Abstract

Urinary flow is not constant but in fact highly variable, altering the mechanical forces (shear stress, stretch, and pressure) exerted on the epithelial cells of the nephron as well as solute delivery. Nitric oxide (NO) and superoxide (O2−) play important roles in various processes within the kidney. Reductions in NO and increases in O2− lead to abnormal NaCl and water absorption and hypertension. In the last few years, luminal flow has been shown to be a regulator of NO and O2− production along the nephron. Increases in luminal flow enhance fluid, Na, and bicarbonate transport in the proximal tubule. However, we know of no reports directly addressing flow regulation of NO and O2− in this segment. In the thick ascending limb, flow-stimulated NO and O2− formation has been extensively studied. Luminal flow stimulates NO production by nitric oxide synthase type 3 and its translocation to the apical membrane in medullary thick ascending limbs. These effects are mediated by flow-induced shear stress. In contrast, flow-induced stretch and NaCl delivery stimulate O2− production by NADPH oxidase in this segment. The interaction between flow-induced NO and O2− is complex and involves more than one simply scavenging the other. Flow-induced NO prevents flow from increasing O2− production via cGMP-dependent protein kinase in thick ascending limbs. In macula densa cells, shear stress increases NO production and this requires that the primary cilia be intact. The role of luminal flow in NO and O2− production in the distal tubule is not known. In cultured inner medullary collecting duct cells, shear stress enhances nitrite accumulation, a measure of NO production. Although much progress has been made on this subject in the last few years, there are still many unanswered questions.

Keywords: stretch, pressure, shear stress, ion delivery, reactive oxygen species, oxidative stress

flow of the forming urine through the nephron is highly variable (11, 69). Flow changes as the result of 1) variations in glomerular filtration rate (37, 79); 2) tubuloglomerular feedback (28); 3) connecting tubule glomerular feedback (77); and 4) fluid absorption along the nephron (37, 80). In addition, mechanical constriction of the renal pelvis can halt and even reverse flow in deep nephrons (11). Acutely, tubuloglomerular feedback and renal pelvic peristalsis likely account for the largest changes in flow (11, 28). Chronically, variations in urinary flow can be caused by a high-salt (47) or high-protein diet (70), hypertension (4, 10), or early stages of diabetes (59). Flow may also be enhanced by diuretics such as acetazolamide and furosemide and could be modulated or even halted by obstruction of the urinary tract. Variations in luminal flow alter the mechanical forces that affect the epithelial cells forming the nephron, i.e., shear stress, transmural pressure and stretch, as well as solute delivery. Whether these parameters increase simultaneously or vary in opposing ways depends on what is altering flow.

Nitric oxide (NO) is a gaseous free radical produced by nitric oxide synthases (NOS), a family of enzymes that catalyze conversion of l-arginine to citrulline (5). Not counting splice variants, there are three NOS isoforms coded by separate genes: NOS 1, 2, and 3, formerly known as neuronal, inducible, and endothelial NOS (2). The earliest report that NO production could be regulated by flow came from the vascular literature and showed that elevated shear stress augmented NO production by NOS 3 (13, 15). This finding combined with reports that NO donors inhibited nephron transport (52, 58, 75) led to studies investigating, first, whether epithelial cells express any of the NOS isoforms, and, second, whether they can be activated by increased luminal flow.

Like NO, superoxide (O2−) is a free radical and the first reports that its production could be regulated by flow came from the vascular literature, showing that stretch of both endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells caused by increased flow stimulated O2− production by a family of enzymes known as nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidases (3). O2− can also be generated as a byproduct of reactions catalyzed by xanthine oxidase (56), P-450 monooxygenase (14), and other enzymes (35). Superoxide can also be generated by uncoupled NOS (21, 39). However, only NADPH oxidases appear to be regulated by parameters that can be altered by luminal flow (22, 26). In the nephron, interest in flow-regulated O2− production was initiated by reports showing that O2− helped control Na and water excretion, and therefore blood pressure (46, 51).

