Abstract

The developmental origins of adult health and disease (DOHaD) hypothesis that argues for a causal relationship between under-nutrition during early life and increased risk for a range of diseases in adulthood is gaining epidemiological support. One potential mechanism mediating these effects is the modulation of epigenetic markings, specifically DNA methylation. Since folate is an important methyl donor, alterations in supply of this micronutrient may influence the availability of methyl groups for DNA methylation. We hypothesised that low folate supply in utero and post-weaning would alter the DNA methylation profile of offspring. In two separate 2 × 2 factorial designed experiments, female C57Bl6/J mice were fed low- or control/high-folate diets during mating, and through pregnancy and lactation. Offspring were weaned on to either low- or control/high-folate diets, resulting in 4 treatment groups/experiment. Genomic DNA methylation was measured in the small intestine (SI) of 100-day-old offspring. In both experiments, SI genomic DNA from offspring of low-folate-fed dams was significantly hypomethylated compared with the corresponding control/high folate group (P = 0.009/P = 0.006, respectively). Post-weaning folate supply did not affect SI genomic DNA methylation significantly. These observations demonstrate that early life folate depletion affects epigenetic markings, that this effect is not modulated by post-weaning folate supply and that altered epigenetic marks persist into adulthood.

Keywords: Folate, DNA methylation, Pregnancy, Development, Mouse

Introduction

Epidemiological evidence suggests exposures during early life may contribute to adulthood disease risk. Specifically, the association between lower birth weight and increased risk of type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease and hypertension has been attributed to poor nutrition in utero [2]. Such observations underpin the concept of developmental plasticity [4], underscore the potential for phenotypic diversity from a fixed genotype and provide the basis for the developmental origins of health and disease (DOHaD) hypothesis. If early life exposures are important in determining later health outcomes, then such exposures must “mark” the animal at a molecular, cellular and/or tissue level.

Epigenetic marks, including CpG methylation and covalent histone modifications, are established during development and constitute a rich information source layered on top of the DNA sequence. These marks determine stable transcription, allowing cell-specific gene expression that is essential for cell differentiation [5]. Maternal nutrition alters DNA methylation patterns that are associated with altered gene expression and phenotypic changes in rodent offspring [9, 19, 34].

Many studies highlight the detrimental effects of low folate status before and during pregnancy on the health of the offspring. Low folate status, particularly during early pregnancy, increases the risk of neural tube defects (NTDs) in the foetus [12], and evidence suggests that low folate status during pregnancy is linked with low birth weight [29]. Since folate is a key source of S-adenosyl methionine (SAM)—the universal methyl donor—it is an attractive nutrient for modulating epigenetic components of early programming. Studies in the Avy mouse established the importance of methyl group supply in determining adult phenotype and produced evidence for a mechanistic role for altered DNA methylation in mediating gene expression changes and associated phenotypic changes [9, 34]. In rats, low maternal protein intake resulted in reduced promoter methylation and enhanced expression of glucocorticoid receptor (GR) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPARα) in offspring liver [19]. Dietary supplementation with folic acid (5 mg/kg diet) prevented these changes [19]. In sheep, restricting vitamin B12, folate and methionine periconceptually resulted in differential methylation of 4% of 1400 CpG islands (CGI) in foetal liver [30]. In rats, a low-folate diet during pregnancy led to reduced placental DNA methylation [15]. Recently, Steegers-Theunissen et al. [32] reported that maternal use of folic acid supplements during pregnancy was associated with increased methylation within the DMR of the IGF2 gene of 17-month-old children. Furthermore, maternal, but not child, S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) blood concentrations were associated with the children’s IGF2 DMR methylation levels, indicating that the maternal dietary environment rather than the offspring’s subsequent environmental exposures had the greater influence on methylation of this gene domain [32].

The DOHaD theory proposes that the development of several complex diseases in adulthood is influenced by early life events such as dietary exposure in utero. Although there is limited evidence of associations between early life exposures and cancer incidence [14], a recent study observed that early life exposure to famine was associated with decreased risk of developing a CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) colorectal tumour [13]. The presence of a CIMP tumour is indicative of epigenetic instability coupled with transcriptional silencing of gene expression and microsatellite instability [11, 31]. The observations of Hughes et al. [13] provide proof of principle that early life exposures may result in persistent epigenetic alterations that may influence the development of colorectal cancer (CRC) in later life. Since there is strong evidence that epigenetic events play an important role in the development of CRC [16], we have investigated the effects of folate depletion during early development on intestinal tumorigenesis. The ApcMin/+ mouse is a murine model of familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) (a form of CRC caused by a germline mutation in the APC gene), which develops multiple tumours in the small intestine [22]. We have used this mouse model to investigate the effects of altering folate supply in utero and after weaning on intestinal tumour development, and reported that folate depletion post-weaning was protective against neoplasia in female mice [21].

