Abstract

Production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) induces oxidative damages, decreases cellular energy conversion efficiencies, and induces metabolic diseases in humans. During respiration, cytochrome bc1 efficiently oxidizes hydroquinone to quinone, but how it performs this reaction without any leak of electrons to O2 to yield ROS is not understood. Using the bacterial enzyme, here we show that a conserved Tyr residue of the cytochrome b subunit of cytochrome bc1 is critical for this process. Substitution of this residue with other amino acids decreases cytochrome bc1 activity and enhances ROS production. Moreover, the Tyr to Cys mutation cross-links together the cytochrome b and iron-sulfur subunits and renders the bacterial enzyme sensitive to O2 by oxidative disruption of its catalytic [2Fe-2S] cluster. Hence, this Tyr residue is essential in controlling unproductive encounters between O2 and catalytic intermediates at the quinol oxidation site of cytochrome bc1 to prevent ROS generation. Remarkably, the same Tyr to Cys mutation is encountered in humans with mitochondrial disorders and in Plasmodium species that are resistant to the anti-malarial drug atovaquone. These findings illustrate the harmful consequences of this mutation in human diseases.

Keywords: Bioenergetics, Cytochrome b, Cytochrome c, Enzyme Mechanisms, Oxygen Radicals, Oxygen Sensitivity and Oxidative Stress, Bacterial Complex III, Cytochrome bc1 and ROS, Mitochondrial Diseases, Respiration and Bioenergetics

Introduction

In most organisms, the ubiquinol:cytochrome c oxidoreductase (cytochrome bc1 or complex III) is a central enzyme for ATP production through oxidative phosphorylation that relies on the proton motive force (ΔμH+) generated by the respiratory chain (1). Production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) leads oxidative damages of cellular components and in eukaryotes induces apoptosis (2, 3). Most cellular ROS are thought to emanate from the respiratory NADH:dehydrogenase (i.e. complex I) and cytochrome bc1 (see Fig. 1a for Rhodobacter capsulatus structure) under compromising physiological conditions (4, 5). Cells use antioxidant enzymes (e.g. superoxide dismutase or glutathione peroxidase) to prevent oxidative damages, but upon extensive ROS generation, harmful damage occurs. Indeed, cellular redox homeostasis, regulated by the rate of electron flow through the respiratory chain and O2 availability, is tightly coupled with the global metabolism (4, 5). For example, recent studies show that cytochrome bc1 is involved in stabilization and activation of hypoxia-induced factors like HIF-1α by mitochondria-generated ROS under hypoxic conditions (6, 7).

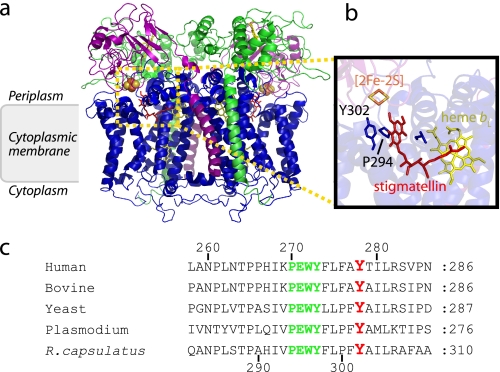

FIGURE 1.

Structure of cytochrome bc1 and location of the conserved Tyr302 of cytochrome b. a, the three-dimensional structure of bacterial dimeric cytochrome bc1 bound with Stg thought to mimic QH2 (Protein Data Bank code 1ZRT) is shown. The catalytic subunits cytochrome b, cytochrome c1, and the iron-sulfur protein are shown in blue, green, and purple, respectively. Hemes are shown as yellow sticks, the [2Fe-2S] cluster are yellow and orange spheres, and the Qo site inhibitor Stg is in red. b, a Qo site close-up view, with the iron-sulfur protein and its [2Fe-2S] cluster (yellow sticks) and cytochrome b and its conserved Tyr302, together with Pro294 residue of the PEWY sequence, is depicted. c, sequence alignment of R. capsulatus (or R. sphaeroides) cytochrome b residues around the conserved tyrosine 302 (278 in human and bovine, 268 in Plasmodium, and 279 in yeast) is shown in red, and the conserved PEWY motif is in green. Human, bovine, yeast, Plasmodium, and R. capsulatus refer to Homo sapiens (NCBI protein database accession number P00156), Bos taurus (accession number P00157), Saccharomyces cerevisiae (accession number P00163), P. yoelii (accession number AAC25924), and R. capsulatus (accession number P08502) cytochrome bc1, respectively.

Mitochondrial DNA mutations are known causes of clinical syndromes (e.g. LHON, Pearson syndrome, and exercise intolerance) or provide predisposition for inherited and common diseases (e.g. aging, cardiomyopathy, cancer, diabetes, and neurodegenerative diseases) (8, 9). Mutations in mitochondrial or nuclear DNAs associated with mitochondrial fission and fusion (10), ascribed to ROS generation, lead to progressive dysfunction of mitochondria and loss of energy efficiency (11). For example, the Tyr to Cys mutation at position 278 (position 302 in R. capsulatus; see Fig. 1b) of cytochrome b of human mitochondrial cytochrome bc1 (complex III) causes severe exercise intolerance and “multi-system disorder” (12). Remarkably, the same mutation in this conserved residue (Fig. 1c) is also encountered in cytochrome bc1 of malarial parasites (e.g. Plasmodium falciparum or Plasmodium yoelii) that are resistant to the antimalarial drug atovaquone (13, 14). These clinical findings highlight that specific amino acids of cytochrome bc1 are critical for human mitochondrial diseases (12, 15), for resistance of parasites to therapeutic agents (16), and for catalytic activity of the enzyme in bacteria (17) and yeast (18, 19), yet our understanding of the mechanisms underlying these disparate defects remains elusive.

Cytochrome bc1 oxidizes reduced quinone (QH2)4 via an unstable semiquinone intermediate at a catalytically active (i.e. Qo) site. Its function depends on an elaborate mechanism with two “one-electron” transfer steps, one to a high potential chain (comprising the iron-sulfur protein and cytochrome c1) and another to a low potential chain (formed of the hemes bL and bH of cytochrome b) to generate ΔμH+ across the membrane with minimal energy expenditure (20–22). Several models (23–25) have been proposed to rationalize the efficient and safe occurrence of these electron transfer steps in the presence of O2. However, how the reactive intermediates of the Qo site are shielded from O2 to avoid oxidative damages remains unknown (26). We hypothesized that specific amino acids at the Qo site might provide protective mechanism(s) against oxidative damage while ensuring catalytic efficiency. Using the bacterial enzyme, here we show that mutating a specific Tyr residue of cytochrome b subunit of cytochrome bc1 greatly enhances ROS production. Remarkably, the Tyr to Cys substitution cross-links together the cytochrome b and the iron-sulfur subunits of cytochrome bc1 and renders the bacterial enzyme sensitive to O2 by oxidative disintegration of its catalytic [2Fe-2S] cluster. These findings demonstrate the occurrence of “protective residue(s)” in cytochrome bc1, like this Tyr of cytochrome b that controls ROS generation. They also illustrate how specific mutations on such critical residues cause broad cellular defects extending from human mitochondrial diseases (12) to parasite resistance to therapeutics (16).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bacterial Strains, Growth Conditions, and Genetic Techniques

Escherichia coli and R. capsulatus strains were grown as described earlier (27). Mutations at Tyr302 of R. capsulatus cytochrome b were introduced by using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) with the plasmid pPET1 as a template and appropriate mutagenic primers. The 1.66-kb XmaI-StuI DNA fragment of pPET1 bearing the mutation was exchanged with its counterpart in pMTS1, yielding the plasmids pMTS1:Y302X (where X indicates Ala, Cys, Phe, Ser, or Val), which were crossed into the strain MT-RBC1 lacking cytochrome bc1, as described earlier (27–31). The presence of only the desired mutation was confirmed by DNA sequence analysis of plasmids.

