Abstract

GSIS is often measured in the sheep fetus by a square-wave hyperglycemic clamp, but maximal β-cell responsiveness and effects of fetal number and sex difference have not been fully evaluated. We determined the dose-response curve for GSIS in fetal sheep (0.9 of gestation) by increasing plasma glucose from euglycemia in a stepwise fashion. The glucose-insulin response was best fit by curvilinear third-order polynomial equations for singletons (y = 0.018x3 − 0.26x2 + 1.2x − 0.64) and twins (y = −0.012x3 + 0.043x2 + 0.40x − 0.16). In singles, maximal insulin secretion was achieved at 3.4 ± 0.2 mmol/l glucose but began to plateau after 2.4 ± 0.2 mmol/l glucose (90% of maximum), whereas the maximum for twins was reached at 4.8 ± 0.4 mmol/l glucose. In twin (n = 18) and singleton (n = 49) fetuses, GSIS was determined with a square-wave hyperglycemic clamp >2.4 mmol/l glucose. Twins had a lower basal glucose concentration, and plasma insulin concentrations were 59 (P < 0.01) and 43% (P < 0.05) lower in twins than singletons during the euglycemic and hyperglycemic periods, respectively. The basal glucose/insulin ratio was approximately doubled in twins vs. singles (P < 0.001), indicating greater insulin sensitivity. In a separate cohort of fetuses, twins (n = 8) had lower body weight (P < 0.05) and β-cell mass (P < 0.01) than singleton fetuses (n = 7) as a result of smaller pancreata (P < 0.01) and a positive correlation (P < 0.05) between insulin immunopositive area and fetal weight (P < 0.05). No effects of sex difference on GSIS or β-cell mass were observed. These findings indicate that insulin secretion is less responsive to physiological glucose concentrations in twins, due in part to less β-cell mass.

Keywords: β-cell, glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, pancreas, and twin

the pregnant sheep is a valuable model for multiple pathophysiological processes during pregnancy because placental exchange and fetal physiology can be monitored in utero in conscious animals (3). The tolerance of the uterus to surgical manipulation makes the sheep fetus suitable for chronic catheterization during late gestation, and ample fetal blood volume permits repeated sampling during in vivo studies. Furthermore, commonly used sheep breeds usually have one or two offspring per pregnancy in contrast to other animal models, which often have litters.

In sheep, glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) is present during the second half of gestation (1, 2, 31, 33), and insulin plays a major role in coordinating nutrient availability with fetal growth (11, 18). Although GSIS is routinely measured in the sheep fetus by acute glucose boluses or square-wave hyperglycemic clamps to determine fetal β-cell responsiveness, the dynamic range of glucose-insulin responsiveness has not been characterized. Furthermore, the fetal glucose-insulin dose-response curve is expected to differ from adult subjects because fetal plasma glucose concentrations are lower.

The effect of fetal number on insulin secretion has not been defined, although differences between twins and singletons in other endocrine systems have been shown. Twins are typically smaller at birth than singletons; this is true in both sheep and humans matched for gestational age and is likely the result of fetal competition for maternal resources (39, 42). Twinning is common in sheep, with the majority being dizygotic. Therefore, each fetus has its own distinct placenta and placental vasculature, but the placenta is smaller with fewer placentomes compared with singletons, which can contribute to lower birth weight (42). Previous studies have also shown that twin sheep fetuses have altered adrenocortical responsiveness (13), cardiovascular function (10), and relationships between leptin concentrations and adiposity (8) compared with singleton fetuses. Studies in humans and animals indicate that reduced size at birth is associated with β-cell dysfunction and increased incidence of postnatal metabolic disease, such as type 2 diabetes (15–17). However, it is unclear whether the fetal growth restriction observed in twin pregnancies is associated with changes in insulin secretion in utero.

In this study, we examined the characteristics of fetal sheep insulin secretion responsiveness to glucose. First, we defined the glucose concentration required for maximal stimulation of insulin secretion by conducting step-up hyperglycemic clamps in singleton and twin near-term sheep fetuses. Second, we conducted a retrospective analysis of data previously collected from normal sheep fetuses in our laboratories to evaluate the effects of fetal number and sex difference on near-maximal stimulation of GSIS and pancreas endocrine morphology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fetal sheep preparations.

Columbia-Rambouillet cross-bred ewes carrying singleton or twin pregnancies were purchased from Nebeker Ranch (Lancaster, CA). All animal studies were conducted at the University of Arizona Agricultural Research Complex (Tucson, AZ) or at the University of Colorado (Denver, CO), both of which are accredited by the National Institutes of Health, the US Department of Agriculture, and the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. All animal protocols were submitted to and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at each institution. Ewes had free access to water and were fed alfalfa pellets with a dry matter composition of 19.5% crude protein, 32.6% acid detergent fiber, 42.6% neutral detergent fiber, 1.23 Mcal/kg net energy for maintenance, and 0.66 Mcal/kg net energy for reproductive processes. Ewes were fasted for 24 h prior to surgical procedures. Food intake was recorded daily.

Surgical preparation.

