Abstract

The spindle pole body of the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae has served as a model system for understanding microtubule organizing centers, yet very little is known about the molecular structure of its components. We report here the structure of the C-terminal domain of the core component Cnm67 at 2.3 Å resolution. The structure determination was aided by a novel approach to crystallization of proteins containing coiled-coils that utilizes globular domains to stabilize the coiled-coils. This enhances their solubility in Escherichia coli and improves their crystallization. The Cnm67 C-terminal domain (residues Asn-429—Lys-581) exhibits a previously unseen dimeric, interdigitated, all α-helical fold. In vivo studies demonstrate that this domain alone is able to localize to the spindle pole body. In addition, the structure reveals a large functionally indispensable positively charged surface patch that is implicated in spindle pole body localization. Finally, the C-terminal eight residues are disordered but are critical for protein folding and structural stability.

Keywords: Crystallography, Mitotic Spindle, Protein Folding, Protein Structure, Spindle Pole Body, Coiled-coil

Introduction

The spindle pole body (SPB)2 of the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae serves as a simple model system for understanding microtubule organizing centers, which play essential roles in a wide variety of cellular functions including chromosome segregation during mitosis and meiosis, cytokinesis, fertilization, cell motility, and intracellular trafficking (1, 2). These massive multiprotein organelles vary widely across eukaryotes in organization, but they share conserved regulatory and structural components as well as the same function of microtubule nucleation.

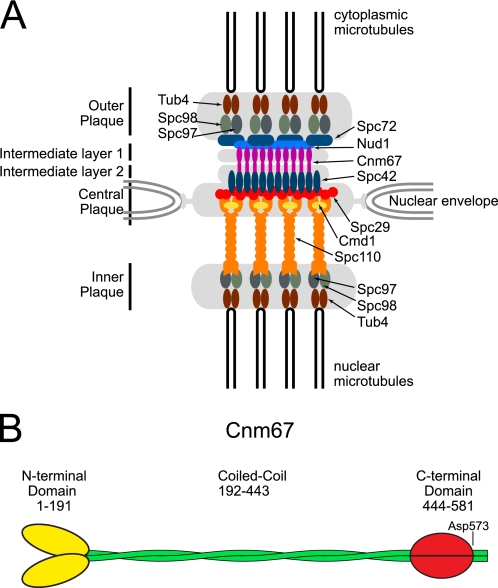

In S. cerevisiae, the SPB is the sole site for microtubule nucleation and is functionally analogous to the centrosome in animals cells. Unlike the centrosome, the SPB is located in the nuclear envelope, which in yeast remains intact throughout the cell cycle. Microtubules extend from the SPB into both the cytoplasm and the nucleus. Considerable effort has been devoted to understanding the organization, composition, and assembly of the SPB, and yet very little is known about the high resolution structural features of this assembly. Cryoelectron microscopy and electron tomography have shown that the SPB consists of multiple interconnected layers that include the nuclear inner plaque, the cytoplasmic outer plaque, and the central plaque that is embedded in the nuclear envelope (Fig. 1A). The central plaque is associated on one side with an electron-dense region in the nuclear envelope known as the half-bridge. This electron dense region is the location where the new SPB is assembled (3). In addition to the major layers, two less distinct layers, known as the first and second intermediate layers (IL1 and IL2), have been identified between the central and outer plaques. Approximately 18 proteins are included in the core complex (4). The topological arrangement of the core protein components that form the scaffold within the SPB has been determined using immunofluorescence microscopy, electron microscopy, electron tomography, and FRET analysis (3, 5–7). The central plaque and IL2 are closely associated and contain five proteins; Spc110, Cmd1, Spc29, Spc42, and Cnm67. Spc29 and Cmd1 are located in the central plaque. The C terminus of Spc110 localizes to the central plaque and binds to Cmd1 (calmodulin). Spc29 is believed to function as a bridge between Spc110 and Spc42 (8). Spc42 originates in the central plaque, where it interacts with Spc29 and extends into the IL2 layer where its C terminus interacts with the C terminus of Cnm67. The N terminus of Cnm67 interacts with the outer plaque protein Nud1 (8).

FIGURE 1.

Consensus model of SPB core and the domain structure of Cnm67. A, the schematic arrangement of the major proteins in the SPB that has been determined by a combination of immunofluorescence microscopy, electron microscopy, electron tomography, and FRET analysis. Of these proteins, the three-dimensional structures of only Tub4 (tubulin), calmodulin, and a short section of coiled-coil within Spc42 are known. This figure was redrawn from Jaspersen and Winey (4). B, Cnm67 is predicted to consist of N- and C-terminal globular domains connected by a long dimeric coiled-coil. The domain boundary for the N-terminal domain was derived from the coiled-coil prediction programs Coils and Paircoil2 (42–45). The end of the globular domain, Asp-573, as evident from the subsequent structural determination, is indicated.

The only three-dimensional structures known for the SPB components are calmodulin (Cmd1), centrin bound to an α-helical fragment of Sfi1, and γ-tubulin (Tub4) (9, 10). The structure of a SPB-associated microtubule binding domain of XMAP215, a vertebrate equivalent of Stu2 in S. cerevisiae, is also known (11). In addition, the structure of a section of the coiled-coil of Spc42 has been determined (12). Overall knowledge of the structure of the SPB and its components has been hindered by difficulties in expressing the proteins in soluble form suitable for structural studies. In part this is due to a preponderance of proteins that contain long sections of coiled-coil, which results in highly asymmetric proteins that are not readily amenable to crystallographic analysis. Clearly, structural studies would benefit from the construction and expression of individual domains.

Sequence analysis predicts that more than half of the core proteins in the SPB contains sections of coiled-coil that connect globular domains. In the case of Spc110, Spc42, Cnm67, and Spc72, there is good evidence that these extended tertiary structural motifs serve to connect the layers that constitute the SPB (7, 12–14). The presence of coiled-coils implies that many of the proteins in the SPB are constitutive dimers, and it is expected that the dimeric structure will be important for productive protein-protein interactions through cooperativity between globular domains within the SPB. In addition, the folding of many of the globular domains themselves will be profoundly influenced by the preceding or succeeding coiled-coils, because of the cooperative nature of protein folding. Thus, any effort to express functional domains of the SPB proteins should have the capacity to maintain the dimeric (or trimeric) state imposed by the presence of coiled-coils.

The simplest solution to expressing a dimeric globular domain associated with a region of coiled-coil would be to include a section of the endogenous dimerizing coiled-coil, possibly with the addition of a leucine zipper to stabilize the assembly. Leucine zippers, such as that found in the transcription factor GCN4, have been used successfully to determine the structures of the fragments of coiled-coils in myosin (15), tropomyosin (16, 17), and vimentin (18), in which the zipper has been added to either the N or the C termini of the protein of interest. However, the disadvantage of inclusion of an extended section of coiled-coil is that the proteins will necessarily be highly asymmetric and, hence, might be difficult to crystallize. For example, a GCN4 leucine zipper plus an additional heptad from the coiled-coil of the target protein would create a coiled-coil that was at least 55 Å long with a diameter of ∼20 Å. In contrast, a globular domain, such as the C-terminal region of Cnm67, which consists of 135 amino acid residues, can be expected to have a diameter of 30–40 Å.