As stated above, in the last two decades both NO and O2− were implicated in Na and water homeostasis along the nephron. Reductions of NO and increases in O2− were postulated to play a role in the development of salt-sensitive hypertension and renal damage, and among other factors it has been proposed that luminal flow could regulate these two suggested opposed systems. Therefore, the role of flow-induced regulation of NO and O2− is of special significance especially when one of the systems predominates over the other.

Here, we will review the recent literature concerning flow-induced changes in NO and O2− production along the nephron.

Proximal Tubule

Changes in luminal flow in the proximal tubule result from changes in glomerular filtration rate or proximal nephron fluid absorption. While the effect of varying luminal flow in this segment on NO production in isolated tubules has not been studied to our knowledge, indirect data indicate that luminal flow would likely enhance NO production. Proximal tubules express all three NOS isoforms (71). Shear stress has been shown to activate NOS 3 and NOS 1 in other segments (7, 81), while reductions in intracellular pH caused by increased Na/H exchange activity stimulate NO production by NOS 1 in the macula densa (40). However, the most direct data come from studies involving activation of NOS 2. Elevation of pressure per se such as that caused by increased luminal flow enhances NO production by NOS 2 in cultured proximal tubular epithelial cells, possibly due to augmented NOS 2 expression (6). The significance of this finding comes from the spontaneously hypertensive rat, whose proximal tubules express more NOS 2 than normotensive rats (36).

As with NO, we know of no direct data showing that changing luminal flow alters O2− production in the proximal tubule. However, there are arguments both for and against flow stimulating O2− production. On the one hand, proximal tubules express NADPH oxidase (17), and changes in solute reabsorption in this segment can cause depolarization of the membrane potential, which enhances O2− production in other segments (42). Furthermore, fluid, bicarbonate, and Cl absorption are dependent on delivery in a manner that cannot be entirely explained by changes in luminal concentration. On the other hand, flow may have little influence on O2− production by NADPH oxidase in this segment. Since the proximal nephron is one of the least compliant segments (68), stretch due to changes in flow, a key stimulus for O2− production in other cells (16), would most likely be minimal.

Thick Ascending Limb

Flow-regulated NO production was most studied in the thick ascending limb. Thick ascending limbs express all three NOS isoforms, but physiologically NO produced by NOS 3 appears to be the most important (55, 57). We first showed that adding physiological concentrations of l-arginine, the substrate for NOS, to the basolateral bath of isolated, perfused medullary thick ascending limbs inhibited NaCl reabsorption (49, 58). This effect was conserved in NOS 1- and NOS 2-deficient mice but not in NOS 3 knockouts. However, we have shown that l-arginine inhibits chloride transport in NOS 3-deficient mice if NOS 3 is restored by gene transfer (55). These findings indicate that NO produced by NOS 3 in thick ascending limbs is responsible for the inhibition of transport caused by l-arginine. Because NOS 3 is allosterically regulated, one can assume there is no activity without allosteric modification of the enzyme. Thus it is not clear from these data how adding l-arginine to the bath could activate the enzyme. Based on this, we questioned why l-arginine inhibited NaCl reabsorption in the isolated, perfused tubule.

One of the most potent stimuli for NOS 3 activation, and therefore NO production by endothelial cells, is luminal flow (13, 15, 23, 38). When stimulated, NOS 3 also changes its subcellular localization in endothelial cells (12, 19, 61). Thus we tested whether increasing flow would activate NOS 3 in the thick ascending limb and cause it to be redistributed within the cell. We found that increasing luminal flow augmented NO production by thick ascending limbs (53). In the absence of flow, NOS 3 was uniformly distributed throughout the cell; however, in the presence of flow ∼70% was found at the apical membrane (53). As with endothelial cells, flow-stimulated NO production and NOS 3 translocation to the apical membrane was mediated by 1) phosphatidylinositol 3-OH kinase (PI3-kinase) and phosphorylation at serine 1179 and 2) the chaperone protein heat shock protein 90 (HSP-90) (54).

