Abstract

Objectives. We examined the efficacy of a peer-driven intervention to increase rates of screening for AIDS clinical trials among African Americans and Hispanics living with HIV/AIDS.

Methods. We used a randomized controlled trial design to examine the efficacy of peer-driven intervention (6 hours of structured sessions and the opportunity to educate 3 peers) compared with a time-matched control intervention. Participants were recruited using respondent-driven sampling (n = 342; 43.9% female; 64.9% African American, 26.6% Hispanic). Most participants (93.3%) completed intervention sessions and 64.9% recruited or educated peers. Baseline and post-baseline interviews (94.4% completed) were computer-assisted. A mixed model was used to examine intervention effects on screening.

Results. Screening was much more likely in the peer-driven intervention than in the control arm (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 55.0; z = 5.49, P < .001); about half of the participants in the intervention arm (46.0%) were screened compared with 1.6% of controls. The experience of recruiting and educating each peer also increased screening odds among those who were themselves recruited and educated by peers (AOR = 1.4; z = 2.06, P < .05).

Conclusions. Peer-driven intervention was highly efficacious in increasing AIDS clinical trial screening rates among African Americans and Hispanics living with HIV/AIDS.

African Americans and Hispanics in the United States are over-represented in HIV/AIDS cases,1 yet individuals from these racial/ethnic groups experience disproportionately higher rates of morbidity and mortality compared with Whites.2 For example, from 1996 to 2006 African Americans with HIV/AIDS were 6 times more likely to be hospitalized for HIV/AIDS-related causes than were Whites.3,4 Further, in the period from 1987 to 2005, African American HIV mortality was 5 times higher than was that of Whites.5,6 Moreover, these racial/ethnic disparities are increasing.1,7

AIDS clinical trials test the safety and efficacy of potential treatments for HIV/AIDS and associated complications. As such, clinical trials are critical to the development of new medication and treatment regimens. By participating in clinical trials, persons living with HIV/AIDS can access new treatments and may also receive a level of care and support not otherwise available to them.8 However, people of color are under-represented in such trials.8,9 Hispanics historically have been modestly under-represented in trials,8 and African Americans compose approximately 48% of all people living with HIV/AIDS but only 30% of participants in AIDS clinical trials.5,10 The limited enrollment of people of color in AIDS clinical trials raises questions about the applicability of research findings to the populations most affected by HIV/AIDS. Indeed, the Underrepresented Populations Committee of the Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases has made substantial progress in exposing and reducing disparities in AIDS clinical trials.11,12 Yet impediments to trials for these groups are persistent.

Barriers to clinical trials are multifaceted and complex for people of color living with HIV/AIDS. Knowledge of AIDS clinical trials tends to be poor.13 Attitudes toward trials are complex: People of color exhibit a high level of willingness to participate in the trials, despite also experiencing fear and distrust of clinical research.13–15 Conspiracy theories about the cause of AIDS and skepticism about HIV treatments persist, especially in African American communities, and these beliefs foster social norms that discourage participation in medical research.16,17 Moreover, people of color are infrequently referred to AIDS clinical trials by health care providers.18 Structural factors also may impede access. For example, clinical trials are often conducted in locations and settings that differ from the venues at which people of color living with HIV/AIDS receive health care.8,19 Women with HIV/AIDS face additional barriers, including child care and family responsibilities.20,21

People enter AIDS clinical trials through a screening process to determine eligibility, and screening is therefore a critical gateway to accessing clinical trials.22 Screening is a minimal-risk exchange that may also yield indirect benefits to those who participate, such as enhanced knowledge and reduced fear and distrust of AIDS clinical trials. Despite these potential direct and indirect benefits of screening however, people of color present for screening at very low rates.22 Furthermore, few behavioral interventions have been developed to increase rates of screening among this population.23 This study, the ACT2 Project, which follows our pilot ACT1 Project, is the first randomized controlled trial of a behavioral intervention to reduce barriers to screening for AIDS clinical trials for people of color living with HIV/AIDS. The intervention was designed to reduce barriers to AIDS clinical trials at multiple levels, including those affecting individuals and their social networks, and the social and structural impediments associated with health care providers and clinical trial settings, as previously described.

We designed a randomized controlled trial to address whether the peer-driven ACT2 intervention would be equally, more, or less efficacious in increasing clinical trial screening rates among people of color living with HIV/AIDS compared with a time- and attention-matched control intervention. Participants in the control arm also received treatment as usual, namely, referrals to AIDS clinical trial screening. A second objective was to describe the sociodemographic, health, and intervention-related correlates of screening.

