Abstract

Objectives

Human coronary bare metal stents (BMS) and drug-eluting stents (DES) from autopsy cases with implant durations >30 days were examined for the presence of neointimal atherosclerotic disease.

Background

Neointimal atherosclerotic change (neoatherosclerosis) following BMS implantation is rarely reported and usually occurs beyond 5 years. The incidence of neoatherosclerosis following DES implantation has not been reported.

Methods

All available cases from the CVPath stent registry (n=299 autopsies), which includes a total of 406 lesions (197 BMS, 209 DES [103 sirolimus-eluting stents (SES), and 106 paclitaxel-eluting stents (PES)]) with implant duration >30 days were examined. Neoatherosclerosis was recognized as clusters of lipid-laden foamy macrophages within the neointima with or without necrotic core formation.

Results

The incidence of neoatherosclerosis was significantly greater in DES (31%) than BMS (16%) lesions (p<0.001). The median stent duration with neoatherosclerosis was shorter in DES than BMS (DES; 420 [361–683], BMS; 2160 [1800–2880] days, p<0.001). Unstable lesions characterized as thin-cap fibroatheromas or plaque rupture were more frequent in BMS (n=7, 4%) than DES (n=3, 1%) (p=0.17), with relatively shorter implant durations for DES (1.5±0.4 years) compared to BMS (6.1±1.5 years). Independent determinants of neoatherosclerosis identified by multiple logistic regression included younger age (p<0.001), longer implant durations (p<0.001), SES usage (p<0.001), PES usage (p=0.001), and underlying unstable plaques (p=0.004).

Conclusions

Neoatherosclerosis is a frequent finding in DES and occurs earlier than in BMS. Unstable features of neoatherosclerosis are identified for both BMS and DES with shorter implant durations for the latter. The development of neoatherosclerosis may be yet another rare contributing factor to late thrombotic events.

Keywords: drug-eluting stent, bare metal stent, pathology, neoatherosclerosis

Introduction

Percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) involving stenting are the most widely performed procedures for the treatment of symptomatic coronary disease (1). Although first generation sirolimus- (SES; Cypher™, Cordis Corp., Miami Lakes, FL) and paclitaxel- (PES; Taxus™, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA) drug-eluting stents (DES) have radically reduced restenosis (2,3) complications of late (LST) and very late stent thrombosis (VLST) have emerged as an important but small limitation to this technology.

Both clinical imaging and autopsy studies suggest that the primary etiology of LST is the lack of complete endothelialization over stent struts. Interrogation of stented coronary arteries by angioscopy confirms that the incidence of uncovered struts in patients receiving DES is high, 20% at two years (4). However, cause of LST is considered to be multifactorial, and other mechanisms in addition to delayed healing may be important in the pathophysiology of LST.

Although thrombotic event related to atherosclerosis of native coronary vessels is a widely accepted cause of acute coronary syndromes and sudden death (5), there is little data in reference to lesion morphologies that may contribute to thrombosis associated with stents. Chen et al. have reported that a significant number of patients with bare metal stents (BMS) and restenosis present with acute myocardial infarction or unstable angina (6) which raises the question whether these events might be attributable to plaque rupture within the neointima. While we have also reported a case of sudden coronary death caused by plaque rupture secondary to atherosclerotic change developing within the neointima of a BMS (7), this phenomenon is believed to be rare and is thought to occur with extended implant durations beyond 5 years (8). The incidence of atherosclerosis occurring within DES and BMS implants at autopsy has not been examined systematically. The present investigation represents a histopathological study of atherosclerosis occurring within BMS and DES implants focused on the incidence, character, and its temporal development, in particular as an underlying cause for acute coronary thrombosis.

Methods

Patients and Lesions

All available material from the CVPath stent registry, which includes 299 consecutive autopsy cases (142 BMS, 157 DES [81 SES, and 76 PES] patients) with 406 lesions of > 30 days implant duration (197 BMS, 209 DES [103 SES, and 106 PES] lesions) was reviewed. Hearts with multiple stents, overlapping and consecutively implanted stents were treated as one lesion, while stents including a gap of more than 5mm were treated as separate lesions, as previously described (9). The cause of death was reported as stent related death (thrombosis and restenosis), diffuse coronary artery disease (CAD) with restenosis, non-stent related cardiac death, and non-cardiac death as previously defined (9). All available clinical records were reviewed for the duration of implant, risk factors, and mechanism of death.

Histologic Preparation

Hearts with stented arteries were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, dissected off the heart, radiographed, and submitted for plastic embedding in methylmethacrylate. Coronary arteries were segmented at 2–3mm intervals and histologic sections were cut at 6μm and stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) and Movat pentachrome as previously described (9).