An alternative approach would be to replace the extended coiled-coil with a globular motif that would maintain the same symmetry. One such motif is that found in the scaffolding protein Gp7 from bacteriophage ϕ29 (19, 20), which consists of a four-helix bundle that caps a coiled-coil. The helical bundle is ∼28 Å in diameter and less than 30 Å in length. We report here the structural and functional characterization of the C-terminal globular domain of Cnm67 fused to the helical bundle of Gp7 through a short section of coiled-coil.

Cnm67 is an integral component of the SPB. Cells in which this protein has been deleted do not exhibit an outer plaque, experience severe defects in nuclear migration, and grow extremely slowly (21). The protein is predicted to consist of an N-terminal domain of ∼190 amino acid residues connected to a C-terminal domain of ∼135 amino acid residues by a discontinuous coiled-coil ∼256 residues in length (Fig. 1B). The C-terminal region of Cnm67 interacts with Spc42, whereas the N-terminal region interacts with Nud1 in the outer plaque (8). In this way, Cnm67 functions as a spacer between the outer plaque and central plaque (14).

The structural studies described here reveal that the C-terminal globular domain of Cnm67 contains a new compact protein fold in which the helices from one polypeptide interweaves with those of the 2-fold related chain as they emanate from the coiled-coil region of the molecule. In vivo studies show that the globular domain alone is sufficient for localization of Cnm67 at the SPB and that exposed hydrophobic residues at the C terminus of the protein determine its structural stability. In addition, this study reveals that a positively charged patch on the surface of Cnm67 is important for SPB localization. This report also provides an example of a new approach to studying coiled-coil-containing proteins. Incorporation of a compact globular domain to stabilize coiled-coil domains is shown to be particularly beneficial in structural studies.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cloning and Expression Vectors

All oligonucleotides were purchased in desalted form (Integrated DNA Technologies) and were used without purification. PfuUltra or PfuUltra II Fusion DNA polymerases (Stratagene) were used in all PCR reactions according to manufacturer's recommendations. All QuikChange mutagenesis was done essentially as described in the manual for QuikChange kit (Stratagene) with the following modifications; PfuUltra II Fusion DNA polymerase was used, “QuikChange solution” was substituted with pure DMSO, only one mutagenic primer was included in the reaction, 30 amplification cycles were used, and extension was done at 65 °C for 1 min/kbp. QuikChange cloning is a restriction enzyme-free cloning technique in which PCR product that contains the gene of interest flanked by sequences that anneal to the target plasmid is used in place of oligonucleotide primers in a standard QuikChange reaction (22, 23). The conditions that differed from the published protocol are as follows; PfuUltra II Fusion DNA polymerase was used, 4% DMSO was typically included, 1 min annealing time was used, extension time used was 2 min/kb at 65 °C, and 50 ng of template plasmid and 100–150 ng of PCR product were used in a 25 μl reaction. All constructs generated throughout the studies were sequence-verified over the entire ORF insert and at least 50 bp upstream and downstream of the ORF.

Expression in E. coli employed pKLD115, a pET31b vector (Novagen) modified to include an N-terminal His6 tag followed by an rTEV recognition site (24). Sequences coding for amino acid residues Pro-2—Leu-53 of the scaffolding protein Gp7 from bacteriophage ϕ29 and Cnm67 residues Lys-415—Lys-581 were amplified by PCR from an expression vector (obtained from Dr. Dwight Anderson, University of Minnesota) and S. cerevisiae genomic DNA, respectively, and cloned into an expression vector by conventional restriction cloning. From this, working constructs were made by the deletion of appropriate sequences using QuikChange mutagenesis. The final expressed Gp7-Cnm67C fusion contained residues Pro-2—His-50 of Gp7 followed by residues Asn-429—Lys-581 of Cnm67. The C-terminal globular domain of Cnm67 consisted of Cnm67 residues Asn-444—Lys-581. EB1 cDNA was obtained from Open Biosystems (IMAGE clone ID 6527006), and its fragment was cloned into Cnm67-containing vectors using QuikChange cloning.

Yeast expression vectors used in intracellular localization studies were based on pYES2 (Invitrogen). All constructs encoded an N-terminal full-length GFP fused to the appropriate fusion partner. In all cases the start codon of the expressed ORF was located immediately after the pYES2 sequence ATAGGGAATA, and the pYES2 sequence that followed the ORF TAA stop codon was AGATATCCAT. These vectors were made by a combination of PCR overlap extension (to make fusions of GFP with Cnm67 or Gp7-Cnm67C) and QuikChange cloning. Plasmids for yeast complementation studies were based on an integration vector, pRS304 (25). pRS304-KanMX-cnm67 containing full-length cnm67 was generated previously by inserting a fragment of yeast chromosome that contains cnm67 gene as well as the 317 bp upstream and 340 bp downstream of the ORF into pRS304-KanMX using the blunt SmaI site (26).

All constructs used in the experiments described in the paper are listed in supplemental Table S1. After tag removal, Gp7-Cnm67C expressed in E. coli contained non-native peptide GGSG preceding Pro-2 of Gp7. GFP fusion proteins expressed in yeasts contained the “GFPplus” GFP mutant (F64L, S65T, F99S, M153T, V163A) with a nucleotide sequence identical to that found in the pRU1701 plasmid (GenBankTM accession number AJ851277.1). GFP was fused to the native protein sequence (Cnm67 or Gp7 as appropriate) through a linker with a sequence GGTSENLYFQGGSG. All of the Cnm67-EB1 fusions contained the appropriate Cnm67 sequence fused through a single glycine spacer to the residues Val-200—Asp-257 of EB1.

Protein Expression, Purification, and Crystallization

The selenomethionine-labeled Gp7-Cnm67 fusion with an N-terminal rTEV-cleavable His6 tag was produced in E. coli BL21 CodonPlus cells (Stratagene) in M9 medium utilizing a metabolic inhibition protocol (27). Cells were grown at 37 °C until an A600 of ∼0.6 (as measured in a Beckman DU640B spectrophotometer) and cooled on ice, 1 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside was added, and the growth resumed overnight at 16 °C. Cells were collected by centrifugation, and the cell paste was frozen in liquid nitrogen. For purification, 5 g of cell pellet was added to 25 ml of ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mm NaH2PO4, 300 mm NaCl, and 20 mm imidazole, pH 8.0, at room temperature) containing 0.5 mg/ml lysozyme, 1 mm PMSF, and 1 tablet of EDTA-free protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science). Cells were lysed by sonication and centrifuged, and the cleared lysate was applied to a 6 ml Ni-NTA column (Qiagen). The column was washed with 50 ml of lysis buffer and eluted with a 64 ml imidazole gradient (0–500 mm) in the lysis buffer. The purest fractions were pooled (28 ml at ∼4.2 mg/ml protein) and dialyzed overnight against 1 liter of buffer A (20 mm Tris, 200 mm NaCl, 0.2 mm EDTA, 1 mm DTT, pH 8.3, as measured at 4 °C without a temperature probe). Next, 2 mg of rTEV (28) was added and incubated for 3 h at room temperature followed by overnight incubation at 4 °C. The cleaved protein was reloaded onto the same Ni-NTA column equilibrated with buffer A, and the column was washed with 20 ml of buffer A. The flow-through and wash fractions containing the purest Gp7-Cnm67 protein were pooled, dialyzed against 1 liter of buffer B (20 mm Tris, 100 mm NaCl, 0.5 mm tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine, pH 8.3 at 4 °C), concentrated using a Centriprep YM-10 (Millipore) to ∼2.5 ml, clarified by centrifugation, frozen as 30 μl drops into liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C.

