Abstract

Objectives. We sought to provide data-based estimates of sexual violence in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and describe risk factors for such violence.

Methods. We used nationally representative household survey data from 3436 women selected to answer the domestic violence module who took part in the 2007 DRC Demographic and Health Survey along with population estimates to estimate levels of sexual violence. We used multivariate logistic regression to analyze correlates of sexual violence.

Results. Approximately 1.69 to 1.80 million women reported having been raped in their lifetime (with 407 397–433 785 women reporting having been raped in the preceding 12 months), and approximately 3.07 to 3.37 million women reported experiencing intimate partner sexual violence. Reports of sexual violence were largely independent of individual-level background factors. However, compared with women in Kinshasa, women in Nord-Kivu were significantly more likely to report all types of sexual violence.

Conclusions. Not only is sexual violence more generalized than previously thought, but our findings suggest that future policies and programs should focus on abuse within families and eliminate the acceptance of and impunity surrounding sexual violence nationwide while also maintaining and enhancing efforts to stop militias from perpetrating rape.

Violence against women, often used as a systematic tactic of war to destabilize populations and destroy community and family bonds,1 has become more common and increasingly brutal in recent years in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Reports from the DRC indicate that sexual violence is widespread and includes gang rape, abduction for purposes of sexual slavery, forced participation of family members in rape, and mutilation of women's genitalia with knives and guns, among other atrocities. Reports from the popular press, peer-reviewed publications, and multinational and nongovernmental organizations describe the number of rape victims in the DRC as “tens of thousands” in a country with an estimated population approaching 70 million.1–7

According to the DRC Minister for Gender, Family, and Children, more than 1 million of the country's women and girls are victims of sexual violence.1 The United Nations Population Fund noted that 15 996 new cases of sexual violence were reported in the DRC in 2008 and that 65% of the victims were children and adolescents younger than 18 years, with 10% of all victims younger than 10 years.1,8 Most reports of sexual violence in the DRC are related to incidents occurring as part of the ongoing armed conflict in the country, the majority of which has been concentrated in the eastern provinces of Nord-Kivu and Sud-Kivu, bordering Rwanda; however, there has also been substantial unrest in neighboring provinces, including Maniema and Katanga.

Despite the alleged severity of violence against women in the DRC and the attention it receives in the popular press, little research provides data-based estimates of the magnitude or nature of the problem. Reliable, nationally representative estimates of rape and sexual violence in the DRC do not exist. Consequently, although attention to sexual violence in the DRC has escalated in the past 5 years, nearly all estimates of sexual violence include the disclaimer that the “actual magnitude of violence is unknown,” and it is in all likelihood much higher than the best estimates offered.

As expected, estimates drawn from data-based calculations published in the past decade (2000–2010) are few (Table 1). With 2 exceptions,9,10 all of the studies focused on limited geographic regions of the DRC. Of those focusing on particular regions, the most comprehensive estimates come from reports of rape registered with Malteser International, a nongovernmental organization that conducts medical and social support programs in Sud-Kivu.11 Findings indicate that approximately 20 500 women and girls were raped in the 2-year period from January 2005 to December 2007. Also in Sud-Kivu, among 492 women and girls who had experienced sexual violence, nearly 80% of cases were gang rapes, and 12.4% involved the insertion of objects into the genitalia.12

TABLE 1.

Studies Providing Data-Based Estimates of Sexual Violence in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), 2000–2010

| Study | Time Period | Geographic Focus | Data Source/Methodology | Type(s) of Sexual Violence Assessed | Results |

| Harvard Humanitarian Initiative14 | 1991–2008 (time of assault), 2004–2008 (presentation at hospital) | Bukavu, Sud-Kivu | Retrospective cohort study at Panzi Hospital; nonsystematic convenience sample used to select women as they presented at the hospital's program for victims of sexual violence (an additional 4709 women accessed postviolence care but were not interviewed) | General sexual violence, sexual assault, gang rape, sexual slavery | 4311 records reviewed; 52% of women identified armed combatants as perpetrators; total number of assaults decreased over study period, but number of civilian rapes increased 17-fold (from 1% of total reports in 2004 to 38% of total reports in 2008); 56% of attacks occurred in victim's home, and mean number of assailants was 2.5 |

| Longombe et al.13,a | April 2003–June 2006 | Goma, Nord-Kivu | Record review at the Doctors on Call for Service/HEAL Africa Hospital screening for fistula and rape co-occurrence | Rape, general sexual violence, forcing of crude objects into the vagina | 4715 cases among women and girlsb |

| Ministry of Planning17 | January–August 2007 | DRC | Demographic and Health Survey (household-based survey collection, nationally representative of women aged 15–49 y) | Forced sex, forced sex with intimate partner, first sexual experience forced | 16% of women experienced forced sex (4% in preceding 12 months); first sexual experience of 9.9% of women was forced; 35% of women experienced forced sex with intimate partner |

| Ohambe et al.12 | September–December 2003 | Sud-Kivu | Focus groups and in-depth interviews; participants identified through network or snowball sampling; review of supporting documentation from local organizations | Rape, sexual abuse, gang rape, rape involving the insertion of objects into victim's genitals | Of 492 women and girls aged 12–70 y, 21.3% had been raped, 79% had experienced gang rape, and 12.4% had experienced rape involving insertion of objects into their genitals |

