Abstract

Oxidative stress plays a role in the pathophysiology of emphysema through the activation of tissue proteases and apoptosis. We examined the effects of ozone exposure by exposing BALB/c mice to either a single 3-h exposure or multiple exposures over 3 or 6 wk, with two 3-h exposures per week. Compared with air-exposed mice, the increase in neutrophils in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and lung inflammation index was greatest in mice exposed for 3 and 6 wk. Lung volumes were increased in 3- and 6-wk-exposed mice but not in single-exposed. Alveolar space and mean linear intercept were increased in 6- but not 3-wk-exposed mice. Caspase-3 and apoptosis protease activating factor-1 immunoreactivity was increased in the airway and alveolar epithelium and macrophages of 3- and 6-wk-exposed mice. Interleukin-13, keratinocyte chemoattractant, caspase-3, and IFN-γ mRNA were increased in the 6-wk-exposed group, but heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) mRNA decreased. matrix metalloproteinase-12 (MMP-12) and caspase-3 protein expression increased in lungs of 6-wk-exposed mice. Collagen area increased and epithelial area decreased in airway wall at 3- and 6-wk exposure. Exposure of mice to ozone for 6 wk induced a chronic inflammatory process, with alveolar enlargement and damage linked to epithelial apoptosis and increased protease expression.

Keywords: airway inflammation, neutrophils, caspase-3, oxidative stress

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a disease characterized by distinct processes in the lungs, namely a chronic inflammatory condition, alveolar damage and destruction (emphysema), and chronic irreversible obstruction of the small airways (37). Although cigarette smoking is the main driver of COPD, other factors may be involved, including a genetic predisposition, other particulates or gases in environmental pollution or exposure to biomass combustion, and bacterial or viral infections (9). Oxidative stress is considered to play an important role in the pathogenesis of COPD since cigarette smoke and particulate exposure are potent inducers of oxidative stress, and there are pathways by which oxidative stress can lead to chronic inflammation and emphysema that have been investigated in mouse models of cigarette exposure (45, 47). The importance of oxidative stress in inducing emphysema has been demonstrated in nuclear factor-E2-related factor-2 (Nrf2) knockout mice, which, through the lack of capacity to mount antioxidant defenses, develop increased susceptibility to emphysema and lung inflammation following cigarette smoke exposure (41).

To expand further on the role of oxidant stress in COPD, we examined the effect of ozone, an environmental pollutant oxidizing gas emanating from petrol combustion engines. Ozone has been used mainly as a single agent exposure in a variety of animal species where it induces a neutrophilic lung inflammation accompanied by airway hyperresponsiveness and has therefore been used mostly as a model for asthma (7, 31, 44). Ozone has been shown to cause the release of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the lungs, such as cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant (CINC), macrophage inflammatory protein-2 (MIP-2), TNF-α, and IL-1β, which may contribute to the lung neutrophilic inflammation (5, 7, 15, 31, 38). Because oxidant stress can induce the activation of proteases (6), we postulated that repeated exposures to ozone could induce emphysema. We therefore examined the effect of repeated exposures to ozone on lung inflammation and structure. We demonstrate that after 6 wk of twice weekly exposure to ozone, mice develop air space enlargement and destruction associated with an increased expression of matrix metalloproteinase-12 (MMP-12) and caspase-3.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ozone exposure.

The experiments were performed within the legal framework of the United Kingdom under a Project License granted by the Home Office of Her Majesty's government. The researchers hold Personal Licenses provided by the Home Office of Her Majesty's government to perform the specific experiments described here. Pathogen-free, 10- to 12-wk-old male BALB/c mice (Harlan) were housed within “maximizer” filter-topped cages (Maximizer; Theseus Caging System, Hazelton, PA). Mice were exposed to ozone produced by an ozonizer (Sander 500 ozonizer; Erwin Sander, Uetze-Eltze, Germany) mixed with air for 3 h at a concentration of 2.5 parts per million (ppm) in a sealed Perspex container. Ozone concentration was continuously monitored with an ozone probe (Analytical Technology, Ashton-under-Lyne, United Kingdom). Ozone exposure was carried out in three groups: 1) single exposure of 3 h; 2) two exposures (every 3 days) per week over 3 wk; and 3) two exposures (every 3 days) per week over 6 wk. Control animals were exposed to air over the equivalent period or over a 3-wk period. Mice were studied 24 h after the last exposure to ozone.

Measurement of inflammation by analysis of BAL fluid.

Following an overdose of anesthetic, mice were lavaged with one 0.8-ml aliquot of PBS via a 1-mm diameter endotracheal tube, and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid was retrieved. Total cell counts and differential cell counts from slide preparations prepared by using a cytospin procedure and stained by Wright-Giemsa stain set (Sigma-Aldrich, Egham, United Kingdom) were determined under an optical microscope (Olympus BH2; Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan). At least 400 cells were counted per mouse and identified as macrophages, eosinophils, lymphocytes, and neutrophils according to standard morphology under ×400 magnification.

The lungs were then dissected out whole following terminal anesthesia with pentobarbitone. The catheter was connected to a PE-90 polyethylene tubing and to a syringe containing 4% paraformaldehyde linked to a manometer. The lungs were thus inflated by injection of the fixative into the lungs maintained to provide 25 cmH2O for at least 4 h. The volumes of the inflated lung were measured by tarring an empty weigh boat and then placing the inflated lungs onto the weigh boat to obtain the weight.

Histological analysis.

Lungs inflated with fresh 4% paraformaldehyde were processed using a histological automatic tissue processor and embedded in paraffin. Paraffin blocks were sectioned to expose the maximum surface area of lung tissue in the plane of the bronchial tree. Five-micrometer sections were then cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin and with Masson trichrome stain, which stains for collagen and smooth muscle. In addition, we used Van Gieson stain to look for mature type 1 collagen. To examine for the presence of goblet cells, we used periodic acid-Schiff reagent.