Pathologic Assessment

Acute thrombosis was defined as a platelet-rich thrombus occupying > 30% of the cross-sectional area of the lumen while stent restenosis was defined as > 75% cross sectional area narrowing by neointimal formation. The native plaques (outside stent struts) were assessed and classified using our modified AHA classification, to include traditional definitions of pathological intimal thickening, fibroatheroma, thin-cap fibroatheroma, and plaque rupture. Fibrotic lesions with or without calcification that did not show macrophage infiltration were noted separately (5). Atherosclerosis of the neointima within the stent was defined as peri-strut foamy macrophage clusters with or without calcification, fibroatheromas, thin-cap fibroatheromas, and ruptures with thrombosis. In all cases there was no communication of the lesion within the stent with the underlying native atherosclerotic plaque.

Immunohistochemistry for the identification of macrophages was carried out in selected cases using a CD68 antibody (dilution 1:800, Dako Carpinteria, CA) as previously described (10). The primary antibody was labeled using an LSAB kit (Dako) and positive staining visualized by a 3-amino-9ethyl carbazole (AEC) substrate-chromogen system with Gill’s hematoxylin as a counterstain.

The data was analyzed on the basis of lesions and not by patients as often times the duration of multiple stents varies as patients undergo repeat PCI dictated by the onset of symptoms. The development of atherosclerotic change by duration of stent implantation was also assessed in addition to the regional placement of the stent.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables with normal distribution were expressed as mean ± SD. Variables with non-normal distribution were expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR). Comparisons of continuous variables with normal distribution were tested by Student t test. A Wilcoxon rank sum test was used for comparisons of non-normally distributed continuous variables. Categorical variables were compared using chi-square test. Normality of distribution was tested with the Wilk-Shapiro test. Multiple logistic generalized estimating equations (GEE) modeling (9) was performed to identify the determinants of stent neoatherosclerosis, in which age, gender, and significant variables (p<0.05) among lesion characteristics (the number of stents, stent duration, indication of stent implantation, lesion location, stent length, overlapping stents, underlying plaque morphology, and stent type) in univariate analysis were entered as independent variables. GEE modeling was necessary because of the clustered nature of more than 1 stented lesions in some cases- resulting in unknown correlations among measurements within lesion clusters. A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient Characteristics (Table 1)

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| BMS (142 patients) | DES

|

P value BMS vs. DES (SES + PES) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (SES + PES) (157 patients) | SES (81 patients) | PES (76 patients) | |||

| Age, yrs | 62 ± 14 | 60 ± 12 | 60 ± 12 | 59 ± 12 | 0.143 |

| Male gender | 105 (74) | 117 (75) | 59 (73) | 58 (76) | 0.909 |

| Hypertension | 67/94 (71) | 90/114 (79) | 41/56 (73) | 49/58 (84) | 0.215 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 41/94 (44) | 35/115 (30) | 14/57 (25) | 21/58 (36) | 0.060 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 50/94 (53) | 73/114 (64) | 34/56 (61) | 39/58 (67) | 0.140 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 85/128 (66) | 66/133 (50) | 31/67 (46) | 35/66 (53) | 0.009 |

| Prior CABG | 32/139 (23) | 18/146 (12) | 10/76 (13) | 8/70 (11) | 0.008 |

| Number of stent per patient | 1.4 ± 1.0 | 1.6 ± 1.1 | 1.6 ± 1.1 | 1.7 ± 1.1 | 0.062 |

| Cause of death | |||||

| Stent related | |||||

| Thrombosis | 5* (4) | 32† (20) | 14 (17) | 18 (24) | <0.001 |

| Restenosis without diffuse CAD | 19 (13) | 5 (3) | 2 (2) | 3 (4) | 0.001 |

| Diffuse CAD with restenosis | 20 (14) | 4 (3) | 3 (4) | 1 (1) | <0.001 |

| Non-stent related cardiac | 46 (32) | 60 (38) | 32 (40) | 28 (37) | 0.293 |

| Non-cardiac | 46 (33) | 46 (29) | 25 (31) | 21 (28) | 0.563 |

| Unknown | 6 (4) | 10 (6) | 5 (6) | 5 (7) | 0.411 |

Values are expressed as means ± SD or n (%).

Among 5 patients with thrombosis in BMS group, 4 patients had neointimal plaque rupture and 1 patient had restenosis only.

Among 32 patients with thrombosis in DES group, 1 patient had neointimal plaque rupture, 2 patients had restenosis, and the rest had uncovered struts from varying etiologies.

BMS = bare metal stents, CABG = coronary artery bypass graft, CAD = coronary artery disease, DES = drug-eluting stents, PES = paclitaxel-eluting stents, SES = sirolimus-eluting stents

Age, sex, and coronary risk factors were similar for patients receiving BMS, or DES. Patients receiving BMS had a higher prevalence of prior history of myocardial infarction (p=0.009) and coronary artery bypass grafts (p=0.008) than those receiving DES. On the other hand, stent related deaths from thrombosis were significantly more frequent in DES than BMS (20% vs. 4%, p<0.001). While in-stent restenosis as a cause of death was more frequent in BMS than DES (BMS, n=40 [28%]; and DES, n=11 [7%], p<0.001), however, the incidence of non-stent related and non-cardiac death were similar between groups.

