Abstract

Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis following total proctocolectomy has become part of the standard surgical treatment for patients with ulcerative colitis or familial adenomatous polyposis who require colectomy. Although this surgery has improved patient quality of life and significantly reduced the risk of dysplasia or neoplasia in ulcerative colitis patients, complications are common. Pouchitis is the most common long-term complication of ileal pouch surgery and has a significant adverse impact on patient quality of life. The diagnosis and differential diagnosis of pouchitis are not straightforward, and the management of pouchitis, particularly chronic antibiotic-refractory pouchitis, which is one of the leading causes of pouch failures, can be challenging.

Keywords: Ileal pouch, inflammatory bowel disease, restorative proctocolectomy

The last decade has witnessed major advances in medical treatment of ulcerative colitis (UC). The options for medical therapy of moderate-to-severe UC have extended to anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α biologic regimens. However, it is not clear whether these new agents will ultimately alter the natural history of UC. Approximately 30% of patients with UC eventually require colectomy.1 Restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA) has become the surgical treatment of choice for the majority of patients with UC who fail medical therapy or develop dysplasia and the majority of patients with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP). The advantages of the surgical procedure include re-establishment of gastrointestinal continuity; improvement in health-related quality of life; positive impact on body image; avoidance of long-term use of UC-related medications in the majority of patients; and a substantial reduction in the risk of dysplasia or cancer. However, after the surgery, adverse outcomes or complications often occur, of which pouchitis is the most common long-term inflammatory complication.

Prevalence

Pouchitis is generally considered a nonspecific inflammatory condition in the ileal pouch reservoir.2 Reported cumulative frequency rates of pouchitis 10 years after IPAA surgery range from 23% to 46%.3,4 It is estimated that approximately 50% of patients who undergo IPAAA surgery for UC will develop at least 1 episode of pouchitis.5 The estimated incidence of pouchitis within 12 months of ileostomy take-down has been reported to be as high as 40% in one drug trial.6 The discrepancy in the reported cumulative frequencies from different institutions likely results from the variance in diagnostic criteria, the intensity of follow-up with or without pouch endoscopy, and the inclusion or exclusion of other inflammatory or functional disorders of the pouch and related surgical conditions.

Pathophysiology

Pouchitis almost exclusively occurs in patients with underlying UC or indeterminate colitis and is rarely seen in patients with FAP.7,8 Although the etiology and pathogenesis of pouchitis are not entirely clear, the alteration in bowel anatomy from the surgery may create an “inflammation-prone” environment. The normal function of the distal ileum, which involves the absorption of nutrients, is artificially converted to that of a storage reservoir. Qualitative and quantitative changes in the ileal pouch may constitute a triggering factor for the development of pouchitis.9–12 Evidence suggests that an abnormal mucosal immune response to altered microflora in the pouch leads to acute and/or chronic inflammation.6,12–15 Immune mechanisms of pouchitis have been extensively studied in a fashion similar to those of inflammatory bowel disease. An ex-vivo study has demonstrated that an ileal pouch of long duration has increased bacterial permeability.16–21 Proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α are released mainly in inflamed mucosa by macrophages and monocytes, leading to tissue injury, and are considered a secondary pathophysiologic mechanism in pouchitis.21 As in UC, the production of other inflammatory mediators, including cytokines,22–25 cell adhesion molecules,26 platelet-activating factor,27 lipoxygenase products of arachidonic acids,28 and proinflammatory neuropeptides23,29–31 is also increased. Abnormalities of immunoregulatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-2, interferon-gamma,19,32 IL-4,32 and IL-10 are also seen in pouchitis. Imbalance between proinflammatory and immunoregulatory cytokines has been described in patients with pouchitis.25 However, it is likely that those abnormalities in mucosal immunity are nonspecific and secondary in nature.

