Abstract

Background

Cholangiocarcinoma (CC) is a rare tumour with a dismal prognosis. As conventional medical management offers minimal survival benefit, surgery currently represents the only chance of cure. We evaluated DNA copy number (CN) alterations in CC to identify novel therapeutic targets.

Methods

DNA was extracted from 32 CC samples. Bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) array comparative genomic hybridization was performed using microarray slides containing 3400 BAC clones covering the whole human genome at distances of 1 Mb. Data were analysed within the R statistical environment.

Results

DNA CN gains (89 regions) occurred more frequently than DNA CN losses (55 regions). Six regions of gain were identified in all cases on chromosomes 16, 17, 19 and 22. Twenty regions were frequently gained on chromosomes 1, 5, 7, 9, 11, 12, 16, 17, 19, 20 and 21. The BAC clones covering ERBB2, MEK2 and PDGFB genes were gained in all cases. Regions covering MTOR, VEGFR 3, PDGFA, RAF1, VEGFA and EGFR genes were frequently gained.

Conclusions

We identified CN gains in the region of 11 useful molecular targets. Findings of variable gains in some regions in this and other studies support the argument for molecular stratification before treatment for CC so that treatment can be tailored to the individual patient.

Keywords: cholangiocarcinoma, comparative genomic hybridization, molecular targeted therapy, immunohistochemistry, DNA copy number change

Introduction

Cholangiocarcinoma (CC) is a relatively rare yet deadly tumour, with an annual incidence that almost equals its yearly mortality rate. The incidence of intrahepatic CC (ICC) has steadily increased worldwide over recent decades from, for example, 0.11 to 1.33 per 100 000 men in England and Wales during 1971–2001. This increase in incidence is paralleled with a concomitant rise in mortality rates, with age-standardized mortality rates increasing from 0.20 to 0.83 per 100 000 men in England and Wales during the same period, a trend mirrored worldwide.1–4 Intrahepatic CC now represents the commonest primary liver cancer among women in the UK, and the second commonest worldwide.3

The outlook once diagnosed with CC is dismal, with an overall 5-year survival of 3%.5 However, this improves to 15–67% following resection for ICC6–12 and to 23–62% in extrahepatic CC (ECC).6,13–16 At present there is no proven survival benefit with adjuvant chemotherapy following R0 resection.17–19

There is a lack of evidence for any substantial benefit of chemotherapy in palliative treatment. A recent Phase III trial showed a survival benefit of 3.6 months with gemcitabine and cisplatin vs. gemcitabine alone (median survival: 11.7 vs. 8.1 months).20 Despite this benefit with conventional chemotherapy, survival rates are still disappointingly poor. The majority of cases are unresectable: for example, a recent case series reported that 86.2% of ICC and perihilar CC (PHCC) cases were unresectable at presentation.21 It is well established that effective medical treatment makes it possible to downstage inoperable colorectal liver metastases and subsequently perform curative resections.22 There is an urgent need to find new effective treatments for CC in order to downstage inoperable cases so that curative resection can be offered. Targeted cancer therapies used either as neoadjuvant agents to downstage disease or in the adjuvant setting to prevent relapse represent an attractive option in CC. There is, however, a paucity of identified targets for known molecular agents in CC. We have therefore utilized a genome-wide technique in order to identify novel molecular targets in CC.

Comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) is a method of scanning the whole genome for DNA copy number (CN) alterations. This technique identifies regions of DNA gain and loss, and is especially useful in studying tumours.23 The amplification (gain of several DNA copies) of oncogenes and deletion of tumour suppressor genes are hallmarks of cancer and represent a key mechanism of tumourigenesis. Identifying CN gain of key target genes has proven significant in cancer treatment. For example, in breast cancer ErbB2 overexpression is caused by ERBB2 gene amplification in >90% of cases and improved survival can be achieved in these patients using targeted therapy (trastuzumab).24 In CGH, tumour and normal DNA are differentially labelled with fluorescence dyes (tumour DNA Cy3, reference DNA Cy5) and are then co-hybridized to metaphase spreads of chromosomes. Hybridization of repetitive sequences is blocked using human Cot-1 DNA. Reference and tumour DNA hybridize in a competitive manner with their complementary sequences on the metaphase chromosomes. The fluorescence of reference DNA and tumour DNA binding to each chromosome are then measured and quantified. The relative amounts of hybridized reference and tumour DNA reflect the CN of genomic regions. A fluorescence ratio in favour of Cy3 (tumour) reflects a CN gain, whereas a ratio in favour of Cy5 (reference DNA) reflects a CN loss. The location of the CN alteration is mapped to the physical location on the chromosome.25 However, the use of metaphase spreads is technically challenging and allows the identification of CN changes at a relatively low resolution of 5–10 Mb.26 Vast advances have been achieved in CGH methodology over the last decade, which has progressed from conventional metaphase CGH to array CGH, which uses DNA microarrays instead of human metaphase chromosome spreads.27 DNA fragments such as large-insert clones like bacterial artificial chromosomes (BACs) or oligo-nucleotides, which represent the human genome, are immobilized onto glass slides.27–29 The advantage of array CGH is that it vastly improves resolution from 1 Mb to 50 kb. Furthermore, it is faster and does not require cytogenetic expertise. In this study, we used array CGH to identify CN alterations with specific reference to known molecular targets.

Materials and methods

Tissue samples

Tissue was obtained from the Hammersmith Biological Resource Centre, a research tissue bank approved by the National Research Ethics Service (NRES). In total, 40 CC samples were obtained between 2003 and 2009. Intrahepatic, perihilar and extrahepatic CCs were included in the study. Gallbladder and ampullary carcinomas were excluded. Intrahepatic CCs are located within the liver parenchyma down to the second-order bile ducts; PHCCs occur in the left and right hepatic ducts to the origin of the cystic duct and ECCs may occur in the common bile duct down to, but not including, the ampulla.30 All cases were adenocarcinoma. Age, sex, survival and histopathological characteristics were recorded for all cases.

DNA extraction and quality assessment

A tissue section adjacent to that used for DNA extraction was stained with haematoxylin and eosin and the presence of tumour epithelium was verified by a histopathologist (GS) and the diagnosis confirmed. A 10-µm section of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue was used for DNA extraction. The FFPE section was macroscopically dissected to enrich for tumour cells, deparaffinized in xylene and then ethanol, and incubated overnight at 37 °C with sodium thiocyanate. DNA extraction was performed according to the Qiagen QIAmp DNA Microkit standard protocol (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA, USA) using proteinase K digestion. DNA was quantified using the NanoDrop spectrophotometer (ND-2000; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). To ensure that the DNA was of the quality required for use in array CGH experiments, a gene-specific, multiplex-size polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was used.31 Only cases with amplification products of ≥300 bp were deemed to be of sufficient quality for array CGH analysis.