Peer-driven intervention is an effective, culturally appropriate, and low-cost intervention methodology that taps into 6 critical elements of behavior change: knowledge, skill building, motivation, peer influence, social norms, and repetition.24–26 In this type of intervention, individuals participate in facilitated intervention activities targeting critical mediators of behavior change (e.g., knowledge, self efficacy, motivation), and then independently educate peers on selected core messages, for which compensation is provided. It is hypothesized that through peer education an individual's own commitment to engage in the targeted outcome behavior is strengthened because the act of educating peers is a public affirmation of the outcome behavior. Further, peer education is a means of repeating the intervention's core messages and thus may promote the educator's understanding and internalization of these messages, and at the same time potentially influence the peer's attitudes and knowledge.26 Ideally, through successive waves of recruitment and peer education, network social norms are altered.27 Peer-driven intervention has been used successfully with people of color living with HIV/AIDS to increase medication adherence28 and reduce HIV-related sexual and drug use risk behavior.26,29

The peer-driven intervention in our study was tailored to address 3 streams of influence on AIDS clinical trial screening behavior30: the individual/intrapersonal (e.g., knowledge and skills that contribute to self efficacy), attitudinal/cultural (e.g., attitudes such as willingness, altruism, fear, and distrust rooted in the cultural context), and social/structural factors (e.g., social normative beliefs and interactions, health care providers, and structural barriers such as difficulties accessing the trials system). The intervention's mechanisms of action were grounded in the Theory of Normative Regulation,31 which posits that the behaviors of individuals are amplified through their social groups, as well as Motivational Interviewing, a method for enhancing intrinsic motivation to change by exploring and resolving ambivalence,32,33 and social-cognitive theory, which emphasizes individual and social-contextual influences on behavior.37,38

METHODS

Because peer-driven intervention includes interactions with a small number of peers, it can be integrated with the respondent-driven sampling (RDS) method, a type of snowball sampling in which individuals are trained to recruit their peers into research.30 RDS is an efficient sampling method for populations that are linked by characteristics that encourage the formation of social networks made up of those with this same characteristic, such as HIV infection.36–38

A total of 342 people of color living with HIV/AIDS were recruited through RDS31 in New York, New York, between June 2008 and June 2009. To generate an RDS sample, a small number of initial participants (seeds) are selected from the target population. Each seed recruits a small number of peers, and these peers then recruit their own peers. For our study, recruitment began with 49 initial seeds nominated by staff at 2 community-based organizations serving people living with HIV/AIDS. Initial seeds were active clients at the organizations, aged 18 years or older, HIV-infected (confirmed by medical documentation), African American or Hispanic, willing to recruit HIV-infected peers, able to conduct research activities in English, and not currently enrolled in an AIDS clinical trial. Participants received training on how to recruit peers during intervention sessions and were then given 3 coded referral coupons to give to peers, 1 of which was allotted for a female recruit to insure that approximately 40% of the sample was female. The peer education training included the importance of maintaining the confidentiality of both parties and how to recruit without coercion. Compensation was provided to the recruiter for each peer recruited. Racial/ethnic background was not an inclusion criterion for peers, nor were they required to be active clients of the community-based organizations. The 49 initial seeds recruited 293 peers over 5 recruitment waves.

Design

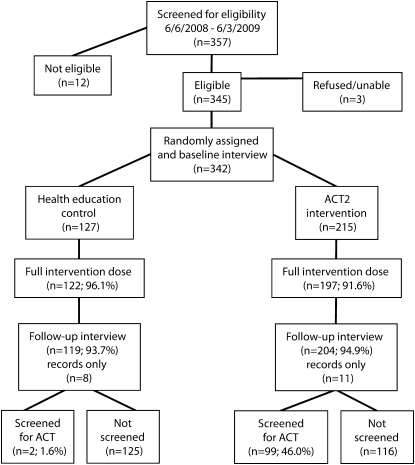

Initial seeds were randomly assigned to the intervention or control arm at a 2-to-1 ratio at the time of the baseline interview (Figure 1). Participants in the intervention arm were trained to educate their peers on core messages about AIDS clinical trials during the recruitment process (See Appendix 1, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Participants in the control arm recruited but did not educate peers. Thus, in contrast to typical intervention designs, intervention activities started at the time of recruitment for those in the peer-driven intervention arm of the study. As a result, peers found eligible for the study could not be randomized at the individual level and were therefore assigned to the same arm as the recruiter. The design is the equivalent of a cluster randomized controlled trial.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of the ACT2 Project, New York, NY, 2008–2009.

Note. ACT = AIDS clinical trial.