Lesion Characteristics (Table 2)

Table 2.

Lesion Characteristics

| BMS (197 lesions) | DES

|

P value BMS vs. DES (SES + PES) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (SES + PES) (209 lesions) | SES (103 lesions) | PES (106 lesions) | |||

| Stent duration, days | 721 (271, 1801) | 361 (172, 540) | 361 (180, 541) | 270 (149, 473) | <0.001 |

| Indication of stent implantation | |||||

| Stable angina pectoris | 150 (76) | 150 (72) | 72 (70) | 78 (74) | 0.316 |

| Unstable angina pectoris/AMI | 47 (24) | 59 (28) | 31 (30) | 28 (26) | |

| Lesion location | |||||

| Vessel: Left main coronary artery | 4 (2) | 6 (3) | 2 (2) | 4 (4) | 0.501 |

| Left anterior descending | 73 (37) | 87 (42) | 41 (40) | 46 (43) | |

| Left circumflex | 45 (23) | 51 (24) | 24 (23) | 27 (26) | |

| Right coronary artery | 75 (38) | 65 (31) | 36 (35) | 29 (27) | |

| Proximal lesion | 77/161 (48) | 102/202 (51) | 45/98 (46) | 57/104 (55) | 0.613 |

| Mid/Distal lesion | 84/161 (52) | 100/202 (49) | 53/98 (54) | 47/104 (45) | |

| Stent length, mm | 16.0 (12.0, 24.0) | 22.0 (15.5, 30.0) | 21.0 (15.0, 30.0) | 22.0 (15.8, 30.3) | <0.001 |

| Overlapping stents | 36 (18) | 63 (30) | 30 (29) | 33 (31) | 0.005 |

| Underlying plaque morphology | |||||

| Ruptured plaque/TCFA | 26 (13) | 49 (23) | 28 (27) | 21 (20) | 0.008 |

| Fibroatheroma | 86 (44) | 104 (50) | 44 (43) | 60 (57) | 0.261 |

| Fibrocalcific | 29 (15) | 16 (7) | 8 (8) | 8 (7) | 0.023 |

| Pathologic intimal thickening | 47 (24) | 20 (10) | 13 (12) | 7 (7) | <0.001 |

| Others* | 9 (4) | 20 (10) | 10 (10) | 10 (9) | 0.051 |

Values are expressed as medians (interquartile range) or n (%).

“Others” includes underlying restenotic lesion, calcified nodule, and dissection.

AMI = acute myocardial infarction, BMS = bare metal stents, DES = drug-eluting stents, PES = paclitaxel-eluting stents, SES = sirolimus-eluting stents, TCFA = thin-cap fibroatheroma

The median stent implant duration was shorter in lesions treated with DES versus BMS (DES; median 361 [IQR 172, 540], BMS; 721 [271, 1801] days, p<0.001). The shortest stent duration was 35 days for both SES and PES, and 31 days in BMS, whereas the longest stent duration was 1800 days in SES, 1814 days in PES, and 7201 days in BMS. Indications for stent implantation and lesion location were comparable between groups. Stent lengths were significantly longer in DES than BMS (DES; 22.0 [15.5, 30.0], BMS; 16.0 [12.0, 24.0] mm, p<0.001). The prevalence of overlapping stents was also significantly higher in DES (DES; 30%, BMS; 18%, p=0.005). Notably, the underlying plaque morphology was different with unstable lesions (i.e. ruptured plaques and thin-cap fibroatheroma) more commonly found in DES as compared to BMS (p=0.008). On the other hand, fibrocalcific and pathologic intimal thickening were significantly more frequent in BMS than DES; p=0.023, and p<0.001, respectively).

The Incidence of Neoatherosclerosis (Tables 3, 4, and 5)

Table 3.

Incidence of Neoatherosclerosis Stratified by the Duration of Implant

| BMS (197 lesions) | DES

|

P value BMS vs. DES (SES + PES) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (SES + PES) (209 lesions) | SES (103 lesions) | PES (106 lesions) | |||

| Duration with any neoatherosclerosis, days | 2160 (1800, 2880) | 420 (361, 683) | 450 (361, 660) | 383 (270, 721) | <0.001 |

| Incidence of any neoatherosclerosis | |||||

| ≤ 2 years | 0/88 (0) | 51/177 (29) | 32/87 (37) | 19/90 (21)* | <0.001 |

| > 2 years, ≤ 6 years | 17/76 (22) | 13/32 (41) | 7/16 (44) | 6/16 (38) | 0.053 |