| Onsrud et al.15,a | November 2005–November 2007 | Bukavu, Sud-Kivu | Record review of patients receiving fistula treatment at Panzi Hospital to screen for fistula and rape co-occurrence | Rape, gang rape, general sexual violence | 24 of 604 fistula patients (4%) aged 3 to 45 y reported co-occurrence of rape |

| Pham et al.16,a | September–December 2007 | Nord-Kivu, Sud-Kivu, Ituri district of Orientale | Multistage random cluster household survey of 2620 adult male and female residentsc | Sexual violation | 396 participants reported sexual violation (15.8% of all reporting men and women) |

| Steiner et al.11,a | January 2005–December 2007 | Sud-Kivu | Rapes registered to the Malteser International medicosocial support program (specialized health centers and community-based organizations) via document extraction | Rape | 20 517 women and girls reported rape, and 66% of patients in 2005 were treated for sexually transmitted infectionsd |

| Taback et al.9,a | October 2005–March 2007 | DRC (60% of reports were from Sud-Kivu, Orientale, and Nord-Kivu) | Monthly human rights reports from the United Nations Organization Mission in DRC, based on interviews conducted with abused individuals and with witnesses | General sexual violence | 218 reports involving 500 abused individuals; 210 patients (96%) were female, and 62 (30%) were female minors; of 44 reports involving the police, 50% occurred in custody |

| Van Herp et al.10,a | 1998–2000 and 2001 | 5 survey sites in Équateur Katanga, Bas-Congo, and Bandundu | Household survey involving 2-stage random cluster sample design | Sexual abuse | 188 cases from 3620 households (approximately 5%) |

Study published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal; time periods refer to timing of fieldwork but often do not correspond to the time period in which violence was experienced.

Age ranges examined were not specified, however, the youngest mentioned victim was 6 years old, whereas the oldest was 66 years old.

It is unclear how the authors defined “adult.” Note that this is the same survey used by Vinck et al.,44 and thus we do not repeat as separate studies.

Mean age values are not specified, but a figure graphically suggests that ages ranged from 11 to 70 years, with a majority of women falling into the 21- to 30-year age category.

Studies involving hospital record reviews revealed 4715 cases of rape in Nord-Kivu13 and 4311 and 24 in Sud-Kivu14,15 depending on sampling strategy and study period (note that the participants in the latter 2 studies were fistula patients, and therefore the sample was a selected one). In 2 additional site-specific studies, household surveys revealed rates of sexual violence ranging approximately from 5% to 16%.10,16

In a study involving nationwide data, monthly human rights reports of the United Nations Peacekeeping Force from October 2005 to March 2007 identified 500 abused individuals, of whom 96% were female and 30% were female minors.9 The final technical report of the 2007 DRC Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) indicates that, nationally, 9.9% of women aged 15 to 49 years reported that their first sexual encounter was against their will, 4.2% reported having sex against their will in the preceding 12 months, and 16% reported ever having had sex against their will.17 Although the report disaggregated mean values by background characteristics and provinces, no statistical analyses were conducted to explore how sexual violence was distributed according to socioeconomic and demographic characteristics or province or to relate mean values to population estimates.

Using data from the 2007 DRC Demographic and Health Survey, we sought to fill the gap in empirical research by providing data-based estimates and determinants of rape and intimate partner sexual violence (IPSV) in the DRC. First, we hypothesized that previous estimates of sexual violence that typically relied on facility data or police reports would be gross underestimates of the sexual violence rates found in population-based data. Second, we hypothesized that women residing in Nord-Kivu and Sud-Kivu would face a significantly increased risk of sexual violence as a result of the high levels of armed conflict in these provinces in recent years. Finally, because the literature suggests increases in societal tolerance of and exposure to violence,12,18,19 we hypothesized that IPSV levels would be a major contributing factor to violence against women in the DRC.

METHODS

DHSs are cross-country population-level household surveys administered by host country governments with funding and technical assistance from Macro International and the United States Agency for International Development. These surveys have been conducted in more than 84 countries since the early 1980s and are widely used to provide policymakers and health professionals with health, nutrition, and population data in fields such as fertility, sexual behavior, family planning, nutrition, HIV, and mortality (further information on sampling and questionnaire design is available at http://www.measuredhs.com).

The 2007 DRC Demographic and Health Survey, the first such data collection effort in the DRC, was fielded from January to August of 2007 in collaboration with the Ministry of Planning and with support from the Ministry of Health. The final sample included 9995 women aged 15 to 49 years from all 11 provinces. In addition, a randomly assigned module for domestic violence was used to collect information on sexual violence from a subsample of 3436 women.

Population Estimates

The most recent DRC census was conducted in 1984. Therefore, current population estimates are imprecise and suffer from several limitations. Conflict and migration have skewed natural population increases, and current estimates cannot take these factors into account completely until a new census is conducted. To account for these data limitations, we replicated our analyses using 2 sources of current population estimates.