At least 5 days prior to GSIS studies, indwelling polyvinyl catheters were surgically placed in the fetus, as described previously (26, 29). Fetal catheters for blood sampling were placed in the abdominal aorta via hindlimb pedal arteries, and infusion catheters were placed in the femoral veins via the saphenous veins. Maternal catheters were placed in the femoral artery and vein for arterial sampling and venous infusions. All catheters were tunneled subcutaneously to the ewe's flank, exteriorized through a skin incision, and kept in a plastic mesh pouch sutured to the ewe's skin.

Fetal GSIS.

Two types of GSIS studies were used in these experiments, a series of step-up graduated hyperglycemic clamps and single-step square-wave hyperglycemic clamps. For both types of studies, a continuous transfusion of maternal blood into the fetus (6–12 ml/h, depending on sampling frequency) was started 45 min prior to baseline sampling and maintained for the duration of the study to compensate for fetal blood collection and to stabilize fetal hematocrit. For all samples, whole blood collected in syringes lined with EDTA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was centrifuged (13,000 g) for 2 min at 4°C. Plasma was aspirated from the pelleted red blood cells. Plasma glucose concentrations were measured immediately using a YSI model 2700 Select Biochemistry Analyzer (Yellow Springs Instruments, Yellow Springs, OH). Plasma was stored at −80°C until insulin concentrations were measured with an ovine insulin ELISA (intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were 5.6 and 2.9%, respectively; ALPCO Diagnostics, Windham, NH).

For the step-up GSIS studies, a 33% dextrose solution (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL) was infused at a rate sufficient to increase plasma arterial glucose by increments of 0.5 to 1.5 mmol/l up to 4–6 mmol/l. After each incremental increase in dextrose infusion rate, plasma values were allowed to equilibrate for 30 min, and then three samples were collected at steady-state glucose concentrations ∼5 min apart. The step-up GSIS studies were performed on seven singleton fetuses at 134 ± 0.3 days gestational age (dGA; term = 150 days) and eight twin fetuses from four ewes at 134 ± 0.2 dGA. Data were analyzed by plotting plasma glucose concentrations (independent variable) on the x-axis and plasma insulin concentrations (dependent variable) on the y-axis and determining the best-fit model for each fetus.

The square-wave hyperglycemic clamps were conducted as reported previously (26, 29). Briefly, 33% dextrose was given as a bolus (110 mg/kg estimated fetal weight) followed by a constant infusion (10–13 mg·kg−1·min−1) that raised and maintained fetal arterial plasma glucose concentrations at ∼2.4 mmol/l. Baseline plasma glucose and insulin concentrations were determined at −25, −15, and −5 min relative to the initial glucose bolus. Following the glucose infusion, fetal arterial plasma samples were collected every 5–10 min for the initial 30 min to monitor glucose and establish the hyperglycemic clamp at 2.4 mmol/l and at 45, 55, and 65 min at steady-state hyperglycemic conditions. Glucose and insulin concentrations were determined in samples representing the basal (euglycemia; −25 to 0 min) and hyperglycemic clamp (45–65 min) periods. Square-wave hyperglycemic clamp GSIS studies were conducted on 49 singleton (134 ± 0.5 dGA) and 18 twin fetuses (132 ± 0.8 dGA) from 10 ewes that were designated to be uncompromised control fetuses for previously published cohorts (25, 26) and ongoing studies of fetal adaptations to nutritional insults. For the purposes of statistical analyses, data are expressed as means for the basal and hyperglycemic periods, and change in insulin and glucose during the clamp (hyperglycemic-basal) was calculated to indicate GSIS responsiveness. Fetal weight at the time of the GSIS studies was calculated from published growth curves for sheep fetuses (4) on the basis of age and weight at necropsy.

Pancreas morphology.

Pancreas morphology data were collected from seven single and eight twin fetal sheep (from 4 ewes), a group of animals distinct from those used for the in vivo GSIS studies. These animals were also pooled from control, uncompromised animals from previously published (25, 27, 41) or recent unpublished studies that were designed to address different research questions. Ewes were euthanized with intravenous concentrated pentobarbital sodium (10 ml, Sleepaway; Fort Dodge Animal Health, Fort Dodge, IA). Following hysterotomy, the fetus was removed and euthanized with a 1-ml cardiac injection of the same drug. Tissue sections (6 μm) for histological evaluation were cut from the tail of the dissected fetal pancreas. Procedures for fluorescent immunostaining and morphometric analysis on cryosections were performed as reported previously (6, 27). Insulin-positive β-cells were identified with guinea pig anti-porcine insulin (1:500; Dako, Carpinteria, CA) and detected with an affinity-purified secondary antiserum conjugated to 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin-3-acetic acid (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). Fluorescent images were visualized with a microscope system, digitally captured, and analyzed with ImagePro software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD), as described previously (25, 27). Positive areas were determined for 25 fields of view (0.39 mm2) on two to five pancreas sections per animal separated by ≥100-μm intervals (total area ≥19.4 mm2). Data are expressed as a percentage of total pancreas area, and β-cell mass was determined by multiplying the pancreas weight by the percent insulin-positive area.

Statistical analyses.