Procedures

Initial seeds and peers presented with a coded recruitment coupon, provided written informed consent, and participated in a 20-minute structured screening interview to determine study eligibility. The screening interview included questions about the peer recruitment/education experience and relationship between the recruiter and recruit. Participants received $15 compensation for the screening interview. Those found to be eligible then provided written informed consent for remaining project activities, including assessments (structured baseline and a follow-up assessment 16 weeks later, each lasting 1–1.5 hours) and intervention activities. Participants received $25 compensation for each assessment and intervention session. Assessments were conducted in a private location at a study field site and intervention activities were conducted at the field site and hospital site.

Assessment

Trained staff administered the interviews using laptop computers, which consisted of computer-assisted personal interview and audio, computer-assisted self-interviewing segments.39,40 Health indices, including date of first HIV, AIDS, and HCV diagnoses; CD4+ and viral load levels; and antiretroviral history, were assessed with the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study measure.41 (CD4+ T lymphoctyes are an essential subset of the cellular immune system, and CD4+ lymphoctye cell counts are key measures of HIV induced immune system damage and are central to monitoring antitretroviral treatment response.) A risk behavior assessment was used to evaluate substance use and injection drug use over the lifetime.42 We also assessed demographic and background characteristics such as gender, race/ethnicity, and age.

Intervention dose was the number of intervention sessions completed (maximum = 4) and peers educated/recruited (maximum = 3). The primary endpoint for the study was participation in screening for AIDS clinical trials to the point of determining eligibility (yes or no). To construct the outcome variable, participants were asked at the 16-week assessment, “Were you screened for an AIDS clinical trial since your last interview?” Then, all self-reports of screening (whether the participant reported being screened or not) were verified using a separate data source collected on those who presented for screening at the collaborating hospital site and other clinical trials sites as appropriate. For 11 participants who did not complete a 16-week assessment, screening was determined from records only.

The peer-driven and control interventions were facilitated by trained and supervised, master's-level clinicians. To insure fidelity to the intervention manuals, facilitators completed written quality assurance ratings after each session. These were reviewed by a supervisor. Intervention sessions were videotaped and 10% were selected at random for review. A clinical supervisor provided regular feedback to facilitators based on quality assurance ratings and review of the videotape.

Interventions

The peer-driven intervention was developed, pilot tested, and revised in previous research.22 The intervention included 6 hours of structured, facilitated sessions plus the opportunity to educate up to 3 peers about AIDS clinical trials. The intervention was manual-based and included interactive group exercises and videotaped components. The intervention curriculum is available from the first author; the following is a brief description of the sequence of intervention activities.

With the exception of initial seeds who started the recruitment chains, participants were educated by peers on core intervention messages at the time of recruitment. Peer education was intended to solidify the educator's commitment to the outcome behavior, provide the peer with information about the intervention's aims and content to generate motivation to explore the topic, and influence social norms.

Participants engaged in 3 small group sessions (5.5 hours total) with 6 to 9 other people living with HIV/AIDS. Sessions were designed to increase knowledge, self-efficacy, and behavioral skills; to build motivation for screening; and to influence peer norms.

Participants then had the opportunity to independently educate 3 peers on 10 core intervention messages. To boost motivation to conduct peer education thoroughly, recruiters received $15 compensation based on peers presenting to the study and a bonus of up to $10 based on peers' performance on a 10-item knowledge test ($1 for each item answered correctly by the peer). A total of 65.6% of participants educated/recruited an average of 1.95 peers each (SD = 0.80; minimum = 1; maximum = 3). Participants could decline to educate/recruit peers and continue in the study.

The peer education period was followed by a final intervention session lasting 30 minutes, held with participants individually at the AIDS clinical trials unit in the medical center where actual screening visits also took place. Locating the final session at the clinical trials unit was designed to enable participants to access and become more comfortable with the unfamiliar venue and personnel. The session also facilitated participants’ final decisions about whether they would choose to be screened for AIDS clinical trials. Participants who wished to be screened were then provided with contact information for the screener at the clinical trials unit. Consistent with typical clinical trials practices, no compensation was provided for screening. Thus, the screening process was congruent with real-world practices in which patients are referred to screening but must take initiative to attend, no compensation is provided, and screening is conducted at a location separate from the HIV care setting (which is common). Total possible compensation for intervention arm participants was $250.

All participants who indicated they wished to be screened received 1 to 3 short telephone contacts from staff to resolve potential barriers to screening such as transportation, directions, or assistance obtaining records from or interacting with primary care providers. Telephone contacts were considered a necessary component of the intervention but were not analyzed quantitatively because of their short duration, variable content, and the fact that all screened participants received such contacts.

