Abstract

Engagement of the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) receptor complex activates multiple signaling pathways that play crucial roles in both health and disease. TGF-β is a key regulator of fibrogenesis and cancer-associated desmoplasia; however, its exact mode of action in these pathologic processes has remained poorly defined. Here, we report a novel mechanism whereby signaling via members of the ERBB or epidermal growth factor family of receptors serves as a central requirement for the biological responses of fibroblasts to TGF-β. We show that TGF-β triggers upregulation of ERBB ligands and activation of cognate receptors via the canonical SMAD pathway in fibroblasts. Interestingly, activation of ERBB is commonly observed in a subset of fibroblast but not epithelial cells from different species, indicating cell type specificity. Moreover, using genetic and pharmacologic approaches, we show that ERBB activation by TGF-β is essential for the induction of fibroblast cell morphologic transformation and anchorage-independent growth. Together, these results uncover important aspects of TGF-β signaling that highlight the role of ERBB ligands/receptors as critical mediators in fibroblast responses to this pleiotropic cytokine.

Introduction

Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) is a pleiotropic cytokine with important roles in normal development as well as in various types of diseases (1–4). Under normal physiologic conditions, although TGF-β imposes growth inhibition on different cell types (e.g., epithelial and B cells), a function vital to tissue homeostasis (5, 6), it stimulates the growth of fibroblast cells as observed in the context of wound healing (7). In response to chronic cellular insults however, these tightly regulated functions of TGF-β may lose their integrity, giving rise to a variety of physiologic disorders (1–4). Fibrosis and cancer are diseases whose progression is often largely influenced by TGF-β. Excessive fibroblast proliferation, myofibroblast differentiation, and overproduction of extracellular matrix are the most prominent hallmarks of fibrogenesis and desmoplastic reaction in cancer. Of note, TGF-β acts as a master regulator in all of these processes (3). Therefore, deciphering the biochemical mechanisms controlling fibroblast responses to TGF-β will help identify potential therapeutic targets.

TGF-β signaling is initiated at the cell surface through binding of a TGF-β homodimer to the constitutively active type II TGF-β receptor. This association elicits recruitment of the dormant type I TGF-β receptor (ALK5), leading to its phosphorylation in the cytoplasmic juxtamembrane region (8). Following receptor internalization, phosphorylation of the receptor-regulated transcription factors SMAD2 and SMAD3 subsequently ensues, followed by oligomerization with the common mediator SMAD4. These complexes then translocate to the nucleus, where they control gene transcription in concert with other coregulators (9, 10). Activation of the SMAD pathway has been implicated in the regulation of a large repertoire of genes, and a significant part of the phenotypic changes induced by TGF-β has been attributed to SMADs (1–5). Nonetheless, additional noncanonical signaling cascades have been shown to emanate from the TGF-β receptor complex, and these also play critical roles in mediating the biological effects of TGF-β (11). Thus, the cellular responses to TGF-β clearly result from a complex interplay of multiple signaling pathways. Gaining insight into how these various pathways function and cross-talk, as well as the molecular settings under which they operate, may shed light on the mechanisms underlying TGF-β–associated pathologies.

ERBB proteins are members of a family of receptor tyrosine kinases that include ERBB1/epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)/human epidermal growth factor receptor 1 (HER1), ERBB2/Neu/HER2, ERBB3/HER3, and ERBB4/HER4. On ligand binding, these receptors homodimerize/heterodimerize and autophosphorylate on tyrosine residues, thereby facilitating the activation of a large network of signaling pathways. The case of ERBB2 is an exception because this receptor is ligandless but serves as the preferred dimerization partner for other family members. On the other hand, although ERBB3 is devoid of intrinsic kinase activity, it still retains signaling capability due to transphosphorylation by its partners (12, 13). ERBB receptors can interact with a multitude of ligands categorized into three groups according to their binding specificities. Ligands that exclusively bind ERBB1/EGFR include amphiregulin (AREG), epidermal growth factor (EGF), epigen, and TGF-α. β-Cellulin, epiregulin (EREG), and heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor (HBEGF) are more promiscuous and activate ERBB4 in addition to ERBB1. The third group of ligands harbors the neuregulins (NRG1–NRG4), which bind ERBB3 and/or ERBB4 (12, 14).

Several studies have documented the importance of ERBBs in the pathogenesis of fibrosis. For instance, the pharmacologic inhibition of ERBB kinase activity significantly reduced the extent of pulmonary fibrosis in experimental model systems (15, 16). Likewise, conditional expression of the ERBB ligand TGF-α in the lungs of transgenic mice caused pulmonary fibrosis (17), and this could be mitigated by the administration of the ERBB tyrosine kinase inhibitors gefitinib and erlotinib (18). On the other hand, TGF-β was previously shown to trigger the activation of ERBB1 and/or induction of its ligands in endothelial (19) and hepatoma (20) cells. In both cases, signaling via ERBB1 was essential for implementing the biological activity of TGF-β. Because TGF-β has an established role in fibrogenesis (1, 4), these observations led us to hypothesize that ERBB receptors might act as mediators in fibroblast responses to this cytokine. The present study was designed to address this hypothesis. Here, we show that (a) TGF-β induces ERBB ligand expression and receptor activation via the canonical SMAD pathway in fibroblasts, (b) activation of ERBB by TGF-β is cell type specific, and (c) ERBB activation is required for TGF-β–stimulated fibroblast cell morphologic transformation and anchorage-independent growth (AIG). These results expose a novel role of ERBB in regulating profibrotic TGF-β signaling.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

The following cells lines were used in this study: murine fibroblasts (AKR-2B and Swiss-3T3); human fibroblasts [human skin fibroblast (HSF) and IMR-90]; murine (NMuMg), human (HaCaT, HeLa, and MCF-10A), canine [Madin-Darby canine kidney cells (MDCK)] epithelial cells; and mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) derived from Smad2−/− mice. The Smad knockout MEFs and their wild-type (WT) counterpart were provided in 2002 by Dr. Anita Roberts (NIH). Unless indicated otherwise, cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) during the past 5 years and routinely maintained in high-glucose DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone). IMR-90 cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, sodium pyruvate (1 mmol/L), and nonessential amino acids (Cellgro), whereas MEGM (Lonza) was used for MCF-10A cultures. Lines have not been independently authenticated.