| > 6 years | 14/33 (42) | - | - | - | - |

| All | 31/197 (16) | 64/209 (31) | 39/103 (38) | 25/106 (24)† | <0.001 |

| Incidence of foamy macrophage clusters | |||||

| ≤ 2 years | 0/88 (0) | 25/177 (14) | 10/87 (12) | 15/90 (17) | <0.001 |

| > 2 years, ≤ 6 years | 2/76 (3) | 6/32 (19) | 4/16 (25) | 2/16 (13) | 0.004 |

| > 6 years | 3/33 (9) | - | - | - | - |

| All | 5/197 (3) | 31/209 (15) | 14/103 (14) | 17/106 (16) | <0.001 |

| Incidence of fibroatheromas | |||||

| ≤ 2 years | 0/88 (0) | 23/177 (13) | 19/87 (22) | 4/90 (4)‡ | <0.001 |

| > 2 years, ≤ 6 years | 11/76 (15) | 7/32 (22) | 3/16 (19) | 4/16 (25) | 0.346 |

| > 6 years | 8/33 (24) | - | - | - | - |

| All | 19/197 (10) | 30/209 (14) | 22/103 (21) | 8/106 (8)§ | 0.145 |

| Incidence of TCFA/plaque rupture | |||||

| ≤ 2 years | 0/88 (0) | 3/177 (2) | 3/87 (4) | 0/90 (0) | 0.219 |

| > 2 years, ≤ 6 years | 4/76 (5) | 0/32 (0) | 0/16 (0) | 0/16 (0) | 0.186 |

| > 6 years | 3/33 (9) | - | - | - | - |

| All | 7/197 (4) | 3/209 (1) | 3/103 (3) | 0/106 (0) | 0.169 |

| Calcified neointima | 9 (5) | 11 (5) | 7 (7) | 4 (4) | 0.747 |

| Location of neoatherosclerosis | |||||

| Proximal lesion | 21/77 (27)|| | 34/102 (33)|| | 19/45 (42) | 15/57 (26) | 0.384 |

| Mid/Distal lesion | 10/84 (12) | 30/100 (30) | 20/53 (37) | 10/47 (21) | 0.003 |

Values are expressed as medians (interquartile range) or n (%).

p=0.021 vs. SES group,

p=0.025 vs. SES group,

p<0.001 vs. SES group, and

p=0.004 vs. SES group.

Incidence of atherosclerotic change in proximal lesion was higher than those in mid/distal lesion in BMS group (27% vs. 12%, p=0.014), but not in DES group (33% vs. 30%, p=0.611).

BMS = bare metal stents, DES = drug-eluting stents, PES = paclitaxel-eluting stents, SES = sirolimus-eluting stents, TCFA = thin-cap fibroatheroma

Table 4.

Ten Patients with Thin-cap Fibroatheroma or Plaque Rupture within Neointima Following Stent Implantation

| Case | Age, Sex |

Stent type | Location | Number of stent |

Stent length, mm |

Indication for implantation |

Duration of implant, months |

Cause of death |

Representative images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thin-cap fibroatheroma | |||||||||

| 1 | 58 M |

BMS (NIR) | LAD prox | 1 | 18 | SAP | 61 | Non-cardiac |

|

| 2 | 63 M |

BMS (MULTI-LINK) | RCA mid | 1 | 18 | SAP | 98 | Non-stent related cardiac |

|

| 3 | 73 M |

BMS (Bx VELOCITY) | RI prox | 1 | 16 | SAP | 50 | Non-cardiac |

|

| 4 | 40 F |

DES (SES) | RCA prox | 1 | 23 | AMI | 17 | Stent related (thrombosis) |

|

| 5 | 67 M |

DES (SES) | RCA prox | 1 | 13 | SAP | 13 | Non-stent related cardiac |

|

| Plaque rupture | |||||||||

| 6 | 43 M |

BMS (MINI-CROWN) | LAD prox | 1 | 14 | SAP | 84 | Stent related (thrombosis) |

|

| 7 | 87 F |

BMS (2 AVE) | RCA prox | 2 | 60 | SAP | 61 | Stent related (thrombosis) |

|

| 8 | 47 M |

BMS (3 Gianturco-Roubin II) | RCA prox | 3 | 90 | SAP | 96 | Stent related (thrombosis) |

|

| 9 | 43 M |

BMS (5 MULTI-LINK ZETA) | RCA prox-dist | 5 | 70 | SAP | 61 | Stent related (thrombosis) |

|

| 10 | 59 M |

DES (SES) | RCA dist | 1 | 23 | AMI | 23 | Stent related (thrombosis) |

|

AMI = acute myocardial infarction, BMS = bare metal stents, DES = drug-eluting stents, LAD = left anterior descending artery, RCA = right coronary artery, RI = ramus intermedius, SAP = stable angina pectoris, SES = sirolimus-eluting stents

Table 5.