Alveolar space point counting.

Each entire hematoxylin and eosin-stained section of right lung were “point counted” using an Olympus BH2 light microscope with a ×10 objective lens and an eyepiece graticule containing 100 crosses. Forty fields were counted by scanning three lobes of the right lung in serial microscopic fields, which evenly distributed to cover the entire section. The number of grid points overlying alveolar spaces and interstitial were recorded. Points overlying lumens of large blood vessels were ignored. Proportions of alveolar space were expressed as a percentage of accumulated total of all viable points and calculated using the following formula: percentage of alveolar space area = (number of points overlaying alveolar space ÷ number of points overlaying alveolar space + number of points overlying interstitial tissues) × 100 (2).

Mean linear intercept.

Using a reticule with a Thurlbeck grid comprising 5 lines (each 550 μm long), 10 fields per section were assessed at random. Fields with airways or vessels were avoided by moving 1 field in any 1 direction. The total score for section was determined by counting the number of times the tissue (alveolar wall) intercepted each line. This information was used to calculate the mean linear intercept (Lm) by dividing the length of the line by the number of tissue intercepts counted.

Point counting for airway surface epithelium, collagen, and airway smooth muscle.

The airway wall in Masson-trichrome-stained sections of the right lung were also point counted using ×40 objective lens to assess morphological changes of airway surface epithelium, the amount of collagen deposition, and airway smooth muscle mass. The airway walls of generation 2 and generation 3 or 4 bronchi in each lobe of the right mouse lung were examined. The points overlapping the airway surface epithelium, collagen, and airway smooth muscle of the 3 lobes and 6 sublobes of conducting airways from 3 lobes of each right lung were recorded. About 70 adjacent fields at ×400 magnification along the above airway walls were counted for each mouse. Proportions of each of the above morphological changes were expressed as a percentage of accumulated total of all viable points and calculated using the formula

Lung inflammation score.

The severity of inflammatory response observed in the hematoxylin and eosin-stained lung sections was scored on a 0–3 scale defined as: 0 = no inflammatory response; 1 = mild inflammation with foci of inflammatory cells in bronchial or vascular wall and in alveolar septa; 2 = moderate inflammation with patchy inflammation or localized inflammation in walls of bronchi or blood vessels and alveolar septa, and less than one-third of lung cross-sectional area is involved; and 3 = severe inflammation with diffuse inflammatory cells in walls of bronchi or blood vessels and alveoli septa; between one-third and two-thirds of the lung area is involved.

Immunostaining for apoptosis protease activating factor-1 and active caspase-3.

Lung sections were incubated with peroxidase blocking solution (Dako, Cambridge, United Kingdom). After incubation with rabbit anti-apoptosis protease activating factor-1 [AMS Biotechnology (Europe), Milton Park, Abingdon, United Kingdom] and rabbit anti-active caspase-3 (BD Biosciences, Oxford, United Kingdom) primary antibodies, the sections were incubated with polyclonal goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (cat. no. P0448; Dako) followed by incubation with diaminobenzidine (DAB) liquid and peroxide buffer (Dako). Stained antigen sites were detected as a brown product. Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin and eosin to provide nuclear and morphological detail and then mounted in DPX synthetic resin mountant. Irrelevant rabbit IgG (Sigma-Aldrich) was used for the primary layer as a negative control procedure.

The immunostaining intensity for apoptosis protease activating factor-1 (APA-1) and active caspase-3 in the airway epithelium where it was mostly observed was semiquantitatively given a score ranging from 0 to 3 (0 = negative, 1 = weak staining, 2 = moderate staining, and 3 = strong staining).

All counts on histology sections were performed by two investigators who were unaware of the treatment protocol of the mouse sections.

Reverse transcription and real-time PCR of mouse lungs.

RNA was extracted from frozen stored lung tissue using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and genomic DNA removed by DNase 1 treatment (Qiagen). Half of a microgram per sample of RNA was used to synthesize single-strand cDNA using random hexamers and an avian myeloblastosis virus RT (Promega). The cDNA generated was used as a template in subsequent real-time PCR analyses to determine transcript levels by using Rotor-Gene 3000 (Corbett Life Science) and QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Master Mix Reagent (Qiagen). Sequences of intron-spanning forward and reverse primers for IL-6, keratinocyte-derived chemokine (KC/CXCL1), caspase-3, heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), IFN-γ, and IL-13 were designed using Primer Express software (version 2; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Cycling conditions were as follows: step 1, 15 min at 95°C; step 2, 20 s at 94°C; step 3, 20 s at 55°C; step 4, 20 s at 72°C; repeating steps 2–4 45 times. The standard curves used to determine relative expression for each primer were obtained by running real-time PCR from a serially diluted sample, i.e., 1:1, 1:10, 1:100, and 1:1,000, and gene expression was expressed as a ratio of the gene of interest mRNA to GAPDH mRNA.

Western blot analysis for MMP-12 and caspase-3.

The expression of MMP-12 and caspase-3 was assessed in the lung tissue by performing Western blot analysis using rabbit anti-mouse MMP-12 and anti-mouse caspase-3 antibodies. In brief, 15 μg of total lung protein per lane was separated through 4–12% denaturing polyacrylamide gels (Bis-Tris Novex precast minigel; Invitrogen, Paisley, United Kingdom) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk and then incubated overnight with mouse monoclonal antibody against MMP-12 (cat. no. 52897; Abcam, Cambridge Science Park, Cambridge, United Kingdom) and mouse monoclonal antibody to caspase-3 (cat. no. ab2300; Abcam). An HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit (diluted to 1:2,000; Cell Signaling Technology, Boston, MA) was used as a secondary antibody, and enhanced chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) reagent was used for detection. The bands, which were visualized by chemiluminescent detection on a medical X-ray film, were quantified by scanning densitometric analysis using Grab-It and GelWorks software (UVP, Cambridge, United Kingdom), and finally densitometric data were normalized to β-actin.

