Abstract

Following endocytosis, the fates of receptors, channels, and other transmembrane proteins are decided via specific endosomal sorting pathways, including recycling to the cell surface for continued activity. Two distinct phox-homology (PX)-domain-containing proteins, sorting nexin (SNX) 17 and SNX27, are critical regulators of recycling from endosomes to the cell surface. In this study we demonstrate that SNX17, SNX27, and SNX31 all possess a novel 4.1/ezrin/radixin/moesin (FERM)-like domain. SNX17 has been shown to bind to Asn-Pro-Xaa-Tyr (NPxY) sequences in the cytoplasmic tails of cargo such as LDL receptors and the amyloid precursor protein, and we find that both SNX17 and SNX27 display similar affinities for NPxY sorting motifs, suggesting conserved functions in endosomal recycling. Furthermore, we show for the first time that all three proteins are able to bind the Ras GTPase through their FERM-like domains. These interactions place the PX-FERM-like proteins at a hub of endosomal sorting and signaling processes. Studies of the SNX17 PX domain coupled with cellular localization experiments reveal the mechanistic basis for endosomal localization of the PX-FERM-like proteins, and structures of SNX17 and SNX27 determined by small angle X-ray scattering show that they adopt non-self-assembling, modular structures in solution. In summary, this work defines a novel family of proteins that participate in a network of interactions that will impact on both endosomal protein trafficking and compartment specific Ras signaling cascades.

Phox-homology (PX) domain-containing proteins are a diverse family of proteins implicated in many protein trafficking processes, and there is emerging recognition of their importance in cell signaling (1, 2). The PX domain binds phosphatidylinositol phospholipids (PIPs) to mediate localization to subcellular membranous compartments for regulation of cargo transport and processing. Most PX proteins also contain a variety of other functional modules including Ras-association (RA) and PSD-95/discs large/zona occludens (PDZ) domains. Thus PX proteins can function as scaffolds that facilitate spatiotemporal assembly of membrane trafficking and signaling complexes.

The PX-protein sorting nexin 17 (SNX17) is important for endosomal sorting of transmembrane proteins from endosomes to the cell surface. Identified cargo molecules include the low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR), and other members of the LDLR family including LDLR-related protein 1 (LRP1), suggesting an important role in lipid metabolism (3–5). SNX17 also regulates the trafficking of P-selectin (6) and FEEL-1 (7) and associates with cytosolic factors Krit1 (8) and Kif1B (9). All of these proteins have been found to bind SNX17 via a conserved Asn-Pro-Xaa-Tyr (NPxY) sequence motif, but the molecular basis of this interaction is unknown. Recent data indicate an important role for SNX17 in trafficking of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) central to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (10). As the LDLR family, in particular LRP1, have also been linked to AD and play direct roles in APP trafficking (11, 12), it appears SNX17 functions at a nexus of endosomal trafficking pathways important for the disease. The homology of SNX31 to SNX17 (approximately 40% identity) suggests an involvement in similar endosomal transport pathways.

SNX27 is unique among the PX proteins, containing an N-terminal PDZ domain upstream of the PX domain. SNX27 has also been annotated to possess a Ras-association domain and extended C-terminal region (1, 2, 13). SNX27 was first identified as a binding partner for the 5-hydroxytryptamine type-4 receptor (5-HT4R) (13), and overexpression of SNX27 directs localization of 5-HT4R and Kir3 potassium channels to early endosomal autoantigen 1 (EEA1)-positive early endosomes (13, 14). There is accumulating evidence for a role for SNX27 in coupling protein sorting to cell signaling. It can direct the endosome-to-cell surface recycling of the β2 adrenergic receptor (15), and SNX27 may also scaffold signaling and lipid modulating complexes by interacting with proteins such as diacylglycerolkinase ζ (16), NMDA receptors (17), and cytohesin associated scaffolding protein (CASP) (18). All of these molecules bind to SNX27 via type-I PDZ-domain binding motifs.

Recent studies suggest that some PX proteins may play dual roles in membrane trafficking and cell signaling (19, 20), and there is mounting evidence that endosomal sorting of receptors is a key factor in determining differential signaling outcomes (21, 22). For example, signaling by the Ras oncogene has for many years been thought to occur primarily at the plasma membrane. More recent assessments of the spatiotemporal control of Ras signaling have demonstrated the existence of Ras-mediated signaling events on intracellular membranes including Ras/MAPK signaling on endosomes (23, 24).

Here we show that SNX17, SNX27, and SNX31 define a unique subfamily of PX proteins possessing an unusual band 4.1/ezrin/radixin/moesin (FERM)-like structure, which incorporates the previously annotated Ras-association domain of SNX27. We find that the members of this family share both NPxY peptide-binding properties and an ability to associate with H-Ras in a GTP-dependent manner. Structural studies of the PX-FERM-like proteins reveal the molecular mechanisms for membrane recruitment and their overall domain architectures, highlighting a structural scaffold primed for assembly of endosomal trafficking and signaling complexes. Our work points to a role for PX-FERM-like proteins as interaction hubs that will have key functions in endosomal trafficking and Ras-mediated signaling and provides a foundation for future studies of these processes.

Results

Defining a Unique PX-FERM-Like Protein Family.