Independent Risk Factors for Neoatherosclerosis

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (per year) | 0.963 | 0.942 – 0.983 | <0.001 |

| Stent duration (per month) | 1.028 | 1.017 – 1.041 | <0.001 |

| SES usage | 6.534 | 3.387 – 12.591 | <0.001 |

| PES usage | 3.200 | 1.584 – 6.469 | 0.001 |

| Underlying unstable lesion* | 2.387 | 1.326 – 4.302 | 0.004 |

“Underlying unstable lesion” includes ruptured plaque and thin-cap fibroatheroma.

CI = confidence interval, OR = odds ratio, PES = paclitaxel-eluting stents, SES = sirolimus-eluting stents

Representative images of newly formed atherosclerotic changes within the neointima in various stents are shown in Figure 1. Notably, 85% (177 lesions) DES were implanted for 2 years or less with no lesions extending beyond 6 years, while 45% (88 lesions) BMS were implanted for 2 years or less and 17% (33 lesions) had durations of more than 6 years (Table 3). The incidence of any neoatherosclerosis was greater in DES (n=64, 31%) than BMS (n=31, 16%) lesions (p<0.001). Nearly half the DES lesions with neoatherosclerosis (31 of 64 lesions, 48%) contained peri-strut foamy macrophage clusters and the other half showed fibroatheromas. A significant temporal relationship was found among BMS and DES; atherosclerotic change occurred in significantly shorter implant durations for DES than BMS (DES; 420[361,683], BMS; 2160 [1800, 2880] days, p<0.001) (Table 3). The earliest implant duration showing early atherosclerotic change characterized by foamy macrophage clusters was observed at 70 and 120 days for PES and SES, respectively while its occurrence in BMS was found much later at 900 days. Similarly, the earliest implant durations for lesions with necrotic cores were relatively short in DES; at 270 and 360 days for SES and PES, whereas the earliest duration for necrotic core formation in BMS was longer, 900 days. Representative images of fibroatheroma with necrotic core from a PES implant of 14 months duration is illustrated in Figure 2A, B, C. The cumulative incidence of any neoatherosclerotic change relative to implant duration is shown in Figure 3 and is significantly higher in DES as compared to BMS. Notably, the incidence of neoatherosclerosis in BMS does not catch up to DES despite the longer durations of stent implantation beyond 6 years.

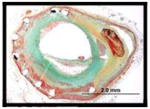

Figure 1. Representative images of the various stages of newly formed atherosclerotic changes within the neointima after stent implantation are illustrated.

Foamy macrophage clusters in the peri-strut region of sirolimus-eluting stents (SES) implanted for13 months antemortem is seen in A. Fibroatheroma with foamy macrophage rich lesion and early necrotic core formation in SES of 13 months duration (B). Fibroatheroma with peri-strut early necrotic core, cholesterol clefts, surface foamy macrophages, and early calcification (arrow) in SES at 13 months (C). Peri-strut late necrotic core in the neointima characterized by large aggregate of cholesterol cleft in SES at 17 months (D). Fibroatheroma with calcification in the necrotic core in SES of 10 months duration (E). A peri-strut calcification (arrow) with fibrin in SES of 7 months duration (F). (G and H) A low (H) and high power (G) magnification image of a severely narrowed bare metal stents (BMS) implanted 61 months with a thin-cap fibroatheroma. Note macrophage infiltration and a discontinuous thin fibrous cap (G). (I and J) A low magnification image shows a plaque rupture with an acute thrombus that has totally occluded the lumen in BMS implanted for 61 months antemortem (I). A high magnification image shows a discontinuous thin-cap with occlusive luminal thrombus (J).

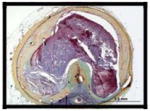

Figure 2. Representative cases showing atherosclerotic change following BMS, SES, and PES implantation.

(A to C) Histologic sections from a 65-year-old woman with a paclitaxel-eluting stent (PES) implanted in the left circumflex artery 14 months antemortem, who died of traumatic brain injury. A low power image shows a patent lumen with moderate neointimal growth (A), foamy macrophage infiltration and necrotic core formation with cholesterol clefts is seen at high magnification in B. (C) Same section as B showing CD68 positive macrophages in the neointima. (D to F) Histological sections from a 59-year-old male with sirolimus-eluting stents (SES) (Patient 10 in Table 4) implanted for 23 months who died from stent thrombosis (D). Note thin-cap fibroatheroma with fibrous cap disruption in E (arrows) from boxed area in D. The thrombus (Th) was more apparent in the distal section taken 3 mm apart (D). F shows CD 68 positive macrophages in the fibrous cap and in the underlying necrotic core. (G to I) Histologic section from a 47-year-old male who had a bare metal stents (BMS) implanted 8 years prior to death (Case 8 in Table 4). Note occlusive thrombus (Th) in the lumen and ruptured plaque (boxed area in G), which is shown at higher magnification in H with large number of macrophages within the lumen as well as at the ruptured cap. Note large number of CD 68 positive macrophages at the site of rupture (I).