Data analysis.

Data are presented as means ± SE. We used one-way analysis of variance to compare the data, and with a significant variance, we performed Bonferroni posttest to compare two individual groups using unpaired t-test. All hypothesis testing was two-sided, and P < 0.05 was accepted as significant.

RESULTS

BAL cells and lung inflammatory scores.

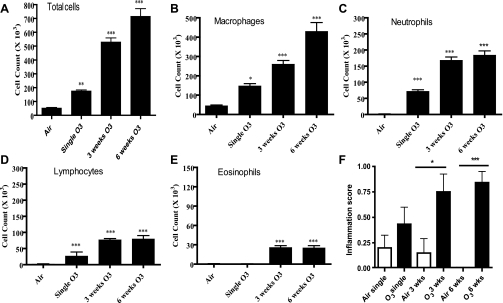

Ozone exposure caused an increase in total cell counts in BAL fluid, as reflected by an increase in neutrophils, lymphocytes, and macrophages (Fig. 1, A–F). These changes were in relation to the duration of exposure to ozone, with the greatest changes in the 6-wk-exposed mice. Interestingly, eosinophils also increased to a lesser extent at 3- and 6-wk exposure (Fig. 1E). We also found increased inflammatory scores in the lungs after exposure to ozone, with significance achieved after 3 and 6 wk (P < 0.05 and P < 0.001, respectively; Fig. 1F).

Fig. 1.

A–E: dose-dependent effect of ozone on total cells, macrophages, neutrophils, lymphocytes, and eosinophils recovered in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid. There were significant increases in macrophages, neutrophils, and lymphocytes after each level of ozone exposure (n = 9 in each group) compared with the air-exposed mice (n = 8). A small increase in eosinophils is also observed after 3 or 6 wk of exposure. F: effect of ozone exposure on inflammation score in the airways and lungs. The inflammation score was increased significantly in the 3- and 6-wk-exposed mice. Data are expressed as means ± SE. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 compared with corresponding air-exposed mice.

Histomorphological changes.

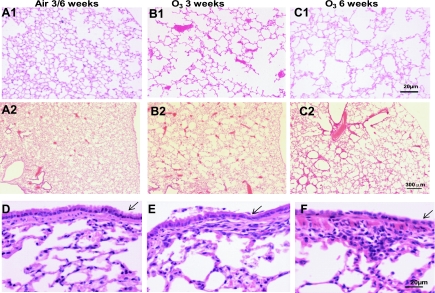

Compared with air control lungs, sections of lungs show necrosis and shedding of airway surface epithelium, foci, or patchy infiltration of inflammatory cells, mainly neutrophils, monocytes, and some lymphocytes, in the walls of airway and blood vessels and alveolar septa in single- and 3-wk ozone-exposed groups (Fig. 2, D–F). There was no evidence of goblet cell hyperplasia. In 6-wk ozone-exposed lungs, a flat single layer of airway epithelium lining was observed (Fig. 2F). Compared with the air control lungs at the same magnification (Fig. 2, A1 and A2), there is irregular enlargement of alveolar spaces and a reduced number of alveolar walls observed in 6-wk ozone-exposed groups (Fig. 2, C1 and C2). In the 3-wk ozone-exposed group, there was a lesser degree of reduction of alveolar space (Fig. 2, B1 and B2).

Fig. 2.

A1, B1, and C1 (high power) and A2, B2, and C2 (low power): representative histological sections of mouse lungs stained with hematoxylin and eosin after exposure to ozone showing enlargement of alveolar space after 3 and 6 wk of exposure. A1 shows lungs from an air-exposed mouse for 3 wk, and A2 an air-exposed mouse for 6 wk. B1 and B2 are representative lung sections from ozone-exposed mice for 3 wk, and C1 and C2 from ozone-exposed mice for 6 wk, showing the degree of alveolar space enlargement. D–F: representative histological sections of mouse airway and lungs stained with hematoxylin and eosin showing the degree of submucosal airway inflammation in the 3- and 6-wk-exposed mice and the flattening of the airway epithelium (arrow) seen particularly after 6 wk of exposure. There is also evidence of enlargement of the alveoli in the ozone-exposed mice.

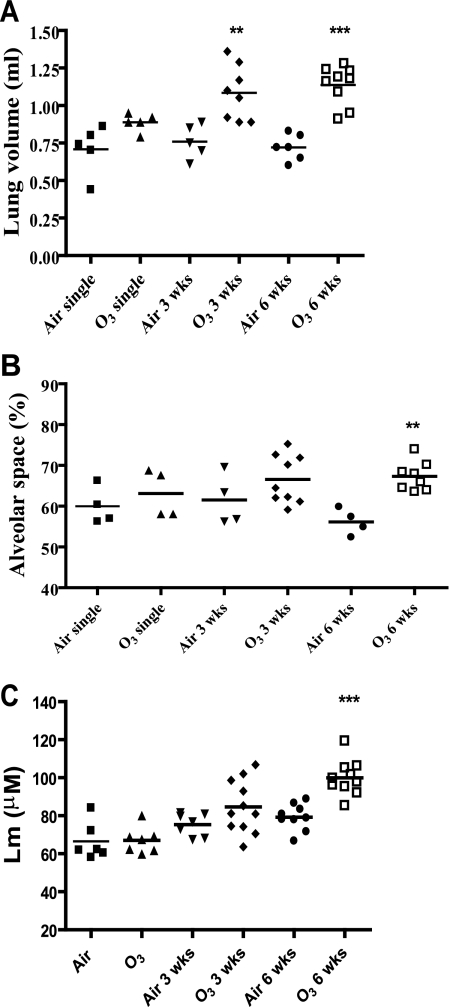

Lung volumes and lung morphometry.

