Abstract

Objectives. We examined the associations of overall and age-specific suicide rates with business cycles from 1928 to 2007 in the United States.

Methods. We conducted a graphical analysis of changes in suicide rates during business cycles, used nonparametric analyses to test associations between business cycles and suicide rates, and calculated correlations between the national unemployment rate and suicide rates.

Results. Graphical analyses showed that the overall suicide rate generally rose during recessions and fell during expansions. Age-specific suicide rates responded differently to recessions and expansions. Nonparametric tests indicated that the overall suicide rate and the suicide rates of the groups aged 25 to 34 years, 35 to 44 years, 45 to 54 years, and 55 to 64 years rose during contractions and fell during expansions. Suicide rates of the groups aged 15 to 24 years, 65 to 74 years, and 75 years and older did not exhibit this behavior. Correlation results were concordant with all nonparametric results except for the group aged 65 to 74 years.

Conclusions. Business cycles may affect suicide rates, although different age groups responded differently. Our findings suggest that public health responses are a necessary component of suicide prevention during recessions.

Suicidal behavior and its consequences are major public health issues for our society. In 2007, suicide ranked as the 11th leading cause of death in the United States and was responsible for 34 598 deaths.1 Suicide is influenced by medical, psychological, social, cultural, and economic factors. Some of the earliest systematic studies of suicide, which came from the field of sociology, examined the association of suicide rates with economic crisis.2 However, these studies were limited in scope.

As the US economy is facing its biggest challenge since the Great Depression and economic crisis has hit many areas, suicide cases associated with financial distress are widely reported in the news media.3–6 Suicide studies focusing on economic crisis, which are typically event-based, are meager and give mixed results. Although suicides increased rapidly in the United States7 during the Great Depression and in Korea,8–10 Japan,10 and Hong Kong10 after the outbreak of the Southeast Asian economic crisis, the suicide rate declined during times of economic crisis in Finland,11 Sweden,11 and Geneva, Switzerland,12 and the attempted-suicide rate remained stable in times of economic crisis in Helsinki, Finland.13,14

An economic crisis is the state of affairs provoked by a sudden and severe economic recession. Most recessions in history have been mild. An economic recession is characterized by rising unemployment and falling gross domestic product. In contrast with the scant suicide studies targeting economic crisis, an extensive literature exists on the association between suicide and unemployment. The study of the association between suicide and unemployment can be traced back to Durkheim,15 who stated that unemployment weakens a person's social integration and increases suicide risk.

Modern theories explaining the association between suicide and unemployment include the vulnerability model, the indirect causative model, and the noncausal link model.16,17 The vulnerability model suggests that unemployment may result in limited access to supportive resources, thereby increasing the impact of stressful events and then suicide risk. The indirect causative model indicates that unemployment may bring about relationship difficulties or financial problems that may lead to events precipitating suicide. The noncausal link model postulates that a third factor may increase the risk of both suicide and unemployment, resulting in a noncausal link between suicide and unemployment.

On the empirical side, positive, negative, and no associations between suicide and unemployment have all been found in the literature. For example, rising unemployment rates have been associated with increases in suicide rates in the United States,18–22 Japan,23 Italy,24 and many European Union countries,25 and with increases in male suicide rates in Australia26,27 and Spain.28 However, the association between suicide and unemployment was nonexistent in Scotland,29 significantly negative in the United Kingdom30 and Germany,31 unclear in France,32 and spurious in Ireland.33

Business cycles, consisting of economic expansions and recessions, are normally measured by changes in real gross domestic product, real income, employment, industrial production, and wholesale and retail sales.34 In our study we comprehensively examined the impact of business cycles on overall and age-specific suicide rates in the United States from 1928 to 2007. McKeown et al.35 conducted a noteworthy age-specific suicide study that examined the trends and the age, cohort, and period effects (1970–2002) of the suicide rates of 4 age groups. However, our study is the first to our knowledge to examine the relationship between business cycles and age-specific suicide rates. Our study design has 2 unique characteristics: first, it examines changes in the overall and age-specific suicide rates associated with business cycles, spanning the longest comparable time period (80 years) and including the largest number of age groups (8 distinct groups); second, it tests the associations between business cycles and suicide rates by using and extending the nonparametric method of Cook and Zarkin.36

METHODS

We collected suicide and economic data for the period 1928 to 2007. The age groups for calculating age-specific suicide rates were 5 to 14 years, 15 to 24 years, 25 to 34 years, 35 to 44 years, 45 to 54 years, 55 to 64 years, 65 to 74 years, and 75 years and older. For the period 1979 to 2006, we extracted suicide death numbers in total and by age groups from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention WONDER compressed mortality database.37,38 We took 2007 data from the newly released National Vital Statistical Reports.1 For the period 1928 to 1978, we collected data from the bound and historical volumes of the Vital Statistics of the United States.39