In present study, we have attempted to test the hypothesis that folate supply during early development alters DNA methylation. We have manipulated folate supply via the mother (during development in utero and during lactation) and/or directly to the offspring via the post-weaning diet. The proximal SI was chosen as our target tissue because of our interest in the effects of folate on intestinal tumorigenesis and the fact that most tumours occur in the proximal SI in the Apc-driven murine model of CRC [21]. We carried out two separate mouse studies that shared several key aspects of their protocols but differed in the duration of folate depletion of dams before mating and in the protein and folate content of the “control” (folate adequate) diet.

Materials and methods

Dietary strategy

Two separate mouse experiments (Expt. 1 and Expt. 2) were conducted. Experimental diets were modified from AIN-93G [27]. Protein was provided by an l-amino acid mixture that was included at 175 and 100 g/kg in Expts. 1 and 2, respectively. The lower protein content of the diet in Experiment 2 was designed to reduce the overall methyl donor pool by lowering methionine supply. Methionine concentrations in the diets were 8.2 and 0.3 g/kg in Expts. 1 and 2, respectively, whilst choline bitartrate concentrations were 2.5 and 1.5 g/kg in Expt. 1 and 2, respectively. Fat (soybean oil and lard) and sucrose concentrations were each increased to 150 g/kg diet in all diets to mimic important characteristics of Western human diets.

In Expt. 1, dams were fed a low-folate breeding (0.4 mg folic acid/kg diet) (LB) or a control (2 mg folic acid/kg diet) (C) diet during pregnancy and lactation. At weaning, offspring were randomised to low-folate-weaning (0.26 mg folic acid/kg diet) (LW) or control (C) diets, resulting in four groups LB-LW, LB-C, C-LW and C-C.

In Expt. 2, designed to investigate the effects of a wider range of folate supply, dams were fed low-folate breeding (0.4 mg folic acid/kg diet) (LB) or high-(8 mg folic acid/kg diet) (H) folate diets during pregnancy and lactation. At weaning, offspring were randomised to a very low (0.00 mg folic acid/kg diet) (VL) or high (H)-folate diet resulting in four groups LB-VL, LB-H, H-VL and H-H.

Animal housing, husbandry and diet intervention

Animals were housed in the Comparative Biology Centre (Newcastle University) at 20–22°C with 12-h light/dark cycles. Fresh water was available ad libitum. All animal procedures were approved by the Newcastle University Ethics Review Committee and the Home Office.

Experiment 1

Mating trios (two C57BL/6 J females (8 weeks old), one male) were offered 6 g/day/mouse of C or LB diet. Pregnant females were re-caged and offered 10 g/day/mouse of their allocated diet throughout pregnancy. At 2 weeks post-partum, diet quantity was increased (20 g/day/mouse). Following weaning (mean 32 days post-partum), offspring were re-caged (1–4 per cage) and randomly assigned to C or LW diet (6 g/day/mouse). At 96 days (SD ± 5) old, mice were killed.

Kinetics of folate depletion

Before undertaking Expt. 2, a study was carried out to determine the time required on a very low-folate diet (0 mg/kg folic acid) (VL) to reduce folate status to a new equilibrium. Pairs of 24-week-old female C57BL/6 J mice were offered 6 g/day/mouse of VL diet. At baseline, and weekly for the next 7 weeks, mouse pairs were anaesthetised and blood collected via cardiac puncture. Red blood cell (RBC) folate concentrations were measured by automated ion capture assay (Abbot IMx; Abbot Laboratories) as described previously [3].

Experiment 2

Female C57BL/6 J mice (8 weeks old) were allocated at random to H or LB diets (6 g/day/mouse) and maintained on this diet for 5 weeks prior to mating. Mating trios (two females, one male) were offered 10 g/day/mouse of allocated diet. Pregnant females were re-caged and offered 20 g diet/day/mouse throughout pregnancy. At 2 weeks post-partum, diet quantity was increased (30 g/day/mouse). This increase compared with Expt. 1 was intended to maximise offspring survival due to the reduced protein concentration in the diets in Expt. 2. Following weaning (32 mean days post-partum), animals were re-caged (1–4 per cage) and randomly assigned to H or VL diet (6 g/day). At mean 99 days (SD ± 55), animals were killed.