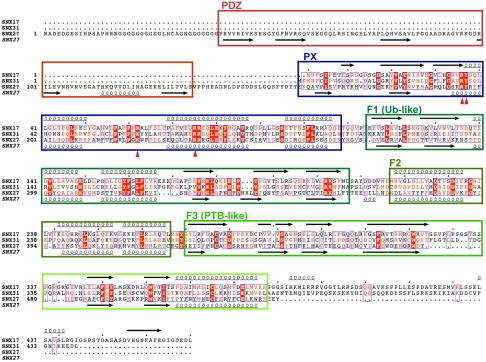

FERM domains are found in numerous molecules where they regulate lipid and protein interactions. They are approximately 300 residues in length and contain three modules termed F1, F2, and F3 (25). F1 has a ubiquitin-related fold, F2 an α-helical structure, and F3 has structural similarity to phosphotyrosine-binding (PTB) domains. Both SNX17 and SNX31 have been annotated to possess a C-terminal sequence similar to the N terminus of FERM domains (1, 2, 6, 8). We performed a secondary structure-based comparison of SNX17 and SNX31 and found that the C-terminal region of both proteins, in fact, contains canonical F1 and F3 structures (Fig. 1). However, unlike classical FERM domains, SNX17 and SNX31 possess an altered F2 module. Instead of four helices, the F2 modules of SNX17 and SNX31 are predicted to have three and are shorter in length than the canonical F2 structure (approximately 50 rather than approximately 100 residues). Thus SNX17 and SNX31 possess all of the expected features of the FERM domain but with an altered F2 module, and we propose that this domain be referred to as a “FERM-like” domain to reflect this difference. Similar analyses of other PX proteins unexpectedly showed that SNX27 has a homologous FERM-like domain (Fig. 1). SNX27 has been annotated to possess a C-terminal RA domain (1, 2) and has an additional N-terminal PDZ domain. This bioinformatics-based classification likely results from the high degree of structural homology between the RA domain and the FERM F1 module (26). In summary, SNX17, SNX27, and SNX31 form a distinct subfamily of PX proteins with a conserved FERM-like structure.

Fig. 1.

SNX17, SNX31, and SNX27 share a conserved C-terminal FERM-like domain. Sequence alignment of SNX17, SNX27, and SNX31. Secondary structure predictions calculated with JPRED (41) are indicated for SNX17 (above) and SNX27 (below). Alignment was made with ESPript 2.2 (42). Identified subdomains are indicated by boxes. Red triangles indicate key residues involved in PI(3)P binding.

Interactions of PX-FERM-Like Proteins with NPxY-Containing Cargo Molecules.

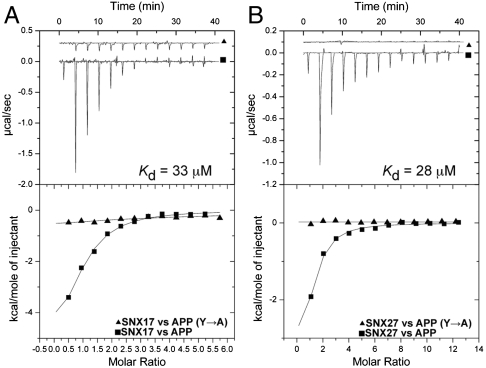

SNX17 associates with transmembrane cargo proteins by recognizing an NPxY motif present in their cytosolic tails (4, 5, 10). To examine the affinity of this interaction we used isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) to monitor the interaction between SNX17 and a 15-mer peptide derived from the model cargo protein APP (Fig. 2A and Table S1). Significant binding was observed with a Kd of 32 ± 5 μM. This low micromolar affinity is typical of coat–cargo interactions in other systems such as clathrin-coated vesicle formation. Titrations using a peptide in which the key Tyr side chain was mutated to Ala showed no significant binding, confirming the specificity of the interaction. Previous reports have indicated that the C terminus of SNX17 is required for NPxY binding (6, 8), but the mechanism underpinning this interaction is unknown. As we have found that this region contains a FERM-like domain with a PTB-related F3 module, it is highly likely that this interaction occurs via binding to this structure, as observed in the complex formed between the FE65 PTB domain and APP (27). To investigate if other PX-FERM-like proteins also interact with cargo receptors containing the NPxY motif, SNX27 was titrated with the APP NPxY peptide (Fig. 2B). SNX27 bound the APP peptide with similar affinity to SNX17 (Kd = 27.6 ± 0.1 μM), and the SNX27 FERM-like domain binds the APP peptide sequence with almost identical affinity to the full-length protein (Kd = 22.9 ± 13.4 μM). To date, SNX27 has been found to bind cargo only via its PDZ domain; hence we show that like SNX17, SNX27 is able to associate specifically with NPxY motif-containing cargo receptors.

Fig. 2.

Binding of NPxY cargo motifs is conserved across the PX-FERM-like protein family. Binding of SNX17 (A) and SNX27 (B) to a peptide derived from APP was measured using ITC. Experiments were performed at 10 °C with 50 μM protein and 2,000 μM APP peptide. Also shown are the titrations of SNX17 and SNX27 with the APP Y*A mutant peptide, which does not bind. (Top) Raw data; (Bottom) integrated normalized data.

PX-FERM-Like Proteins Interact with H-Ras in Vitro via Their FERM-Like Domain.