Lung volumes measured by water displacement showed an increase with duration of exposure to ozone, achieving statistical significance after 3 and 6 wk of exposure, with no significant changes after single exposure (Fig. 3A). Using point counting regarding the percentage of alveolar lung space, the mean area of alveolar space was increased from 56.13 ± 1.60% in 6-wk air-exposed mice to 67.31 ± 1.27% in 6-wk ozone-exposed mice (P < 0.05). No significant changes in alveolar space were observed in single- or 3-wk-exposed mice compared with their respective air-exposed controls (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

A: effect of ozone exposure on lung volumes of lungs inflated to 25 cmH2O. Total lung volumes were significantly increased in mice exposed to ozone for 3 and 6 wk compared with appropriate air-exposed and single-exposed mice. B and C: morphometric measurements of alveolar space enlargement (B) and mean linear intercept (Lm; C) in mice exposed to ozone or air. Lungs inflated at 25 cmH2O were sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin and microscopically assessed for the alveolar space by point counting and for Lm. There was a significant increase after 6 wk of ozone exposure in the alveolar space enlargement and in Lm compared with their appropriate air-exposed control. There were no significant changes in the alveolar space enlargement or in Lm of mice after single or 3-wk exposure compared with their air-exposed controls. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared with appropriate air control.

Lm was increased significantly in 6-wk-exposed mice compared with air-exposed controls (79.23 ± 2.31 vs. 99.90 ± 2.91 μm; P < 0.0001) but not in single- or 3-wk ozone-exposed mice (66.53 ± 4.04 vs. 67.05 ± 2.58 μm, not significant; 75.33 ± 2.24 vs. 84.61 ± 4.20 μm, P = 0.07, respectively; Fig. 3C). Thus these changes indicate that the 6-wk-exposed mice showed an increase in alveolar size associated with an increase in lung volumes. These changes are accompanied by visible space enlargement by 6 wk of exposure (compare Fig. 2, A1 and A2, with C1 and C2).

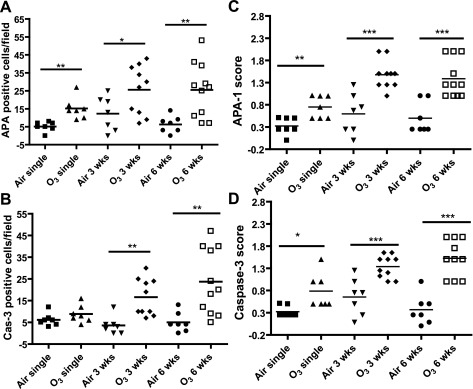

Expression of APA-1 and caspase-3.

Both APA-1 and active caspase-3 were expressed focally and weakly in airway surface epithelium of air control airways but were moderately to strongly expressed in the epithelium of 3- and 6-wk ozone exposures (Fig. 4, I and J), and in the lungs, there was also expression in alveolar type II epithelial cells and monocytes/macrophages (Fig. 4, I–L). In contrast, there were very few positive cells in lung parenchyma of air control mice. The scores of positive cells in lung sections and of immunostaining intensity of epithelial positive cells are shown in Fig. 5. APA-1-positive cells were significantly increased at all levels of ozone exposure with the greatest effects observed after 3 and 6 wk of exposure. Caspase-3-positive cells increased significantly after 3 and 6 wk of exposure to ozone. In addition, immunostaining intensities for APA-1 and caspase-3 were increased after all levels of exposures to ozone (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Immunohistochemical analysis of the expression of apoptosis protease activating factor-1 (APA-1) and active caspase-3 in airway epithelium of mice exposed to ozone once for 3 or 6 wk (A–H). Air-exposed mice showed no staining, but there was greatest staining for both APA-1 and caspase-3 in flattened epithelial cells of 6-wk-exposed mice. I–L shows staining in the alveolar epithelium and alveolar macrophages of lungs from 6-wk-exposed mice.

Fig. 5.

A and B: number of positive APA-1 and caspase-3 (Cas-3) cells counted in the lung parenchyma mainly in airway and alveolar epithelial cells and macrophages were increased after 3 and 6 wk of exposure compared with air-exposed controls. C and D: immunostaining scores of staining for APA-1 and caspase-3 in airway epithelial cells of ozone-exposed lungs. Data are expressed as means ± SE. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Airway wall remodeling features.

Using point counting, we determined the relative contribution of the epithelium, collagen, and airway smooth muscle to the bronchial airway wall area. Whereas single ozone exposure did not change the relative proportion of these constituents of the airway wall, after 3 and 6 wk exposure, the relative contribution of collagen increased associated with a decrease in the area of epithelium (Fig. 6). The increase in collagen was most marked after 6 wk of exposure, corresponding to the increased subepithelial collagen as visualized on Masson trichrome stain, shown in Fig. 7, A–C. In addition, we used Van Gieson staining for mature type 1 collagen to confirm the increase in subepithelial collagen in the airways after 3 and 6 wk of exposure to ozone (Fig. 7, D–F). The reduction in epithelial surface area correlates well with the appearance of flattening of the epithelium observed at 6 wk of ozone exposure (Figs. 2F and 7C). The airway smooth muscle area showed a nonsignificant proportional increase at 3 but not 6 wk. We did not notice any increase in goblet cells in the sections and confirmed this by using periodic acid-Schiff staining (data not shown).

