Abstract

Good predictions of the local mechanical environment of the tissue with known geometry and applied loads are fundamental to quantifying the biological response of tissues to mechanical stimuli. Whereas mean stresses in cylindrical sections of blood vessels may be calculated directly from measured loads and vessel geometry (e.g., Laplace’s law), predicting how these stresses are distributed across the wall requires knowledge of the constitutive behavior of the tissue. Previously, we reported biaxial biomechanical data for mouse carotid arteries before and after exposure to altered axial extension in organ culture. Here we considered phenomenological and microstructurally motivated constitutive models and identified material parameters for each via nonlinear regression. Specifically, we considered the model of Chuong and Fung, a four fiber-family model, and several new variants of a rule-of-mixtures model; in the latter, we modeled the artery as a mixture of collagen, elastin, muscle, and water. We found that the four fiber-family model fitted data significantly better than the model of Chuong and Fung. When identifying parameters for the rule-of-mixtures models, we imposed penalties that required each constituent to be structurally significant; e.g., elastin contributing significantly to the overall response over low loads and collagen dominating the response over high loads. Such constraints ascribe additional microstructural “meaning” to the constitutive model. Although imposing such penalties necessarily reduces the goodness of fit of model predictions to experimental data compared to regression without such penalties, the modest reduction in the goodness of fit observed in our results was off-set by the improved structural interpretation such models provide. Such microstructurally motivated models will be useful in characterizing vascular growth and remodeling in terms of the evolution of microstructural metrics that may be quantified experimentally.

Keywords: vascular mechanics, mechanical behavior, stress, remodeling

1 Introduction

Mechanically mediated vascular remodeling occurs as vascular cells sense and respond to their local mechanical environment. Thus, fundamental to many studies of vascular remodeling is the quantification of the local mechanical environment under specific loading conditions; i.e., determining the distribution of stresses and strains of a vessel under applied loads (e.g., pressure, axial extension, luminal flow, etc.). Knowledge of the constitutive behavior of the vessel wall allows one to predict the local stresses and strains throughout the wall for a vessel of known geometry and applied loads. Given that the material response of biological tissues is governed by their internal constitution (i.e., cell and extracellular matrix content and organization), many argue that a predictive, widely applicable constitutive relation for arteries and other soft tissues must include parameters that account for the underlying microstructure [1–4]. Such models will be particularly useful in quantifying remodeling responses associated with development, aging, disease progression, and clinical interventions, where the evolution of structural parameters may be experimentally quantified.

Previously, we reported the evolution of the biaxial biomechanical behavior and geometry of mouse carotid arteries exposed to normal pressure and luminal flow but altered axial extension [5]. In this paper, we identified material parameters for constitutive models available in literature and for newly proposed constitutive models by fitting biaxial mechanical data from mouse carotid arteries prior to and after exposure to altered axial extension in organ culture. We found that a four fiber-family model [6] fits the data significantly better than the model of Chuong and Fung [7]. We also considered several variants of a rule-of-mixtures constitutive model [8]. We considered four structurally significant constituents (collagen, elastin, smooth muscle, and water). In addition to minimizing the error between experimental data and model predictions, we imposed penalties that required each constituent to be structurally significant. That is, we enforced penalties that encouraged parameter sets in which elastin contributes significantly to the overall response over low loads and collagen dominates the response over high loads. These constraints ascribe additional microstructural meaning to the constitutive model. Whereas imposing such penalties necessarily reduces the goodness of fit of model predictions to experimental data, we submit that the marginal reduction in the goodness of fit observed in our results was off-set by the improved structural interpretation.

2 Theoretical Framework

2.1 Phenomenological Models

Kinematics

In traditional vascular mechanics, one typically considers three configurations: a loaded configuration βt, a traction-free (unloaded) configuration βu, and a (nearly stress-free) reference configuration βo; see Ref. [7]. For inflation and extension of an axisymmetric tube, the deformation gradient, right Cauchy–Green strain, and Green strain tensors have components

| (1) |

where

| (2) |

and Λ and λ are the axial stretches for the motions from βo to βu and from βu to βt, respectively, and Θo is the sectorial angle in βo. If the material is assumed to be incompressible, det(F)=1, and the current radius may be related to the reference radius as

| (3) |

where Ri and Ro are the inner or outer radii in βo, and ri and ro are the inner and outer radii in βt. Thus, given measured values for the reference configuration (Ri, Ro, the stress-free axial length Lz, and Θo) and the current configuration (ro or ri) and the loaded length (ℓ), the components of F, C, and E are easily calculated.

Unfortunately, in Ref. [5], opening angle measurements were not performed for the freshly isolated and cultured vessels. Thus, here we approach the problem in an inverse fashion. Let us prescribe the state of strain in the in vivo (loaded) configuration. Let the inner radius, outer radius, and length in the in vivo configuration be denoted , and ℓh, and let the homeostatic stretches be denoted , and , where . Now, we may define the true stress-free (or natural) configuration of a material point located in a current configuration at radius r ∈ [ri, ro] by defining a reference radius and length as

| (4) |

where Rn is the radius and is the axial length of a cylindrical shell for which the stress is zero (for this material point); is the arc length of this cylindrical shell. Given Eq. (4) in any (tubular) configuration with inner radius ri and length ℓ, the current radius may be calculated via incompressibility as

| (5) |

and the stretches may be calculated as

| (6) |

Given these stretches the components of F, C, and E for extension and inflation are easily calculated via Eq. (1).

Equilibrium

For inflation and extension of a long, straight, axi-symmetric tube, equilibrium requires that Trθ=Trz =0 and ∂Trr/∂r+(Trr − Tθθ)/r=0. Noting that −Trr(ri) = P is the luminal pressure and Trr(ro) =0, equilibrium requires that

| (7) |

where

| (8) |

T̂ is the so-called “extra” stress due to the deformation and W is the strain energy density function. Axial equilibrium requires that the magnitude of the axial force, f, maintaining the in vivo axial extension be

| (9) |

where the first term on the right hand side is due to the traction force applied to the vessel wall and the second term on the right hand side is due to the pressure acting over the end cap; Γ=1 or 0 for a closed or open ended tube, respectively. Equation (9) can be written as

| (10) |

see Ref. (9). For ex vivo biomechanical testing, Γ=1. Given Eq. (1) and Eq. (2) or (6) the components of the extra stress may be calculated as

| (11) |

where i=r, θ, or z.

Constitutive equations

We considered the model of Chuong and Fung [7], a four fiber-family model, and several variants of a rule-of-mixtures model to describe the constitutive behavior of these vessels.

Fung model

Consider the strain energy function of Chuong and Fung [7]

| (12) |

where

| (13) |

and where c and c1–6 are material parameters. Given this strain energy function, the components of the extra stress due to the deformation are

| (14) |

Four fiber-family model

Consider a four fiber-family proposed by Baek et al. [6], which is a simple extension of the model proposed by Holzapfel et al. [3] and Spencer [10], with strain energy function

| (15) |

where b, , and are material parameters with k denoting the kth fiber-family, I1 =tr(C)=Crr + Cθθ+Czz is the first invariant of C, is the stretch of the kth fiber-family, Mk =sin(αk)eθ + cos(αk)ez is the unit vector along the kth fiber direction in the reference configuration, and αk is the associated angle between the axial and fiber directions. In general, (λk)2 = Cθθ sin2(αk) +2Cθz sin(αk)cos(αk) + Czz cos2(αk), but Cθz =0 for inflation and extension tests, given material symmetry. In addition, we note that under compression the fiber-families do not contribute to the mechanical response in an exponential fashion, as they do in tension. Thus, when λk < 1, we set ; therefore, we model the vessel under compression as a neo-Hookean material. Here, we consider four fiber-families with α1=90 deg (circumferential), α2=0 deg (axial), and α3=−α4=α (diagonal), which is left as a variable to be determined along with the seven material parameters (with and for the diagonal fibers to ensure material symmetry) via nonlinear regression. Given this strain energy function, the components of the extra stress due to the deformation are

| (16) |

from which P and f can be calculated via Eqs. (7) and (10). Note that λ(3) = λ(4) is the stretch in fiber k=3 (and k=4).

