INTRODUCTION

Auditory training (AT) is a set of strategies applied to develop or improve auditory abilities.1 Two mechanisms are involved in auditory processing: neurocognitive mechanisms of the acoustic signal itself, which are responsible for the discrimination and recognition of a specific function (“bottom-up” processes), and attentional processes involving phenomena such as attention and memory (“top-down” processes).

Several studies have shown that auditory functions can be improved by stimulating those neurocognitive and attentional abilities.2,3 Nevertheless, it is not yet known whether AT can improve cognitive functioning. Although AT shares processes in common with cognition (such as attentional processes), it considers the processes as solely unimodal because only auditory stimuli are analyzed. This leads to the question of whether auditory training affects cognitive abilities.

This paper describes the audiological and cognitive findings of an adult with traumatic brain injury (TBI) before and after AT.

Case

This study, no. 0163/09, was approved by the Ethics Committee for the Analysis of Research Projects (CAPPesq) of the Hospital das Clinicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo in 2009.

A 49-year old man, complaining that he could not understand people when they spoke, sought the Audiology service of Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo to undergo auditory testing. In the anamnesis, the patient reported that he began to have difficulty understanding speech when he was knocked over in 1997. The report issued by the hospital on the day of the accident describes an occipital subgaleal hematoma D, acute frontal subdural hematoma E and otorrhage E. In the right hemisphere there was a longitudinal base fracture with polytrauma. The neurological examination showed a Glasgow scale score of 12, a state of aphasia and psychomotor agitation. Subsequent neurological examinations (2000) reported permanent debility in the senses of hearing and smell linked to the traumatic event. The patient reports that he has not had any type of rehabilitation therapy since the accident.

The audiological tests applied included audiometry, immittance measures, behavioral tests of central auditory processing, and the measurement of the P300 component of the LAEPs (Long Latency Auditory Evoked Potentials). A two-channel audiometer (GSI 61; Grason Stadler) was used for audiometry, and a GSI 33 middle ear analyzer (Grason Stadler) was used for immittance measurements. Electrophysiological procedures were carried out using a Bio-logic Navigator Pro. To analyze the latency and amplitude of the P300 wave, click stimuli were presented at 70 dB HL at a rate of 1.1/sec.

The audiometric assessment revealed mild neurosensory hearing loss with descendent configuration. All auditory processing tests were performed at 40 dB SL from the average frequencies of 500, 1000 and 2000 Hz. The auditory processing tests showed a moderate disorder with impairment of the following abilities: figure-ground to linguistic sounds (PSI and SSW), temporal pattern (Frequency Pattern Sequence) and verbal memory. Thus, the auditory training was prescribed for rehabilitate the abilities altered and later reassessment.

Language was also assessed using the following tests: Boston Test, MAC Battery, TROG protocol, Token Test, and the working memory test. The patient's performance was below that expected in tasks of graphic and oral comprehension, figurative or non-literal language and alteration of working memory. The patient remains on a waiting list for language rehabilitation.

The AT took place in an acoustic cabin for 8 sessions of 40 minutes each. The difficulty level of the AT program was manually set for each test and session to maintain a success/failure rate of approximately 70/30%.4

Before and after the training, cognitive functions were also investigated through the application of a Brief Cognitive Battery.5 The results showed performance below the expected level in some tasks, such as verbal fluency and incidental memory.

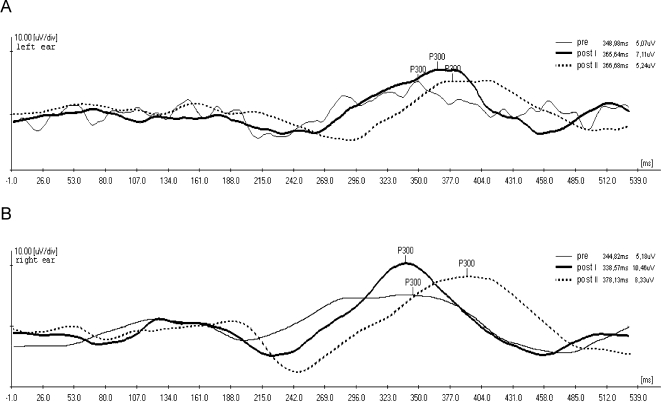

After 8 sessions of auditory training, the patient underwent audiological and cognitive assessments once more (Post-training 1). The patient reported an improvement in the ability to understand speech, and the results showed performance improvements in most of the applied behavioral auditory tests (Table 1). Improvements were also noted in the P300 wave morphology, with an increase in amplitude in both ears and a decrease in latency in the right ear (Figure 1). In addition, an improvement in performance was observed in 5 of the 7 cognitive abilities analyzed, also shown in the Table 1.

