Abstract

GPIHBP1, a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein of capillary endothelial cells, shuttles lipoprotein lipase (LPL) from subendothelial spaces to the capillary lumen. An absence of GPIHBP1 prevents the entry of LPL into capillaries, blocking LPL-mediated triglyceride hydrolysis and leading to markedly elevated triglyceride levels in the plasma (i.e., chylomicronemia). Earlier studies have established that chylomicronemia can be caused by LPL mutations that interfere with catalytic activity. We hypothesized that some cases of chylomicronemia might be caused by LPL mutations that interfere with LPL's ability to bind to GPIHBP1. Any such mutation would provide insights into LPL sequences required for GPIHBP1 binding. Here, we report that two LPL missense mutations initially identified in patients with chylomicronemia, C418Y and E421K, abolish LPL's ability to bind to GPIHBP1 without interfering with LPL catalytic activity or binding to heparin. Both mutations abolish LPL transport across endothelial cells by GPIHBP1. These findings suggest that sequences downstream from LPL's principal heparin-binding domain (amino acids 403–407) are important for GPIHBP1 binding. In support of this idea, a chicken LPL (cLPL)–specific monoclonal antibody, xCAL 1–11 (epitope, cLPL amino acids 416–435), blocks cLPL binding to GPIHBP1 but not to heparin. Also, changing cLPL residues 421 to 425, 426 to 430, and 431 to 435 to alanine blocks cLPL binding to GPIHBP1 without inhibiting catalytic activity. Together, these data define a mechanism by which LPL mutations could elicit disease and provide insights into LPL sequences required for binding to GPIHBP1.

Keywords: chylomicron, lipid metabolism, hypertriglyceridemia

Lipoprotein lipase (LPL) is a homodimeric enzyme required for the lipolytic processing of triglycerid-rich lipoproteins (chylomicrons and very low density lipoproteins) (1–3). More than 50 years ago, Havel and Gordon (4) showed that a deficiency of LPL causes severe hypertriglyceridemia (i.e., chylomicronemia). After the cDNA for LPL was cloned, many LPL mutations causing chylomicronemia were identified (1, 5, 6), the majority of which were missense mutations in the aminoterminal catalytic domain. Some mutations abolished catalytic activity, whereas others blocked LPL secretion or interfered with the formation of stable homodimers. In a few instances, the importance and functional relevance of some mutations identified in patients with severe chylomicronemia has remained mysterious. For example, two LPL missense mutations, C418Y and E421K, were identified in patients with severe chylomicronemia (7, 8) but are located in the carboxyl terminus of LPL, distant from the aminoterminal catalytic domain and downstream from carboxyl-terminal sequences implicated in binding lipid substrates (9). (A more detailed description of the findings of the earlier publications is found in the SI Text.) The C418Y and E421K mutations were mysterious because neither mutation had significant effects on catalytic activity (7, 8).

To hydrolyze the triglycerides within plasma lipoproteins, LPL must be located inside capillaries. LPL is synthesized by myocytes and adipocytes and secreted into the interstitial spaces, but is then transported to the capillary lumen by GPIHBP1, a GPI-anchored protein of endothelial cells (10, 11). An absence of GPIHBP1 abolishes the entry of LPL into capillaries, causing severe chylomicronemia and an accumulation of catalytically active LPL in the interstitial spaces (11).

GPIHBP1 missense mutations were recently shown to cause chylomicronemia in humans (12–14). In each case, these mutations abolished GPIHBP1’s capacity to bind LPL. In the current study, we postulated the existence of a complementary class of mutations: LPL missense mutations that would prevent binding to GPIHBP1. Here, we identified two such LPL mutations, thereby uncovering a potential mechanism for chylomicronemia and gaining insights into LPL sequences required for binding GPIHBP1.