Risk Factors

The risk factors associated with pouchitis have been extensively studied. Genetic polymorphisms such as those associated with the IL-1 receptor antagonist33–35 and NOD2/CARD1536 may increase the risk of pouchitis. The reported risk factors of pouchitis also include noncarrier status of TNF allele 2,35 extensive UC,4,37,38 backwash ileitis,37 proctocolectomy thrombocytosis,39 concurrent primary sclerosing cholangitis,3,40,41 seropositive perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (pANCA),42,43 being a nonsmoker,38,44 and use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID).38,44 In addition to pANCA, the presence of the serologic markers anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (ASCA), the Crohn's disease (CD)-related antigen from Pseudomonas fluorescens, and the outer membrane porin C of Escherichia coli in patients with pre-operative indeterminate colitis appears to be associated with persistent inflammation of the pouch after restorative proctocolectomy.45 Acute and chronic pouchitis may be associated with different risk factors.38,46

Presentation

Patients with pouchitis can develop a wide range of clinical presentations, including increased stool frequency, urgency, tenesmus, incontinence, nocturnal seepage, abdominal cramping, and pelvic discomfort. Although bloody bowel movements are uncommon in typical pouchitis, patients with IPAA with or without pouchitis can have iron-deficiency anemia.47,48 Patients with severe pouchitis occasionally present with fever, dehydration, and malnutrition, which may require hospitalization. Patients may chiefly complain of predominantly extraintestinal symptoms such as arthralgia. These symptoms, however, can be present in other disorders of the pouch, including cuffitis, CD of the pouch, proximal small-bowel bacterial overgrowth, and irritable pouch syndrome.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of pouchitis should not depend solely upon the presenting symptoms of a patient. The severity of symptoms does not necessarily correlate with the degree of endoscopic or histologic inflammation of the pouch.49,50 A combined assessment of symptoms and endoscopic and histologic features is ideal for the diagnosis and differential diagnosis of pouchitis. There are no universally accepted diagnostic criteria for pouchitis. The 18-point Pouchitis Disease Activity Index (PDAI), although the most commonly used index in clinical trials, is seldom utilized in routine clinical practice.51

Pouch endoscopy yields valuable information on the severity and extent of mucosal inflammation (Figure 1), the presence or absence of concurrent backwash ileitis, CD of the pouch (Figure 2) or cuffitis (Figure 3), and the presence or absence of structural abnormalities such as strictures, sinus openings, and fistula openings. In addition, pouch endoscopy with segmental biopsy is the main surveillance procedure for dysplasia and can deliver effective therapy, including balloon stricture dilations and polypectomy. Histopathology is invaluable for the detection of dysplasia or neoplasia, viral inclusion bodies of cytomegalovirus infection, granulomas, pyloric gland metaplasia, mucosal prolapse, and ischemic changes. It should be noted that villous blunting and an increase in the number of mononuclear cells in the lamina propria can be part of the “normal” adaptive changes of the pouch mucosa to fecal stasis in the pouch and do not necessarily indicate pouchitis or CD of the pouch.

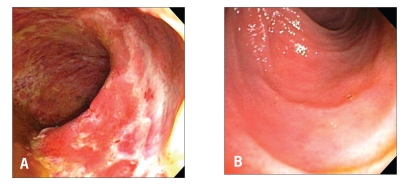

Figure 1.

Active pouchitis: Diffuse endoscopic inflammation of the pouch (A) with normal afferent limb mucosa (B).

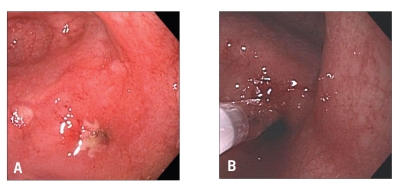

Figure 2.

Crohn's disease of the pouch: Pouch inlet stricture (A) with balloon dilation therapy (B).

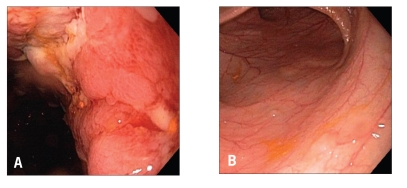

Figure 3.

Cuffitis: Inflammation at the anal transitional zone or cuff (A) with normal pouch mucosa (B).

In cases of suspected complicated pouchitis, CD of the pouch and complications related to surgical procedures should be excluded. Imaging studies such as contrast pouchography, computed tomography, and particularly magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvis are typically utilized to assess the presence of mucosal and transmural disease activity within and around the pouch.52 Wireless capsule endoscopy appears to be safe for use in patients with chronic pouchitis53 or anemia54 for assessment of small-bowel diseases.