Figure 3. Bar graph showing cumulative incidence of atherosclerotic change with time following implantation of BMS vs. SES, and PES.

Both sirolimus-eluting stents (SES) and paclitaxel-eluting stents (PES) show earlier onset of neoatherosclerosis and a higher incidence of lesion formation as compared to bare metal stents (BMS). No drug-eluting stents (DES) was available beyond 6 years.

The incidence of neoatherosclerosis was also evaluated based on the implant duration (Table 3). For those implants 2 years or less, the DES group had a greater incidence of any neoatherosclerosis (DES= 29% vs. BMS= 0%, p<0.001), which was represented by a greater incidence of foamy macrophage clusters (DES= 14% vs. BMS= 0%, p<0.001) as well as fibroatheromas (DES= 13% vs. BMS= 0%, p<0.001). For durations between 2 and 6 years, the DES group still expressed a higher incidence of neoatherosclerosis (DES= 41% vs. BMS= 22%, p=0.053) (Table 3). The incidence of any neoatherosclerotic change was greater in SES than PES for implant durations of 2 years or less (SES= 37% vs. PES= 21%, p=0.021), although differences did not remain with stents implanted for 2 to 6 years (SES= 44% vs. PES= 38%, p=0.719).

In regards to the location of stent and development of atherosclerosis, the incidence of atherosclerotic change in proximal lesion was significantly higher than those in mid/distal lesion in BMS (27% vs. 12%, p=0.014) however, this difference was not seen in DES (33% vs. 30%, p=0.611) (Table 3).

More advanced lesions – unstable plaque, i.e., thin-cap fibroatheroma and ruptured plaques with thrombosis (Figure 2D to I) were seen for both BMS (n=7, 4%) and DES (n=3, 1%), where the majority of BMS were > 5 years (average implant duration 6.1±1.5 years) while for DES, unstable neoatherosclerotic lesions were identified with devices implanted ≤ 2 years (1.1, 1.4, and 1.9 years). Details of the 10 patients (7 BMS and 3 DES) with thin-cap fibroatheroma or plaque rupture within the in-stent neointima are provided in the visual Table 4.

The incidence of neoatherosclerosis did not differ between patients with stent related death and those with non-stent related death both in BMS (18% vs. 20%, p=0.848) and in DES (27% vs. 42%, p=0.099). In patients with stent-related death, the incidence of neoatherosclerosis was comparable between BMS and DES (18% vs. 27%, p=0.339), whereas in patients with non-stent-related death, DES had a higher incidence of neoatherosclerosis than BMS (42% vs. 20%, p<0.001).

A multiple logistic GEE modeling identified younger age (odds ratio [OR] 0.963, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.942 – 0.983; p<0.001), longer implant duration (OR 1.028, 95% CI 1.017 – 1.041; p<0.001), SES usage (OR 6.534, 95% CI 3.387 – 12.591; p<0.001), PES usage (OR 3.200, 95% CI 1.584 – 6.469; p=0.001), and underlying unstable plaque (OR 2.387, 95% CI 1.326 – 4.302; p=0.004) as independent risk factors for neoatherosclerosis (Table 5).

Discussion

The present study suggests that in-stent neoatherosclerosis occurs in both BMS and DES however for DES implants it is observed more frequently and at an earlier time point (median = 420 days) as compared to BMS (median = 2160 days). For stent related deaths, in-stent neoatherosclerosis incidence was similar in BMS and DES (18% vs. 20%). However, for non-stent related death the incidence of neoatherosclerosis was more frequent in DES than BMS (42% vs. 20%, p<0.001). Moreover, neoatherosclerosis in DES show unstable characteristics by 2 years following implant, while similar features in BMS occur at relatively later time points (average implant duration 6 years). These observations raise the question whether neoatherosclerosis seen within DES as well as BMS at follow-up, may in part be responsible for some late thrombotic events. The implications of current findings may be of practical importance since the usage of DES implants continues to increase worldwide. The occurrence of uncovered struts complicated by a dysfunctional endothelium remains the primary cause of LST in DES nevertheless the present study adds another risk factor, i.e., in-stent plaque rupture, although a rare event.

While the underlying processes responsible for the development of neoatherosclerosis following stent implantation are likely multifactorial, we hypothesize that it may involve the inability to maintain a fully functional endothelialized luminal surface within the stented segment (11). The endothelium normally provides an efficient barrier against the excessive uptake of circulating lipid and this may no longer be true in the in-stent regions of DES and BMS (12). In the present study, BMS exhibited greater trends for neoatherosclerotic changes occurring in the more proximal than distal lesions relative to DES. Thus indicating divergent mechanisms where neoatherosclerosis attributed to DES may be more related to incompetent and incomplete endothelialization as opposed to shear stress for BMS. These findings in the BMS may be more akin to the development of atherosclerosis in native coronary which is most prominent in the proximal regions of the coronary arteries (13).