The first data source provided population projections for 2006 calculated by the National Institute of Statistics; these estimates were included in the national annual health report (Annuaire Sanitaire) in 2008.20 The second source, based on the projected population in 2007, was the Expanded Program on Immunization (Program Élargi de Vaccination [PEV]); the figures from this source are the official figures used by the Ministry of Health.21

Outcome Measures

The DHS began collecting data on indicators of intimate partner and other sexual violence in the early 1990s, and comparable information on the prevalence of violence against women is available in more than 30 countries. These data are regarded as a high-quality source of information on levels of sexual violence, risk factors, and relationships with adverse health outcomes and have been widely published in peer-reviewed journals. The DRC Demographic and Health Survey asked several questions to measure sexual violence perpetrated by intimate partners and others, enabling us to construct 3 indicators capturing various typologies of sexual violence.

All women interviewed for the sexual violence module were asked “Has anyone ever forced you to have sexual relations with them against your will?” This question was asked in reference to both lifetime experiences and experiences in the preceding 12 months. All women were also asked “Was your first sexual encounter against your will (forced)?” Women who responded yes to either of these questions were defined as having a history of being raped, and all women who reported having been raped in the preceding 12 months were included in the 12-month category. Finally, all women who had ever been married or had cohabited were asked “Has your partner ever physically forced you to have sex or perform sexual acts against your will?” Women who responded that they had “often” or “sometimes” been forced to engage in these acts were defined as having experienced IPSV. We used the data collected during this survey to examine 3 classifications of sexual violence: history of rape, rape in the preceding 12 months, and history of IPSV. However, we chose women selected for the domestic violence module for consistency in weighting and subsample across our outcomes. A sensitivity analysis using alternate samples is included in the Appendix available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org.

Statistical Models

To calculate estimates of the total number of women experiencing sexual violence, we used population estimates from the Annuaire Sanitaire and the PEV and performed calculations as follows for each. Initially, we calculated 5-year age-specific proportions of women reporting the 3 types of sexual violence assessed. Then we multiplied the proportion reporting each type of sexual violence by the estimated number of women in each 5-year age interval. We used appropriate weights (equivalent to 1 woman aged 15–49 years randomly selected per household) to account for the complex survey design of the DHS. To estimate the total number of women in the 15- to 49-year age category, we used proportions from the Annuaire Sanitaire, the only data source that provides this information. We derived the national age-specific population distribution from the Annuaire Sanitaire and assumed the same age distribution across all provinces.

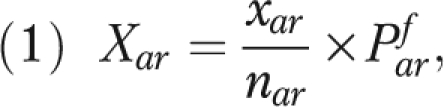

The equation used to determine age-specific counts of each type of sexual violence can be modeled as follows:

|

where xar is the number of women in province r in age interval a reporting sexual violence type x (having ever been raped, having been raped in the preceding 12 months, or having experienced IPSV) and nar is the total number of women in province r in age interval a included in the survey.  is the total population of women in age interval a in province r, and Xar is the count of sexual violence type x for age group a in province r.

is the total population of women in age interval a in province r, and Xar is the count of sexual violence type x for age group a in province r.

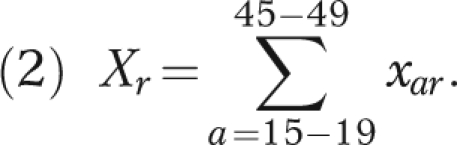

We summed each age-specific, provincial count of sexual violence estimates to obtain provincial totals:

|

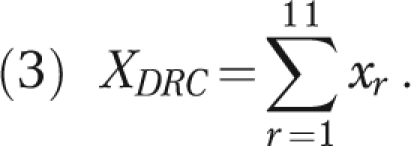

We then summed the 11 provincial totals to produce a national estimate of each type of sexual violence:

|

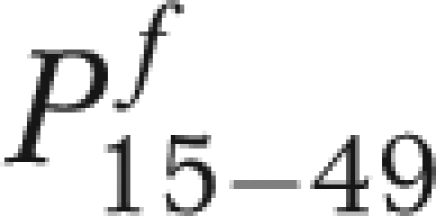

Finally, we determined provincial and national rates per 1000 women of reproductive age:

where X is the total estimate of each specific type of sexual violence in the province (or the country as a whole) and  is the total population of women of reproductive age (15–49 years) in the province (or country). This analysis was used to test our 2 hypotheses regarding the total number of women reporting sexual violence as well as the relative share of IPSV in determining the overall estimates.

is the total population of women of reproductive age (15–49 years) in the province (or country). This analysis was used to test our 2 hypotheses regarding the total number of women reporting sexual violence as well as the relative share of IPSV in determining the overall estimates.

In addition, we used multivariate logistic regression models to predict women's probability of experiencing sexual violence and to investigate, among other factors, whether characteristics such as region of residence were correlated with this probability, consistent with our hypotheses:

In equation 5, the probability of experiencing sexual violence is a function of individual-level variables Xi, specifically age (coded as 5-year age splines) and educational attainment (coded as no schooling, primary education, or secondary education or higher); household-level variables Xh (wealth quintiles); and locational variables Xr (urban–rural residence and province). Wealth quintiles were precomputed in the DHS data set through factor analyses of background indicators of socioeconomic status such as dwelling characteristics, asset ownership, and access to basic infrastructure.22 Standard errors were clustered at the primary sampling unit to control for unobserved community-level factors that might influence sexual violence. We used Stata version 11 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) to conduct our analyses.