Disease Variance

The disease course of pouchitis varies. Pouchitis likely represents a disease spectrum from acute, antibiotic-responsive to chronic, antibiotic-refractory. Based upon various criteria, pouchitis can be classified into the following categories: idiopathic versus secondary (based upon etiology); remission versus active (based upon disease status); acute versus chronic (based upon disease duration); infrequent episodes versus relapsing disease versus continuous disease (based upon disease pattern); and responsive versus refractory (based upon response to antibiotic therapy).55 Although the majority of patients with pouchitis respond favorably to antibiotic therapy, particularly in the initial stages of disease, some patients develop pouchitis refractory to routine antibiotic treatment. This leads to an additional useful clinical classification based upon the response to antibiotic therapy.56 Analogous to the classification of UC according to response to or dependency on corticosteroids, pouchitis can be classified based upon the manner of the patient's response to antibiotics: antibiotic-responsive, antibiotic-dependent, or antibiotic-refractory pouchitis.44 A subpopulation of patients experience pouchitis associated with identifiable and modifiable causes (namely secondary pouchitis), such as Clostridium difficile57,58 and cytomegalovirus59,60 infections as well as regular NSAID use.61 A recent study using immunohis-tochemistry and polymerase chain reaction found that viral genes and proteins were detected in samples from 12 of 34 patients (35.2%) with pouches, more frequently in patients with pouchitis than those without pouchitis. Cytomegalovirus infection may contribute to the disease course of pouchitis in some patients,62 though whether antiviral therapy is beneficial is not clear.

Disease Management

As the majority of patients who develop acute pouchitis do so within the first year post-IPAA,63 the probiotic VSL#3, which contains viable lyophilized bacteria with 4 strains of Lactobacillus, 3 strains of Bifidobacterium species, and Streptococcus salivarius subsp. Thermophilus, was evaluated for the primary prophylaxis of the initial pouchitis episode. Two of 20 patients (10%) treated with VSL#3 developed pouchitis within 12 months after IPAA, whereas 8 of 20 patients (40%) experienced pouchitis in the placebo group during the same period of time.6

Management and prognosis vary among the different types of pouchitis. For antibiotic-responsive pouchitis, first-line therapy includes a 14-day course of metronidazole (15–20 mg/kg/day) or ciprofloxacin (1,000 mg/day).64,65 A randomized trial of ciprofloxacin and metronidazole showed that patients treated with ciprofloxacin experienced significantly greater reductions in PDAI scores and fewer adverse effects than those treated with metronidazole.65 A small randomized trial of oral rifaximin 1,200 mg daily versus placebo (N=18) showed a marginal therapeutic benefit for active pouchitis.66 Other agents used in open-label trials include tetracycline, clarithromycin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, doxycycline, rifaximin, budesonide enemas,67 alicaforsen enemas, an antisense inhibitor of intercellular adhesion molecule-1,68 and AST-120, a highly adsorptive, porous, carbon microsphere.69

Patients with antibiotic-dependent pouchitis often require long-term maintenance therapy with either antibiotics or probiotics for maintenance of disease remission. A randomized trial of VSL#3 at a dose of 6 g daily was conducted for the maintenance and secondary prophylaxis of pouchitis relapse after remission was induced by oral ciprofloxacin (1,000 mg/d) and rifaximin (2,000 mg/d). During the 9-month trial in 40 patients with relapsing pouchitis, only 15% of the probiotic group relapsed as opposed to 100% of the placebo group.14 A separate randomized trial of VSL#3 in patients with antibiotic-dependent pouchitis showed that 17 of 20 patients (85%) in the VSL#3 group maintained clinical remission compared to 1 of 16 patients (6%) in the placebo group.15 However, in a recent postmarket, open-label trial of VSL#3 in 31 patients with antibiotic-dependent pouchitis, patients received 2 weeks of treatment with ciprofloxacin followed by VSL#3.70 After 8 months, 6 of the 31 patients (19%) were still taking VSL#3 and the remaining 25 patients (81%) had stopped mainly due to the lack of efficacy, low compliance, or the development of adverse effects.70 A small open-label trial of high-dose VSL#3 showed that treatment with the agent resulted in remission in 16 of 23 patients (69%) with active pouchitis.71 However, the role of probiotics in induction therapy warrants further study.