Sample collection

The small intestine (SI) was removed and cut into 2 equal length sections (proximal and terminal SI). SI sections were opened longitudinally and tissue washed with PBS. In Expt. 2, proximal SI was cut into 2 equal sections and mucosa collected from the distal section. SI tissues and mucosa were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Blood was collected by cardiac puncture and stored at −80°C.

DNA extraction and genomic DNA measurement

DNA was extracted (including RNase treatment) using a Qiagen DNA mini kit (Qiagen-51306) following the manufacturer’s protocol from the proximal SI whole tissue (Expt. 1) and from mucosal scrapes taken from the proximal SI (Expt. 2). Concentration and quality of DNA were checked using an Eppendorf BioPhotometer. Genomic DNA methylation was measured using the cytosine extension assay as described previously [24]. Briefly, 2 μg DNA were incubated with and without 1 Unit restriction enzyme HpaII (NE Biolabs), final volume 40 μl, 37°C for 16 h. Three 10-μl aliquots were removed and placed on ice. Fifteen microlitres of cytosine extension mix (0.5 U Taq Polymerase (Promega), 1× buffer, 1 mM MgCl2 and 0.25 μCi 5,5′ 3H-Deoxycytidine ([3H]dCTP) triphosphate tetrasodium salt (Perkin Elmer)] was added, with a drop of mineral oil and incubated at 55°C for 1 h. Samples were placed on ice for 5 min, then 20 μl of sample mixture pipetted onto a DE81 Whatman filter paper and left to dry for 10 min. Filter papers were washed 3 times in 50 ml of 0.5 M sodium phosphate buffer pH 7 (10 min/wash), followed by an ethanol (70%) wash (10 min) and left to dry for 30 min. Each filter was immersed in 10 ml scintillation fluid and counted in a scintillation counter.

Statistical analysis

Data distributions were examined by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. All data were normally distributed. Data were analysed using analysis of variance to examine the effects of sex, maternal and post-weaning diets.

Results

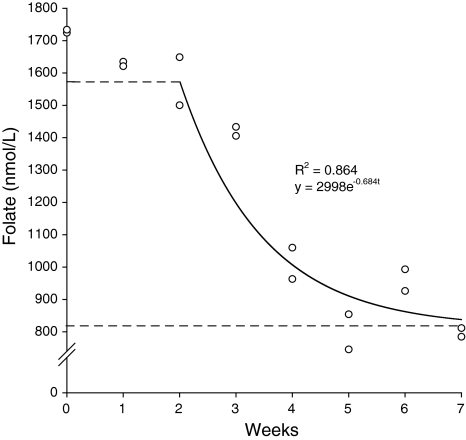

Effects of low-folate diet on kinetics of change in RBC folate concentration

When introduced to the VL diet, RBC folate concentrations fell little over 2 weeks from an initial mean concentration of 1,729 nmol/ml (Fig. 1). Thereafter, there was an exponential decline, reaching a new equilibrium of approximately 850 nmol/ml folate at 4–5 weeks. The rate constant for this decline was 0.684, indicating a RBC folate half life of 7.09 days. There was little change in RBC folate concentration over the following 2–3 weeks. These data showed the VL diet reduced folate status by about 50% in 5 weeks so, in Expt. 2, dams were fed the low-folate diet (LB) for 5 weeks prior to mating to ensure periconceptual depletion.

Fig. 1.

Exponential decay of red blood cell folate concentration in female mice following transfer to low-folate diet

Effects of folate supply on pregnancy outcome and maternal RBC folate concentration

In both studies, no malformations were observed in the offspring from dams fed the low-folate diets during pregnancy and lactation. In Expt. 1, the maternal low-folate (LB) diet during pregnancy reduced the number of pups born by 22% (P = 0.006 [21]. There was a smaller reduction (17%) in the numbers of pups born in Expt. 2 (4.39 vs. 3.68 for high (H)- and low (LB)-folate diets, respectively) and this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.398).