All other Cnm67-containing proteins were expressed in native form, and the purification, where attempted, used identical or very similar conditions. For the experiments shown in Fig. 6 and supplemental Fig. S3, the rTEV cleavage and second chromatographic step were omitted, proteins were dialyzed into a buffer and then concentrated and frozen as described for an rTEV-cleaved preparation. In all cases the protein concentration was estimated from their absorbance at 280 nm using the theoretical extinction coefficient calculated by ProtParam (29).

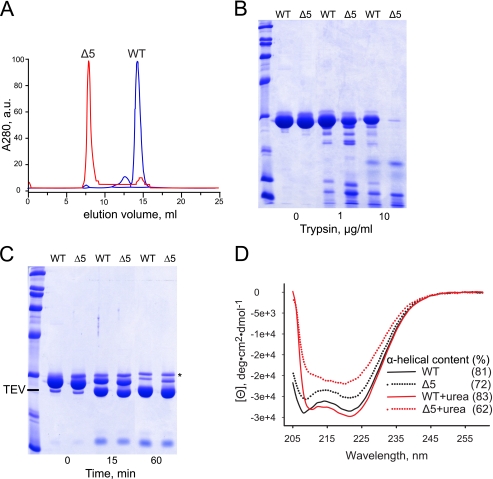

FIGURE 6.

Characterization of the Gp7-Cnm67CΔ5 mutant protein. A, size-exclusion chromatography. The purified His6-tagged wild-type Gp7-Cnm67C and the mutant Gp7-Cnm67CΔ5 were chromatographed on a 10/30 Superdex 200 column. Unlike the wild type, the mutant protein elutes in the void column volume. a.u., absorbance units. B, rates of proteolytic degradation. Purified His6-tagged wild-type Gp7-Cnm67C and mutant Gp7-Cnm67CΔ5 (∼2 mg/ml each) were incubated for 45 min at room temperature in the presence of the indicated concentrations of trypsin and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The mutant protein is significantly more susceptible to proteolysis. C, protease accessibility of the N terminus. The purified His6-tagged wild-type Gp7-Cnm67C and the Gp7-Cnm67CΔ5 deletion mutant protein (∼2 mg/ml each) were incubated with 0.1 mg/ml purified TEV and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The asterisk indicates a contaminant protein that co-purifies with Cnm67 during the first step of the purification. No significant difference in the rate of TEV digestion can be observed. The N-terminal His6 affinity tag precedes the Gp7 moiety, indicating the solvent exposure of Gp7 is approximately the same in both constructs and implying that the GP7 moiety is folded in both proteins. D, circular dichroism spectra of the His6-tagged purified wild-type Gp7-Cnm67C protein (solid lines) and the Gp7-Cnm67CΔ5 deletion mutant protein (dotted lines) without (black lines) and with (red lines) 2.0 m urea. Shown in parentheses are the percentage calculated α-helical content of the respective proteins. Note that the Δ5 mutant protein displays a lower α-helical content, indicating that it is partially unfolded. Under the conditions of the experiment, urea has little effect on the wild-type protein, whereas it causes an additional ∼10% drop in the α-helical content of the mutant protein. Taken together, the size-exclusion, proteolysis susceptibility, and secondary structure analysis unambiguously show that the mutant protein is aggregated and partially unfolded.

Crystals of selenomethionine-substituted Gp7-Cnm67C were grown by vapor diffusion at room temperature from a 1:1 mixture of protein at 10 mg/ml and 10–11% monomethyl polyethylene glycol 5000, 1.0 m tetramethylammonium chloride, and 100 mm CHES, pH 9.0. Crystals grew to dimensions of about 400 × 200 × 80 μm in approximately 2 weeks. The crystals were cryopreserved by a stepwise transfer into a solution containing 12% monomethyl polyethylene glycol 5000, 1.2 m tetramethylammonium chloride, 100 mm CHES, pH 9.0, and 10% ethylene glycol. They were then flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction quality crystals of native Gp7-Cnm67C protein were also grown using two alternative conditions. Low pH precipitant solution contained 16% monomethyl polyethylene glycol 5000, 50% ethylene glycol, 50 mm acetic acid, and 50 mm MES, pH 5.5. High salt precipitant contained 2.4 m ammonium phosphate, 100 mm HEPPS, pH 8.0.

Data Collection and Structure Determination

Data were collected at a wavelength of 0.97921 Å at the SBC Beamline 19-BM (Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne, IL) and processed with HKL2000 (30). The crystals of Gp7-Cnm67 fusion protein belonged to space group C2221, with unit cell dimensions of 58.6 × 198.6 × 53.2 Å. The solvent content of the crystals was 62% with one chain in the asymmetric unit cell (VM 3.3 Å3dalton−1). The structure was solved with Solve/Resolve (31–34) utilizing a selenomethionine SAD experiment. Molecular replacement with Gp7 fragment 2–50 (PDB ID 1NO4) using Phaser (35) found a solution that matched the experimental solution from SAD phasing. The initial model was built by ARP/wARP (36) starting from the existing structure of Gp7 (residues 2–50 from 1NO4) and using the experimental phase restraints option. This was followed by iterative cycles of manual model building in Coot (37) and refinement directly against SAD data in Refmac 5.5 with restrained and TLS refinement (38). Data processing and refinement statistics are presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Crystallographic and refinement statistics

| Data processing | |

| Space group | C2221 |

| Cell dimensions:a, b, c (Å) | 58.6, 198.6, 53.2 |

| Resolution (Å) | 30.0-2.3 (2.38-2.30)a |

| Completeness (%) | 100 (100) |

| Redundancy | 10.7 (6.6) |

| Unique reflections | 14536 |

| Rmerge (%) | 10.1 (38.9) |

| Average I/σ | 16.2 (5.0) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 20.0-2.3 (2.36-2.30) |

| Rwork (%) | 23.8 (28.8) |

| Rfree (%) | 27.8 (35.0) |

| Protein atoms | 1590 |

| Water molecules | 18 |

| Wilson B value (Å2) | 73.7 |

| Average B factor (Å2) | 80.2 |

| Protein | 80.5 |

| Water molecules | 56.5 |

| Root mean square deviation | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.007 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.942 |

| Ramachandran (%) | |

| Favored region | 95.8 |

| Allowed region | 4.2 |

| Outlier region | 0.0 |

a The values in parentheses correspond to the statistics for the highest resolution shell.

Miscellaneous Biochemical Methods

Size-exclusion chromatography was performed on a 10/30 Superdex 200 column. In all cases, the running buffer was 20 mm Tris, 150 mm NaCl, 3 mm NaN3, 0.5 mm tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine at pH 8.0.

Far ultraviolet circular dichroism spectra were recorded using an Aviv Model 202SF CD Spectrophotometer at room temperature. Proteins were analyzed at 0.12 mg/ml in 50 mm sodium phosphate buffer at pH 7.5 with or without 2 m urea. The proportion of the α-helical content was calculated from the molar ellipticity at 222 nm according to Morrow et al. (39).

Proteolytic experiments were performed with the Cnm67 proteins at 2 mg/ml in 20 mm HEPES, 100 mm NaCl, 0.5 mm tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine at pH 7.5. The reaction products were analyzed on a 12% SDS-PAGE gel.