Results

We hypothesized that a pair of missense mutations first identified in patients with severe chylomicronemia, C418Y and E421K (7, 8), might cause disease by abolishing LPL's ability to bind to GPIHBP1. Both mutations were previously reported to have little or no impact on LPL catalytic activity (7, 8). In our hands, the enzymatic specific activities of these mutant LPLs were equivalent to that of WT LPL (Fig. 1A). The preservation of catalytic activity implied that the mutant LPL proteins would form homodimers, would bind to heparin–Sepharose, and would elute from heparin–Sepharose with a NaCl gradient in a manner similar to WT LPL. Indeed, WT LPL and the mutant LPLs eluted from a heparin–Sepharose column at 1.1 to 1.2 M NaCl (characteristic of LPL homodimers) (15) (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Effect of LPL missense mutations on enzymatic activity and binding to heparin. (A) Specific activity of WT LPL, LPL-C418Y, and LPL-E421K. In control experiments, I194T and S132G mutations inhibited LPL catalytic activity, as previously reported (20, 21). (B) Elution profiles of WT LPL, LPL-C418Y, and LPL-E421K from a heparin–Sepharose column with a linear NaCl gradient. The concentration of LPL in each fraction was determined with an ELISA (15). Monoclonal antibody 5F9 was used as the capture antibody; LPL binding was detected with biotinylated antibody 5D2.

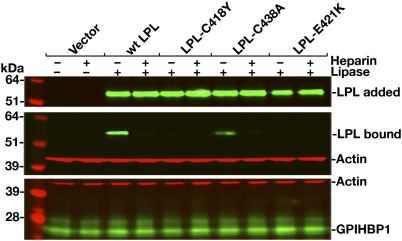

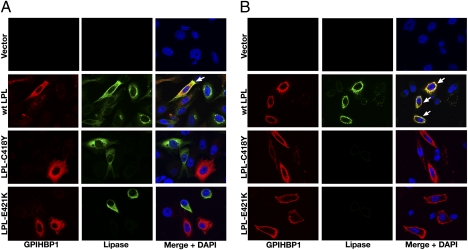

Neither LPL-C418Y nor LPL-E421K bound to GPIHBP1, as judged by Western blot (Fig. 2) or immunofluorescence microscopy (Fig. 3) assays. In contrast, WT LPL bound avidly to GPIHBP1 (Figs. 2 and 3), and this binding was inhibited with heparin (Fig. 2). The effects of the C418Y and E421K mutations were also examined in the context of a human LPL–mCherry fusion protein. The WT LPL–mCherry fusion protein bound to GPIHBP1, but fusion proteins carrying the C418Y or E421K substitutions did not (Fig. S1). The C418Y or E421K mutations also abolished GPIHBP1 binding in the context of mouse LPL (mLPL) (Fig. S2). Similarly, when the corresponding mutations (C420Y and D423K) were introduced into chicken LPL (cLPL), the binding of cLPL to GPIHBP1 was abolished (Fig. S3).

Fig. 2.

Western blot assessing binding of WT human LPL, LPL-C418Y, LPL-C438A, and LPL-E421K to GPIHBP1-transfected CHO-K1 cells in the presence or absence of heparin (500 U/mL). After a 2-h incubation, cells were washed extensively, and cell extracts were prepared for Western blotting with GPIHBP1- and LPL-specific antibodies. β-Actin levels were measured as a loading control. Top: Amount of LPL present in the conditioned medium added to the GPIHBP1-transfected CHO-K1 cells.

Fig. 3.

Immunofluorescence microscopy assay of LPL binding to GPIHBP1. CHO-K1 cells transfected with S-protein–tagged human GPIHBP1 were mixed with CHO-K1 cells transfected with WT human LPL, LPL-C418Y, or LPL-E421K and then plated on a coverslip. After a 2-h incubation at 37 °C, permeabilized (A) and nonpermeabilized (B) cells were stained for GPIHBP1 with an antibody against the S-protein tag (red) and LPL with antibody 5D2 (green). Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). WT LPL secreted by LPL-transfected cells was captured by neighboring GPIHBP1-expressing cells; thus, LPL and GPIHBP1 colocalize in the merged image (arrows). LPL-C418Y and LPL-E421K did not bind to GPIHBP1; hence, no colocalization was observed.