In all experiments, cells were grown under reduced serum conditions for 24 hours before being subjected to specific test reagents. Media formulations were as follows: DMEM supplemented with 0.1% FBS (AKR-2B, HaCaT, HeLa, IMR-90, MDCK, MEFs, and Swiss-3T3), DMEM supplemented with 2% FBS (NMuMg), MEM supplemented with 0.1% FBS (HSF), and serum-free MEBM (Lonza; MCF-10A).

Antibodies and other reagents

Anti–phosphorylated AKT (Ser473), anti-AKT, and anti–phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, whereas anti-ERBB1, anti-ERBB2, and anti-ERK1/2 were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Anti–phosphorylated SMAD2 was obtained from Calbiochem, and anti–glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was from Chemicon/Millipore. Anti-ERBB1, anti-phosphotyrosine (Clone 4G10), and anti-SMAD2/3 were both from Upstate/Millipore. Anti-SMAD3 was from Abcam, whereas the phosphorylated Smad3-specific antibody (Immunogen; COOH-GSPSIRCSpSVpS) was generated in our laboratory (21). Human TGF-β was obtained from R&D Systems.

Protein extraction, immunoprecipitation, and Western blotting

Cells were harvested in modified radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer [50 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mmol/L NaCl, 0.25% Na-deoxycholate, 1% IGEPAL CA-630, 1 mmol/L EDTA supplemented with 50 mmol/L NaF, 1 mmol/L Na3VO4, 1 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche)], subjected to one freeze-thaw cycle, and passed through a 27-G needle for three times. Proteins were extracted on ice for >1 hour with occasional gentle vortexing, and debris and insoluble materials were pelleted by centrifugation at 16,060 × g for 10 minutes.

For immunoprecipitation, total protein extracts (400–600 μg) were precleared with protein A-agarose beads (Millipore; 40 μL of 50% slurry) and mixed with 500 μL of 2× immunoprecipitation buffer [20 mmol/L Tris (pH 7.4), 300 mmol/L NaCl, 2% Triton X-100, 1.0% IGEPAL CA-630, 2 mmol/L EDTA, 2 mmol/L EGTA (pH 8.0), supplemented with 50 mmol/L NaF, 1 mmol/L Na3VO4, 1 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and complete protease inhibitor cocktail]. The total volume was subsequently brought to 1 mL using dH2O. The appropriate antibodies were added and incubated overnight (>12 hours). Immune complexes were collected by addition of protein A-agarose beads (40 μL) and incubation for 2 hours at 4°C. Following three rinses in immunoprecipitation buffer, proteins were eluted in 2× protein loading buffer and analyzed by Western blotting according to protocols recommended by the primary antibody manufacturers.

Protein kinase assay

For kinase assays, cells were grown to confluence and serum starved overnight. Cultures were treated as indicated and harvested for protein extraction as described above. Equivalent protein extracts (400–600 μg) were incubated overnight at 4°C with antibody. Immune complexes were collected with protein A-sepharose (Sigma) and washed twice in kinase lysis buffer [50 mmol/L Tris (pH 7.4), 5 mmol/L EDTA, 250 mmol/L NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 50 mmol/L NaF] and twice in kinase buffer [25 mmol/L Tris (pH 7.4), 10 mmol/L MgCl2, and 1 mmol/L DTT] before incubation in 50 μL kinase buffer containing 15 μmol/L ATP, 5 μg myelin basic protein (MBP; Sigma), and 5 μCi/μL [γ32P]ATP. The kinase reaction was allowed to proceed for 10 minutes at 37°C, stopped with 50 μL 2× Laemmli buffer, and following SDS-PAGE visualized by autoradiography.

Reverse transcription-PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). Two micrograms of RNA were reverse transcribed by the SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase system (Invitrogen). Complementary DNAs were subjected to amplification by PCR using the parameters provided in Supplementary Table S1. PCR reagents were from Denville. PCR products were electrophoretically resolved on 2% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. The black-and-white setting of images was inverted to improve the visual detection of DNA bands.

RNA interference

Plasmids (pLKO.1-puro) encoding short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting murine ErbB1, ErbB2, Smad2, and Smad3 were purchased from the Mayo Clinic Jacksonville RNA Interference Technology Resource. The production of lentivirus and the transduction of AKR-2B cells were essentially as described previously (22). Stable clones or cell populations were generated in the presence of 1.5 μg/mL puromycin.