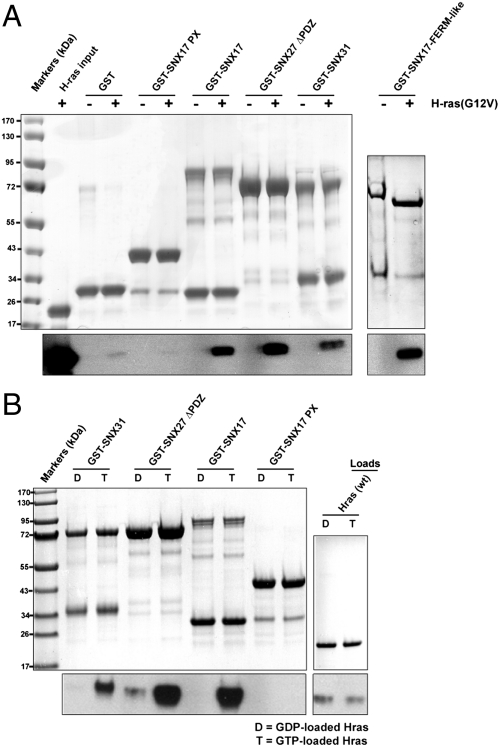

As the F1 module of SNX27 was originally detected as a putative Ras-binding RA domain (1, 2), we examined whether the PX-FERM-like proteins have Ras-binding activity. The interaction of H-Ras with the PX-FERM-like proteins was investigated in vitro using GST pulldown assays and Western blotting. For these experiments, soluble H-Ras truncated at residue 166 and with a G12V activating mutation (26) was tested against GST-SNX17, GST-SNX27ΔPDZ, and GST-SNX31 (Fig. 3A). The PX-FERM-like proteins all showed binding to H-Ras(G12V) in these experiments. No binding to GST-SNX17-PX was observed, and a GST-SNX17-FERM-like domain construct bound similarly to full-length SNX17, indicating that the binding of H-Ras occurs via the FERM-like domain as predicted. The lack of both stoichiometric amounts of H-Ras in pulldowns (Fig. 3A) and strong binding signals by ITC indicate that the interactions are of relatively low affinity (Kd > 50–100 μM). An essential attribute of Ras effector proteins is that they bind active GTP-loaded Ras but not inactive GDP-loaded Ras. To test this we used H-Ras loaded with either GTP or GDP and found that all three PX-FERM-like proteins associate specifically with GTP-loaded H-Ras (Fig. 3B). This indicates they are likely bona fide effector molecules and suggests that apart from being involved in membrane trafficking, PX-FERM-like proteins could also play key roles in Ras-mediated endosomal signal transduction.

Fig. 3.

PX-FERM-like proteins are effectors of the Ras GTPase. (A) PX-FERM-like proteins were tested for H-Ras(G12V) binding in GST pulldown assays. (Top) Coomassie-stained gel of the pulldown samples; (Lower) Western blot with anti-Ras antibody. Note the SNX27 construct lacks the N-terminal PDZ domain. A minimal SNX17-FERM-like domain associates with H-Ras similarly to the full-length PX-FERM-like proteins. (B) The GTP dependence of the interaction was confirmed by loading H-Ras with either GDP or GTP and performing GST-pulldown assays as in A.

PX Domains of PX-FERM-Like Proteins Bind Specifically to PI(3)P.

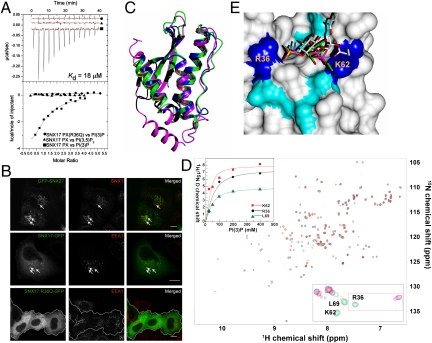

Critical to the function of PX-domain proteins is their ability to be recruited to specific intracellular membranes via binding of the PX domain to PIPs. Liposome pelleting assays indicate a distinct preference for PI(3)P lipids (Fig. S1). The PIP specificity of SNX17 and SNX27 was quantified by ITC using soluble short-chain (di-C8) analogues (Fig. 4A and Table S1). The SNX17 and SNX27 PX domains were found to interact only with PI(3)P, with almost identical thermodynamics and affinities (11.3 ± 2.1 μM and 12.7 ± 4.5 μM, respectively). These data are consistent with observations that SNX17 and SNX27 both localize to PI(3)P-rich endosomal membranes (Fig. 4B and Fig. S2). Experiments using inositol(1,3)P2 lacking the di-C8 hydrocarbon chain show that the lipid acyl chain does not contribute to the interaction. Finally, full-length SNX17 and SNX27 bound PI(3)P with the same affinity as the isolated PX domain, indicating that the interaction with PI(3)P lipids is solely driven by the PX domains.

Fig. 4.