Participants in the control arm received a time- and attention-matched health education intervention (3 sessions, 6 hours of structured activities). Using a support group model, the sessions included video and interactive components providing information tailored for HIV-infected adults on the management of health. Sessions covered topics such as medication adherence, nutrition, exercise, social support, and safer sexual behavior.43 Participants were trained to recruit (but not educate) up to 3 peers for the study. Participants received $15 for each peer referred to the study. Total possible compensation for control arm participants was $195.

Analysis

The focus of the analysis was the difference between participants in the peer-driven intervention arm and those in the control arm of the study in the probability of being screened for an AIDS clinical trial to the point of determining eligibility. Prior to this comparison, we examined the simple associations between study arm (intervention or control) and sociodemographic and health characteristics at baseline. Within the intervention arm, we also examined simple associations between sociodemographic and health characteristics at baseline and screening. (We limited associations with screening to the intervention arm because nearly all participants screened were in that arm). Any sociodemographic or health characteristic associated with either the intervention arm or the screening outcome in bivariate analyses was included as a covariate when comparing intervention arms on the probability of AIDS clinical trial screening in multivariate analyses.

To account for clustering of the 342 individual participants in 49 recruitment chains initiated by the 49 initial seeds, a logistic generalized linear mixed-model analysis with a random intercept44 was used to estimate the relationships between intervention arm and the outcome variable of screening for an AIDS clinical trial. The lme4 package45 of the freely available, open-source R program46 was used to fit the logistic generalized linear mixed model. In addition to the intervention arm variable, other variables were included in the logistic generalized linear mixed model if they were related to either intervention arm or the screening outcome within the intervention arm. The model was fit with a binomial distribution family, logit link function, and thirty quadrature points for evaluating the adaptive Gauss-Hermite approximation to the log-likelihood. Apart from increasing the number of quadrature points, these were the default settings for lme4.

RESULTS

Of the 49 initial seeds, 31 (63%) recruited 1 or more participants. Homophily coefficients indicate the degree to which individuals have a preference for connections to others with a shared characteristic and can range from −1 to +1. We calculated homophily coefficients for gender, age, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, antiretroviral history, CD4+ count (an indicator of immune system damage), viral load, recency of HIV diagnosis, AIDS diagnosis, injection drug use history, HCV diagnosis, prior AIDS clinical trial screening, and the screening outcome. Across all characteristics, homophily was modest, on average (mean = 0.06; SD = 0.17), and ranged from moderate heterophily (-0.45) for participants diagnosed with HIV within the past 9 years to moderate homophily (0.40) for participants diagnosed with HIV 10 or more years ago. Homophily also was moderate (0.31) for participants achieving the desired outcome of screening for an AIDS clinical trial. On the whole, patterns of recruitment suggest moderate preference for connections with members of a participant's own group, but also a substantial number of connections with people outside of a participant's own group.

Figure 1 provides an overview of eligibility, assignment to study arms, follow-up rates, and outcomes. Most of the individuals screened for the project were eligible and were enrolled (95.8%; 342/357). Of those enrolled, almost all (93.3%) participated in the full set of structured intervention activities, and there was no difference between study arms. Almost all participants (94.4%) completed the follow-up interview, and again there was no difference between study arms.

Sociodemographic and health characteristics in each intervention arm and the total sample are presented in Table 1. A total of 43.9% of the sample was female. Almost half the participants (47.7%) were between 41 and 50 years of age, almost all (91.5%) were people of color (64.9% African American, 26.6% Hispanic), and about two-thirds recruited or recruited and educated at least 1 peer (64.9%). The majority of the participants were on antiretroviral therapy (67.4%) and reported viral load levels as undetectable (67.6%). A third (33%) had tested positive for HCV. A total of 19.6% had been screened for AIDS clinical trials in the past.

TABLE 1.

Participant Sociodemographic and Health Characteristics at Baseline: ACT2 Project, New York, NY, 2008–2009

| Participant Characteristic | Control (n = 127) | Intervention (n = 215) | Total (n = 342) |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||