All data are expressed as means ± SE, and P values <0.05 were considered significant. Glucose-insulin responsiveness data from the step-up GSIS studies were analyzed with Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). For each fetus studied, a third-order polynomial curve was generated to relate the plasma glucose and plasma insulin responses. The glucose concentrations at 100 and 90% of maximum insulin were determined from these curves, and mean and 95% confidence interval values were calculated for the single and twin fetuses. Representative equations reflecting glucose-insulin secretion responsiveness in the single and twin fetuses were generated using the means of terms from the individual fetal curves. For the single step square-wave GSIS studies, all glucose and insulin values used for statistical analyses were averages calculated from three samples taken during a steady-state period (basal and hyperglycemic clamp periods). GSIS and pancreas morphology data were analyzed by ANOVA, initially including both sex difference and fetal number in the model, but the term for sex difference was removed because it was not significant. Calculated fetal weight was also included as a covariate in the analysis of the GSIS data but was not significant, so it was removed from the models. Maternal identification was also included in the statistical models to account for some twin fetuses being from the same ewe. Energy intake was calculated for each ewe and expressed as a percentage of the energy requirement (32). This variable was also used as a covariate in the analyses but was not significant, so it was removed from the statistical model. Linear regression was used to determine correlations between glucose and insulin in the GSIS data and between fetal weight and parameters of pancreas morphology. ANOVA and linear regression analyses were conducted using the Fit Model platform in JMP 8 (SAS, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

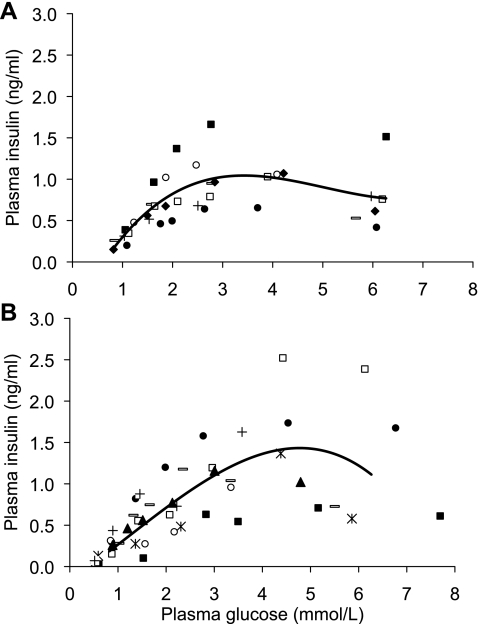

The step-up GSIS studies started at euglycemia (1.03 ± 0.06 and 0.73 ± 0.07 mmol/l, P < 0.05, in single and twin fetuses, respectively) and then incrementally increased fetal plasma glucose to 5.75 ± 0.29 and 6.88 ± 0.60 mmol/l in singles and twins in a total of four to six steps. These studies revealed a glucose-insulin secretion response curve that could be described by third-order polynomial equations, where y is the plasma insulin concentration (ng/ml) and x is the plasma glucose concentration (mmol/l; Fig. 1). The equation for singleton fetuses (n = 7) was y = 0.018x3 − 0.26x2 + 1.2x − 0.64 with a mean r2 value for the seven individual curves of 0.91 ± 0.04. The equation for twin fetuses (n = 8) was y = − 0.012x3 + 0.043x2 + 0.40x − 0.16 with a mean r2 value of 0.96 ± 0.02. Evaluation of the individual fetuses' polynomial curves showed that the maximal plasma insulin response was achieved at 3.4 ± 0.2 mmol/l plasma glucose in singles and 4.8 ± 0.4 mmol/l in twins. Ninety percent of maximum insulin responsiveness occurred at 2.4 ± 0.2 mmol/l plasma glucose in singles and 3.7 mmol/l in twins (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Dose-response curve for insulin responsiveness to glucose in near-term singleton (n = 7; A) and twin (n = 8; B) sheep fetuses. Insulin concentrations were measured during a series of step-up hyperglycemic clamps that increase plasma arterial glucose by increments of 0.5–1.5 mmol/l up to 4–6 mmol/l. Mean third-order polynomial curves calculated from the terms of individual curves generated for the singleton (A) and twin (B) fetuses are shown in addition to the individual values, which are shown as distinct symbols for each fetus. The equation describing the singleton curve is y = 0.018x3 − 0.26x2 + 1.2x − 0.64, and the equation describing the twin curve is y = −0.012x3 + 0.043x2 + 0.40x − 0.16. The mean r2 values for the individual curves are 0.91 ± 0.04 and 0.96 ± 0.02 for singletons and twins, respectively.

Table 1.

Maximal and 90% maximal glucose-insulin responsiveness determined from step-up GSIS studies in near-term singleton and twin fetal sheep

| Singletons (n = 7) | Twins (n = 8) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin | |||

| at 100% of maximum, ng/ml | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | NS |

| at 90% of maximum, ng/ml | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | NS |

| Glucose | |||

| at 100% of maximum, mmol/l (90% CI) | 3.4 ± 0.2 (2.8–3.9) | 4.8 ± 0.4 (3.8–5.8) | 0.031 |

| at 90% of maximum, mmol/l (90% CI) | 2.4 ± 0.2 (2.0–2.8) | 3.7 ± 0.4 (2.9–4.5) | 0.014 |

Values are means ± SE of 7 singleton and 8 twin fetuses of 132–134 days gestational age (dGA). GSIS, glucose-stimulated insulin secretion; NS, not significant. Data were determined from third-order polynomial curves fitted for each fetus.