PX-FERM-like proteins bind specifically to endosomal PI(3)P phosphoinositides. (A) Binding of the SNX17 PX domain to PI(3)P measured by ITC at 25 °C. Data are shown for protein versus PI(3)P, and PI(3,5)P2, which does not bind. Also shown is the R36Q mutant, confirming it does not bind PI(3)P. (Top) Raw data; (Bottom) integrated normalized data. A full list of binding results is given in Table S1. (B) SNX27-GFP and GFP-SNX17 were examined for colocalization with early endosomal markers SNX1 and EEA1, respectively, using immunofluorescence microscopy. SNX17(R36Q)-GFP shows only cytosolic localization. Comparison with other cellular markers is shown in Fig. S5. (C) Ribbon representation of the superposition of SNX17 PX crystal structure (blue), SNX9-PX [green; (28)], and p40phox-PX [magenta; (43)]. (D) A superposition of the 1H-15N HSQC spectra of free (green) and PI(3)P-saturated SNX17 PX domain (red). (Bottom Right Inset) Chemical shift changes in the backbone amide resonances of Arg36, Lys62, and Lys69 with increasing PI(3)P concentration. The binding curves for these residues were plotted to show the chemical shift (Δδ) as a function of PI(3)P concentration (Top Left Inset). (E) Surface representation of the SNX17 PX domain highlighting residues showing significant chemical shift changes in blue (2× SD) and cyan (1× SD). The HADDOCK docked PI(3)P molecule (green) displays clear overlap with the bound  ion in the crystal structure (yellow) and PI(3)P from the SNX9∶PI(3)P complex (white).

ion in the crystal structure (yellow) and PI(3)P from the SNX9∶PI(3)P complex (white).

Molecular Mechanism of Endosomal PI(3)P Binding.

To assess the molecular determinants for PX-FERM-like protein membrane interaction, the structure of the SNX17-PX domain was determined by X-ray crystallography (Fig. 4C, Fig. S3, and Table S2). The SNX17 PX domain has a conventional PX-domain fold with a meander topology consisting of an N-terminal three-stranded β-sheet (β1: Phe3-Arg11, β2: Tyr20-Val27, and β3: Val30-Val35) followed by a helical bundle (α1: Tyr37-Tyr51, α2: Pro69-Gln88, and α3: Gln96-Thr109) and a 310 helix. In addition, there is a long loop (Tyr52-Thr68) containing a polyproline region that connects helices α1 and α2.

Each of the three chains of SNX17-PX in the crystallographic asymmetric unit contain bound  ions forming electrostatic interactions with Arg36 (Fig. S3). The

ions forming electrostatic interactions with Arg36 (Fig. S3). The  ion lies in a positively charged cavity formed between α1, β3, and α2 and the adjacent polyproline loop. Overlay of SNX17 and SNX9 (rmsd of 1.66 Å over 95 Cα atoms) shows that the bound

ion lies in a positively charged cavity formed between α1, β3, and α2 and the adjacent polyproline loop. Overlay of SNX17 and SNX9 (rmsd of 1.66 Å over 95 Cα atoms) shows that the bound  ion is oriented identically to the 3 phosphate of the PI(3)P bound to SNX9 (Fig. 4 and Fig. S3) (28). Other critical side chains are also conserved in SNX17, including Tyr37, which in SNX9 forms a stacking interaction with the inositol ring of PI(3)P, Arg75, which contributes to the environment of the binding pocket, and Lys62, which forms an electrostatic contact with the 1-phosphate group. The electrostatic surface of SNX17 also shows a very similar electropositive binding pocket to SNX9 (Fig. S3).

ion is oriented identically to the 3 phosphate of the PI(3)P bound to SNX9 (Fig. 4 and Fig. S3) (28). Other critical side chains are also conserved in SNX17, including Tyr37, which in SNX9 forms a stacking interaction with the inositol ring of PI(3)P, Arg75, which contributes to the environment of the binding pocket, and Lys62, which forms an electrostatic contact with the 1-phosphate group. The electrostatic surface of SNX17 also shows a very similar electropositive binding pocket to SNX9 (Fig. S3).

We next used a combination of heteronuclear NMR experiments and molecular docking to determine the structure of the SNX17:PI(3)P complex. Complete 15N, 13C, and 1H resonance assignments were obtained for the SNX17 PX domain (Fig. S4), which enabled NMR chemical shift mapping to determine the identity of the diC8-PI(3)P binding site (Fig. 4D). These NMR titration experiments yielded a Kd of 20 ± 10 μM, which is very similar to that obtained by ITC. Those residues that incurred the largest 15N and HN chemical shift changes upon addition of PI(3)P were mapped onto the crystal structure to identify the putative PI(3)P binding pocket (Fig. 4E and Fig. S5). These residues were used as restraints to dock PI(3)P onto the SNX17 crystal structure to obtain a model of the SNX17:PI(3)P complex (details in SI Text). The 3 phosphate of the docked PI(3)P overlaps very well with the  molecule bound to the SNX17 PX domain in our crystal structure (Fig. 4E). It also very closely matches the previously solved structure of the SNX9:PI(3)P complex (28). Overall then, we confidently predict that SNX17 (and SNX27 and SNX31) coordinates PI(3)P in a very similar manner to SNX9 and other members of the PX-protein family. The identity of the PI(3)P binding site was further confirmed by the finding that the binding of SNX17 to PI(3)P (Fig. 4A) and SNX17 localization in vivo (Fig. 4B) were both completely abrogated when the critical Arg36 was mutated to Gln.

molecule bound to the SNX17 PX domain in our crystal structure (Fig. 4E). It also very closely matches the previously solved structure of the SNX9:PI(3)P complex (28). Overall then, we confidently predict that SNX17 (and SNX27 and SNX31) coordinates PI(3)P in a very similar manner to SNX9 and other members of the PX-protein family. The identity of the PI(3)P binding site was further confirmed by the finding that the binding of SNX17 to PI(3)P (Fig. 4A) and SNX17 localization in vivo (Fig. 4B) were both completely abrogated when the critical Arg36 was mutated to Gln.