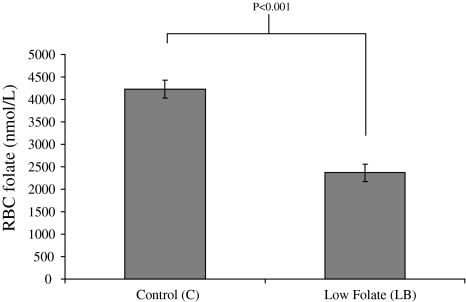

In Expt. 1, dams fed the low-folate (LB) diet had significantly (P < 0.001) lower RBC folate concentrations when compared with control diet (N)—fed dams (Fig. 2). For technical reasons, RBC folate data are not available for Expt. 2.

Fig. 2.

Effects of folate supply during pregnancy and lactation on maternal RBC folate concentrations. (Errorbars represent SEM)

Effect of folate supply during pregnancy and lactation and post-weaning on adult offspring weight

In Expt. 1, neither maternal folate depletion during pregnancy and lactation nor post-weaning folate depletion affected body weight of adult offspring. In addition, there was no interaction between the pre- and post-weaning diets on adult offspring body weight (Table 1). However, in Expt. 2, low folate feeding during either pregnancy and lactation or post-weaning caused significant reductions in adult body weight (Table 2).

Table 1.

Effects of altered folate supply during pregnancy and lactation (pre-weaning) and post-weaning on body weight and RBC folate concentrations in adulthood (Experiment 1)

Bold value is statistically significant

Table 2.

Effects of altered folate supply during pregnancy and lactation (pre-weaning) and post-weaning on body weight in adulthood (Experiment 2)

Bold values are statistically significant

Effect of folate supply during pregnancy and lactation and post-weaning on RBC folate concentrations of adult offspring

In Expt. 1, maternal folate depletion during pregnancy and lactation did not alter RBC folate concentrations in adult offspring significantly (Table 1). However, as expected, feeding the folate-depleted diet (LW) post-weaning reduced RBC folate concentrations significantly (Table 1). There was no evidence of an interaction between pre- and post-weaning diets on offspring RBC folate concentrations. For technical reasons, equivalent data for Expt. 2 are not available.

Effect of folate supply during pregnancy and lactation on proximal SI genomic DNA methylation

In Expt. 1, low folate (LB) during pregnancy and lactation caused a significant (P = 0.009) fall in genomic DNA methylation in proximal SI tissue of offspring compared with control offspring (Fig. 3a). Similarly, in Expt. 2, when compared with offspring of high-folate-fed dams, proximal SI epithelial genomic DNA methylation was significantly lower (i.e. hypomethylated) in offspring exposed to low folate (LB) during pregnancy and lactation (P = 0.006) (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

Effects of folate supply during pregnancy and lactation and post-weaning on genomic DNA methylation in a proximal SI tissue (Expt. 1) and b proximal SI mucosa (Expt. 2) of adult offspring. Higher values indicate reduced DNA methylation. (Errorbars represent confidence intervals)

Effect of post-weaning folate supply on proximal SI genomic DNA methylation

Proximal SI genomic DNA methylation tended to be lower in offspring given low-folate diets from weaning in both experiments; however, these changes were not statistically significant (Expt. 1, P = 0.191; Expt. 2, P = 0.431) (Fig. 3). In addition, there were no significant interactions between maternal and post-weaning folate supply.

Discussion

In previous rodent studies where maternal folate status has been manipulated, there was considerable inter-study variation in the preconception run-in period. Some studies did not include any run-in period [19, 21], whereas others fed experimental diets for 2–8 weeks prior to mating [8, 28, 33–36]. No rationale for the duration of these periods was offered. Novel data from this project demonstrate that feeding the very low-folate diet for 4–5 weeks was sufficient to provoke a ~50% reduction in RBC folate concentration. This decline in RBC folate concentration occurred in three phases, an initial 2-week lag period was followed by an exponential decline until 4–5 weeks, after which there was no further change. The lag period suggests folate stores, e.g. plasma and liver, were sufficient to buffer RBC folate concentrations against folate depletion for about 2 weeks. In addition, there may have been some re-cycling of folate derived from RBC degradation for use by newly formed RBCs [18]. However, when these stores were exhausted, RBC folate concentration dropped rapidly, until 4–5 weeks, at which point it stabilized. This suggests that a 4–5 week run-in period on the VL diet is sufficient to reduce RBC folate by ~50%.