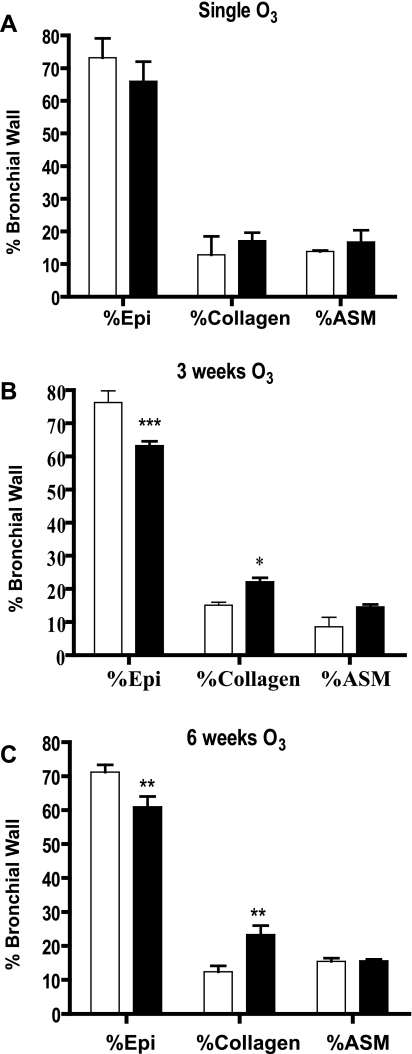

Fig. 6.

Effect of single (A), 3 wk (B), and 6 wk (C) of either air (open bars) or ozone (shaded bars) exposure on relative epithelial (Epi), collagen, and airway smooth muscle (ASM) area in the bronchial wall measured by point counting of slides stained with Masson trichrome. There is a relative reduction in epithelial area with an increase in collagen after 3 and 6 wk of exposure to ozone. n = 6 For each group. Data are expressed as means ± SE. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared with air-exposed.

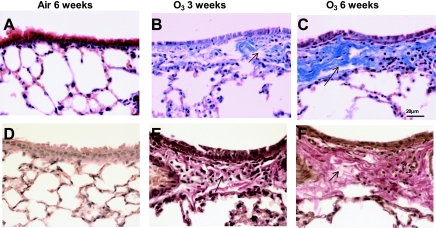

Fig. 7.

A–C: representative histological sections of airways stained with Masson trichrome showing the presence of submucosal deposition of collagen as indicated by the blue staining (arrows) and flattening of the airway epithelium particularly intense after 3 and 6 wk of exposure to ozone. Note also the presence of alveolar damage in the 3- and 6-wk-exposed mice. D–F: representative histological sections of airways stained with Van Gieson stain for the presence of mature collagen in the airway submucosa as indicated by red staining (arrows). There is increased collagen deposition at 3- and 6-wk-exposed mice, with little evidence of collagen in air-exposed mice.

Lung gene and protein expression.

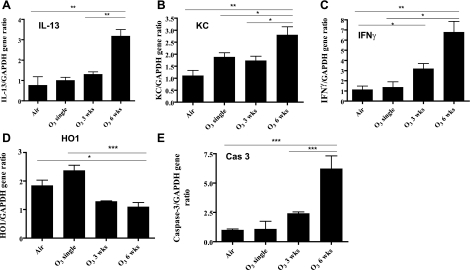

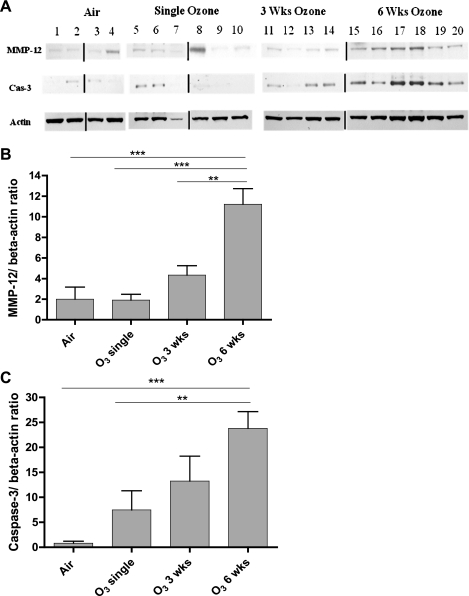

There was a significant increase in the expression of IFN-γ, IL-13, KC, and caspase-3 mRNA as measured by RT-PCR in mouse lungs of 6 wk ozone-exposed lungs compared with single- or 3-wk ozone-exposed lungs (Fig. 8). On the contrary, HO-1 expression fell by ∼2-fold in 3- and 6-wk-exposed lungs. Using Western blot analysis, we confirmed the increased expression of MMP-12 and active caspase-3 in 6-wk-exposed lungs (Fig. 9), although the expression also increased nonsignificantly after 3 wk of exposure.

Fig. 8.

A–E: effect of ozone exposure on lung IL-13, keratinocyte-derived chemokine (KC/CXCL1), IFN-γ, heme-oxygenase-1 (HO-1), and caspase-3 gene expression measured by RT-PCR. The expression of IL-13, KC, IFN-γ, and caspase-3 was increased significantly after 6 wk of ozone (n = 8) compared with air-exposed controls (n = 4), with nonsignificant increases in these genes at 3 wk (n = 4). HO-1 gene expression decreased after 3 and 6 wk of ozone exposure, reaching significance at 6 wk. There was no significant effect on these genes after 1 exposure to ozone (n = 4), although there was a nonsignificant increase in KC and HO-1. Data are expressed as means ± SE. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Fig. 9.

A: Western blot analysis of protein extracts of ozone-exposed mouse lungs compared with the air-exposed mouse lungs for matrix metalloproteinase-12 (MMP-12), activated caspase-3, and β-actin. Because the samples were run on different gels, the blots were spliced to be presented in the correct order. The vertical lines indicate where the blots were spliced. B and C: mean densitometric values of MMP-12 and caspase-3 expression as a ratio of β-actin expression. Expression of both MMP-12 and caspase-3 was increased in 6-wk ozone-exposed mice, with nonsignificant increase in expression after 3-wk exposure. The levels of β-actin protein were not significantly different under air or ozone exposure. Data are expressed as means ± SE. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