The solubility of the GFP-Cnm67 fusion proteins was tested as follows. Proteins were expressed as suggested in the manual for pYES2 published by Invitrogen, with the exception that strain W303 was used for expression. One gram of washed cells was resuspended in 5 ml of buffer (20 mm HEPES, 100 mm NaCl, 1 mm tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine plus protease inhibitors from “Complete” tablets, Roche Applied Science), lysed by bead beating, and centrifuged for 5 min at 12,000 × g to remove cell debris. 150 μl of the resulting supernatants were centrifuged for 15 min at 80,000 rpm in Beckman TLA 100.1 rotor.

Yeast Localization and Complementation Studies

The general yeast techniques were as described in Guthrie and Fink (40). Strains were derived from a W303 background. The localization experiments were performed by transforming yeasts with pYES2-derived plasmids containing the various GFP-Cnm67 fusion genes behind the GAL1 promoter and the URA3 gene (for selection on media lacking uracil). The cells were grown in a glucose-containing medium (repressing) lacking uracil to log phase (A600 = 0.4), washed, and then grown for several hours or overnight in a raffinose-containing medium lacking uracil. Cells were treated with 5 μg/ml Hoechst 33342 for 10 min to stain the DNA, washed, and spotted on microscope slides. Images were acquired on a Leica DMRXA/RF4/V automated microscope (Leica Microsystems, Bannockburn, IL) with a Photometrics COOL SNAP HQ2 digital camera (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ) and analyzed using Metamorph imaging software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). For complementation studies, wild-type or mutant CNM67 alleles on a plasmid containing a trp1 gene (for selection on media lacking tryptophan) were integrated into a heterozygous null CNM67 yeast strain (strain number MW3833). Two or more transformed diploids for each were sporulated, and tetrads were dissected. Ten complete tetrads were analyzed for a 2:2 segregation of tryptophan/G418 growth, and 2 complete tetrads for each transformant were streaked for growth on rich media plates at 25 °C and 37 °C.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

“Stopper Domain” Fusions Are Beneficial in Crystallographic Studies of Coiled-coil Proteins

To facilitate expression and crystallization of the Cnm67 C-terminal fragment, this study developed a new approach to studying coiled-coil proteins. It was hypothesized that substitution of a globular domain in place of the coiled-coil would result in a fusion protein that would be more amenable to structural and functional analysis. We call these constructs coiled-coil stopper domain fusions. This approach has been used successfully to determine the structure of the tropomyosin overlap complex (41). In the current investigation, the C-terminal region of Cnm67 was fused to the helical bundle of bacteriophage ϕ29 scaffolding protein Gp7 (20) to create a protein that was highly soluble when expressed in E. coli and crystallized exceedingly readily. This favorable solution behavior is in contrast to attempts to express the C-terminal region of Cnm67 alone or as a fusion protein with GCN4, in which cases the constructs were insoluble or apparently unstable (supplemental Table S2). Similarly, attempts to improve the solubility of the protein construct through the inclusion of a maltose binding protein solubility tag failed to yield soluble protein.

Careful consideration was given to the design of the junction between Gp7 and Cnm67 because the stability of a coiled-coil is determined not only by the interactions between amino residues in the helix interface but also by intrachain interactions between neighbors separated by three or four residues. The coiled-coil registration in Gp7 and Cnm67 was defined utilizing the programs Coils and Paircoil2 (42–45). These programs predicted that the heptad repeats in Cnm67 start at ∼Asn-192 and proceed through a series of coiled-coil segments that terminate at ∼Phe-442. The final fusion construct included residues Pro-2—His-50 of Gp7 and residues Asn-429—Lys-581 of Cnm67. Three heptad repeats were retained between the helix bundle of Gp7 and the start of the globular domain for Cnm67. The three heptads include one from Gp7 and two from Cnm67. To preserve stabilizing interactions, His-50 was retained as the last residue in Gp7 because it forms a hydrogen bond to Ser-49′ on the opposite chain. Asn-429 was chosen as the first residue from Cnm67 because the structurally equivalent residue in Gp7 (Glu-51) is surface-exposed and does not interact with any other residue so that the substitution was viewed as neutral. The resulting fusion protein was predicted to contain an excellent coiled-coil. The strategy utilized for designing the fusion protein is illustrated in greater detail in the supplemental Fig. S1.

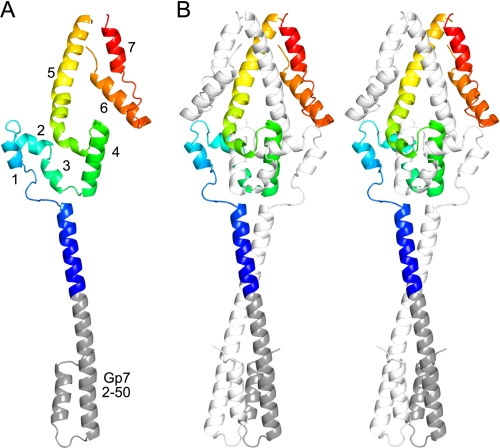

Crystallization and Structure Overview

Gp7-Cnm67C was highly overexpressed in E. coli at 16 °C, and the bulk of the protein was soluble. The protein was readily purified and crystallized under a wide range of conditions (∼50% of the conditions in the initial screen yielded crystals). The structure was determined to 2.3 Å resolution by a combination of SAD phasing and molecular replacement with Gp7. Crystallographic statistics are presented in Table 1, and a representative section of stereo omit map electron density is shown in supplemental Fig. S2. A ribbon representation of the structure is shown in Fig. 2. The structure is well defined from Pro-2—His-50 for Gp7 and Asn-429-Asp-573 for Cnm67. There is a small break in the electron density between Tyr-535 and Glu-537. Furthermore, the electron density for the C-terminal residues of Cnm67 (residues His-574—Lys-581) is largely missing. Lys-581 is the C-terminal residue in Cnm67. There is persistent and partially connected electron density that extends away from the last α-helix, but it is too weak to model with any confidence. Still, on the basis of the weak density, it appears likely that the C terminus continues as an α-helix beyond His-574. Thus, the C-terminal globular domain of Cnm67 is a constitutive dimer built from residues Asn-444—Asp-573.

FIGURE 2.

Structure of the Gp7-Cnm67 fusion protein. A, one subunit is shown to reveal the path of a single polypeptide chain, where the individual α-helixes are numbered. The residues of Gp7 are depicted in gray, whereas the residues of Cnm67 are colored in a rainbow scheme. B, a stereoview of the physiological homodimer is shown. For clarity, one polypeptide chain is colored as in A, whereas the other is depicted in white. Figs. 2, 5, and 7 were prepared with Pymol (50).

The structure of the Gp7 helical bundle is essentially identical to that determined previously and runs smoothly into the coiled-coil of Cnm67. The root mean square difference between the α-carbon atoms in the helical bundle in Gp7 (PDB accession number 1NO4 (20)) and the equivalent residues in the fusion protein with Cnm67 is 0.27 Å. An overlay between the helix bundle and coiled-coils is shown in supplemental Fig. S1.