Shear stress, cellular stretch, pressure, and ion delivery all increase when flow is enhanced. We have shown that shear stress mediates flow-induced NO production in isolated, perfused thick ascending limbs. NO production was increased to a similar extent by flow in the presence and absence of all ions, suggesting that flow-induced mechanical strain, not increased ion delivery, mediated this effect. Increasing flow in tubules with their distal ends open enhanced NO production whereas increasing diameter to the same extent in tubules with the distal end pinched closed did not. Moreover, increasing stretch while reducing shear stress and pressure lowered NO generation. Luminal flow did not increase NO in thick ascending limbs from mice lacking NOS 3. These data indicate that NOS 3-derived NO is stimulated by luminal flow and that NOS 1 and NOS 2 are not involved in flow-induced NO production in this segment. Taken together, these findings suggest that shear stress, not ion delivery, cellular stretch, or pressure, stimulates NO production in thick ascending limbs (7).

The steps between elevated shear stress and activation of PI3-kinase are unclear. Mechanotransduction by polycystin 1 and/or 2 and transient receptor potential vanilloid type 4 channels has been postulated to mediate the initial transduction step, resulting in release of ATP. ATP is known to stimulate NO production in this segment (72) and is released in response to flow (34). We have recently shown that flow-induced NO production is mediated by ATP release (8); however, we have no data supporting the other steps, nor do we know whether primary cilia are involved as they are in macula densa cells (81).

Like NO, O2− production is stimulated by flow in the thick ascending limb (1, 29). All studies thus far implicate both increased NaCl delivery (thereby stimulating transport) and alterations in physical parameters, although the details differ. Abe et al. (1) first showed that increasing luminal NaCl enhanced O2− production by perfused thick ascending limbs and that ouabain could block this effect. We later reported that perfusing tubules with a NaCl-free solution reduced flow-induced O2− by ∼50% and that furosemide, a Na-K-2Cl cotransporter (NKCC2) inhibitor, had a similar effect (29). In Abe's study, the stimulatory effect of increased flow on O2− was greater at 60 than it was at 149 mM Na. We found that flow per se could enhance O2− but did not test the NaCl dependency of this process. This increase was due to activation of one or more NADPH oxidases. These data indicate that NaCl delivery alone cannot account for flow-induced O2−.

Because we found that half of flow-induced O2− was due to mechanical strain, we studied which of the three factors (shear stress, pressure, or stretch) is/are responsible for the effect of flow. Increasing pressure and stretch in the absence of shear stress increased O2− production by roughly the same degree as when all three were increased. Increasing stretch while reducing shear stress and pressure enhanced O2− production. Taken together, these data suggest that cellular stretch rather than shear stress or pressure stimulates O2− production in thick ascending limbs (16).

The effects of both increased NaCl delivery and stretch were found to be mediated by PKC. PKC activity was increased by luminal flow, and a nonselective PKC inhibitor completely prevented the increase in flow-induced O2−. Ultimately, PKCα was found to mediate the effects of flow; when tubules were transduced so that they expressed dominant negative PKCα, flow no longer stimulated O2− production. Neither dominant negative PKCβ1 nor -β2 blocked flow-induced O2− (31). However, it is not clear how stretch and ion delivery activate PKC or how PKC enhances O2− production.

Given that NO and O2− can react to form ONOO−, one might well ask whether increasing luminal flow actually produces any net NO or O2−. It was first shown that NO appeared to be produced in excess of O2−. Scavenging O2− increased the amount of NO that could be measured, but only by ∼50% (50). Increasing luminal NaCl also decreased NO production, presumably by enhancing O2− production (1). Therefore, it was initially assumed that the reduction in NO caused by O2− was just due to simple scavenging and resultant production of ONOO− (32).