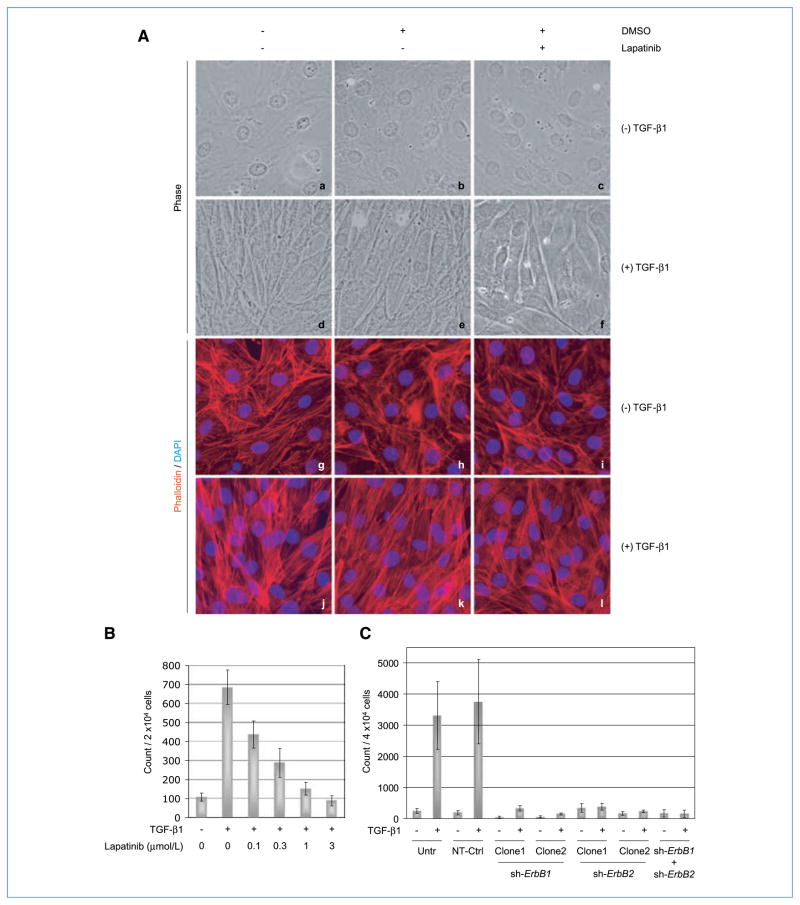

Morphologic transformation

Confluent AKR-2B cells grown on coverslips in six-well tissue culture plates were serum starved for 24 hours and were left untreated or treated with TGF-β1 (10 ng/mL) in the presence or absence of lapatinib (5 μmol/L)/DMSO (vehicle) for 48 hours. AKR-2B cells carrying shRNA targeting ErbB1 and/or ErbB2 or a nontargeting control were processed as above. In all experiments, cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde (20 minutes at 37°C) before permeabilizing with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS (2 minutes on ice) and staining of filamentous actin (F-actin; 1 hour at room temperature) with tetrarhodamine isothiocyanate (TRITC)–labeled phalloidin (Sigma). Nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Photomicrographs were generated using an AX70 fluorescence microscope (Olympus).

Soft agar assay

The experimental conditions for soft agar assay were as described (22). The ability of cells to undergo AIG following TGF-β treatment was evaluated by counting colonies of >50 μm in diameter using a Gelcount apparatus (Oxford Optronics).

Results

TGF-β induces ERBB ligand expression and receptor activation in fibroblasts

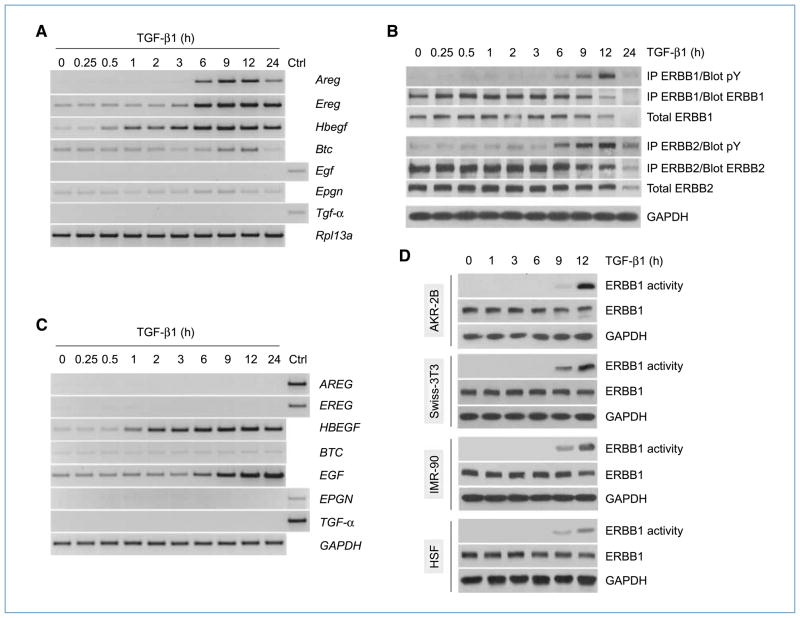

Results from previous studies have suggested a role(s) for ERBB receptors in the pathogenesis of fibrosis (15, 16). Moreover, the ERBB pathway was shown to mediate the biological effects of TGF-β in endothelial and hepatoma cells (19, 20). In light of these observations, we sought to determine whether TGF-β could modulate ERBB ligand expression and/or receptor activation in fibroblast cells. As fibroblasts primarily express ERBB1 and ERBB2 (Supplementary Text S1 and Supplementary Fig. S1), the relevant receptor combinations that could be activated include ERBB1 homodimers and ERBB1/ERBB2 heterodimers (12). Therefore, we focused our subsequent analyses on these two receptors and their known ligands (12). AKR-2B fibroblast cells were stimulated with TGF-β for various periods of time, and the expression of ERBB ligands was evaluated by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR). Our results show that, of the seven ligands tested, only Areg, Ereg, and Hbegf exhibited robust induction by TGF-β (Fig. 1A). To ascertain if TGF-β could activate ERBB receptors, a time course experiment was performed as above, and ERBB1 and ERBB2 were immunoprecipitated and tested for tyrosine phosphorylation. Our results indicate that TGF-β activated both ERBB receptors, with the first detectable increase in phosphorylation occurring between 3 and 6 hours and a peak around 12 hours poststimulation (Fig. 1B). The kinetic of ERBB1/2 activation (Fig. 1B) by TGF-β was similar to that of ligand induction (Fig. 1A) and was significantly delayed relative to direct addition of ERBB ligands (Supplementary Fig. S1B; ref. 12).

Figure 1.

TGF-β induces ERBB ligand expression and receptor activation in mesenchymal cells. A, AKR-2B fibroblast cells were treated with TGF-β (10 ng/mL) and harvested at various time points, and total RNA (2 μg) was subjected to RT-PCR analysis using primers specific for the indicated target genes. Control (Ctrl) sample consisted of mouse heart RNA. B, AKR-2B cells were treated as in A, and total proteins (400 μg) were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) using ERBB1- or ERBB2-specific antibodies. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting using phosphotyrosine (pY)–specific antibodies. Membranes were stripped and reprobed with ERBB1 or ERBB2 antibodies. The expression levels of total ERBB1, ERBB2, and GAPDH (internal control) were assessed by Western blot analysis (50 μg). C, human fibroblast cells (IMR-90) were treated as in A, and total RNA was subjected to RT-PCR analysis for ERBB ligands. Control (Ctrl) sample consisted of human heart RNA. D, murine (AKR-2B and Swiss-3T3) and human (IMR-90 and HSF) fibroblast cells were treated as in A. ERBB1 was immunoprecipitated from total protein extracts (400–600 μg) and subjected to in vitro kinase assays using MBP as a substrate. Total protein aliquots (50 μg) were subjected to Western blot analysis to evaluate the expression levels of total ERBB1 and GAPDH (internal control).