Preparation of Aerobic and Anaerobic Membrane Samples

Aerobic chromatophore membranes were prepared in 50 mm MOPS (pH 7.5), 100 mm KCl, 100 mm EDTA, 1 mm caproic acid, and protein concentrations determined as described earlier (28, 29). For anaerobic membrane samples, an anaerobic chamber (MBraun-USA Inc., Stratham, NH) at 20 °C was used with degassed, argon-flushed buffers containing 5 mm sodium dithionite. The membranes were prepared under argon flushing and stored in gas-tight serum vials with septa (National Scientific Co.). For sulfhydryl alkylation experiments, 100 mm idoacetamide (IAM) or N-ethylmaleimide was added prior to cell disruption.

Biochemical and Biophysical Techniques

Protein samples were solubilized in 62.5 mm Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 4% SDS, 100 mm dithiothreitol, 25% glycerol, and 0.01% bromophenol blue incubated at 60 °C for 10 min, separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and stained with Coomassie Brilliant R-250, and immunoblots were performed using monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies specific for R. capsulatus cytochrome bc1 subunits as described in Ref. 29. Cytochrome bc1 activity was measured using decylbenzo-hydroquinone (DBH2):cytochrome c reductase assay as described in Refs. 27 and 29. For all of the strains, at least three independent cultures were used, three independent measurements per culture were performed, and the mean values ± standard deviations are indicated. Optical difference spectra for b- and c-type cytochromes were recorded, and R. capsulatus cytochrome bc1 was purified and stored at −80 °C as described (28, 29). Light-activated kinetic spectroscopy was performed as described in Ref. 30 using a dual wavelength spectrophotometer. In all cases, the membranes contained 0.3 μm of reaction center as determined by a train of 10 light flashes separated by 50 ms at an Eh of 380 mV, and an extinction coefficient ϵ605–540 of 29 mm−1 cm−1. Transient cytochromes c (at 550–540 nm) and b (at 560–570 nm) reduction kinetics exhibited by membranes resuspended in 50 mm MOPS buffer (pH 7.0), 100 mm KCl, and 100 mm EDTA at an ambient redox potential of 100 mV were monitored. Antimycin A, myxothiazol, and stigmatellin (Stg), inhibitors of cytochrome bc1, were used at 5, 5, and 1 μm, respectively. EPR spectroscopy was performed using a Bruker ESP-300E (Bruker Biosciences), equipped with an Oxford Instruments ESR-9 helium cryostat (Oxford Instrumentation Inc.) as described in Ref. 31. As needed, the membranes (25–30 mg of protein/ml) were reduced by incubation on ice for 10 min with 20 mm ascorbate in the presence or absence of 100 μm Stg or 100 μm famoxadone. Spectra recording conditions were for the [2Fe-2S] cluster: modulation frequency, 100 kHz; microwave power, 2 milliwatts; sample temperature, 20 K; microwave frequency, 9.443 GHz; modulation amplitude, 12 G, and for the b hemes: modulation frequency, 100 kHz; sample temperature, 10 K; microwave frequency, 9.59 GHz; modulation amplitude, 10 G.

Superoxide Measurements

The rate of superoxide production was determined using manganese-SOD-sensitive and Stg-sensitive cytochrome c reduction assays (32). First, in the presence and absence of manganese-SOD (150 units/ml SOD from Sigma), (−SOD/−Stg) and (+SOD/−Stg) cytochrome c reduction rates were determined by using DBH2:cytochrome c reductase assays (27, 29). Then (+SOD/+Stg) and (−SOD/+Stg) rates of cytochrome c reduction were determined using membranes inhibited by 10 μm Stg to obtain cytochrome bc1-specific rates. The amounts of superoxide produced independently of cytochrome bc1 were excluded by subtracting from (−SOD/+Stg) the (+SOD/+Stg) values. The absence of enhancement of ROS production by the addition of antimycin A in the presence of Stg provided an extra control for cytochrome bc1-independent ROS generation. The ROS that is specifically produced by the cytochrome bc1 was then determined by subtracting from [(−SOD-Stg) − (+SOD-Stg)] the [(−SOD+Stg) − (+SOD+Stg)] values. In this way, of the total cytochrome c reduction rates observed, only the portion that is sensitive to Stg and to manganese-SOD was attributed to superoxide originating specifically from cytochrome bc1 Qo site. Antimycin A-induced ROS productions were measured in similar ways except that 20 μm antimycin A was added.

The cumulative amounts of superoxide production were measured via H2O2 formation using the Amplex® Red-horseradish peroxidase method (Molecular Probes, Inc.). As above, DBH2:cytochrome c reduction assay mixtures with and without Stg were supplemented with 50 μm Amplex Red, 150 units/ml manganese-SOD and 0.1 units/ml of horseradish peroxidase and incubated at room temperature for 1 min. The amount of the fluorescent resorufin formed from Amplex Red at the end of the incubation period was measured using a PerkinElmer Life Sciences LS-5B luminescence spectrophotometer and 530- and 590-nm excitation and emission wavelengths, respectively. Fluorescence production was linear during the incubation period, and the amount of H2O2 production was calibrated using the standards provided in the Amplex Red kit. Of the total amounts of H2O2 produced, only the portions that were sensitive to Stg were considered as superoxide generated by cytochrome bc1. Antimycin A-induced superoxide productions were measured in the same way except that 20 μm antimycin A was added to the assay mixture (29).

Mass Spectrometry Analyses

SDS-PAGE samples were excised and subjected to in-gel digestions, whereas purified cytochrome bc1 samples were digested in-solution using trypsin and, as needed, GluC, as described (33–35). Peptides were analyzed with a Thermo LCQ Deca XP+ MS/MS spectrometer coupled to a LC Packings Ultimate Nano HPLC system controlled by Thermo Xcalibur 2.0 software. Thermo Bioworks 3.3 software was used to perform SEQUEST searches against the R. capsulatus protein database as described earlier (33–35). The results were filtered using standard values for Xcorr (1.5, 2.0, and 2.5 for m/z of +1, +2, and +3, respectively) and ΔCN ≥ 0.1, and relevant spectra were inspected manually for validity of the assignments.