We showed that exposure to ozone (2.5 ppm) for 3 h for a couple of times per week over a 6-wk period induced alveolar space enlargement in mice as measured by an increase in lung volume, alveolar space size, and Lm, effects that were not present in mice after a single exposure to ozone. In mice exposed to ozone for 3 wk, there was an increase in lung volumes without significant increases in alveolar space size or Lm. This may reflect a greater sensitivity of lung volumes to detect emphysema. By 3 wk, the process of emphysema had started, reaching a maximal effect by 6 wk. Other abnormalities were present as early as after a single exposure such as inflammatory cells including neutrophils in BAL fluid and lung parenchymal inflammation as quantified by an inflammatory score. Expression of cytokines such as IL-13 and IFN-γ known to be involved in mouse emphysema models (50, 56) was increased particularly after 6 wk of exposure, as were the expression of the protease MMP-12 and the apoptotic enzymes caspase-3 and APA-1, also known to be involved in mouse emphysema models (45, 47). The presence of lung emphysema contrasted with the presence of fibrosis in the airways as assessed by the level of collagen, thus mimicking the pathological changes described in small airways of COPD (19). We have therefore shown that chronic exposure to an oxidant stress gas, ozone, can induce emphysema, producing a model of COPD.

Cigarette smoke exposure of rodents has remained a model of choice for inducing emphysema, since cigarette smoking is the most common cause of emphysema. The chronic ozone exposure model, however, possesses many similarities with the cigarette exposure models and also represents an oxidant-induced model of emphysema. Emphysema-like lesions develop in mice following exposure to cigarette smoke delivered on a daily basis, usually needing 3–6 mo of exposure, and to some extent, this response is strain-dependent (4, 14, 35). Alveolar destruction may be mediated via macrophages through the activation of macrophage elastase or MMP-12 (16), and both macrophage numbers and MMP-12 expression were upregulated in our 6-wk ozone-exposed mice. Both MMP-12 and elastin fragments generated by MMP-12 may contribute to the accumulation of macrophages and the pathogenesis of cigarette smoke-induced emphysema (16, 21). Although we did not measure antiprotease expression in the lungs of ozone-exposed mice, a previous study has shown that ozone exposure induces a 35–80% decrease in antiprotease activity in lung tissue (39), which would be another factor contributing to emphysema. In the cigarette smoke exposure model, neutrophil recruitment occurs immediately following the beginning of tobacco smoke exposure and is followed by accumulation of macrophages; the early influx of neutrophils is paralleled by connective tissue breakdown, with an increase in elastin and collagen degradation that can be prevented by pretreatment with a neutrophil antibody or α1-antitrypsin (11). In the neutrophil elastase model of emphysema, there is evidence of an acute inflammatory response with emphysema developing within 14 days of the insult (11), indicating the potential for neutrophils to contribute to the emphysematous damage. Similarly, in our model of ozone exposure, neutrophilic and macrophage increases in the lungs occur fairly rapidly within the first exposure and in a more rapid fashion than that caused by cigarette smoke exposure.

A previous study with chronic ozone exposure has not been able to reproduce the development of emphysema in B6C3F1 mice exposed to ozone daily for up to 52 wk, despite the presence of persistent neutrophilic inflammation in the lungs. However, this exposure was at a low level of 0.3 ppm (36), and it is therefore likely that high levels of ozone that we used are necessary for the development of emphysema. The B6C3F1 strain is susceptible to emphysema following exposure to cigarette smoke, making it less likely to be due to strain susceptibility (36). Preliminary data from our laboratory indicate that the C57BL/6J strain is also susceptible to emphysema induced by ozone exposure, with a similar degree of injury as reported in the BALB/c strain.

A number of cytokines have been implicated in the pathogenesis of emphysema in mouse models. For example, overexpression of IL-13 and IFN-γ using inducible conditional transgenes led to emphysema in mice (50, 56). Overexpression of IL-13 resulted in inflammation and lung destruction that was MMP-9- and -12-dependent, and MMP-12 has been shown to underlie cigarette-induced emphysema in mice (16). With more specific relevance to the effect of ozone, we have previously shown that IL-13 is involved in ozone-induced lung neutrophilic inflammation and also enhances the neutrophilic inflammation (54). Conditional overexpression of IL-1β via Clara cell secretory protein promoter led to pulmonary inflammation, increased air space enlargement, airway fibrosis, and increased MMP-9 and -12 levels (33), and IL-1β may play a role in the neutrophilic inflammation induced by ozone exposure (24, 52). Furthermore, acute cigarette exposure results in LPS-independent TLR4 activation, leading to IL-1 production and IL-1R1 signaling (13); in addition, ozone exposure also activates TLR2 and TLR4, and the recruitment of neutrophils into the lungs was dependent on MyD88 signaling (53).

The role of apoptosis in COPD has been studied in lung tissue sections. An increase in endothelial cell apoptosis in lung tissues of COPD has been described, together with increased numbers of apoptotic alveolar epithelial cells, interstitial cells, and inflammatory cells (22, 25, 43, 55), associated with an increase in activated subunits of caspase-3 and loss of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 (22). This is in line with the previous demonstration of apoptosis of alveolar macrophages and epithelial cells being induced after exposure to ozone (28, 30). Expression of VEGF and VEGF receptor 2 protein and mRNA was significantly reduced in emphysema, and, since these are maintenance factors for endothelial cells, a reduction may lead to endothelial alveolar septal death (25). Markers of oxidative stress and apoptosis, such as activated caspase-3, were colocalized in the central portion of the alveolar lobule in emphysema caused by VEGF receptor blockade (25). In our ozone study, we showed that there was evidence of apoptosis of airway and alveolar epithelial cells together with tissue macrophages. APA-1, cytochrome c, and caspase-9 form part of the apoptosome caspase activation complex, which functions to activate caspase-3. Therefore, we examined the expression of APA-1, which is a caspase-activating protein, and of caspase-3 that were upregulated by week 3 of exposure, associated with the increase in lung inflammatory scores. This increase in caspase-3-positive cells also coincided with the increase in caspase-3 mRNA in lung tissues, significant at 6 wk. A single instillation of caspase-3 into the lungs of mice induced alveolar space enlargement (3).