To verify that the observations made in AKR-2B cells could be extended to other fibroblast cells, additional lines were investigated. Results show that Hbegf was upregulated by TGF-β in all cell lines tested (Fig. 1C and Supplementary Fig. S2). However, although induction of Areg and Ereg was restricted to murine fibroblasts (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Fig. S2A), enhanced expression of EGF was observed in addition to HBEGF in their human counterparts (Fig. 1C and Supplementary Fig. S2B). Nonetheless, despite these interspecies variations, TGF-β consistently stimulated activation of ERBB1 in all fibroblast lines as revealed by an increase in kinase activity (Fig. 1D) and/or tyrosine phosphorylation (Supplementary Fig. S2C). These results suggest that the ability to induce ERBB ligand expression and receptor activation in response to TGF-β is a feature commonly shared by fibroblast cells.

Activation of ERBB by TGF-β exhibits cell type specificity

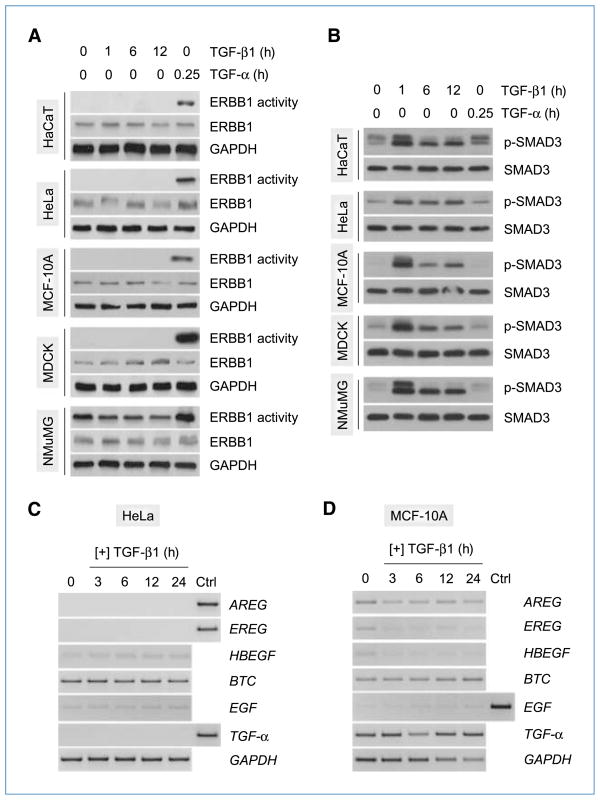

The differential responses of fibroblast and epithelial cells to TGF-β (i.e., growth stimulation versus inhibition, respectively; refs. 5–7) may be explained, at least in part, by the selective activation of cell type–specific pathway(s). We have previously reported that TGF-β activates a network of non-SMAD signaling pathways endowed with proliferative/prosurvival properties and conveying profibrotic effects of TGF-β, only in fibroblast but not in epithelial cells (21, 23–25). Given that ERBB signaling is known to promote cell proliferation and survival (13, 26), we asked whether the common activation of ERBB1 by TGF-β in fibroblasts (Fig. 1D) also displays a similar cell tropism. To address this question, we examined the activation profiles of ERBB1 in a panel of established epithelial lines from different species following treatment with TGF-β for various time periods. Results from in vitro kinase assays show that none of the cell lines tested exhibited a detectable increase in ERBB1 kinase activity in response to TGF-β stimulation for up to 12 hours. In contrast, ERBB1 was activated by TGF-α in all lines, indicating the presence of functional receptors (Fig. 2A). Moreover, the observation that SMAD3 was consistently activated in all cell lines (Fig. 2B) excludes the possibility of dysfunctional TGF-β signaling at the receptor level. As earlier studies documented an inhibitory effect of TGF-β on ERBB ligand expression in epithelial cells (27), we examined the expression profiles of several ERBB ligands in two different epithelial lines treated with TGF-β. Our results show that, although TGF-β caused no discernible effect on ERBB ligand expression in HeLa cells (Fig. 2C), it led to a time-dependent decrease in the mRNA levels of several ERBB ligands (AREG, EREG, and HBEGF) in MCF-10A cells (Fig. 2D). It should be noted, however, that a parallel decline in GAPDH expression (internal control) was also observed, although the levels of TGF-α remained virtually unchanged (Fig. 2D). Overall, these data suggest that ERBB activation is a feature that distinguishes TGF-β signaling in fibroblasts and epithelia.

Figure 2.

Cell type–specific activation of ERBB by TGF-β. A, various epithelial lines from different species were treated with TGF-β (10 ng/mL) and harvested at the indicated times. Cells stimulated with TGF-α (20 ng/mL) for 15 min were used as positive controls for ERBB1 activation. ERBB1 was immunoprecipitated from total protein extracts (400–600 μg) and subjected to in vitro kinase assays using MBP as a substrate. Total protein aliquots (50 μg) were subjected to Western blot analysis to evaluate the expression levels of total ERBB1 and GAPDH (internal control). B, cells were treated with TGF-β or TGF-α as in A, and total proteins (50 μg) were analyzed by Western blotting using antibodies specific for phosphorylated SMAD3 (p-SMAD3) or total SMAD3. C and D, cells were treated with TGF-β (10 ng/mL) and harvested at various time points. Total RNA (2 μg) was subjected to RT-PCR analysis using primers specific for the indicated target genes. Control (Ctrl) sample consisted of human heart RNA.