Chemicals

All of the chemicals were as described earlier (29).

RESULTS

Mutation of Cytochrome b Tyr302 to Cys Renders Cytochrome bc1 Activity Sensitive to O2

The structures of cytochrome bc1 (36–38) reveal that the conserved Tyr302 residue of R. capsulatus cytochrome b (Tyr278 and Tyr279 in human or bovine and yeast numberings, respectively) is near the Qo site, where QH2 oxidation occurs (Fig. 1, b and c). This residue is part of the docking niche of the iron-sulfur protein subunit of the enzyme and is H-bonded to the backbone of a Cys residue of this subunit to position correctly its [2Fe-2S] cofactor at the Qo site. The role of this Tyr residue on QH2 oxidation has been described earlier using Rhodobacter sphaeroides cytochrome bc1 mutants where Tyr302 was substituted with Phe, Leu, Gln, and Gly) (17). We had also examined its role during our studies related to malarial atovaquone resistance (16). A surprising finding was that in the closely related R. capsulatus species, the Y302C mutant exhibited robust anoxygenic (−O2) photosynthetic growth that absolutely requires an active cytochrome bc1, whereas routinely prepared membranes from aerobically (+O2) grown cells had poor cytochrome bc1 activity (16) (Fig. 2a). Because the Y302C mutant has not been examined earlier (17), to further explore this observation, we studied the effects of R. capsulatus Y302X (where X indicates Ala, Cys, Phe, Ser, or Val) substitutions on cytochrome bc1 activity. When cells were grown and membranes were prepared in the presence of O2, all of the mutants contained normal amounts of cytochrome b, cytochrome c1, and iron-sulfur protein subunits as indicated by optical difference spectra and SDS-PAGE analyses (Fig. 2, b and c). They also responded normally to the Qo site inhibitors Stg and famoxadone (Table 1). Thus, like the homologous R. sphaeroides (17) or yeast (18, 19) mutants, all R. capsulatus Y302X mutants also assembled cytochrome bc1, but the Y302A, Y302S, and Y302C substitutions had comparatively lower activities than the Y302V and Y302F substitutions using membranes prepared in air from aerobically grown cells (Fig. 2a). Remarkably, however, these activities changed when cells were grown by anoxygenic photosynthesis, and the membranes were prepared in the absence of O2. Wild type cells showed little decrease under −O2 conditions with respect to cytochrome bc1 activity (∼70% of +O2 activity, possibly because of total membrane protein content changes and because of anaerobic preparations). A similar pattern was also observed with Y302F and Y302V substitutions. In contrast, the Y302A, Y302S, and Y302C mutants displayed an opposite pattern with increased cytochrome bc1 activity under −O2 as compared with +O2 conditions (Fig. 2a). In particular, the Y302C substitution showed a marked enhancement (∼2–3-fold increase from +O2 to −O2 conditions), but as expected, it did not reach wild type activity levels because of its partially defective Qo site (like all Y302X mutants). When corrected for the corresponding wild type activities observed under +O2 and −O2 conditions (15 and 56% of wild type, respectively), the Y302C enhancement appears even more (∼3–4-fold) pronounced.

FIGURE 2.

Cytochrome bc1 activities of WT and Y302X mutants in the presence and absence of O2 and biochemical properties of WT and Y302X mutant variants. a, cells were grown, and membranes were prepared, either in the presence (+O2, filled bars) or absence (−O2, open bars) of air. In each case, cytochrome bc1 (Cyt bc1) activities are expressed as percentages of the wild type activity determined under +O2 conditions. Wild type activities were 3.5 and 2.7 μmol of cytochrome c reduced min−1 mg of membrane protein−1 under +O2 and −O2 conditions, respectively. The mean values ± standard deviations are shown. Variations in the wild type cytochrome bc1 activities under +O2 and −O2 conditions derive from the changing total membrane protein contents and different sample preparation methods and are not to be compared directly. b, dithionite-reduced (black) or ascorbate-reduced (gray) minus ferricyanide-oxidized optical difference spectra of aerobically prepared membrane fractions (0.4 mg of total proteins) from +O2 grown WT and Y302X mutant strains. The 550- and 560-nm peaks correspond to the cytochromes c and b, respectively. c, SDS-PAGE and Western blot analyses of the same membrane fractions (50 μg of total proteins) from WT and Y302X mutant cells. The cytochrome bc1-deficient strain MT-RBC1 was used as a negative control, and cytochrome b and iron-sulfur protein subunits were detected by Western blot analysis using monoclonal (a-cyt b) and polyclonal (a-Fe/S) antibodies, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Properties of Y302X mutants under aerobic conditions

| Strain | Wild type | Y302A | Y302C | Y302F | Y302S | Y302V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relevant phenotypea | Ps+ | Ps+ | Ps+ | Ps+ | Ps+ | Ps+ |

| Membrane protein content (mg/ml) | 13.4 ± 0.7d | 12.3 ± 0.5 | 13.4 ± 0.9 | 14.3 ± 0.6 | 15.5 ± 1.8 | 12.7 ± 0.5 |

| Membrane cytochrome b content (nmol/mg)b | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 2.7 ± 0.2 |

| Membrane cytochrome c content (nmol/mg)b | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.2 |

| Relative cytochrome c reductase activity (%)c | ||||||

| No inhibitor | 100 | 15.4 ± 1.4 | 14.8 ± 2.9 | 77.4 ± 8.4 | 4.0 ± 1.3 | 41.6 ± 4.3 |

| Stigmatellin | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 |

| Myzothiazol | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 5.6 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 4.4 ± 0.4 | 1.8 ± 0.1 |

| Famoxadone | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 |

| Antimycin A | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 1.0 | 3.7 ± 1.2 | 9.7 ± 1.9 | 7.7 ± 3.0 |

a Ps+ refers to anaerobic photosynthetic (−O2) growth ability.

b Cytochromes c and b contents of membranes were determined using optical redox difference spectra.

c Cytochrome bc1 activity refers to the 2,3-dimethoxy-5-methyl-6-decyl-1,4-benzohydroquinone (DBH2): cytochrome c reductase activity expressed as a percentage of the wild-type activity, which was approximately 3.5 μmol of cytochrome c reduced min−1 mg of protein−1 of membranes prepared in the presence of air using aerobically grown cells. Each assay was conducted at least in triplicate.

d The data are the means ± standard deviations.