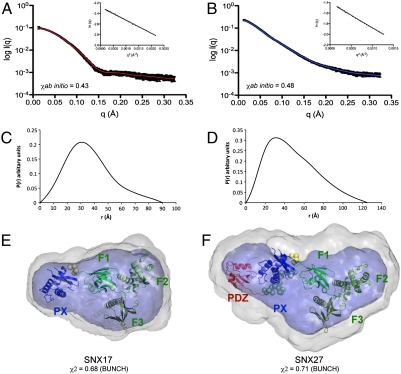

Solution Structures of Full-Length PX-FERM-Like Proteins.

The PX-FERM-like proteins represent a unique family with as yet poorly understood intradomain architectures and tertiary structures. As many PX-domain proteins are known to self-associate, we first examined their oligomeric properties using multiangle laser light scattering, confirming the monomeric nature of both SNX17 and SNX27 (Table S3 and Fig. S6). We next used small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) to examine the solution structures of full-length SNX17 and SNX27. Scattering curves and Guinier plots are shown in Fig. 5 A and B, and structural parameters are summarized in Table S3. Pair distance distribution functions, P(r), indicate that both SNX17 and SNX27 possess a compact globular conformation in solution (Fig. 5 C and D). The radius of gyration (Rg) and maximum dimensions (Dmax) of SNX17 are significantly smaller than SNX27, likely due to the presence of the additional PDZ domain in SNX27. The ab initio structures of both SNX17 and SNX27 calculated with GASBOR display distinctive features, where a larger globular domain is apposed to a smaller globular domain in the case of SNX17 or a more extended structure in the case of SNX27 (Fig. 5 E and F). A starting model composed of the SNX17 PX domain and radixin FERM domain was docked into the SNX17 SAXS-derived envelope by treating the PX and FERM domains as distinct rigid bodies. The derived structure shows excellent agreement with the ab initio model and confirms that SNX17 has a compact architecture with closely associated PX and FERM-like domains (Fig. 5E). Similarly we determined the solution structure of SNX27, with an N-terminal PDZ domain added to the SNX17 structure, and modeling against the SNX27 SAXS data treating the PDZ, PX, and FERM-like domains as separate rigid entities. The refined PDZ, PX, and FERM-like domains form a roughly linear overall structure, in excellent agreement with the observed scattering data (Fig. 5F). These results show that SNX17 and SNX27 possess analogous structures comprising the PX and FERM-like domains in close contact with each other, whereas the N-terminal PDZ domain of SNX27 extends the protein significantly, but also appears to be closely associated with the PX and FERM-like domains in a relatively rigid arrangement.

Fig. 5.

SAXS data and molecular models of the SNX17 and SNX27 proteins. (Top) Experimental SAXS scattering profiles for SNX17 (A) and SNX27 (B) after averaging and subtracting solvent scattering contribution. Theoretical scattering curves calculated from the ab initio models with lowest χ value (solid lines) overlaid on the experimental scattering data (black). (Insets) Guinier plots at the low-angle region (qmax × Rg < 1.3). (Middle) P(r) functions for SNX17 (C) and SNX27 (D). (Lower) Ab initio models for SNX17 (E) and SNX27 (F) as transparent surfaces. Averaged and filtered envelopes from GASBOR are shown in gray and blue, respectively. The domain models derived from BUNCH are overlaid with the ab intio structures, with PX and FERM domains colored blue and green, respectively, and the PDZ domain colored red.

Discussion

A number of studies have confirmed the importance of the PX proteins SNX17 and SNX27 in distinct endosome-to-cell surface recycling processes. In contrast to previous reports we show that the C-terminal regions of SNX17, SNX27, and the homologue SNX31 have a FERM-like domain analogous to the classical FERM domain, but with an altered F2 module, and share similar abilities to bind to NPxY cargo motifs. Canonical FERM domains recognize a variety of peptide signals including NPxY via the PTB domain-like F3 module (29); therefore, our determination that the PX-FERM-like proteins possess an F3 module as opposed to a truncated FERM domain provides a likely mechanism for NPxY signal binding by the proteins. SNX27 was previously shown to use its PDZ domain to bind transmembrane and cytosolic proteins with type-I PDZ binding motifs (13, 15, 16, 18); thus the demonstration of SNX27’s ability to also bind NPxY motifs significantly expands the range of potential cargo molecules for this protein. It will be important to determine if the three PX-FERM-like proteins have overlapping roles in endosomal sorting of NPxY-containing proteins or whether they have different functions mediated via regulatory interactions, alternate expression patterns, or tissue distributions.

Several studies have demonstrated that endosomal localization of SNX17 and SNX27 is essential for regulating trafficking of cargo molecules (4, 5, 8, 13, 14, 16). Our ITC and NMR titration data demonstrate the exclusive binding of the PX domains of SNX17 and SNX27 to PI(3)P, and structural modeling confirms SNX17 binds PI(3)P via a conserved mechanism relying on specific recognition of the 3 phosphate and exclusion of potential 4- and 5-phosphate moieties. The association of SNX17 and SNX27 with PI(3)P explains their interaction with PI(3)P-enriched endosomal membranes, and this depends on a functional PX domain.