2.2 Microstructurally Motivated Models: A Discrete Set of Fibers

It has long been thought that elastin contributes to the highly distensible region on pressure-diameter curves of arteries at low pressures and collagen contributes to the stiff region of these curves at high pressures; see, for example, the classic paper by Roach and Burton [11]. Smooth muscle cells also contribute significantly to the overall mechanical response of blood vessels, under both passive and active (contractile) conditions. Indeed, other key structural constituents have also been implicated as significant contributors to the overall mechanical response [12]. The amount, organization, and mechanical state of key structural constituents can vary spatially in arteries and can vary temporally as different constituents are produced, degraded, and remodeled. As the tissue remodels and grows, constituent turnover and growth can occur at different rates and to different extents. Constrained mixture theory provides a convenient theoretical framework for quantifying the spatial and temporal variations in mechanical behavior in terms of microstructural metrics.

Constitutive equations: Nonuniform constrained mixture

We will adopt a simple rule-of-mixtures approach; that is, let the total stress be given as the sum of the stresses borne by key, individual structural constituents. In particular, we will follow Gleason et al. [8] and let

| (17) |

where φj(r) is the mass fraction of constituent j, which may vary with position, T is the total (mixture) stress at a point, Tj is the (passive) stress borne by constituent j, and is the active (contractile) stress borne by constituent j. The passive response of each constituent will be modeled as an incompressible elastic material; thus

| (18) |

where we also allow the material to be nonuniform. That is, at each point, each passive constituent may be present at a different state of strain (i.e., possess different stress-free configurations); thus, each constituent can experience different deformations.

Let us consider the passive response of the blood vessel; i.e., let . Given Eq. (18), Eq. (17) may be rewritten as

| (19) |

where T̂ j=2Fj(∂Wj/∂Cj)(Fj)T is the extra stress due to the deformation for constituent j and is the Lagrange multiplier, which arises due to incompressibility. Analogous to Eq. (8), the extra stress due to the deformation for the mixture is .

Let us consider four key structural constituents: elastin, collagen, smooth muscle, and water. Let water be modeled as an inviscid fluid; thus Tw=−pwI (and T̂w=0). Let elastin be modeled as an isotropic material; we employ a neo-Hookean model for elastin

| (20) |

where be is a material parameter. Let muscle be modeled as a transversely isotropic material (i.e., one fiber-family model) with a preferred circumferential direction as

| (21) |

where bm, , and are material parameters. Again we assume that the fibers do not contribute exponentially under compression; thus we set when . Let collagen be modeled with a three fiber-family model

| (22) |

where bc, , and are material parameters; again we set when . Here the collagen fibers are oriented at angles 0 deg and ±αc. We neglect the contribution of the “isotropic” part of Eq. (22); thus, bc ≈ 0. That is, we assume that the collagen fibers are embedded in the amorphous matrix described by the isotropic terms in Eqs. (20) and (21).

Kinematics: Nonuniform constrained mixture

The components of Fj and Cj for inflation and extension are easily calculated as

| (23) |

For elastin and muscle (j=e or m), we will quantify the stretches as

| (24) |

where (Rn)j is the radius and is the axial length of a cylindrical shell for which constituent j is at zero stress (for this material point); is the arc length of this cylindrical shell. Thus, in addition to determining material parameters, one must either prescribe or experimentally quantify the natural configurations (Rn)j and for each constituent. One way to prescribe these natural configurations is to assume that each constituent is present at homeostatic stretches in an in vivo (homeostatic) configuration r=rh and ℓ= ℓh; given these stretches and this loaded geometry, (Rn)j and may be determined via Eq. (24).

For collagen (j=c), we let the current and natural configurations of each fiber-family be described in terms of a fiber angle and a fiber length. Let ωjk and Ωjk be the fiber angle of fiber-family k of constituent j (i.e., collagen) in the current and natural configurations, respectively, and let γjk and Γjk be the lengths of each fiber-family k of constituent j in the current and natural configurations, respectively. Thus, instead of prescribing the natural configuration in terms of (Rn)j and , we will prescribe the natural configuration in terms of Ωjk and Γjk. Let us assume that each fiber k of constituent j is present at homeostatic stretch and a homeostatic fiber orientation ωjk|h in the in vivo (homeostatic) configuration r=rh and ℓ= ℓh. The length of the fiber in the in vivo configuration can be calculated as

| (25) |

The stress-free length of the fiber can then be calculated as

| (26) |

where we emphasize that the reference length of each fiber-family will vary with radial location. Note that this fiber will be stress-free as long as the length of the fiber equals the unloaded length Γjk; thus, the stress-free configuration may be defined at any stress-free fiber orientation angle Ωjk. Let us define the natural configuration, such that when the fiber length is Γjk, the dimensions of the cylindrical shell passing through r=rh with length ℓ = ℓh are such that 2π(Rn)j=(Ln)j. For this case,

| (27) |

where each fiber angle in the reference configuration will vary with radial location.

Given this natural configuration (Γjk, Ωjk), the fiber stretch and fiber angle ωjk in any (loaded) configuration βt are

| (28) |

Thus, given values for λck and ωck via Eq. (28), we can evaluate Eq. (22).

2.3 Microstructurally Motivated Models: Distribution of Fibers

Microscopy reveals that cells and fibrous matrix constituents, such as collagen, exhibit not just a few discrete fiber directions, but rather a continuous distribution of fiber directions. Microscopy also reveals significant variations in the undulation collagen fibers (cf. Ref. [2]) as well as in the lengths of the smooth muscle cells in normal arteries [13]. Thus, we will allow different members of each constituent class to possess different sets of natural configurations and describe the distribution of mass over these different sets of natural configurations via distribution functions.

For elastin and muscle, we adopt the approach of Gleason and Humphrey [14]. Briefly, we assume that constituent j is present in the in vivo state at a homeostatic distribution of stretches . Rather than prescribing the functional form of , we simply prescribe the functional form of the distribution of natural configurations , which results from laying down new material with the distribution of stretches in the (known) loaded configuration. We let be described by a beta probability distribution function, with independent variables R̃ and L̃, as

| (29) |

where , and are shape parameters, B(·,·) is the beta function, , R̄j and L̄j are mean values of the natural configurations, and ΔR̄j and ΔL̄j are the widths of the distribution. If we know the current state (rh, ℓh), we can prescribe the mean natural configurations of the distribution as

| (30) |

where and are the mean values of the preferred homeostatic stretch distribution.

We will consider collagen to be comprised of a distribution of fibers with fiber orientations ω̃ ∈ [0, 90] and fiber stretches λ̃f. Thus, we let

| (31) |

where R̂c(Γ̃, Ω̃) describes how the mass of collagen is distributed over all possible combinations of natural configurations (Γ̃, Ω̃). Each fiber is oriented in the Z̃-Θ̃ plane, , where Ω̃ denotes the angle between the fiber direction and Z̃ axis in the natural configuration, γ is the length of the fiber in the loaded configuration, and Γ̃ is the unloaded length of fibers oriented in the direction Ω̃.

