Abstract

BACKGROUND:

TREATMEN The contribution of eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) to refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) remains unknown. When EoE and GERD overlap, the clinical, endoscopic and histological findings are nonspecific and cannot be used to distinguish between the two disorders. Limited data are available on this topic, and the interaction between EoE and GERD is a matter of debate.

AIM:

We have conducted a prospective study of adult patients with refractory GERD to evaluate the overlap of reflux and EoE.

METHODS:

Between July 2006 and June 2008, we consecutively and prospectively enrolled 130 male and female patients aged 18 to 70 years old who experienced persistent heartburn and/or regurgitation more than twice a week over the last 30 days while undergoing at least six consecutive weeks of omeprazole treatment (at least 40 mg once a day). The patients underwent an upper digestive endoscopy with esophageal biopsy, and intraepithelial eosinophils were counted after hematoxylin/eosin staining. The diagnosis of EoE was based on the presence of 20 or more eosinophils per high-power field (eo/HPF) in esophageal biopsies.

RESULTS:

Among the 103 studied patients, 79 (76.7%) were females. The patients had a mean age of 45.5 years and a median age of 47 years. Endoscopy was normal in 83.5% of patients, and erosive esophagitis was found in 12.6%. Only one patient presented lesions suggestive of EoE. Histological examination revealed >20 eo/HPF in this patient.

CONCLUSION:

Our results demonstrated a low prevalence of EoE among patients with refractory GERD undergoing omeprazole treatment.

Keywords: Refractory Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease, Eosinophilic Esophagitis, Heartburn, Acid Regurgitation

INTRODUCTION

The persistence of typical gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms has become frequent in medical practice. GERD presents a major challenge with respect to patient follow-up because of the high cost of investigation,1 its association with functional involvement and the presence of symptoms associated with dyspeptic conditions.2 The literature has reported cases presenting with typical GERD symptoms (even without previous endoscopic or pH-metric investigation) that last at least two days a week for 30 days or more than once a week for three months and that are refractory to clinical treatment at any intensity or frequency, despite receiving a daily proton pump inhibitor dose of at least 40 mg.3

The refractory nature of the disorder can result from several factors, including treatment nonadherence,4 the presence of acid reflux or bile/duodenogastric reflux, visceral hypersensitivity, functional disease, psychological comorbidities and delayed gastric emptying.1

Over the last ten years, eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) has been increasingly studied. It has recently been associated with GERD.3,5,6

The most frequent EoE manifestations in adults are dysphagia,7 food impaction and chest pain. Heartburn is also present in up to 20% of cases, and it requires a differential diagnosis from GERD.8-10

Early studies observed that 1 to 15% of patients diagnosed with primary GERD presented with EoE.11,12 Among patients who underwent endoscopy, 6.5% had EoE;13 this value increased to 8.8% among patients with GERD.14 It is now suggested that the EoE is more prevalent among GERD patients who do not respond to treatment with PPI.7,15

The EoE prevalence in adults is not completely described in the literature when typical symptoms, such as heartburn and regurgitation, are mentioned. Accordingly, we proposed to determine the EoE prevalence in patients with persistent heartburn and/or regurgitation undergoing treatment with omeprazole.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

A total of 130 male and female patients aged 18 to 70 years old with a clinical diagnosis of refractory GERD were consecutively and prospectively enrolled between July 2006 and June 2008.

The inclusion criterion was the persistence of heartburn and/or regurgitation more than twice a week over the last 30 days while undergoing omeprazole treatment (at least 40 mg once a day) for at least six consecutive weeks.1,3

Patients with a previous history of upper digestive tract surgery, decompensated chronic diseases and/or consumptive diseases; pregnant or nursing women; and patients with a previous upper digestive endoscopy showing active peptic ulcer, esophageal diverticulum, Barrett's esophagus or esophageal obstruction were excluded from the study.

The study was submitted for the approval of the Ethics Committee on Research, and all patients signed an informed consent form.

All patients attended three appointments to classify their symptoms and to receive information about PPI administration and the clinical trial, including signs of a potential allergic reaction to the treatment. Patients who developed only atypical symptoms of persistence and those who were taking corticosteroids were excluded.