An intriguing finding of this study is the binding of the PX-FERM-like proteins to the GTPase Ras. Central to the relay of a cellular signal is the spatiotemporal organization of suitable signaling components, and the interplay between cellular localization and signaling, and in particular the role of endosomes in differential signaling mechanisms, has become a field of intense interest (21, 22). Furthermore, it is increasingly recognized that the cellular localization of Ras proteins at different organelles such as endosomes is critical for differential Ras-mediated signaling (23). Here we identified a trio of PX proteins that are endosome-associated and bind to H-Ras(GTP) via a unique FERM-like domain interaction. As H-Ras is highly similar to other Ras-family members, it is not yet possible to link PX-FERM-like proteins directly to a specific Ras protein functionally (30). It is interesting to speculate that other FERM domain proteins outside of the PX family will have similar binding activity. This is supported by the identification of Krit1 as an effector of Rap1, to stabilize junctional integrity in epithelial cells (31). Individually the Ras GTPase family and FERM domain-containing protein families play critical roles in many signaling cascades, so the demonstration of a direct association between these protein families would have important implications for our understanding of these processes.

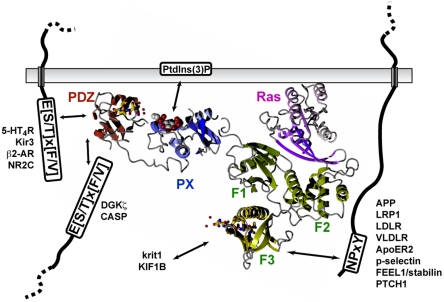

The precise mechanism of action of the PX-FERM-like proteins in endosomal trafficking and signaling still remains unknown. What is clear, though, is that these proteins are primed to act as membrane and receptor interaction scaffolds and can direct numerous molecular associations important for these processes. Our results, in combination with previous studies, allow us to propose a model for PX-FERM-like protein interactions at the endosomal membrane (Fig. 6). The proteins are directly coupled to endosomes via their PX domain, and it is likely that membrane association is further stabilized by other interactions through coincidence detection (32). The proteins once localized will then engage with receptors containing NPxY sorting motifs for endosomal to cell surface recycling, via binding to the PTB-related F3 module. SNX27 will in addition engage a separate subset of transmembrane cargo containing type-I PDZ motifs (E[S/T] × [F/V]) via the PDZ domain. Finally, the proteins can also associate with and recruit other molecules and cytosolic effectors, including Ras via the F1 module, and other PDZ motif and NPxY-containing soluble factors. Although Fig. 6 shows all known binding partners and effectors, it is clear that many other proteins with similar motifs will be potential interacting partners. In particular, a large number of receptor tyrosine kinases contain NPxY sorting signals and are therefore interesting candidates as PX-FERM-like cargo molecules (33).

Fig. 6.

A model for the network of interactions driven by the PX-FERM-like proteins. H-Ras (purple ribbons), NPxY peptide (gold cylinders), and Type-I PDZ-binding peptides (gold cylinders) were modeled onto the SNX27 SAXS-derived structure following structural alignment of respective complexes with PLC RA domain, FE65 PTB domain, and syntenin PDZ domain. The bound PI(3)P (spheres) is shown from our docking studies (Fig. 4E). The PX domain binds to PI(3)P, and the similarity of the F3 module of the FERM domain suggests it will be responsible for binding membrane and cytoplasmic NPxY-containing proteins. The similarity of the F1 module to RA domains suggests this region governs interaction with Ras. SNX27 possesses an additional N-terminal PDZ domain that binds cytosolic and transmembrane proteins via C-terminal type-I PDZ binding motifs, E[S/T] × [F/V]. Note that the FERM-like F2 module is expected to differ from the canonical F2 module depicted.

In summary, we have shown that SNX17, SNX27, and SNX31 belong to a subfamily of PX proteins, and our biochemical and structural studies present important details on the overall structure of PX-FERM-like proteins and the mechanisms by which they engage biological ligands. This provides the basis for future studies aimed at dissecting the role of these proteins in endosomal sorting, and the potential coupling of transport to downstream signaling outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Detailed methods are given in SI Text.

Molecular Biology and Protein Expression Expression.

cDNAs encoding human SNX17, SNX17-PX(1-110), mouse SNX27b (herein referred to as SNX27), SNX27ΔPDZ(156-526), and mouse SNX31 were expressed in Escherichia coli with N-terminal GST tags. SNX27, SNX27-PX(156-265), SNX17-PX, human H-Ras(1-166), and H-Ras(G12V)(1-166) were expressed with N-terminal His tags. A synthetic gene encoding an R36Q mutant of the SNX17-PX domain was synthesized by Genesearch and expressed with an N-terminal GST tag. Human SNX17 was cloned into pEGFP-N1 for expression in mammalian cells with a C-terminal GFP tag. SNX17(R36Q)-GFP was generated using the Quick change site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). Mouse SNX27 was cloned into pEGFP-C1 with an N-terminal GFP tag for mammalian cell expression.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry.

All ITC experiments were performed using a Microcal iTC200 instrument. APP peptides at 3 mM were titrated into 0.05 mM SNX17 and SNX27 proteins in 13 × 3.1 μL aliquots at 10 °C. Similarly, PIP head groups were titrated at 0.5 mM into 0.02 mM proteins in 13 × 3.1 μL aliquots at 25 °C.

H-Ras-Binding Assay.

GST-tagged SNX17, SNX17 PX domain, SNX27ΔPDZ, and SNX31 proteins were mixed with H-Ras(G12V) or H-Ras, bound to glutathione sepharose, washed, and then eluted in SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Western blot analysis was performed using mouse anti-Ras. For nucleotide dependency experiments, H-Ras was loaded with GTP or GDP by adding a 5-fold molar excess of EDTA and a 20-fold molar excess of GTP/GDP. Samples were incubated for 30 min at room temperature, reactions stopped with 100 mM MgCl2, and proteins purified by gel filtration.