We also tested the ability of WT LPL, LPL-C418Y, and LPL-E421K to bind to GPIHBP1 in a cell-free system (16, 17). We mixed the LPL, soluble GPIHBP1 (i.e., GPIHBP1 lacking its GPI anchor), and agarose beads coated with the GPIHBP1-specific monoclonal antibody 11A12 and incubated them overnight. After washing the beads extensively, GPIHBP1 (along with any bound LPL) was eluted from the monoclonal antibody-coated beads with 0.1 M glycine, pH 2.5. WT LPL bound to GPIHBP1 avidly; hence, both LPL and GPIHBP1 eluted from the beads (Fig. S4). In contrast, neither LPL-C418Y nor LPL-E421K bound to soluble GPIHBP1. When the agarose beads were incubated with 0.1 M glycine, pH 2.5, only soluble GPIHBP1, and no LPL, eluted from the beads (Fig. S4).

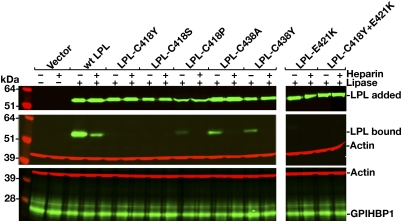

Changing human LPL Cys-418 to serine also abolished GPIHBP1 binding (Fig. 4). When Cys-418 was changed to proline, only trace amounts of GPIHBP1 binding were detectable in the Western blot assay (Fig. 4), and little or no binding was detected in the microscopy assay (Fig. S5). Cys-418 and Cys-438 are disulfide-bonded (18). Although this disulfide linkage is not required for catalysis (19), the inability of the C418Y mutant to bind GPIHBP1 raised the question of whether the disulfide bond might be essential for GPIHBP1 binding. This is apparently not the case, however, because LPL-C438A and LPL-C438Y were able to bind to GPIHBP1 (Figs. 2 and 4).

Fig. 4.

Western blot assessing binding of WT and mutant human LPLs (C418Y, C418S, C418P, C438A, C438Y, E421K, and C418Y/E421K) to GPIHBP1-transfected CHO-K1 cells in the presence or absence of heparin (500 U/mL). Quantification of signals with an Odyssey scanner showed that the binding of LPL-C438A and LPL-C438Y were reduced by 70% to 80% compared with WT LPL (n = 3 independent experiments).

Defective binding of LPL to GPIHBP1 is not a universal property of mutant LPLs associated with chylomicronemia. For example, two LPL mutations that abolish catalytic activity, I194T (20) and S132G (21), did not interfere with binding to GPIHBP1 (Fig. S6).

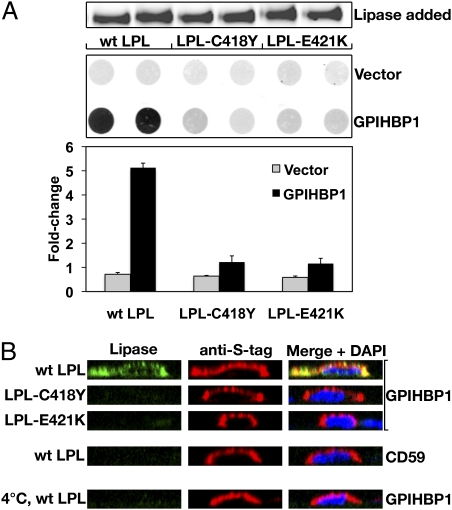

The inability of the C418Y and E421K mutants to bind to GPIHBP1-expressing CHO cells suggested that these mutations might prevent LPL transport across endothelial cells. Indeed, neither LPL-C418Y nor LPL-E421K was transported from the basolateral to the apical surface of GPIHBP1-expressing endothelial cells (as judged by the amount of LPL that was releasable by heparin from the apical surface of cells; Fig. 5A). In parallel, immunofluorescence microscopy was used to visualize LPL transport. When WT LPL was added to the basolateral medium, it was transported across cells and could be detected on the apical surface by immunofluorescence microscopy (Fig. 5B). In contrast, neither LPL-C418Y nor LPL-E421K was transported to the apical surface of GPIHBP1-expressing cells (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