The increase in extracellular matrix in COPD has been described as being more diffuse throughout the airway mucosal surface, with an increase in total collagen I and III in the surface epithelial basement membrane, bronchial lamina propria, and adventitia (32). There is also an increase in matrix deposition in the adventitial compartments of the small airways (1, 10, 19). Our data indicate that there is a significant increase in collagen in the airway wall, although there is evidence of alveolar destruction, as described in COPD. Of interest also is the appearance of a flatter airway epithelial cell; the underlying process is unclear but is unlikely to represent squamous metaplasia.

Finally, although we have not directly measured oxidative stress in our model, there is ample evidence showing that exposure to ozone does so. Thus ozone exposure leads to the production of lipid ozonation products such as aldehydes, hydroxyhydroperoxides, and hydrogen peroxide (40) in addition to F2-isoprostane levels (49). One of the aldehydes formed during ozone exposure, 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal, also a component of cigarette smoke, contributes to lung injury through apoptotic mechanisms (28). A significant oxidative stress-induced transcript measured in this study is the Nrf2-regulated HO-1 gene, which has been shown to be reduced in the cigarette-exposed mouse models and in patients with COPD (34, 42). We observed some biphasic kinetics of HO-1 gene expression with a reduction in the transcript as a result of the chronic effect of ozone after 3 and 6 wk but with a nonsignificant rise in expression after a single ozone exposure.

In summary, this model of emphysema and lung inflammation resulting from repeated exposures to an oxidant gas, ozone, bears many similarities to cigarette smoke exposure model in mice and cigarette-smoke-induced COPD in humans.

GRANTS

This work was funded by Wellcome Trust Project Grant 083905 to K. F. Chung.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Yusheng Qiu and Radhika Anand for their technical contribution and Michael Salmon for advice and help in setting up the model.