Induction of ERBB ligands by TGF-β occurs via the SMAD pathway

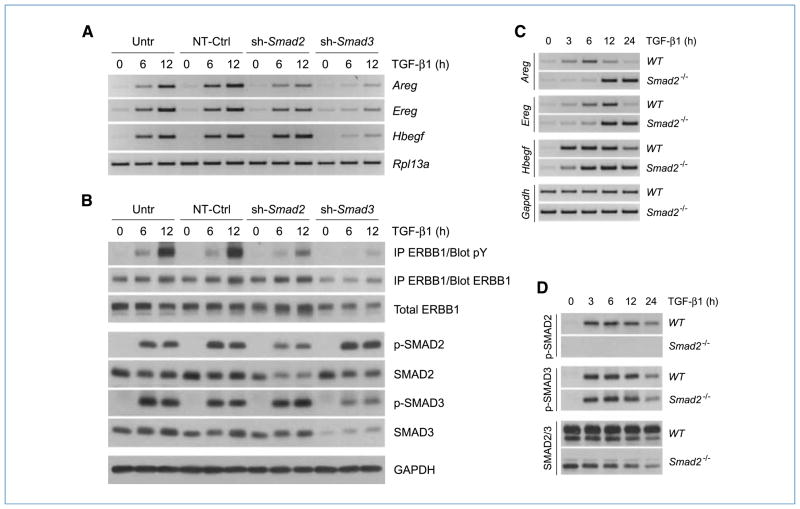

TGF-β primarily exerts its biological effects through the canonical SMAD pathway; however, other non-SMAD pathways have been shown to comodulate cellular response to the cytokine (1–5, 11). To assess the role of SMADs in ERBB ligand induction and receptor activation, AKR-2B cells stably expressing shRNA targeting Smad2, Smad3, or a nontargeting control were treated with TGF-β for different time periods. The induction profiles of Areg, Ereg, and Hbegf as well as the activation of ERBB1 were examined. Results from RT-PCR analyses revealed that TGF-β induced each of the three ligands to comparable levels in untransduced AKR-2B cells and those expressing control shRNA (Fig. 3A). In contrast, inhibition of SMAD2 expression by RNA interference (RNAi) resulted in a slightly reduced induction of Areg and Ereg, no significant effect on Hbegf, and a parallel diminution in TGF-β–dependent ERBB1 and SMAD2 phosphorylation (Fig. 3A and B). The most dramatic effects, however, were observed in Smad3 knockdown cells, in which TGF-β–induced upregulation of all three ligands (Fig. 3A) and phosphorylation of ERBB1 (Fig. 3B) was significantly decreased. It should be noted that, although a satisfactory inhibition of SMAD3 expression was readily achieved (Fig. 3B), we have not been able to obtain further knockdown of SMAD2 beyond that presented (Fig. 3B) without affecting the expression of SMAD3 (data not shown). As such, to more clearly define the contribution of SMAD2, the induction of ERBB ligand expression in Smad2 null MEFs was examined. Although some variation in kinetics was observed between WT and Smad2 knockout lines, loss of SMAD2 had no effect on the induction of Areg, Ereg, or Hbegf (Fig. 3C). As expected, the activation profile of SMAD3 in Smad2−/− cells was comparable with that of WT cells (Fig. 3D). These data indicate that induction of ERBB ligand expression and receptor activation by TGF-β in fibroblasts are dependent on the SMAD pathway, primarily SMAD3.

Figure 3.

Activation of the ERBB axis by TGF-β is SMAD dependent. A, AKR-2B cells stably expressing shRNA targeting Smad2 or Smad3 were treated with TGF-β (10 ng/mL) for 6 or 12 h and harvested for total RNA extraction. Untransduced AKR-2B cells (Untr) and cells transduced with nontargeting sequences (NT-Ctrl) were used as controls. Samples were subjected to RT-PCR analysis using primers specific for Areg, Ereg, or Hbegf. Rpl13a was used as an internal control. B, cells were treated as in A, and total proteins (500 μg) were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) using ERBB1-specific antibodies. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting using phosphotyrosine (pY)–specific antibodies. Membranes were stripped and reprobed with ERBB1 antibodies. Equivalent protein aliquots were subjected to Western blot analysis using antibodies specific for ERBB1, phosphorylated SMAD2 (p-SMAD2), and phosphorylated SMAD3 (p-SMAD3). SMAD2 and SMAD3 antibodies were used to determine silencing efficiency for both genes. GAPDH served as an internal control. C, murine embryonic fibroblast cells, lacking expression of Smad2 (Smad2−/−) as well as the WT counterpart, were treated with TGF-β (10 ng/mL), harvested at various time points, and subjected to RT-PCR analysis using primers specific for Areg, Ereg, or Hbegf. Gapdh was used as an internal control. D, cells were treated with TGF-β as in C, and total proteins (50 μg) were analyzed by Western blotting using antibodies specific for phosphorylated SMAD2 (p-SMAD2), phosphorylated SMAD3 (p-SMAD3), or total SMAD2/3.