In singletons, linear regression of the pooled glucose and insulin data revealed a correlation between insulin and glucose when plasma glucose concentrations were <2.4 mmol/l (y = 0.49x − 0.16, where y and x are designated as above; r2 = 0.60, P < 0.001). No linear relationship was found between insulin and glucose when plasma glucose concentrations were >2.4 mmol/l (P = 0.28). Instead, insulin concentrations began to plateau above 2.4 mmol/l glucose and then declined once plasma glucose concentrations exceeded 4 mmol/l (Fig. 1). Similarly, in twins a significant correlation was found between glucose and insulin when glucose concentrations were <3.7 mmol/l (90% of maximum insulin response, described by the equation y = 0.35x − 0.014; r2 = 0.59, P < 0.0001). Above 3.7 mmol/l, no significant correlation was found in twins between glucose and insulin, but insulin concentrations tended to decline with increased glucose (P = 0.10). The slopes of the submaximal regression lines were not different between twins and singletons.

GSIS responsiveness was determined in singleton and twin fetuses with a square-wave hyperglycemic clamp that increased fetal plasma glucose concentrations to ∼2.4 mmol/l, 90% of maximum insulin secretion responsiveness in singletons as determined above in the step-up GSIS studies (Table 1). We selected 2.4 mmol/l as the target plasma glucose concentration for two reasons: 1) the step-up GSIS studies indicate that insulin is dependent on glucose concentrations ≤2.4 mmol/l, because the relationship is linear in both singletons and twins; and 2) exceeding maximal stimulation results in a decline in circulating plasma insulin concentrations in both singleton and twin fetuses (Fig. 1).

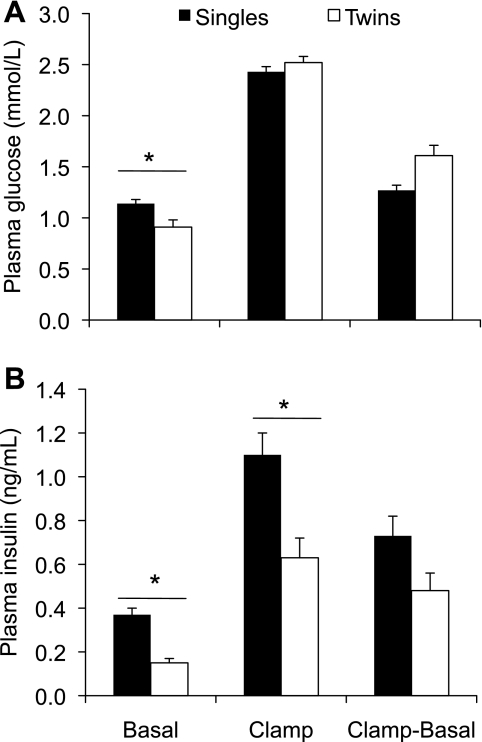

At the time of the square-wave GSIS studies, singleton and twin fetuses were of similar gestational ages, but calculated fetal weight, based on measured weight and age at necropsy, was 17% lower in twins (2.77 ± 0.12 kg; n = 18) compared with singleton fetuses (3.33 ± 0.09 kg; n = 49, P < 0.01). Singletons had higher basal plasma glucose than twins (1.14 vs. 0.91 mmol/l, P < 0.05), but plasma glucose during the hyperglycemic clamp was not different (2.43 vs. 2.53 mmol/l in singles and twins, respectively; Fig. 2A). These glucose concentrations differ (P < 0.01) when expressed as a percentage of that required for maximal insulin stimulation in singles (90.5 ± 2.8%) and twins (62.5 ± 8.0%). Plasma insulin concentrations were 59% lower during the basal period (P < 0.01) and 43% lower during the hyperglycemic steady-state period in twins compared with singleton fetuses (P < 0.05; Fig. 2B). Fetal weight had no effect on basal or stimulated insulin concentrations, indicating that the differences noted were due primarily to fetal number rather than lower fetal weight.

Fig. 2.

Square-wave glucose-stimulated insulin secretion studies in near-term fetal sheep. Plasma glucose (A) and insulin (B) concentrations were measured in singleton [n = 49; 134 ± 0.5 days gestational age (dGA)] and twin (n = 18; 135 ± 0.5 dGA) fetal sheep during basal and hyperglycemic clamp steady states. The differences in glucose and insulin concentrations between the hyperglycemic clamp period and the basal period are also shown. *Significant difference (P < 0.05) between singleton and twin fetuses.