All patients underwent an upper digestive endoscopy (UDE) with esophageal biopsy and laboratory assessment. The Los Angeles endoscopic classification for GERD16 was used for the upper digestive endoscopy assessment. Hiatal hernia was defined as a protrusion larger than two centimeters above the esophageal-gastric transition.

All patients underwent esophageal biopsy five and 10 cm from the esophageal-gastric transition. Two samples were collected from each site, and one extra sample was taken when mucosal alterations (corrugations, erosions, signs of acanthosis or fungus or granular lesions) were observed; thus, five biopsy samples were taken to increase the diagnostic sensitivity. Instead of small intestine biopsy, we performed two stomach biopsies to rule out eosinophilic gastroenteritis, due to the high incidence of enteroparasitosis in Brazil.

All anatomopathological assessments were completed, and intraepithelial eosinophils (eo) were counted in up to six high-power fields (hpf: 0.158 mm2) (x400) after hematoxylin/eosin staining. All histological features were analyzed by a single pathologist blinded to the diagnosis and were reviewed by the researcher.

A diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis was established when the number of intraepithelial eosinophils in the esophagus was ≥20 eo/HPF and was associated with the absence of eosinophils in the gastric mucosa, which increased the diagnostic specificity, as suggested in the 2007 consensus.7

Blood samples were collected to determine the serum eosinophil level (complete blood count) and total IgE level. Three consecutive stool assessments were conducted to rule out parasitic infestation.

RESULTS

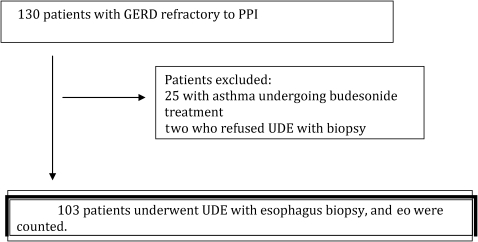

Overall, 130 patients were evaluated in the study. Of these, 25 were excluded because they used budesonide inhalers, and two were excluded because they refused to undergo upper digestive endoscopy (UDE) with biopsy (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Patient selection flowchart GERD: gastroesophageal reflux disease; PPI: proton pump inhibitor; UDE; upper digestive endoscopy; eo: eosinophils.

Among the 103 studied patients, 79 (76.7%) were female. Patients had a mean age of 45.5 years and a median age of 47 years.

The mean PPI dose was 76±9.1 (median of 80) mg per day (40 mg twice a day) for a mean time of 36.8±28.5 (median of 24) weeks. The characteristics of study population are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Study population characteristics PPI: proton pump inhibitor.

| Frequency | % | |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 79 | 76.7 |

| Male | 24 | 23.3 |

| Age, years | ||

| 18-30 | 8 | 7.8 |

| 31-40 | 23 | 22.3 |

| 41-50 | 36 | 35 |

| 51-60 | 30 | 29.1 |

| More than 60 | 6 | 5.8 |

| Escolarity | ||

| <8 years | 64 | 62.1 |

| >8 years | 39 | 37.9 |

| PPI dose | ||

| 40 mg | 1 | 0.97 |

| 60 mg | 27 | 26.2 |

| More than 80 mg | 75 | 72.8 |

| Tabagism | ||

| Yes | 12 | 11.7 |

| No | 91 | 88.3 |

| Symptoms | ||

| Dysphagia | 59 | 57.3 |

| Hoarseness | 61 | 59.2 |

| Postprandial fullness | 68 | 66 |

| Epigastralgia | 70 | 68 |

| Nausea | 56 | 34.9 |

| Globus hystericus | 42 | 40.8 |

| Coughing | 36 | 34.9 |

| Chest pain | 34 | 33 |

| Allergy | ||

| Yes | 67 | 65 |

| No | 36 | 35 |

| Comorbidity | ||

| Hypertension | 36 | 35 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3 | 2.9 |

| Depression | 31 | 30.1 |

| Fibromyalgia | 6 | 5.8 |

| Asthma | 7 | 6.8 |

| Thyroid disease | 8 | 7.8 |

Laboratory assessment results, including eosinophil count, serum IgE level and the presence of enteroparasitosis, are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Eosinophil (eo) count and serum IgE levels in patients with and without parasitosis.