Array comparative genomic hybridization

Bacterial artificial chromosome arrays containing the Sanger 1-Mb BAC array clone set, which comprises approximately 3400 BAC clones covering the whole human genome in distances of 1 Mb, were used.28 BAC clones were spotted on amino-active glass slides in triplicate (CodeLink; GE Healthcare Ltd, Chalfont St Giles, UK).

For each experiment, 525 ng of tumour DNA and 525 ng of reference DNA (Promega GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) were labelled with Cy3-dCTP and Cy5-dCTP, respectively (Amersham CyScribe Kit; GE Healthcare Ltd). Reference DNA was sex-mismatched to the tumour sample to provide an internal hybridization control. Each sample was mixed with 35 µl of random nonamer and 35 µl of reaction buffer and then incubated at 95 °C. Following this, the samples were put on ice for 5 min, after which 28 µl dCTP labelling mix, 10.5 µl Cy3/5-dCTP and 3.5 µl Klenow (ExoFree) enzyme were added to the mixture, which was incubated overnight at 37 °C. The labelled DNA was purified using spin-filter columns (Microcon; Millipore Corp., Billerica, MA, USA). The yield of labelled DNA and incorporation of fluorescence dye were determined using the NanoDrop spectrophotometer. Test and reference DNA were combined with 50 µg cot-1 DNA (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA, USA), 26 µl 10X blocking agent (Agilent Technologies UK Ltd, Wokingham, UK) and 130 µl 2X hybridization buffer (Agilent Technologies UK Ltd), denatured at 95 °C for 3 min and then pre-hybridized for 30 min at 37 °C. Samples were hybridized for 60 h at 60 °C at a rotation speed of 20 rpm. Slides were washed at room temperature with Agilent Oligo aCGH Wash Buffer 1 for 5 min and with Agilent Oligo aCGH Wash Buffer 2 for 1 min and subsequently scanned at a resolution of 5 µm using a microarray scanner (Agilent Technologies UK Ltd).

Data analysis

Fluorescence intensities were extracted using the array analysis software maia (Institute Curie, Paris, France) and the resulting text files imported into R.32 The log 2 ratios were normalized using the R package manor,33 using default parameters (exclusion of data points with a replicate deviation of >0.1 and/or a foreground : background signal ratio of <3). Normalized profiles were segmented using a circular binary segmentation (CBS; R package DNAcopy) algorithm34 and called using the CGHcall algorithm.35 Called CN profiles were converted into CN regions using the R package CGHregions36 and the percentage of cases within a group showing CN alterations was determined by assessing frequency plots of CN alterations.

ErbB2 protein expression

To verify ErbB2 CN gains identified by array CGH, ErbB2 protein expression was assessed in a subset of 19 cases by immunohistochemistry (IHC). The I-VIEW DAB Detection Kit (catalogue no. 760-091; Ventana Medical Systems, Inc., Tucson, AZ, USA) was used with standard dilutions using the Benchmark XT. Cases were scored by a histopathologist (GS) using the ToGA Trial criteria for grading gastric adenocarcinoma (+1, +2, +3).37,38

Results

Clinical data

DNA was extracted from 40 cases, 32 of which passed quality assessment by size PCR and were analysed for CN changes by aCGH. These included seven cases of ICC, 13 of PHCC and 12 of ECC. Clinicopathological data for the 32 cases are listed in Table 1. Twenty-three samples were from resection specimens and nine were from biopsies (non-resections). All patients received chemotherapy, either postoperatively or after diagnosis in the non-operative group. Mean patient age at diagnosis was 60.8 years (range: 25–77 years). Survival data were available for all except three cases, which were lost to follow-up at 1, 4 and 11 months, respectively, giving an overall mean follow-up of 12.5 months (range: 1–79 months). Overall survival from diagnosis differed significantly between the resection and non-resection groups (23 months vs. 9 months; P = 0.009, Gehan–Breslow–Wilcoxon test).

Table 1.

Clinicopathological data for the 32 cases analysed in the current study

| Age, years/sex | Location | Survival, months | Operation/procedure | Differentiation | T | R | Vascular invasion | Perineural invasion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resection group | ||||||||

| 69/F | ICC | 43 (A) | Extended right hepatectomy | Moderate | pT3 N1 | 1 | No | No |

| 64/F | ICC | 46 (A) | Left hepatectomy, excision of biliary tree | Moderate | pT1 N1 | 1 | No | No |

| 58/M | ICC | 15 | Wedge resection, RFA | Moderate | 2 | No | Yes | |

| 25/M | ICC | 23 | Left lateral segmentectomy, RFA | Poor | pT2 N0 | 2 | No | No |

| 71/F | PHCC | 1 (LTF) | Left hepatectomy, excision of biliary tree | Moderate | pT2 N0 | 1 | No | Yes |

| 53/M | PHCC | 12 | Right hepatectomy, excision of biliary tree | Poor | pT2 N1 | 0 | No | Yes |

| 67/M | PHCC | 48 | Right hepatectomy, excision of biliary tree | Good–moderate | pT2 N0 | 0 | No | No |

| 76/F | PHCC | 8 | Right hepatectomy | Moderate | pT2 Nx | 1 | No | No |

| 69/M | PHCC | 1 | Left hepatectomy | Moderate | pT2 N0 | 1 | No | No |

| 60/M | PHCC | 11 (A) | Right hepatectomy, excision of biliary tree | Moderate–poor | pT3 N1 | 1 | No | Yes |

| 57/M | PHCC | 13 | Extended right hepatectomy, excision of biliary tree | Poor | pT3 N1 | 1 | No | Yes |

| 73/M | PHCC | 7 (A) | Extended right hepatectomy | Moderate | pT3 N1 | 1 | No | No |

| 39/F | PHCC | 14 (A) | Left hepatectomy, RFA | 2 | No | No | ||

| 72/M | ECC | 10 | Excision of biliary tree | Moderate–poor | pT2 N1 | 1 | Yes | Yes |

| 46/M | ECC | 20 (A) | Pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy | Poor | pT3 N1 | 0 | Yes | Yes |

| 77/M | ECC | 10 | Excision of biliary tree | Poor | pT2 N0 | 1 | No | No |

| 57/M | ECC | 37 (A) | Excision of biliary tree | Moderate–poor | pT3 Nx | 2 | Yes | Yes |