Since NO appeared to be produced in excess of O2−, the reverse issue was then addressed by increasing luminal flow in the presence and absence of l-arginine, the substrate for NOS, and measuring O2−. NO was found to decrease measurable O2− by 70–80% (30). This is particularly interesting because even though NO is in excess and NO reacts with O2− at a rate of 7 × 109 mol·l−1·s−1 (32), not all flow-induced O2− could be scavenged by flow-induced NO. These data were interpreted to indicate that either NO and O2− were formed in different compartments or that another process besides simple scavenging accounted for the decrease in O2−. It was also reported that in the presence of a soluble guanylate cyclase inhibitor, flow-induced NO only decreased O2− by ∼36% (30). Dibutyryl cGMP, a cell-permeant form of cGMP, could mimic the reduction in O2− caused by NO. Additionally, in the presence of an inhibitor of cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG), the effect of flow-induced NO on flow-induced O2− was prevented. These findings indicate that flow-induced NO prevents flow from stimulating O2− generation primarily via a cGMP/PKG-dependent pathway, and only a small part of this reduction is due to scavenging by NO or some other process. However, the mechanisms by which cGMP and PKG prevent the increase in O2− caused by flow are unknown. Furthermore, while not directly tested, these results seem to indicate that NO and O2− are formed in different compartments and that NO does not diffuse freely throughout the cell as originally assumed. Another possibility could be that the increase in O2− production was due to a mechanism called NOS uncoupling. In this process, factors such as lack of l-arginine and/or other cofactors can convert this enzyme from a NO-producing to an O2−-producing enzyme (21, 60). However, in the previous report flow-induced O2− production was completely prevented by the NADPH oxidase inhibitor apocynin, suggesting that all the measured O2− came solely from NADPH. Additionally, flow enhanced O2− production to the same extent in the presence or absence of the NOS inhibitor Nω-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME). These data suggest that O2− generation by uncoupled NOS was not involved (30).

NO has been shown to decrease NaCl absorption in the thick ascending limb via cGMP (49, 52) while O2− enhances it (51, 73). Thus, if luminal flow increased both NO and O2−, the likely outcome on NaCl absorption would be minimal. However, when luminal flow is elevated acutely, flow-induced NO prevents the increase in O2− that would normally occur in the presence of flow (24, 30). This is due to a cGMP/PKG-dependent mechanism that inhibits O2− production by NADPH oxidase. It is not primarily due to simple scavenging of O2− by NO, although scavenging and the subsequent formation of ONOO− accounts for ∼20% of the reduction in O2− (30).

The chronic situation may be much different. ONOO− inhibits NOS 3 expression in the thick ascending limb (62). Thus one could speculate that if flow were to be elevated chronically as may occur in diabetes or a continuous high-salt diet, that formation of ONOO− would eventually reduce NOS 3 expression and NO production. This would begin a vicious cycle in which NO decreases and O2− increases. Ultimately, instead of flow leading to an increase in urinary NaCl excretion as it would in the acute setting, in the chronic situation elevated flow would lead to diminished NO, elevated O2−, and thus a decrease in NaCl excretion. This could contribute to increases in blood pressure and renal damage. There is some evidence for this as a high-salt diet first increases NO production and NOS 3 expression in the thick ascending limb but more chronically reduces both (25).