TGF-β induces signaling downstream of ERBB

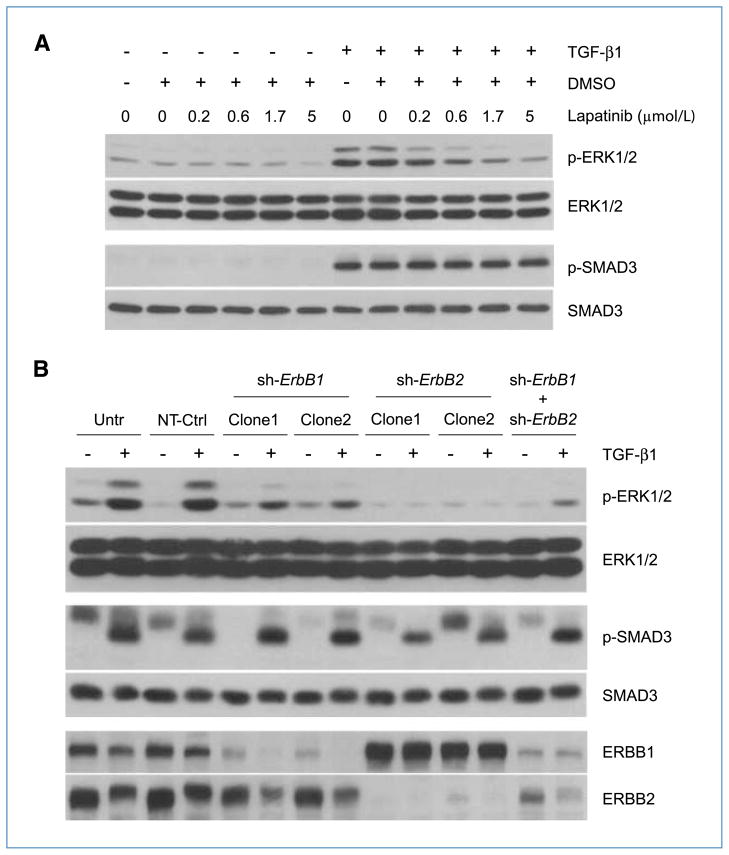

Stimulation of ERBB receptors activates multiple signaling pathways including the mitogen-activated protein kinase–ERK1/2 axis (13). To determine if the activation of ERBB by TGF-β (Fig. 1B) was functionally relevant, we examined whether TGF-β could activate ERK1/2 downstream of ERBB. AKR-2B cells were treated with TGF-β in the presence or absence of the dual ERBB1/2-specific kinase inhibitor lapatinib. Cells were harvested at 12 hours post–TGF-β, when a peak of ERBB1/2 tyrosine phosphorylation was observed (Fig. 1B), and the phosphorylation status of ERK1/2 was evaluated. As shown in Fig. 4A, TGF-β caused an increase in ERK1/2 phosphorylation, which was dose-dependently negated by lapatinib (top row); analogous results were observed with erlotinib and Akt phosphorylation (data not shown). This effect was not due to impaired signaling at the level of the TGF-β receptor complex, as lapatinib (nor erlotinib) did not alter the level of SMAD3 phosphorylation (Fig. 4A, second row from bottom and data not shown, respectively).

Figure 4.

Activation of ERBB by TGF-β elicits downstream signaling. A, AKR-2B fibroblast cells were left untreated or treated with TGF-β (10 ng/mL) for 12 h following a 45-min preincubation with different concentrations of the dual ERBB1/2-specific kinase inhibitor lapatinib or DMSO (0.025%, vehicle). Total proteins (50 μg) were analyzed by Western blotting using antibodies specific for phosphorylated ERK1/2 (p-ERK1/2), total ERK1/2, phosphorylated SMAD3 (p-SMAD3), or total SMAD3. B, AKR-2B cells stably transduced with lentivirus-based shRNA targeting ErbB1 (sh-ErbB1; clones 1 and 2), ErbB2 (sh-ErbB2; clones 1 and 2), or both (sh-ErbB1 + sh-ErbB2) were treated with TGF-β (10 ng/mL) for 6 or 12 h and harvested for total protein extraction. Untransduced AKR-2B cells (Untr) and cells transduced with nontargeting sequences (NT-Ctrl) were used as controls. Equivalent protein aliquots (50 μg) were subjected to Western blot analysis using antibodies specific for phosphorylated ERK1/2 (p-ERK1/2), total ERK1/2, phosphorylated SMAD3 (p-SMAD3), or total SMAD3. ERBB1 and ERBB2 antibodies were used to determine silencing efficiency for both genes. GAPDH served as an internal control. Note: the 6-h samples were used to evaluate SMAD3 phosphorylation, whereas the remaining study was performed on 12-h samples.

To further confirm the functional relevance of ERBB activation by TGF-β, shRNAs targeting ErbB1, ErbB2, or both were stably expressed in AKR-2B cells. Figure 4B shows that, compared with either nontransduced or cells expressing a nontargeting shRNA, inhibition of ERBB1 expression partially prevented activation of ERK1/2 by TGF-β. This is in contrast to ERBB2 silencing, in which TGF-β–stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation was essentially abolished. The partial effect of ERBB1 shRNA is of interest and likely due to (a) the more limited decrease in ERBB1 by RNAi alone (i.e., second row from bottom, lanes 5 and 7) as lanes 6 and 8 reflect the combined effects of shRNA silencing and ligand-induced downregulation/degradation and/or (b) the primary signaling response emanating from ligand-activated ERBB2 heterodimers. Supporting these hypotheses, inhibition of ERBB2 expression was more efficient (first row from bottom) and completely abrogated the activation of ERK1/2 by TGF-β (top row, shErbB2). The data from double knockdown cells (shErbB1 + shErbB2) were also in line with these observations. Thus, the results suggest that activation of ERBB by TGF-β in fibroblasts is functionally relevant and signaling via ERBB in this context may require formation of ERBB1–ERBB2 heterodimers.

TGF-β elicits morphologic transformation and AIG of fibroblast cells via ERBB

Having established the importance of ERBBs in transducing signals originating from the TGF-β receptor complex (Fig. 4), we sought to explore their roles in mediating biological responses of fibroblasts to TGF-β. To this end, we evaluated the effect of ERBB kinase inhibition on morphologic transformation, a phenotypic change associated with TGF-β–induced cytoskeletal alterations characteristic of myofibroblasts (28). AKR-2B cells were treated with TGF-β for 48 hours in the presence or absence of lapatinib, and the effect on cell morphology was analyzed by phase-contrast microscopy. In agreement with previous findings (21, 28), TGF-β stimulation caused “cobblestone”-shaped AKR-2B cells (Fig. 5A, a–c) to adopt a spindle-like, elongated myofibroblastic morphology (Fig. 5A, d and e). In contrast, addition of lapatinib substantially reduced the induction of these morphologic changes by TGF-β (Fig. 5A, f), indicating a role of ERBB1/2 in the process. Interestingly, these modifications were associated with sub-cellular alterations indicative of extensive remodeling of the cytoskeleton, as evidenced by changes in the F-actin structure. Specifically, labeling of F-actin with phalloidin revealed that TGF-β triggered a transition of actin fibers from a disorganized (Fig. 5A, g–i) to a more defined structure (Fig. 5A, j and k), with fibers assuming a parallel orientation along the longitudinal axis of the spindle-shaped cells (Fig. 5A, d and e) in the latter case. Importantly, the formation of these organized structures was significantly impaired in the presence of lapatinib (Fig. 5A, l), suggesting a role of the ERBB pathway in mediating these effects.

Figure 5.