Antibiotic-refractory pouchitis is often difficult to treat and a common cause of pouch failure. Patients typically do not respond to full-dose, single-agent antibiotic therapy. It is important to investigate contributing causes (in secondary pouchitis) related to failure of antibiotic therapy. Secondary causes of refractory disease include the use of NSAIDs, concurrent C. difficile or cytomegalovirus infection, celiac disease and other autoimmune disorders, cuffitis, CD of the pouch, pouch ischemia, and inflammatory polyps of the pouch.72 There have been no randomized trials in the literature for this category of pouchitis. For patients without obvious causes of pouchitis, treatment options include a prolonged course of combined antibiotic therapy, 5-aminosalicylates, corticosteroids, immunosuppressive agents, or even biologic therapy. Regimens reported to be safe and effective in open-label trials include ciprofloxacin (1,000 mg/d) combined with one of the following: rifaximin (2,000 mg/d),73,74 metronidazole (1,000 mg/d),75 or tinidazole (1,000–1,500 mg/d)76 for 4 weeks. However, maintenance of remission in this group of patients after induction therapy with dual antibiotics remains a challenge.77 In addition, overuse of antibiotics may explain the possibility that the microflora responsible for pouchitis may shift from conventional to nonconventional forms, such as C. difficile,58 fungi,78 or even parasites (the authors' nonpublished data). Anti-inflammatory agents, immunomodulators, and biologic therapy have been used to treat pouchitis; these agents include bismuth carbomer enemas, short-chain fatty acid enemas, glutamine enemas, mesalamine enemas, oral budesonide,79 6-mercaptopurine, and infliximab.

Natural History and Prognosis

The natural history of pouchitis is poorly defined. In a study of 100 consecutive UC patients who underwent restorative proctocolectomy with IPAA, 32 patients developed pouchitis episodes and 5 patients had chronic refractory pouchitis, 2 of whom had pouch.55 Few studies have been conducted to identify the natural history of pouch and pouchitis. Patients with initial episodes of pouchitis almost uniformly respond to antibiotic therapy. However, pouchitis relapse is common. Of the patients with acute pouchitis, 39% have a single acute episode that responds to antibiotic therapy whereas the remaining 61% of patients develop at least 1 recurrence.80 Approximately 5–19% of patients with acute pouchitis develop refractory or rapidly relapsing forms of the disease.81–83 The disease course of antibiotic-responsive pouchitis may evolve into antibiotic-dependent pouchitis and then antibiotic-refractory pouchitis. The latter is one of the leading causes for pouch failure, resulting in pouch excision or permanent diversion. Although concurrent primary sclerosing cholangitis appears to be a risk factor for pouchitis,3,40,41 liver transplantation with posttransplant use of immunosuppressive agents does not appear to have an adverse impact on the disease course of pouchitis.84,85 In addition, chronic inflammation of the pouch and cuff may convey an increased risk for the development of dysplasia or cancer.86,87

Summary

Pouchitis is the most common long-term complication of restorative proctocolectomy. Its natural history, however, has not yet been defined. Patients with pouchitis can have a wide range of clinical presentations, disease courses, and prognoses. As medical therapy for pouchitis is largely antibiotic-based, management of antibiotic-dependent and antibiotic-refractory pouchitis remains a challenge.