Macula Densa

The first data showing that luminal flow could regulate macula densa NO production came from micropuncture experiments; the loop of Henle (including the macula densa) was perfused at varying flow rates, and stop-flow pressure, a measure of tubuloglomerular feedback, was measured in the presence and absence of NOS inhibitors. Initially, nonselective NOS inhibitors were used, but eventually selective NOS 1 inhibitors were employed because the macula densa only expresses NOS 1. Essentially, all of these studies showed that inhibition of NOS 1 had no effect on stop-flow pressure when the macula densa was perfused at low flow rates; however, it enhanced the reduction in stop-flow pressure caused by perfusing the macula densa at higher flow rates (76). While these data were indirect, they were taken to indicate that some aspect of increasing luminal flow activated NOS 1. The first parameter tested was NaCl delivery, because tubuloglomerular feedback could be elicited by increasing NaCl delivery to the macula densa without changing the flow rate using an isolated, perfused juxtaglomerular apparatus preparation. NO production was found to increase when the NaCl concentration of the perfusate was increased but flow was held constant, suggesting that NaCl delivery activated NOS 1 in the macula densa (33, 66). It has been shown that NOS 1 is activated at an alkaline pH (20). Further experiments showed that increased NaCl concentration activated luminal Na/H exchanger 3, raising intracellular pH, and this in turn activated NOS 1 (40).

The fact that NO production could be enhanced by increased NaCl delivery did not rule out the possibility that changes in shear stress, pressure, or stretch also activate NOS 1 in the macula densa. Liu et al. (81) found that increasing shear stress stimulated NO production in an immortalized macula densa cell line (MMDD1) and that this effect was blunted by removing the primary cilia using an small interfering (si) RNA against polaris, a protein involved in normal ciliary development. In isolated, perfused juxtaglomerular apparatus preparations, increasing tubular flow enhanced NO production, and this effect was not dependent on NKCC2 activity. Taken together, these data suggest that flow-induced shear stress can stimulate NO production independently of NaCl delivery in the macula densa and that the primary cilia act as a mechanosensory organelle. Additional data showing that increasing the viscosity of the luminal perfusate were used by the authors to support their conclusion, but increasing viscosity in a tubular structure increases not only shear stress but also transmural pressure and thus stretch of the epithelial cells. Thus these data cannot be used to support the conclusion that shear stress mediated the effects of flow on NO production.

As with NO, the first data indicating that O2− production by the macula densa is flow dependent came from micropuncture experiments; here, an O2− scavenger did not affect stop-flow pressure in the absence of luminal flow but blunted the tubuloglomerular feedback response at 40 nl/min (78). Also, as with NO, this effect was seen in in vitro experiments using an isolated, perfused juxtaglomerular apparatus in which flow was held constant but NaCl delivery was increased (44, 63). The effect appeared to be due to NaCl transport by NKCC2 and the resultant membrane depolarization and activation of NADPH oxidase, because it could be inhibited by apocynin (42). Further experiments showed that activation and translocation to the apical membrane of the GTPase Rac 1 were involved in this effect (43). The increase in intracellular pH that accompanies heightened NaCl delivery augmented this effect but by itself was not sufficient to activate NADPH oxidase (41).

Distal Convoluted Tubule

The apparent lack of published data concerning luminal flow and either NO or O2− production in the distal convoluted tubule is unfortunate, as such data are crucial to our understanding of how changes in luminal flow alter urinary volume and Na excretion. This needs to be the focus of future experiments.

Connecting Tubule

Although we know of no direct data addressing whether luminal flow enhances NO or O2− production in the connecting tubule, there are indirect data showing that the increases in NaCl delivery that would accompany an increase in flow can stimulate NO production. In in vitro experiments where the connecting tubule is perfused and afferent arteriolar diameter measured, increasing NaCl delivery to the connecting tubule increased arteriolar diameter via a process known as connecting tubule glomerular feedback (CTGF) (65). Ren et al. (64) found that in the absence of NaCl delivery, perfusing the connecting tubule with a nonselective NOS inhibitor did not alter arteriolar diameter but did significantly enhance the CTGF response caused by increasing NaCl delivery to the connecting tubule. They interpreted these data as indicating that NO production is low with low NaCl delivery and increases when NaCl delivery is enhanced and that the NO produced in this way inhibits Na absorption by the connecting tubule. We know of no reports supporting a role for luminal flow and/or O2− in the connecting tubule.