| 67/F | ECC | 27 | Excision of biliary tree, distal gastrectomy | Good–moderate | pT4 N0 | 2 | No | No |

| 68/M | ECC | 22 | Pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy | Well | pT3 N0 | 2 | No | No |

| 63/M | ECC | 26 | Excision of biliary tree | pT1 N0 | 1 | No | Yes | |

| 73/M | ECC | 12 | Excision of biliary tree | pT3 N0 | 0 | No | Yes | |

| 56/M | ECC | 25 | Excision of biliary tree | Moderate | pT3 N1 | 1 | Yes | Yes |

| 52/M | ECC | 11 (LTF) | Excision of biliary tree | Moderate–poor | pT2 N1 | 1 | No | Yes |

| Non-resection group | ||||||||

| 38/M | ICC | 4 (LTF) | Laparotomy, RFA (segments II, III, IV, V), tumour biopsy, absolute alcohol injection to segment V liver lesion | Poor | – | – | – | – |

| 68/F | ICC | 1 | Biopsy | – | – | – | – | – |

| 60/M | ICC | 25 | Biopsy | – | – | – | – | – |

| 72/F | PHCC | 2 | Biopsy | Poor | – | – | No | No |

| 57/F | PHCC | 79 | Palliative bypass | Poor | – | – | – | – |

| 73/M | PHCC | 3 | Biopsy | – | – | – | No | No |

| 47/M | PHCC | 9 | Biopsy | – | – | – | – | Yes |

| 62/M | ECC | 10 | Biopsy | – | – | – | – | – |

| 56/M | ECC | 14 | Palliative bypass | Moderate | – | – | – | – |

M, male; F, female; ICC, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; ECC, extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; PHCC, perhilar cholangiocarcinoma; A, alive; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; LTF, lost to follow-up

Copy number alterations

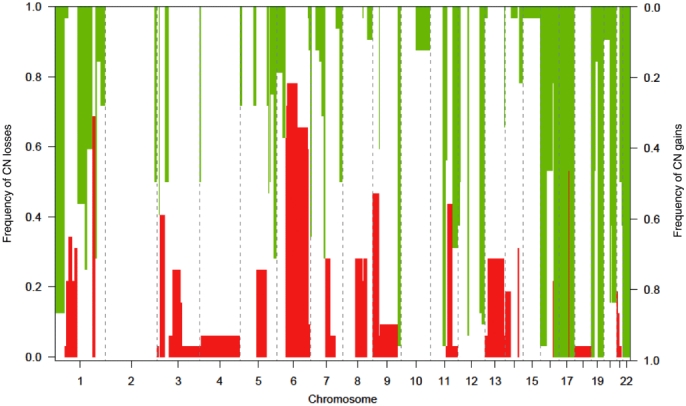

All cases revealed CN alterations. DNA CN gains occurred more frequently than DNA CN losses overall (Fig. 1), with 89 regions of CN gain and 55 regions of CN loss. Six regions of gain were identified in all cases at: 16q21→24.2; 17p13.3→q21.32; 17q22→24.1; 17q24.3→25.3; 19p13.3→13.11; 19q13.12→13.43, and 22q11.1→13.33. A further 29 regions of gain appeared frequently (in >20 cases) on chromosomes 1, 5, 7, 9, 11, 12, 16, 17, 19, 20 and 21 (Table 2), whereas CN losses were much less frequent (Table 3). No region was lost in all cases. The overall frequency of gains and losses was lower in the ECC group. There was no association of groups defined by unsupervised hierarchical clustering with differentiation, perineural or vascular invasion.

Figure 1.

DNA copy number (CN) alterations in all cases showing regions of gain and loss

Table 2.

Regions with frequent copy number gain

| Chromosome | Chromosomal regions | Clones, n | Cases, n |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | p13.3→p21 | 53 | 28 |

| 1 | q21.1→21.3 | 11 | 24 |

| 1 | q31.3→32.1 | 8 | 23 |

| 5 | q34→35.3 | 14 | 23 |

| 7 | p22.1→22.3 | 10 | 21 |

| 7 | q11.21→11.22 | 9 | 23 |

| 7 | q11.23 | 4 | 25 |

| 7 | q22.1 | 7 | 26 |

| 9 | q33.3→34.3 | 16 | 30 |

| 11 | q12.2→13.4 | 19 | 30 |

| 11 | q23.1→25 | 30 | 22 |

| 12 | p13.31→13.33 | 12 | 20 |

| 12 | q13.11→13.2 | 15 | 30 |

| 12 | q23.3→24.23 | 12 | 28 |

| 12 | q24.23→24.33 | 18 | 29 |

| 16 | p13.3→11.2 | 34 | 31 |

| 16 | q21→24.2 | 32 | 32 |

| 17 | p13.3→q21.32 | 71 | 32 |

| 17 | q22→24.1 | 15 | 32 |

| 17 | q24.2→24.3 | 4 | 29 |

| 17 | q24.3→25.3 | 13 | 32 |

| 19 | p13.3→13.11 | 24 | 32 |

| 19 | q13.11→13.12 | 4 | 26 |

| 19 | q13.12→13.43 | 32 | 32 |

| 20 | q11.21→11.23 | 14 | 27 |

| 20 | q11.23→12 | 5 | 20 |

| 20 | q13.11→13.33 | 32 | 27 |

| 21 | q22.2→22.3 | 4 | 20 |

| 22 | q11.1→13.33 | 53 | 32 |

Table 3.

Regions with frequent copy number loss

| Chromosome | Chromosomal regions | Clones, n | Cases, n |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | q25.3→35.2 | 14 | 22 |

| 6 | p12.3 | 4 | 20 |

| 6 | p25.3→12.1 | 4 | 23 |

| 6 | p12.1→q16.3 | 47 | 25 |

| 6 | q21→25.2 | 51 | 21 |

| 17 | q21.3→22 | 4 | 22 |

Genes for novel potential therapeutic targets

Candidate genes were identified from the Ensembl database (http://www.ensembl.org) and a literature search of known amplified oncogenes in human cancers with established and promising agents for molecular targeting.39 Several genes of interest were identified within the altered regions (Table 4). The BAC clones covering the genes ERBB2, MEK2 and PDGFB were gained in all cases. Regions covering the genes MTOR, VEGFR 3, PDGFA, RAF1, VEGFA and EGFR were frequently gained in 28, 23, 21, 19, 12 and 10 cases, respectively. FLT3 and MEK1 were each gained in one case. Gain of the region covering VEGFA and EGFR did not demonstrate a survival disadvantage.

Table 4.