TGF-β induces morphologic transformation and AIG of fibroblasts via ERBB. A, AKR-2B fibroblast cells were grown to confluence on coverslips in six-well tissue culture plates and serum starved for 24 h. TGF-β was added (10 ng/mL) to the cells in the presence/absence of the ERBB1/2-specific kinase inhibitor lapatinib (5 μmol/L) or its vehicle (DMSO, 0.025%) and incubated for an additional 48 h. Following labeling of F-actin with TRITC-conjugated phalloidin (red), photomicrographs (original magnification, 60×) were produced under phase contrast (a–f) or fluorescent light (g–l). DAPI (blue) was used as a nuclear stain. B, AKR-2B cells were grown on soft agar in six-well plates (2 × 104 per well) and left untreated or treated with TGF-β (10 ng/mL) in the presence or absence of different concentrations of lapatinib. Colonies (>50 μm in diameter) were counted at day 14 postseeding. Columns, means of triplicate wells from two separate experiments; bars, SDs. C, AKR-2B cells stably transduced with lentivirus-based shRNA targeting ErbB1 (sh-ErbB1; clones 1 and 2), ErbB2 (sh-ErbB2; clones 1 and 2), or both (sh-ErbB1 + sh-ErbB2) were grown on soft agar in six-well plates (4 × 104 per well) and left untreated or treated with TGF-β (10 ng/mL) for 7 days. Untransduced AKR-2B cells (Untr) and cells transduced with nontargeting sequences (NT-Ctrl) were used as controls. Colonies were counted as in B. Columns, means of three replicates from three separate experiments; bars, SDs.

As ERBBs have a well-documented role in promoting cell proliferation and survival (13, 26), we investigated whether their activation by TGF-β might contribute to the induction of fibroblast cell AIG (22). The ability of AKR-2B cells to form soft agar colonies in response to TGF-β stimulation was assessed in the presence or absence of lapatinib. As shown in Fig. 5B, lapatinib potently counteracted the induction of AIG by TGF-β with maximal inhibition at 1 to 3 μmol/L. The dose dependency of AIG inhibition (Fig. 5B) was comparable with that of ERK1/2 activation (Fig. 4A), which was used as a surrogate marker for ERBB activation (13). These findings were further substantiated by data from experiments using ErbB knockdown cells. Whereas TGF-β–stimulated AIG was dramatically decreased in AKR-2B cells silenced for ErbB1, basal colony formation was also lowered such that a discernible “fold increase” could be argued in the sh-ErbB1 clones. Although the biological significance of this increase is suspected as the counts are similar to non–TGF-β–treated controls, both absolute and fold AIG were fully abolished in ErbB2 and ErbB1+ ErbB2 knockdown cells (Fig. 5C). Together, these results strongly implicate ERBB receptors in mediating biological responses of fibroblasts to TGF-β.

Discussion

It has been proposed that above 45% of all deaths in the Western world can be attributed to some type of chronic fibroproliferative disorder (29). However, as the number of effective therapies is limited, identification of mechanisms regulating biological responses of fibroblasts to TGF-β may provide unique opportunities for therapeutic intervention in fibrosis and various types of desmoplastic cancers (1–4). Here, we report for the first time that ERBBs act as critical mediators of fibroblast responses to TGF-β, thereby introducing a novel conceptual framework for understanding the mechanisms underlying fibrogenesis. Of note, while exposing hitherto unknown aspects of TGF-β–regulated cellular processes in fibroblasts, our findings are consistent with previous observations made by other investigators in distinct biological systems (19, 20).

The striking similarity between the kinetics of ERBB ligand induction and receptor phosphorylation/activation (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. S2) strongly suggests a causative relationship. However, although upregulation of ligands (transcriptional/posttranscriptional) may seem to be the chief mechanism regulating ERBB activation by TGF-β, additional mechanisms are also likely to come into play given the complex biology of ERBB ligands (14, 30). ERBB ligands are synthesized as membrane-tethered precursors, which are processed into mature ligands via proteolytic cleavage by “sheddases” of the “a disintegrin and metalloprotease” (ADAM) family (31). Whether the appropriate sheddase(s) in fibroblasts is (are) constitutively active or coregulated with the ligands by TGF-β is unknown and is the subject of our current investigations. In that regard, the hypothesis of a TGF-β–dependent regulation is supported by the observation that ERBB1 activation was consistently delayed (Figs. 1B and 2B) despite the early induction of one of its ligands, HBEGF (Figs. 1A and 2A and Supplementary Fig. S2). It should also be noted that TGF-β was previously reported to activate ADAM17/tumor necrosis factor-α converting enzyme in mammary epithelial cells (32).

Induction of ERBB ligands by TGF-β is characterized by a cell tropism, occurring in fibroblast but not epithelial cells (Figs. 1 and 2 and Supplementary Fig. S2), and is achieved via the canonical SMAD pathway (Fig. 3). Because our previous studies have shown that several non-SMAD pathways were differentially turned on by TGF-β and controlled specific cellular processes in fibroblasts (21, 23–25), the observation that ERBB activation in fibroblasts displays both cell tropism and SMAD dependency is suggestive of another level of regulation being operative. Although the manner of regulation is currently unknown, epigenetic events that allow preferential induction of ERBB ligands in fibroblasts or that prevent/suppress their expression in epithelial cells may be proposed as a potential mechanism. Such a premise is supported by earlier findings showing that the methylation status of the platelet-derived growth factor B gene promoter dictates the ability of TGF-β to induce expression of this gene and regulate proliferation in glioma cells (33). However, the contribution of non-SMAD pathways (21, 23–25) to ERBB ligand induction in fibroblasts cannot be fully excluded.

This study establishes the role of ERBB receptors in mediating the effect of TGF-β on morphologic transformation and AIG of fibroblasts (Fig. 5). It should be noted, however, that whereas lapatinib prevented both of the aforementioned TGF-β responses (Fig. 5A and B), ERBB1 and/or ERBB2 knockdown was only effective in inhibiting soft agar colony formation (Fig. 5C and data not shown). Although the significance of this is currently not known, it indicates that the actions of TGF-β are regulated by the differing thresholds of ERBB activity. As the importance of TGF-β in fibroproliferative diseases derives from its ability to modulate cellular processes such as myofibroblast differentiation and fibroblast proliferation (3), these observations may have profound in vivo implications. Sustained activation of the ERBB axis by TGF-β may indeed contribute to the induction/maintenance of a myofibroblastic phenotype in fibrotic lesions and during desmoplastic reaction in cancer (1–4). Furthermore, as ERBB inhibitors are most often used in conditions where receptor amplification is observed, the current findings suggest that they may also be effective in tumors with normal ERBB expression whose proliferation and/or invasion is directly activated by these stromal-derived ligands. Additional exploration of the mechanism(s) controlling ERBB activation in each of these contexts will greatly assist efforts to identify potential therapeutic targets.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant Support

Fraternal Order of Eagles Cancer Research Fund (Rochester, MN) fellowship grant (M. Andrianifahanana) and USPHS grants GM-54200 and GM-55816 from National Institute of General Medical Sciences and Mayo Foundation.