| Women | 42.5 | 44.7 | 43.9 |

| Aged 18—40 y | 13.4 | 10.7 | 11.7 |

| Aged 41—50 y | 46.5 | 48.4 | 47.7 |

| Aged ≥ 51 y | 40.2 | 40.9 | 40.6 |

| African Americana | 55.1 | 70.7 | 64.9 |

| Hispanica | 35.4 | 21.4 | 26.6 |

| Heterosexual | 68.5 | 72.6 | 71.1 |

| Intervention dose | |||

| Completed all sessions | 96.1 | 91.6 | 93.3 |

| Completed ≥ 1 session | 97.6 | 98.1 | 98.0 |

| Recruited or recruited/educated peers | 63.8 | 65.6 | 64.9 |

| Health characteristics | |||

| Current antiretroviral therapy | 63.8 | 69.6 | 67.4 |

| CD4 < 350 | 31.9 | 36.4 | 34.8 |

| Undetectable viral load | 69.7 | 66.3 | 67.6 |

| HIV diagnosis ≥ 10 y | 75.4 | 81.0 | 78.9 |

| AIDS diagnosis | 59.2 | 54.5 | 56.2 |

| Ever injected drugs | 31.5 | 29.8 | 30.4 |

| Ever had HCV | 34.6 | 32.1 | 33.0 |

| Prior AIDS clinical trial screeninga | 11.8 | 24.2 | 19.6 |

P < .05, χ2 test of association.

No differences were found between the intervention and control arm participants on the sociodemographic and health characteristics at baseline with 2 exceptions. First, participants assigned to the intervention arm were more likely to be African American and less likely to be Hispanic. This difference was the result of a slight imbalance in race/ethnicity among initial seed participants, a stronger preference for in-group recruitment among African Americans, and more successful recruitment by African Americans in that study arm. Second, those in the intervention arm were more likely to have been screened for an AIDS clinical trial in the past because more initial seeds in the intervention arm (28%) had prior screening than did initial seeds in the control arm (12%), and initial seeds with prior screening initiated more productive recruitment chains. We controlled for the effect of these between-group differences in the analysis of intervention effects.

Nearly half (46.0%) of all participants in the intervention arm of the study were screened; however, only 2 (1.6%) participants in the control arm were screened. Table 2 presents sociodemographic and health characteristics among participants in the intervention arm who did and did not undergo screening for an AIDS clinical trial. There were 3 statistically significant differences: (1) screened participants were less likely to be younger than were those not screened (6.1% vs 14.7%), (2) screened participants were more likely to have completed all intervention sessions than were those not screened (98.0% vs 86.2%), and (3) screened participants were more likely to have recruited and educated peers than were those not screened (71.7% vs 60.3%).

TABLE 2.

Sociodemographic and Health Characteristics of Study Intervention Arm Participants by Screening Outcome: ACT2 Project, New York, NY, 2008–2009

| Participant Characteristic | Not Screened (n = 116) | Screened (n = 99) |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||

| Women | 46.6 | 42.4 |

| Aged 18—40 ya | 14.7 | 6.1 |

| Aged 41—50 y | 50.0 | 46.5 |

| Aged ≥ 51 y | 35.3 | 47.5 |

| African American | 71.6 | 69.7 |

| Hispanic | 22.4 | 20.2 |

| Heterosexual | 69.8 | 75.8 |

| Intervention dose | ||

| Completed all sessionsa | 86.2 | 98.0 |

| Completed ≥ 1 session | 97.4 | 99.0 |

| Recruited or recruited/educated peersab | 60.3 | 71.7 |

| Health characteristics | 1 | |

| Current antiretroviral therapy | 69.6 | 69.7 |

| CD4 < 350 | 39.1 | 33.3 |

| Undetectable viral load | 66.1 | 66.7 |

| HIV diagnosis ≥ 10 y | 78.6 | 83.9 |

| AIDS diagnosis | 51.3 | 58.2 |

| Ever injected drugs | 30.2 | 29.3 |

| Ever had HCV | 34.5 | 29.3 |

| Prior AIDS clinical trial screening | 19.0 | 30.3 |

P < .05, χ2 test of association.

Number of peers educated/recruited also significant (P < .05, χ2 test of association).

Table 3 presents results from the logistic generalized linear mixed-model analysis. In the multivariable model, the effect of treatment condition on the probability of AIDS clinical trial screening was significant (z = 5.49, P < .001) and indicated screening was much more likely (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 55.0) among participants assigned to the intervention arm. The effect of receiving a full intervention dose was significant (z = 2.42, P < .05) and indicated that screening was more likely with a full dose (AOR = 6.7). The effect of the number of peers recruited/educated was marginally significant (z = 1.53, P = .13) and indicated that screening was more likely (AOR =1.22) among participants doing more recruiting/educating at a marginally significant level. None of the other covariates remained even marginally statistically significant in this multivariable model.

TABLE 3.