SNX17 PX-Domain Crystal Structure Determination.

SNX17 PX domain was cleaved from GST using tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease, purified further by gel filtration (in 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT), then concentrated to 15 mg/mL. Crystals were grown by vapor diffusion in 0.1 M Tris (pH 8.0), 1.8 mM LiSO4. Data were collected at the University of Queensland Remote Op Crystallisation and X-ray (UQ ROCX) diffraction facility and integrated and scaled with d*TREK (34). The structure was solved by molecular replacement using PHASER (35) and automated model building with ARP/wARP (36). Refinement was done with PHENIX (37).

NMR Spectroscopy.

Samples of 15N/13C-labeled or 15N-labeled SNX17 PX domain were produced as described (38). The His tag was removed with TEV protease, then the protein was gel filtered into 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.0), 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT, and 10 mM Li2SO4 as required, and concentrated to 0.8 mM. All spectra were collected at 298 K on a Bruker 900-MHz spectrometer with cryoprobe and Z-axis gradients. Triple resonance experiments were performed in 10% D2O. Sequential backbone assignments were obtained by recording 3D HNCACB, CBCA(CO)NH, HNCO, and HN(CA)CO spectra. (H)CC(CO)NH-TOCSY and H(CC)(CO)NH-TOCSY experiments were used for side-chain assignments. All data were acquired using nonuniform sampling and processed using maximum entropy reconstruction (39, 40). For lipid binding experiments 15N HSQC spectra of SNX17 PX domain were recorded with increasing amounts of diC8-PI(3)P to a final molar ratio of 8∶1. Docking of the PI(3)P into the SNX17 PX-domain structure was done with HADDOCK using restraints derived from NMR experiments, as described in SI Text.

Indirect Immunoflourescence.

HeLa cells were transiently transfected with SNX17-GFP or GFP-SNX27 constructs using LipofectAMINE (Invitrogen). Cells were fixed and permeabilized before staining with appropriate primary and secondary antibodies for 1–2 h at room temperature. Monolayers were examined using a Zeiss LSM 510 META confocal fluorescent microscope.

SAXS Data Collection and Modeling.

SAXS data were collected at the Australian Synchrotron using four protein concentrations between 1.25 and 8.0 mg/mL. Scattering data were background-corrected, averaged, and scaled using SAXS15ID software. All further processing was carried out using the ATSAS programme suite (version 2.3) (http://www.embl-hamburg.de/biosaxs/software.html). Ab initio models were calculated using GASBOR, with a total of 20 independent simulations carried out for each protein, and averaged with DAMAVER. Rigid body modeling was performed using BUNCH.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We acknowledge support from the UQ ROCX facility and the Queensland NMR Network. Thanks to Kevin Jack and staff of the Australian Synchrotron for assistance with SAXS data collection, Jasmine Davis for protein expression, Natalie Castro for cellular localization studies, Rodrigo Morales for peptide purification, and Kirill Alexandrov for the H-Ras plasmid. We are grateful to David Owen, Andrew Whitten, and Kirill Alexandrov for critical reading. This work was supported by funds from the Australian Research Council (ARC) (DP0878608 and DP1095728) and National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) (511072). R.D.T. is supported by an NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship (511042). B.M.C. is supported by an ARC Future Fellowship (FT100100027).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. F.M.B. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