REFERENCES

- 1. Adesina AM, Vallyathan V, McQuillen EN, Weaver SO, Craighead JE. Bronchiolar inflammation and fibrosis associated with smoking. A morphologic cross-sectional population analysis. Am Rev Respir Dis 143: 144–149, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aherne WA, Dunnill MS. Point counting and morphometry. In: Morphometry, edited by Aherne WA, Dunnill MS. London: Arnold, 1982, p. 33–35 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aoshiba K, Yokohori N, Nagai A. Alveolar wall apoptosis causes lung destruction and emphysematous changes. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 28: 555–562, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bartalesi B, Cavarra E, Fineschi S, Lucattelli M, Lunghi B, Martorana PA, Lungarella G. Different lung responses to cigarette smoke in two strains of mice sensitive to oxidants. Eur Respir J 25: 15–22, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bhalla DK, Reinhart PG, Bai C, Gupta SK. Amelioration of ozone-induced lung injury by anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Toxicol Sci 69: 400–408, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bolser DC, Davenport PW, Golder FJ, Baekey DM, Morris KF, Lindsey BG, Shannon R. Neurogenesis of cough. In: Cough: Causes, Mechanisms and Therapy, edited by Chung KF, Widdicombe JG, Boushey HA. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2003, p. 173–180 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cho HY, Zhang LY, Kleeberger SR. Ozone-induced lung inflammation and hyperreactivity are mediated via tumor necrosis factor-α receptors. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 280: L537–L546, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chung KF, Adcock IM. Multi-faceted mechanism in COPD: inflammation, immunity & tissue repair and destruction. Eur Respir J 31: 1334–1356, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cosio M, Ghezzo H, Hogg JC, Corbin R, Loveland M, Dosman J, Macklem PT. The relations between structural changes in small airways and pulmonary-function tests. N Engl J Med 298: 1277–1281, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dhami R, Gilks B, Xie C, Zay K, Wright JL, Churg A. Acute cigarette smoke-induced connective tissue breakdown is mediated by neutrophils and prevented by alpha1-antitrypsin. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 22: 244–252, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Doz E, Noulin N, Boichot E, Guenon I, Fick L, Le Bert M, Lagente V, Ryffel B, Schnyder B, Quesniaux VF, Couillin I. Cigarette smoke-induced pulmonary inflammation is TLR4/MyD88 and IL-1R1/MyD88 signaling dependent. J Immunol 180: 1169–1178, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guerassimov A, Hoshino Y, Takubo Y, Turcotte A, Yamamoto M, Ghezzo H, Triantafillopoulos A, Whittaker K, Hoidal JR, Cosio MG. The development of emphysema in cigarette smoke-exposed mice is strain dependent. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 170: 974–980, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Haddad EB, Salmon M, Koto H, Barnes PJ, Adcock I, Chung KF. Ozone induction of cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant (CINC) and nuclear factor-kB in rat lung: inhibition by corticosteroids. FEBS Lett 379: 265–268, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hautamaki RD, Kobayashi DK, Senior RM, Shapiro SD. Requirement for macrophage elastase for cigarette smoke-induced emphysema in mice. Science 277: 2002–2004, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hogg JC, Chu F, Utokaparch S, Woods R, Elliott WM, Buzatu L, Cherniack RM, Rogers RM, Sciurba FC, Coxson HO, Pare PD. The nature of small-airway obstruction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 350: 2645–2653, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Houghton AM, Quintero PA, Perkins DL, Kobayashi DK, Kelley DG, Marconcini LA, Mecham RP, Senior RM, Shapiro SD. Elastin fragments drive disease progression in a murine model of emphysema. J Clin Invest 116: 753–759, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Imai K, Mercer BA, Schulman LL, Sonett JR, D'Armiento JM. Correlation of lung surface area to apoptosis and proliferation in human emphysema. Eur Respir J 25: 250–258, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Johnston RA, Mizgerd JP, Flynt L, Quinton LJ, Williams ES, Shore SA. Type I interleukin-1 receptor is required for pulmonary responses to subacute ozone exposure in mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 37: 477–484, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kasahara Y, Tuder RM, Cool CD, Lynch DA, Flores SC, Voelkel NF. Endothelial cell death and decreased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 in emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 163: 737–744, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kirichenko A, Li L, Morandi MT, Holian A. 4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal-protein adducts and apoptosis in murine lung cells after acute ozone exposure. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 141: 416–424, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kosmider B, Loader JE, Murphy RC, Mason RJ. Apoptosis induced by ozone and oxysterols in human alveolar epithelial cells. Free Radic Biol Med 48: 1513–1524, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Koto H, Salmon M, Haddad el B, Huang TJ, Zagorski J, Chung KF. Role of cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant (CINC) in ozone-induced airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 156: 234–239, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kranenburg AR, Willems-Widyastuti A, Moori WJ, Sterk PJ, Alagappan VK, de Boer WI, Sharma HS. Enhanced bronchial expression of extracellular matrix proteins in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Clin Pathol 126: 725–735, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lappalainen U, Whitsett JA, Wert SE, Tichelaar JW, Bry K. Interleukin-1beta causes pulmonary inflammation, emphysema, and airway remodeling in the adult murine lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 32: 311–318, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Maestrelli P, Paska C, Saetta M, Turato G, Nowicki Y, Monti S, Formichi B, Miniati M, Fabbri LM. Decreased haem oxygenase-1 and increased inducible nitric oxide synthase in the lung of severe COPD patients. Eur Respir J 21: 971–976, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. March TH, Barr EB, Finch GL, Hahn FF, Hobbs CH, Menache MG, Nikula KJ. Cigarette smoke exposure produces more evidence of emphysema in B6C3F1 mice than in F344 rats. Toxicol Sci 51: 289–299, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. March TH, Barr EB, Finch GL, Nikula KJ, Seagrave JC. Effects of concurrent ozone exposure on the pathogenesis of cigarette smoke-induced emphysema in B6C3F1 mice. Inhal Toxicol 14: 1187–1213, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pauwels RA, Buist AS, Calverley PM, Jenkins CR, Hurd SS. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. NHLBI/WHO Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) Workshop summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 163: 1256–1276, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pendino KJ, Shuler RL, Laskin JD, Laskin DL. Enhanced production of linterleukin-1, tumor necrosis factor-α, and fibronectin by rat lung phagocytes following inhalation of a pulmonary irritant. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 11: 279–286, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pickrell JA, Gregory RE, Cole DJ, Hahn FF, Henderson RF. Effect of acute ozone exposure on the proteinase-antiproteinase balance in the rat lung. Exp Mol Pathol 46: 168–179, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pryor WA, Squadrito GL, Friedman M. The cascade mechanism to explain ozone toxicity: the role of lipid ozonation products. Free Radic Biol Med 19: 935–941, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rangasamy T, Cho CY, Thimmulappa RK, Zhen L, Srisuma SS, Kensler TW, Yamamoto M, Petrache I, Tuder RM, Biswal S. Genetic ablation of Nrf2 enhances susceptibility to cigarette smoke-induced emphysema in mice. J Clin Invest 114: 1248–1259, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rangasamy T, Misra V, Zhen L, Tankersley CG, Tuder RM, Biswal S. Cigarette smoke-induced emphysema in A/J mice is associated with pulmonary oxidative stress, apoptosis of lung cells, and global alterations in gene expression. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 296: L888–L900, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Segura-Valdez L, Pardo A, Gaxiola M, Uhal BD, Becerril C, Selman M. Upregulation of gelatinases A and B, collagenases 1 and 2, and increased parenchymal cell death in COPD. Chest 117: 684–694, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Seltzer J, Bigby BG, Stulborg M, Holtzman MJ, Nadel JA. O3-induced charge in bronchial reactivity to methacholine and airway inflammation in humans. J Appl Physiol 60: 1321–1326, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shapiro SD. Transgenic and gene-targeted mice as models for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J 29: 375–378, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Taraseviciene-Stewart L, Voelkel NF. Molecular pathogenesis of emphysema. J Clin Invest 118: 394–402, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Voynow JA, Fischer BM, Zheng S, Potts EN, Grover AR, Jaiswal AK, Ghio AJ, Foster WM. NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase 1 is essential for ozone-induced oxidative stress in mice and humans. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 41: 107–113, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 50. Wang Z, Zheng T, Zhu Z, Homer RJ, Riese RJ, Chapman HA, Jr, Shapiro SD, Elias JA. Interferon gamma induction of pulmonary emphysema in the adult murine lung. J Exp Med 192: 1587–1600, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Williams AS, Issa R, Durham A, Leung SY, Kapoun A, Medicherla S, Higgins LS, Adcock IM, Chung KF. Role of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in ozone-induced airway hyperresponsiveness and inflammation. Eur J Pharmacol 600: 117–122, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Williams AS, Leung SY, Nath P, Khorasani NM, Bhavsar P, Issa R, Mitchell JA, Adcock IM, Chung KF. Role of TLR2, TLR4, and MyD88 in murine ozone-induced airway hyperresponsiveness and neutrophilia. J Appl Physiol 103: 1189–1195, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Williams AS, Nath P, Leung SY, Khorasani N, McKenzie AN, Adcock IM, Chung KF. Modulation of ozone-induced airway hyperresponsiveness and inflammation by interleukin-13. Eur Respir J 32: 571–578, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yokohori N, Aoshiba K, Nagai A. Increased levels of cell death and proliferation in alveolar wall cells in patients with pulmonary emphysema. Chest 125: 626–632, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zheng T, Zhu Z, Wang Z, Homer RJ, Ma B, Riese RJ, Chapman HA, Shapiro SD, Elias JA. Inducible targeting of IL-13 to the adult lung causes matrix metalloproteinase- and cathepsin-dependent emphysema. J Clin Invest 106: 1081–1093, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]