| Frequency | % | IgE medium | eo plasmatic | |

| Patients with enteroparasitosis | 37 | 36 | ------------------ | ----------------- |

| Schistosoma mansoni | 3 | 2.01 | 3416 | 367 |

| Strongyloides stercoralis | 3 | 2.91 | 261 | 800 |

| Ancylostoma duodenale | 1 | 0.97 | 5 | 500 |

| Giardia lamblia | 1 | 0.97 | 72 | 100 |

| Entamoeba histolytica | 2 | 1.9 | 90 | 200 |

| Entamoeba coli | 13 | 12.6 | 179 | 133 |

| Hymenolepsis nana | 19 | 18.4 | 62 | 188 |

| Blastocystis hominis | 9 | 8.7 | 64 | 100 |

| Others | 2 | 1.9 | 23 | 250 |

| Average | ---------- | ---- | 463 | 293 |

| Patients without enteroparasitosis | 66 | 64 | 366 | 302 |

No esophageal lesion was observed on upper digestive endoscopy in 86 patients (83.5%), and 13 other patients (12.6%) presented persistent of erosive esophagitis (Los Angeles grade A) while undergoing treatment with PPI. Four patients presented other esophageal lesions, and only one presented lesions suggestive of EoE (i.e., a granular aspect and esophageal mucosa corrugations).

The esophageal biopsy outcomes, which included intraepithelial eosinophils counts in a high-power field, identified only one patient with EoE whose counts the distal and proximal thirds of the esophagus were >20 eo/HPF. Enteroparasitosis and gastroenteritis diagnoses were ruled out for this patient.

The other 102 patients presented a low eosinophil count, with a maximum of three eo/HPF, and no eosinophilic microabscesses were observed.Therefore, the EoE occurrence among patients previously diagnosed with GERD with persistent heartburn and/or regurgitation while undergoing PPI treatment was one in 103 studied patients (0.97%).

The patient presenting with EoE was a 23-year–old man. He used 80 mg of omeprazole, and he had a diagnosis of allergies with rhinitis. His plasmatic eosinophil count was 100, and his total IgE was 79. We excluded the possibility of viral and fungal infections. The endoscopy revealed a granular aspect and esophageal mucosa corrugations; the biopsy showed 32 and 23 eo/HPF in the distal and proximal regions of the esophagus, respectively. The patient underwent skin prick and patch tests, and the results indicated that he was sensitive to eggplant. Eggplant was excluded from his diet, and he was treated with 20 mg of montelukast. After three months of treatment, a new biopsy was conducted, and only one eosinophil was found.

DISCUSSION

During GERD treatment, PPIs are the most common and effective class of drugs prescribed to heal erosive esophagitis ; however, clinical trials have shown that ¼ of patients with erosive GERD have persistent heartburn symptoms after 30 days of treatment.17 Double doses and prolonged treatment have been described as factors that increase treatment efficacy,18 thus contributing to the fact that two of the five most commonly sold medications in the USA are PPIs. PPI sales per year have doubled since 1999.19

Nevertheless, PPI therapeutic failure has become one of the greatest clinical challenges in the management of patients with GERD.1

The definition of refractoriness to PPI is controversial and may be related to the persistence of symptoms (thus including patients with functional heartburn), the persistence of acid reflux upon pH-metry (thus including only patients with acid reflux) or even the presence of nonacid reflux upon impedance/pH-metry (which would also include patients with functional heartburn not defined by the impedance/pH-metry assessment).

A complementary assessment is only indicated when symptoms do not respond properly to a minimum PPI dose,20 as lower refractoriness rates are observed when patients take 40 mg/day of omeprazole. Accordingly, we chose to include in the present study patients who took 40 mg/day of omeprazole but experienced persistent typical symptoms (heartburn and/or regurgitation) at any intensity or frequency for at least two days a week over the last 30 days or more than once a week over the last three months.1,3

The main causes for therapeutic failure (i.e., incorrect drug administration and poor treatment adherence) were ruled out by supplying the medication, free of charge, throughout the entire pre-inclusion period of the study and by providing information on the correct time to take the medication. The patients were followed for at least six weeks by the researcher to monitor treatment adherence.