Genes of interest identified within the altered regions

| Target | Chromosome | Cases, n |

|---|---|---|

| ERRB2 (NEU, HER-2, CD340) | 17q11.2–q12 | 32 |

| MEK2 (MAP2K2) | 19p13.3 | 32 |

| PDGFB (SSV) | 22q13.1 | 32 |

| MTOR (RAFT1, RAPT1, FLJ44809) | 1p36.22 | 28 |

| VEGFR 3 (FLT4, PCL) | 5q34–q35 | 23 |

| PDGFA (PDGF1) | 7p22.3 | 21 |

| RAF1 (c-Raf) | 3p25.1 | 19 |

| VEGFA (VPF) | 6p12 | 12 |

| EGFR (ERBB1) | 7p12 | 10 |

| FLT3 (CD135, STK1, FLK2) | 13q12.2 | 1 |

| MEK1 (MAP2K1, MAPKK1) | 15q22.1–q22.33 | 1 |

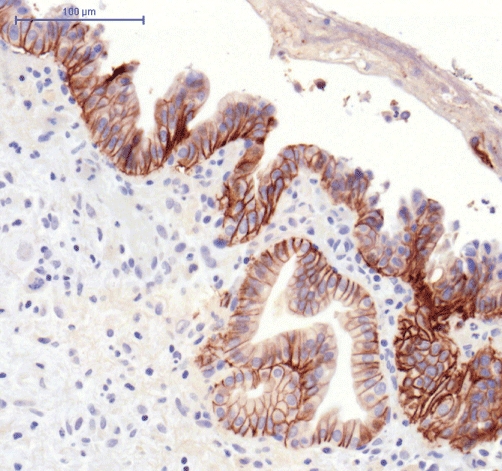

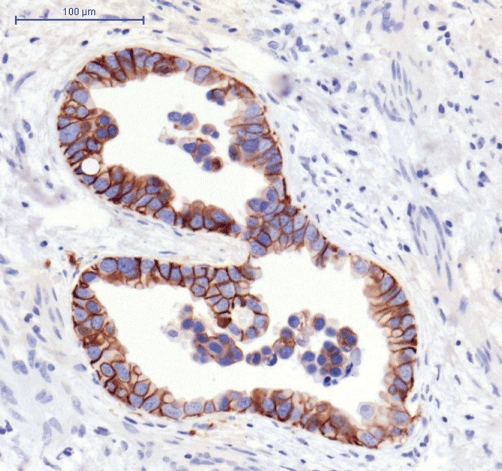

ErbB2 protein expression

ErbB2 expression was heterogeneous throughout the tumour tissue, with some areas showing strong expression and others in the same tumour section showing none (Figs 2 and 3). Overall, 19 cases were positive, of which 10 were scored as +2 and one as +3.

Figure 2.

ErbB2 expression using immunohistochemistry

Figure 3.

ErbB2 expression using immunohistochemistry

Discussion

Recent advances in targeted cancer therapies, particularly in the development of monoclonal antibodies (MAb) and tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), have brought about significant changes in oncology practice. There has been a surge in the development of such agents, many of which have now been licensed for clinical use in a variety of tumours, and dozens of further agents are in the pipeline at various stages of development. Because of the disappointing effectiveness of conventional chemotherapy in CC, targeted cancer therapies represent an appealing potential treatment option for this resistant tumour. To date, however, no targeted agent has been effectively tested and licensed for clinical use for CC. Experience gained with other tumour types suggests that considerable heterogeneity exists amongst tumours of the same pathological type in the same tissue. Therefore, blind treatment of all CCs may lead to a less efficient response in many patients when targeted treatments are used. As experience in breast cancer using trastuzumab has already shown, pre-screening of the patient population to identify those who express the target can potentially lead to the identification of those patients who will benefit most from these expensive treatments.

This is the first UK study of CC using array CGH. We employed a genome-wide technique assessing DNA CN alterations in 32 UK cases of CC. We identified 89 regions of CN gain and 55 regions of CN loss in CC. Frequent CN gains were identified on chromosomes 1, 5, 7, 9, 11, 12, 16, 17, 19, 20, 21 and 22. Copy number losses were much less frequent. Eleven genes of interest in CC for targeted cancer therapies with proven efficacy in other cancers were identified (Tables 4 and 5). At present, targeted agents in CC have been trialled at Phase I/II, apart from cediranib, for which a Phase II/III trial has recently started recruitment.

Table 5.

Therapies currently licensed or in trial in other malignancies relevant to the targets identified in this study

| Agent | Alternative names | Target | Licensed | Tumours |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARRY-438162 | MEK 162 | MEK (1/2) inhibitor | Phase I | Multiple ST |

| Bevacizumab | Avastin | VEGFA | Yes | CRC |

| Cediranib | Recentin, AZD2171 | Pan VEGFR TK, PDGFB, cKIT | Phase III | CRC |

| Cetuximab | Erbitux | EGFR | Yes | CRC |

| Erlotinib | Tarceva | EGFR TK | Yes | Pancreatic |

| Everolimus | RAD001, Afinitor | MTOR | Yes | RCC |

| Lapatinib | Tyverb | EGFR and ERBB2 TKs | Yes | Breast |

| Lonafarnib | SCH66336, Sarasar | Farnesyl-OH-transferase inhibitor interferes with the RAS/RAF/MAPK pathway. Targets the level of H-Ras; does not inhibit the functional activity of K-Ras and N-Ras | Phase III | NSCLC |

| Panitumumab | ABX-EGF, Vectibix | EGFR | Yes | CRC |

| Sorafenib | Nexavar, BAY 43-9006 | RAF/MEK/ERK pathway at the level of Raf kinase, VEGFR-2, VEGFR-3 and PDGFR-β | Yes | RCC |

| Sunitinib | Sutent, SU11248 | Multiple receptor TKVEGFR-1, VEGFR-2, FLT3, cKIT, PDGFR-α | Yes | RCC, GIST |

| Trastazumab | Herceptin | ERBB2 | Yes | Breast |

| Vandetanib | Zactima, ZD6474 | TK vs.VEGFR-2, EGFR and RET | Phase III | NSCLS |

TK, tyrosine kinase; CRC, colorectal cancer; ST, solid tumour; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; GIST, gastrointestinal stromal tumour