By 1933, all 48 existing states had been included in the federally defined group of death-registration states, and Alaska and Hawaii were included as soon as they gained statehood (1959 and 1960, respectively). However, the vital statistics of Alaska and Hawaii were available for earlier years because they had been included in the death-registration area as territories (Alaska since 1950 and Hawaii since 1917). Thus, the suicide data of all 50 current states became available starting in 1950. To conduct a comparable national-level suicide study across years in which the number of states changed, we needed to examine the results before and after the addition of new states. We found that the crude overall suicide rate (per 100 000) of the 48 states plus Alaska and Hawaii in 1950 was 11.3; that of the 48 states was also 11.3. This finding is consistent with the findings in Vital Statistics 1959 (page 1–1) and 1960 (page 1–1).39 Therefore, the comparison of national-level suicide rates is not substantially affected by the inclusion of Alaska and Hawaii.

To stretch the comparison back to 1928 was more challenging because of changes in the number of death-registration states from 1928 to 1933 (Supplementary Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Oklahoma was admitted and Georgia was readmitted to the death-registration states in 1928, Nevada and New Mexico were admitted in 1929, South Dakota was readmitted in 1930, and Texas was admitted in 1933. So there were 44 states in the death-registration states in 1928, 46 in 1929, 47 from 1930 to 1932, and 48 in 1933. In essence, we used the suicide rates of the death-registration states to approximate those of the United States from 1928 to 1932. Changes in the number of reporting states from 1928 to 1933 likely had a small effect on US suicide rates. For example, in 1933 the US suicide rate was 15.9 and would have been 16.1 absent Texas, a difference of 0.2. The admittance of Nevada and New Mexico in 1929 and the readmittance of South Dakota in 1930 resulted in almost no change in suicide rates because of these states’ small population sizes and suicide death numbers. Changes in the number of death-reporting states from 1928 to 1933 appear to have caused little difference in the US rates, and comparison of suicide rates over time starting in 1928 was feasible.

We collected and compiled total and subgroup population estimates by age groups from 1933 to 2007 from US Census Bureau data.40–44 For population estimates from 1980 to 2007, we chose the July 1 estimates of resident population plus armed forces overseas to preserve data consistency with previous years. We collected and compiled the population estimates of the death-registration states from 1928 to 1932 from Vital Statistics 1929 (p. 62) and 1940 (p. 22).39

The overall suicide rate in this study is the age-adjusted rate, which removes the effect of the population age distribution on the crude rate. The age-adjusted overall suicide rates from 1928 to 2007 were calculated on the basis of a fixed set of age-specific weights from the year 2000 standard population.45

Business-cycle data from 1928 to 2007, including the beginning and ending months of economic recessions and expansions, are available from the National Bureau of Economic Research.34 The time interval of the business-cycle charts in this study was a year rather than a month or a quarter because some monthly or quarterly suicide data were not available. In addition, we chose not to mark 2007 as a recession year for ease of illustration, although a recession began in December 2007.

After graphing and describing the overall and age-specific suicide rates in the business-cycle charts, we tested the associations between business cycles and suicide rates by using and extending the nonparametric method of Cook and Zarkin.36 Their study examined associations between business cycles and changes in crime rates by comparing 2 growth rates in crime: the average annual growth rate between each trough and the following peak, and the growth rate between the peak year and the subsequent year. If the former growth rate was less than the latter one, it was interpreted as evidence that recessions increased crime rates.

In our current study we modified their method in 2 ways. First, a business cycle is dated by months and often crosses years, which sometimes makes it hard to determine a trough or peak year in calculation; therefore, we replaced the trough year with the last year of contraction, and we replaced the peak year with the last year of expansion. We generally defined a year as being the last year of contraction if the contraction months outnumbered the expansion months, and we generally defined a year as being the last year of expansion if the expansion months outnumbered the contraction months. We also required the last year of contraction and the last year of expansion not to be the same year. When evaluating impacts of recessions on suicide rates, we compared the average annual growth rate in suicides between the last year of contraction and the last year of expansion in a business cycle with the growth rate in suicides between the last year of expansion and the subsequent year.

Our second modification was to examine whether expansions decreased suicide rates, in addition to studying whether recessions increased suicide rates. We did this by comparing the average annual growth rate between the last year of expansion and the last year of contraction with the growth rate between the last year of contraction and the subsequent year.