WT human LPL, but not LPL-C418Y or LPL-E421K, is transported across GPIHBP1-expressing endothelial cells. (A) Ability of rat heart endothelial cells expressing S-protein–tagged versions of GPIHBP1 or CD59 to transport LPL from the basolateral to the apical surface of cells. Equal amounts of WT LPL, LPL-C418Y, or LPL-E421K were added to the basolateral side (lower side) of endothelial cell monolayers and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. Transported LPL was released from the apical surface (upper side) with heparin (100 U/mL) and dot-blotted onto nitrocellulose. LPL was detected with an antibody against V5, and the dot blots were scanned and quantified with an Odyssey infrared scanner. (B) Transport of LPL from the basolateral to the apical surface of cells, as judged by immunofluorescence microscopy. LPL was added to the basolateral side of endothelial cell that had been transfected with S-protein–tagged GPIHBP1 and grown as confluent monolayers on filters. After a 1-h incubation at 37 °C, cells were fixed and stained with antibodies against the V5 tag (green) and the S-protein (red). Apical and basolateral membranes could be visualized above and below nuclei, which were stained with Draq5 (blue). When WT LPL was added to the basolateral medium, it was transported across cells and could be detected, along with GPIHBP1, on the apical surface of cells. When LPL-C418Y or LPL-E421K was added to the basolateral medium, no transport was observed. No transport of W LPL was observed at 4 °C, or when the endothelial cells expressed CD59 rather than GPIHBP1.

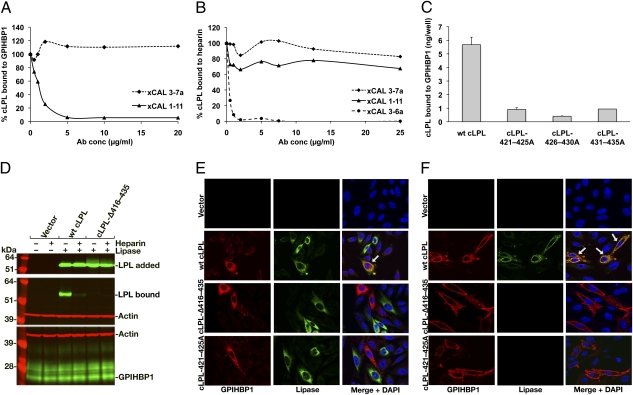

The inability of LPL-C418Y and LPL-E421K to bind to GPIHBP1 suggested that amino acid residues near the carboxyl terminus of LPL are important for GPIHBP1 binding. To explore this idea, we examined the ability of cLPL-specific monoclonal antibodies to block the binding of cLPL to GPIHBP1. Antibody xCAL 1–11 inhibited cLPL binding in a dose-dependent manner, whereas antibody xCAL 3–7a had little effect (Fig. 6A). The epitope for xCAL 1–11 is located between cLPL residues 416 and 435 [xCAL 1–11 did not bind to a cLPL mutant lacking those residues (cLPL-Δ416–435); Fig. S7]. Interestingly, xCAL 1–11 had no effect on the binding of cLPL to heparin (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Carboxyl-terminal LPL sequences are required for the binding of LPL to mouse GPIHBP1. (A) Inhibition of cLPL binding to GPIHBP1 with increasing amounts of antibody xCAL 1–11. (B) Inhibition of cLPL binding to heparin by cLPL-specific monoclonal antibody xCAL 3–6a (28), but not by antibodies xCAL 3–7a or xCAL 1–11. (C) Ability of mutant cLPLs (in which residues 421–425, 426–430, and 431–435 were changed to alanine) to bind to GPIHBP1 on the surface of transfected pgsA-745 CHO cells. The amount of LPL binding to cells was quantified with an ELISA. (D) Western blot showing that a cLPL mutant lacking residues 416 to 435 (cLPL-Δ416–435) cannot bind to GPIHBP1. (E and F) Immunofluorescence microscopy assay shows that neither cLPL-Δ416–435 nor a cLPL mutant in which residues 421 to 425 were changed to alanine was able to bind to GPIHBP1. CHO-K1 cells transfected with S-protein–tagged human GPIHBP1 were mixed with CHO-K1 cells transfected with WT or mutant cLPL constructs. After a 2-h incubation at 37 °C, permeabilized (E) and nonpermeabilized (F) cells were stained for GPIHBP1 with an antibody against the S-protein tag (red) and LPL with antibody against the V5 tag (green). Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue).