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary data for this article are available at Cancer Research Online (http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Derynck R, Akhurst RJ. Differentiation plasticity regulated by TGF-β family proteins in development and disease. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1000–4. doi: 10.1038/ncb434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Massague J, Blain SW, Lo RS. TGFβ signaling in growth control, cancer, and heritable disorders. Cell. 2000;103:295–309. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prud’homme GJ. Pathobiology of transforming growth factor-β in cancer, fibrosis and immunologic disease, and therapeutic considerations. Lab Invest. 2007;87:1077–91. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rahimi RA, Leof EB. TGF-β signaling: a tale of two responses. J Cell Biochem. 2007;102:593–608. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng XH, Derynck R. Specificity and versatility in TGF-β signaling through Smads. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:659–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.022404.142018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heldin CH, Landstrom M, Moustakas A. Mechanism of TGF-β signaling to growth arrest, apoptosis, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:166–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barrientos S, Stojadinovic O, Golinko MS, Brem H, Tomic-Canic M. Growth factors and cytokines in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2008;16:585–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2008.00410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Caestecker M. The transforming growth factor-β superfamily of receptors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2004;15:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ross S, Hill CS. How the Smads regulate transcription. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:383–408. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shi Y, Massague J. Mechanisms of TGF-β signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell. 2003;113:685–700. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00432-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang YE. Non-Smad pathways in TGF-β signaling. Cell Res. 2009;19:128–39. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fuller SJ, Sivarajah K, Sugden PH. ErbB receptors, their ligands, and the consequences of their activation and inhibition in the myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;44:831–54. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.02.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yarden Y, Sliwkowski MX. Untangling the ErbB signalling network. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:127–37. doi: 10.1038/35052073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris RC, Chung E, Coffey RJ. EGF receptor ligands. Exp Cell Res. 2003;284:2–13. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(02)00105-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishii Y, Fujimoto S, Fukuda T. Gefitinib prevents bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:550–6. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200509-1534OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rice AB, Moomaw CR, Morgan DL, Bonner JC. Specific inhibitors of platelet-derived growth factor or epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase reduce pulmonary fibrosis in rats. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:213–21. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65115-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hardie WD, Le Cras TD, Jiang K, Tichelaar JW, Azhar M, Korfhagen TR. Conditional expression of transforming growth factor-α in adult mouse lung causes pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L741–9. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00208.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hardie WD, Davidson C, Ikegami M, et al. EGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors diminish transforming growth factor-α-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;294:L1217–25. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00020.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vinals F, Pouyssegur J. Transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) promotes endothelial cell survival during in vitro angiogenesis via an autocrine mechanism implicating TGF-α signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:7218–30. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.21.7218-7230.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caja L, Ortiz C, Bertran E, et al. Differential intracellular signalling induced by TGF-β in rat adult hepatocytes and hepatoma cells: implications in liver carcinogenesis. Cell Signal. 2007;19:683–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilkes MC, Murphy SJ, Garamszegi N, Leof EB. Cell type-specific activation of PAK2 by transforming growth factor-β independent of Smad2 and Smad3. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:8878–89. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.23.8878-8889.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rahimi RA, Andrianifahanana M, Wilkes MC, et al. Distinct roles for mammalian target of rapamycin complexes in the fibroblast response to transforming growth factor-β. Cancer Res. 2009;69:84–93. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Daniels CE, Wilkes MC, Edens M, et al. Imatinib mesylate inhibits the profibrogenic activity of TGF-β and prevents bleomycin-mediated lung fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1308–16. doi: 10.1172/JCI19603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilkes MC, Leof EB. Transforming growth factor-β activation of cAbl is independent of receptor internalization and regulated by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and PAK2 in mesenchymal cultures. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:27846–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603721200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilkes MC, Mitchell H, Penheiter SG, et al. Transforming growth factor-β activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase is independent of Smad2 and Smad3 and regulates fibroblast responses via p21-activated kinase-2. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10431–40. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henson ES, Gibson SB. Surviving cell death through epidermal growth factor (EGF) signal transduction pathways: implications for cancer therapy. Cell Signal. 2006;18:2089–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomson S, Petti F, Sujka-Kwok I, Epstein D, Haley JD. Kinase switching in mesenchymal-like non-small cell lung cancer lines contributes to EGFR inhibitor resistance through pathway redundancy. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2008;25:843–54. doi: 10.1007/s10585-008-9200-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shipley GD, Childs CB, Volkenant ME, Moses HL. Differential effects of epidermal growth factor, transforming growth factor, and insulin on DNA and protein synthesis and morphology in serum-free cultures of AKR-2B cells. Cancer Res. 1984;44:710–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wynn TA. Common and unique mechanisms regulate fibrosis in various fibroproliferative diseases. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:524–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI31487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schneider MR, Wolf E. The epidermal growth factor receptor ligands at a glance. J Cell Physiol. 2009;218:460–6. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sahin U, Weskamp G, Kelly K, et al. Distinct roles for ADAM10 and ADAM17 in ectodomain shedding of six EGFR ligands. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:769–79. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200307137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang SE, Xiang B, Guix M, et al. Transforming growth factor-β engages TACE and ErbB3 to activate phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase/Akt in ErbB2-overexpressing breast cancer and desensitizes cells to trastuzumab. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:5605–20. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00787-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bruna A, Darken RS, Rojo F, et al. High TGFβ-Smad activity confers poor prognosis in glioma patients and promotes cell proliferation depending on the methylation of the PDGF-B gene. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:147–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.