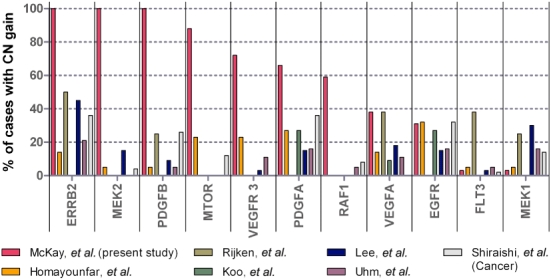

Studies of CC to date have shown widely variable expression profiles for many molecular targets in CC. The region encoding ERBB2 at 17q12 was gained in all cases of CC in our study. In breast cancer, there are high levels of concordance (97%) between ErbB2 gain identified by array CGH and protein overexpression.40 There is also a well-established scoring system for protein overexpression demonstrated by IHC in breast cancer, which is related to predicted treatment response to trastuzumab. Data from the ToGA Trial in gastric cancer, however, demonstrated that the standard breast cancer scoring system was insufficient for gastric malignancies because of the difference in heterogeneity between gastric cancer and breast tumours.37,38 Thus, a gastric cancer scoring system was proposed and validated by a consensus panel to allow for incomplete staining and tissue heterogeneity. The gastric cancer scoring system allots scores of +2 and +3 for weak to moderate, and moderate to strong, complete or basolateral staining in >10% of tumour cells, respectively. Cholangiocarcinomas, like gastric cancers, are heterogeneous tumours with prolific stromal components and therefore the gastric cancer scoring system was adopted for this study. Surprisingly, although ErbB2 was gained in all our cases, this only translated to 58% (11/19) of cases with +2/+3 IHC positivity. Interestingly, some areas of tumour demonstrated strong ErbB2 staining, whereas other areas within the same tumour were negative. This suggests that the standard breast cancer scoring system for ErbB2 IHC would be inadequate for assessing those likely to benefit from trastuzumab therapy, and the gastric cancer system may be significantly better. Further studies are required to validate this. It also suggests that, although ErbB2 was gained at a DNA level in all cases in this study, there is a further level of control of expression at a transcriptomic or proteomic level. Our findings are supported by the widely variable data from other studies of ErbB2 in CC, in which gene amplification is reported in 2–100% of cases41–45 and protein overexpression varies from none to 80%.41–58 Other CGH studies using metaphase chromosome CGH have identified CN gain in the same region in only 0–50% of cases (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Copy number (CN) gain of molecular targets in other comparative genomic hybridization studies

To date, there have been several CGH studies of CC, but only six have published regions of CN alteration (Table 6).59–66 These studies used metaphase chromosome CGH, a less robust technique with reduced resolution, to report gained and lost chromosomal regions. As the chromosomal locations of each of the altered genes reported in this study are known, the altered gene regions can be compared between studies for each target (Fig. 4). Previous CGH studies of CC have been performed in a variety of different populations, including in Germany, the USA, South Korea and Japan. Differing aetiological factors may have contributed to the different CN profiles observed. For example, in eastern Asia (China, Korea, Thailand, Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia) liver flukes are endemic: approximately 1.8 million people are infected with Clonorchis sinensis in Korea67 and 36.4% of the population are infected with Opisthorchis viverrini in northeast Thailand.68 Liver fluke infection accounts for the high rates of CC in eastern Asia: for example, in Khon Kaen, Thailand, the age-standardized incidence rate of primary liver cancer in men is 90.0 per 100 000 person-years and 89% of cases are CC.69 However, outside eastern Asia, liver flukes are rare and other aetiological factors play key roles. In Japan, 9% of cases are associated with hepatolithiasis, which is a rare phenomenon in Western countries.70 Furthermore, gene expression profiles of CC associated with liver fluke in Thailand and CC not associated with liver fluke in Japan revealed distinct differences in gene expression, with Thai CC associated with the upregulation of genes involved in the xenobiotic metabolism, and Japanese CC associated with the upregulation of genes related to growth factor signalling.71 In the USA and Europe, obesity is a recognized risk factor for CC.72 Overall, 68% of the adult population in the USA and Europe is overweight or obese, and almost 26% and 24% of women are obese in the USA and the UK, respectively.73,74 In comparison, the incidence of obesity in eastern Asia is low. The worldwide variation in risk factors for CC may explain the genetic variability of CN target gains between studies and strengthens the need for molecular stratification before treatment.

Table 6.

Comparative genomic hybridization studies reporting regions of copy number alterations in cholangiocarcinoma

| Study | Year | Cases, n | CC type | Country | Technique |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homayounfar et al.59 | 2009 | 22 | 22 ICC | Germany | Metaphase CGH |

| Rijken et al.60 | 1999 | 14 | 14 ECC | USA | Metaphase CGH |

| Koo et al.61 | 2001 | 11 | 11 ICC | South Korea | Metaphase CGH |

| Lee et al.62 | 2004 | 33 | 33 ICC | South Korea | Metaphase CGH |

| Uhm et al.63 | 2005 | 19 | 19 ICC | South Korea | Metaphase CGH |

| Shiraishi et al.64a | 2001 | 50 | 8 ICC, 9 PHCC, 16 ECC, 17 GB | Japan | Metaphase CGH |

Several small Phase II trials have been performed in CC with targeted cancer therapy; however, to date, their outcomes have been disappointing. Lapatinib is an orally administered agent that targets EGFR and ErbB2 tyrosine kinases. It is licensed in the UK for the treatment of breast cancer in combination with capecitabine.75 A Phase II trial involving 17 patients with biliary tree cancers demonstrated poor results, with a median progression-free survival of 1.8 months, overall survival of 5.2 months, and no objective responses when using lapatinib as a single agent.76 EGFR expression was measured in only two cases (both positive), but ErbB2 expression was not measured. We found that ERBB2 was gained in all our cases and EGFR was gained in 10 cases (31%). It is possible that EGFR and/or ERBB2 were not overexpressed in the majority of cases in the trial population, which would account for the poor outcome in the trial.

Erlotinib is an EGFR TKI licensed for the treatment of pancreatic and non-small cell lung cancer in combination with conventional chemotherapy. The first Phase II trial treating CC patients with erlotinib was published in 2006.77 Forty-two patients were treated daily with erlotinib monotherapy. The median time to disease progression was 2.4 months and median overall survival was 7.5 months. Overexpression of EGFR was assessed by IHC in 36 patients, for 81% of whom findings were positive (1+ to 3+). EGFR status did not correlate significantly with clinical outcome. Our study failed to demonstrate a correlation between EFGR gain and survival.