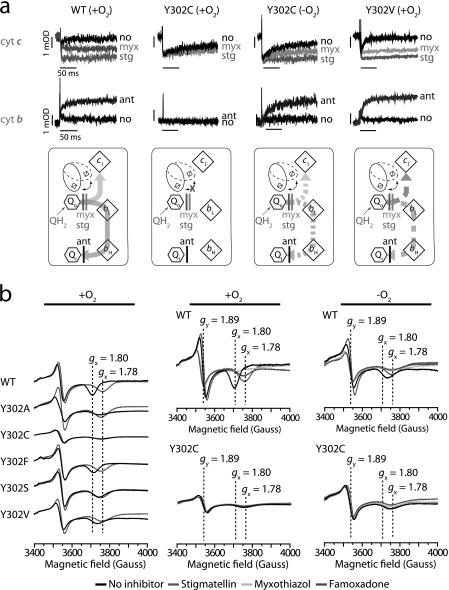

Performance of light-activated, single-turnover cytochrome c and b reduction kinetics (30) established that the O2-sensitive catalytic step in the Y302C mutant was the bifurcated electron transfer event during QH2 oxidation. Although rapid reduction kinetics of cytochromes c and b were seen with +O2 membranes of aerobically grown wild type and Y302V mutant, they were undetectable with similar +O2 Y302C samples (Fig. 3a, upper and lower traces, respectively; see also the schematic drawings underneath of them). However, rapid kinetics were readily seen with Y302C membranes prepared in the absence of O2 using anaerobically grown cells, demonstrating that Qo site catalysis became O2-sensitive in Y302C mutant.

FIGURE 3.

Cytochrome bc1 Qosite activity is O2-sensitive in the Y302C variant. a, light-activated cytochrome (cyt) c and b reduction kinetics exhibited by membranes containing native (WT) or Y302C and V variants of cytochrome bc1, prepared in the presence (+O2) or absence (−O2) of oxygen, were monitored by optical kinetic spectroscopy. The membranes contained 0.3 μm of reaction center determined using the extent of its photo-oxidation (605–540 nm), and cytochrome c (550–540 nm) and b (560–570 nm) reduction kinetics were monitored in the absence of inhibitors (no) and the presence of cytochrome bc1 Qi site (5 μm antimycin A, ant) or Qo site (5 μm myxothiazol, myx; 1 μm Stg) inhibitors. Electron transfer steps between the cofactors of cytochrome bc1 (light and dark arrows for the high and low potential chain cofactors, respectively), and the associated movement of the iron-sulfur protein (black, double-headed arrow) are shown schematically below the kinetic traces. Solid and dotted arrows refer to fast (submillisecond) and slower (millisecond) electron transfer rates exhibited by the native and mutant variants, respectively. b, left column, EPR spectra of the iron-sulfur subunit [2Fe-2S] cluster of native (WT) and Y302A, Y302C, Y302F, Y302S, and Y302V variants of cytochrome bc1. The spectra were obtained using ascorbate reduced +O2 membranes (25 mg of total proteins/ml) in the absence (black) and presence of 100 μm Stg (gray). Middle and right columns, effect of O2 on the EPR spectra of the iron-sulfur subunit [2Fe-2S] cluster of native (WT) and Y302C variant cytochrome bc1. The vertical dotted lines indicate the gy (1.89, no inhibitor) and gx (1.78 with inhibitor; 1.80 without inhibitor) transitions of the iron-sulfur protein [2Fe2S] cluster. The spectra were obtained using membranes prepared in +O2 and −O2 conditions in the absence (black) and presence of 100 μm of Qo site inhibitors (Stg, famoxadone or myxothiazol).

Y302C Substitution Induces Oxidative Disruption of the [2Fe-2S] Cluster of Cytochrome bc1

Because the cytochromes b and c contents of all Y302X mutants were similar (Table 1), EPR spectroscopy was used to examine their iron-sulfur protein [2Fe-2S] cluster (31). The mutants showed altered EPR spectra and gx and gy values different from those (1.80 and 1.89, respectively) of the wild type, revealing that substitution of Tyr302 perturbed the Qo site and the environment of the [2Fe-2S] cluster (Fig. 3b, left panel). When samples prepared under +O2 and −O2 conditions using appropriately grown cells were compared, drastic changes were seen with the Y302C mutant in respect to the iron-sulfur protein [2Fe-2S] cluster amounts, as reflected by the EPR gy signals (Fig. 3b, middle and right panels). For the wild type, EPR spectra of the [2Fe-2S] cluster of −O2 or +O2 grown cells were similar to one another (and the observed amplitudes of the gx and gy signals were in agreement with the respective cytochrome bc1 activities shown in Fig. 2a). On the other hand, the amplitudes of the iron-sulfur protein [2Fe-2S] cluster gy and gx signals of Y302C samples were very low under +O2, but significantly higher under −O2 conditions (Fig. 3b, middle and right bottom panels). Based on the gy signal amplitudes, +O2 and −O2 grown Y302C cells contained ∼14 and 53%, respectively, of the iron-sulfur protein [2Fe-2S] cluster as compared with the wild type enzyme (31). These percentage values roughly match the corresponding relative enzyme activities for Y302C (Fig. 2a, at 15 and 56% of wild type activities) obtained for +O2 and −O2 conditions, suggesting that a loss of cytochrome bc1 activity correlates with a loss of the [2Fe-2S] cluster in Y302C mutant. This finding was unexpected, because the [2Fe-2S] cluster of wild type cytochrome bc1 has a high redox midpoint potential, and its oxidative disruption does not occur readily upon exposure to air (31, 39).

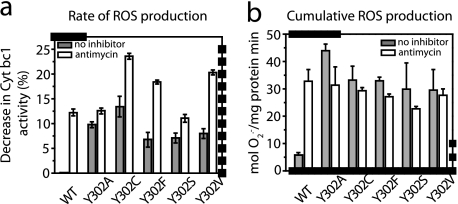

Loss of Tyr302 Enhances ROS Generation During Qo Site Catalysis

Native cytochrome bc1 produces insignificant amounts of ROS except under conditions that interfere with bifurcated electron transfer at the Qo site (e.g. in the presence of inhibitors like antimycin A or high membrane potential, Δψm) (22, 26, 32, 40). The unusual oxygen sensitivity of the [2Fe-2S] cluster of the iron-sulfur protein in Y302C seen above (i.e. the decreased gy signal in Fig. 3b) led us to examine ROS production by the Y302X mutants. Manganese-SOD-sensitive cytochrome c reduction assays were used to monitor Stg-sensitive (i.e. cytochrome bc1-specific) ROS generation. Under these conditions, native cytochrome bc1 produced detectable amounts of ROS exclusively upon exposure to antimycin A (Fig. 4a, observed as a decrease of cytochrome bc1 activity by ∼12% upon manganese-SOD addition). In contrast, all of the Y302X mutants produced large amounts of ROS (6–13% decrease of cytochrome bc1 activity upon manganese-SOD addition) even in the absence of antimycin A (Fig. 4a). In all cases, this production was further enhanced (to ∼10–23%) by the addition of antimycin A.

FIGURE 4.