In the present studies, we observed that folate depletion during pregnancy and lactation caused DNA hypomethylation in the small intestine of adult offspring, regardless of post-weaning folate intake. It is important to note that the levels of maternal folate depletion in these experiments were moderate, and although folate depletion reduced maternal RBC folate concentrations and litter size, there were no signs of folate deficiency in these animals in terms of physical malformations. Our observation of significantly reduced genomic DNA methylation in the offspring proximal SI of folate depleted dams highlights the plasticity of the epigenome during development and its susceptibility to relatively subtle environmental influences.

The role of folate as a methyl donor provides a mechanistic basis to support the hypothesis that folate supply may alter DNA methylation. Previous studies reported that changes in maternal methyl donor supply, including folate, alter offspring DNA methylation. For example, Waterland et al. [34] reported that offspring of dams fed methyl supplements during pregnancy were more likely to have brown coats, due to reduced expression of the agouti gene via increased DNA methylation at the agouti locus. Lillycrop et al. [19] observed that supplementing a protein-restricted diet with folic acid normalised methylation of GR and PPAR promoters, which were hypomethylated after feeding the protein-restricted diet. Furthermore, Sinclair et al. [30] reported altered methylation status in foetal liver of sheep in response to maternal periconceptional restriction of vitamin B12 and folate, and Kim et al. [15] observed that maternal folate deficiency in rats resulted in decreased placental DNA methylation. Recently, the effects of maternal folic acid supplementation during pregnancy on DNA methylation in 17-month-old children have been reported [32]. Increased methylation in the IGF2 DMR was observed in the children born to mothers who used folic acid supplements compared with children of mothers who did not use such supplements. Maternal, but not children’s, circulating SAM concentrations were associated with children’s IGF2 DMR methylation levels. This observation indicates the importance of maternal nutritional environment in influencing epigenetic marks in their offspring [32].

The impact of DNA methylation changes reported here on function in the offspring remains to be elucidated. In Expt. 1, there was no detectable effect of maternal or post-weaning folate supply on adult body weight, whereas in Expt. 2, folate depletion at either life stage led to reduced body weight in adulthood. The difference between studies may be due to the much lower protein (and methionine) content of the diet used in Expt. 2 (100 vs. 175 g amino acids/kg diet in Expts. 1 and 2, respectively) which may have made the animals more vulnerable to the effects of folate depletion. Unfortunately, for technical reasons, we were unable to obtain estimates of RBC folate concentration in Expt. 2 so that we cannot make a direct comparison between the folate status of mice in the 2 experiments. However, aberrations in genomic DNA methylation, specifically genomic hypomethylation, are observed in numerous diseases, including cancer, and in ageing [6, 23], so it is possible that the epigenetic modifications observed here may have long-term health implications. Global DNA hypomethylation is observed in the early stages of CRC [10] and may contribute to susceptibility to development of the disease. Given that there is some level of conservation in terms of DNA methylation between the human colon and mouse small intestine [20], it is plausible that the epigenetic events reported here may also occur in the human colon. Our observation that altering the maternal folate supply during pregnancy and lactation can result in changes in DNA methylation in the offspring highlights the importance of understanding which maternal dietary factors, in which time windows, modulate the epigenetic signature of their children. Such understanding may help to define appropriate standards for maternal nutrition during pregnancy to optimise adult health in the next generation. Further investigation, including the analysis of DNA methylation in candidate genes known to be sensitive to methylation changes in cancer and changes in DNA methylation in other tissues, is needed to explore the potential health implications of these early life exposures.

Post-weaning folate depletion did not alter DNA methylation in either experiment. Reported effects of low methyl donor diets fed after weaning on DNA methylation differ between studies. Methyl donor deficiency resulted in DNA hypomethylation in liver [1, 7, 26], but hypermethylation in brain of adult rats [25]. More recently, Kotsopoulos et al. [17] observed that a folate deficient diet given from infancy to puberty, but not into adulthood, induced hepatic DNA hypermethylation in adult rats. It is probable that several factors influence the responses to such dietary manipulations including the form and dose of methyl donor, target tissue, and perhaps most critically, the time point and duration of the intervention. It is possible that the juvenile epigenome is more vulnerable to environmental influences such as reduced folate supply [17]. In the present studies, the folate depletion used in the post-weaning phase may not have been sufficient to cause DNA methylation changes in the tissue of interest, although this was sufficient to reduce other biochemical indices of folate status as shown in Table 1. Our observation of reduced genomic DNA methylation in adult tissue following folate depletion in utero and during lactation suggests that the critical window of exposure for such modest folate depletion was pre-weaning.