We will let the fibers be laid down at a homeostatic distribution of fiber angles described via a sum of normal distribution functions, given as

| (32) |

where following Eq. (27), ω̃ is related to Ω̃ as

| (33) |

and ω̄p and σp are the mean and standard deviation of normal distribution p. Here p=2, and σ1 = σ2 =10 deg; ω̄1 =0 deg, while ω̄2 was solved along with material and other structural parameters via regression. In addition, we will assume that at each fiber angle, ω̃, the fibers are laid down at a homeostatic distribution of stretches, . As with elastin and smooth muscle, rather than prescribing the distribution of in vivo stretches and then mapping these stretches back to a reference state, we will simply prescribe the distribution of fiber lengths (Γ̃) in the reference state; let this distribution be denoted as B̂ j(Γ̃, Ω̃; r), via a beta distribution function, as

| (34) |

where we recall that ω̃ =ω̃ (Ω̃;s), pj(ω̃) and qj(ω̃) are shape parameters, Γmax(ω̃) and Γmin(ω̃) are the maximum and minimum values of Γ̃ (i.e., B̂j(Γ̃, Ω̃; r)=0 for Γ̃ >Γmax or Γ̃ < Γmin), and B(·,·) is the beta function. We let pj(ω̃)=qj(ω̃)=4.5 and ΔΓ= Γmax − Γmin=0.10.

The distribution of mass over all combinations of fiber angle and fiber stretch may be given as

| (35) |

Note that this distribution function has the properties

| (36) |

Here, we only consider distribution functions that possess symmetry about the r-z plane and the r-θ plane; thus the limits of integration of Ω̃ =0 to π/2 in Eq. (31) represent the first quadrant, which is repeated in the second quadrant (and in the third and fourth quadrants). In Eq. (22), only symmetry about the r-θ plane is required. Note, too, that given symmetry of R̂ j(Γ̃, Ω̃),

| (37) |

Therefore, from Eqs. (22)–(31), we set the limits of integration of Ω̃ =0 to π/2 and multiply by 2.

2.4 Parameter Estimation

Material parameters were determined via a nonlinear regression technique that minimized the error between measured values of P and f and calculated values of P and f from Eqs. (7) and (10) given measured values of outer diameter and length under these measured values of P and f; also unloaded radius, length, and thickness were measured. We employ Eq. (1), with Eq. (6), and specify the in vivo configuration and transmural strains in this configuration to determine F and C. We seek to identify material parameters via nonlinear regression with the minimization function

| (38) |

where

| (39) |

quantifies the difference between experimental data and modeling predictions and penalty(i) is a penalty function that is used to enforce several “side conditions” described further below. Calculations were performed in MATLAB 7.4 using the lsqnonlin subroutine; this subroutine allows the prescription of upper and lower limits on the parameter values. Data were taken between 0 mm Hg and 160 mm Hg for the P-d tests and between 0 mN and 40 mN for the f -ℓ tests; taken together, the three P-d tests and three f -ℓ tests represent n=800–1200 data points.

Penalty set

The microstructural motivation for proposing a mixture based constitutive equation (Eqs. (19)–(22)) is that each constituent (elastin, collagen, muscle, and water) be “structurally significant.” By structurally significant, we mean that each contributes significantly to the overall biomechanical response. Thus, in addition to minimizing the error between experimental data and the model prediction, we also seek a set of parameters that represent well the characteristic responses of each constituent. Simply identifying the material parameters in Eqs. (20)–(22) by minimizing the error function (39) does not ensure that each constituent will contribute significantly to the overall stress. For example, a good fit may occur with be very small; thus, the contribution of elastin to the overall stress would be negligible. To ensure that each constituent is structurally significant, we must impose additional constraints (or penalties) on the error function during parameter estimation. We enforce the constraint that, under modest pressure, the circumferential stress in elastin contributes to at least 30% of the overall stress, and, under high pressure, the circumferential stress in the collagen contributes to at least 75% of the overall stress. Let us impose the following constraints.

- For 59<P<61 mm Hg and 1.79<λz <1.81, let

(40) - For 159<P<161 mm Hg and λz > 1.9, let

(41)

The first constraint (Eq. (40)) ensures that elastin contributes significantly under subphysiological loading. The second constraint (Eq. (41)) ensures that collagen bears much of the load over sup-raphysiological loading. These constraints may be enforced via the penalty function in Eq. (38). For example, if the pressure and stretch are within the loading range specified and , then let

where w is a weighting parameter and i denotes the ith data point.

2.5 Statistical Analysis

Parameters were obtained for each of the models for all of the data sets. Data sets were from three groups of six vessels with culture stretches of , and on day 0 and day 2 of culture. Note that the high stretch only had five complete data sets. An Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was performed using MINITAB to test for differences in parameters between the groups both at day 0 and day 2. Additionally, a repeated measures ANOVA was used to investigate changes within each of the three groups between the two time points. Statistical differences were reported for p<0.05.

3 Results

3.1 Phenomenological Models

Chuong and Fung

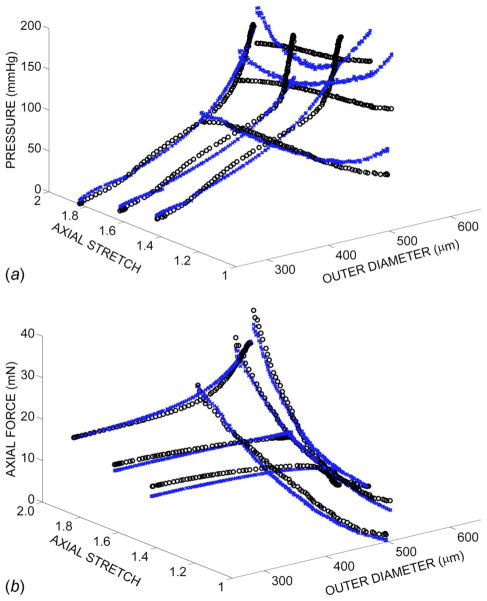

The lower and upper limits of parameter values were set at c ∈ [0,1010] and ci ∈ [0,10] for i=1, …,6. The final fitted parameter values were insensitive to initial parameter guesses. The mean value of the error was 0.085, which provided a reasonably good fit to data (Fig. 1). Statistically significant differences were observed at day 2 between groups cultured at and for parameters c, c2, c4, and c5 (Table 1). In addition, c and c2 differed across the groups cultured at and , and c4 was different between and at day 2. Repeated measures ANOVA showed differences for all parameters in the culture group between day 0 and day 2 and differences in c, c1, c2, c3, and c5 for the group between day 0 and day 2.

Fig. 1.

Pressure (a) and axial force (b) versus outer diameter and axial stretch. The open circles represent the experimental data and the x’s represent the model predictions using the model of Chuong and Fung [7].

Table 1.