Rate of superoxide production, and cumulative superoxide production, by native (WT) and Y302X variants of cytochrome bc1 in the absence and presence of antimycin A. a, rate of superoxide production by native (WT) and Y302X = Ala, Cys, Phe, Ser, or Val variants of cytochrome bc1 in the absence (filled bars) and presence (open bars) of antimycin A was monitoring via the manganese-SOD-induced decrease of DBH2:cytochrome c reduction rates. In all cases, cytochrome c reduction rates were corrected for Stg-insensitive (i.e. cytochrome bc1-independent) rates, and the difference observed between the corrected cytochrome c reduction rates seen in the absence and presence of manganese-SOD was attributed to ROS generated by cytochrome bc1 Qo site, as described under “Experimental Procedures” and Fig. 1 legend. b, cumulative superoxide production was determined using membranes prepared in the presence of air from aerobically grown cells, incubated for 1 min under the DBH2:cytochrome c reduction assay conditions, and accumulated amounts of ROS produced were measured by the Amplex red assay. In this assay, H2O2 formation in the presence of excess manganese-SOD is coupled to horseradish peroxidase-mediated Amplex Red conversion to resorufin. Of the total amounts of H2O2 produced, only the portions that were sensitive to Stg are considered as superoxide generated by cytochrome bc1.

In addition, cumulative ROS production by Y302X mutants was also tested using Amplex Red-based assays. The data demonstrated that Y302X mutants produced ROS in the absence of antimycin A at amounts similar to those seen with a native enzyme inhibited with antimycin A (Fig. 4b). Thus, loss of Tyr302 led to electron leakage from the Qo site to O2 in a way independent of antimycin A effect. This finding indicated that Tyr302 of cytochrome b has a protective role in suppressing ROS generation mediated by cytochrome bc1 Qo site.

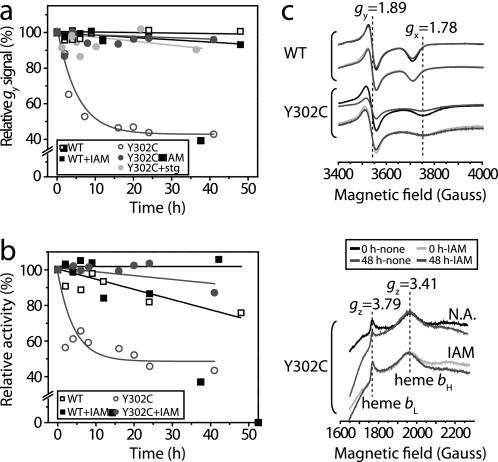

Arresting Qo site Catalysis, or Alkylating Cys-302, Protects the [2Fe-2S] Cluster against Oxidative Damage

Although all Y302X mutants produced ROS, oxidative disintegration of the [2Fe-2S] cluster was observed only with Y302C mutation (Fig. 3b). We examined −O2-grown Y302C cells after treatment with Stg to inactivate cytochrome bc1 Qo site prior to O2 exposure to elucidate how the [2Fe-2S] cluster was inactivated (Fig. 5a). Monitoring the Y302C [2Fe-2S] cluster as a function of exposure time to O2, using the EPR gy signal, revealed that the [2Fe-2S] cluster of uninhibited Y302C decreased by 50% of its initial value in 50 h of exposure to O2, whereas Stg-treated samples showed no effect. Thus, inhibiting Qo site catalysis and burying the iron-sulfur protein head domain into cytochrome b surface prevented oxidative disruption of cytochrome bc1 [2Fe-2S] cluster in Y302C mutant.

FIGURE 5.

Qo site inhibitor Stg, or alkylating reagents, protects the iron-sulfur protein [2Fe-2S] cluster of cytochrome bc1 in the Y302C variant against oxidative damage. a and b, the gy signal amplitude of the iron-sulfur protein [2Fe-2S] cluster (a) and cytochrome bc1 activity in cells grown and membrane samples prepared under −O2 conditions, with or without 100 μm Stg as a Qo site inhibitor, and with or without 100 mm IAM as an −SH alkylating reagent (b), were monitored as a function of exposure time to O2. c, EPR spectra of the iron-sulfur protein [2Fe-2S] cluster and cytochrome b hemes (bL and bH) in native (WT) and Y302C variant of cytochrome bc1. For EPR spectroscopy of the [2Fe-2S] cluster or hemes bL and bH, membranes were ascorbate reduced (top panel) or air oxidized (bottom panel), respectively.

Because no cysteine residue is present in R. capsulatus cytochrome b (41), we suspected that the newly gained thiol group in Y302C mutant might be responsible for the oxidative disruption of the [2Fe-2S] cluster. We treated −O2-grown Y302C cells with IAM to alkylate the thiolate anion at position 302 and monitored the [2Fe-2S] cluster disintegration by EPR gy signal as a function of exposure time to O2. Upon exposure to air, untreated Y302C lost the [2Fe-2S] cluster gy signal and the cytochrome bc1 activity during the initial 50 h, whereas IAM-treated membranes retained ∼80% of both of these features (Fig. 5, a and b). EPR spectra of the same samples exhibited no significant variations with respect to hemes bL and bH amounts, which were used as internal controls via their EPR gz transitions (Fig. 5c). Upon extension of the exposure time to O2 up to ∼250 h, the gy signal amplitude of untreated Y302C decreased to 30%, but IAM-treated membranes retained ∼70% of their initial levels (data not shown). We noted that the rate of cytochrome bc1 activity loss induced by IAM was more rapid than that of the EPR gy transition, possibly because of inhibitory hindrances inflicted by alkylation of the Y302C residue at the Qo site. Similar to IAM, treatment with the bulkier alkylating reagent N-ethylmaleimide also protected the [2Fe-2S] cluster from oxidative damage, but it induced a more rapid loss of cytochrome bc1 activity (data not shown). We concluded that introduction of a thiol group at position 302 of cytochrome b rendered bacterial cytochrome bc1 O2-sensitive via oxidative disruption of its iron-sulfur protein [2Fe-2S] cluster upon exposure to air.

An Intersubunit Disulfide Bond Inactivates Cytochrome bc1 and Destabilizes Its [2Fe-2S] Cluster

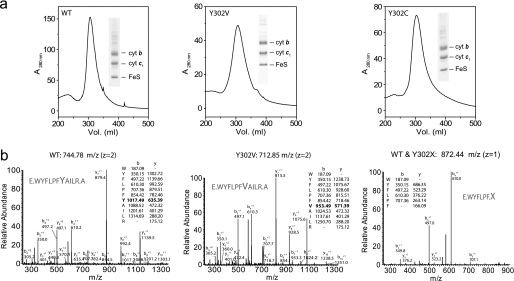

To further investigate the basis of O2 sensitivity described above, native, O2-sensitive Y302C, and O2-tolerant Y302V cytochrome bc1 enzymes were purified and subjected to comparative tandem mass spectrometry analyses. Appropriate protease digestions allowed detection of the peptide 296WYFLPFXAILR306 that encompasses position 302 of cytochrome b (Fig. 6) As expected, this position corresponded to Tyr and Val in the native and Y302V enzymes, respectively, but no such peptide could be detected in Y302C samples, despite searches for ROS-induced cysteine modifications (e.g. sulfenic, sulfinic, or sulfonic acids) (42). However, a shorter peptide (296WYFLPF301) corresponding to a cleavage product immediately before position 302 was observed in all cases (Fig. 6). This suggested that this position might be modified in Y302C mutant enzyme.