The basal plasma glucose (mmol/l)-to-insulin (ng/ml) ratio was twofold higher (P < 0.001) in twin fetuses (7.94 ± 1.17; n = 18) than in singletons (3.94 ± 0.31; n = 49). In addition to the linear correlation between glucose and insulin ≤2.4 mmol/l glucose described for the step-up experiments, we also found a linear correlation between basal plasma glucose and insulin in the square-wave GSIS cohort (r2 = 0.193, n = 67, P < 0.01). Therefore, plasma insulin concentrations are dependent on plasma glucose concentrations ≤2.4 mmol/l, and this relationship at euglycemia reflects fetal sensitivity to insulin. The higher basal glucose-to-insulin ratio in twin fetuses thus indicates greater insulin sensitivity compared with singleton sheep fetuses. In addition, twin fetuses required a greater mass-adjusted glucose infusion rate (0.78 ± 0.07 g·kg−1·h−1; n = 18) to maintain the square-wave hyperglycemic clamp compared with singleton fetuses (0.63 ± 0.03 g·kg−1·h−1; n = 49, P < 0.05), which also supports improved insulin sensitivity for glucose disposal in twins.

In a second cohort of fetuses, endocrine pancreas morphology was examined to determine whether reductions in β-cell mass contributed to lower insulin secretion in twin fetuses compared with singletons (Table 2). The mean fetal weight was 22% lower (P < 0.05) and mean pancreas weight 36% lower in twins (P < 0.01) compared with singles in this group. Insulin-positive immunofluorescent area was not different between twins and singletons. However, the β-cell mass (insulin area × pancreas mass) was 52% lower in twins (P < 0.05). When singles and twins were pooled (n = 15), positive correlations were observed between fetal weight and pancreas weight (r2 = 0.585, P < 0.001), insulin area (r2 = 0.266, P < 0.05), and β-cell mass (r2 = 0.613, P < 0.001), indicating that fetal weight does play a role in endocrine pancreas morphology. When these parameters were expressed as ratios of fetal weight, twins tended to have lower pancreas weight per body weight (P = 0.054) and had reduced β-cell mass per body weight (P < 0.05). However, no effect was found for fetal number on insulin area per fetal weight. Therefore, the reduction in β-cell mass found in twins was driven by a reduction in pancreas weight, which appeared to exceed that expected by the reduction in fetal mass alone, rather than a change in insulin area. There was no significant effect of sex difference on any of the parameters shown in Table 2, although there was a marginal effect of sex difference on pancreas weight (P = 0.06), because males tended to have greater pancreas weight than females.

Table 2.

Body weight and pancreas morphology parameters in single and twin fetal sheep

| Singletons (n = 7) | Twins (n = 8) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| dGA | 135 ± 0.9 | 135 ± 0.7 | NS |

| Fetal weight, kg | 3.64 ± 0.14 | 2.85 ± 0.17 | 0.012 |

| Pancreas weight, g | 3.82 ± 0.23 | 2.44 ± 0.20 | 0.002 |

| Pancreas weight (g)/fetal weight (kg) | 1.06 ± 0.07 | 0.85 ± 0.05 | 0.054 |

| Insulin area, % | 4.11 ± 0.22% | 3.18 ± 0.61% | NS |

| β-Cell mass, mg | 157.86 ± 14.18 | 75.91 ± 15.81 | 0.007 |

| β-Cell mass (mg)/fetal weight (kg) | 43.44 ± 3.87 | 25.72 ± 4.22 | 0.017 |

Values are means ± SE. The sex difference ratio was different between singletons (males/females was 5/7) and twins (2/8); therefore, sex difference was included initially as a covariate in the statistical model. However, the effect of sex difference was not significant for any test, and it was removed from the statistical model.

DISCUSSION

In the current study, we characterized the dose-response relationship between plasma glucose and insulin concentrations and determined the impact of fetal number and sex difference on insulin secretion in the sheep fetus. The step-up hyperglycemic clamps revealed a curvilinear insulin response to increasing glucose concentrations that is represented by a third-order polynomial curve. Comparison of the glucose-insulin responsiveness curves shows that singletons and twins are able to achieve equivalent maximal insulin concentrations, but twins require higher plasma glucose concentrations (Fig. 1). Insulin concentration is dependent on glucose concentration at 2.4 mmol/l in both singletons and twins. Thus, conducting square-wave clamps at 2.4 mmol/l glucose elicits a physiologically relevant response without risking adverse effects of severe hyperglycemia (Table 1). To further evaluate the potential influences of twinning and sex difference, we examined insulin secretion at 2.4 mmol/l glucose in uncompromised control fetal sheep from several previous or ongoing studies. No effects of sex difference were found, but twin fetuses had lower fetal plasma insulin concentrations during euglycemic and hyperglycemic steady-state periods compared with singletons, which was at least partially explained by lower β-cell mass. The ∼50% lower mean insulin concentrations at basal and hyperglycemic steady-state periods appear to reflect an increased insulin sensitivity in twins, which might serve as an adaption to overcome less β-cell mass (Table 2). However, the ability of twins to reach an equivalent maximum insulin concentration, albeit at higher glucose concentrations, indicates that their β-cells are able to secrete more insulin on a mass basis.