Table 1.

Auditory processing and cognitive abilities pre- and post-treatment.

| Behavior Tests | Pre-training | Post-training 1 | Post-training 2 |

| Auditory Audiometry | |||

| SSW | RE 80%, LE 70% | RE 90%, LE 85% | RE 97%, LE 85% |

| PSI | RE 40%, LE 60% | RE 80%, LE 70% | RE 100%, LE 70% |

| Speech in Noise | RE 84%, LE 72% | RE 84%, LE 84% | RE 80%, LE 84% |

| Frequency Pattern | 75% | 95% | 85% |

| Verbal memory | 67% | 100% | 67% |

| Non-verbal memory | 33% | 33% | 67% |

| Cognitive | |||

| Delayed Recall | 70% | 100% | 70% |

| Immediate memory | 80% | 90% | 80% |

| Recognition | 90% | 100% | 90% |

| Incidental memory | 50% | 90% | 70% |

| Learning | 100% | 100% | 90% |

| Clock Drawing test | 90% | 90% | 90% |

| Fluency test | 10 words | 16 words | 18 words |

Improvement with stable behavior; SSW: staggered spondaic words; PSI: pediatric speech intelligibility;

RE: right ear; LE: left ear.

Figure 1.

Results of the P300 Long-Latency Evoked Auditory, test in both ears, pre- and post-auditory training. A: LEFT EAR, PRE-TRAINING: latency 348,98 ms, amplitude 5,07 µV; POST-TRAINING I: latency 365,64 ms, amplitude 7,11 µV; POST-TRAINING II: latency 366,68 ms, amplitude 5,24 µV. B: RIGHT EAR, PRE-TRAINING: latency 344,82, amplitude 5,18; POST-TRAINING I: latency 338,57, amplitude 10,46; POST-TRAINING II: latency 378,13 ms, amplitude 8,33 µV.

To investigate whether any consolidation of learning occurred, a re-assessment was performed after approximately 4 months (Post-training 2). Concerning auditory processing, the patient maintained a similar performance level on most of the tests on which he had shown a post-training improvement (SSW, PSI, Speech with Noise) and a slight drop in performance on the Frequency Pattern and Memory for Oral Sounds tests (Table 1). In the cognitive tests, a slight drop in performance occurred on most of the tests on which the patient had shown an improvement (Delayed Recall, Immediate and Incidental Memory, Recognition). The values obtained in the P300 wave morphology also worsened, with a reduction in amplitude and an increase in latency observed in both ears (Figure 1).

DISCUSSION

Before analyzing the data, it is important to note some limitations of this study. The patient had not been recently subjected to an image exam to investigate the presence of changes that should have taken place since the injury considering the plasticity of the nervous system, and no auditory exam was performed prior to the TBI. Therefore, it is not possible to assume that the peripheral hearing loss occurred previous to the lesion.

Auditory processing disorders can occur as the result of a TBI when there is a lesion in primary and secondary auditory cortical areas.5 Regarding peripheral alterations, the type of fracture is correlated with hearing loss, with conductive hearing loss more common in cases of longitudinal fractures and sensorineural hearing loss more common among patients with transverse fractures.6

In the present study, the patient has a neurosensory hearing loss that would indicate that it is not associated with the TBI, considering that the patient suffered a longitudinal fracture. However, the characteristics of the patient's complaints were highly similar to those of auditory processing disorder (difficulty in understanding speech), confirming the importance of investigating and rehabilitating the patient's auditory skills.