The C-terminal domain of Cnm67 is dominated by seven α-helices of varying length connected by short non-helical segments. These α-helices form a complex helical bundle that is intertwined with the 2-fold related polypeptide chain. The first three α-helices loop away from the coiled-coil domain and lie on the surface of the globular domain, and thereafter, the polypeptide chain returns close to where it left the coiled-coil but in the position of the adjacent chain. The fourth α-helix lies in the core of the domain and continues the path of the coiled-coil, so that the first three helices can be viewed as an insertion into a coiled-coil. The fifth α-helix is angled across the 2-fold axis of the domain. The final two helices lie on the outside of the domain and pack against the 2-fold-related fifth helix. As a whole, the fifth, sixth, and seventh helices of both chains form a six-helix bundle. The fold terminates close to the 2-fold axis. According to the SSM server, there are no similar folds in the Protein Data Bank at the present time (46). A total 4350 Å2 of accessible surface area is buried by the dimer interface of the globular domain, which represents ∼40% of the total surface area available to these polypeptide chains. This buried surface area is unusually large for a homodimer that consists of only 131 amino acid residues per subunit (Asn-444–His-574).

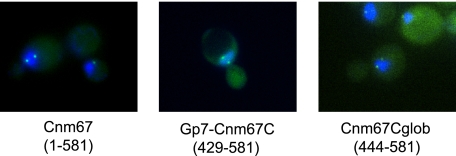

Globular Domain Alone Is Sufficient for SPB Localization

The addition of Gp7 to the C-terminal domain of Cnm67 greatly facilitated protein expression and a subsequent structural determination. To test whether this fusion protein retains a functional SPB binding motif despite the presence of the non-physiological Gp7, we investigated the intracellular localization of a GFP-Gp7-Cnm67C fusion protein. As shown in Fig. 3, the expressed GFP-Gp7-Cnm67C localizes to the two SPBs present in a budded yeast cell, demonstrating that the x-ray structure reported here contains a physiologically relevant domain of Cnm67.

FIGURE 3.

SPB localization of Cnm67 proteins. Indicated GFP fusions proteins were overexpressed in yeasts and assayed for their ability to label the SPB as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Hoechst-stained nuclear DNA is seen in blue, bright green dots represent the two SPBs present in budded yeast cells, and the green background fluorescence represents the GFP fusion protein distributed throughout the cytoplasm. It is evident that both the Gp7 fusion and the globular C-terminal domain alone are targeted to the SPB.

Intracellular localization of additional GFP fusion proteins was assessed to narrow the structural determinants of Cnm67 that target it to the SPB. Previous studies demonstrated that the C-terminal residues Thr-449–Lys-581 are necessary, but not sufficient, for localization of Cnm67 at the SPB (14). However, as shown in Fig. 3, a GFP fusion with only a slightly larger fragment, starting with Asn-444, does localize to the SPB. The structure of Gp7-Cnm67C suggests a possible explanation. It is likely that omission of residues Leu-445—Asn-448 is destabilizing because it results in a loss of several important contacts observed in the dimer. Most importantly, the hydrophobic side chain of Leu-483 is normally shielded by Leu-445′ of the opposing chain and would become exposed to the solvent when Leu-445—Asn-448 is removed. In the Gp7-Cnm67 fusion Leu-483 and Leu-483′ pack together with Leu-445 from both subunits at the base of the domain and appear to provide an important contribution to the hydrophobic core. There are also numerous hydrogen bonds that will be lost on removal of Leu-445—Asn-448, but these are expected to be thermodynamically neutral because of the potential for hydrogen bonding to water. Regardless of the exact explanation, it can be concluded that the coiled-coil region is not absolutely required for SPB localization and that the C-terminal globular domain is the major determinant that targets Cnm67 to the SPB.

Positively Charged Surface Patch and Its Significance

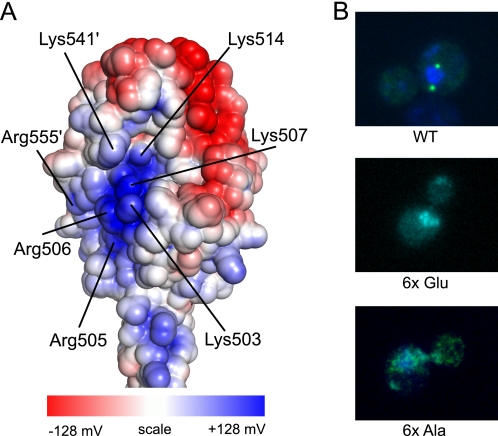

The structure of the Cnm67C exhibits a prominent positively charged patch on the exposed face of the globular C-terminal domain. It consists mostly of residues Lys-503, Arg-505, Arg-506, Lys-507, and Lys-514 of one polypeptide chain and Lys-541′ and Arg-555′ of another (Fig. 4A). To test the functional importance of the basic patch, mutant proteins were created, and their ability to localize to the SPB was tested. Six charged residues that contribute to the basic patch were mutated either to glutamate or alanine. Fig. 4B demonstrates that both charge reversal and charge removal completely eliminate SPB localization of the GFP-Gp7-Cnm67C mutant proteins. To control for the effects on protein folding and stability, the same Gp7-Cnm67 mutants were expressed in E. coli, purified, and subjected to size-exclusion chromatography. Both proteins are mostly soluble when expressed in E. coli (data not shown) and exhibit very similar retention times to that of the wild-type protein (supplemental Fig. S3). Evidence that the GFP-Gp7-Cnm67C wild-type protein is soluble in vivo is shown in supplemental Fig. S4. This confirms that mutation of six residues does not have a major effect on protein stability or on their aggregation state in solution. A potential explanation for the lack of localization is that the positively charged patch plays an important role in the known interaction between Cnm67 and the heavily phosphorylated C terminus of Spc42 in the SPB (47).3 The basic patch on the surface of the Cnm67 C-terminal domain thus appears to be a functionally indispensable structural feature of this protein.

FIGURE 4.

Basic patch on the surface of Cnm67 is functionally important. A, distribution of the electrostatic potential on the Cnm67 C-terminal domain. Shown is the calculated electrostatic potential on the solvent-accessible surface. The colors range from −128 to +128 mV. The residues that contribute most heavily to the prominent positively charged patch are labeled. The electrostatic potential was calculated with the program APBS plugin for Pymol (51). B, basic patch mutants fail to localize to SPB. Six basic residues (Lys-503, Arg-505, Arg-506, Lys-507, Lys-541, Arg-555) in GFP-Gp7-Cnm67C were mutated either to glutamate (middle) or alanine (bottom), and the resulting mutants along with the wild-type control (top) were assayed for SPB localization.

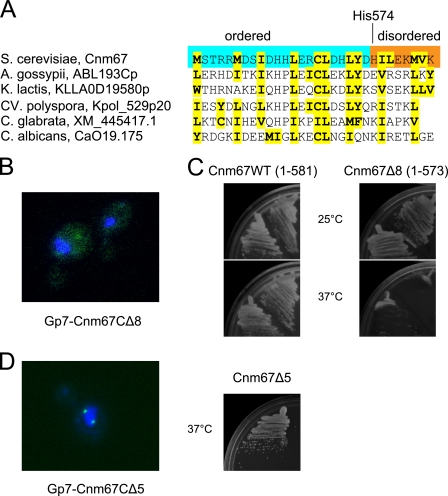

C-terminal Peptide Is Essential for Function

As noted earlier, the electron density for the C-terminal eight residues of Cnm67 (574-HILEKMVK-581) is largely missing, which indicates a higher degree of flexibility for this segment of the protein. Interestingly, this peptide contains four hydrophobic residues, which is very unusual for a disordered region. Yet, a BLAST search reveals this C-terminal feature is as well conserved across fungi as other preceding sections of the sequence (Fig. 5A). Because evolutionary conservation often implies functional or structural importance, the role of this unusual feature was investigated further. Fig. 5B illustrates that the mutant lacking the last eight residues (GFP-Gp7-Cnm67CΔ8) fails to localize to the SPB entirely. In addition, although wild-type Cnm67 rescues the slow growth phenotype of Cnm67 null at both 25 and 37 °C in a complementation assay, transformants with the truncation mutant lacking the last eight amino acid residues exhibit a temperature-sensitive phenotype, not growing at elevated temperatures (Fig. 5C). Interestingly, truncation of only five C-terminal residues results in a protein that exhibits wild-type behavior in SPB localization and null allele complementation assays (Fig. 5D). From these results, it is clear that the C-terminal tip of the protein is important for the function of Cnm67.