Our best-fit third-order polynomial curves for glucose-insulin responsiveness indicate that glucose concentrations exceeding 3.4 mmol/l in singles and 4.8 mmol/l in twins lead to declines in insulin concentrations. We believe that this finding reflects a physiological response to hyperglycemia rather than β-cell exhaustion. The average duration of hyperglycemia during the step-up studies was 2.3 h, although several studies were completed within 2 h. Even in these shorter studies, we observed decreased insulin at the highest glucose concentrations. In addition, we (Limesand SW and Hay WW Jr, unpublished data) and others (19) have conducted hyperglycemic clamps lasting for 2–4 h at 2.4–3.0 mmol/l in fetal sheep and found no effect of duration of hyperglycemia on steady-state insulin concentrations. On the other hand, plasma norepinephrine was measured for a subset of the fetuses (16 singletons and 8 twins) from the square-wave GSIS cohort in the present study, and we found that inducing hyperglycemia to 2.4 mmol/l raised plasma norepinephrine concentrations (870 ± 227 pg/ml during euglycemia vs. 1,369 ± 382 pg/ml during hyperglycemia; n = 24, P < 0.01), concurrent with reduced blood oxygen content (3.3 ± 0.1 vs. 3.0 ± 0.1 mmol/l; n = 24, P < 0.01). There was no effect of fetal number for this response. At the higher glucose concentrations in the step-up clamps, we expect that hypoxemia and subsequent elevation of plasma norepinephrine concentrations would be further exacerbated (44). These concentrations of norepinephrine may exceed the threshold necessary to inhibit insulin secretion (19, 20, 25, 35), thus providing a physiological explanation for lower insulin secretion when plasma glucose concentrations are raised above 3.4 mmol/l.

The comparison of square-wave GSIS steady-state periods in single and twin fetuses revealed reduced insulin concentrations in twins (Fig. 2). In addition, twins had a 20% reduction in glucose concentrations at euglycemia, which has been shown to blunt insulin secretion responsiveness (26). Lower insulin concentrations can also be partially explained by less β-cell mass (Table 2), which we show is due to lower pancreas weight in twins that tends to be disproportionately greater than the reduction in body weight (Table 2). Indeed, fetal weight was positively associated with pancreas weight, β-cell mass, and insulin area, indicating that fetal growth restriction impacts pancreas morphology or vice versa (15). However, there were additional reductions in pancreas weight and β-cell mass associated with being a twin. Therefore, the ability of twins to respond to a glucose challenge is compromised by a reduced number of β-cells, which is attributed primarily to a smaller pancreas but also might reflect aspects of fetal growth restriction. A similar phenomenon was found in sheep fetuses with placental insufficiency, where intrauterine growth-restricted (IUGR) fetuses had less β-cell mass (27) and impaired GSIS (27, 29). In another placental restriction model of IUGR created by uterine carunclectomy, fetal insulin secretion and β-cell mass positively correlated with fetal weight (34), but β-cell mass was not reduced in IUGR fetuses (14, 34). Although twins are not as severely growth restricted as these other IUGR models, they are subjected to some degree of placental restriction (42). We have recently reviewed β-cell complications resulting from intrauterine growth restriction (15).

Rumball et al. (42) measured insulin secretion in twin and single fetal sheep at 118 dGA using intravenous glucose tolerance tests (IVGTT) and intravenous arginine stimulation tests (IVAST). Similar to our findings, results from this study showed that twin fetuses have lower basal plasma glucose and insulin concentrations compared with singletons. However, twins in their study exhibited greater acute insulin responsiveness to glucose but lower arginine-induced insulin secretion. Our study design differs from this report in two important aspects. First, in the report by Rumball et al. (42), insulin secretion was measured 16 days earlier in gestation compared with our studies at 134 dGA, and it is known that GSIS responsiveness increases by 25% in singleton sheep fetuses during this period (2). Plasma cortisol concentrations are higher in singleton than in twin fetuses between 127 and 146 dGA, and the onset of the prepartum surge in cortisol was shown to occur earlier in singletons (128 dGA) than in twins (135 dGA) (9). Given the maturational effects of fetal cortisol, this difference could delay the maturation of insulin secretion in twins relative to singleton fetuses and explain why insulin secretion was lower in the twins in our study at 134 dGA. Second, the IVGTT used by Rumball et al. (42) measures only acute, first-phase insulin secretion, whereas the square-wave hyperglycemic clamp used in our study assesses second-phase insulin secretion sustained over a 45- to 60-min period (40). Furthermore, fetal glucose concentrations during the IVGTT exceeded our predicted maximum glucose concentration (4.8 mmol/l) for the twin step-up GSIS, indicating that twins are able to achieve equivalent GSIS (Fig. 1). The reduction in IVAST (42) supports the decreased pancreas insulin content (i.e., β-cell mass) we found in twin fetuses (Table 2).

The higher basal plasma glucose/insulin ratio, together with the greater mass-adjusted glucose infusion rate required to maintain hyperglycemia, may indicate greater insulin sensitivity in twins compared with singleton fetuses. Although more direct measurements of insulin sensitivity are warranted, improved insulin sensitivity might be a compensatory response to lower β-cell mass to help maintain rates of glucose utilization in tissues. Placental insufficiency-induced IUGR sheep fetuses also exhibit increased insulin sensitivity and maintenance of fetal mass-specific rates of glucose utilization (28); however, this is not the outcome for all models of intrauterine growth restriction (34). Similarly, increased basal glucose/insulin ratios are also found in small-for-gestational age human fetuses (7) and neonates (5). Thus, increased insulin sensitivity in response to intrauterine nutrient restriction or β-cell dysfunction appears to occur in both sheep and human fetuses.