We created mutant cLPL proteins in which residues 421 to 425, 426 to 430, or 431 to 435 (corresponding to human LPL residues 419–423, 424–428, and 429–433) were changed to alanine. The enzymatic activities of the three mutant LPLs were actually higher than WT LPL (12.3 ± 2.8 mmol/mg/h), and all of the LPL preparations eluted from a heparin–Sepharose column at approximately 0.9 to 1.0 M NaCl. The binding of the “alanine mutants” to GPIHBP1 was reduced by 84% to 94%, as judged by ELISA (Fig. 6C). Consistent with these findings, binding of cLPL-Δ416–435 to GPIHBP1 was undetectable in the Western blot and immunofluorescence microscopy assays (Fig. 6 D–F). Also, a cLPL mutant in which residues 421 to 425 were changed to alanine could not bind to GPIHBP1 (Fig. 6 E and F).

Discussion

LPL mutations are known to cause chylomicronemia by blocking secretion, reducing enzyme stability, or abolishing catalytic activity (1, 5, 6). However, the peculiar nature of LPL biology—that the enzyme is produced by myocytes and adipocytes but acts inside capillaries—raises the possibility that defects in enzyme transport might occur. In the current study, we show that two LPL missense mutations initially identified in patients with severe chylomicronemia, C418Y and E421K (7, 8), abolish LPL binding to GPIHBP1 and prevent LPL transport to the apical surface of endothelial cells. Our findings are of interest for two reasons. First, they define a potential mechanism by which LPL mutations cause chylomicronemia: by preventing the delivery of a catalytically active enzyme to the luminal face of endothelial cells. Second, our findings provide insights into LPL sequences required for binding to GPIHBP1. The properties of the C418Y and E421K mutants, along with additional immunochemical and mutagenesis experiments, strongly suggest that carboxyl-terminal LPL sequences are crucial for GPIHBP1 binding.

Defective binding of the C418Y and E421K mutants to GPIHBP1 was observed in several assays. First, a Western blot assay revealed that neither of the mutant LPLs was able to bind to GPIHBP1-expressing CHO cells. Second, in an immunofluorescence microscopy assay, mutant LPL proteins secreted by CHO-K1 cells could not bind to adjacent CHO-K1 cells that expressed GPIHBP1. Third, in a cell-free assay system, we showed that WT LPL, but not LPL-C418Y or LPL-E421K, binds to soluble GPIHBP1. Fourth, the mutant LPLs were not transported from the basolateral to the apical surface of endothelial cells. Previously, we showed that point mutations in GPIHBP1 can abolish its capacity to bind LPL. The fact that defects in both a cell-surface receptor (GPIHBP1) and its ligand (LPL) would have similar consequences is noteworthy within the realm of hypertriglyceridemia, but is not particularly new for other metabolic diseases. For instance hypercholesterolemia can be caused by point mutations in both the LDL receptor and its apolipoprotein ligands (22–24).

Beigneux and coworkers (17, 25) showed that defects in either of GPIHBP1’s two principal domains (the acidic domain or the cysteine-rich Ly6 domain) are sufficient to abolish LPL binding, and they speculated that GPIHBP1’s ability to bind LPL requires both domains. They further speculated, by analogy, that two distinct domains in LPL might be required for binding to GPIHBP1. Our current studies, in combination with an earlier study by Gin et al. (25), support this view. Gin et al. (25) found that mutation of Lys-403, Arg-405, and Lys-407, the key residues in LPL's main heparin-binding domain, reduce LPL binding to GPIHBP1 (25). Presumably, LPL's positively charged heparin-binding domain interacts with GPIHBP1’s acidic domain (in which 21 of 26 residues are aspartate or glutamate). In the current study, we show that a second region of LPL, located downstream from its main heparin-binding domain, is important for GPIHBP1 binding. Mutation of C418 or E421 abolished GPIHBP1 binding without affecting catalytic activity or binding to heparin. Similarly, changing cLPL residues 420 to 425, 426 to 430, or 430 to 435 to alanine blocked GPIHBP1 binding without hindering catalytic activity. Finally, a cLPL-specific monoclonal antibody with an epitope between residues 416 and 435 blocked LPL binding to GPIHBP1 but not to heparin. Thus, in addition to LPL's principal heparin-binding domain, downstream sequences are required for GPIHBP1 binding. We hypothesize that the latter sequences interact with GPIHBP1’s Ly6 domain. Evaluating that hypothesis, however, and fully elucidating the two-domain postulate for LPL–GPIHBP1 interactions, will likely require cocrystallization of LPL and GPIHBP1.