The results of the behavioral auditory tests obtained post-AT demonstrate the efficacy of the auditory training for the rehabilitation of the patient's auditory abilities, as shown by the means of the performance on the first post-training tests. This result corroborates several research studies that also demonstrated the efficacy of this method in rehabilitating auditory processing disorders.2,3 Moreover, electrophysiological evaluations enabled us to monitor the changes that took place in the central nervous system after the training. These adaptations are indicated by the changes in wave morphology, which in this study were mostly related to an increase in amplitude corresponding to the increase in both neural synchrony and the number of neurons responding to the sensory information. Therefore, we suggest that the enhancement of the P300 value could be related to a positive change in some area of auditory damage, demonstrating the neurophysiological influence of auditory training following TBI. Note that we did not investigate the hypothesis that the test-re-test learning influenced the post-training improvement. However, several studies have already shown that there is no significant difference in performance in these same tests when applied over short intervals of time (months), provided that each test yields reliable results.7-9

Post-training improvements were also found in some tests of cognitive abilities, demonstrating that the learning of auditory abilities was probably generalized to cognitive abilities as well. This improvement demonstrates that even a unimodal training regimen aimed at improving the perception of acoustic signals can yield improvements in central processes (“top-down processes”) involving multimodal tasks. Thus, if the relationship between the processes studied here (auditory abilities and cognition) truly exists, this type of training could be employed as an alternative method for the rehabilitation of other alterations that affect cognitive processes, such as dementia and psychiatric disorders.

The retention of the post-training learning was also investigated. Whereas the improvement in auditory skills persisted, suggesting the consolidation of the learning, the cognitive tests and the P300 performance worsened following the initial post-training test. No previous studies have investigated the consolidation of post-training learning in TBI patients. Other studies have addressed the effect of the intensiveness of the training. According to Wright and Sabin,10 as yet there is no general agreement about the length of training deemed sufficient for this consolidation process to occur. The current study adopted the same training protocol (8 sessions) as that used extensively and with efficacy in children with auditory processing disorders. It is possible that cases involving TBI require more sessions for the phenomenon of consolidation to occur. This hypothesis should be investigated further in later studies.

To conclude, these results showed that AT induced plasticity, with an improvement in auditory abilities and a generalization of that improvement to cognitive abilities, but there was no consolidation of the improvement of the auditory and cognitive skills after 4 months. Future research is required to investigate the length and intensity of training required to promote the consolidation of learning in such cases.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Analysis of Research Projects (CAPPesq) of the Hospital das Clínicas/Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo on 2009, Research Protocol no. 0163/09.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chermak GD, Musiek FE. Auditory training: principles and approaches for remediating and managing auditory processing disorders. Semin Hear. 2002;23:297–308. 10.1055/s-2002-35878 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alonso R, Schochat E. A eficácia do treinamento auditivo formal em crianças com transtorno de processamento auditivo (central): avaliação comportamental e eletrofisiológica. Brazilian journal of otorhinolaryngology. 2009;75:726–32. doi: 10.1016/S1808-8694(15)30525-5. 10.1590/S1808-86942009000500019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zalcman TE, Schochat E. A eficácia do treinamento auditivo formal em indivíduos com transtorno de processamento auditivo. Rev. Soc. Bras. Fonoaudiol. 2008;12:310–4. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Musiek FE, Schochat E. Auditory training and central auditory processing disorders: a case study. Semin Hear. 1998;19:357–66. 10.1055/s-0028-1082983 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vitiello APP, Ciríaco JGM, Takahashi DY, Nitrini R, Caramelli P. Avaliação cognitiva breve de pacientes atendidos em ambulatórios de neurologia geral. Arq. Neuro-Psiquiatr. 2007;65:299–303. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2007000200021. 10.1590/S0004-282X2007000200021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Musiek FE, Baran JA, Shinn J. Assessment and remediation of an auditory processing disorder associated with head trauma. J Am Acad Audiol. 2004;15:117–32. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.15.2.3. 10.3766/jaaa.15.2.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jerger S. Evaluation of central auditory function in children. In: Keith R W, editor. Central auditory and language disorders in children. San Diego: College-Hill Press; 1982. pp. 30–60. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frasca MFSS. Dissertation (mestrado) São Paulo: Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo; 2005. Processamento auditivo em teste e reteste: confiabilidade da avaliação. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keith RW. Developmental and standardization of SCAN-A test for auditory processing disorders in adults. J Am Acad Audiol. 1995;6:286–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wright BA, Sabin AT. Perceptual learning: how much daily training is enough. Exp Brain Res. 2007;180:727–36. doi: 10.1007/s00221-007-0898-z. 10.1007/s00221-007-0898-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]