To complement the nonparametric tests of associations between business cycles and suicide rates, we calculated the coefficients of correlations between the national unemployment rate and suicide rates. We collected 1940 through 2007 unemployment data from Bureau of Labor Statistics Web sites,46,47 and we collected 1928 through 1939 data from the National Bureau of Economic Research.48 Data series of the unemployment rate and suicide rates were found nonstationary, so we calculated their correlation coefficients and the associated P values based on their first-differenced series, to correct for the potential bias.

RESULTS

We performed graphic analysis of changes in suicide rates in business cycles, conducted nonparametric tests of associations between business cycles and suicide rates, and measured correlations between the national unemployment rate and suicide rates.

Graphic Analysis of Changes in Suicide Rates in Business Cycles

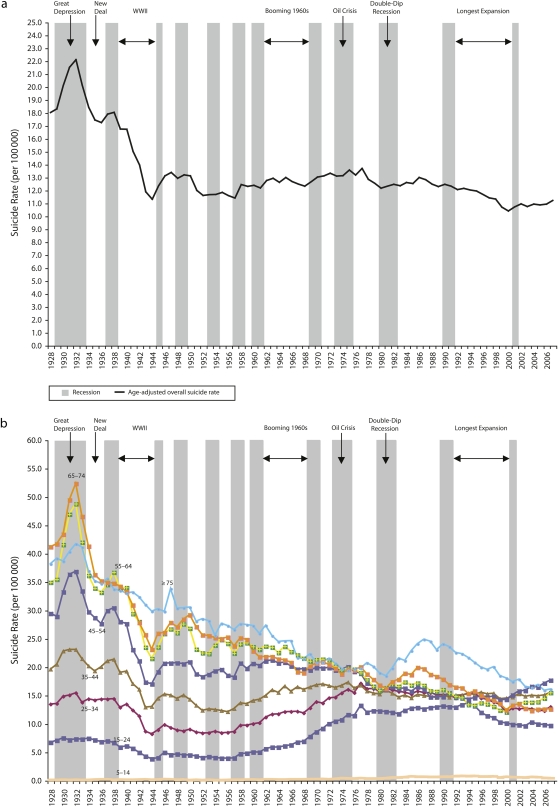

Overall and age-specific suicide rates are presented in Figure 1 (data for overall and age-specific suicide rates are presented in Supplementary Table B, available at http://www.ajph.org). The gray and white areas in Figure 1 represent economic recessions and expansions, respectively. The time interval in both parts of the figure is a year, so the widths of the gray and white areas only roughly approximate the durations of economic recessions and expansions, respectively.

FIGURE 1.

Suicide rates by (a) age-adjusted overall and (b) age group: United States, 1928–2007.

The overall suicide rate fluctuated from 10.4 to 22.1 over the 1928–2007 period. It peaked in 1932, the last full year of the Great Depression, and bottomed in 2000. The overall suicide rate decreased from 18.0 in 1928 to 11.2 in 2007. However, most of the decline occurred before 1945; after that it fluctuated until the mid-1950s, and then it gradually moved up until the late 1970s. The overall suicide rate resumed its downward trend from the mid-1980s to 2000, followed by a trend reversal in the new millennium.

Figure 1a shows that the overall suicide rate generally increased in recessions, especially in severe recessions that lasted longer than 1 year. The largest increase in the overall suicide rate occurred during the Great Depression (1929–1933), when it surged from 18.0 in 1928 to 22.1 (the all-time high) in 1932, the last full year of the Great Depression. This increase of 22.8% was the highest recorded for any 4-year interval during the study period. The overall suicide rate also rose during 3 other severe recessions: the end of the New Deal (1937–1938), the oil crisis (1973–1975), and the double-dip recession (1980–1982). Not only did the overall suicide rate generally rise during recessions; it also mostly fell during expansions. For example, the overall suicide rate posted the sharpest decrease during World War II (1939–1945) and the longest decrease during the longest expansion period (1991–2001); during both of these periods, the economy experienced fast growth and low unemployment. However, the overall suicide rate did not fall during the 1960s (i.e., 1961–1969), a notable phenomenon that will be explained by the different trends of age-specific suicide rates.