References

- 1.Dhillon S, Loftus EV, Jr, Tremaine WJ, Jewell DA, Harmsen WS, et al. The natural history of surgery for ulcerative colitis in a population-based cohort from Olmsted County, Minnesota. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:A819. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shen B, Fazio VW, Remzi FH, Delaney CP, Bennett AE, et al. Comprehensive evaluation of inflammatory and noninflammatory sequelae of ileal pouch-anal anastomoses. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:93–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Penna C, Dozois R, Tremaine W, Sandborn W, LaRusso N, et al. Pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis occurs with increased frequency in patients with associated primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gut. 1996;38:234–239. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.2.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fazio VW, Ziv Y, Church JM, Oakley JR, Lavery IC, et al. Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis complications and function in 1005 patients. Ann Surg. 1995;222:120–127. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199508000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stocchi L, Pemberton JH. Pouch and pouchitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2001;30:223–241. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(05)70175-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gionchetti P, Rizzello F, Helwig U, Venturi A, Lammers KM, et al. Prophylaxis of pouchitis onset with probiotic therapy: a double-blind placebo controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1202–1209. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Penna C, Tiret E, Kartheuser A, Hannoun L, Nordlinger B, Parc R. Function of ileal J pouch-anal anastomosis in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Br J Surg. 1993;80:765–767. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800800638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tjandra JJ, Fazio VW, Church JM, Oakley JR, Milsom JW, Lavery IC. Similar functional results after restorative proctocolectomy in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis and mucosal ulcerative colitis. Am J Surg. 1993;165:322–325. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80834-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dufiy M, O'Mahony L, Coffey JC, Collins JK, Shanahan F, et al. Sulfate-reducing bacteria colonize pouches formed for ulcerative colitis but not for familial adenomatous polyposis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:384–388. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6187-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nasmyth DG, Godwin PG, Dixon MF, Williams NS, Johnston D. Ileal ecology after pouch-anal anastomosis or ileostomy. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:817–824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Komanduri S, Gillevet PM, Sikaroodi M, Mutlu E, Keshavarzian A. Dysbiosis in pouchitis: evidence of unique microfloral patterns in pouch inflammation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:352–360. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sandborn WJ. Pouchitis following ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: definition, pathogenesis, and treatment. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1856–1860. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90832-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gosselink MP, Schouten WR, van Lieshout LM, Hop WC, Laman JD, Ruseler-van Embden JG. Delay of the first onset of pouchitis by oral intake of the probiotic strain Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:876–884. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0525-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gionchetti P, Rizzello F, Venturi A, Brigidi P, Matteuzzi D, et al. Oral bacteriotherapy as maintenance treatment in patients with chronic pouchitis: a doubleblind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:305–309. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.9370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mimura T, Rizzello F, Helwig U, Poggioli G, Schreiber S, et al. Once daily high dose probiotic therapy (VSL#3) for maintaining remission in recurrent or refractory pouchitis. Gut. 2004;53:108–114. doi: 10.1136/gut.53.1.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kroesen AJ, Leistenschneider P, Lehmann K, Ransco C, Dullat S, et al. Increased bacterial permeation in long-lasting ileoanal pouches. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:736–744. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200608000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Silva HJ, Jones M, Prince C, Kettlewell M, Mortensen NJ, Jewell DP. Lymphocyte and macrophage subpopulations in pelvic ileal reservoirs. Gut. 1991;32:1160–1165. doi: 10.1136/gut.32.10.1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirata I, Berrebi G, Austin LL, Keren DF. Dobbins WO 3rd. Immunohistological characterization of intraepithelial and lamina propria lymphocytes in control ileum and colon and inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1986;31:593–603. doi: 10.1007/BF01318690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stallmach A, Schafer F, Hoffman S, Weber S, Müller-Molaian I, et al. Increased state of activation of CD4 positive T cells and elevated interferon gamma production in pouchitis. Gut. 1998;43:499–505. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.4.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomas PD, Forbes A, Nicholls RJ. Ciclitira P Altered expression of the lymphocyte activation markers CD30 and CD27 in patients with pouchitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:258–264. doi: 10.1080/003655201750074519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldberg PA, Herbst F, Beckett CG, Martelli B, Kontakou M, et al. Leukocyte typing, cytokine expression and epithelial turnover in the ileal pouch in patients with ulcerative colitis and familial adenomatous polyposis. Gut. 1996;38:549–553. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.4.