RESULTS

Table 2 shows the summary results of the calculations of the total number of women reporting sexual violence by province. Total population figures for the country ranged from 63.27 million (according to Annuaire Sanitaire estimates) to 66.97 million (according to PEV estimates). The total number of women in DRC reporting IPSV ranged from 3.07 million to 3.37 million, and occurrences of IPSV were particularly high in the provinces of Equateur Bandundu, Katanga, and Kasai-Oriental.

TABLE 2.

Summary of Demographic Calculations of Levels and Rates of Sexual Violence Among Women Aged 15–49 Years, by Province: Democratic Republic of Congo, 2007

| Absolute No. of Occurrences | Rates per 1000 Women of Reproductive Age | |||||||

| Province | Provincial Population | No. of Women of Reproductive Age | Intimate Partner Sexual Violence | History of Rape | Rape in Preceding 12 Mo | Intimate Partner Sexual Violence | History of Rape | Rape in Preceding 12 Mo |

| Annuaire Sanitaire calculations | ||||||||

| Bandundu | 7 228 000 | 1 592 537 | 455 207 | 154 883 | 22 691 | 286 | 97 | 14 |

| Bas-Congo | 4 098 000 | 902 908 | 100 960 | 78 005 | 6504 | 112 | 86 | 7 |

| Equateur | 6 602 000 | 1 454 611 | 606 200 | 219 982 | 94 604 | 417 | 151 | 65 |

| Kasai-Occidental | 4 616 000 | 1 017 038 | 252 678 | 140 072 | 7749 | 248 | 138 | 8 |

| Kasai-Oriental | 5 610 000 | 1 236 045 | 307 089 | 82 232 | 9418 | 248 | 67 | 8 |

| Katanga | 9 297 000 | 2 048 397 | 340 179 | 164 887 | 28 784 | 166 | 80 | 14 |

| Kinshasa | 7 596 000 | 1 673 618 | 202 761 | 207 512 | 43 619 | 121 | 124 | 26 |

| Maniema | 1 730 000 | 381 169 | 93 305 | 55 818 | 19 050 | 245 | 146 | 50 |

| Nord-Kivu | 4 947 000 | 1 089 967 | 260 402 | 223 262 | 73 387 | 239 | 205 | 67 |

| Orientale | 7 221 000 | 1 590 995 | 310 454 | 242 536 | 59 779 | 195 | 152 | 38 |

| Sud-Kivu | 4 281 000 | 943 228 | 143 758 | 120 709 | 41 811 | 152 | 128 | 44 |

| Total | 63 226 000 | 13 930 513 | 3 072 994 | 1 689 899 | 407 397 | 221 | 121 | 29 |

| Program Élargi de Vaccination calculations | ||||||||

| Bandundu | 6 753 173 | 1 487 919 | 425 304 | 144 708 | 21 200 | 286 | 97 | 14 |

| Bas-Congo | 2 839 236 | 625 566 | 69 948 | 54 045 | 4506 | 112 | 86 | 7 |

| Equateur | 7 552 674 | 1 664 072 | 693 491 | 251 659 | 108 227 | 417 | 151 | 65 |

| Kasai-Occidental | 6 296 054 | 1 387 203 | 344 644 | 191 054 | 10 569 | 248 | 138 | 8 |

| Kasai-Oriental | 7 996 374 | 1 761 832 | 437 719 | 117 212 | 13 424 | 248 | 67 | 8 |

| Katanga | 9 629 888 | 2 121 742 | 352 359 | 170 791 | 29 815 | 166 | 80 | 14 |

| Kinshasa | 6 013 040 | 1 324 846 | 160 507 | 164 267 | 34 529 | 121 | 124 | 26 |

| Maniema | 1 792 626 | 394 967 | 96 683 | 57 839 | 19 740 | 245 | 146 | 50 |

| Nord-Kivu | 5 410 882 | 1 192 173 | 284 820 | 244 197 | 80 269 | 239 | 205 | 67 |

| Orientale | 8 302 959 | 1 829 382 | 356 971 | 278 877 | 68 736 | 195 | 152 | 38 |

| Sud-Kivu | 4 379 129 | 964 848 | 147 053 | 123 476 | 42 769 | 152 | 128 | 44 |

| Total | 66 966 036 | 14 754 551 | 3 369 499 | 1 798 125 | 433 785 | 228 | 122 | 29 |

Note. Figures reflect summaries of more detailed calculations by province (see the Appendix, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Intimate partner sexual violence was calculated among women aged 15 to 49 years who had ever been married or had cohabited, with adjustment to reflect the proportions of married women by age group and province derived from the Demographic and Health Survey. To maintain consistency with population breakdowns in the Annuaire Sanitaire, we included women aged 15 to 17 years in the denominator even though they were not asked about lifetime rape and rape in the past 12 months; this inclusion resulted in conservative estimates for this age group.