Peer-Driven Intervention Effect on Screening for an AIDS Clinical Trial: ACT2 Project, New York, NY, 2008–2009

| Predictor | Logit | SE | z | P | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

| Age | 0.0264 | 0.0209 | 1.2653 | .206 | 1.03 (0.99, 1.07) |

| Full intervention dose | 1.8955 | 0.7848 | 2.4153 | .016 | 6.66 (1.43, 30.97) |

| No. of peers recruited/educated (0—3) | 0.2026 | 0.1323 | 1.5311 | .126 | 1.22 (0.95, 1.59) |

| African American | −0.0600 | 0.5496 | −0.1091 | .913 | 0.94 (0.32, 2.77) |

| Hispanic | −0.2714 | 0.6045 | −0.4490 | .654 | 0.76 (0.23, 2.49) |

| Screened in the past | 0.5252 | 0.3409 | 1.5407 | .123 | 1.69 (0.87, 3.30) |

| Assignment to intervention arm | 4.0078 | 0.7301 | 5.4891 | < .001 | 55.02 (13.11, 229.38) |

We used a sensitivity analysis to examine the effect of the intervention arm when only the 239 non–initial-seed participants were included. Results were similar to those presented in Table 3, with a significant intervention effect (z = 5.09, P < .0001) and large adjusted odds ratio for the intervention arm (AOR = 41.8). With initial seeds excluded, full intervention dose was only marginally significant (z = 1.94, P = .05, AOR = 4.9), and both prior AIDS clinical trial screening (z = 2.10, P < .05, AOR = 2.2) and each peer recruited/educated (z = 2.06, P < .05, AOR = 1.4) were associated with an increase in the odds of clinical trial screening. A second sensitivity analysis grouped the 18 nonrecruiting initial seeds together in a single cluster. Results were no different from those presented in Table 3.

DISCUSSION

This is the first randomized controlled trial to our knowledge of a behavioral intervention to increase rates of screening for AIDS clinical trials among the population of people living with HIV/AIDS that has the greatest barriers to these clinical trials: African Americans and Hispanics. A relatively brief peer-driven intervention was highly efficacious (approximately 50% screened) in increasing screening rates compared with a time- and attention-matched control health education intervention (less than 2% screened). Importantly, the vast majority of people living with HIV/AIDS in the study had not been screened for AIDS clinical trials in the past. Because screening is the gateway to trials, increasing rates of screening among people of color living with HIV/AIDS is a critical component of ameliorating racial/ethnic disparities in clinical trials. The indirect benefits of clinical trial screening on racial/ethnic disparities in AIDS clinical trials are also potentially important. However, because there are very strict study inclusion criteria, eligibility rates for trials will be low for any population of people living with HIV/AIDS.47,48 These low rates suggest that regular and repeated screening for AIDS clinical trials is necessary to match people of color to clinical trials, and to increase or maintain their comfort with and willingness to participate in trials if found eligible in the future.

This study advances the literature on peer-driven intervention, which has not previously been applied to the problem of racial/ethnic disparities in AIDS clinical trials. Peer-driven intervention is a form of intervention that requires less staff involvement than does the typical multisession program, because participants engage in 2 forms of intervention activity independently: they are first educated by peers at the time of recruitment, and they have the opportunity to educate their own peers after the conclusion of structured intervention sessions. We found that participating in the structured intervention sessions greatly increased the odds of screening. Further, although recruiting and educating peers was only marginally significant in the main analysis, it was statistically significant both in bivariate analysis and in 1 of the sensitivity analyses, and most of those screened (71.7%) recruited and educated peers. This finding suggests that peer recruitment/education is 1 of the intervention's active ingredients. Yet because peer education takes place without staff supervision, little is known about these encounters.28 We assume that the peer recruitment/education experiences varied widely in duration and complexity. Qualitative research on participants’ recruitment and education experiences is needed to fill this gap in the literature.

Limitations of the study include a relatively short follow-up period that may under-estimate intervention efficacy because some will be screened at a later date. On the other hand, the modest attention to AIDS clinical trials in the control intervention may have magnified the intervention's true effect size. Further, this study does not make clear which intervention components are most potent in increasing the odds of screening. In future analyses, we will examine mediators of efficacy. Peer-driven intervention is considered a cost-effective intervention modality, and we will examine this cost-effectiveness in subsequent reports. Lastly, this article does not examine enrollment into AIDS clinical trials, which will be explored in future analyses. However, as noted, the proportion of people living with HIV/AIDS who are screened for AIDS clinical trials and who are found eligible tends to be low (an estimated 13–50%47,48) because trials have very restrictive inclusion and exclusion criteria. Thus, both a broad application of the intervention, and regular and repeated access to screening as described, are needed to substantially reduce racial/ethnic disparities in study enrollment.

