Abstract

Gene expression noise varies with genomic position and is a driving force in the evolution of chromosome organization. Nevertheless, position effects remain poorly characterized. Here, we present a systematic analysis of chromosomal position effects by characterizing single-cell gene expression from euchromatic positions spanning the length of a eukaryotic chromosome. We demonstrate that position affects gene expression by modulating the size of transcriptional bursts, rather than their frequency, and that the histone deacetylase Sir2 plays a role in this process across the chromosome.

Cells display considerable variability in gene expression due to fluctuations in the rates of gene activation, transcription, and translation. In eukaryotes, slow promoter kinetics can result in transcriptional bursting and high cell-to-cell variability (noise) in gene expression (1). This phenomenon has been linked to gene position through spatial variation in the recruitment and retention of transcription factors, nucleosomes, and chromatin remodeling complexes (2–6). However, high-throughput studies of endogenous gene expression in yeast have failed to provide strong support for this hypothesis (7,8), presumably due to the masking of position effects by gene- and promoter-specific variables.

To characterize chromosome position effects independently of gene- and promoter-specific variables, we integrated reporter cassettes at 128 different euchromatic loci along the length of chromosome III in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Fig. 1 a). We measured reporter expression driven by two promoters with contrasting architectures (9). The ADH1 promoter (PADH1) is a covered promoter where gene expression is facilitated by SAGA (10) and a consensus TATA-box occupied by nucleosomes (11). Both features are linked to high transcriptional noise (7,12). The ACT1 promoter (PACT1) has a contrasting open promoter architecture where nucleosome deposition is inhibited by the presence of a Poly(dA::dT) tract (9) and through Reb1-mediated DNA bending (13).

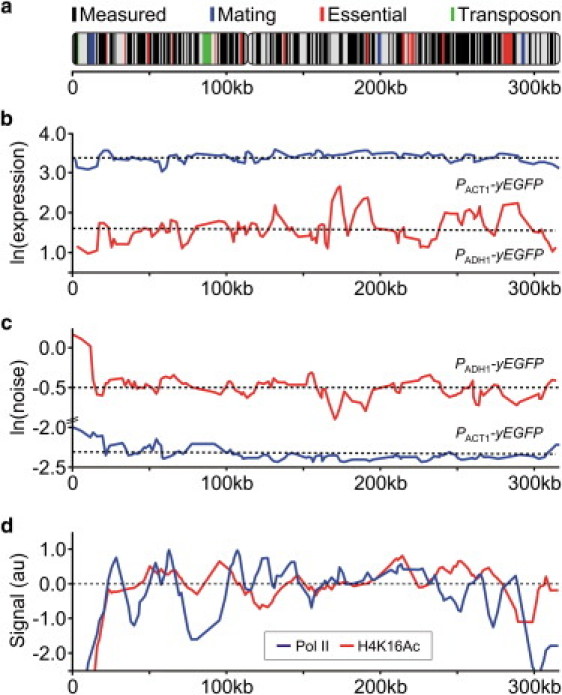

Figure 1.

Mapping position effects. (a) Position measured and chromosome III landmarks. (b) Population-average expression. (c) Relative standard deviation (noise). (d) Variation in polymerase II occupancy and H4K16 acetylation across chromosome III (see Supporting Material).

We quantified reporter gene expression by flow cytometry, and calculated the population-average expression and expression noise from measured fluorescence intensity distributions (see Supporting Material). For PADH1, the distribution was bimodal at two positions located between the heterochromatic regions at the left telomere and the silenced HML mating type locus (see Fig. S1 in the Supporting Material). A similar effect was recently observed when a fluoresent reporter gene was flanked by artificial Sir-mediated silencing gradients (14). For PACT1 at the same positions (Fig. S1), and at all other positions, the intensity distributions were unimodal. In the following, we focus on the unimodal expression distributions.