FIGURE 5.

C-terminal peptide is functionally important. A, shown is conservation of the C termini of Cnm67. Also shown is an alignment between Cnm67 and its putative homologs from other yeasts. Hydrophobic amino acid residues are highlighted in yellow. The C-terminal residues of Cnm67 that are disordered in the crystal structure are highlighted in orange. B, deletion of the last eight residues abolishes SPB localization of Cnm67. The localization of GFP-Gp7-Cnm67CΔ8 in yeast was assayed identically and in parallel with the experiments shown in Fig. 3. C, a small C-terminal deletion of Cnm67 results in a ts phenotype. Duplicate complementation assays of the Cnm67 null allele by the full-length wild-type control and its C-terminal deletion mutant were performed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The figure shows that haploid cells carrying the Δ8 mutation do not grow at 37 °C. D, the Δ5 C-terminal truncation mutants are not functionally compromised. Shown are the results of the intracellular localization assay for GFP-Gp7-Cnm67CΔ5 protein (left) and the null allele complementation assay by Cnm67CΔ5 gene (right). Normal SPB localization and growth at 37 °C are evident.

C-terminal Residues Determine the Structural Integrity of Cnm67

The last eight residues of Cnm67 could be important for binding to its partner, Spc42, and/or for protein folding and stability, although normally interactions that are important for protein stability are well ordered in protein crystal structures. The second possibility can be tested by determining the structure of the protein by using a different crystal form in which the “missing” residues can be observed and also by solving the structure of the truncation mutant.

Gp7-Cnm67C crystallized in a wide variety of conditions. Thus, the structure of Gp7-Cnm67C was re-determined from two sets of crystals grown under radically different conditions (PEG/pH 5.5 and high salt/pH 6.5 versus PEG/pH 9.0, see “Experimental Procedures”). In both cases, however, the structures were isomorphous with that described earlier but exhibited an even higher degree of disorder that included not only the C-terminal extension but also the second half of helix 5 (Phe-525—Glu-537) and the entirety of helix 7 (Ile-560–Lys-581) (data not shown). Thus, these structures failed to provide insight into the structural role of the C terminus of Cnm67.

It was not possible to determine the structure of the truncated Gp7-Cnm67CΔ8 because the protein was completely insoluble when expressed in E. coli (supplemental Table S2). This observation suggests that the C-terminal extension is important for structural stability, at least when the proteins are expressed in E. coli. To examine whether the C-terminal extension is important for folding in a eukaryotic cell, a parallel set of expression tests were performed in yeast. The same constructs, Gp7-Cnm67C and Gp7-Cnm67CΔ8 mutant, were overexpressed as GFP fusions in yeasts and assayed for solubility. Although the total GFP expression was nearly identical between the two, ultracentrifugation of cell lysates revealed dramatic differences; nearly all of the GFP protein remained in the supernatant in the case of wild-type fusion, whereas all of the GFP partitioned into pellet fraction in the case of the truncated mutant fusion protein (supplemental Fig. S4A). Thus, removal of the last eight residues from the C-terminal globular domain of Cnm67 renders the protein insoluble.

To determine how many of the C-terminal residues are required for proper folding and stability, additional mutant proteins, Gp7-Cnm67CΔ7 and Gp7-Cnm67CΔ5, were expressed in E. coli. Of these, Gp7-Cnm67CΔ5 (lacking merely the amino acid residues EKMVK), expressed in a partially soluble form that could be purified with low yield on Ni-NTA, whereas the Gp7-Cnm67CΔ7 mutant protein was insoluble.

Characterization of the purified Gp7-Cnm67CΔ5 construct, however, demonstrated that it is an aggregated protein since it sediments quantitatively upon ultracentrifugation (not shown), elutes in the void volume in size exclusion chromatography (Fig. 6A), and is far more susceptible to proteolytic degradation than its wild-type counterpart (Fig. 6B). At the same time, the folding of the N-terminal Gp7 fragment is unaffected as judged from the accessibility of N-terminal cleavable tag to the rTEV protease (Fig. 6C). The dramatic differences in structure between the fully folded wild-type and aggregated mutant forms is also made clear by their CD spectra (Fig. 6D, black lines). Aggregates do retain a significant fraction of α-helical content, but it is less than that of the soluble protein. The partially folded nature of the aggregates is further emphasized under conditions of mild denaturation. As shown in Fig. 6D (red lines), the α-helical content of the Gp7-Cnm67CΔ5 drops upon the addition of urea, whereas the wild-type α-helical content is virtually unchanged by 2 m urea.

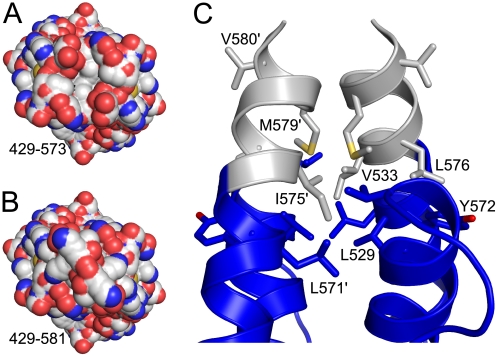

Collectively, the experimental evidence suggests that without its hydrophobic terminus, the seemingly very tight Cnm67 globular dimer (with >4000 Å2 buried!) unfolds and aggregates. The likeliest explanation for this is that the C-terminal residues function as a cover or clamp for a large hydrophobic patch that is evident at the tip of the globular domain adjacent to the dimer interface (Fig. 7A). Even though the C-terminal eight amino acid residues cannot be modeled as a single conformation, they are present and as such would prevent intermolecular contacts with other hydrophobic surfaces. Without this protection, unfavorable solvent exposure of the hydrophobic surface triggers aggregation and misfolding of the dimer. The profound influence of these disordered residues is surprising. As noted earlier, the weak electron density in the vicinity of Asp-573 (supplemental Fig. S5) suggests that the C-terminal peptide extends the length of the final α-helix in the structure (helix 7, Fig. 2). If this were the case, residues Ile-575, Leu-576, and Lys-578 would be expected to sequester the observed solvent-exposed hydrophobic patch (Fig. 7, B and C).

FIGURE 7.