These findings have important public health implications because they provide a method for bringing people of color living with HIV/AIDS, who experience multiple, complex, and long-standing barriers to AIDS clinical trials, into the clinical trial system. Reducing racial/ethnic disparities in AIDS clinical trials is critical for a number of reasons, including improving the ability to generalize research findings to those most affected by HIV and enabling people of color to gain access to this valuable resource. These findings also have important implications for other health conditions for which racial/ethnic disparities persist in clinical trials and other types of medical research, including HCV, cancer, and HIV vaccine research.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R01 AI070005) and the Center for Drug Use and HIV Research (P30 DA011041) at the New York University College of Nursing. The project is dedicated to the memory of Keith Cylar, co-founder and co-chief executive officer of Housing Works (1958–2004), and former Housing Works principal investigator of the ACT1 Project.

We would like to acknowledge the men and women who participated in the ACT2 Project; Usha Sharma, PhD, Program Officer, and Vanessa Elharrar, MD, Medical Officer, at the Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH; and members of the ACT2 Collaborative Research Team: Michael Aguirre, Mindy Belkin, MA, Noreen Boadi, DeShannon Guzman, ABD, Ann Marshak, Sondra Middleton, PA-C, Corinne Munoz-Plaza, MPH, Amanda Ritchie, MAA, Maya Tharaken, MSSW, Robert Quiles, and Mougeh Yasai, MA.

Human Participant Protection

Written consent was obtained from all study participants. This study was approved by the institutional review boards of the National Development and Research Institutes, Inc., Beth Israel Medical Center, and New York University.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Cases of HIV infection and AIDS in the United States and dependent areas, by race/ethnicity, 2002-2006. 2008. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/2008supp_vol13no1/pdf/HIVAIDS_SSR_Vol13_No1.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2010

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV/AIDS among Hispanics, 2004. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pubs/Facts/hispanic.htm. Accessed March 28, 2005

- 3.Oramasionwu CU, Hunter JM, Skinner J, et al. Black race as a predictor of poor health outcomes among a national cohort of HIV/AIDS patients admitted to US hospitals: a cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2009;9(1):127–139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV/AIDS among African-Americans. February 7, 2005. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pubs/Facts/afam.htm. Accessed March 28, 2005

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV/AIDS Surveillance report, 2007. 2009. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/2007report/pdf/2007SurveillanceReport.pdf. Accessed June 14, 2010

- 6.Rubin MS, Colen CG, Link BG. Examination of inequalities in HIV/AIDS mortality in the United States from a fundamental cause perspective. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(6):1053–1059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steele CB, Richmond-Reese V, Lomax S. Racial and ethnic disparities in HIV/AIDS, sexually transmitted diseases, and tuberculosis among women. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2006;15(2):116–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gifford AL, Cunningham WE, Heslin KC, et al. Participation in research and access to experimental treatments by HIV-infected patients. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1373–1382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stone V, Mauch M, Steger K, Janas S, Craven D. Race, gender, drug use, and participation in AIDS clinical trials. Lessons from a municipal hospital cohort. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(3):150–157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases HIV infection in minority populations. 2008. Available at: http://www.niaid.nih.gov/topics/HIVAIDS/Understanding/Population%20Specific%20Information/Pages/minorityPopulations.aspx. Accessed February 29, 2010

- 11.King WD, Defreitas D, Smith K, et al. Attitudes and perceptions of AIDS clinical trials group site coordinators on HIV clinical trial recruitment and retention: A descriptive study. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21(8):551–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Strategic plan for addressing health disparities: Fiscal years 2002-2006. 2002. Available at: http://www.niaid.nih.gov/healthdisparities/NIAID_HD_Plan_Final.pdf. Accessed April 26, 2006