We observed that the average reporter expression and expression noise vary considerably across the chromosome for both promoters (Fig. 1, b and c). As expected, PADH1 is more sensitive to position effects than PACT1, and displays the highest variation in both expression level and expression noise. Nevertheless, expression noise is significantly correlated between the two promoters (p = 4 × 10−9, Table S1), suggesting that the observed position effects are linked to common, promoter-independent factors.

To identify these factors, we compared our data to polymerase II occupancy and histone modifications across chromosome III (Fig. 1 d, (15)). In this analysis, we mitigated potential effects of gene disruption by excluding experimental outliers and averaging over nearest-neighbor positions (see Supporting Material). We observed significant correlations between our data and regions depleted in polymerase II binding and acetylation of histone lysines H3K9, H3K14, and H4K16 (Table S1), targeted by the histone deacetylase Sir2 (16). Notably, expression noise is negatively correlated with polymerase binding (p = 5 × 10−8 for PACT1, p = 3 × 10−4 for PADH1) and H4K16 acetylation (p = 4 × 10−15 for PACT1, p = 2 × 10−15 for PADH1). Moreover, regions with low polymerase binding and high apparent Sir2 activity are robustly enriched in low expression and high noise positions (Fig. S2). As expected, these positions are predominantly located adjacent to heterochromatin.

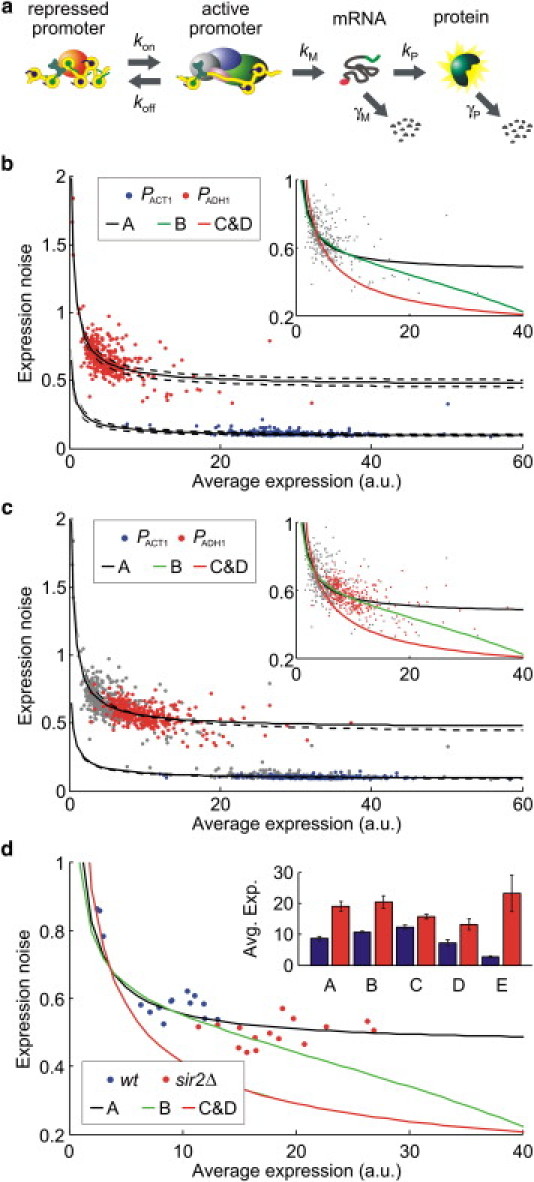

To gain insight into the mechanistic origin of chromosomal position effects, we analyzed a stochastic model of gene expression involving transitions between active and inactive promoter states and fluctuations in mRNA and protein abundances (Fig. 2 a). In this model, which is discussed in detail in (1), transcriptional burst size is defined by the ratio of the mRNA synthesis rate (kM) and the promoter deactivation rate (koff). Correspondingly, two different scenarios, variation in kM or in koff, involve modulation of burst size. We also consider a scenario where position effects arise from variation in burst frequency, which is determined by the promoter activation rate (kon), and a scenario where transcriptional bursting is absent. Since the four scenarios predict different dependencies of noise on average expression (see Supporting Material), we can use model discrimination techniques to determine which one best explains the experimental data.