Cysteines 418 and 438 are disulfide-bonded (18). These cysteines are conserved in the LPL of nearly all vertebrates, and also in hepatic lipase, which does not bind to GPIHBP1 (16). The C418–C438 linkage is not required for catalytic activity (19), but the inability of LPL-C418Y to bind to GPIHBP1 prompted us to consider whether the disulfide bond is required for GPIHBP1 binding. Contrary to our expectations, the disulfide bridge did not appear to be crucial. Although mutations of Cys-418 fully blocked GPIHBP1 binding, Cys-438 mutants retained at least partial ability to bind to GPIHBP1. Again, understanding the precise importance of this carboxyl-terminal disulfide bond on GPIHBP1 binding will probably require cocrystallization studies.

In summary, we have shown that a pair of LPL mutations originally identified in patients with severe chylomicronemia, C418Y and E421K (7, 8), abolish GPIHBP1 binding, uncovering an exciting mechanism for disease. Neither mutation had significant effects on heparin binding or catalytic activity. These findings, along with additional immunochemical and mutagenesis experiments, suggest that a carboxyl-terminal segment of LPL distinct from the heparin-binding domain is required for GPIHBP1 binding.

Materials and Methods

Assessment of LPL Binding to GPIHBP1.

Binding of V5-tagged LPL to S-protein–tagged GPIHBP1 was assessed by Western blot and immunofluorescence microscopy assays. LPL mutants were generated with the QuikChange Lightning kit (Agilent). LPL was expressed in transiently transfected CHO-K1 or Chinese hamster lung cells (American Type Culture Collection). For the Western blot assay, LPL was incubated with GPIHBP1-transfected CHO-K1 cells for 2 h at 4 °C with or without heparin (500 U/mL). After washing the cells, the amounts of LPL bound to the cells were assessed by Western blots (26) with monoclonal antibodies against LPL (5D2) (26) or the V5 tag (Invitrogen). GPIHBP1 expression was assessed with an S-protein antibody (Abcam). A rabbit antibody against β-actin (Abcam) was used as a loading control. Antibody binding was detected with IR dye-conjugated secondary antibodies (Li-Cor) and an Odyssey infrared scanner (Li-Cor).

For the immunofluorescence microscopy assay (16), cells transfected with WT GPIHBP1 were mixed with cells transfected with WT or mutant LPL and then plated on coverslips (25,000 cells/well) in 24-well plates. After incubating the cells overnight at 37 °C, cells were fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde, blocked in 10% donkey serum, and incubated with the goat antibody against the S-protein tag (to detect GPIHBP1) and antibody 5D2 (to detect LPL). In some experiments, cells were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100. Binding of primary antibodies was detected with Alexa Fluor 568-labeled donkey anti-goat IgG and Alexa Fluor 488-labeled donkey anti-mouse IgG. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI. In some experiments, we assessed the binding of LPL–mCherry fusion proteins. Images were obtained with an Axiovert 200 MOT microscope (Zeiss) with a 63×/1.25 oil immersion objective and processed with AxioVision 4.2 software (Zeiss).

We also tested the ability of WT LPL, C418Y-LPL, and E421K-LPL in a cell free binding assay (16, 17). Soluble mouse GPIHBP1 (no GPI anchor) and 20 μL of concentrated medium containing V5-tagged human LPL preparations were incubated overnight with 40 μL of antibody 11A12-coated agarose beads in 200 μL of PBS solution containing 0.2% Nonidet P-40 (17, 25). The beads were washed three times in PBS solution containing 0.2% Nonidet P-40. The antibody-bound GPIHBP1 (along with any LPL that had been bound by GPIHBP1) was eluted from the beads with 200 μL of 0.1 M glycine, pH 2.5 (this step was repeated three times). The amounts of GPIHBP1 and LPL in each fraction were assessed by Western blotting.