The age-specific suicide rates displayed more variations than did the overall suicide rate, and the trends of those age-specific suicide rates were largely different. As shown in Figure 1b, from 1928–2007, the suicide rates of the 2 elderly groups (65–74 years and 75 years and older) and the oldest middle-age group (55–64 years) experienced the most remarkable decline. The suicide rates of those groups declined in both pre- and postwar periods. The suicide rates of the other 2 middle-aged groups (45–54 years and 35–44 years) also declined from 1928–2007, which we attributed to the decrease during the war period more than offsetting the increase in the postwar period. In contrast with the declining suicide rates of the 2 elderly and 3 middle-age groups, the suicide rates of the 2 young groups (15–24 years and 25–34 years) increased or just marginally decreased from 1928–2007. The 2 young groups experienced a marked increase in suicide rates in the postwar period. The suicide rate of the youngest group (5–14 years) also increased from 1928–2007. However, because of its small magnitude, we do not include this increase in the subsequent discussion.

We noted that the suicide rate of the group aged 65–74 years, the highest of all age groups until 1936, declined the most from 1928 to 2007. That rate started at 41.2 in 1928 and dropped to 12.6 in 2007, peaking at 52.3 in 1932 and bottoming at 12.3 in 2004. By contrast, the suicide rate of the group aged 15–24 years increased from 6.7 in 1928 to 9.7 in 2007. That rate peaked at 13.7 in 1994 and bottomed at 3.8 in 1944, and it generally trended upward from the late 1950s to the mid-1990s. The suicide rate differential between the group aged 65–74 years and the group aged 15–24 years generally decreased until 1994, from 34.5 in 1928 to 1.6 in 1994.

All age groups experienced a substantial increase in their suicide rates during the Great Depression, and most groups (35–44 years, 45–54 years, 55–64 years, 65–74 years, and 75 years and older) set record-high suicide rates in 1932; but they reacted differently to many other recessions, including severe recessions such as the end of the New Deal and the oil crisis. Their reactions were different during expansions as well, most notably in the 1960s, when the suicide rates of the 3 oldest groups (75 years and older, 65–74 years, and 55–64 years) declined moderately, and those of the 3 youngest groups (15–24 years, 25–34 years, and 35–44 years) rose noticeably.

Nonparametric Tests of Associations Between Business Cycles and Suicide Rates

Table 1 shows the results of tests examining whether the overall and age-specific suicide rates rose relatively during each of the 13 recessions from 1928 to 2007. The trough and peak months of business cycles and the last years of contraction and expansion used in calculation are included. To save table space, we provided the average annual growth rate between the last year of contraction and the last year of expansion and the growth rate between the last year of expansion and the subsequent year only for the overall suicide rate.

TABLE 1.

Changes in Suicide Rates During Economic Recessions: United States, 1928–2007

| Age-Adjusted Overall Suicide Rate | Relatively Rise in Suicide Rate During Recession | ||||||||||||

| Trough | Peak | Last Years of Contraction Used in Calculation | Last Years of Expansion Used in Calculation | Average Annual Growth Rate Between Last Years of Contraction and Expansion, % | Growth Rate Between Last Years of Expansion and Next Years, % | Age-Adjusted Overall Suicide Rate | Age 15–24 Years | Age 25–34 Years | Age35–44 Years | Age 45–54 Years | Age 55–64 Years | Age 65–74 Years | Age ≥75 Years |

| Nov 27 | Aug 29 | 1927 | 1929 | 1.9 | 9.9 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Mar 33 | May 37 | 1932 | 1936 | −6.0 | 3.8 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Jun 38 | Feb 45 | 1938 | 1944 | −7.5 | 9.1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Oct 45 | Nov 48 | 1945 | 1948 | 1.6 | 2.0 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Oct 49 | Jul 53 | 1949 | 1953 | −3.0 | 0.1 | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| May 54 | Aug 57 | 1954 | 1957 | −0.8 | 9.2 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Apr 58 | Apr 60 | 1958 | 1959 | −1.2 | 0.7 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Feb 61 | Dec 69 | 1960 | 1969 | 0.3 | 2.8 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Nov 70 | Nov 73 | 1970 | 1973 | 0.2 | 0.3 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Mar 75 | Jan 80 | 1974 | 1979 | −0.9 | −3.0 | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Jul 80 | Jul 81 | 1980 | 1981 | 1.4 | 1.1 | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Nov 82 | Jul 90 | 1982 | 1990 | 0.0 | −1.1 | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Mar 91 | Mar 01 | 1991 | 2000 | −1.9 | 3.0 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Nov 01 | Dec 07 | 2001 | 2007 | 0.8 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Note. NA = not available.