FIGURE 6.

Mass spectrometric identification of cytochrome b296WYFLPFXAILR306 peptide that encompasses position 302 in native (WT) and Y302X variants of cytochrome bc1. a, native, Y302V, and Y302C variant cytochrome (cyt) bc1 proteins were purified using Biogel A anionic exchange and Sephacryl S400 chromatography as described previously (29). Purity of the samples was checked by SDS-PAGE/Coomassie Blue staining (insets), and samples were digested in-solution with GluC and trypsin proteases and subjected to nanoLC-MS/MS spectrometry. FeS, iron-sulfur. b, MS/MS fragmentation spectra identified cytochrome b 296WYFLPFYAILR306 (z = 2, Xcorr = 3.18, ΔCN = 0.54) and 296WYFLPFVAILR306 (z = 2, Xcorr = 3.23, ΔCN = 0.64) peptides with the native and Y302V samples, respectively. No such peptide was identified using Y302C variant, although a shorter peptide corresponding to 296WYFLPF301 (z = 1, Xcorr = 1.36, ΔCN = 0.75) (right panel) was observed with all three samples. Only singly charged b and y ions are listed for simplification.

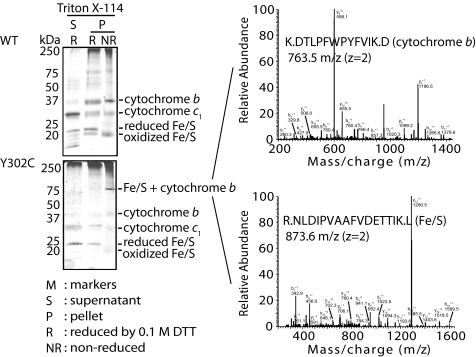

Next, the possibility of an intersubunit disulfide bond formation between the iron-sulfur protein, which is located structurally close to position 302 of cytochrome b (37, 38), was considered. Such an intersubunit cross-link was suspected to be incomplete based on the EPR data related to the destruction of the [2Fe-2S] cluster (Fig. 5a). Purified native and Y302C cytochrome bc1 samples were extracted with Triton X-114 for cytochrome b enrichment and subjected to SDS-PAGE, mass spectrometry, and Western blot analyses. Only with the Y302C samples under nonreducing conditions, a 70-kDa protein band that disappeared upon treatment with DTT was found (Fig. 7, left panel). Using both mass spectrometry (Fig. 7, right panel) and specific antibodies (not shown), the DTT-sensitive 70-kDa band was shown to contain both the 22-kDa iron-sulfur protein and 48-kDa cytochrome b subunits.

FIGURE 7.

Identification of an intersubunit disulfide bond between the iron-sulfur protein and cytochrome b of cytochrome bc1. Proteins of purified native and Y302C variants of cytochrome bc1 were phase-separated by using Triton X-114 to obtain cytochrome b-depleted and -enriched supernatant (S) and pellet (P) fractions, respectively. The samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE/Coomassie Blue staining under nonreducing (NR) and reducing (R) (100 mm DTT) conditions to separate cytochrome bc1 subunits (left panel). The DTT-reducible 70-kDa band, which was seen only with the Y302C sample (NR), was subjected to nanoLC-MS/MS spectrometry. Representative MS/MS fragmentation spectra, identifying in the 70-kDa band the presence of peptides derived from cytochrome b (e.g. DTLPFWPYFVIK with z = 2, Xcorr = 3.44, ΔCN = 0.41) and iron-sulfur protein (e.g. NLDIPVAAFVDETTIK with z = 2, Xcorr = 5.27, ΔCN = 0.73) subunits of cytochrome bc1, are shown (right panel).

Furthermore, extensive MS/MS analyses found additional modified cysteine containing peptide fragments of the iron-sulfur protein (supplemental Fig. S1). The 125WLVMLGVC*THLGCVPMGDK (or 125WLVMLGVCTHLGC*VPMGDK) fragment of the iron-sulfur protein contained a chemically modified Cys by 299 Da (C*), which is compatible with a disulfide bond-linked 302CAI peptide fragment (expected mass of 303 Da) of cytochrome b. Similarly, the 145SGDFGGWFC*PCHGS (or 145SGDFGGWFCPC*HGS) fragment of the iron-sulfur protein contained a chemically modified Cys by 817 Da (C*), which is compatible with a disulfide bond-linked 300PFCAILR peptide fragment (expected mass of 816 Da) of cytochrome b, was found (supplemental Fig. S1). Although these fragments had reliable Xcorr and ΔCN scores, manual inspection of these spectra indicated that these assignments were not unambiguous, only suggesting the occurrence of a disulfide bond involving Cys302 of cytochrome b.

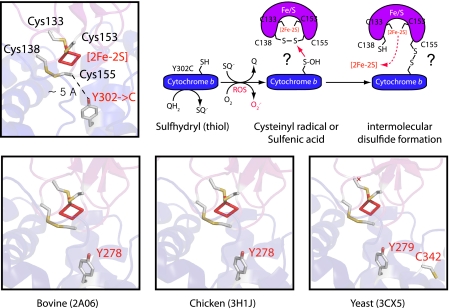

In the native iron-sulfur protein subunit, the Cys138 and Cys155 residues form an intramolecular disulfide bond that increases the redox midpoint potential of the [2Fe-2S] cluster (31, 39). Structures of cytochrome bc1 indicate that this disulfide bond is near the position 302 of cytochrome b when the iron-sulfur protein is docked at the Qo site (37, 38). In R. capsulatus structure (IZRT), the distance between α-Cys153 or α-Cys-155 and O-Tyr302 is ∼5 or 11 Å, respectively. Similarly, in the case of yeast structure (Protein Data Bank code 3CX5), the corresponding distances are ∼4 and 10 Å (supplemental Fig. S2). Cys133 and Cys153 of the iron-sulfur protein are the ligands of the [2Fe-2S] cluster and of the intramolecular disulfide bond forming cysteines (i.e. Cys138 and Cys155), Cys155 is closer to Tyr302 of cytochrome b. In the light of these data, we tentatively propose that in the Y302C enzyme, upon exposure to O2, possibly activated by ROS production via the Qo site, cytochrome b Y302C attacks the Cys138–Cys155 disulfide bond of the iron-sulfur protein to yield an intersubunit disulfide bond between these subunits. The resulting intersubunit disulfide bond then self-inactivates cytochrome bc1, and loss of the intramolecular disulfide bond of the iron-sulfur protein compromises its [2Fe-2S] cluster stability to induce its oxidative disruption (Fig. 8). We emphasize that this attractive proposal should remain hypothetical until the resolution of the structure of Y302C enzyme.