The binding of cLPL to mouse GPIHBP1-transfected cells was assessed as previously described (10). For these studies, cLPL was partially purified from the medium of transfected CHO cells by heparin–Sepharose chromatography and concentrated by ammonium sulfate precipitation. cLPL preparations were added to GPIHBP1-transfected cells and incubated for 2 h at 4 °C. The cells were then washed twice with 3% BSA/PBS solution and incubated for 15 min at 4 °C with BSA/PBS solution containing heparin (100 U/mL). The heparin-released cLPL was measured with an ELISA (27). In some experiments, binding of cLPL to GPIHBP1-expressing cells was tested in the presence of immunopurified cLPL-specific monoclonal antibodies (28).

We also tested the ability of the cLPL-specific monoclonal antibodies to block binding of cLPL to heparin. Plates (96-well) were coated with heparin (25 μg/well) for 7 d at 4 °C. Monoclonal antibodies (0–25 μg/mL) were preincubated with cLPL for 1 h at 4 °C, and then incubated in heparin-coated wells overnight at 4 °C. The amount of LPL bound to each well was quantified by ELISA with a goat antiserum against cLPL (27).

LPL Catalytic Activity and Heparin Binding.

CHL cells were electroporated with WT or mutant LPL constructs (2.0 μg of DNA for 3 × 106 cells) and plated in six-well dishes. After 4 h, the medium was replaced with Ham F-12 medium containing heparin (5 U/mL). After an overnight incubation, the medium was collected and concentrated 10-fold. Catalytic activity was measured with a [3H]triolein substrate (29). Specific activities were calculated after measuring LPL mass with an ELISA (10). The elution of LPL from a 1.0-mL heparin–Sepharose column with a NaCl gradient was assessed as previously described (10).

LPL Transport Across Endothelial Cells.