Approximately 1.69 to 1.80 million women aged 15 to 49 years had a history of being raped; the absolute number of such occurrences was highest in the Orientale province, followed by Nord-Kivu and Équateur. In the 12 months prior to the survey, the number of women who had been raped ranged from 407 397 to 433 785, and again the highest absolute numbers were in Équateur Orientale, and Nord-Kivu. The highest rate of lifetime rape (per 1000 women of reproductive age) was in the Nord-Kivu province, followed by Orientale and Équateur. The highest rate of rape in the preceding 12 months was in the Nord-Kivu province, followed by Équateur and Maniema. The lowest rates of lifetime rape were found in the provinces of Bas-Congo, Kasai-Oriental, and Katanga, whereas the lowest rates of rape in the preceding 12 months were found in Bas-Congo, Kasai-Oriental, and Kasai-Occidental.

Finally, rates of IPSV were highest in the Equateur, Kasai-Orientale, and Bandundu provinces, whereas rates were lowest in the Bas-Congo, Kinshasa, and Sud-Kivu provinces. More detailed tables, with results shown by province, are included in the Appendix available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org.

Table 3 shows the results of logit regression models predicting IPSV, history of rape, and rape in the preceding 12 months. Coefficients are reported as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Most of the 3436 women who answered the sexual violence questions were 15 to 29 years old, had at least some secondary schooling, and lived in rural areas. Descriptive statistics for control variables in the full sample and among the women who had ever been married or had cohabited are presented in Appendix Table A1 (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Provincial indicators showed that, after other factors (age, education, wealth, and urbanicity) had been held constant, women (with a current or past intimate partner) residing in the provinces of Equateur, Nord-Kivu, Maniema, Kasai-Oriental, and Kasai-Occidental were significantly more likely to report IPSV than were women residing in Kinshasa, whereas women in Bas-Congo were significantly less likely to do so.

TABLE 3.

Logit Models Predicting Sexual Violence Among Women Aged 15–49 Years: Democratic Republic of Congo, 2007

| Characteristic | Intimate Partner Sexual Violencea (n = 2859), OR (95% CI) | History of Rape (n = 3436), OR (95% CI) | Rape in the Preceding 12 Mo (n = 3436), OR (95% CI) |

| Age group, y (ref: 15–19 y) | |||

| 20–24 | 0.80 (0.58, 1.10) | 2.54** (1.70, 3.80) | 2.22* (1.06, 4.69) |

| 25–29 | 0.92 (0.65, 1.29) | 3.22** (2.11, 4.92) | 2.51* (1.20, 5.23) |

| 30–34 | 0.91 (0.64, 1.30) | 2.55** (1.65, 3.93) | 2.97** (1.42, 6.22) |

| 35–39 | 0.78 (0.54, 1.12) | 4.27** (2.76, 6.61) | 3.49** (1.56, 7.84) |

| 40–44 | 0.57** (0.38, 0.84) | 3.19** (1.94, 5.22) | 2.25 (0.87, 5.81) |

| 45–49 | 0.71 (0.47, 1.07) | 2.70** (1.57, 4.64) | 1.56 (0.53, 4.60) |

| Educational level (ref: no education) | |||

| Primary | 1.00 (0.80, 1.24) | 1.09 (0.80, 1.48) | 1.54 (0.92, 2.58) |

| Secondary or above | 0.95 (0.72, 1.26) | 1.31 (0.93, 1.86) | 1.20 (0.62, 2.30) |

| Wealth quintile (ref: bottom quintile) | |||

| Second | 0.92 (0.72, 1.18) | 0.77 (0.55, 1.10) | 0.78 (0.41, 1.46) |

| Third | 0.80 (0.60, 1.07) | 0.61* (0.42, 0.90) | 0.58 (0.29, 1.15) |

| Fourth | 0.95 (0.67, 1.36) | 0.98 (0.62, 1.54) | 1.06 (0.46, 2.42) |

| Fifth | 0.98 (0.62, 1.54) | 0.71 (0.42, 1.20) | 0.71 (0.26, 1.92) |

| Urban residence (ref: rural) | 1.04 (0.74, 1.45) | 1.10 (0.75, 1.61) | 1.15 (0.55, 2.41) |

| Province (ref: Kinshasa) | |||

| Bandundu | 1.24 (0.74, 2.08) | 0.74 (0.41, 1.31) | 0.92 (0.29, 2.94) |

| Bas-Congo | 0.59* (0.37, 0.93) | 0.55* (0.31, 1.00) | 0.44 (0.12, 1.65) |

| Equateur | 3.07** (1.84, 5.13) | 1.33 (0.73, 2.42) | 2.36 (0.75, 7.45) |

| Kasai-Occidental | 2.85** (1.72, 4.72) | 1.44 (0.83, 2.50) | 1.42 (0.44, 4.54) |

| Kasai-Oriental | 1.55* (1.00, 2.41) | 0.57 (0.31, 1.05) | 0.61 (0.18, 2.12) |

| Katenga | 1.11 (0.66, 1.84) | 0.65 (0.36, 1.17) | 1.16 (0.37, 3.63) |

| Maniema | 1.62 (0.92, 2.85) | 1.38 (0.81, 2.34) | 1.99 (0.70, 5.64) |

| Nord-Kivu | 2.02** (1.21, 3.37) | 1.78* (1.09, 2.92) | 3.27* (1.25, 8.53) |

| Orientale | 1.02 (0.63, 1.63) | 1.19 (0.68, 2.10) | 1.88 (0.60, 5.87) |

| Sud-Kivu | 0.98 (0.60, 1.58) | 1.22 (0.70, 2.12) | 2.35 (0.81, 6.83) |

Note. CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio. Standard errors (not reported) were clustered at the primary sampling unit level.

