 months | 56 | Useful for the management of endometrial hyperplasia | Bitto et al. (2010) |

| Prostate cancer | 450 mg daily for 6 months | 53 | Did not lower PSA levels | deVere White et al. (2010) |

| CV risk | 54 mg/day for 24 months | 198 | Favorable effects on both glycemic control and some cardiovascular risk markers | Atteritano et al. (2007) |

| Coronary heart disease | 71 mg | 33 | Neither harmful nor beneficial | Webb et al. (2008) |

| Bone metabolism | – | 208 | Protective against bone loss | Kritz-Silverstein and Goodman-Gruen (2002) |

| Asthma | – | 1,033 | Better lung function | Smith et al. (2004) |

ACF Aberrant crypt foci, CRC colorectal cancer, CV cardiovascular, EE energy expenditure, EGCG epigallocatechin, FAP familial adenomatous polyposis, GSH glutathione, GST glutathione S-transferase, HDL high-density lipoprotein, HIV human immunodeficiency virus, IBS irritable bowel syndrome, ICF improved cognitive function, IIOP idiopathic inflammatory orbital pseudotumors, LDL low-density lipoprotein, MDA malondialdehyde, MMSE mini-mental state examination, MRSA methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, OAG open-angle glaucoma, OHT ocular hyper-damage tension, PGE2 prostaglandin E2, PhK2 phosphorylase kinase 2, PIN prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia, PSA prostate-specific antigen, TRR3 transferrin receptor 3

Conclusion

Experimental evidence accumulated in the recent years clearly supports the idea that dietary nutraceuticals such as curcumin have great potential as epigenetic agents. Unlike genetic changes, epigenetic changes can be modified by the environment, diet, or pharmacological intervention. This characteristic has increased enthusiasm for developing therapeutic strategies by targeting the various epigenetic factors, such as HDAC, HAT, DNMTs, and miRNAs, by dietary polyphenols such as curcumin (Fig. 2). Further investigation of phytochemicals as epigenetic agents is, however, urgently needed to fully explore the potential of these nutraceuticals in the treatment of cancer and other diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Virginia Mohlere for carefully editing this article. This work was supported by MD Anderson’s Cancer Center Support Grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH CA-16672), a program project grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH CA-124787-01A2), and a grant from the Center for Targeted Therapy at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, where Dr. Aggarwal is the Ransom Horne, Jr., Professor of Cancer Research. Simone Reuter was supported by a grant from the Fonds National de la Recherche Luxembourg (PDR-08-017).

References

- Aggarwal BB. Nuclear factor-kappaB: the enemy within. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:203–208. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal BB, Sung B. Pharmacological basis for the role of curcumin in chronic diseases: an age-old spice with modern targets. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009;30:85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal BB, Kumar A, Bharti AC. Anticancer potential of curcumin: preclinical and clinical studies. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:363–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal BB, Shishodia S, Takada Y, Banerjee S, Newman RA, Bueso-Ramos CE, et al. Curcumin suppresses the paclitaxel-induced nuclear factor-kappaB pathway in breast cancer cells and inhibits lung metastasis of human breast cancer in nude mice. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:7490–7498. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal BB, Kunnumakkara AB, Harikumar KB, Gupta SR, Tharakan ST, Koca C, et al. Signal transducer and activator of transcription-3, inflammation, and cancer: how intimate is the relationship? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1171:59–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04911.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali S, Ahmad A, Banerjee S, Padhye S, Dominiak K, Schaffert JM, et al. Gemcitabine sensitivity can be induced in pancreatic cancer cells through modulation of miR-200 and miR-21 expression by curcumin or its analogue CDF. Cancer Res. 2010;70:3606–3617. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Araujo CC, Leon LL. Biological activities of Curcuma longa L. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2001;96:723–728. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762001000500026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artaud-Wild SM, Connor SL, Sexton G, Connor WE. Differences in coronary mortality can be explained by differences in cholesterol and saturated fat intakes in 40 countries but not in France and Finland. A paradox. Circulation. 1993;88:2771–2779. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.6.2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atteritano M, Marini H, Minutoli L, Polito F, Bitto A, Altavilla D, et al. Effects of the phytoestrogen genistein on some predictors of cardiovascular risk in osteopenic, postmenopausal women: a two-year randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:3068–3075. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanyam K, Swaminathan V, Ranganathan A, Kundu TK. Small molecule modulators of histone acetyltransferase p300. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:19134–19140. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301580200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanyam K, Varier RA, Altaf M, Swaminathan V, Siddappa NB, Ranga U, et al. Curcumin, a novel p300/CREB-binding protein-specific inhibitor of acetyltransferase, represses the acetylation of histone/nonhistone proteins and histone acetyltransferase-dependent chromatin transcription. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:51163–51171. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409024200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanyam K, Altaf M, Varier RA, Swaminathan V, Ravindran A, Sadhale PP, et al. Polyisoprenylated benzophenone, garcinol, a natural histone acetyltransferase inhibitor, represses chromatin transcription and alters global gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:33716–33726. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402839200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum L, Lam CW, Cheung SK, Kwok T, Lui V, Tsoh J, et al. Six-month randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, pilot clinical trial of curcumin in patients with Alzheimer disease. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28:110–113. doi: 10.1097/jcp.0b013e318160862c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baur JA. Resveratrol, sirtuins, and the promise of a DR mimetic. Mech Ageing Dev. 2010;131:261–269. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayet-Robert M, Kwiatkowski F, Leheurteur M, Gachon F, Planchat E, Abrial C, et al. Phase I dose escalation trial of docetaxel plus curcumin in patients with advanced and metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;9:8–14. doi: 10.4161/cbt.9.1.10392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentwich I, Avniel A, Karov Y, Aharonov R, Gilad S, Barad O, et al. Identification of hundreds of conserved and nonconserved human microRNAs. Nat Genet. 2005;37:766–770. doi: 10.1038/ng1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharti AC, Donato N, Aggarwal BB. Curcumin (diferuloylmethane) inhibits constitutive and IL-6-inducible STAT3 phosphorylation in human multiple myeloma cells. J Immunol. 2003;171:3863–3871. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.7.3863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharti AC, Shishodia S, Reuben JM, Weber D, Alexanian R, Raj-Vadhan S, et al. Nuclear factor-kappaB and STAT3 are constitutively active in CD138 + cells derived from multiple myeloma patients, and suppression of these transcription factors leads to apoptosis. Blood. 2004;103:3175–3184. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierhaus A, Zhang Y, Quehenberger P, Luther T, Haase M, Muller M, et al. The dietary pigment curcumin reduces endothelial tissue factor gene expression by inhibiting binding of AP-1 to the DNA and activation of NF-kappa B. Thromb Haemost. 1997;77:772–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff G, Hoffmann S. DNA-binding of drugs used in medicinal therapies. Curr Med Chem. 2002;9:312–348. doi: 10.2174/0929867023371085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitto A, Granese R, Triolo O, Villari D, Maisano D, Giordano D, et al. Genistein aglycone: a new therapeutic approach to reduce endometrial hyperplasia. Phytomedicine. 2010;17:844–850. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2010.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloedon LT, Jeffcoat AR, Lopaczynski W, Schell MJ, Black TM, Dix KJ, et al. Safety and pharmacokinetics of purified soy isoflavones: single-dose administration to postmenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:1126–1137. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.5.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bontempo P, Mita L, Miceli M, Doto A, Nebbioso A, Bellis F, et al. Feijoa sellowiana derived natural Flavone exerts anti-cancer action displaying HDAC inhibitory activities. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:1902–1914. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boocock DJ, Faust GE, Patel KR, Schinas AM, Brown VA, Ducharme MP, et al. Phase I dose escalation pharmacokinetic study in healthy volunteers of resveratrol, a potential cancer chemopreventive agent. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:1246–1252. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bora-Tatar G, Dayangac-Erden D, Demir AS, Dalkara S, Yelekci K, Erdem-Yurter H. Molecular modifications on carboxylic acid derivatives as potent histone deacetylase inhibitors: Activity and docking studies. Bioorg Med Chem. 2009;17:5219–5228. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borra MT, Smith BC, Denu JM. Mechanism of human SIRT1 activation by resveratrol. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17187–17195. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501250200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosch G, Ransom R, Lechner T, Walton JD, Loidl P. Inhibition of maize histone deacetylases by HC toxin, the host-selective toxin of Cochliobolus carbonum. Plant Cell. 1995;7:1941–1950. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.11.1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown VA, Patel KR, Viskaduraki M, Crowell JA, Perloff M, Booth TD, et al. Repeat dose study of the cancer chemopreventive agent resveratrol in healthy volunteers: safety, pharmacokinetics, and effect on the insulin-like growth factor axis. Cancer Res. 2010;70:9003–9011. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bundy R, Walker AF, Middleton RW, Booth J. Turmeric extract may improve irritable bowel syndrome symptomology in otherwise healthy adults: a pilot study. J Altern Complement Med. 2004;10:1015–1018. doi: 10.1089/acm.2004.10.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll RE, Benya RV, Turgeon DK, Vareed S, Neuman M, Rodriguez L, et al. Phase IIa Clinical Trial of Curcumin for the Prevention of Colorectal Neoplasia. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;4:354–364. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandregowda V, Kush A, Reddy GC. Synthesis of benzamide derivatives of anacardic acid and their cytotoxic activity. Eur J Med Chem. 2009;44:2711–2719. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan DP. Chemotherapeutic potential of curcumin for colorectal cancer. Curr Pharm Des. 2002;8:1695–1706. doi: 10.2174/1381612023394016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YR, Tan TH. Inhibition of the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling pathway by curcumin. Oncogene. 1998;17:173–178. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Fischle W, Verdin E, Greene WC. Duration of nuclear NF-kappaB action regulated by reversible acetylation. Science. 2001;293:1653–1657. doi: 10.1126/science.1062374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Shu W, Chen W, Wu Q, Liu H, Cui G. Curcumin, both histone deacetylase and p300/CBP-specific inhibitor, represses the activity of nuclear factor kappa B and Notch 1 in Raji cells. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;101:427–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2007.00142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen IH, Lu MC, Du YC, Yen MH, Wu CC, Chen YH, et al. Cytotoxic triterpenoids from the stems of Microtropis japonica. J Nat Prod. 2009;72:1231–1236. doi: 10.1021/np800694b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng AL, Hsu CH, Lin JK, Hsu MM, Ho YF, Shen TS, et al. Phase I clinical trial of curcumin, a chemopreventive agent, in patients with high-risk or pre-malignant lesions. Anticancer Res. 2001;21:2895–2900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi KC, Jung MG, Lee YH, Yoon JC, Kwon SH, Kang HB, et al. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate, a histone acetyltransferase inhibitor, inhibits EBV-induced B lymphocyte transformation via suppression of RelA acetylation. Cancer Res. 2009;69:583–592. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi KC, Lee YH, Jung MG, Kwon SH, Kim MJ, Jun WJ, et al. Gallic acid suppresses lipopolysaccharide-induced nuclear factor-kappaB signaling by preventing RelA acetylation in A549 lung cancer cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7:2011–2021. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow HH, Cai Y, Alberts DS, Hakim I, Dorr R, Shahi F, et al. Phase I pharmacokinetic study of tea polyphenols following single-dose administration of epigallocatechin gallate and polyphenon E. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10:53–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow HH, Garland LL, Hsu CH, Vining DR, Chew WM, Miller JA, et al. Resveratrol modulates drug- and carcinogen-metabolizing enzymes in a healthy volunteer study. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2010;3:1168–1175. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung IM, Kim MY, Park WH, Moon HI. Histone deacetylase inhibitors from the rhizomes of Zingiber zerumbet. Pharmazie. 2008;63:774–776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croce CM. Causes and consequences of microRNA dysregulation in cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:704–714. doi: 10.1038/nrg2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Correa M, Shoskes DA, Sanchez P, Zhao R, Hylind LM, Wexner SD, et al. Combination treatment with curcumin and quercetin of adenomas in familial adenomatous polyposis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1035–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darkin-Rattray SJ, Gurnett AM, Myers RW, Dulski PM, Crumley TM, Allocco JJ, et al. Apicidin: a novel antiprotozoal agent that inhibits parasite histone deacetylase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:13143–13147. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das PM, Singal R. DNA methylation and cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4632–4642. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davie JR. Inhibition of histone deacetylase activity by butyrate. J Nutr. 2003;133:2485S–2493S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.7.2485S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis CD, Ross SA. Dietary components impact histone modifications and cancer risk. Nutr Rev. 2007;65:88–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2007.tb00285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis CD, Ross SA. Evidence for dietary regulation of microRNA expression in cancer cells. Nutr Rev. 2008;66:477–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day JK, Bauer AM, DesBordes C, Zhuang Y, Kim BE, Newton LG, et al. Genistein alters methylation patterns in mice. J Nutr. 2002;132:2419S–2423S. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.8.2419S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boer VC, Goffau MC, Arts IC, Hollman PC, Keijer J. SIRT1 stimulation by polyphenols is affected by their stability and metabolism. Mech Ageing Dev. 2006;127:618–627. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delage B, Dashwood RH. Dietary manipulation of histone structure and function. Annu Rev Nutr. 2008;28:347–366. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.28.061807.155354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deodhar SD, Sethi R, Srimal RC. Preliminary study on antirheumatic activity of curcumin (diferuloyl methane) Indian J Med Res. 1980;71:632–634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devasagayam TP, Tilak JC, Boloor KK, Sane KS, Ghaskadbi SS, Lele RD. Free radicals and antioxidants in human health: current status and future prospects. J Assoc Physicians India. 2004;52:794–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- deVere White RW, Tsodikov A, Stapp EC, Soares SE, Fujii H, Hackman RM. Effects of a high dose, aglycone-rich soy extract on prostate-specific antigen and serum isoflavone concentrations in men with localized prostate cancer. Nutr Cancer. 2010;62:1036–1043. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2010.492085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon N, Aggarwal BB, Newman RA, Wolff RA, Kunnumakkara AB, Abbruzzese JL, et al. Phase II trial of curcumin in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4491–4499. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Mario F, Cavallaro LG, Nouvenne A, Stefani N, Cavestro GM, Iori V, et al. A curcumin-based 1-week triple therapy for eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection: something to learn from failure? Helicobacter. 2007;12:238–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durgaprasad S, Pai CG. Vasanthkumar, Alvres JF, Namitha S. A pilot study of the antioxidant effect of curcumin in tropical pancreatitis. Indian J Med Res. 2005;122:315–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich M. DNA hypomethylation in cancer cells. Epigenomics. 2009;1:239–259. doi: 10.2217/epi.09.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteller M. Cancer epigenomics: DNA methylomes and histone-modification maps. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:286–298. doi: 10.1038/nrg2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairlamb AH. Chemotherapy of human African trypanosomiasis: current and future prospects. Trends Parasitol. 2003;19:488–494. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falsini B, Marangoni D, Salgarello T, Stifano G, Montrone L, Di Landro S, et al. Effect of epigallocatechin-gallate on inner retinal function in ocular hypertension and glaucoma: a short-term study by pattern electroretinogram. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2009;247:1223–1233. doi: 10.1007/s00417-009-1064-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang MZ, Wang Y, Ai N, Hou Z, Sun Y, Lu H, et al. Tea polyphenol (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits DNA methyltransferase and reactivates methylation-silenced genes in cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2003;63:7563–7570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang MZ, Chen D, Sun Y, Jin Z, Christman JK, Yang CS. Reversal of hypermethylation and reactivation of p16INK4a, RARbeta, and MGMT genes by genistein and other isoflavones from soy. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:7033–7041. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fennell KA, Miller MJ. Syntheses of amamistatin fragments and determination of their HDAC and antitumor activity. Org Lett. 2007;9:1683–1685. doi: 10.1021/ol070382e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcea G, Jones DJ, Singh R, Dennison AR, Farmer PB, Sharma RA, et al. Detection of curcumin and its metabolites in hepatic tissue and portal blood of patients following oral administration. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:1011–1015. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcea G, Berry DP, Jones DJ, Singh R, Dennison AR, Farmer PB, et al. Consumption of the putative chemopreventive agent curcumin by cancer patients: assessment of curcumin levels in the colorectum and their pharmacodynamic consequences. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:120–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghizzoni M, Boltjes A, Graaf C, Haisma HJ, Dekker FJ. Improved inhibition of the histone acetyltransferase PCAF by an anacardic acid derivative. Bioorg Med Chem. 2010;18:5826–5834. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.06.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons RJ. Histone modifying and chromatin remodelling enzymes in cancer and dysplastic syndromes. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14(1):R85–R92. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glozak MA, Sengupta N, Zhang X, Seto E. Acetylation and deacetylation of non-histone proteins. Gene. 2005;363:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gracia-Sancho J, Villarreal G, Jr, Zhang Y, Garcia-Cardena G. Activation of SIRT1 by resveratrol induces KLF2 expression conferring an endothelial vasoprotective phenotype. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;85:514–519. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregersen NT, Bitz C, Krog-Mikkelsen I, Hels O, Kovacs EM, Rycroft JA, et al. Effect of moderate intakes of different tea catechins and caffeine on acute measures of energy metabolism under sedentary conditions. Br J Nutr. 2009;102:1187–1194. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509371779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta SC, Sundaram C, Reuter S, Aggarwal BB. Inhibiting NF-kappaB activation by small molecules as a therapeutic strategy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1799:775–787. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta SC, Kim JH, Prasad S, Aggarwal BB. Regulation of survival, proliferation, invasion, angiogenesis, and metastasis of tumor cells through modulation of inflammatory pathways by nutraceuticals. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2010;29:405–434. doi: 10.1007/s10555-010-9235-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta SC, Kannappan R, Reuter S, Kim JH, Aggarwal BB. Chemosensitization of tumors by resveratrol. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1215:150–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05852.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haggarty SJ, Koeller KM, Wong JC, Butcher RA, Schreiber SL. Multidimensional chemical genetic analysis of diversity-oriented synthesis-derived deacetylase inhibitors using cell-based assays. Chem Biol. 2003;10:383–396. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(03)00095-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanai H, Iida T, Takeuchi K, Watanabe F, Maruyama Y, Andoh A, et al. Curcumin maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis: randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1502–1506. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heijmans BT, Tobi EW, Stein AD, Putter H, Blauw GJ, Susser ES, et al. Persistent epigenetic differences associated with prenatal exposure to famine in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:17046–17049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806560105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heng MC, Song MK, Harker J, Heng MK. Drug-induced suppression of phosphorylase kinase activity correlates with resolution of psoriasis as assessed by clinical, histological and immunohistochemical parameters. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:937–949. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman JG, Baylin SB. Gene silencing in cancer in association with promoter hypermethylation. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2042–2054. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra023075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt PR, Katz S, Kirshoff R. Curcumin therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: a pilot study. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:2191–2193. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-3032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong T, Nakagawa T, Pan W, Kim MY, Kraus WL, Ikehara T, et al. Isoflavones stimulate estrogen receptor-mediated core histone acetylation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;317:259–264. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howitz KT, Bitterman KJ, Cohen HY, Lamming DW, Lavu S, Wood JG, et al. Small molecule activators of sirtuins extend Saccharomyces cerevisiae lifespan. Nature. 