Bevacizumab is an i.v. administered MAb that inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEFG-A). In the UK it is licensed for the treatment of colorectal cancer, breast cancer, renal cell carcinoma and non-small cell lung cancer in combination with conventional chemotherapy. A recently completed single-arm Phase II trial treating 35 CC patients with gemcitabine, oxaliplatin and bevacizumab has shown promising results.78 Median progression-free survival was 7 months, overall survival was 12.7 months and the objective response rate was 40%. There are currently four further Phase II studies investigating the effect of bevacizumab on patients with CC. A more recent multicentre Phase II trial recruited 53 patients for treatment with erlotinib and bevacizumab.79 Median overall survival was 9.9 months and median time to disease progression was 4.4 months. This trial investigated EGFR mutation and serum VEGF; serum levels in 26 patients had no significant relation to outcome. VEGFA was gained in 12 cases (38%) in our study, and bevacizumab appears to be a promising agent in combination with conventional chemotherapeutic agents for these cases.

Cediranib (Recentin, AZD2171) is an orally administered TKI targeting all three VEGFRs (VEGFR-1, -2 and -3), cKIT, PDGFRA and PDGFRB.80 The ABC-03 Trial is a randomized Phase II/III trial designed to compare cediranib or placebo in combination with cisplatin/gemcitabine in subjects with advanced biliary tract cancers.81 It is currently recruiting patients. Our data show that a high percentage of CC patients exhibited gains in regions encoding for VEGFR2, VEGFR3, PDGFA and PDGFB. In this setting, cediranib may represent a potentially effective agent. In reference to the CN profiles identified in our study, cediranib represents an appealing potential treatment option.

The diverging incidences of ICC and ECC suggest possible differences in the molecular pathogenesis of CC at different anatomical sites and, consequently, expression of different molecular targets. Fewer gains and considerably fewer losses were observed in ECC compared with ICC and PHCC. However, these differences were not statistically significant enough to be used as a tool for pre-screening the population prior to targeted therapy based on anatomical subtypes. A recent prospective, multicentre pilot study included 66 patients with a variety of malignant diseases refractory to treatment, who underwent molecular stratification by IHC, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and limited gene expression profiling (51 genes) for molecular targets with established targeted agents.82 Treatment was chosen based on the individual's expression of molecular targets and compared with progression-free survival on his or her previous regime. Eighteen of 66 patients showed improvements in progression-free survival following molecular profiling-driven treatment choices (9.7 vs. 5.0 months), which suggests a promising method for molecular stratification of CC patients.

Cholangiocarcinoma remains a challenging malignancy to treat. We have identified 11 targets, eight of which were variably gained. The variable gain of molecular targets in this and other studies supports the argument for molecular stratification before treatment for this complex malignancy. Molecular stratification enables treatment to be tailored to the individual patient with the aim of improving outcome. A multitude of regimes comprising conventional and/or targeted agents have and are being trialled. Monotherapy with targeted agents has yielded disappointing results to date and there is an urgent need to investigate targeted agents used in combination therapy with conventional chemotherapeutic agents in molecularly screened populations.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Shaib Y, El-Serag HB. The epidemiology of cholangiocarcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2004;24:115–125. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-828889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel T. Increasing incidence and mortality of primary intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States. Hepatology. 2001;33:1353–1357. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.25087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.West J, Wood H, Logan RFA, Quinn M, Aithal GP. Trends in the incidence of primary liver and biliary tract cancers in England and Wales 1971–2001. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:1751–1758. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khan SA, Taylor-Robinson SD, Toledano MB, Beck A, Elliott P, Thomas HC. Changing international trends in mortality rates for liver, biliary and pancreatic tumours. J Hepatol. 2002;37:806–813. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00297-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carriaga MT, Henson DE. Liver, gallbladder, extrahepatic bile ducts, and pancreas. [Review.] Cancer. 1995;75:171–190. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950101)75:1+<171::aid-cncr2820751306>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeOliveira ML, Cunningham SC, Cameron JL, Kamangar F, Winter JM, Lillemoe KD, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma – thirty-one-year experience with 564 patients at a single institution. Ann Surg. 2007;245:755–762. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000251366.62632.d3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thanasai J, Limpaiboon T, Jearanaikoon P, Bhudhisawasdi V, Khuntikeo N, Sripa B, et al. Amplification of d-22s283 as a favourable prognostic indicator in liver fluke-related cholangiocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:4338–4344. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i27.4338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jan Y-Y, Yeh C-N, Yeh T-S, Chen T-C. Prognostic analysis of surgical treatment of peripheral cholangiocarcinoma: two decades of experience at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:1779–1784. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i12.1779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uenishi T, Hirohashi K, Kubo S, Yamamoto T, Yamazaki O, Kinoshita H. Clinicopathological factors predicting outcome after resection of mass-forming intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Surg. 2001;88:969–974. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inoue K, Makuuchi M, Takayama T, Torzilli G, Yamamoto J, Shimada K, et al. Longterm survival and prognostic factors in the surgical treatment of mass-forming type cholangiocarcinoma. Surgery. 2000;127:498–505. doi: 10.1067/msy.2000.104673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamamoto M, Takasaki K, Yoshikawa T. Extended resection for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in Japan. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1999;6:117–121. doi: 10.1007/s005340050093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Madariaga JR, Iwatsuki S, Todo S, Lee RG, Irish W, Starzl TE. Liver resection for hilar and peripheral cholangiocarcinomas: a study of 62 cases. Ann Surg. 1998;227:70–79. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199801000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng QB, Luo XJ, Zhang BH, Jiang XQ, Yi B, Wu MC. Distal bile duct carcinoma: prognostic factors after curative surgery. A series of 112 cases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:1212–1219. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9260-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murakami Y, Uemura K, Hayashidani Y, Sudo T, Hashimoto Y, Ohge H, et al. Prognostic significance of lymph node metastasis and surgical margin status for distal cholangiocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2007;95:207–212. doi: 10.1002/jso.20668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshida T, Matsumoto T, Sasaki A, Morii Y, Aramaki M, Kitano S. Prognostic factors after pancreatoduodenectomy with extended lymphadenectomy for distal bile duct cancer. Arch Surg. 2002;137:69–73. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.137.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fong Y, Blumgart LH, Lin E, Fortner JG, Brennan MF. Outcome of treatment for distal bile duct cancer. Br J Surg. 1996;83:1712–1715. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800831217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Todoroki T. Chemotherapy for bile duct carcinoma in the light of adjuvant chemotherapy to surgery. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:644–649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thongprasert S. The role of chemotherapy in cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2005;16(Suppl 2):93–96. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takada T, Amano H, Yasuda H, Nimura Y, Matsushiro T, Kato H, et al. Is postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy useful for gallbladder carcinoma? A phase III multicentre prospective randomized controlled trial in patients with resected pancreaticobiliary carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;95:1685–1695. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valle J, Wasan H, Palmer DH, Cunningham D, Anthoney A, Maraveyas A, et al. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1273–1281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Endo I, Gonen M, Yopp AC, Dalal KM, Zhou Q, Klimstra D, et al. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma – rising frequency, improved survival, and determinants of outcome after resection. Ann Surg. 2008;248:84–96. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318176c4d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bismuth H, Adam R, Levi F, Farabos C, Waechter F, Castaing D, et al. Resection of non-resectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Ann Surg. 1996;224:509–520. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199610000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kallioniemi A. CGH microarrays and cancer. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2008;19:36–40. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lohrisch C, Piccart M. An overview of HER2. [Review.] Semin Oncol. 2001;28:3–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kallioniemi A, Kallioniemi OP, Sudar D, Rutovitz D, Gray JW, Waldman F, et al. Comparative genomic hybridization for molecular cytogenetic analysis of solid tumours. Science. 1992;258:818–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1359641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Inazawa J, Inoue J, Imoto I. Comparative genomic hybridization (CGH)-arrays pave the way for identification of novel cancer-related genes. Cancer Sci. 2004;95:559–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb02486.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pinkel D, Albertson DG. Comparative genomic hybridization. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2005;6:331–354. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.6.080604.162140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fiegler H, Carr P, Douglas EJ, Burford DC, Hunt S, Smith J, et al. DNA microarrays for comparative genomic hybridization based on DOP-PCR amplification of BAC and PAC clones. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2003;36:361–374. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lipshutz RJ, Fodor SPA, Gingeras TR, Lockhart DJ. High density synthetic oligonucleotide arrays. Nat Genet. 1999;21:20–24. doi: 10.1038/4447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sobin LH, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours. 7th edn. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Beers EH, Joosse SA, Ligtenberg MJ, Fles R, Hogervorst FBL, Verhoef S, et al. A multiplex PCR predictor for ACGH success of FFPE samples. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:333–337. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.R Foundation for Statistical Computing. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. 2010. http://www.R-project.org [Accessed 01 February 2010]