In this study, we characterized glucose-insulin responsiveness in the late-term sheep fetus, which is best fit by a third-order polynomial equation. On the basis of these findings, we recommend that insulin secretion responsiveness be tested at or above 2.4 mmol/l but not exceeding 3.4 mmol/l. Using this advice, we show that GSIS measured by square-wave clamp is significantly lower in twin compared with singleton fetuses and that this difference was explained partially by reductions in β-cell mass in twins (Table 2) and lower β-cell responsiveness to glucose (Fig. 1). Experimental designs often utilize twins to reduce genetic or environmental variation and to examine complications associated with divergent birth weights. Our data indicate that fetal number impacts insulin secretion and likely insulin sensitivity. These findings suggest that the use of twins for studies of fetal programming of glucose homeostasis may be problematic, and if used, a singleton control group should also be included in the study design (21, 42, 45). This study improves our understanding of insulin secretion responsiveness in the sheep fetus, which continues to serve as a powerful model for studying the effects of pregnancy complications on fetal pancreas development (15).

GRANTS

The project described was supported by Award No. R01-DK-084842 (principal investigator: S. W. Limesand) from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) and an Endocrine Society Bridge Grant (principal investigator: S. W. Limesand). A. S. Green was supported by F32-DK-088514, and both A. S. Green and D. T. Yates were supported by T32-HL-7249.