2003;425:191–196. doi: 10.1038/nature01960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang MT, Lysz T, Ferraro T, Abidi TF, Laskin JD, Conney AH. Inhibitory effects of curcumin on in vitro lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase activities in mouse epidermis. Cancer Res. 1991;51:813–819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itokawa H, Shi Q, Akiyama T, Morris-Natschke SL, Lee KH. Recent advances in the investigation of curcuminoids. Chin Med. 2008;3:11. doi: 10.1186/1749-8546-3-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James JS. Curcumin: clinical trial finds no antiviral effect. AIDS Treat News. 1996;242:1–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobin C, Bradham CA, Russo MP, Juma B, Narula AS, Brenner DA, et al. Curcumin blocks cytokine-mediated NF-kappa B activation and proinflammatory gene expression by inhibiting inhibitory factor I-kappa B kinase activity. J Immunol. 1999;163:3474–3483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaeberlein M, McDonagh T, Heltweg B, Hixon J, Westman EA, Caldwell SD, et al. Substrate-specific activation of sirtuins by resveratrol. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17038–17045. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500655200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai M, Yoshimura K, Asada M, Imaizumi A, Suzuki C, Matsumoto S et al (2010) A phase I/II study of gemcitabine-based chemotherapy plus curcumin for patients with gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kang SK, Cha SH, Jeon HG. Curcumin-induced histone hypoacetylation enhances caspase-3-dependent glioma cell death and neurogenesis of neural progenitor cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2006;15:165–174. doi: 10.1089/scd.2006.15.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin M, Liu Z, Zandi E. AP-1 function and regulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:240–246. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy DO, Wightman EL, Reay JL, Lietz G, Okello EJ, Wilde A, et al. Effects of resveratrol on cerebral blood flow variables and cognitive performance in humans: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover investigation. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1590–1607. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kijima M, Yoshida M, Sugita K, Horinouchi S, Beppu T. Trapoxin, an antitumor cyclic tetrapeptide, is an irreversible inhibitor of mammalian histone deacetylase. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:22429–22435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuno N, Shiina H, Urakami S, Kawamoto K, Hirata H, Tanaka Y, et al. Genistein mediated histone acetylation and demethylation activates tumor suppressor genes in prostate cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:552–560. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korpal M, Kang Y. The emerging role of miR-200 family of microRNAs in epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer metastasis. RNA Biol. 2008;5:115–119. doi: 10.4161/rna.5.3.6558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kritz-Silverstein D, Goodman-Gruen DL. Usual dietary isoflavone intake, bone mineral density, and bone metabolism in postmenopausal women. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2002;11:69–78. doi: 10.1089/152460902753473480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruh J. Effects of sodium butyrate, a new pharmacological agent, on cells in culture. Mol Cell Biochem. 1982;42:65–82. doi: 10.1007/BF00222695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurd SK, Smith N, VanVoorhees A, Troxel AB, Badmaev V, Seykora JT, et al. Oral curcumin in the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis vulgaris: A prospective clinical trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:625–631. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuttan R, Sudheeran PC, Josph CD. Turmeric and curcumin as topical agents in cancer therapy. Tumori. 1987;73:29–31. doi: 10.1177/030089168707300105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon HJ, Owa T, Hassig CA, Shimada J, Schreiber SL. Depudecin induces morphological reversion of transformed fibroblasts via the inhibition of histone deacetylase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:3356–3361. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lal B, Kapoor AK, Asthana OP, Agrawal PK, Prasad R, Kumar P, et al. Efficacy of curcumin in the management of chronic anterior uveitis. Phytother Res. 1999;13:318–322. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1573(199906)13:4<318::AID-PTR445>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lal B, Kapoor AK, Agrawal PK, Asthana OP, Srimal RC. Role of curcumin in idiopathic inflammatory orbital pseudotumours. Phytother Res. 2000;14:443–447. doi: 10.1002/1099-1573(200009)14:6<443::aid-ptr619>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lao CD, Ruffin MTt, Normolle D, Heath DD, Murray SI, Bailey JM, et al. Dose escalation of a curcuminoid formulation. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2006;6:10. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-6-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lea MA, Randolph VM, Patel M. Increased acetylation of histones induced by diallyl disulfide and structurally related molecules. Int J Oncol. 1999;15:347–352. doi: 10.3892/ijo.15.2.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lea MA, Rasheed M, Randolph VM, Khan F, Shareef A, desBordes C. Induction of histone acetylation and inhibition of growth of mouse erythroleukemia cells by S-allylmercaptocysteine. Nutr Cancer. 2002;43:90–102. doi: 10.1207/S15327914NC431_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KK, Workman JL. Histone acetyltransferase complexes: one size doesn’t fit all. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:284–295. doi: 10.1038/nrm2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee WJ, Zhu BT. Inhibition of DNA methylation by caffeic acid and chlorogenic acid, two common catechol-containing coffee polyphenols. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:269–277. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee WJ, Shim JY, Zhu BT. Mechanisms for the inhibition of DNA methyltransferases by tea catechins and bioflavonoids. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;68:1018–1030. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.008367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YH, Hong SW, Jun W, Cho HY, Kim HC, Jung MG, et al. Anti-histone acetyltransferase activity from allspice extracts inhibits androgen receptor-dependent prostate cancer cell growth. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2007;71:2712–2719. doi: 10.1271/bbb.70306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Liu L, Andrews LG, Tollefsbol TO. Genistein depletes telomerase activity through cross-talk between genetic and epigenetic mechanisms. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:286–296. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Kong D, Wang Z, Sarkar FH. Regulation of microRNAs by natural agents: an emerging field in chemoprevention and chemotherapy research. Pharm Res. 2010;27:1027–1041. doi: 10.1007/s11095-010-0105-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link A, Balaguer F, Goel A (2010) Cancer chemoprevention by dietary polyphenols: Promising role for epigenetics. Biochem Pharmacol 80:1771–1792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Liu HL, Chen Y, Cui GH, Zhou JF. Curcumin, a potent anti-tumor reagent, is a novel histone deacetylase inhibitor regulating B-NHL cell line Raji proliferation. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2005;26:603–609. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2005.00081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Xie Z, Jones W, Pavlovicz RE, Liu S, Yu J, et al. Curcumin is a potent DNA hypomethylation agent. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009;19:706–709. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Liu S, Xie Z, Pavlovicz RE, Wu J, Chen P, et al. Modulation of DNA methylation by a sesquiterpene lactone parthenolide. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;329:505–514. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.147934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Fang Y, Beklemisheva A, Dai W, Feng J, Ahmed T, et al. Phenylhexyl isothiocyanate inhibits histone deacetylases and remodels chromatins to induce growth arrest in human leukemia cells. Int J Oncol. 2006;28:1287–1293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie GG, Queisser N, Wolfson ML, Fraga CG, Adamo AM, Oteiza PI. Curcumin induces cell-arrest and apoptosis in association with the inhibition of constitutively active NF-kappaB and STAT3 pathways in Hodgkin’s lymphoma cells. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:56–65. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai A, Rotili D, Tarantino D, Ornaghi P, Tosi F, Vicidomini C, et al. Small-molecule inhibitors of histone acetyltransferase activity: identification and biological properties. J Med Chem. 2006;49:6897–6907. doi: 10.1021/jm060601m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcu MG, Jung YJ, Lee S, Chung EJ, Lee MJ, Trepel J, et al. Curcumin is an inhibitor of p300 histone acetylatransferase. Med Chem. 2006;2:169–174. doi: 10.2174/157340606776056133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maulucci N, Chini MG, Micco SD, Izzo I, Cafaro E, Russo A, et al. Molecular insights into azumamide e histone deacetylases inhibitory activity. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:3007–3012. doi: 10.1021/ja0686256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Franco JL, Lopez-Vallejo F, Kuck D, Lyko F (2010) Natural products as DNA methyltransferase inhibitors: a computer-aided discovery approach. Mol Divers [DOI] [PubMed]