In conclusion, modest depletion in maternal folate supply reduced genomic DNA in adult offspring, suggesting that folate availability during gestation and lactation is an important factor in determining long-term DNA methylation status in offspring. However, it is not yet clear what phenotypic or health consequences, if any, these programmed epigenetic events have for the adult. Further studies investigating the both phenotypic traits and epigenetic profiles due to such maternal influences are warranted.

Acknowledgments

We thank Adele Kitching, CBC, Newcastle University for care of the animals. This project was funded by a BBSRC studentship held by JAM (01/A1/D/17951), a World Cancer Research Fund (2001/37) grant to EAW and JCM, and support from The European Nutrigenomics Organisation (NuGO) to JCM, provided via the Nutritional Epigenomics Focus Team. Study design by JCM and EAW, laboratory work by JAM and KJW. All authors contributed to data analysis. JAM and JCM wrote the manuscript with contributions from EAW and KJW. There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Balaghi M, Wagner C. DNA methylation in folate deficiency: use of cpg methylase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;193(3):1184–1190. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barker DJ. The developmental origins of well-being. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004;359(1449):1359–1366. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basten GP, Hill MH, Duthie SJ, Powers HJ. Effect of folic acid supplementation on the folate status of buccal mucosa and lymphocytes. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13(7):1244–1249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bateson P, Barker D, Clutton-Brock T, Deb D, D’Udine B, Foley RA, Gluckman P, Godfrey K, Kirkwood T, Lahr MM, McNamara J, Metcalfe NB, Monaghan P, Spencer HG, Sultan SE. Developmental plasticity and human health. Nature. 2004;430(6998):419–421. doi: 10.1038/nature02725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bird A. DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory. Genes Dev. 2002;16(1):6–21. doi: 10.1101/gad.947102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calvanese V, Lara E, Kahn A, Fraga MF. The role of epigenetics in aging and age-related diseases. Ageing Res Rev. 2009;8(4):268–276. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christman JK, Sheikhnejad G, Dizik M, Abileah S, Wainfan E. Reversibility of changes in nucleic acid methylation and gene expression induced in rat liver by severe dietary methyl deficiency. Carcinogenesis. 1993;14(4):551–557. doi: 10.1093/carcin/14.4.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooney CA, Dave AA, Wolff GL. Maternal methyl supplements in mice affect epigenetic variation and DNA methylation of offspring. J Nutr. 2002;132(8 Suppl):2393S–2400S. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.8.2393S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dolinoy DC, Weidman JR, Waterland RA, Jirtle RL. Maternal genistein alters coat color and protects avy mouse offspring from obesity by modifying the fetal epigenome. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114(4):567–572. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fearon ER, Vogelstein B. A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell. 1990;61(5):759–767. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90186-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferguson LR, Karunasinghe N, Philpott M. Epigenetic events and protection from colon cancer in New Zealand. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2004;44(1):36–43. doi: 10.1002/em.20029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frey L, Hauser WA. Epidemiology of neural tube defects. Epilepsia. 2003;44(Suppl 3):4–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.44.s3.2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hughes LA, Brandt PA, Bruine AP, Wouters KA, Hulsmans S, Spiertz A, Goldbohm RA, Goeij AF, Herman JG, Weijenberg MP, Engeland M. Early life exposure to famine and colorectal cancer risk: a role for epigenetic mechanisms. PLoS One. 2009;4(11):e7951. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson KJ, Springer NM, Bielinsky AK, Largaespada DA, Ross JA. Developmental origins of cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69(16):6375–6377. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim JM, Hong K, Lee JH, Lee S, Chang N. Effect of folate deficiency on placental DNA methylation in hyperhomocysteinemic rats. J Nutr Biochem. 2009;20(3):172–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim MS, Lee J, Sidransky D (2010) DNA methylation markers in colorectal cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev 29 (1):181–206 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Kotsopoulos J, Sohn KJ, Kim YI. Postweaning dietary folate deficiency provided through childhood to puberty permanently increases genomic DNA methylation in adult rat liver. J Nutr. 2008;138(4):703–709. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.4.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lamers Y, Prinz-Langenohl R, Bramswig S, Pietrzik K. Red blood cell folate concentrations increase more after supplementation with [6 s]-5-methyltetrahydrofolate than with folic acid in women of childbearing age. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84(1):156–161. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lillycrop KA, Phillips ES, Jackson AA, Hanson MA, Burdge GC. Dietary protein restriction of pregnant rats induces and folic acid supplementation prevents epigenetic modification of hepatic gene expression in the offspring. J Nutr. 2005;135(6):1382–1386. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.6.1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maegawa S, Hinkal G, Kim HS, Shen L, Zhang L, Zhang J, Zhang N, Liang S, Donehower LA, Issa JP. Widespread and tissue specific age-related DNA methylation changes in mice. Genome Res. 2010;20(3):332–340. doi: 10.1101/gr.096826.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKay JA, Williams EA, Mathers JC. Gender-specific modulation of tumorigenesis by folic acid supply in the apc mouse during early neonatal life. Br J Nutr. 2008;99(3):550–558. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507819131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moser AR, Pitot HC, Dove WF. A dominant mutation that predisposes to multiple intestinal neoplasia in the mouse. Science. 1990;247(4940):322–324. doi: 10.1126/science.2296722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ozanne SE, Constancia M. Mechanisms of disease: the developmental origins of disease and the role of the epigenotype. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2007;3(7):539–546. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pogribny I, Yi P, James SJ. A sensitive new method for rapid detection of abnormal methylation patterns in global DNA and within cpg islands. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;262(3):624–628. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pogribny IP, Karpf AR, James SR, Melnyk S, Han T, Tryndyak VP. Epigenetic alterations in the brains of fisher 344 rats induced by long-term administration of folate/methyl-deficient diet. Brain Res. 2008;1237:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.07.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pogribny IP, Ross SA, Wise C, Pogribna M, Jones EA, Tryndyak VP, James SJ, Dragan YP, Poirier LA. Irreversible global DNA hypomethylation as a key step in hepatocarcinogenesis induced by dietary methyl deficiency. Mutat Res. 2006;593(1–2):80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reeves PG, Nielsen FH, Fahey GC., Jr Ain-93 purified diets for laboratory rodents: final report of the American institute of nutrition ad hoc writing committee on the reformulation of the ain-76a rodent diet. J Nutr. 1993;123(11):1939–1951. doi: 10.1093/jn/123.11.1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sakanashi TM, Rogers JM, Fu SS, Connelly LE, Keen CL. Influence of maternal folate status on the developmental toxicity of methanol in the cd-1 mouse. Teratology. 1996;54(4):198–206. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9926(199610)54:4<198::AID-TERA4>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scholl TO, Johnson WG. Folic acid: influence on the outcome of pregnancy. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71(5 Suppl):1295S–1303S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.5.1295s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sinclair KD, Allegrucci C, Singh R, Gardner DS, Sebastian S, Bispham J, Thurston A, Huntley JF, Rees WD, Maloney CA, Lea RG, Craigon J, McEvoy TG, Young LE. DNA methylation, insulin resistance, and blood pressure in offspring determined by maternal periconceptional b vitamin and methionine status. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(49):19351–19356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707258104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Slattery ML, Wolff RK, Curtin K, Fitzpatrick F, Herrick J, Potter JD, Caan BJ, Samowitz WS. Colon tumor mutations and epigenetic changes associated with genetic polymorphism: Insight into disease pathways. Mutat Res. 2009;660(1–2):12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steegers-Theunissen RP, Obermann-Borst SA, Kremer D, Lindemans J, Siebel C, Steegers EA, Slagboom PE, Heijmans BT. Periconceptional maternal folic acid use of 400 μg per day is related to increased methylation of the igf2 gene in the very young child. PLoS One. 2009;4(11):e7845. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trentin GA, Moody J, Heddle JA. Effect of maternal folate levels on somatic mutation frequency in the developing colon. Mutat Res. 1998;405(1):81–87. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(98)00147-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Waterland RA, Jirtle RL. Transposable elements: targets for early nutritional effects on epigenetic gene regulation. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(15):5293–5300. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.15.5293-5300.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wolff GL, Kodell RL, Moore SR, Cooney CA. Maternal epigenetics and methyl supplements affect agouti gene expression in avy/a mice. Faseb J. 1998;12(11):949–957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiao S, Hansen DK, Horsley ET, Tang YS, Khan RA, Stabler SP, Jayaram HN, Antony AC. Maternal folate deficiency results in selective upregulation of folate receptors and heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein-e1 associated with multiple subtle aberrations in fetal tissues. Birth Defects Res Clin Mol Teratol. 2005;73(1):6–28. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]