Material parameters for the model of Chuong and Fung [7] determined via nonlinear regression

| c (kPa) | c1 | c2 | c3 | c4 | c5 | c6 | Error | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0,

| ||||||||

| 053104_01 | 246 | 0.106 | 0.299 | 0.874 | 0.010 | 0.218 | 0.000 | 0.068 |

| 053104_02 | 140 | 0.077 | 0.433 | 1.158 | 0.011 | 0.278 | 0.000 | 0.067 |

| 061604_01 | 312 | 0.186 | 0.201 | 0.891 | 0.000 | 0.114 | 0.053 | 0.072 |

| 080304_02 | 319 | 0.055 | 0.219 | 0.339 | 0.000 | 0.065 | 0.000 | 0.076 |

| 100504_01 | 336 | 0.069 | 0.165 | 0.314 | 0.000 | 0.051 | 0.020 | 0.081 |

| 100504_02 | 333 | 0.073 | 0.175 | 0.285 | 0.000 | 0.036 | 0.027 | 0.099 |

| Mean | 281d | 0.094d | 0.249d | 0.644d | 0.004d | 0.127d | 0.017d | 0.077 |

| SD | 76.4 | 0.048 | 0.102 | 0.376 | 0.005 | 0.099 | 0.021 | 0.012 |

| Day 2,

| ||||||||

| 053104_01 | 82.9 | 0.425 | 0.933 | 3.160 | 0.136 | 0.831 | 0.348 | 0.091 |

| 053104_02 | 57.9 | 0.287 | 0.915 | 2.718 | 0.092 | 0.728 | 0.229 | 0.092 |

| 061604_01 | 85.1 | 0.307 | 0.603 | 2.449 | 0.070 | 0.520 | 0.347 | 0.086 |

| 080304_02 | 62.6 | 0.142 | 0.878 | 1.758 | 0.025 | 0.447 | 0.000 | 0.098 |

| 100504_01 | 58.9 | 0.150 | 0.899 | 1.190 | 0.011 | 0.400 | 0.000 | 0.110 |

| 100504_02 | 56.3 | 0.379 | 0.744 | 1.518 | 0.062 | 0.286 | 0.188 | 0.093 |

| Mean | 67.3a,d | 0.282d | 0.829a,d | 2.132d | 0.066a,c,d | 0.535a,d | 0.185d | 0.095 |

| SD | 13.1 | 0.116 | 0.129 | 0.762 | 0.045 | 0.206 | 0.157 | 0.008 |

| Day 0,

| ||||||||

| 060504_02 | 486 | 0.050 | 0.162 | 0.209 | 0.003 | 0.040 | 0.000 | 0.095 |

| 060804_02 | 991 | 0.047 | 0.093 | 0.088 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.078 |

| 092604_01 | 321 | 0.067 | 0.222 | 0.273 | 0.007 | 0.069 | 0.000 | 0.062 |

| 092604_02 | 126 | 0.113 | 0.665 | 2.310 | 0.044 | 0.624 | 0.044 | 0.068 |

| 100804_01 | 411 | 0.045 | 0.167 | 0.185 | 0.001 | 0.036 | 0.000 | 0.109 |

| 100804_02 | 295 | 0.049 | 0.204 | 0.195 | 0.000 | 0.039 | 0.005 | 0.083 |

| Mean | 438e | 0.062e | 0.252e | 0.543e | 0.009 | 0.135e | 0.008 | 0.083 |

| SD | 297 | 0.026 | 0.207 | 0.868 | 0.017 | 0.241 | 0.018 | 0.017 |

| Day 2,

| ||||||||

| 060504_02 | 143 | 0.199 | 0.529 | 1.113 | 0.011 | 0.208 | 0.103 | 0.091 |

| 060804_02 | 185 | 0.175 | 0.458 | 0.742 | 0.020 | 0.148 | 0.057 | 0.080 |

| 092604_01 | 118 | 0.111 | 0.639 | 0.668 | 0.000 | 0.153 | 0.000 | 0.072 |

| 092604_02 | 37.4 | 0.216 | 1.275 | 3.706 | 0.019 | 0.908 | 0.080 | 0.074 |

| 100804_01 | 70.8 | 0.153 | 0.847 | 1.526 | 0.018 | 0.417 | 0.000 | 0.088 |

| 100804_02 | 54.3 | 0.196 | 0.750 | 0.620 | 0.000 | 0.063 | 0.000 | 0.089 |

| Mean | 101b,e | 0.175e | 0.750b,e | 1.396e | 0.011c | 0.316e | 0.040 | 0.082 |

| SD | 57.0 | 0.038 | 0.294 | 1.183 | 0.009 | 0.313 | 0.046 | 0.008 |

| Day 0,

| ||||||||

| 052804_01 | 323 | 0.122 | 0.210 | 0.612 | 0.008 | 0.119 | 0.000 | 0.061 |

| 052804_02 | 457 | 0.017 | 0.269 | 0.338 | 0.011 | 0.161 | 0.000 | 0.060 |

| 061204_01 | 270 | 0.128 | 0.281 | 1.043 | 0.031 | 0.244 | 0.085 | 0.074 |

| 061204_02 | 397 | 0.070 | 0.182 | 0.272 | 0.000 | 0.039 | 0.010 | 0.081 |

| 093004_01 | 276 | 0.075 | 0.219 | 0.412 | 0.000 | 0.082 | 0.000 | 0.067 |

| Mean | 345 | 0.082 | 0.232 | 0.535 | 0.010 | 0.129 | 0.019 | 0.069 |

| SD | 80.7 | 0.045 | 0.042 | 0.311 | 0.013 | 0.078 | 0.037 | 0.009 |

| Day 2,

| ||||||||

| 052804_01 | 381 | 0.164 | 0.190 | 0.677 | 0.000 | 0.072 | 0.121 | 0.135 |

| 052804_02 | 132 | 0.154 | 0.469 | 1.788 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.183 | 0.078 |

| 061204_01 | 92.9 | 0.291 | 0.675 | 2.056 | 0.000 | 0.303 | 0.311 | 0.147 |

| 061204_02 | 332 | 0.086 | 0.227 | 0.272 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.064 | 0.095 |

| 093004_01 | 247 | 0.047 | 0.306 | 0.249 | 0.000 | 0.053 | 0.024 | 0.081 |

| Mean | 237a,b | 0.148 | 0.373a,b | 1.008 | 0.000a | 0.086a | 0.141 | 0.107 |

| SD | 124 | 0.093 | 0.200 | 0.857 | 0.000 | 0.126 | 0.113 | 0.032 |

Indicates p<0.05 when comparing 1.65 and 1.95 on day 2.

Indicates p<0.05 when comparing 1.80 and 1.95 on day 2.

Indicates p<0.05 when comparing 1.65 and 1.80 on day 2.

Indicates p<0.05 when comparing day 0 and day 2 for the 1.65 group.

Indicates p<0.05 when comparing day 0 and day 2 for the 1.80 group.