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel RT, Bain I, Youngs D, Keighley MR. Cytokine production in pouchitis is similar to that in ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:831–837. doi: 10.1007/BF02049839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt C, Giese T, Ludwig B, Menges M, Schilling M, et al. Increased cytokine transcripts in pouchitis reflect the degree of inflammation but not the underlying entity. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2006;21:419–426. doi: 10.1007/s00384-005-0024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gionchetti P, Campieri M, Belluzzi A, Bertinelli E, Ferretti M, et al. Mucosal concentrations of interleukin-1α, interleukin-6, interleukin-8, and tumor necrosis factor-α in pelvic ileal pouches. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39:1525–1531. doi: 10.1007/BF02088059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bulois P, Tremaine WJ, Maunoury V, Gambiez L, Hafraoui S, et al. Pouchitis is associated with mucosal imbalance between interleukin-8 and interleukin-10. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2000;6:157–164. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200008000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patel RT, Pall AA, Adu D, Keighley MR. Circulating soluble adhesion molecules in inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1995;7:1037–1041. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199511000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chaussade S, Denizot Y, Valleur P, Nicoli J, Raibaud P, et al. Presence of PAF-acether in stool of patients with pouch ileoanal anastomosis and pouchitis. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:419–423. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90646-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gertner DJ, Rampton DS, Madden MV, Talbot IC, Nicholls RJ, Lennard-Jones JE. Increased leukotriene B4 release from ileal pouch mucosa in ulcerative colitis compared with familial adenomatous polyposis. Gut. 1994;35:1429–1432. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.10.1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stucchi AF, Shebani KO, Leeman SE, Wang CC, Reed KL, et al. A neurokinin 1 receptor antagonist reduces an ongoing ileal pouch inflammation and the response to a subsequent inflammatory stimulus. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;285:G1259–1267. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00063.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stallmach A, Chan CC, Ecker KW, Feifel G, Herbst H, et al. Comparable expression of matrix metalloproteinases 1 and 2 in pouchitis and ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2000;47:415–422. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.3.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ulisse S, Gionchetti P, D'Alo S, Russo FP, Pesce I, et al. Expression of cytokines, inducible nitric oxide synthase, and matrix metalloproteinases in pouchitis: effects of probiotic treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2691–2699. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas PD, Forbes A, Nicholls RJ, Ciclitira PJ. Increased mucosal IFN-γ production in pouchitis despite normal functional responses of isolated CD4 cells. Gut. 1999;44(suppl 4):32A. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carter MJ, Di Giovine FS, Cox A, Goodfellow P, Jones S, et al. The interleukin 1 receptor antagonist gene allele 2 as a predictor of pouchitis following colectomy and IPAA in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:805–811. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.28017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brett PM, Yasuda N, Yiannakou JY, Herbst F, Ellis HJ, et al. Genetic and immunological markers in pouchitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;8:951–955. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199610000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aisenberg J, Legnani PE, Nilubol N, Cobrin GM, Ellozy SH, et al. Are pANCA, ASCA, or cytokine gene polymorphisms associated with pouchitis? Long-term follow-up in 102 ulcerative colitis patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:432–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meier C, Hegazi RA, Aisenberg J, Legnani PE, Nilubol N, et al. Innate immune receptor genetic polymorphisms in pouchitis: is CARD15 a susceptibility factor? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11:965–971. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000186407.25694.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmidt CM, Lazenby AJ, Hendrickson RJ, Sitzmann JV. Preoperative terminal ileal and colonic resection histopathology predicts risk of pouchitis in patients after ileoanal pull-through procedure. Ann Surg. 1998;227:654–662. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199805000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Achkar JP, Al-Haddad M, Lashner B, Remzi FH, Brzezinski A, et al. Differentiating risk factors for acute and chronic pouchitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:60–66. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00604-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okon A, Dubinsky M, Vasiliauskas EA, Papadakis KA, Ippoliti A, et al. Elevated platelet count before ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis is associated with the development of chronic pouchitis. Am Surg. 2005;71:821–826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shepherd NA, Hulten L, Tytgat GN, Nicholls RJ, Nasmyth DG, et al. Pouchitis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1989;4:205–229. doi: 10.1007/BF01644986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hata K, Watanabe T, Shinozaki M, Nagawa H. Patients with extraintestinal manifestations have a higher risk of developing pouchitis in ulcerative colitis: multivariate analysis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:1055–1058. doi: 10.1080/00365520310005938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fleshner PR, Vasiliauskas EA, Kam LY, Fleshner NE, Gaiennie J, et al. High level perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (pANCA) in ulcerative colitis patients before colectomy predicts the development of chronic pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Gut. 2001;49:671–677. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.5.