FIGURE 8.

Intersubunit disulfide bond formation induces oxidative inactivation of Y302C cytochrome bc1 in bacteria. Top row, a close-up view of R. capsulatus cytochrome bc1 structure (Protein Data Bank code 1ZRT) showing the regions of cytochrome b (blue) and iron-sulfur protein (purple) at or near the Qo site (left) and a tentative proposal for the formation of an intersubunit disulfide bond between the iron-sulfur protein and cytochrome b leading to oxidative disintegration of the [2Fe-2S] cluster cofactor (red) of cytochrome bc1 is shown. Four conserved cysteine residues (yellow and white sticks) of the iron-sulfur protein (Cys133 and Cys153 acting as ligands of the [2Fe-2S] cluster and Cys138 and Cys155 forming a disulfide bond) are shown together with the conserved Tyr (gray) of cytochrome b substituted with a Cys (Y302C). In the Y302C variant of cytochrome bc1, because of ROS production by the Qo site, the thiol group of cytochrome b Cys302 is thought to reduce the Cys138–Cys155 disulfide bond of the iron-sulfur protein and destabilize the [2Fe-2S] cluster to induce oxidative inactivation of the enzyme. The intersubunit disulfide bond is tentatively proposed to occur between Cys302 and Cys155 (instead of Cys302 and Cys138) because of the shorter distance separating them in the native structure. However, available mass spectrometry data does not discriminate between these two possibilities, and no structure is yet available for R. capsulatus Y302C cytochrome bc1. Bottom row, comparable close-up views of bovine (Protein Data Bank code 2A06), chicken (Protein Data Bank code 3H1J), and yeast (Protein Data Bank code 3CX5) cytochrome bc1 depicting the same region of R. capsulatus cytochrome bc1 shown on the top row. Note that only yeast cytochrome b has an additional cysteine (Cys342) near Tyr279 (bacterial Tyr302 homologue). For detailed comparisons of R. capsulatus (Protein Data Bank code 1ZRT) and yeast (Protein Data Bank code+ 3CX5) cytochrome bc1 structures, see supplemental Fig. S2.

DISCUSSION

Respiratory energy conservation by cytochrome bc1 depends on an elaborate bifurcated electron transfer reaction that occurs in the presence of O2 (22, 43). Unless the catalytic steps associated with oxidation of reduced quinone are compromised, the native enzyme safely carries out this reaction without any ROS production. Various factors, like inhibitors that disable reduction of b hemes (32) or increased Δψm (44) and changes in pO2 (45), trigger ROS production by cytochrome bc1. Serendipitously, studying cytochrome bc1 of a facultative anoxygenic photosynthetic bacterium, R. capsulatus, we found that the Y302C mutant preserved its activity in the absence of O2 but lost it progressively upon exposure to O2 because of oxidative disintegration of its [2Fe-2S] cluster cofactor. This finding illustrates that specific amino acid(s) of cytochrome bc1, like Tyr302 of cytochrome b, might play key roles in preventing undesirable electron leakage to O2 during Qo site catalysis. In the case of R. capsulatus, substituting Tyr302 by other amino acids decreased cytochrome bc1 activity and enhanced ROS production, but only the Tyr to Cys mutation self-inactivated cytochrome bc1. In the latter case, we tentatively propose that formation of an intersubunit disulfide cross-link, probably via ROS-induced cysteine redox chemistry (42), destabilizes the iron-sulfur protein [2Fe-2S] cluster by eliminating its own stabilizing intramolecular disulfide bridge (Fig. 8, top panel). The role of Tyr302 of cytochrome b in correctly positioning the iron-sulfur protein [2Fe-2S] cluster at the Qo site to confer optimal catalytic activity has been discussed in earlier studies for bacterial (16, 17) and yeast (18, 19) cytochrome bc1. However, in these studies, oxygen sensitivity of the enzyme or oxidative disintegration of its iron-sulfur protein [2Fe-2S] cluster has not been described. Although no Y302C mutant was examined in R. sphaeroides (17), it was reported that the homologous yeast Y279C mutant produced superoxide (18), but oxidative disruption of its iron-sulfur protein [2Fe-2S] cluster was not described (18, 19). It is noteworthy that R. capsulatus native cytochrome b has no Cys residue, whereas the yeast homologue has several, and one of them (Cys342) is located near Tyr279 of cytochrome b (supplemental Fig. S2, bottom panel). The distance that separates Tyr279 and Cys342 is large (∼10 Å) in the yeast native cytochrome bc1 structure. However, neither the corresponding distance in the Y279C mutant nor the occurrence of an intracytochrome b disulfide bond not affecting the [2Fe-2S] cluster stability is currently known.

Interestingly, the bovine and chicken native cytochrome b subunits also contain several Cys residues, but they lack a homologue of Cys342 or any other Cys residue near its Tyr278 (Fig. 8, bottom panel). Thus, as in R. capsulatus, in bovine, chicken, and possibly human cytochrome bc1, the iron-sulfur protein Cys residues remain as the likely candidates to yield an intersubunit disulfide bond upon Cys substitution of Tyr278 in cytochrome b.

How a Tyr at a specific position of cytochrome bc1 interferes with ROS production is not obvious. We note that replacing Tyr with other amino acids (including Phe) eliminates a key hydroxyl group at position 302 of cytochrome b and enhances antimycin A-independent ROS production by the Qo site. The high resolution structures of cytochrome bc1 indicate that Tyr302 is mobile, and its position depends on that of the iron-sulfur protein at the Qo site. Moreover, this residue is solvated, with its hydroxyl group within H-bonding distances from a cluster of H2O molecules (38). It is possible that elimination of this H2O cluster in Y302X mutants enhances unproductive encounters between O2 and dangerous one-electron Qo site intermediates. Mutants losing the hydroxyl group would exhibit decreased cytochrome bc1 activity, presumably because of incorrect positioning of the iron-sulfur protein [2Fe-2S] cluster at the Qo site and also produce more ROS to endanger host cell viability. Indeed, permanent ROS production induces lethal cellular damages but hypoxia-induced transient ROS generation by cytochrome bc1 could act as a signal for oxidative stress conditions (4, 7). Reversible chemical modifications of residues such as this Tyr might be of physiological significance.