Collecting Duct

The theory that luminal flow could alter NO production by the epithelial cells of the nephron was first put forward by Pollock and collaborators (9), who studied cultured inner medullary collecting duct cells (IMCD 3). They reported that nitrite content of the media, a measure of NO production, increased proportionately with shear stress (9). However, NO production in response to increases in luminal flow was not measured in isolated, perfused inner medullary collecting ducts; moreover, the source of NO was assumed to be NOS 3 but was not actually identified. Subsequent data indicated that the source of most NO produced by inner medullary collecting ducts is NOS 1 (48, 67), raising the possibility that NOS 1 can be activated by shear stress in this segment as it is in the macula densa (81). Although we could find no data addressing the signaling cascade activated by shear stress, it may involve ATP just as it does in the thick ascending limb (8). Sipos et al. (74) showed that increasing luminal flow in isolated, perfused cortical collecting ducts enhanced ATP release, which stimulates NO production in other cells (18, 72). Very recently, Lyon-Roberts et al. (45) showed that shear stress applied to IMCD cells stimulated endothelin-1 mRNA accumulation. Even though shear stress also stimulates NO production in IMCD cells, NO does not play a role in shear stress-induced endothelin-1 mRNA accumulation because this effect could not be prevented by the NOS inhibitor l-NAME.

We could find no reports supporting a role for luminal flow as a regulator of O2− in collecting ducts.

Summary

Luminal flow and its effects on NaCl delivery, shear stress, transmural pressure, and stretch of epithelial cells are now recognized as potential regulators of both NO and O2− production along the nephron.

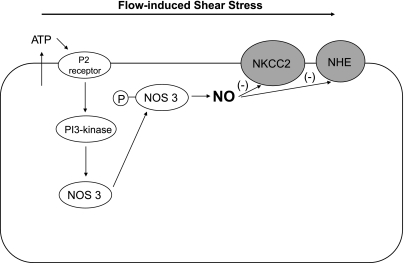

NO production is enhanced by elevations of pressure per se in cultured proximal tubular epithelial cells possibly due to augmented NOS 2 expression (6). In the thick ascending limb, luminal flow stimulates NO production by NOS 3 (7) and enhances NOS 3 activation and translocation to the apical membrane (53). This effect is mediated by PI3-kinase and the chaperone protein HSP-90 (54). Flow-induced shear stress rather than stretch, pressure, or ion delivery induces NO production via release of ATP in this segment (7, 8) (Fig. 1). In the macula densa, NaCl delivery via increases in intracellular pH stimulates NO production by NOS 1 (40). Shear stress also stimulates NO generation by NOS 1, and this effect requires an intact primary cilium (81). The role of luminal flow on NO regulation in the distal tubule is not known yet. In the connecting tubule, only indirect data indicate that NaCl delivery stimulates NO production (64). In IMCD cells, shear stress enhances NO nitrite production, suggesting that luminal flow regulates NO production in the collecting duct (9) (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Suggested mechanism of flow-induced shear stress on nitric oxide (NO) production in the thick ascending limb. Flow-induced shear stress stimulates NO production via ATP release and the subsequent activation of purinergic P2 receptors presumably by causing nitric oxide synthase 3 (NOS 3) activation and translocation to the apical membrane via phosphatidylinositol 3-OH kinase (PI3-kinase). Hypothetically, flow-induced NO production decreases NaCl transport by inhibiting Na-K-2Cl cotransporter (NKCC2) and Na/H exchanger (NHE) activity.

Table 1.

Regulation of nitric oxide along the nephron by flow-induced changes in shear stress, stretch, pressure, and/or NaCl delivery

| Shear Stress | Stretch | Pressure | NaCl Delivery | Reference(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proximal tubule | ? | ? | + (NOS 2) | ? | 6 |

| Thick ascending limb | + (NOS 3) | − | − | − | 7 |

| Macula densa | + (NOS 1) | ? | ? | + (NOS 1) | 40, 81 |

| Distal tubule | ? | ? | ? | ? | |

| Connecting tubule | ? | ? | ? | + | 64 |

| Collecting duct | + | ? | ? | ? | 9 |

NOS, nitric oxide synthase; +, stimulation; −, no effect; ?, unknown. The source of nitric oxide is indicated in each case.