As shown in Table 1, the overall suicide rate rose relatively in 11 of 13 recessions, suggesting the countercyclical nature of the overall suicide rate. Notably, we adjusted the relative overall suicide rate change associated with the July 1980–July 1981 expansion and the subsequent contraction to a rise. This adjustment was based on the fact that in the double-dip recession that occurred between January 1980 and November 1982, the overall suicide rate increased successively in 1981 and 1982. Table 1 also confirms that the suicide rates of different age groups responded differently to recessions. The suicide rates of 2 middle-aged groups (35–44 years and 45–54 years) rose relatively 10 and 11 times, respectively, whereas those of the youngest and oldest groups (15–24 years and 75 years and older) rose only 7 and 5 times, respectively.

Table 2 looks at the other side of the story—whether suicide rates fell relatively during each of the 13 expansions from 1928 to 2007. The overall suicide rate fell relatively in 10 of 13 expansions, which further suggests the overall suicide rate's countercyclical nature. The suicide rate of the group aged 45–54 years fell relatively 10 times, the most times among all age groups, followed by the suicide rates of the groups aged 25–34 years, 35–44 years, and 55–64 years, each falling 9 times. The suicide rates of the youngest and oldest groups (15–24 years and 75 years and older) again displayed little countercyclical sign, falling 7 and 5 times, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Changes in the Suicide Rates During Economic Expansions: United States, 1928–2007

| Age-Adjusted Overall Suicide Rate | Relatively Falling Suicide Rate During Expansion? | ||||||||||||

| Peak | Trough | Last Years of Expansion Used in Calculation | Last Years of Contraction Used in Calculation | Average Annual Growth Rate Between. Last Years of Expansion and Contraction, % | Growth Rate Between Last Years of Contraction and Next Years, % | Age-Adjusted Overall Suicide Rate | Age 15–24 Years | Age 25–34 Years | Age 35–44 Years | Age 45–54 Years | Age 55–64 Years | Age 65–74 Years | Age ≥75 Years |

| Aug 29 | Mar 33 | 1929 | 1932 | 6.5 | −8.9 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| May 37 | Jun 38 | 1936 | 1938 | 2.3 | −7.2 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Feb 45 | Oct 45 | 1944 | 1945 | 9.1 | 6.4 | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Nov 48 | Oct 49 | 1948 | 1949 | 2.0 | −0.6 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Jul 53 | May 54 | 1953 | 1954 | 0.1 | 1.4 | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Aug 57 | Apr 58 | 1957 | 1958 | 9.2 | −1.2 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Apr 60 | Feb 61 | 1959 | 1960 | 0.7 | −1.6 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Dec 69 | Nov 70 | 1969 | 1970 | 2.8 | 0.7 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Nov 73 | Mar 75 | 1973 | 1974 | 0.3 | 3.2 | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Jan 80 | Jul 80 | 1979 | 1980 | −3.0 | 1.4 | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Jul 81 | Nov 82 | 1981 | 1982 | 1.1 | −1.0 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Jul 90 | Mar 91 | 1990 | 1991 | −1.1 | −2.2 | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Mar 01 | Nov 01 | 2000 | 2001 | 3.0 | 2.2 | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Dec 07 | NA | 2007 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Note. NA = not available.

On the basis of the results shown in Tables 1 and 2, we used the 2-tailed χ2 test to examine associations between business cycles and suicide rates. As shown in Table 3, the overall suicide rate and the suicide rate of the group aged 45–54 years were associated with business cycles at the significance level of 1%; the suicide rates of the groups aged 25–34 years, 35–44 years, and 55–64 years were associated with business cycles at the significance level of 5%; and the suicide rates of the groups aged 15–24 years, 65–74 years, and 75 years and older were associated with business cycles at nonsignificant levels. To sumarize, the overall suicide rate was significantly countercyclical; the suicide rates of the groups aged 25–34 years, 35–44 years, 45–54 years, and 55–64 years were significantly countercyclical; and the suicide rates of the groups aged 15–24 years, 65–74 years, and 75 years and older were not significantly countercyclical.

TABLE 3.

Test of Associations Between Business Cycles and Suicide Rates: United States, 1928–2007

| Age-Specific Suicide Rates | ||||||||

| Age-Adjusted Overall Suicide Rate | 15–24 Years | 25–34 Years | 35–44 Years | 45–54 Years | 55–64 Years | 65–74 Years | ≥75 Years | |

| Recessions | ||||||||

| No. of times suicide rate rose | 11 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 9 | 5 |

| No. of times suicide rate fell | 2 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| Expansions | ||||||||

| No. of times suicide rate rose | 3 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 8 |

| No. of times suicide rate fell | 10 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 5 |

| χ2 | 9.9048 | 0.1538 | 5.5714 | 5.5714 | 9.9048 | 3.8462 | 2.4762 | 1.3846 |

| P | .002 | .695 | .018 | .018 | .002 | .05 | .116 | .239 |

The growth rates for the suicide rates associated with the first business cycle studied (expansion from November 1927 to August 1929 and contraction from August 1929 to March 1933) were approximately calculated because the number of death-registration states changed during this period. However, this approximation should not materially alter the previous findings, because the gaps between the rates’ average annual growth and their growth in the following year were very large. For example, Table 1 shows that the overall suicide rate grew at an annual average of 1.9% from 1927 to 1929, but it spiked 9.9% in 1930. Table 2 shows that the overall suicide rate rose 6.5% on average annually from 1929 to 1932, but it plunged 8.9% in 1933.