Besides the bacterial Y302C, homologous human Y278C and malarial Y268C cytochrome bc1 mutants also exhibit decreased Qo site activities (12, 13). However, whether they produce ROS remains unknown. Extrapolation of the information gained using the bacterial cytochrome bc1 to the evolutionarily conserved organelle homologues suggests that human mitochondrial cytochrome b Tyr278 mutants might produce ROS, and cytochrome bc1 variants with Tyr to Cys mutations might self-inactivate via oxidative disruption of their [2Fe-2S] clusters. Although this inference awaits experimental validation, it also suggests that resistance to the antimalarial drug atovaquone by the parasite might be acquired at the expense of increased O2 sensitivity and concomitant decrease of energetic efficiency of the Qo site (16). Recent findings indicate that malarial cytochrome bc1 might have different selective pressure than most other systems (46) to allow the survival of O2-compromised atovaquone resistant parasites in microaerobic human host environment. Regarding the human cytochrome bc1, all Y278X but C substitutions would have decreased activity and kill host cells by continuous ROS production. Only the self-inactivating Y278C allele of cytochrome bc1 would cease ROS production via oxidative disruption of the [2Fe-2S] cluster and allow somewhat better host cell viability. However, even in this case, the hampered catalytic efficiency of the Y278C variant, combined with progressive loss of heteroplasmic state and differing energy threshold requirements of various tissues, would cause progressively increasing mitochondrial dysfunctions. These include exercise intolerance (15), ischemic cardiomyopathy (47), reperfusion injury (48), and multi-system disorder (12). Clearly, reversible modification of a critical hydroxyl group of cytochrome bc1 might be beneficial as a ROS signal initiator, but its permanent loss by mutation would steer mitochondria to a disastrous destiny via continuous oxidative damage and cell death.

Supplementary Material

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2.

- QH2

- reduced quinone (hydroquinone)

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- MOPS

- 4-morpholinepropanesulfonic acid

- IAM

- idoacetamide

- DBH2

- decylbenzo-hydroquinone

- Stg

- stigmatellin

- SOD

- superoxide dismutase.

REFERENCES

- 1. Crofts A. R. (2004) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 66, 689–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Weinberg F., Chandel N. S. (2009) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1177, 66–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ow Y. P., Green D. R., Hao Z., Mak T. W. (2008) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 532–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Poyton R. O., Ball K. A., Castello P. R. (2009) Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 20, 332–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Turrens J. F. (2003) J. Physiol. 552, 335–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Klimova T., Chandel N. S. (2008) Cell Death Differ. 15, 660–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Guzy R. D., Hoyos B., Robin E., Chen H., Liu L., Mansfield K. D., Simon M. C., Hammerling U., Schumacker P. T. (2005) Cell Metab. 1, 401–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Taylor R. W., Turnbull D. M. (2005) Nat. Rev. Genet. 6, 389–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lin M. T., Beal M. F. (2006) Nature 443, 787–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tatsuta T., Langer T. (2008) EMBO J. 27, 306–314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Balaban R. S., Nemoto S., Finkel T. (2005) Cell 120, 483–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wibrand F., Ravn K., Schwartz M., Rosenberg T., Horn N., Vissing J. (2001) Ann. Neurol. 50, 540–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Srivastava I. K., Morrisey J. M., Darrouzet E., Daldal F., Vaidya A. B. (1999) Mol. Microbiol. 33, 704–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Korsinczky M., Chen N., Kotecka B., Saul A., Rieckmann K., Cheng Q. (2000) Antimicrob. Agents. Chemother. 44, 2100–2108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Andreu A. L., Hanna M. G., Reichmann H., Bruno C., Penn A. S., Tanji K., Pallotti F., Iwata S., Bonilla E., Lach B., Morgan-Hughes J., DiMauro S. (1999) N. Engl. J. Med. 341, 1037–1044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mather M. W., Darrouzet E., Valkova-Valchanova M., Cooley J. W., McIntosh M. T., Daldal F., Vaidya A. B. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 27458–27465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Crofts A. R., Guergova-Kuras M., Kuras R., Ugulava N., Li J., Hong S. (2000) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1459, 456–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wenz T., Covian R., Hellwig P., Macmillan F., Meunier B., Trumpower B. L., Hunte C. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 3977–3988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fisher N., Castleden C. K., Bourges I., Brasseur G., Dujardin G., Meunier B. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 12951–12958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Darrouzet E., Moser C. C., Dutton P. L., Daldal F. (2001) Trends Biochem. Sci. 26, 445–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Berry E. A., Guergova-Kuras M., Huang L. S., Crofts A. R. (2000) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69, 1005–1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Osyczka A., Moser C. C., Daldal F., Dutton P. L. (2004) Nature 427, 607–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Esser L., Gong X., Yang S., Yu L., Yu C. A., Xia D. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 13045–13050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Snyder C. H., Gutierrez-Cirlos E. B., Trumpower B. L. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 13535–13541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Osyczka A., Moser C. C., Dutton P. L. (2005) Trends Biochem. Sci. 30, 176–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cape J. L., Bowman M. K., Kramer D. M. (2006) Trends. Plant. Sci. 11, 46–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Atta-Asafo-Adjei E., Daldal F. (1991) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 492–496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Valkova-Valchanova M. B., Saribas A. S., Gibney B. R., Dutton P. L., Daldal F. (1998) Biochemistry 37, 16242–16251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lee D. W., Ozturk Y., Osyczka A., Cooley J. W., Daldal F. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 13973–13982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Darrouzet E., Valkova-Valchanova M., Moser C. C., Dutton P. L., Daldal F. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 4567–4572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Darrouzet E., Valkova-Valchanova M., Daldal F. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 3464–3470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Muller F., Crofts A. R., Kramer D. M. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 7866–7874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Onder O., Yoon H., Naumann B., Hippler M., Dancis A., Daldal F. (2006) Mol. Cell Proteomics 5, 1426–1436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Onder O., Turkarslan S., Sun D., Daldal F. (2008) Mol. Cell Proteomics 7, 875–890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Onder O., Aygun-Sunar S., Selamoglu N., Daldal F. (2010) Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 675, 179–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhang Z., Huang L., Shulmeister V. M., Chi Y. I., Kim K. K., Hung L. W., Crofts A. R., Berry E. A., Kim S. H. (1998) Nature 392, 677–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Berry E. A., Huang L. S., Saechao L. K., Pon N. G., Valkova-Valchanova M., Daldal F. (2004) Photosynth. Res. 81, 251–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Solmaz S. R., Hunte C. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 17542–17549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kolling D. J., Brunzelle J. S., Lhee S., Crofts A. R., Nair S. K. (2007) Structure 15, 29–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cape J. L., Bowman M. K., Kramer D. M. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 7887–7892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Davidson E., Daldal F. (1987) J. Mol. Biol. 195, 13–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Poole L. B., Nelson K. J. (2008) Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 12, 18–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Crofts A. R., Hong S., Ugulava N., Barquera B., Gennis R., Guergova-Kuras M., Berry E. A. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 10021–10026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Drose S., Brandt U. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 21649–21654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hoffman D. L., Brookes P. S. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 16236–16245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Painter H. J., Morrisey J. M., Mather M. W., Vaidya A. B. (2007) Nature 446, 88–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Marin-Garcia J., Hu Y., Ananthakrishnan R., Pierpont M. E., Pierpont G. L., Goldenthal M. J. (1996) Biochem. Mol. Biol. Int. 40, 487–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lesnefsky E. J., Hoppel C. L. (2003) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 420, 287–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.