Data deposition: Coordinates and structure factors for the SNX17 PX domain have been deposited in the RCSB Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org/pdb/home/home.do (PDB ID code 3LUI). Raw diffraction images are available on the Diffraction Image Experiment Repository (DIMER) at http://xr-diffraction.imb.uq.edu.au. NMR assignments have been deposited in the Biological Magnetic Resonance Bank (http://www.bmrb.wisc.edu/) (BMRB accession number 17497).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1017110108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Cullen PJ. Endosomal sorting and signalling: An emerging role for sorting nexins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:574–582. doi: 10.1038/nrm2427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seet LF, Hong W. The Phox (PX) domain proteins and membrane traffic. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1761:878–896. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burden JJ, Sun XM, Garcia AB, Soutar AK. Sorting motifs in the intracellular domain of the low density lipoprotein receptor interact with a novel domain of sorting nexin-17. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:16237–16245. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313689200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stockinger W, et al. The PX-domain protein SNX17 interacts with members of the LDL receptor family and modulates endocytosis of the LDL receptor. EMBO J. 2002;21:4259–4267. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Kerkhof P, et al. Sorting nexin 17 facilitates LRP recycling in the early endosome. EMBO J. 2005;24:2851–2861. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knauth P, et al. Functions of sorting nexin 17 domains and recognition motif for P-selectin trafficking. J Mol Biol. 2005;347:813–825. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adachi H, Tsujimoto M. Adaptor protein sorting nexin 17 interacts with the scavenger receptor FEEL-1/stabilin-1 and modulates its expression on the cell surface. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1803:553–563. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Czubayko M, Knauth P, Schluter T, Florian V, Bohnensack R. Sorting nexin 17, a non-self-assembling and a PtdIns(3)P high class affinity protein, interacts with the cerebral cavernous malformation related protein KRIT1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;345:1264–1272. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.04.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seog DH, Han J. Sorting nexin 17 interacts directly with kinesin superfamily KIF1Bbeta protein. Korean J Physiol Pha. 2008;12:199–204. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2008.12.4.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee J, et al. Adaptor protein sorting nexin 17 regulates amyloid precursor protein trafficking and processing in the early endosomes. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:11501–11508. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800642200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andersen OM, Willnow TE. Lipoprotein receptors in Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:687–694. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bu G. Apolipoprotein E and its receptors in Alzheimer’s disease: Pathways, pathogenesis and therapy. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:333–344. doi: 10.1038/nrn2620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joubert L, et al. New sorting nexin (SNX27) and NHERF specifically interact with the 5-HT4a receptor splice variant: Roles in receptor targeting. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:5367–5379. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lunn ML, et al. A unique sorting nexin regulates trafficking of potassium channels via a PDZ domain interaction. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1249–1259. doi: 10.1038/nn1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lauffer BE, et al. SNX27 mediates PDZ-directed sorting from endosomes to the plasma membrane. J Cell Biol. 2010;190:565–574. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201004060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rincon E, et al. Proteomics identification of sorting nexin 27 as a diacylglycerol kinase zeta-associated protein: New diacylglycerol kinase roles in endocytic recycling. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:1073–1087. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700047-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cai L, Loo LS, Atlashkin V, Hanson BJ, Hong W. Deficiency of sorting nexin 27 (SNX27) leads to growth retardation and elevated levels of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor 2C (NR2C) Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:1734–1747. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01044-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacNeil AJ, Mansour M, Pohajdak B. Sorting nexin 27 interacts with the cytohesin associated scaffolding protein (CASP) in lymphocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;359:848–853. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.05.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng B, et al. Regulation of epidermal growth factor receptor degradation by heterotrimeric Galphas protein. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:5538–5550. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-06-0446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng B, et al. RGS-PX1, a GAP for GalphaS and sorting nexin in vesicular trafficking. Science. 2001;294:1939–1942. doi: 10.1126/science.1064757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scita G, Di Fiore PP. The endocytic matrix. Nature. 2010;463:464–473. doi: 10.1038/nature08910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sorkin A, von Zastrow M. Endocytosis and signalling: Intertwining molecular networks. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:609–622. doi: 10.1038/nrm2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fehrenbacher N, Bar-Sagi D, Philips M. Ras/MAPK signaling from endomembranes. Mol Oncol. 2009;3:297–307. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu A, et al. A clathrin-dependent pathway leads to KRas signaling on late endosomes en route to lysosomes. J Cell Biol. 2009;184:863–879. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200807186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chishti AH, et al. The FERM domain: A unique module involved in the linkage of cytoplasmic proteins to the membrane. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:281–282. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01237-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bunney TD, et al. Structural and mechanistic insights into ras association domains of phospholipase C epsilon. Mol Cell. 2006;21:495–507. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Radzimanowski J, et al. Structure of the intracellular domain of the amyloid precursor protein in complex with Fe65-PTB2. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:1134–1140. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pylypenko O, Lundmark R, Rasmuson E, Carlsson SR, Rak A. The PX-BAR membrane-remodeling unit of sorting nexin 9. EMBO J. 2007;26:4788–4800. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garcia-Alvarez B, et al. Structural determinants of integrin recognition by talin. Mol Cell. 2003;11:49–58. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00823-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Colicelli J. Human RAS superfamily proteins and related GTPases. Sci STKE. 2004;2004:RE13. doi: 10.1126/stke.2502004re13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Francalanci F, et al. Structural and functional differences between KRIT1A and KRIT1B isoforms: a framework for understanding CCM pathogenesis. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315:285–303. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Di Paolo G, De Camilli P. Phosphoinositides in cell regulation and membrane dynamics. Nature. 2006;443:651–657. doi: 10.1038/nature05185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith MJ, Hardy WR, Murphy JM, Jones N, Pawson T. Screening for PTB domain binding partners and ligand specificity using proteome-derived NPXY peptide arrays. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:8461–8474. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01491-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pflugrath JW. The finer things in X-ray diffraction data collection. Acta Crystallogr D. 1999;55:1718–1725. doi: 10.1107/s090744499900935x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCoy AJ, et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Langer G, Cohen SX, Lamzin VS, Perrakis A. Automated macromolecular model building for X-ray crystallography using ARP/wARP version 7. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1171–1179. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marley J, Lu M, Bracken C. A method for efficient isotopic labeling of recombinant proteins. J Biomol NMR. 2001;20:71–75. doi: 10.1023/a:1011254402785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mobli M, Maciejewski MW, Gryk MR, Hoch JC. Automatic maximum entropy spectral reconstruction in NMR. J Biomol NMR. 2007;39:133–139. doi: 10.1007/s10858-007-9180-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mobli M, Maciejewski MW, Gryk MR, Hoch JC. An automated tool for maximum entropy reconstruction of biomolecular NMR spectra. Nat Methods. 2007;4:467–468. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0607-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cole C, Barber JD, Barton GJ. The Jpred 3 secondary structure prediction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:W197–201. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gouet P, Courcelle E, Stuart DI, Metoz F. ESPript: Analysis of multiple sequence alignments in PostScript. Bioinformatics. 1999;15:305–308. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/15.4.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bravo J, et al. The crystal structure of the PX domain from p40(phox) bound to phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate. Mol Cell. 2001;8:829–839. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00372-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.