Figure 2.

(a) Stochastic model defining position effects in terms of transcriptional bursting. Scenario A, B, and C corresponds to variation in kM, koff, and kon, respectively. Scenario D assumes no transcriptional bursting. (b) Full curves are fit to scenario A. Broken curves indicate the 95% confidence interval. Inset displays all fits to PADH1 data. (c) Full and broken curves show the fit of scenario A in the absence (gray) and presence (blue/red) of the nicotinamide, respectively. Inset displays all fits to PADH1 data. (d) PADH1 expression characterized for five loci in the presence (blue) and absence (red) of Sir2 (A: YCR020C; B: YCL030C; C: YCL037C; D: YCR060W; E: YCL064C). Inset shows the effect of Sir2 deletion on average expression.

The measured dependency of noise on average expression can be fitted well to variation in kM across the chromosome (r = 0.96 for PACT1 and r = 0.91 for PADH1, Fig. 2 b). For PADH1 (Fig. 2 b, inset), the experimental data is also explained reasonably well by variation in burst size through modulation of koff (Table S3). Indeed, variation in burst size (through kM or koff) explains the experimental data significantly better than variation in burst frequency (p = 6 × 10−5 for kM versus kon, and p = 0.02 for koff versus kon). In fact, the burst frequency scenario never performs better than that where transcriptional bursting is absent (Fig. 2 b, inset, Table S3). For PACT1, the four scenarios perform equally well, suggesting that its low expression noise is due to low transcriptional bursting.

To establish the involvement of Sir2, we quantified the impact of the Sir2 inhibitor, nicotinamide, on PADH1 and PACT1 expression across the chromosome (Fig. 2 c). As expected, nicotinamide had the greatest impact at positions associated with high Sir2 activity (Fig. S3). For PADH1 expression, the dependency of noise on average expression, measured in the presence of nicotinamide, is captured well by modulation of transcriptional burst size across the chromosome (Figs. 2 c and Fig. S5). As before, variation in burst size (through kM or koff) is significantly better at explaining the experimental data comparative variation in burst frequency (p = 3 × 10−37 for kM versus kon, and p = 4 × 10−46 for koff versus kon, Fig. 2 c).

We confirmed a role of Sir2 by characterizing the effect of Sir2 deletion on PADH1 expression at a position adjacent to the heterochromatic HML (YCL064C), and four other randomly chosen positions. The greatest effect was observed adjacent to the HML (Fig. 2 d). For all tested positions, the measured effect is captured by variation in burst size, but not by variation in burst frequency (p = 3 × 10−11 for kM versus kon, p = 10−22 for koff versus kon, Fig. 2 d). Interestingly, in these experiments, modulation of mRNA synthesis rates captures the data better than variation in promoter deactivation rates (p = 3 × 10−2).

Our finding that chromosomal position modulates burst size rather than frequency is consistent with previous studies of gene expression noise in mammalian cells using randomly integrated viral promoters (4,6). It is also consistent with the finding that the chromatin structure established by Sir2 is permissive to promoter activation, and suppresses mRNA synthesis by blocking a step downstream of transcription initiation (17). Indeed, our sir2Δ mutant data supports a model where Sir2 modulates the rate of mRNA synthesis differentially across the chromosome. However, the mechanisms involved in Sir2-mediated transcriptional repression remain controversial. Notably, PADH1 and PACT1 are strong promoters, and it is possible that Sir2 has more profound effects on the burst frequency of weak promoters. Additionally, whereas we observe significant Sir2-linked effects at most positons across the chromosome, the activity of Sir2 is typically viewed as being restricted to heterochromatic regions. This view has been challenged by systematic analysis documenting widespread binding of Sir2 across euchromatic genes, including ACT1 and ADH1 and other highly transcribed genes (18). Given our observations, it appears that Sir2 may play a more global role than previously anticipated.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Adam Rudner for useful discussions and Drs. Theodore Perkins and David Bickel for assistance with the statistical analysis.