Correlations Between the National Unemployment Rate and Suicide Rates

The overall suicide rate and the suicide rates of the groups aged 25–34 years, 35–44 years, 45–54 years, 55–64 years, and 65–74 years were positively, significantly correlated with the national unemployment rate, with correlation coefficients of 0.58525 (P < .001), 0.33377 (P = .003), 0.40754 (P < .001), 0.60984 (P < .001), 0.61876 (P < .001), and 0.56896 (P < .001), respectively. However, correlations of the suicide rates of the youngest and oldest groups (15–24 years and 75 years and older) with the national unemployment rate were insignificant (0.1773; P = .118 and 0.13476; P = .236, respectively). The correlation results are concordant with all nonparametric test results except for the group aged 65–74 years. Increases in unemployment are not identical to recessions, but this test allows us to examine the robustness of our nonparametric results.

DISCUSSION

If business cycles do affect suicide rates, policymakers and public health workers must increase suicide-prevention measures when adverse economic conditions emerge. Our findings suggest the importance of population-level suicide-prevention strategies, particularly during recessions. For example, during recessions importance must be placed on providing social support and counseling services to those who lose jobs or homes; promoting individual, family, and community connectedness49; and providing adequate resources to crisis call centers50–52 and other community services.

We must also understand which age groups are most at risk during recessions, so that desired outcomes are achieved more effectively and efficiently. We found that people in prime working ages (25–64 years) were more vulnerable to recession than were others. This may be partly explained by the fact that many of those people were breadwinners in their homes, and their jobs supported mortgage payments, health insurance, childrens’ education, and other expenses. Therefore, job loss may cause more hardships to those people than to others. In addition, many people older than 65 years are no longer in the labor force, and many adolescents and college students have not yet entered the labor market, so they are less vulnerable to recession.

The different responses of age-specific suicide rates to economic expansions and contractions are worth exploring. Strikingly, the 2 young groups and the youngest middle-age group (35–44 years) experienced an increase in suicide rates during the booming 1960s, whereas the 2 elderly groups posted a decrease in suicide rates during a severe recession in the mid-1970s. These noteworthy changes may imply that for the young groups, some risk factors for suicide outweighed the benefit of economic expansion; for the elderly groups, some protective factors for suicide may have more than offset the risk of a severe recession. For example, the social unrest and tumult of the 1960s may have added to young people's mental stress and therefore contributed to their continuously rising suicide rates. For the elderly groups, the rapid increase in Social Security benefits in the late 1960s may have provided a safety net in hard times.53

Research has shown that suicidal behavior results from an interaction of factors. The finding that business cycles are associated with suicide among certain groups may indicate that economic hardships are a precipitating factor for some individuals who likely have other existing risk factors. The multifaceted nature of suicide indicates the need to develop prevention efforts that use multiple settings where vulnerable individuals may be found. For example, patterns of suicide among people of prime working ages appeared to be the most strongly associated with business cycles, so possible settings for prevention could include the workplace and employee assistance programs because some people may be experiencing job plateauing or job shifts.54–56

A limitation of this study is inherent in its nonparametric method, which treats each recession the same and does not differentiate recessions according to their duration or severity. This treatment, although convenient for analysis, may mask different impacts of recessions on suicides. Another limitation is that this study focused only on business cycles and therefore ignored other social, cultural, and medical factors that may explain some of the associations observed or that may have independent associations with suicide rates. Future research that examines the associations between economic factors and suicide may overcome these limitations by using multiple regression analyses.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Thomas Simon, Linda Anne Valle, and Linda Dahlberg for their helpful discussions of an early version of the article. The authors also thank two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments on the article.

Human Participant Protection

No institutional review board approval was required because no human research participants were involved in this study.

References

- 1.Xu JQ, Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: final data for 2007. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2010; 58(19):1–136 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stack S. Suicide: a 15-year review of the sociological literature. Part I: culture and economic factors. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2000;30(2):145–162 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Massachusetts woman commits suicide before home foreclosure. Fox News Web site. July 23, 2008. Available at: http://www.foxnews.com/printer_friendly_story/0, 3566, 389822,00.html. Accessed May 19, 2010.