- Meja KK, Rajendrasozhan S, Adenuga D, Biswas SK, Sundar IK, Spooner G, et al. Curcumin restores corticosteroid function in monocytes exposed to oxidants by maintaining HDAC2. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;39:312–323. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0012OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miquel J, Bernd A, Sempere JM, Diaz-Alperi J, Ramirez A. The curcuma antioxidants: pharmacological effects and prospects for future clinical use. A review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2002;34:37–46. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4943(01)00194-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moiseeva EP, Almeida GM, Jones GD, Manson MM. Extended treatment with physiologic concentrations of dietary phytochemicals results in altered gene expression, reduced growth, and apoptosis of cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:3071–3079. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto T, Sunagawa Y, Kawamura T, Takaya T, Wada H, Nagasawa A, et al. The dietary compound curcumin inhibits p300 histone acetyltransferase activity and prevents heart failure in rats. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:868–878. doi: 10.1172/JCI33160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mudduluru G, George-William JN, Muppala S, Asangani IA, Regalla K, Nelson LD et al (2011) Curcumin regulates miR-21 expression and inhibits invasion and metastasis in colorectal cancer. Biosci Rep 31:185–197 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mukhopadhyay A, Bueso-Ramos C, Chatterjee D, Pantazis P, Aggarwal BB. Curcumin downregulates cell survival mechanisms in human prostate cancer cell lines. Oncogene. 2001;20:7597–7609. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myzak MC, Karplus PA, Chung FL, Dashwood RH. A novel mechanism of chemoprotection by sulforaphane: inhibition of histone deacetylase. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5767–5774. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nafisi S, Adelzadeh M, Norouzi Z, Sarbolouki MN. Curcumin binding to DNA and RNA. DNA Cell Biol. 2009;28:201–208. doi: 10.1089/dna.2008.0840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negrini M, Ferracin M, Sabbioni S, Croce CM. MicroRNAs in human cancer: from research to therapy. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:1833–1840. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neidle S. DNA minor-groove recognition by small molecules. Nat Prod Rep. 2001;18:291–309. doi: 10.1039/a705982e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng TP, Chiam PC, Lee T, Chua HC, Lim L, Kua EH. Curry consumption and cognitive function in the elderly. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164:898–906. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nian H, Delage B, Pinto JT, Dashwood RH. Allyl mercaptan, a garlic-derived organosulfur compound, inhibits histone deacetylase and enhances Sp3 binding on the P21WAF1 promoter. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:1816–1824. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paluszczak J, Krajka-Kuzniak V, Baer-Dubowska W. The effect of dietary polyphenols on the epigenetic regulation of gene expression in MCF7 breast cancer cells. Toxicol Lett. 2010;192:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel KR, Brown VA, Jones DJ, Britton RG, Hemingway D, Miller AS, et al. Clinical pharmacology of resveratrol and its metabolites in colorectal cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2010;70:7392–7409. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penn L, White M, Oldroyd J, Walker M, Alberti KG, Mathers JC. Prevention of type 2 diabetes in adults with impaired glucose tolerance: the European Diabetes Prevention RCT in Newcastle upon Tyne, UK. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:342. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pina IC, Gautschi JT, Wang GY, Sanders ML, Schmitz FJ, France D, et al. Psammaplins from the sponge Pseudoceratina purpurea: inhibition of both histone deacetylase and DNA methyltransferase. J Org Chem. 2003;68:3866–3873. doi: 10.1021/jo034248t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plummer SM, Holloway KA, Manson MM, Munks RJ, Kaptein A, Farrow S, et al. Inhibition of cyclo-oxygenase 2 expression in colon cells by the chemopreventive agent curcumin involves inhibition of NF-kappaB activation via the NIK/IKK signalling complex. Oncogene. 1999;18:6013–6020. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pop EA, Fischer LM, Coan AD, Gitzinger M, Nakamura J, Zeisel SH. Effects of a high daily dose of soy isoflavones on DNA damage, apoptosis, and estrogenic outcomes in healthy postmenopausal women: a phase I clinical trial. Menopause. 2008;15:684–692. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318167b8f2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]