*P < .05; **P < .01.

Among women aged 15 to 49 years who had ever been married or had cohabited.

A different pattern emerged among risk factors for history of rape and for rape in the preceding 12 months. Women residing in Nord-Kivu were significantly more likely than were women in Kinshasa to report a history of rape (OR = 1.78; 95% CI = 1.09, 2.92), whereas women residing in Bas-Congo (OR = 0.55; 95% CI = 0.31, 0.99) and Kasai-Oriental (OR = 0.57; 95% CI = 0.31, 1.05) were significantly less likely to do so. The disparity between Nord-Kivu and Kinshasa was even greater among women reporting that they had been raped in the preceding 12 months (OR = 3.3; 95% CI = 1.25, 8.53). Relative to the reference group (women aged 15–19 years), older women were more likely to report a history of rape or rape in the preceding 12 months. No other factors consistently predicted rape, including education, wealth, and urban residence.

DISCUSSION

Our results indicate that the number of women who have been the victims of rape and IPSV in the DRC is several orders of magnitude higher than what has been cited in previous studies. For example, estimates of rape among women aged 15 to 49 years in the 12 months prior to the survey translate into approximately 1150 women raped every day, 48 women raped every hour, and 4 women raped every 5 minutes. The implied underestimation of the results of previous studies, which were based on reports from police departments and hospitals where victims seek medical care, should not be surprising given that only a small proportion of women seek treatment of or report sexual violence. For example, past research indicates that only 7% of women experiencing physical or sexual violence in the 1999 East Timor conflict reported it to authorities,23 and only 6% of rape victims during the Rwanda genocide sought medical treatment.24–26

Furthermore, because our data did not capture sexual violence among women and girls younger than 15 years or older than 49 years and did not include sexual violence among boys and men, even our estimates are a lower bound of the true prevalence of sexual violence. Although the burden of sexual violence among these groups is uncertain, a review of the records of 4133 women attending Panzi Hospital in Sud-Kivu showed that 6% were younger than 16 years and 10% were older than 65 years.14

In addition, Human Rights Watch reported that sexual violence in 2009 doubled in comparison with 2008.27 If this assessment is accurate, then the current prevalence of sexual violence is likely to be even higher than our estimates suggest, given that our estimates were derived from survey data collected in 2007. As a further robustness check (data not presented), we reran our analysis with PEV population estimates for 2009 to project our baseline figures to that year. Our results correspond to 3.58 million women reporting IPSV, 1.92 million reporting a history of rape, and 462 293 reporting rape in the preceding 12 months.

Another major finding is the relative magnitude of IPSV in comparison with general rape indicators. Media attention tends to focus on sexual violence allegedly committed by paramilitary personnel and soldiers. To a lesser extent, attention is given to sexual violence perpetrated by men from local communities who, reports indicate, often join the military on rape raids3 or exploit the conflict to sexually assault women without fear of punishment.8,26 The United Nations has also opened investigations into the behavior of its own peacekeepers amid allegations of rape and engagement of local women in “survival sex” and transactional sex.28

Less visible, however, is the prevalence of IPSV, which our analysis shows to be extraordinarily high. Specifically, we found that the number of women reporting IPSV was roughly 1.8 times the number of women reporting rape (221 and 121 per 1000 women of reproductive age, respectively). This result is in line with international research indicating that intimate partner sexual violence is the most pervasive form of violence against women.29 However, DHS evidence suggests that this is a particularly large problem in the DRC. For example, whereas the percentage of women reporting IPSV in the DRC was approximately 35%, estimates for neighboring countries are only 12% in Rwanda (2005 DHS), 12% in Zimbabwe (2005–2006 DHS), 13% in Malawi (2004 DHS), and 15% in Kenya (2003 DHS).17,30 Interestingly, the provinces with the highest rates of rape (Equateur, Orientale, Nord-Kivu, Sud-Kivu, and Maniema) were different from those with the highest rates of IPSV (Equateur, Bandundu, and Kasai-Oriental) with the exception of Equateur, which is not in the eastern conflict region.

The final 2 major findings emerge from the logistic regression analysis: first, few background factors significantly predicted sexual violence (apart from age), and, second, Nord-Kivu was the only province in which women were significantly more likely to report all 3 types of sexual violence than were women in Kinshasa after other factors had been held constant. The latter finding partially confirms our second hypothesis, namely that women in the most conflict-affected provinces of Nord-Kivu and Sud-Kivu would be at increased risk of sexual violence. Although the rate of rape in the preceding 12 months among women in Sud-Kivu was relatively high, the rate was only the fourth highest overall for this indicator, and the province's rate of ISPV was among the lowest.