- 4.Adams JU. Is the economic crisis leading to more suicides? Los Angeles Times. October 27, 2008. Available at: http://www.latimes.com/features/health/la-he-closer27-2008oct27,0,445227,print.story. Accessed October 29, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelly K. His job at Bear gone, Mr. Fox chose suicide. Wall Street Journal. November 6, 2008. Available at: http://online.wsj.com/article/SB122593803133403929.html. Accessed November 6, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson S, Broughton A, Vercammen P. With no job and 5 kids, "better to end our lives," man wrote. CNN Web site. January 29, 2009. Available at: http://www.cnn.com/2009/CRIME/01/29/family.dead.california/index.html?iref=mpstoryview. Accessed January 29, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tapia Granados JA, Diez Roux AV. Life and death during the Great Depression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(41):17290–17295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim H, Song YJ, Yi JJ, Chung WJ, Nam CM. Changes in mortality after the recent economic crisis in South Korea. Ann Epidemiol. 2004;14(6):442–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watts J. Suicide rate rises as South Korea's economy falters. Lancet. 1998;352(9137):1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang SS, Gunnell D, Sterne JA, Lu TH, Cheng AT. Was the economic crisis 1997–1998 responsible for rising suicide rates in East/Southeast Asia? A time-trend analysis for Japan, Hong Kong, South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and Thailand. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(7):1322–1331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stuckler D, Basu S, Suhrcke M, Coutts A, McKee M. The public health effect of economic crises and alternative policy responses in Europe: an empirical analysis. Lancet. 2009;374(9686):315–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.La Harpe R, Dozio A. Economic crisis and suicide in Geneva: 1991–1995. Arch Kriminol. 1998;202(3–4):69–74 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ostamo A, Lönnqvist J. Attempted suicide rates and trends during a period of severe economic recession in Helsinki, 1989–1997. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2001;36(7):354–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ostamo A, Lahelma E, Lönnqvist J. Transitions of employment status among suicide attempters during a severe economic recession. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52(11):1741–1750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Durkheim E. Suicide: A Study in Sociology. New York, NY: Free Press; 1897 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones SC, Forster DP, Hassanyeh F. The role of unemployment in parasuicide. Psychol Med. 1991;21:169–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beautrais AL, Joyce PR, Mulder RT. Unemployment and serious suicide attempts. Psychol Med. 1998;28:209–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang B. The economy and suicide: a time-series study of the USA. Am J Econ Sociol. 1992;51(1):87–99 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang B, Lester D, Yang CH. Sociological and economic theories of suicide: a comparison of the USA and Taiwan. Soc Sci Med. 1992;34(3):333–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chuang HL, Huang WC. A reexamination of “sociological and economic theories of suicide: a comparison of the USA and Taiwan.” Soc Sci Med. 1996;43(3):421–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruhm C. Are recessions good for your health? Q J Econ. 2000;115(2):617–650 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tapia Granados JA. Increasing mortality during the expansions of the US economy, 1900–1996. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34(6):1194–1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Granados JA. Macroeconomic fluctuations and mortality in postwar Japan. Demography. 2008;45(2):323–343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Preti A, Miotto P. Suicide and unemployment in Italy, 1982–1994. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53(11):694–701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Economou A, Nikolaou A, Theodossiou I. Are recessions harmful to health after all? Evidence from the European Union. J Econ Stud. 2008;35(5):368–384 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morrell S, Taylor R, Quine S, Kerr C. Suicide and unemployment in Australia 1907–1990. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36(6):749–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berk M, Dodd S, Henry M. The effect of macroeconomic variables on suicide. Psychol Med. 2006;36(2):181–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tapia Granados JA. Recessions and mortality in Spain, 1980–1997. Eur J Popul. 2005;21(4):393–422 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crombie IK. Trends in suicide and unemployment in Scotland, 1976–86. BMJ. 1989;298(6676):782–784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boor M. Relationships between unemployment rates and suicide rates in eight countries, 1962–1976. Psychol Rep. 1980;47:1095–1101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neumayer E. Recessions lower (some) mortality rates: evidence from Germany. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(6):1037–1047 [erratum in Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(9):1993] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buchmueller T, Grignon M, Jusot F. Unemployment and mortality in France, 1982–2002. Available at: http://www.chepa.org/Portals/0/pdf/CHEPA%20WP%2007-04.pdf. Centre for Health Economics and Policy Analysis working paper 07-04. Accessed August 4, 2010