Distribution of hydrophobic residues at the C terminus of Cnm67. A, end-on view of Cnm67 reveals a prominent exposed hydrophobic cleft in the absence of the eight C-terminal residues, which are missing in the experimental model. The carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen atoms are depicted in white, blue, and red, respectively. B, end-on view of Cnm67 after a putative C-terminal α-helical extension has been added to the model. These residues were built as an ideal α-helix into the weak electron density in the vicinity of Asp573. Supplemental Fig. S5 shows the difference electron density associated with this putative helical extension. The solvent-accessible surface representation of this model shows that this putative extension covers the exposed hydrophobic patch observed in the experimental model. C, shown is a schematic representation of the C terminus of Cnm67 including the putative helical extension. The experimental structure is depicted in blue, whereas the putative helical extension is depicted in white. The side chains for the hydrophobic residues associated with this part of the structure are shown in stick representation. This shows that the addition of a simple α-helix sequesters all of the exposed hydrophobic patch. Furthermore, the helical extension buries all the hydrophobic residues in the missing eight C-terminal residues, except for Val-580.

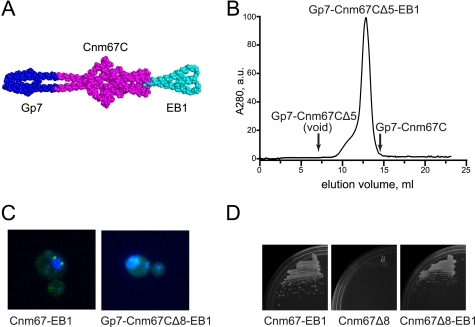

The C Terminus Is a Cover or Clamp, Not a Sequence-specific Binding Site

The preceding studies show that the C terminus of Cnm67 is essential for structural integrity, but they do not answer the question of whether these residues also contribute to protein-protein interactions within the SPB. To address this question, the last five residues of Cnm67 were replaced through a single glycine spacer with 58 residues from C terminus of the coiled-coil protein EB1 (48). The design of this construct followed the same logic as that outlined above for the design of the N-terminal stopper domain. The Gp7-Cnm67CΔ5-EB1 fusion protein included two coiled-coil heptads from EB1 followed by a four-helix bundle (Fig. 8A). The resulting protein was soluble when expressed in E. coli and, unlike the insoluble Gp7-Cnm67CΔ5, eluted at the expected volume and as a single peak when examined by size-exclusion chromatography. It did show a tendency for the slow accumulation of faster running, presumably aggregating, species (Fig. 8B).

FIGURE 8.

Essential C-terminal residues can be replaced with an unrelated coiled-coil. A, shown is a schematic model of the Gp7-Cnm67CΔ5-EB1 fusion protein. The main-chain atoms in the model are depicted in a sphere representation, where GP7, Cnm67, and EB1 are colored in blue, magenta and cyan, respectively. The structure of the Gp7-Cnm67CΔ5-EB1 fusion protein was not determined in this study and is shown only to illustrate the anticipated dimeric and coiled-coil nature of the protein. The structure of EB1 was taken from PDB accession number 1YIB (48). a.u., absorbance units. B, size-exclusion chromatography of the C-terminal-capped Gp7-Cnm67CΔ5-EB1 fusion protein. His6-tagged fusion protein was gel-filtered under the same conditions as in Fig. 4A. Unlike the unclamped mutant, the C-terminal EB1 fusion does not elute in the void column volume but elutes earlier than the wild-type Gp7-Cnm67. A small portion of the purified protein elutes earlier, resulting in a shoulder. The exact nature of this fraction is unknown. C, intracellular localization of the EB1 fusion proteins is shown. Indicated GFP fusions proteins were overexpressed in yeasts and assayed for their ability to label the SPB. The EB1 fusion with wild-type protein does not interfere with its labeling of the SPB (left), demonstrating that the C terminus of Cnm67 is not directly involved in the localization of Cnm67 to the SPB. The EB1 fusion with the deficient Δ8 truncation mutant fails to restore its targeting to the SPB (right). D, C-terminal EB1 fusions are functional in a complementation assay. Shown is growth of the cultures containing indicated recombinant alleles at 37 °C. The figure demonstrates that the EB1 C-terminal clamp is not detrimental for wild-type and rescues ts phenotype of the Δ8 mutant.

The stabilizing influence of the C-terminal EB1 fusion was also observed for the GFP fusions of Gp7-Cnm67CΔ5 and Gp7-Cnm67CΔ5-EB1 expressed in yeasts; whereas the majority of the truncation mutant sedimented upon ultracentrifugation, most of its EB1 counterpart remained in solution (supplemental Fig. S4B). These results indicate that the non-physiological EB1 polypeptide is able to at least partially compensate for the lack of the native sequence when protein solubility is assayed in vitro. To test whether the EB1 peptide alleviates an in vivo defect as well, we employed the Cnm67Δ8 construct, which was defective in both SPB localization and in complementation of a CNM67null mutation. Control experiments established that EB1, when fused to the native C terminus of Cnm67, does not interfere with the normal behavior of the protein in functional assays such as SPB localization (Fig. 8C) and complementation of the null Cnm67 allele (Fig. 8D). This observation provided a way to examine whether the C-terminal EB1 clamp is capable of alleviating the temperature sensitivity of the Cnm67CΔ8 mutant and its deficiency in SPB localization. Our results showed that whereas the C-terminal EB1 fusion is unable to facilitate localization of the GFP-Gp7-Cnm67CΔ8-EB1 fusion protein to the SPB (Fig. 8C), the EB1 fusion does improve function in the more sensitive complementation assay and rescues the temperature-sensitive phenotype of Cnm67Δ8 mutant (Fig. 8D).

The results on the role of Cnm67 C-terminal peptide can be summarized and explained in the following manner. 1) All Cnm67 C-terminal truncation mutants that have been tested are structurally and/or functionally compromised in comparison to the wild-type protein. 2) The Δ8 mutant is compromised most severely, whereas the Δ5 mutant suffers considerably less. The Δ5 mutant exists as an equilibrium between aggregated non-functional and non-aggregated functional forms, and this equilibrium is shifted toward aggregated forms in vitro. 3) The C-terminal EB1 fusion is able to partially substitute for the native C-terminal peptide both in vitro and in vivo, resulting in a shift of the equilibrium toward natively folded non-aggregated form. The extent of recovery depends on the number of missing native amino acid residues. Taken together, these results strongly suggest that the conserved Cnm67 C terminus is a cover or clamp that ensures the protein structural stability and that it is not essential for interactions that define SPB assembly and function. The fact that the SPB is able to accommodate a 50 Å-long bulky EB1 extension implies that the binding site for the C-terminal domain of Spc42 does not include the C-terminal tip of Cnm67, supporting the notion that the basic patch on the side of Cnm67 is a component of the Spc42 binding site (Fig. 4A).

Concluding Remarks

This study provides the first structural determination for an integral globular component unique to a microtubule organizing center. It reveals a new protein fold that can only exist as an intercalated dimer, which is unusual among structural motifs. The structure precisely defines the boundaries between the globular domain and the coiled coil of Cnm67 C terminus and narrows the determinants of its protein-protein interactions within the SPB, identifying a putative binding site for Spc42. The results uncover a surprising role for the last few C-terminal amino acid residues in the stability of the protein. This has important implications because there are many examples of protein structures in which the terminal residues are disordered and it is commonly assumed that these are not important for protein stability. The example of Cnm67 provides a cautionary tale for such assumptions.