The finding that few background factors predicted sexual violence suggests that such violence is somewhat random with respect to the observable characteristics included in the logistic regression analysis. Women's education, level of wealth, and area of residence (urban vs rural) did not protect them from sexual violence, nor did these factors place them more at risk for sexual violence. These findings were not unexpected given that the literature on relationships between violence against women, wealth, education, and other measures of women's status has shown mixed results.30–33 Direct policy implications of these findings point to the importance of considering geographically diverse interventions rather than narrow targeting of marginalized women (i.e., those who are poor or less educated) or those living in rural areas or areas of conflict.

Limitations

Our study involved a number of inevitable limitations, mainly arising from the use of household-based population-level sampling. For example, we did not have data on individuals who had migrated out of the country, who were internally displaced, or who had died as a result of violence.10,34 This is of special concern for our research topic given that internal displacement, migration, and violent death are likely to be highly correlated with experiences of sexual violence.35

Another limitation is the assumption of the same age and sex population distribution across all provinces, which will not hold if conflict-related mortality has led to skewed sex distributions. Common to all household-based surveys that solicit information on violence against women is underreporting as a result of stigma, shame, and fear of disclosure to partners or authorities. For example, evidence suggests that large-scale multipurpose surveys such as the DHS are likely to undercount violence estimates compared with household surveys in which there is a specific focus on violence and in which interviewers are specially trained in interviewing in this field.36,37 Taken together, these limitations suggest that our estimates should be considered a lower-bound approximation of the true situation in the DRC.

Policy Implications

The implications of an epidemic of sexual violence of this magnitude for the health and well-being of residents of the DRC have not gone unnoticed by the government or the multitude of domestic and international organizations working on sexual violence issues. In August 2009, US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton visited eastern DRC to highlight the problem of violence against women, calling it the “worst example of man's inhumanity to women” and demanding the arrest and punishment of those responsible.38 During this visit, the United States pledged $17 million to help fight the epidemic of rape. Other governments (e.g., Canada and Belgium) have pledged similarly large levels of funding.1

Many governments channel funding through international organizations, but a more aggressive, mainstreamed effort is needed. Unique among sub-Saharan African countries, Article 15 of the DRC's constitution specifically mentions sexual violence and stipulates that “public authorities [will] ensure the elimination of sexual violence.”39–41 Marital rape, however, is not a prosecutable offense in the DRC, despite the country having passed new legislation on sexual violence as recently as 2006.40

Recommending specific measures that the DRC government should consider to tackle the problem of rape and sexual violence is beyond the scope of this article. We refer readers to recent literature that has offered a number of concrete steps that can be taken by the government, the private sector, and the international community.1,42–45

However, one weapon in the arsenal needs to be a better understanding of the magnitude of the problem. We have provided data-driven estimates that will enable domestic policymakers, international organizations, and donors to allocate existing resources more efficiently, lobby more effectively for additional resources for the appropriate types of interventions, and, in general, make better policy and programmatic choices. Taken together, our results suggest that future policies and programs should also strengthen their focus on abuse within families and eliminate the acceptance of and impunity surrounding sexual violence while maintaining and enhancing efforts to stop militias from perpetrating rape.

Acknowledgments

We thank Megan Todd for assistance with figures in an earlier version and Patrick Mullen for helpful comments on a draft of the article.

Human Participant Protection

The Demographic and Health Survey data used in this study are publicly available, and thus no protocol approval was needed.

References

- 1.Soldiers Who Rape, Commanders Who Condone: Sexual Violence and Military Reform in the Democratic Republic of Congo. New York, NY: Human Rights Watch; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bastick M, Grimm K, Kunz R. Sexual Violence in Armed Conflict: Global Overview and Implications for the Security Sector. Geneva, Switzerland: Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bosmans M. Challenges in aid to rape victims: the case of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Essex Hum Rights Rev. 2007;4(1):1–12 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanlon H. Implications for health care practice and improved policies for victims of sexual violence in the Democratic Republic of Congo. J Int Womens Stud. 2008;10(2):64–72 [Google Scholar]

- 5.The War Within the War: Sexual Violence Against Women and Girls in Eastern Congo. New York, NY: Human Rights Watch; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sexual Violence in the Congo War: A Continuing Crime. New York, NY: Human Rights Watch; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 7.US Dept of State Background note: Democratic Republic of the Congo. Available at: http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/2823.htm. Accessed February 22, 2011