Four fiber-family model

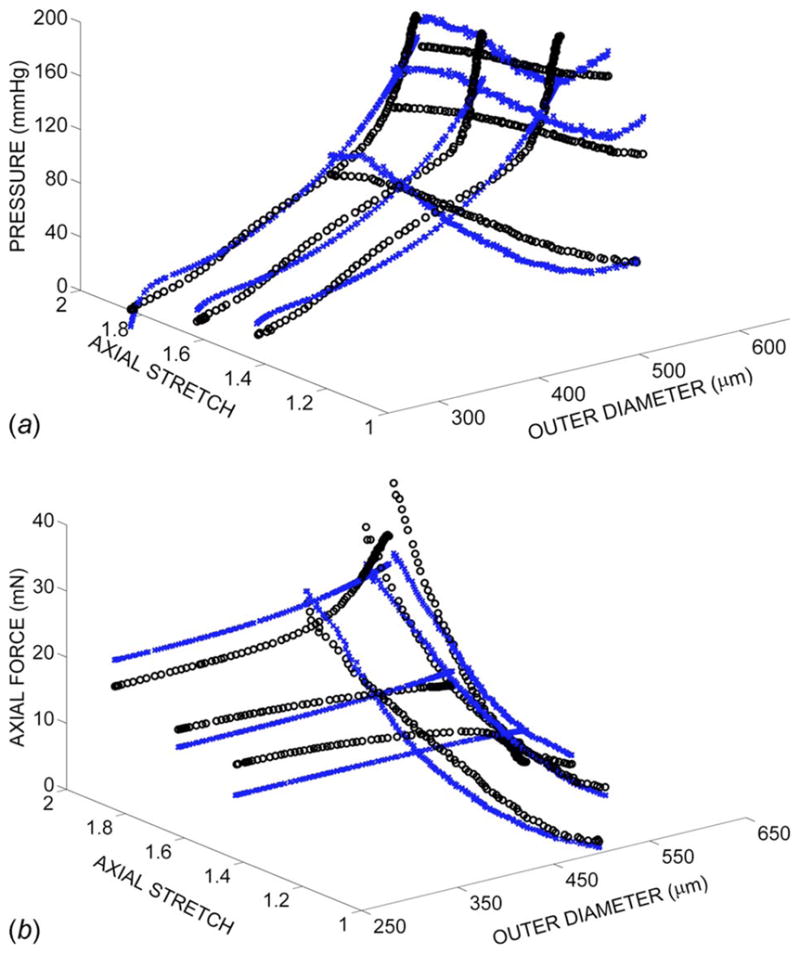

The lower and upper limits of the parameters were b and , and α ∈ [5 deg,85 deg]. Final parameter values were insensitive to initial guesses. The model provided a good fit to data with a mean value of the error=0.055 (Fig. 2). For all vessels at all culture times the fiber-family model provided a better fit than the Fung model (Table 2); this finding is consistent with that of Gleason et al. (15). A significant difference was seen for at day 2 across the low ( ) and high ( ) stretch culture groups and across day 0 and day 2 for low stretch culture group. Additionally, the parameter is significantly different across day 0 and day 2 for the cultured vessels.

Fig. 2.

Pressure (a) and axial force (b) versus outer diameter and axial stretch. The open circles represent the experimental data and the x’s represent the model predictions using the four-fiber model.

Table 2.

Material parameters for the four fiber-family model determined via nonlinear regression

| b (kPa) | (kPa) | (kPa) | (kPa) | α | Error | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0,

| ||||||||||||

| 053104_01 | 18.3 | 9.1 | 0.076 | 28.5 | 0.036 | 0.0068 | 0.986 | 32.5 | 0.037 | |||

| 053104_02 | 16.2 | 1.7 | 0.102 | 28.1 | 0.047 | 0.0072 | 0.922 | 31.6 | 0.034 | |||

| 061604_01 | 39.5 | 0.5 | 0.828 | 12.7 | 0.096 | 0.0000 | 2.463 | 49.4 | 0.038 | |||

| 080304_02 | 11.6 | 4.9 | 0.052 | 36.1 | 0.015 | 0.0001 | 1.373 | 31.6 | 0.046 | |||

| 100504_01 | 6.4 | 8.2 | 0.041 | 28.3 | 0.010 | 0.0000 | 1.627 | 30.7 | 0.054 | |||

| 100504_02 | 7.2 | 8.0 | 0.043 | 32.1 | 0.009 | 0.0000 | 1.555 | 37.5 | 0.065 | |||

| Mean | 16.5 | 5.4 | 0.191 | 27.6 | 0.035 | 0.0023b | 1.488 | 35.5 | 0.046 | |||

| SD | 12.2 | 3.6 | 0.313 | 8.0 | 0.033 | 0.0036 | 0.559 | 7.2 | 0.012 | |||

| Day 2,

| ||||||||||||

| 053104_01 | 20.3 | 6.7 | 0.389 | 33.7 | 0.094 | 0.4074 | 1.063 | 35.0 | 0.064 | |||

| 053104_02 | 11.9 | 3.0 | 0.274 | 25.4 | 0.089 | 0.2354 | 0.947 | 32.7 | 0.064 | |||

| 061604_01 | 12.5 | 3.6 | 0.246 | 28.7 | 0.036 | 0.0119 | 1.228 | 35.3 | 0.044 | |||

| 080304_02 | 13.9 | 1.9 | 0.152 | 39.4 | 0.046 | 0.0829 | 0.991 | 26.6 | 0.051 | |||

| 100504_01 | 2.7 | 4.7 | 0.079 | 40.7 | 0.028 | 0.0941 | 0.973 | 25.5 | 0.071 | |||

| 100504_02 | 9.1 | 7.7 | 0.214 | 32.1 | 0.037 | 0.2433 | 0.938 | 32.3 | 0.063 | |||

| Mean | 11.7 | 4.6 | 0.226 | 33.3 | 0.055 | 0.1792a,b | 1.023 | 31.2 | 0.059 | |||

| SD | 5.8 | 2.2 | 0.106 | 5.9 | 0.029 | 0.1441 | 0.110 | 4.2 | 0.010 | |||

| Day 0,

| ||||||||||||

| 060504_02 | 13.0 | 7.8 | 0.037 | 37.1 | 0.024 | 0.0022 | 0.950 | 41.1 | 0.039 | |||

| 060804_02 | 16.8 | 15.7 | 0.001 | 42.2 | 0.023 | 0.0010 | 1.263 | 63.8 | 0.043 | |||

| 092604_01 | 11.1 | 8.1 | 0.035 | 35.2 | 0.028 | 0.0042 | 0.951 | 40.2 | 0.040 | |||

| 092604_02 | 19.4 | 5.8 | 0.064 | 37.6 | 0.060 | 0.2072 | 0.687 | 29.9 | 0.048 | |||

| 100804_01 | 8.2 | 7.8 | 0.025 | 38.4 | 0.000 | 0.0000 | 2.073 | 13.8 | 0.090 | |||

| 100804_02 | 3.9 | 6.8 | 0.016 | 34.5 | 0.015 | 0.0001 | 1.148 | 35.1 | 0.055 | |||

| Mean | 12.1 | 8.7 | 0.030 | 37.5 | 0.025c | 0.0358 | 1.179 | 37.3 | 0.053 | |||

| SD | 5.6 | 3.5 | 0.022 | 2.8 | 0.020 | 0.0840 | 0.481 | 16.4 | 0.019 | |||

| Day 2,

| ||||||||||||

| 060504_02 | 17.4 | 4.2 | 0.197 | 39.9 | 0.063 | 0.0021 | 1.635 | 36.6 | 0.057 | |||

| 060804_02 | 25.9 | 0.6 | 0.591 | 38.5 | 0.065 | 0.0389 | 1.227 | 36.3 | 0.046 | |||

| 092604_01 | 17.1 | 0.5 | 0.216 | 39.0 | 0.096 | 0.0266 | 1.072 | 33.0 | 0.045 | |||

| 092604_02 | 3.6 | 9.9 | 0.036 | 43.3 | 0.076 | 0.1153 | 0.968 | 24.3 | 0.049 | |||

| 100804_01 | 3.3 | 10.6 | 0.023 | 44.4 | 0.019 | 0.0500 | 1.189 | 24.2 | 0.058 | |||

| 100804_02 | 4.8 | 7.6 | 0.054 | 39.0 | 0.035 | 0.0530 | 1.045 | 27.0 | 0.055 | |||

| Mean | 12.0 | 5.6 | 0.186 | 40.7 | 0.059c | 0.0476 | 1.189 | 30.2 | 0.052 | |||