Recently, chronic endoplasmic reticular stress in endothelial cells at athero-susceptible sites with arterial flow disturbances has been linked to inflammation (14). Shear-induced changes in endothelial phenotype (collectively known as mechanotransduction) may promote the expression of transmembrane proteins, like integrins and platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1), which further allows inflammatory-cell attachment and migration to subendothelial spaces (13). Changes in endothelial cell permeability could presumably allow greater amounts of lipoproteins to enter the subendothelial space with an affinity for matrix proteins, in particular proteoglycans that promote their retention (15).

The relatively faster development of neoatherosclerosis in DES vs. BMS is probably related to drug effects, which are also responsible for incomplete endothelialization. Previous animal studies of DES (11) suggest that the regenerating endothelial lining could be incompetent and therefore may result in activation of endothelial cells which leads to monocyte adherence with subsequent sub-endothelial migration. Incomplete (delayed) endothelial regrowth and recovery observed with SES or PES that may contribute to atherogenesis is characterized by poor cell-to-cell contacts identified by decreased expression of PECAM-1 and anti-thrombotic mediators such as thrombomodulin (11).

Experimental evidence suggests that neoatherosclerosis within stents can be associated with delayed arterial healing compounded by lethal injury to smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells. We have reported 32P β-emitting stent implanted with activities ranging from 6 μCi to 48 μCi showed focal evidence of atherosclerotic change in normal arteries of New Zealand White rabbits examined at 6- and 12- months (16). Considering it is well known that normal arteries of the rabbit do not develop atherosclerosis in the absence of hypercholesterolemia, these results suggest that the atherogenic process is inherent to process occurring within the stent itself.

In humans, two pathologic studies have reported neoatherosclerotic change occurring in vein graft and in native coronary arteries with foam cell infiltration following BMS implants (17,18). Previous clinical studies have also suggested endothelial dysfunction following SES implantation by showing impaired vasomotor function in the adjacent segment of stents (19), though the precise mechanism for the endothelial dysfunction in the stented segment in humans remains unknown.

Clinical Relevance

Coronary SES implants in 57 patients recently interrogated by angioscopy showed a 35% increase in the maximum yellow color of the neointima within 10 months of follow-up (20). Even among lesions that did not express yellow plaque at baseline, yellow color was detected in 95% of SES implants, suggesting a neoatherosclerotic change in response to the stent.

A retrospective analysis of 4,503 patients with at least 1 BMS implant reported by Doyle et al. (21) showed that the incidence of stent thrombosis was 0.8% at 1 year, and 2% at 10 years, which is lower than reported for DES (SES+PES) 2.9% at 3 years involving an all comer registry of 8,146 patients (22). In contrast, a meta-analysis of 18,023 patients reported by Stettler et al. (23) revealed that mortality risks were similar between BMS and DES (SES+PES), although several trials included in the meta-analysis evaluated only cardiac and not all cause mortality. The largest registry (SCAAR) reported by Lagerqvist et al. (24) involved 73,798 stents from 42, 150 patients with DES and BMS showed a biphasic incidence of LST with higher rates in the first year in BMS followed by a higher rate in DES from 1 to 3 years, for unadjusted cumulative probability of acute occlusion. However, following adjustment for background and procedure characteristics no differences were observed at 3 years. As compared to large clinical trials, our study shows apparently higher rates of stent thrombosis, probably because the population may be biased towards individuals dying from DES complication (all comers without adjustment). In addition, our population is non-randomized, and unknown confounders could exist even after adjustment by multivariate GEE modeling. Despite these shortcomings, to our knowledge, the present study represents the first report demonstrating the incidence and type of neoatherosclerosis within DES and BMS from a large series of stents implanted in native human coronary arteries. Since only histologic studies can provide sufficient detail to accurately characterize neoatherosclerosis within stents, our results offer important insights into late cardiac events attributed to stents.

Conclusion

The current pathologic study suggests that neoatherosclerosis is a frequent finding in DES, and occurs significantly earlier in DES as compared to BMS, however complications are more frequent in BMS than DES and are likely due to longer implant duration. These observations suggest that neoatherosclerosis could be accelerated in DES, and in rare cases contribute to very late thrombotic events in both BMS and DES.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Virmani receives research support from Medtronic AVE, Abbott Vascular, Atrium Medical, OrbusNeich Medical, Terumo Corporation, Cordis Corporation, BioSensors International, Biotronik, and Alchimedics; and is a consultant for Medtronic AVE, Abbott Vascular, W.L. Gore, Atrium Medical, and Lutonix.

Dr. Finn is supported by the NIH grant HL096970-01A1, the Carlyle Fraser Heart Center at Emory University, sponsored research agreement with Medtronic and St. Jude Medical, and is a consultant for Abbott Vascular and Cordis.

CVPath Institute, Gaithersburg, MD 20878 USA provided full support for this work.