- 33.Neuvial P, Hupe P, Brito I, Liva S, Manie E, Brennetot C, et al. Spatial normalization of array-CGH data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:264–284. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Venkatraman ES, Olshen AB. A faster circular binary segmentation algorithm for the analysis of array CGH data. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:657–663. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van de Wiel MA, Kim KI, Vosse SJ, van Wieringen WN, Wilting SM, Ylstra B. CCGcall: calling aberrations for array CGH tumour profiles. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:892–894. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van de Wiel MA, van Wieringen WN. CGH regions: dimension reduction for array CGH data with minimal information loss. Cancer Inform. 2007;3:55–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hofmann M, Stoss O, Shi D, Buttner R, van de Vijver M, Kim W, et al. Assessment of a HER2 scoring system for gastric cancer: results from a validation study. Histopathology. 2008;52:797–805. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2008.03028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ruschoff J, Dietel M, Baretton G, Arbogast S, Walch A, Monges G, et al. HER2 diagnostics in gastric cancer – guideline validation and development of standardized immunohistochemical testing. Virchows Arch. 2010;457:299–307. doi: 10.1007/s00428-010-0952-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Santarius T, Shipley J, Brewer D, Stratton MR, Cooper CS. Epigenetics and genetics: a census of amplified and overexpressed human cancer genes. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:59–64. doi: 10.1038/nrc2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yeh IT, Martin MA, Robetorye RS, Bolla AR, McCaskill C, Shah RK, et al. Clinical validation of an array CGH test for HER2 status in breast cancer reveals that polysomy 17 is a rare event. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:1169–1175. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2009.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Altimari A, Fiorentino M, Gabusi E, Gruppioni E, Corti B, D'Errico A, et al. Investigation of ErbB1 and ErbB2 expression for therapeutic targeting in primary liver tumours. Dig Liver Dis. 2003;35:332–338. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(03)00077-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ukita Y, Kato M, Terada T. Gene amplification and MRNA and protein overexpression of c-ErbB-2 (HER-2/neu) in human intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma as detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization, in situ hybridization, and immunohistochemistry. J Hepatol. 2002;36:780–785. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00057-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harder J, Waiz O, Otto F, Geissler M, Olschewski M, Weinhold B, et al. EGFR and HER2 expression in advanced biliary tract cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:4511–4517. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.4511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim HJ, Yoo TW, Park DI, Park JH, Cho YK, Sohn CI, et al. Gene amplification and protein overexpression of HER-2/neu in human extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma as detected by chromogenic in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry: its prognostic implication in node-positive patients. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:892–897. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nakazawa K, Dobashi Y, Suzuki S, Fujii H, Takeda Y, Ooi A. Amplification and overexpression of c-ErbB-2, epidermal growth factor receptor, and c-Met in biliary tract cancers. J Pathol. 2005;206:356–365. doi: 10.1002/path.1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shafizadeh N, Grenert JP, Sahai V, Kakar S. Epidermal growth factor receptor and HER-2/neu status by immunohistochemistry and fluorescence in situ hybridization in adenocarcinomas of the biliary tree and gallbladder. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:485–492. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chiba T, Zheng YW, Kita K, Yokosuka O, Saisho H, Onoidera M, et al. Enhanced self-renewal capability in hepatic stem/progenitor cells drives cancer initiation. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:937–950. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoshikawa D, Ojima H, Iwasaki M, Hiraoka N, Kosuge T, Kasai S, et al. Clinicopathological and prognostic significance of EGFR, VEGF, and HER2 expression in cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:418–425. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Voravud N, Foster CS, Gilbertson JA, Sikora K, Waxman J. Oncogene expression in cholangiocarcinoma and in normal hepatic development. Hum Pathol. 1989;20:1163–1168. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(89)80006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Choi HJ, Kim HJ, Choi JH. Expression of c-ErbB-2 and cyclooxygenase-2 in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2009;56:606–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Collier JD, Guo K, Mathew J, May FEB, Bennett MK, Corbett IP, et al. C-ErbB-2 oncogene expression in hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. 1992;14:377–380. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(92)90186-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brunt EM, Swanson PE. Immunoreactivity for c-ErbB-2 oncopeptide in benign and malignant diseases of the liver. Am J Clin Pathol. 1992;97 (Suppl):53–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chow NH, Huang SM, Chan SH, Mo LR, Hwang MH, Su WC. Significance of c-ErbB-2 expression in normal and neoplastic epithelium of biliary-tract. Anticancer Res. 1995;15:1055–1059. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ashida K, Terada T, Kitamura Y, Kaibara N. Expression of e-cadherin, alpha-catenin, beta-catenin, and CD44 (standard and variant isoforms) in human cholangiocarcinoma: an immunohistochemical study. Hepatology. 1998;27:974–982. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ito Y, Takeda T, Sasaki Y, Sakon M, Yamada T, Ishiguro S, et al. Expression and clinical significance of the ErbB family in intrahepatic cholangiocellular carcinoma. Pathol Res Pract. 2001;197:95–100. doi: 10.1078/0344-0338-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aishima SI, Taguchi KI, Sugimachi K, Shimada M, Tsuneyoshi M. C-ErbB-2 and c-Met expression relates to cholangiocarcinogenesis and progression of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Histopathology. 2002;40:269–278. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2002.00353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Endo K, Yoon BI, Pairojkul C, Demetris AJ, Sirica AE. ErbB-2 overexpression and cyclooxygenase-2 upregulation in human cholangiocarcinoma and risk conditions. Hepatology. 2002;36:439–450. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.34435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Settakorn J, Kaewpila N, Burns GF, Leong ASY. Fat, e-cadherin, beta catenin, HER2/neu, ki67 immunoexpression, and histological grade in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58:1249–1254. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2005.026575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Homayounfar K, Gunawan B, Cameron S, Halter F, Baumhoer D, Uecker S, et al. Pattern of chromosomal aberrations in primary liver cancers identified by comparative genomic hybridization. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:834–842. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rijken AM, Hu J, Perlman EJ, Morsberger LA, Long P, Kern SE, et al. Genomic alterations in distal bile duet carcinoma by comparative genomic hybridization and karyotype analysis. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1999;26:185–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Koo SH, Ihm CH, Kwon KC, Park JW, Kim JM, Kong G. Genetic alterations in hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2001;130:22–28. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(01)00460-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee JY, Park YN, Uhm KO, Park SY, Park SH. Genetic alterations in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma as revealed by degenerate oligonucleotide primed PCR-comparative genomic hybridization. J Korean Med Sci. 2004;19:682–687. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2004.19.5.682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Uhm KO, Park YN, Lee JY, Yoon DS, Park SH. Chromosomal imbalances in Korean intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma by comparative genomic hybridization. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2005;157:37–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shiraishi K, Okita K, Harada T, Kusano N, Furui T, Kondoh S, et al. Comparative genomic hybridization analysis of genetic aberrations associated with development and progression of biliary tract carcinomas. Cancer. 2001;91:570–577. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010201)91:3<570::aid-cncr1036>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shiraishi K, Kusano N, Okita S, Oga A, Okita K, Sasaki K. Genetic aberrations detected by comparative genomic hybridization in biliary tract cancers. Oncol-Basel. 1999;57:42–49. doi: 10.1159/000011999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shiraishi K, Okita K, Kusano N, Harada T, Kondoh S, Okita S, et al. A comparison of DNA copy number changes detected by comparative genomic hybridization in malignancies of the liver, biliary tract and pancreas. Oncol-Basel. 2001;60:151–161. doi: 10.1159/000055313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kim T, Cho S, Huh S, Kong Y, Sohn W, Hwang S, et al. A nationwide survey on the prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections in the Republic of Korea, 2004. Korean J Parasitol. 2009;47:37–47. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2009.47.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Harinasuta C, Harinasuta T. Opisthorchis viverrini– lifecycle, intermediate hosts, transmission to man and geographical distribution in Thailand. Arzneimittelforschung/Drug Res. 1984;34-2:1164–1167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vatanasapt V, Martin N, Sriplung H, Chindavijak K, Sontipong S, Sriamporn S, et al. Cancer incidence in Thailand, 1988–1991. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1995;4:475–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kubo S, Kinoshita H, Hirohashi K, Hamba H. Hepatolithiasis associated with cholangiocarcinoma. World J Surg. 1995;19:637–641. doi: 10.1007/BF00294744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jinawath N, Chamgramol Y, Furukawa Y, Obama K, Tsunoda T, Sripa B, et al. Comparison of gene expression profiles between Opisthorchis viverrini and non-Opisthorchis viverrini associated human intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology. 2006;44:1025–1038. doi: 10.1002/hep.21330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ahrens W, Timmer A, Vyberg M, Fletcher T, Guenel P, Merler E, et al. Risk factors for extrahepatic biliary tract carcinoma in men: medical conditions and lifestyle results from a European multicentre case–control study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19:623–630. doi: 10.1097/01.meg.0000243876.79325.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. JAMA. 2010;303:235–241. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rennie KL, Jebb SA. Prevalence of obesity in Great Britain. Obes Rev. 2005;6:11–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Geyer CE, Forster J, Lindquist D, Chan S, Romieu CG, Pienkowski T, et al. Lapatinib plus capecitabine for HER2-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2733–2743. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa064320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ramanathan RK, Belani CP, Singh DA, Tanaka M, Lenz HJ, Yen Y, et al. A phase II study of lapatinib in patients with advanced biliary tree and hepatocellular cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2009;64:777–783. doi: 10.1007/s00280-009-0927-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Philip PA, Mahoney MR, Allmer C, Thomas J, Pitot HC, Kim G, et al. Phase II study of erlotinib in patients with advanced biliary cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3069–3074. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.3579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhu AX, Meyerhardt JA, Blaszkowsky LS, Kambadakone A, Muzikansky A, Zheng H, et al. Efficacy and safety of gemcitabine, oxaliplatin, and bevacizumab in advanced biliary-tract cancers and correlation of changes in 18-fluorodeoxyglucose PET with clinical outcome: a phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:48–54. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70333-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lubner S, Mahoney M, Kolesar J, Loconte N, Kim G, Pitot H, et al. Report of a multicentre phase II trial testing a combination of biweekly bevacizumab and daily erlotinib in patients with unresectable biliary cancer: a phase II consortium study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3491–3497. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.4075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wedge SR, Kendrew J, Hennequin LF, Valentine PJ, Barry ST, Brave SR, et al. AZD2171: a highly potent, orally bioavailable, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor for the treatment of cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4389–4400. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Valle W, Bridgewater A, Roughton M, Dive S, Hughes S, Wasan H. ABC-03: a randomized, phase II/III study of cediranib (AZD2171) or placebo in combination with cisplatin/gemcitabine for patients with advanced biliary tract cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(Suppl):TPS218. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Von Hoff DD, Stephenson JJ, Jr, Rosen P, Loesch DM, Borad MJ, Anthony S, et al. Pilot study using molecular profiling of patients' tumours to find potential targets and select treatments for their refractory cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4877–4882. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.5983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]