| SD | 9.4 | 4.5 | 0.215 | 2.5 | 0.028 | 0.0380 | 0.238 | 5.8 | 0.006 | |||

| Day 0,

| ||||||||||||

| 052804_01 | 26.9 | 6.5 | 0.203 | 21.1 | 0.052 | 0.0003 | 1.698 | 41.4 | 0.039 | |||

| 052804_02 | 3.0 | 5.7 | 0.000 | 60.4 | 0.000 | 0.0828 | 0.605 | 20.5 | 0.037 | |||

| 061204_01 | 21.0 | 6.4 | 0.144 | 26.7 | 0.041 | 0.0018 | 1.286 | 35.8 | 0.040 | |||

| 061204_02 | 17.7 | 3.3 | 0.136 | 32.5 | 0.028 | 0.0000 | 1.727 | 38.6 | 0.047 | |||

| 093004_01 | 17.0 | 2.2 | 0.136 | 25.3 | 0.033 | 0.0001 | 1.355 | 36.0 | 0.051 | |||

| Mean | 17.1 | 4.8 | 0.124 | 33.2 | 0.031 | 0.0170 | 1.334 | 34.4 | 0.043 | |||

| SD | 8.8 | 1.9 | 0.075 | 15.7 | 0.020 | 0.0368 | 0.453 | 8.1 | 0.006 | |||

| Day 2,

| ||||||||||||

| 052804_01 | 23.0 | 3.4 | 0.358 | 21.8 | 0.085 | 0.0000 | 4.795 | 52.3 | 0.116 | |||

| 052804_02 | 16.4 | 2.6 | 0.117 | 43.2 | 0.097 | 0.0016 | 1.400 | 40.2 | 0.064 | |||

| 061204_01 | 12.4 | 2.8 | 0.230 | 41.3 | 0.045 | 0.0018 | 1.597 | 29.5 | 0.087 | |||

| 061204_02 | 6.4 | 7.8 | 0.021 | 40.0 | 0.055 | 0.0001 | 1.400 | 61.5 | 0.065 | |||

| 093004_01 | 2.6 | 4.5 | 0.020 | 42.3 | 0.026 | 0.0000 | 1.738 | 29.3 | 0.059 | |||

| Mean | 12.1 | 4.2 | 0.149 | 37.7 | 0.062 | 0.0007a | 2.186 | 42.6 | 0.078 | |||

| SD | 8.0 | 2.1 | 0.145 | 9.0 | 0.029 | 0.0009 | 1.466 | 14.2 | 0.024 | |||

p<0.05 when comparing 1.65 and 1.95 at day 2.

p<0.05 when comparing day 0 and day 2 for the 1.65 group.

p<0.05 when comparing day 0 and day 2 for the 1.80 group.

3.2 Microstructurally Motivated Models: A Discrete Set of Fibers

We considered several variants of the rule-of-mixtures model, discussed separately below. In all cases, we prescribed the lower and upper limits of the parameters as be, bm, , and , and , and Ωc2|h∈ [5 deg,85 deg]. Final parameter values were insensitive to initial guesses. For the models that included material nonuniformity, unless otherwise noted, we prescribed the limits (Rn)e/Rn ∈ [0.8,0.95], (Ln)e/Ln ∈ [0.8,0.95], (Rn)m/Rn ∈ [0.95,1.1], (Ln)m/Ln ∈ [0.95,1.1], and λc1|h ∈ [1.0,1.876]. Note that these limits force elastin to be in tension in the stress-free state, collagen to be in compression in the stress-free state, and muscle may be in tension or compression. Rather than tabulating statistical differences in parameters for each variation of the rule-of-mixtures model, we instead present parameters from representative vessels from day 0 and day 2 at each culture stretch to allow comparison of the different model variations (Table 3).

Table 3.

Material parameters for representative data for various versions of the rule-of-mixtures constitutive model

| be (kPa) | bm (kPa) | (kPa) | (kPa) | (kPa) | ωc2 | Re | Rm | λc | Error | Penalty | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0,

(061604_01)

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| ROM A (no pen) | 214.9 | 163.4 | 165.0 | 0.034 | 96.2 | 0.107 | 0.0 | 1.895 | 63.2 | – | – | – | – | – | 0.041 | – | |||||

| ROM A | 379.7 | 158.0 | 0.0 | 0.000 | 59.4 | 0.152 | 1.09 | 0.977 | 65.6 | – | – | – | – | – | 0.051 | 0.002 | |||||

| ROM B | 379.8 | 157.2 | 0.0 | 0.008 | 1983 | 1.171 | 102.3 | 5.267 | 65.2 | 0.96 | 0.80 | 1.10 | 0.99 | 1.273 | 0.051 | 0.002 | |||||

| ROM C | 504.9 | 170.1 | 0.0 | 0.000 | 388.6 | 4.331 | – | – | 60.0 | 1.00 | 0.80 | 1.10 | 0.95 | 1.222 | 0.081 | 0.006 | |||||

| Fiber | 281.7 | 130.4 | 45.1 | 0.000 | 2345 | 0.751 | 240.0 | 3.436 | 64.7 | 0.92 | 0.80 | 1.10 | 0.95 | 1.303 | 0.056 | 0.002 | |||||

| Day 2,

(061604_01)

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| ROM A (no pen) | 104.0 | 69.3 | 40.5 | 0.246 | 191.5 | 0.036 | 0.1 | 1.228 | 35.3 | – | – | – | – | – | 0.044 | – | |||||

| ROM A | 148.5 | 16.7 | 37.3 | 0.060 | 114.8 | 0.136 | 5.4 | 0.570 | 49.4 | – | – | – | – | – | 0.089 | 0.001 | |||||

| ROM B | 152.9 | 28.6 | 6.7 | 0.702 | 287.5 | 0.153 | 8.9 | 0.438 | 47.7 | 1.00 | 0.80 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 1.876 | 0.086 | 0.001 | |||||

| ROM C | 148.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.341 | 59.7 | 0.361 | – | – | 36.4 | 1.00 | 0.80 | 1.10 | 1.09 | 1.760 | 0.129 | 0.006 | |||||

| Fiber | 61.3 | 12.7 | 88.9 | 0.022 | 1700 | 0.548 | 403.0 | 0.985 | 46.8 | 0.90 | 0.80 | 1.10 | 0.95 | 1.433 | 0.101 | 0.008 | |||||

| Day 2,

(100804_02)

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| ROM A (no pen) | 37.3 | 24.3 | 86.1 | 0.052 | 262.2 | 0.034 | 0.4 | 1.046 | 27.0 | – | – | – | – | – | 0.055 | – | |||||

| ROM A | 105.3 | 9.2 | 13.3 | 0.158 | 107.4 | 0.205 | 11.5 | 0.446 | 37.8 | – | – | – | – | – | 0.088 | 0.001 | |||||

| ROM B | 104.7 | 35.8 | 15.2 | 0.302 | 336.9 | 0.194 | 12.0 | 0.401 | 39.1 | 1.00 | 0.81 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 1.876 | 0.088 | 0.001 | |||||

| ROM C | 113.4 | 0.0 | 10.5 | 0.401 | 59.4 | 0.329 | – | – | 28.1 | 1.00 | 0.80 | 1.10 | 1.09 | 1.809 | 0.135 | 0.004 | |||||

| Fiber | 73.8 | 2.6 | 78.0 | 0.000 | 1878 | 0.967 | 407.0 | 1.248 | 39.8 | 0.95 | 0.80 | 1.10 | 0.95 | 1.406 | 0.113 | 0.010 | |||||

| Day 2,

(052804_02)