Eosinophilic esophagitis has been recently reported as a cause of GERD refractoriness. The present study defined GERD refractoriness specifically in terms of typical symptoms, excluding patients who only developed dysphagia or food impaction (the prevalent symptoms of EoE) with endoscopic findings and eosinophil counts that were not specific to EoE.21 Previous reports suggest that EoE would be high among patients with refractory GERD.14 We decided to perform four esophageal biopsies at two different levels, which could raise doubts about diagnostic sensitivity; however, we emphasize that other biopsies conducted when any mucosal alteration was observed, thus increasing the sensitivity to almost 100%. Because the outcomes obtained in patients with GERD undergoing treatment with omeprazole were negligible (up to three eo/HPF), we believe a sufficient number of biopsies were performed to produce a differential diagnosis.7 Furthermore, none of the patients presented an eosinophil count between 15 and 20 eo/HPF, indicating that the 20 eo/HPF cut-off for diagnosis was correct.

It is important to emphasize that this is the first prospective study to exclude the main cause of refractoriness (poor treatment adherence) and to demonstrate a low prevalence of EoE in patients with typical GERD symptoms (such as heartburn and/or regurgitation) who did not respond to an omeprazole dose of at least 40 mg.

Recently published articles corroborate the findings of the present study.22 Although our sample was predominantly female, the outcome is comparable to that of other studies that found the same results in male patients with EoE.23

Recent evidence has shown that the eosinophil count should not be the only criteria used to diagnose EoE.20 Although the results are not in agreement with those reported by other authors,14 this discrepancy does not call into question the validity of our results; the subjects of previous studies may have presented with GERD with a high eosinophil count, particularly in cases of treatment-naïve patients or patients undergoing low-dose treatment.

Additionally, the use of five serial biopsies in patients with persistent GERD symptoms undergoing omeprazole treatment would increase the costs of the investigation, with little benefit to most patients.

The high verminosis incidence among our patients is interesting, although we did not find eosinophils infiltrating into the digestive tract. Another important fact is that the IgE and eosinophil levels did not differ among the patients who did and did not present with verminosis, except among those who had S. mansoni and S. stercoralis and consequently developed higher levels of IgE and eosinophils, respectively. The question is whether the population with verminosiswould be less susceptible to allergic diseases and, as consequence, have a lower prevalence of EoE. Is there a real difference in the prevalence of EoE among populations with a high verminosis incidence? More research is necessary to study the correlation between the frequency of EoE and verminosis.

The search for additional data concerning the indications for esophageal biopsy is very important. The literature data and current studies demonstrate that this information could include a history of personal or familial atopy, asthma, male sex, young age, concerns about dysphagia or food impaction in the esophagus and screening for endoscopic alterations, even subtle ones.