- 13.Gwadz MV, Leonard NR, Nakagawa A, et al. Gender differences in attitudes toward AIDS clinical trials among urban HIV-infected individuals from racial and ethnic minority backgrounds. AIDS Care. 2006;18(7):786–794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wendler D, Kington R, Madans J, et al. Are racial and ethnic minorities less willing to participate in health research? PLoS Med. 2006;3(2): e19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wynia MK, Gamble VN. Mistrust among minorities and the trustworthiness of medicine. PLoS Med. 2006;3(5):e244; author reply e245. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Priddy FH, Cheng AC, Salazar LF, Frew PM. Racial and ethnic differences in knowledge and willingness to participate in HIV vaccine trials in an urban population in the Southeastern US. Int J STD AIDS. 2006;17(2):99–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slomka J, Ratliff EA, McCurdy SA, Timpson S, Williams ML. Decisions to participate in research: Views of underserved minority drug users with or at risk for HIV. AIDS Care. 2008;20(10):1224–1232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stone VE, Mauch MY, Steger KA. Provider attitudes regarding participation of women and persons of color in AIDS clinical trials. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1998;19(3):245–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andersen JW, Fass R, van der Horst C. Factors associated with early study discontinuation in AACTG studies, DACS 200. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007;28(5):583–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown-Peterside P, Chiasson MA, Ren L, Koblin BA. Involving women in HIV vaccine efficacy trials: Lessons learned from a vaccine preparedness study in New York City. J Urban Health. 2000;77(3):425–437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schuster MA, Kanouse DE, Morton SC, et al. HIV-infected parents and their children in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(7):1074–1081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gwadz MV, Cylar K, Leonard NR, et al. An exploratory behavioral intervention trial to improve rates of screening for AIDS clinical trials among racial/ethnic minority and female persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(3):639–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freedberg KA, Sullivan L, Georgakis A, Savetsky J, Stone V, Samet JH. Improving participation in HIV clinical trials: Impact of a brief intervention. HIV Clin Trials. 2001;2(3):205–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heckathorn DD. Collective sanctions and compliance norms: A formal theory of group-mediated social control. Am Sociol Rev. 1990;55:366–384 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heckathorn DD. Collective action and group heterogeneity: Voluntary provision versus selective incentives. Am Sociol Rev. 1993;58:329–350 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Broadhead RS, Heckathorn DD, Weakliem DL, et al. Harnessing peer education networks as an instrument for AIDS prevention. Public Health Rep. 1998;113(Suppl 1):42–57 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heckathorn DD, Broadhead RS, Anthony DL, Weakliem DL. AIDS and social networks: HIV prevention through network mobilization. Sociol Focus. 1999;32:159–179 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Broadhead RS, Heckathorn DD, Altice FL, et al. Increasing drug users’ adherence to HIV treatment: Results of a peer-driven intervention feasibility study. Soc Sci Med. 2002;55(2):235–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cottler LB, Compton WM, Ben-Abdallah A, Horne M, Claverie D. Achieving a 96.6 percent follow-up rate in a longitudinal study of drug abusers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1996;41(3):209–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flay B, Petraitis J. The theory of triadic influence. : Albrecht G, Advances in Medical Sociology. Vol IV Greenwich, CT: JAI Press; 1994:19–44 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heckathorn DD. Respondent-driven sampling: A new approach to the study of hidden population. Soc Probl. 1997;44(2):174–199 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hettema J, Steele J, Miller WR. Motivational interviewing. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:91–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller W, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change. 2nd ed New York, NY: Guilford; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ewart CK. Social action theory for a public health psychology. Am Psychol. 1991;46(9):931–946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abdul-Quader AS, Heckathorn DD, McKnight C, et al. Effectiveness of respondent-driven sampling for recruiting drug users in New York City: Findings from a pilot study. J Urban Health. 2006;83(3):459–476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Semaan S, Lauby J, Liebman J. Street and network sampling in evaluation studies of HIV risk-reduction interventions. AIDS Rev. 2002;4:213–223 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang J, Carlson R, Falck R, Siegal H, Rahman A, Li L. Respondent-driven sampling to recruit MDMA users: A methodological assessment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;78(2):147–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Questionnaire Development System. Bethesda, MD: Nova Research Company; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Des Jarlais D, Paone D, Milliken J, et al. Audio-computer interviewing to measure HIV risk behaviour among injecting drug users: A quasi-randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;353(9165):1657–1661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study Baseline Questionnaire. Fact Sheet. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 42.National Institute on Drug Abuse Risk Behavior Assessment. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kalichman SC, Rompa D, Cage M, et al. Effectiveness of an intervention to reduce HIV transmission risks in HIV-positive people. Am J Prev Med. 2001;21(2):84–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCulloch CE, Searle SR. Generalized, Linear, and Mixed Models. New York, NY: Wiley; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bates D, Maechler M. lme4: Linear mixed-effects models using S4 classes. R package version 0.999375-32. 2009. Available at: http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=lme4. Accessed January 11, 2010

- 46.R Development Core Team R: A language and environment for statistical computing. 2009. Available at: http://www.r-project.org. Accessed February 12, 2009

- 47.Gandhi M, Ameli N, Bacchetti P, et al. Eligibility criteria for HIV clinical trials and generalizability of results: The gap between published reports and study protocols. AIDS. 2005;19(16):1885–1896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marshak A, Costantini G, Middleton S, et al. Screening for AIDS clinical trials in the project ACT cohort of racial/ethnic minorities and women in New York City: substantial interest but low eligibility. Poster presented at: 4th International AIDS Society Conference; July 2007; Sydney, Australia [Google Scholar]