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| ROM A (no pen) | 136.5 | 91.0 | 29.2 | 0.117 | 287.8 | 0.097 | 0.0 | 1.400 | 40.2 | – | – | – | – | – | 0.064 | – | |||||

| ROM A | 134.2 | 83.1 | 0.0 | 0.000 | 225.0 | 0.153 | 6.8 | 0.348 | 53.3 | – | – | – | – | – | 0.071 | 0.000 | |||||

| ROM B | 208.2 | 38.3 | 0.0 | 0.000 | 725.3 | 0.151 | 8.3 | 0.368 | 55.3 | 1.00 | 0.80 | 1.07 | 0.95 | 1.876 | 0.070 | 0.000 | |||||

| ROM C | 136.9 | 69.6 | 0.3 | 0.888 | 115.9 | 0.261 | – | – | 27.8 | 0.95 | 0.80 | 1.10 | 0.95 | 1.783 | 0.122 | 0.009 | |||||

| Fiber | 127.2 | 25.6 | 1.3 | 0.576 | 1730 | 0.352 | 371.7 | 0.244 | 44.1 | 0.95 | 0.80 | 1.10 | 0.95 | 1.584 | 0.087 | 0.000 | |||||

ROM A: Uniform four-fiber: One muscle fiber, three collagen fibers (eight material parameters, one structural parameter)

Consider the rule-of-mixtures equations proposed above, but assume that the material is uniform; thus, (Rn)e=(Rn)c=(Rn)m=Rn and . For this case, , and

| (42) |

Notice that this model reduces to the four fiber-family model described above; if b=(φebe+φmbm), , and , then Eq. (42) is identical to Eq. (16), determined from a four fiber-family model. If we let be =b/(2φe) and bm=b/(2φm), then the identical fits as above with the four fiber-family model will be achieved. The mean error for the four vessels considered was 0.055, which was equal to the mean of all vessels for the four fiber-family model; thus, these four vessels are considered representative.

We also enforced constraints (40) and (41) via the penalty method for this rule-of-mixtures model. The mean value of the error was 0.084 for the four vessels considered (Table 3), which provided a worse fit than the ROM A without penalties (i.e., the four fiber-family model), but equally well as the Fung model; these findings are consistent across all vessels (not shown). The average penalty for these four vessels was 0.001; thus, the penalty criteria were nearly, but not completely, satisfied.

ROM B. Nonuniform four-fiber: One muscle fiber, three collagen fibers (eight material parameters, seven structural parameter)

Next, consider the same functional form of the constitutive equation as in (ROM A), but let the material be nonuniform. That is, let (Rn)e/Rn, (Rn)m/Rn, , λc1|h = λc2|h, and ωc2|h be free (structural) parameters that may be determined via nonlinear regression along with the eight material parameters. Note that we set ωc1|h =0 deg and . First, we let the upper and lower limits for the structural parameters of elastin be (Rn)e/Rn ∈ [0.8,1.0] and (Ln)e/Ln ∈ [0.8,1.0]; these regressions are referred to as ROM B1. The mean value of the error was 0.083 for the four vessels; the average penalty was 0.001. Thus, adding material nonuniformity provided little to no increase in the goodness of fit. Notice, too, that several of the structural parameters obtained via regression were at, or very near, the upper or lower limits prescribed for the regression. Next, we set the upper and lower limits for the structural parameters of elastin as (Rn)e/Rn ∈ [0.8,0.95] and (Ln)e/Ln ∈ [0.8,0.95] (denoted ROM B2); thus, elastin is required to be in tension in the mixture reference state. The mean value of the error equaled 0.100 for the four vessels, and the average penalty was 0.002. Thus, by simply requiring that elastin be in tension, there was a significant reduction in the goodness of fit. Notice, too, that whereas was at its upper limit of 1.876 for all four vessels in ROM B1, the average value for was 1.46 in ROM B2.

ROM C. Nonuniform four-fiber: One muscle fiber, three collagen fibers (six material parameters, six structural parameter)

Here we consider the same nonuniform model at ROM B, but let and ; that is, we let the material properties of the fibers oriented in the ωc1|h direction equal those oriented in the ±ωc2|h direction. The mean value of the error was 0.152 for the four vessels considered, and the average penalty was 0.006. Thus, requiring the collagen fibers in the axial and off-axis directions to have the same material parameters significantly reduced the goodness of fit and satisfaction of the penalty criteria.

3.3 Microstructurally Motivated Models: Distribution of Fibers

For the fiber distribution model, let R̄e/Rn, R̄m/Rn, L̄e/Ln, L̄m/Ln, λ̄c1|h = λ̄c2|h, and ω̄c2|h be free (structural) parameters that may be determined via nonlinear regression along with the eight material parameters and let and . We used the values from ROM B2 as initial guesses for this fiber distribution. The mean value of the error equaled 0.098 for the four vessels and the average penalty was 0.005. The addition of a distribution of fibers did not appear to greatly change the goodness of fit of the model as the error values for the model were similar to ROM B2, which had the same number of free parameters. In this analysis, we fixed the width of the distribution functions by prescribing σp and ΔΓ for the collagen distribution and ΔRj and ΔLj for the elastin and muscle distribution. These parameters, however, could be adjusted to improve the goodness of fit. Ultimately, however, the utility of such microstructurally motivated model is to quantify the fiber distribution directly from data (cf. Refs. [16,17]), rather than prescribing the fiber distribution functions, as done in this paper.

4 Discussion

Mechanotransduction of mechanical signals to cellular responses plays a central role in maintaining tissue homeostasis, as well as the development of numerous pathologies. Fundamental to quantifying a mechanosensitive biological response of a cell within a tissue is the quantification of the mechanical environment in a local neighborhood around that cell. When a good approximation of the local mechanical environment (e.g., in terms of stress and strain) is made, only then can a correlation be rightfully made between local mechanical stimuli and local biological response. Thus, there is a pressing need to better quantify the local mechanical environment in blood vessels and how this local mechanical environment evolves as the tissue grows and remodels. Toward this end, we have quantified material and structural parameters for several constitutive models for mouse carotid arteries exposed to altered axial extension in organ culture.

We found that the model of Chuong and Fung [7] provided a good fit to data. However, motivated by the fact that blood vessels have smooth muscle cells oriented circumferentially and collagen fibers oriented axially and distributed at off-axis angles, we considered a microstructurally motivated four fiber-family model. In all cases the four-fiber model provided a better fit to data than did the model of Chuong and Fung [7]. Indeed, even two fiber-family models, with fibers oriented at ±α, have been shown to provide good agreement with data [3]. A four fiber-family model has been shown to provide a better fit to data from mouse vessels than a two fiber-family and a slightly better fit than a three fiber-family model [18], at the cost of additional material parameters. For the sake of improving the fit, the cost of additional parameters when using a four fiber-family over a two or three fiber-family model may not be well justified. However, when attempting to ascribe physical meaning to each fiber-family (e.g., by allowing one fiber-family to represent smooth muscle, another to represent axially oriented collagen, and others to represent collagen oriented off axis), the number of fiber-families should be chosen based on observations of the microstructure.