This work was funded by Early Researcher Awards from the Ontario Government (to K.B. and M.K.), a scholarship from le Fonds Québécois de la Recherche sur la Nature et les Technologies to C.B., a grants from the Canadian Cancer Society to K.B. (grant No. 020309), the Canadian Institute of Health Research for M.K. (grant No. 079486), and the National Science and Engineering Research Council to M.K. (grant No. 313172-2005). K.B. is a Canada Research Chair in Chemical and Functional Genomics. M.K. is a Canada Research Chair in Systems Biology.

Supporting Material

References and Footnotes

- 1.Kaern M., Elston T.C., Collins J.J. Stochasticity in gene expression: from theories to phenotypes. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2005;6:451–464. doi: 10.1038/nrg1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Becskei A., Kaufmann B.B., van Oudenaarden A. Contributions of low molecule number and chromosomal positioning to stochastic gene expression. Nat. Genet. 2005;37:937–944. doi: 10.1038/ng1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Batada N.N., Hurst L.D. Evolution of chromosome organization driven by selection for reduced gene expression noise. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:945–949. doi: 10.1038/ng2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh A., Razooky B., Weinberger L.S. Transcriptional bursting from the HIV-1 promoter is a significant source of stochastic noise in HIV-1 gene expression. Biophys. J. 2010;98:L32–L34. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De S., Babu M.M. Genomic neighbourhood and the regulation of gene expression. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2010;22:326–333. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skupsky R., Burnett J.C., Arkin A.P. HIV promoter integration site primarily modulates transcriptional burst size rather than frequency. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2010;6:e1000952. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Newman J.R.S., Ghaemmaghami S., Weissman J.S. Single-cell proteomic analysis of S. cerevisiae reveals the architecture of biological noise. Nature. 2006;441:840–846. doi: 10.1038/nature04785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bar-Even A., Paulsson J., Barkai N. Noise in protein expression scales with natural protein abundance. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:636–643. doi: 10.1038/ng1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cairns B.R. The logic of chromatin architecture and remodelling at promoters. Nature. 2009;461:193–198. doi: 10.1038/nature08450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhaumik S.R., Green M.R. Differential requirement of SAGA components for recruitment of TATA-box-binding protein to promoters in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:7365–7371. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.21.7365-7371.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krogan N.J., Baetz K., Greenblatt J.F. Regulation of chromosome stability by the histone H2A variant Htz1, the Swr1 chromatin remodeling complex, and the histone acetyltransferase NuA4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:13513–13518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405753101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zenklusen D., Larson D.R., Singer R.H. Single-RNA counting reveals alternative modes of gene expression in yeast. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:1263–1271. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Angermayr M., Oechsner U., Bandlow W. Reb1p-dependent DNA bending effects nucleosome positioning and constitutive transcription at the yeast profilin promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:17918–17926. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301806200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelemen J.Z., Ratna P., Becskei A. Spatial epigenetic control of mono- and bistable gene expression. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000332. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu C.L., Kaplan T., Rando O.J. Single-nucleosome mapping of histone modifications in S. cerevisiae. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e328. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Imai S., Armstrong C.M., Guarente L. Transcriptional silencing and longevity protein Sir2 is an NAD-dependent histone deacetylase. Nature. 2000;403:795–800. doi: 10.1038/35001622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao L., Gross D.S. Sir2 silences gene transcription by targeting the transition between RNA polymerase II initiation and elongation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008;28:3979–3994. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00019-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsankov A.M., Brown C.R., Casolari J.M. Communication between levels of transcriptional control improves robustness and adaptivity. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2006;2:65. doi: 10.1038/msb4100106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.