DISCLOSURES

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases or the National Institutes of Health. No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Mandie M. Dunham, Amy C. Kelly, and David Caprio for their technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1. Adam PA, Teramo K, Raiha N, Gitlin D, Schwartz R. Human fetal insulin metabolism early in gestation. Response to acute elevation of the fetal glucose concentration and placental tranfer of human insulin-I-131. Diabetes 18: 409–416, 1969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aldoretta PW, Carver TD, Hay WW., Jr Maturation of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in fetal sheep. Biol Neonate 73: 375–386, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barry JS, Anthony RV. The pregnant sheep as a model for human pregnancy. Theriogenology 69: 55–67, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Battaglia FC, Meschia G. An Introduction to Fetal Physiology. London: Academic, 1986 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bazaes RA, Salazar TE, Pittaluga E, Peña V, Alegría A, Iñiguez G, Ong KK, Dunger DB, Mericq MV. Glucose and lipid metabolism in small for gestational age infants at 48 hours of age. Pediatrics 111: 804–809, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cole L, Anderson M, Antin PB, Limesand SW. One process for pancreatic beta-cell coalescence into islets involves an epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Endocrinol 203: 19–31, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Economides DL, Proudler A, Nicolaides KH. Plasma insulin in appropriate- and small-for-gestational-age fetuses. Am J Obstet Gynecol 160: 1091–1094, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Edwards LJ, McFarlane JR, Kauter KG, McMillen IC. Impact of periconceptional nutrition on maternal and fetal leptin and fetal adiposity in singleton and twin pregnancies. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 288: R39–R45, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Edwards LJ, McMillen IC. Impact of maternal undernutrition during the periconceptional period, fetal number, and fetal sex on the development of the hypothalamo-pituitary adrenal axis in sheep during late gestation. Biol Reprod 66: 1562–1569, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Edwards LJ, McMillen IC. Periconceptional nutrition programs development of the cardiovascular system in the fetal sheep. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 283: R669–R679, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fowden AL, Hay WW., Jr The effects of pancreatectomy on the rates of glucose utilization, oxidation and production in the sheep fetus. Q J Exp Physiol 73: 973–984, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fowden AL, Hill DJ. Intra-uterine programming of the endocrine pancreas. Br Med Bull 60: 123–142, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gardner DS, Jamall E, Fletcher AJ, Fowden AL, Giussani DA. Adrenocortical responsiveness is blunted in twin relative to singleton ovine fetuses. J Physiol 557: 1021–1032, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gatford KL, Mohammad SN, Harland ML, De Blasio MJ, Fowden AL, Robinson JS, Owens JA. Impaired beta-cell function and inadequate compensatory increases in beta-cell mass after intrauterine growth restriction in sheep. Endocrinology 149: 5118–5127, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Green AS, Rozance PJ, Limesand SW. Consequences of a compromised intrauterine environment on islet function. J Endocrinol 205: 211–224, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hales CN, Barker DJ. The thrifty phenotype hypothesis. Br Med Bull 60: 5–20, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hales CN, Barker DJ, Clark PM, Cox LJ, Fall C, Osmond C, Winter PD. Fetal and infant growth and impaired glucose tolerance at age 64. BMJ 303: 1019–1022, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hay WW, Jr, Meznarich HK, Fowden AL. The effects of streptozotocin on rates of glucose utilization, oxidation, and production in the sheep fetus. Metabolism 38: 30–37, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jackson BT, Cohn HE, Morrison SH, Baker RM, Piasecki GJ. Hypoxia-induced sympathetic inhibition of the fetal plasma insulin response to hyperglycemia. Diabetes 42: 1621–1625, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jackson BT, Piasecki GJ, Cohn HE, Cohen WR. Control of fetal insulin secretion. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 279: R2179–R2188, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jefferies CA, Hofman PL, Knoblauch H, Luft FC, Robinson EM, Cutfield WS. Insulin resistance in healthy prepubertal twins. J Pediatr 144: 608–613, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jensen J, Heller RS, Funder-Nielsen T, Pedersen EE, Lindsell C, Weinmaster G, Madsen OD, Serup P. Independent development of pancreatic alpha- and beta-cells from neurogenin3-expressing precursors: a role for the notch pathway in repression of premature differentiation. Diabetes 49: 163–176, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kervran A, Randon J. Development of insulin release by fetal rat pancreas in vitro: effects of glucose, amino acids, and theophylline. Diabetes 29: 673–678, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kervran A, Randon J, Girard JR. Dynamics of glucose-induced plasma insulin increase in the rat fetus at different stages of gestation. Effects of maternal hypothermia and fetal decapitation. Biol Neonate 35: 242–248, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Leos RA, Anderson MJ, Chen X, Pugmire J, Anderson KA, Limesand SW. Chronic exposure to elevated norepinephrine suppresses insulin secretion in fetal sheep with placental insufficiency and intrauterine growth restriction. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 298: E770–E778, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Limesand SW, Hay WW., Jr Adaptation of ovine fetal pancreatic insulin secretion to chronic hypoglycaemia and euglycaemic correction. J Physiol 547: 95–105, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Limesand SW, Jensen J, Hutton J, Hay WW., Jr Diminished β-cell replication contributes to reduced β-cell mass in fetal sheep with intrauterine growth restriction. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 288: R1297–R1305, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Limesand SW, Rozance PJ, Smith D, Hay WW., Jr Increased insulin sensitivity and maintenance of glucose utilization rates in fetal sheep with placental insufficiency and intrauterine growth restriction. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 293: E1716–E1725, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Limesand SW, Rozance PJ, Zerbe GO, Hutton JC, Hay WW., Jr Attenuated insulin release and storage in fetal sheep pancreatic islets with intrauterine growth restriction. Endocrinology 147: 1488–1497, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Manns JG, Boda JM. Insulin release by acetate, propionate, butyrate, and glucose in lambs and adult sheep. Am J Physiol 212: 747–755, 1967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Molina RD, Carver TD, Hay WW., Jr Ontogeny of insulin effect in fetal sheep. Pediatr Res 34: 654–660, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Research Council Nutrient Requirements of Sheep. Washington, DC: National Academy, 1985 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nicolini U, Hubinont C, Santolaya J, Fisk NM, Rodeck CH. Effects of fetal intravenous glucose challenge in normal and growth retarded fetuses. Horm Metab Res 22: 426–430, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Owens JA, Gatford KL, De Blasio MJ, Edwards LJ, McMillen IC, Fowden AL. Restriction of placental growth in sheep impairs insulin secretion but not sensitivity before birth. J Physiol 584: 935–949, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Padbury JF, Ludlow JK, Ervin MG, Jacobs HC, Humme JA. Thresholds for physiological effects of plasma catecholamines in fetal sheep. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 252: E530–E537, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Philipps AF, Dubin JW, Raye JR. Maturation of early-phase insulin release in the neonatal lamb. Biol Neonate 39: 225–231, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pictet RL, Clark WR, Williams RH, Rutter WJ. An ultrastructural analysis of the developing embryonic pancreas. Dev Biol 29: 436–467, 1972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Piper K, Brickwood S, Turnpenny LW, Cameron IT, Ball SG, Wilson DI, Hanley NA. Beta cell differentiation during early human pancreas development. J Endocrinol 181: 11–23, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Poulsen P, Vaag A. The intrauterine environment as reflected by birth size and twin and zygosity status influences insulin action and intracellular glucose metabolism in an age- or time-dependent manner. Diabetes 55: 1819–1825, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Robertson RP. Estimation of beta-cell mass by metabolic tests: necessary, but how sufficient? Diabetes 56: 2420–2424, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rozance PJ, Crispo MM, Barry JS, O'Meara MC, Frost MS, Hansen KC, Hay WW, Jr, Brown LD. Prolonged maternal amino acid infusion in late-gestation pregnant sheep increases fetal amino acid oxidation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 297: E638–E646, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rumball CW, Harding JE, Oliver MH, Bloomfield FH. Effects of twin pregnancy and periconceptional undernutrition on maternal metabolism, fetal growth and glucose-insulin axis function in ovine pregnancy. J Physiol 586: 1399–1411, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sarkar SA, Kobberup S, Wong R, Lopez AD, Quayum N, Still T, Kutchma A, Jensen JN, Gianani R, Beattie GM, Jensen J, Hayek A, Hutton JC. Global gene expression profiling and histochemical analysis of the developing human fetal pancreas. Diabetologia 51: 285–297, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Stonestreet BS, Piasecki GJ, Susa JB, Jackson BT. Effects of insulin infusion on plasma catecholamine concentration in fetal sheep. Am J Obstet Gynecol 160: 740–745, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Vaag A, Poulsen P. Twins in metabolic and diabetes research: what do they tell us? Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 10: 591–596, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]