Although our goal in considering a four fiber-family model was to ascribe each fiber-family to a key structural constituent observed via microscopy, we found that simply performing nonlinear regression did not ensure that each fiber-family (i.e., structural constituent) contributed significantly to the mechanical response. Rather, it was necessary to employ a penalty method to ensure that each constituent had a significant contribution. Although these penalties reduced the goodness of fit compared with the nonpenalized fits, the overall goodness of fit with the penalties included was, in many cases, still equal to the fits obtained via the model of Chuong and Fung [7]; thus, fits that required each constituent be structurally significant still produced a model with reasonable agreement with data. We also found that allowing the stress-free states (or homeostatic stretches) of each constituent to be structural parameters that are solved via regression did not significantly improve model fits. Importantly, however, although this material nonuniformity did not play a significant role in improving the fit of data to our models, tracking the evolution of stress-free states of individual constituents plays a key role in quantifying microstructurally motivated models for tissue growth and remodeling [14,19,8].

Since the classic paper by Roach and Burton [11] it has been thought that elastin plays a key role in the mechanical behavior over low loads and collagen dominates the mechanical behavior over high loads. Brankov et al. [1] also suggested that elastin is under a higher strain in vivo than is collagen. Based on these observations, we imposed penalties and upper and lower limits on structural parameters that enforced these general observations. Although the imposition of these penalties and limits results in a reduction in the goodness of fit, we submit that such criteria are critical when assigning physical meaning to material and structural parameters.

Limitations of the constitutive modeling originate from the adopted assumptions. First, we modeled the mouse carotid artery as a homogeneous mixture. It is clear, however, that these vessels have a thin intima consisting of an endothelial cell monolayer on a basement membrane, a media consisting of smooth muscle, elastin, and collagen, and an adventitia dominated by fibroblasts and collagen; thus vessels are heterogeneous. Unfortunately, sufficient data are not available on the distribution of the key structural constituents and how the content and organization of these constituents evolve during remodeling to altered axial stretch in this ex vivo setting. Although these data are not currently available, as data become available, the structurally motivated models are capable of accounting for vessel heterogeneity by incorporating experimentally observable spatial and temporal variations in structural parameters. Second, because the opening angle was not measured in Ref. [5], we assumed that the strain was uniform across the wall in the in vivo configuration; this assumption may be tested as data on the evolution of opening angle during stretch-induced remodeling become available. Third, and more fundamental, is the assumption that the overall stress is given as the sum of the stresses borne by the individual constituents in the fiber-family and rule-of-mixtures models, thus, excluding the contribution of constituent-to-constituent interactions. Ultimately, incorporation of such interactions will provide important insights toward mechanobiology; however, sufficient data are not yet available to motivate reasonable functional forms for such constitutive equations. Finally, we model the tissue as a constrained mixture; thus, each constituent is constrained to follow the motion of the tissue on the whole; this need not be (and likely is not) the case. To overcome all of these limitations, there is a need for data that quantifies the spatial and temporal variations of constituent content and organization with remodeling and mechanical loading.

In conclusion, we have identified material (and structural) parameters for phenomenological and microstructural models of mouse common carotid arteries exposed to altered axial extension, ex vivo. We have identified models with parameters that provide good agreement with data, while ascribing physical and microstructural meaning to fiber-families that are associated with the underlying microstructural content and organization of the tissue. Although we made several assumptions (e.g., homogeneity, uniform strain in vivo, etc.), as data become available these assumptions may be relaxed. Through the application of new imaging strategies, experimental quantification of spatial and temporal variations in microstructural parameters promises to yield models with broader capabilities to predict the evolution of mechanical behavior during growth and remodeling associated with physiological and pathophysiological processes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by NIH Grant Nos. HL-085822 and T32-GM008433; we gratefully acknowledge this support.

Contributor Information

Laura Hansen, Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA 30332.

William Wan, George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA 30332.

Rudolph L. Gleason, Email: rudy.gleason@me.gatech.edu, Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering, George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering, and Petite Institute for Bioengineering and Bioscience, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA 30332

References

- 1.Brankov G, Rachev AI, Stoychev S. A Composite Model of Large Blood Vessels. In: Brankov G, editor. Mechanics of Biological Solid: Proceedings of the Euromech Colloquium. Bulgarian Academy of Sciences; Varna, Bulgaria: 1975. pp. 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lanir Y. Constitutive Equations for Fibrous Connective Tissues. J Biomech. 1983;16:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(83)90041-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Holzapfel GA, Gasser TC, Ogden RW. A New Constitutive Framework for Arterial Wall Mechanics and a Comparative Study of Material Models. J Elast. 2000;61:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zulliger MA, Fridez P, Hayashi K, Stergiopulos N. A Strain Energy Function for Arteries Accounting for Wall Composition and Structure. J Biomech. 2004;37:989–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2003.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gleason RL, Wilson E, Humphrey JD. Biaxial Biomechanical Adaptations of Mouse Carotid Arteries Cultured at Altered Axial Extension. J Biomech. 2007;40:766–776. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2006.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baek S, Gleason RL, Rajagopal KR, Humphrey JD. Theory of Small on Large in Computations of Fluid-Solid Interactions in Arteries. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2007;196:3070–3078. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chuong CJ, Fung YC. On Residual Stress in Arteries. ASME J Biomech Eng. 1986;108:189–192. doi: 10.1115/1.3138600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gleason RL, Taber LA, Humphrey JD. A 2-D Model of Flow-Induced Alterations in the Geometry, Structure, and Properties of Carotid Arteries. ASME J Biomech Eng. 2004;126:371–381. doi: 10.1115/1.1762899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Humphrey JD. Cardiovascular Solid Mechanics: Cells, Tissues, Organs. Springer-Verlag; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spencer AJM. Constitutive Theory for Strongly Anisotropic Solids. In: Spencer AJM, editor. Continuum Theory of the Mechanics of Fibre-Reinforced Composites (CISM Courses and Lectures Vol. 282) Springer-Verlag; Wien: 1984. pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roach M, Burton A. The Reason for the Shape of the Distensibility Curves of Arteries. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1957;35:681–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Azeloglu EU, Albro MB, Thimmappa VA, Ateshian GA, Costa KD. Heterogeneous Transmural Proteoglycan Distribution Provides a Mechanism for Regulating Residual Stresses in the Aorta. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294(3):H1197–H1205. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01027.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martinez-Lemus LA, Hill MA, Bolz SS, Pohl U, Meininger GA. Acute Mechanoadaptation of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells in Response to Continuous Arteriolar Vasoconstriction: Implications for Functional Remodeling. FASEB J. 2004;18(6):708–710. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0634fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gleason RL, Humphrey JD. A 2-D Constrained Mixture Model for Arterial Adaptations to Large Changes in Flow, Pressure, and Axial Stretch. Math Med Biol. 2005;22(4):347–369. doi: 10.1093/imammb/dqi014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gleason RL, Dye WW, Wilson E, Humphrey JD. Quantification of the Mechanical Behavior of Carotid Arteries From Wild-Type, Dystrophin-Deficient, and Sarcoglycan-Delta Knockout Mice. J Biomech. 2008;41(15):3213–3218. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gleason RL, Wan W. Theory and Experiments for Mechanically-Induced Remodeling of Tissue Engineered Blood Vessels. Adv Sci Technol. 2008;57:226–234. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wicker B, Hutchens H, Wu Q, Yeh A, Humphrey J. Normal Basilar Artery Structure and Biaxial Mechanical Behavior. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Eng. 2008;11(5):539–551. doi: 10.1080/10255840801949793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zeinali-Davarani S, Choi J, Baek S. On Parameter Estimation for Biaxial Mechanical Behavior of Arteries. J Biomech. 2009;42(4):524–530. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Humphrey JD, Rajagopal KR. A Constrained Mixture Model for Growth and Remodeling of Soft Tissues. Math Models Meth Appl Sci. 2002;12(3):407–430. [Google Scholar]