Rat heart microvascular endothelial cells transduced with a GPIHBP1 lentivirus were grown on fibronectin-coated Millicell filters (polyethylene terephthalate, 1.1 cm2 filtration area, 1 μm pore size; Millipore) until they formed tight monolayers (11). After adding V5-tagged LPL to the basolateral chamber and PBS solution to the apical chamber, the cells were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The LPL transported to the apical surface of cells was released with heparin (100 U/mL for 5 min) and quantified as described previously (11). Transport was also assessed by microscopy. For these studies, endothelial cells were transfected with S-protein–tagged versions of GPIHBP1 or CD59 and grown on the Millicell filters. LPL was added to the basolateral chamber. After a 1-h incubation at 37 °C, a monoclonal antibody against the V5 tag was added to the apical chamber. After washing, the binding of this antibody to LPL on the apical surface of cells was detected by immunofluorescence microscopy. Cells expressing GPIHBP1 were identified with an antibody against the S-protein tag. Nuclei were visualized using Draq5 (Cell Signaling Technology). Stacks along the Z plane were recorded with an Axiovert 200 MOT microscope (Zeiss) with a 63×/1.25 oil immersion objective and processed with AxioVision 4.6 software (Zeiss). Cross-sections of endothelial cells were generated with Volocity Visualization software (version 5.3; Perkin-Elmer).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank John Brunzell for antibodies 5D2 and 5F9. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HL090553, HL087228, and HL094732; Scientist Development Award 0735026N from the American Heart Association's National Office; and a fellowship award from the American Heart Association, Western States Affiliate.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1100992108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Brunzell JD, Deeb SS. Familial lipoprotein lipase deficiency, apo C-II deficiency, and hepatic lipase deficiency. In: Scriver CR, et al., editors. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. 8th Ed. Vol 2. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001. pp. 2789–2816. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merkel M, Eckel RH, Goldberg IJ. Lipoprotein lipase: Genetics, lipid uptake, and regulation. J Lipid Res. 2002;43:1997–2006. doi: 10.1194/jlr.r200015-jlr200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang H, Eckel RH. Lipoprotein lipase: From gene to obesity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;297:E271–E288. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90920.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Havel RJ, Gordon RS., Jr Idiopathic hyperlipemia: Metabolic studies in an affected family. J Clin Invest. 1960;39:1777–1790. doi: 10.1172/JCI104202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayden MR, Ma Y, Brunzell J, Henderson HE. Genetic variants affecting human lipoprotein and hepatic lipases. Curr Opin Lipidol. 1991;2:104–109. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fojo SS, Brewer HB. Hypertriglyceridaemia due to genetic defects in lipoprotein lipase and apolipoprotein C-II. J Intern Med. 1992;231:669–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1992.tb01256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henderson H, Leisegang F, Hassan F, Hayden M, Marais D. A novel Glu421Lys substitution in the lipoprotein lipase gene in pregnancy-induced hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis. Clin Chim Acta. 1998;269:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(97)00144-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henderson HE, Hassan F, Marais D, Hayden MR. A new mutation destroying disulphide bridging in the C-terminal domain of lipoprotein lipase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;227:189–194. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu MS, Ma Y, Hayden MR, Brunzell JD. Mapping of the epitope on lipoprotein lipase recognized by a monoclonal antibody (5D2) which inhibits lipase activity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1128:113–115. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(92)90264-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beigneux AP, et al. Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored high-density lipoprotein-binding protein 1 plays a critical role in the lipolytic processing of chylomicrons. Cell Metab. 2007;5:279–291. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davies BSJ, et al. GPIHBP1 is responsible for the entry of lipoprotein lipase into capillaries. Cell Metab. 2010;12:42–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olivecrona G, et al. Mutation of conserved cysteines in the Ly6 domain of GPIHBP1 in familial chylomicronemia. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:1535–1545. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M002717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franssen R, et al. Chylomicronemia with low postheparin lipoprotein lipase levels in the setting of GPIHBP1 defects. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2010;3:169–178. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.908905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beigneux AP, et al. Chylomicronemia with a mutant GPIHBP1 (Q115P) that cannot bind lipoprotein lipase. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:956–962. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.186577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peterson J, Fujimoto WY, Brunzell JD. Human lipoprotein lipase: Relationship of activity, heparin affinity, and conformation as studied with monoclonal antibodies. J Lipid Res. 1992;33:1165–1170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gin P, et al. Binding preferences for GPIHBP1, a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein of capillary endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:176–182. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.214718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beigneux AP, et al. Highly conserved cysteines within the Ly6 domain of GPIHBP1 are crucial for the binding of lipoprotein lipase. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:30240–30247. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.046391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang CY, et al. Structure of bovine milk lipoprotein lipase. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:16822–16827. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lo JY, Smith LC, Chan L. Lipoprotein lipase: role of intramolecular disulfide bonds in enzyme catalysis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;206:266–271. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henderson HE, et al. Amino acid substitution (Ile194----Thr) in exon 5 of the lipoprotein lipase gene causes lipoprotein lipase deficiency in three unrelated probands. Support for a multicentric origin. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:2005–2011. doi: 10.1172/JCI115229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Emmerich J, et al. Human lipoprotein lipase. Analysis of the catalytic triad by site-directed mutagenesis of Ser-132, Asp-156, and His-241. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:4161–4165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldstein JL, Brown MS. The LDL receptor locus and the genetics of familial hypercholesterolemia. Annu Rev Genet. 1979;13:259–289. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.13.120179.001355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Utermann G, Hees M, Steinmetz A. Polymorphism of apolipoprotein E and occurrence of dysbetalipoproteinaemia in man. Nature. 1977;269:604–607. doi: 10.1038/269604a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soria LF, et al. Association between a specific apolipoprotein B mutation and familial defective apolipoprotein B-100. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:587–591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.2.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gin P, et al. The acidic domain of GPIHBP1 is important for the binding of lipoprotein lipase and chylomicrons. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:29554–29562. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802579200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang S-F, Reich B, Brunzell JD, Will H. Detailed characterization of the binding site of the lipoprotein lipase-specific monoclonal antibody 5D2. J Lipid Res. 1998;39:2350–2359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cisar LA, Hoogewerf AJ, Cupp M, Rapport CA, Bensadoun A. Secretion and degradation of lipoprotein lipase in cultured adipocytes. Binding of lipoprotein lipase to membrane heparan sulfate proteoglycans is necessary for degradation. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:1767–1774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sendak RA, Melford K, Kao A, Bensadoun A. Identification of the epitope of a monoclonal antibody that inhibits heparin binding of lipoprotein lipase: New evidence for a carboxyl-terminal heparin-binding domain. J Lipid Res. 1998;39:633–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hocquette JF, Graulet B, Olivecrona T. Lipoprotein lipase activity and mRNA levels in bovine tissues. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 1998;121:201–212. doi: 10.1016/s0305-0491(98)10090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.