Abbreviations

- BMS

bare metal stents

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- CI

confidence interval

- DES

drug-eluting stents

- LST

late stent thrombosis

- OR

odds ratio

- PCI

percutaneous coronary interventions

- PES

paclitaxel-eluting stents

- SES

sirolimus-eluting stents

- VLST

very late stent thrombosis

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Serruys PW, de Jaegere P, Kiemeneij F, et al. A comparison of balloon-expandable-stent implantation with balloon angioplasty in patients with coronary artery disease. Benestent Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:489–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199408253310801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morice MC, Serruys PW, Sousa JE, et al. A randomized comparison of a sirolimus-eluting stent with a standard stent for coronary revascularization. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1773–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moses JW, Leon MB, Popma JJ, et al. Sirolimus-eluting stents versus standard stents in patients with stenosis in a native coronary artery. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1315–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takano M, Yamamoto M, Xie Y, et al. Serial long-term evaluation of neointimal stent coverage and thrombus after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation by use of coronary angioscopy. Heart. 2007;93:1353–6. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.132555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Virmani R, Kolodgie FD, Burke AP, Farb A, Schwartz SM. Lessons from sudden coronary death: a comprehensive morphological classification scheme for atherosclerotic lesions. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:1262–75. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.5.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen MS, John JM, Chew DP, Lee DS, Ellis SG, Bhatt DL. Bare metal stent restenosis is not a benign clinical entity. Am Heart J. 2006;151:1260–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramcharitar S, Garcia-Garcia HM, Nakazawa G, et al. Ultrasonic and pathological evidence of a neo-intimal plaque rupture in patients with bare metal stents. EuroIntervention. 2007;3:290–1. doi: 10.4244/eijv3i2a51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takano M, Yamamoto M, Inami S, et al. Appearance of lipid-laden intima and neovascularization after implantation of bare-metal stents extended late-phase observation by intracoronary optical coherence tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;55:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finn AV, Joner M, Nakazawa G, et al. Pathological correlates of late drug-eluting stent thrombosis: strut coverage as a marker of endothelialization. Circulation. 2007;115:2435–41. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.693739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Virmani R, Guagliumi G, Farb A, et al. Localized hypersensitivity and late coronary thrombosis secondary to a sirolimus-eluting stent: should we be cautious? Circulation. 2004;109:701–5. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000116202.41966.D4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joner M, Nakazawa G, Finn AV, et al. Endothelial cell recovery between comparator polymer-based drug-eluting stents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:333–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ross R. Atherosclerosis--an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:115–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davies PF. Hemodynamic shear stress and the endothelium in cardiovascular pathophysiology. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2009;6:16–26. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Civelek M, Manduchi E, Riley RJ, Stoeckert CJ, Jr, Davies PF. Chronic endoplasmic reticulum stress activates unfolded protein response in arterial endothelium in regions of susceptibility to atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2009;105:453–61. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.203711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skalen K, Gustafsson M, Rydberg EK, et al. Subendothelial retention of atherogenic lipoproteins in early atherosclerosis. Nature. 2002;417:750–4. doi: 10.1038/nature00804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farb A, Shroff S, John M, Sweet W, Virmani R. Late arterial responses (6 and 12 months) after (32)P beta-emitting stent placement: sustained intimal suppression with incomplete healing. Circulation. 2001;103:1912–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.14.1912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Beusekom HM, van der Giessen WJ, van Suylen R, Bos E, Bosman FT, Serruys PW. Histology after stenting of human saphenous vein bypass grafts: observations from surgically excised grafts 3 to 320 days after stent implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;21:45–54. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90715-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inoue K, Abe K, Ando K, et al. Pathological analyses of long-term intracoronary Palmaz-Schatz stenting; Is its efficacy permanent? Cardiovasc Pathol. 2004;13:109–15. doi: 10.1016/S1054-8807(03)00132-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Togni M, Windecker S, Cocchia R, et al. Sirolimus-eluting stents associated with paradoxic coronary vasoconstriction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:231–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.01.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higo T, Ueda Y, Oyabu J, et al. Atherosclerotic and thrombogenic neointima formed over sirolimus drug-eluting stent: an angioscopic study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2:616–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doyle B, Rihal CS, O’Sullivan CJ, et al. Outcomes of stent thrombosis and restenosis during extended follow-up of patients treated with bare-metal coronary stents. Circulation. 2007;116:2391–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.707331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daemen J, Wenaweser P, Tsuchida K, et al. Early and late coronary stent thrombosis of sirolimus-eluting and paclitaxel-eluting stents in routine clinical practice: data from a large two-institutional cohort study. Lancet. 2007;369:667–78. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60314-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stettler C, Wandel S, Allemann S, et al. Outcomes associated with drug-eluting and bare-metal stents: a collaborative network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2007;370:937–48. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61444-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lagerqvist B, Carlsson J, Frobert O, et al. Stent thrombosis in Sweden: a report from the Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:401–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.108.844985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]