Last, the results convincingly establish that the addition of folding and solubility domains that maintain the oligomerization state of a coiled-coil protein is a powerful new approach to investigating this class of proteins. This approach has successfully been used to determine the structure of the smooth muscle tropomyosin overlap complex (41) and crystallize fragments of the cardiac myosin rod that have previously resisted crystallization.4 Given that about 6% of all eukaryotic proteins contain coiled-coils (49) and that many of the proteins in this class have been very challenging to study by structural methods, it can be expected that the present work will open new promising avenues of research. It paves the way to pursue the structures of other SPB core proteins and their complexes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Dwight Anderson (University of Minnesota) for the expression vector encoding the scaffolding protein Gp7 from bacteriophage ϕ29. We also thank Kirsten Dennison for help in constructing the Gp7 expression vector and construction of pKLD115 and Sean Newmister for recording the CD spectra. We thank Dr. Hazel Holden for help in the initial model building of Gp-Cnm67. Use of the Structural Biology BM19 beamline Argonne National Laboratory Advanced Photon Source was supported by the United States Department of Energy, Office of Energy Research, under Contract W-31-109-ENG-38.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants GM083987 (to I. R.) and GM051312 (to M. W.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables S1 and S2 and Figs. S1–S5.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 3OA7) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

M. H. Jones and M. Winey, unpublished information.

K. C. Taylor, L. A. Leinwand, and I., Rayment, unpublished information.

- SPB

- spindle pole body

- CHES

- N-cyclohexyl-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid

- HEPPS

- 3-[4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazinyl]propanesulfonic acid

- rTEV

- recombinant tobacco etch virus protease

- SAD

- single wavelength anomalous diffraction

- Ni-NTA

- nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid.

REFERENCES

- 1. Nigg E. A., Raff J. W. (2009) Cell 139, 663–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Doxsey S., McCollum D., Theurkauf W. (2005) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 21, 411–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Adams I. R., Kilmartin J. V. (1999) J. Cell Biol. 145, 809–823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jaspersen S. L., Winey M. (2004) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 20, 1–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bullitt E., Rout M. P., Kilmartin J. V., Akey C. W. (1997) Cell 89, 1077–1086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. O'Toole E. T., Winey M., McIntosh J. R. (1999) Mol. Biol. Cell 10, 2017–2031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Muller E. G., Snydsman B. E., Novik I., Hailey D. W., Gestaut D. R., Niemann C. A., O'Toole E. T., Giddings T. H., Jr., Sundin B. A., Davis T. N. (2005) Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 3341–3352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Elliott S., Knop M., Schlenstedt G., Schiebel E. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 6205–6210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Li S., Sandercock A. M., Conduit P., Robinson C. V., Williams R. L., Kilmartin J. V. (2006) J. Cell Biol. 173, 867–877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Aldaz H., Rice L. M., Stearns T., Agard D. A. (2005) Nature 435, 523–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Al-Bassam J., Larsen N. A., Hyman A. A., Harrison S. C. (2007) Structure 15, 355–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zizlsperger N., Malashkevich V. N., Pillay S., Keating A. E. (2008) Biochemistry 47, 11858–11868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kilmartin J. V., Dyos S. L., Kershaw D., Finch J. T. (1993) J. Cell Biol. 123, 1175–1184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schaerer F., Morgan G., Winey M., Philippsen P. (2001) Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 2519–2533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li Y., Brown J. H., Reshetnikova L., Blazsek A., Farkas L., Nyitray L., Cohen C. (2003) Nature 424, 341–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Li Y., Mui S., Brown J. H., Strand J., Reshetnikova L., Tobacman L. S., Cohen C. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 7378–7383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nitanai Y., Minakata S., Maeda K., Oda N., Maéda Y. (2007) Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 592, 137–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Strelkov S. V., Herrmann H., Geisler N., Wedig T., Zimbelmann R., Aebi U., Burkhard P. (2002) EMBO J. 21, 1255–1266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sibanda B. L., Critchlow S. E., Begun J., Pei X. Y., Jackson S. P., Blundell T. L., Pellegrini L. (2001) Nat. Struct. Biol. 8, 1015–1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Morais M. C., Kanamaru S., Badasso M. O., Koti J. S., Owen B. A., McMurray C. T., Anderson D. L., Rossmann M. G. (2003) Nat. Struct. Biol. 10, 572–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brachat A., Kilmartin J. V., Wach A., Philippsen P. (1998) Mol. Biol. Cell 9, 977–991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chen G. J., Qiu N., Karrer C., Caspers P., Page M. G. (2000) Biotechniques 28, 498–500, 504–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. van den Ent F., Löwe J. (2006) J. Biochem. Biophys Methods 67, 67–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rocco C. J., Dennison K. L., Klenchin V. A., Rayment I., Escalante-Semerena J. C. (2008) Plasmid 59, 231–237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sikorski R. S., Hieter P. (1989) Genetics 122, 19–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lau C. K., Giddings T. H., Jr., Winey M. (2004) Eukaryot. Cell 3, 447–458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Van Duyne G. D., Standaert R. F., Karplus P. A., Schreiber S. L., Clardy J. (1993) J. Mol. Biol. 229, 105–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Blommel P. G., Fox B. G. (2007) Protein Expr. Purif. 55, 53–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gasteiger E., Hoogland C., Gattiker A., Duvaud S., Wilkins M. R., Appel R. D., Bairoch A. (2005) in The Proteomics Protocols Handbook (Walker J. M. ed) pp. 571–607, Humana Press Inc., Totowa, NJ [Google Scholar]

- 30. Otwinowski Z., Minor W. (1997) Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Terwilliger T. C. (2000) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 56, 965–972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Terwilliger T. C., Berendzen J. (1999) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 55, 849–861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Terwilliger T. C., Berendzen J. (1997) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53, 571–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Terwilliger T. C. (2001) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 57, 1755–1762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McCoy A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Adams P. D., Winn M. D., Storoni L. C., Read R. J. (2007) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, 658–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Perrakis A., Harkiolaki M., Wilson K. S., Lamzin V. S. (2001) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 57, 1445–1450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Skubák P., Murshudov G. N., Pannu N. S. (2004) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2196–2201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Morrow J. A., Segall M. L., Lund-Katz S., Phillips M. C., Knapp M., Rupp B., Weisgraber K. H. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 11657–11666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Guthrie C., Fink G. (1991) Methods Enzymol. 194, 1–8632005781 [Google Scholar]

- 41. Frye J., Klenchin V. A., Rayment I. (2010) Biochemistry 49, 4908–4920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lupas A., Van Dyke M., Stock J. (1991) Science 252, 1162–1164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Berger B., Wilson D. B., Wolf E., Tonchev T., Milla M., Kim P. S. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 8259–8263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. McDonnell A. V., Jiang T., Keating A. E., Berger B. (2006) Bioinformatics 22, 356–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wolf E., Kim P. S., Berger B. (1997) Protein Sci. 6, 1179–1189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Krissinel E., Henrick K. (2004) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2256–2268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Holt L. J., Tuch B. B., Villén J., Johnson A. D., Gygi S. P., Morgan D. O. (2009) Science 325, 1682–1686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Slep K. C., Rogers S. L., Elliott S. L., Ohkura H., Kolodziej P. A., Vale R. D. (2005) J. Cell Biol. 168, 587–598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rose A., Schraegle S. J., Stahlberg E. A., Meier I. (2005) BMC Evol. Biol. 5, 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. DeLano W. L. (2010) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.3r1, Schrodinger, LLC, New York [Google Scholar]

- 51. Baker N. A., Sept D., Joseph S., Holst M. J., McCammon J. A. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 10037–10041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.