CONCLUSION

The prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis is low in patients with persistent heartburn and/or regurgitation symptoms refractory to omeprazole treatment.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fass R, Shapiro R, Dekel R, Sewell J. Systematic review: proton-pump inhibitor failure in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease-where next. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:79–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02531.x. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02531.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tack J, Talley NJ, Camilleri M, Holtmann G, Hu P, Malagelada JR, et al. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1466–79. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.059. 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sgouros SN. Refractory heartburn to proton pump inhibitors: epidemiology, etiology and management. Digestion. 2006;73:218–27. doi: 10.1159/000094789. 10.1159/000094789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dal-Paz K, Navarro-Rodriguez T, Eisig JN, Barbuti RC, Chinzon D, Moraes-Filho JPP. Patients with GERD Treated with Proton-Pump Inhibitors Have Low Adherence to Outpatients-Based Treatment. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(suppl 1):A–441. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richter JE. How to manage refractory GERD. Nature Clinical Practice Gastroenterol & Hepatol. 2007;12:658–64. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep0979. 10.1038/ncpgasthep0979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fass R, Gasiorowska A. Refractory GERD: Whats is it? Current Gastroenterology Reports. 2008;10:252–7. doi: 10.1007/s11894-008-0052-5. 10.1007/s11894-008-0052-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Collins MH, Gupta SK, Justinich C, Putnam PE, et al. AGA Institute - Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Children and Adults: A Systematic Review and Consensus Recommendations for Diagnosis and Treatment. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1342–63. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.017. 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parfitt JR, Gregor JC, Suskin NG, Jawa HA, Driman DK. Eosinophilic esophagitis in adults: distinguishing features from Gastroesophageal reflux disease: a study of 41 patients. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:90–6. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800498. 10.1038/modpathol.3800498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pasha SF, DiBaise JK, Kim HJ, De Petris G, Crowell MD, Fleischer DE, et al. Patient characteristics, clinical, endoscopic, and histologic findings in adult eosinophilic esophagitis: a case series and systematic review of the medical literature. Diseases of the Esophagus. 2007;20:311–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2007.00721.x. 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2007.00721.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moraes-Filho JP, Navarro-Rodriguez T, Eisig JN, Barbuti RC, Chinzon D, Quigley EM. Comorbidities are frequent in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease in a tertiary health care hospital. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2009;64:785–90. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322009000800013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ronkainen J, Talley NJ, Aro P, Storskrubb T, Joahansson SE, Lindt T, et al. Prevalence of oesophageal eosinophils and eosinophilic oesophagitis in adults: the population-based Kalixanda study. Gut. 2007;56:615–20. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.107714. 10.1136/gut.2006.107714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupte AR, Draganov PV. Eosinophilic esophagitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:17–24. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.17. 10.3748/wjg.15.17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Veerappan GR, Perry J, Duncan TJ, Baker TP, Maydonovitch C, Lake JM, et al. Prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in an adult population undergoing upper endoscopy: a prospective study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:420–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.10.009. 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foroutan M, Norouzi A, Molaei M, Mirbagheri SA, Irvani S, Sadeghi A, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in patients with refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:28–31. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0706-z. 10.1007/s10620-008-0706-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Molina-Infante J, Ferrando-Lamana L, Mateos-Rodriguez JM, Pérez-Gallardo B, Prieto-Bermeio AB. Overlap of reflux and eosinophilic esophagitis in two patients requiring different therapies: a review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:1463–66. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.1463. 10.3748/wjg.14.1463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lundell LR, Dent J, Bennett JR, Blum AL, Armstrong D, Galmiche JP, et al. Endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis: clinical and functional correlates and further validation of the Los Angeles classification. Gut. 1999;45:172–80. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2.172. 10.1136/gut.45.2.172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chiba N, De Gara CJ, Wilkinson JM, Hunt RH. Speed of healing and symptom relief in grade II to IV gastroesophageal reflux disease: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1798–810. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9178669. 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9178669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malfertheiner P, Fass R, Quigley EM, Modlin IM, Malagelada JR, Moss SF, et al. Review article: from gastrin to gastro-oesophageal reflux disease – a century of acid suppression. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:683–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02817.x. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02817.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shaheen NJ, Hansen RA, Morgan DR, Gangarosa LM, Ringel Y, Thiny MT, et al. The burden of gastrointestinal and liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2128–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00723.x. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00723.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mainie I, Tutuian R, Shay S, Vela M, Zhang X, Sifrim D, et al. Acid and non-acid reflux in patients with persistent symptoms despite acide suppressive therapy: a multicentre study using combined ambulatory impedance-pHmonitoring. Gut. 2006;55:1398–402. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.087668. 10.1136/gut.2005.087668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodrigo S, Abboud G, Oh D, DeMeester SR, Hagen J, Lipham J, et al. High intraepithelial eosinophil counts in esophageal squamous epithelium are not specific for eosinophilic esophagitis in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:435–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01594.x. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01594.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poh CH, Gasiorowska A, Navarro-Rodriguez T, Willis MR, Hargadon D, Noelck N, et al. Upper GI tract findings in patients with heartburn in whom proton pump inhibitor treatment failed versus those not receiving antireflux treatment. Gastrointestinal Endosc. 2010;71:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.08.024. 10.1016/j.gie.2009.08.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poh CH, Gasiorowska A, Navarro-Rodriguez T, Willis MR, Noelck N, Fass R. Eosinophilic Esophagitis Is Uncommon in Male-Enriched Patient Population with Refractory Heartburn. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(suppl 1):A–283. [Google Scholar]