- 33.Lucey S, Corcoran P, Keeley HS, Brophy J, Arensman E, Perry IJ. Socioeconomic change and suicide: a time-series study from the Republic of Ireland. Crisis. 2005;26(2):90–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Bureau of Economic Research US business cycle expansions and contractions. Available at: http://www.nber.org/cycles/cyclesmain.html. Accessed March 11, 2009

- 35.McKeown RE, Cuffe SP, Schulz RM. US suicide rates by age group, 1970–2002: an examination of recent trends. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(10):1744–1751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cook PJ, Zarkin GA. Crime and the business cycle. J Legal Stud. 1985;14(1):115–128 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC WONDER online database. Compiled from Compressed Mortality File 1999–2006, series 20 no. 2L, 2009. Available at: http://wonder.cdc.gov/cmf-icd10.html. Accessed November 25, 2009.

- 38.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC WONDER online database. Compiled from Compressed Mortality File CMF 1968–1988, series 20, no. 2A, 2000, and CMF 1989–1998, series 20, no. 2E, 2003. Available at: http://wonder.cdc.gov/cmf-icd9.html. Accessed November 25, 2009.

- 39.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Vital statistics of the United States. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/vsus.htm. Accessed April 2, 2010

- 40.US Census Bureau. Population estimates; national estimates; national estimates by age, sex, race: 1900–1979 (PE-11). Available at: http://www.census.gov/popest/archives/pre-1980/PE-11.html. Accessed March 27, 2009.

- 41.US Census Bureau Population estimates; quarterly population estimates; national estimates; quarterly population estimates, 1980 to 1990. Available at: http://www.census.gov/popest/archives/1980s/80s_nat_detail.html. Accessed April 2, 2009

- 42.US Census Bureau. Population estimates; monthly population estimates; monthly population estimates, 1990 to 2000. Available at: http://www.census.gov/popest/archives/1990s/nat_detail.html. Accessed April 2, 2009.

- 43.US Census Bureau. National estimates; monthly population estimates, 2000 to 2006. Available at: http://www.census.gov/popest/national/asrh/2006_nat_detail.html. Accessed April 3, 2009.

- 44.US Census Bureau. Population estimates; 2007 monthly national population estimates. Available at: http://www.census.gov/popest/national/asrh/2007-nat-detail.html. Accessed June 15, 2009.

- 45.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. CDC WONDER online database. Compressed Mortality File 1979–1998 and 1999–2007. Available at: http://wonder.cdc.gov/wonder/help/cmf.html. Accessed March 20, 2009

- 46.Bureau of Labor Statistics. Labor force statistics from the Current Population Survey. Where can I find the unemployment rate for previous years? Available at: http://www.bls.gov/cps/prev_yrs.htm. Accessed November 12, 2009.

- 47.Bureau of Labor Statistics. Household data annual averages: 1. Employment status of the civilian noninstitutional population, 1940 to date. Available at: http://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat1.pdf. Accessed November 12, 2009.

- 48.Lebergott S. Annual estimates of unemployment in the United States, 1900–1954. National Bureau of Economic Research Web site. Available at: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c2644. Accessed November 12, 2009

- 49.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Strategic direction for the prevention of suicidal behavior: promoting individual, family, and community connectedness to prevent suicidal behavior. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/Suicide_Strategic_Direction_Full_Version-a.pdf. Accessed May 20, 2010

- 50.Dwyer D. National suicide hotline inundated by economically distressed. ABC News Web site. August 7, 2009. Available at: http://abcnews.go.com/print?id=8267806. Accessed August 13, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kalafat J, Gould MS, Munfakh JL, Kleinman M. An evaluation of crisis hotline outcomes. Part 1: nonsuicidal crisis callers. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2007;37(3):322–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gould MS, Kalafat J, Harrismunfakh JL, Kleinman M. An evaluation of crisis hotline outcomes. Part 2: suicidal callers. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2007;37(3):338–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cutler DM, Meara E. Changes in the age distribution of mortality over the 20th century. NBER working paper 8556. Available at: http://www.nber.org/papers/w8556.pdf. Published October 2001. Accessed August 31, 2009

- 54.Paul R, Jones E. Suicide prevention: leveraging the workplace. EAP Digest. 2009;Winter:18–21 [Google Scholar]

- 55.World Health Organization. Preventing suicide: a resource for work. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2006/9241594381_eng.pdf. Published 2006. Accessed May 24, 2010.

- 56.Knox KL, Caine ED. Establishing priorities for reducing suicide and its antecedents in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(11):1898–1903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]