- 8.Figures on Sexual Violence Reported in the DRC in 2008. New York, NY: United Nations; Population Fund; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taback N, Painter R, King B. Sexual violence in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. JAMA. 2008;300(6):653–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Herp M, Rackley E, Parque V, Ford N. Mortality, violence and lack of access to healthcare in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Disasters. 2003;27(2):141–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steiner B, Benner MT, Sondorp E, Schmitz KP, Mesmer U, Rosenberger S. Sexual violence in the protracted conflict of DRC programming for rape survivors in South Kivu. Confl Health. 2009;3:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohambe MCO, Muhigwa JBB, Wa Mamba BM. Women's Bodies as a Battleground: Sexual Violence Against Women and Girls During the War in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Uvira, Democratic Republic of Congo: Réseau des Femmes pour un Développement Associatif; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Longombe AO, Claude KM, Ruminjo J. Fistula and traumatic genital injury from sexual violence in a conflict setting in eastern Congo: case studies. Reprod Health Matters. 2008;16(31):132–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.“Now, the World Is Without Me”: An Investigation of Sexual Violence in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Humanitarian Initiative; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Onsrud M, Sjøveian S, Luhiriri R, Mukwege D. Sexual violence-related fistulas in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;103(3):265–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pham PN, Vinck P, Weinstein HM. Human rights, transitional justice, public health and social reconstruction. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(1):98–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ministry of Planning, Democratic Republic of Congo Demographic and Health Survey 2007. Calverton, MD: Macro International Inc; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Annan J, Brier M. The risk of return: intimate partner violence in northern Uganda's armed conflict. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(1):152–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baaz ME, Stern M. Why do soldiers rape? Masculinity, violence and sexuality in the armed forces in the Congo (DRC). Int Stud Q. 2009;53(2):495–518 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Annuaires Données Sanitaires 2006. Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo: Sécrétariat Général du Ministére de la Santé; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacroPlan Programme Elargi de Vaccinatión (PEV). Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo: Direction d'Etudes et Planificatión; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rutstein S, Johnson K. The DHS Wealth Index. Calverton, MD: ORC Macro; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hynes M, Ward J, Robertson C, Crouse A. A determination of the prevalence of gender-based violence among conflict-affected populations in East Timor. Disasters. 2004;28(3):294–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Survey on Violence Against Women in Rwanda. Kigali, Rwanda: Association of Widows of the April Genocide; 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ward J. If Not Now, When? Addressing Gender-Based Violence in Refugee, Internally Displaced, and Post-Conflict Settings. New York, NY: RHRC Consortium; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ward J, Marsh M. Sexual violence against women and girls in war and its aftermath: realities, responses, and required resources. Paper presented at: International Symposium on Sexual Violence in Conflict and Beyond, June 21–23, 2006, Brussels, Belgium [Google Scholar]

- 27.“You Will Be Punished”: Attacks on Civilians in Eastern Congo. New York, NY: Human Rights Watch; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Notar S. Peacekeepers as perpetrators: sexual exploitation and abuse of women and children in the Democratic Republic of Congo. J Gend Soc Policy Law. 2006;14(2):413–429 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heise L, Ellsberg M, Gottmoeller M. A global overview of gender-based violence. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2002;78(suppl 1):S5–S14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hindin MJ, Kishor S, Ansara DL. Intimate Partner Violence Among Couples in 10 DHS Countries: Predictors and Health Outcomes. Calverton, MD: Macro International Inc; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ackerson LK, Kawachi I, Barbeau EM, Subramanian SV. Effects of individual and proximate educational context on intimate partner violence: a population-based study of women in India. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(3):507–514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hindin MJ, Adair L. Who's at risk? Factors associated with intimate partner violence in the Philippines. Soc Sci Med. 2002;55(8):1385–1399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kishor S, Johnson K. Reproductive health and domestic violence: are the poorest women uniquely disadvantaged? Demography. 2006;43(2):293–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coghlan B, Ngoy P, Mulumba F, et al. Mortality in the Democratic Republic of Congo: An Ongoing Crisis. New York, NY: International Rescue Committee; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wakabi W. Sexual violence increasing in Democratic Republic of Congo. Lancet. 2008;371(9606):15–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ellsberg M, Heise L, Pena R, Agurto S, Winkvist A. Researching domestic violence against women: methodological and ethical considerations. Stud Fam Plann. 2001;32(1):1–1611326453 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jansen HA, Watts C, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Garcia-Moreno C. Interviewer training in the WHO Multi-Country Study on Women's Health and Domestic Violence. Violence Against Women. 2004;10(7):831–849 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clinton demands arrests over DRC sexual violence Mail & Guardian Online. Available at: http://mg.co.za/article/2009-08-12-hillary-clinton-demands-arrests-over-drc-sexual-violence. Accessed February 22, 2011

- 39.Constitution of the Democratic Republic of Congo, Article 15. Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo: Government of the Democratic Republic of Congo; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Horváth E, Zukani M, Eppel D, et al. Gender-based violence laws in sub-Saharan Africa. Available at: http://www.nycbar.org/pdf/report/GBVReportFinal2.pdf. Accessed February 22, 2011

- 41.Kilonzo N, Ndung'u N, Nthamburi N, et al. Sexual violence legislation in sub-Saharan Africa: the need for strengthened medico-legal linkages. Reprod Health Matters. 2009;17(34):10–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilson Park Conference: women targeted or affected by armed conflict—what role for military peacekeepers? Available at: http://www.unifem.org/attachments/events/WiltonParkConference_Presentations_200805.pdf, 2008. Accessed February 22, 2011

- 43.Prendergast J, Atama N. Eastern Congo: An Action Plan to End the World's Deadliest War. Washington, DC: Enough Project; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vinck P, Pham P, Baldo S, Shigekane RA. Living With Fear: A Population-Based Survey on Attitudes About Peace, Justice, and Social Reconstruction in Eastern Congo. Berkeley, CA: University of California; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prendergast J. Congo's enough moment: the case for conflict minerals certification and army reform. Available at: http://www.enoughproject.org/files/publications/congo_enough_moment.pdf. Accessed February 22, 2011