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuisma J, Jarvinen H, Kahri A, Farkkilla M. Factors associated with disease activity of pouchitis after surgery for ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:544–548. doi: 10.1080/00365520410004668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shen B, Fazio VW, Remzi FH, Brzezinski A, Bennett AE, et al. Risk factors for diseases of ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in patients with ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hui T, Landers C, Vasiliauskas E, Abreu M, Dubinsky M, et al. Serologic responses in indeterminate colitis patients before ileal pouch-anal anastomosis may determine those at risk for continuous pouch inflammation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1254–1262. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abdelrazeq AS, Kandiyil N, Botterill ID, Lund JN, Reynolds JR, et al. Predictors for acute and chronic pouchitis following restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis. Colorectal Dis. 2007 Nov 12; doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2007.01413.x. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pastrana RJ, Torres EA, Arroyo JM, Rivera CE, Sanchez CJ, Morales L. Irondeficiency anemia as presentation of pouchitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:41–44. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000212641.90477.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oikonomou IK, Fazio VW, Remzi FH, Lopez R, Lashner BA, Shen B. Risk factors for anemia in patients with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;48:1254–1262. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0752-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shen B, Achkar JP, Lashner BA, Ormsby AH, Remzi FH, et al. Endoscopic and histologic evaluation together with symptom assessment are required to diagnose pouchitis. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:261–267. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.26290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moskowitz RL, Shepherd NA, Nicholls RJ. An assessment of inflammation in the reservoir after restorative proctocolectomy with ileoanal ileal reservoir. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1986;1:167–174. doi: 10.1007/BF01648445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ, Batts KP, Pemberton JH, Phillips SF. Pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: a Pouchitis Disease Activity Index. Mayo Clin Proc. 1994;69:409–415. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)61634-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nadgir RN, Soto JA, Dendrinos K, Lucey BC, Becker JM, Farraye FA. MRI of complicated pouchitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:W386–391. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Calabrese C, Fabbri A, Gionchetti P, Rizzello F, Morselli C, et al. Controlled study using wireless capsule endoscopy for the evaluation of the small intestine in chronic refractory pouchitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:1311–1316. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shen B, Remzi FH, Santisi J, Lashner BA, Brzezinski A, Fazio VW. Application of wireless capsule endoscopy for the evaluation of iron deficiency anemia in patients with ileal pouches. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008 Mar 19; doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318074dd73. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sandborn WJ. Pouchitis: Risk factors, frequency, natural history, classification and public health prospective. In: McLeod RS, Martin F, Sutherland LR, Wallace JL, Williams CN, editors. Trends in Inflammatory Bowel Disease 1996. Lancaster, UK: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1997. pp. 51–63. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shen B. Diagnosis and management of patients with pouchitis. Drugs. 2003;65:453–461. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200363050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mann SD, Pitt J, Springall RG, Thillainayagam AV. Clostridium difficile infection—an unusual cause of refractory pouchitis: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:267–270. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6533-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shen B, Goldblum JR, Hull TL, Remzi FH, Bennett AE, Fazio VW. Clostridium difficile-associated pouchitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:2361–2364. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9172-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Munoz-Juarez M, Pemberton JH, Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ, Dozois RR. Misdiagnosis of specific cytomegalovirus infection of the ileoanal pouch as refractory idiopathic chronic pouchitis: report of two cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:117–120. doi: 10.1007/BF02235196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moonka D, Furth EE, MacDermott RP, Lichtenstein GR. Pouchitis associated with primary cytomegalovirus infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:264–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shen B, Fazio VW, Remzi FH, Bennett AE, Lopez R, et al. Effect of withdrawal of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use on ileal pouch disorders. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:3321–3328. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9710-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Casadesus D, Tani T, Wakai T, Maruyama S, Iiai T, et al. Possible role of human cytomegalovirus in pouchitis after proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in patients with ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:1085–1089. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i7.1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stahlberg D, Gullberg K, Liljeqvist L, Hellers G, Lofberg R. Pouchitis following pelvic pouch operation for ulcerative colitis. Incidence, cumulative risk, and risk factors. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:1012–1018. doi: 10.1007/BF02054692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Madden MV, McIntyre AS, Nicholls RJ. Double-blind crossover trial of metronidazole versus placebo in chronic unremitting pouchitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39:1193–1196. doi: 10.1007/BF02093783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shen B, Achkar JP, Lashner BA, Ormsby AH, Remzi FH, et al. A randomized trial of ciprofloxacin and metronidazole in treating acute pouchitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2001;7:301–305. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200111000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Isaacs KL, Sandler RS, Abreu M, Picco MF, Hanauer SB, et al. Crohn's and Colitis Foundation of America Clinical Alliance. Rifaximin for the treatment of active pouchitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:1250–1255. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sambuelli A, Boerr L, Negreira S, Gil A, Camartino G, et al. Budesonide enema in pouchitis—a double-blind, double-dummy, controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:27–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Miner P, Wedel M, Bane B, Bradley J. An enema formulation of alicaforsen, an antisense inhibitor of intercellular adhesion molecule-1, in the treatment of chronic, unremitting pouchitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:281–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shen B, Pardi DS, Bennett AE, Sherman KK. A pilot study of the efficacy and tolerability of AST-120 in the treatment of active pouchitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:A979. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shen B, Brzezinski A, Fazio VW, Remzi FH, Achkar JP, et al. Maintenance therapy with a probiotic in antibiotic-dependent pouchitis: experience in clinical practice. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:721–728. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gionchetti P, Rizzello F, Morselli C, Poggioli G, Tambasco R, et al. Highdose probiotics for the treatment of active pouchitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:2075–2082. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9068-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schaus BJ, Fazio VW, Remzi FH, Bennett AE, Lashner BA, Shen B. Large polyps in the ileal pouch in patients with underlying ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;50:832–838. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0871-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gionchetti P, Rizzello F, Venturi A, Ugolini F, Rossi M, et al. Antibiotic combination therapy in patients with chronic treatment-resistant pouchitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:713–718. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Abdelrazeq AS, Kelly SM, Lund JN, Leveson SH. Rifaximin-ciprofloxacin combination therapy is effective in chronic active refractory pouchitis. Colorectal Dis. 2005;7:182–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2004.00746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mimura T, Rizzello F, Helwig U, Poggioli G, Schreiber S, et al. Four-week open-label trial of metronidazole and ciprofloxacin for the treatment of recurrent or refractory pouchitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:909–917. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shen B, Fazio VW, Remzi FH, Bennett AE, Lopez R, et al. Combined ciprofloxacin and tinidazole in the treatment of chronic refractory pouchitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:498–508. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0828-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Viscido A, Kohn A, Papi C, Caprilli R. Management of refractory fistulizing pouchitis with infliximab. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2004;8:239–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kühbacher T, Ott SJ, Helwig U, Mimura T, Rizzello F, et al. Bacterial and fungal microbiota in relation to probiotic therapy (VSL#3) in pouchitis. Gut. 2006;55:833–841. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.078303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gionchetti P, Rizzello F, Poggioli G, Pierangeli F, Laureti S, et al. Oral budesonide in the treatment of chronic refractory pouchitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:1231–1236. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lohmuller JL, Pemberton JH, Dozois RR, Ilstrup D, van Heerden J. Pouchitis and extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease after ileal pouchanal anastomosis. Ann Surg. 1990;211:622–629. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mowschenson PM, Critchlow JF, Peppercorn MA. Ileoanal pouch operation: long-term outcome with or without diverting ileostomy. Arch Surg. 2000;135:463–465. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.4.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hurst RD, Chung TP, Rubin M, Michelassi F. The implications of acute pouchitis on the long-term functional results after restorative proctocolectomy. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 1998;4:280–284. doi: 10.1002/ibd.3780040405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Madiba TE, Bartolo DC. Pouchitis following restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis: incidence and therapeutic outcome. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 2001;46:334–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zins BJ, Sandborn WJ, Penna CR, Landers CJ, Targan SR, et al. Pouchitis disease course after orthotopic liver transplantation in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis and an ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:2177–2180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Freeman K, Shao Z, Remzi FH, Lopez R, Fazio VW, Shen B. Impact of orthotopic liver transplant for primary sclerosing cholangitis on chronic antibiotic refractory pouchitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Das P, Johnson MW, Tekkis PP, Nicholls RJ. Risk of dysplasia and adenocarcinoma following restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9:15–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2006.01148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Thompson-Fawcett MW, Marcus V, Redston M, Cohen Z, McLeod RS. Risk of dysplasia in long-term ileal pouches and pouches with chronic pouchitis. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:275–281. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.26442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]