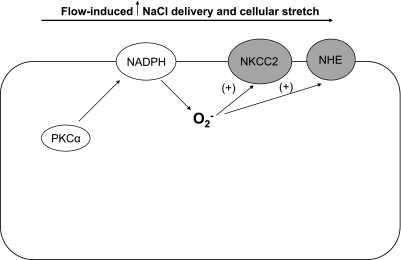

Flow-induced NaCl delivery and cellular stretch stimulate O2− production by NADPH oxidase in the thick ascending limb (1, 16, 29). This effect is mediated by activation of PKCα (31) (Fig. 2). Furthermore, flow-induced NO prevents flow-induced O2− generation mainly via a cGMP/PKG-dependent pathway (30). In the macula densa, only NaCl delivery has been shown to simulate O2− production (44, 63). To our knowledge, there are no data indicating yet a role for flow-induced regulation of O2− in the proximal tubule, distal tubule, connecting tubule, and collecting duct (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Suggested mechanism of flow-induced increases in NaCl delivery and cellular stretch on O2− production in the thick ascending limb. Flow-induced increases in NaCl delivery and cellular stretch stimulate O2− production by NADPH oxidase via PKCα activation. Hypothetically, flow-induced O2− production enhances NaCl transport by stimulating NKCC2 and NHE activity.

Table 2.

Regulation of superoxide along the nephron by flow-induced changes in shear stress, stretch, pressure, and/or NaCl delivery

| Shear Stress | Stretch | Pressure | NaCl Delivery | Reference(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proximal tubule | ? | ? | ? | ? | |

| Thick ascending limb | − | + (NADPH) | − | + (NADPH) | 1, 29, 16 |

| Macula densa | ? | ? | ? | + (NADPH) | 44, 63 |

| Distal tubule | ? | ? | ? | ? | |

| Connecting tubule | ? | ? | ? | ? | |

| Collecting duct | ? | ? | ? | ? |

The source of superoxide is indicated in each case.

Although a great advance has been made, this field is in its infancy and many fundamental questions remain to be answered, above all whether the in vitro data can be extrapolated to the in vivo situation. All of the data described above were collected using in vitro techniques, and it is not necessarily true that similar processes occur in vivo where numerous other factors besides luminal flow could alter both NO and O2− production. Moreover, while the effects of luminal flow on NO and O2− production were addressed assuming that flow is continuous, in fact it oscillates in vivo (27), and both the magnitude and frequency of these oscillations vary among species (11). Finally, not all nephron segments have been tested for flow dependence of NO and O2− production. Thus additional investigation is necessary both in vivo and in vitro.

GRANTS

This work was supported in part by grants to J .L. Garvin from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (HL 070985; HL 090550 and HL 028982).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abe M, O'connor P, Kaldunski M, Liang M, Roman RJ, Cowley AW., Jr Effect of sodium delivery on superoxide and nitric oxide in the medullary thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 291: F350–F357, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alderton WK, Cooper CE, Knowles RG. Nitric oxide synthases: structure, function and inhibition. Biochem J 357: 593–615, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Babior BM. NADPH oxidase: an update. Blood 93: 1464–1476, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baer PG, Bianchi G, Liliana D. Renal micropuncture study of normotensive and Milan hypertensive rats before and after development of hypertension. Kidney Int 13: 452–466, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bredt DS, Snyder SH. Nitric oxide: a physiologic messenger molecule. Annu Rev Biochem 63: 175–95, 175–195, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Broadbelt NV, Stahl PJ, Chen J, Mizrahi M, Lal A, Bozkurt A, Poppas DP, Felsen D. Early upregulation of iNOS mRNA expression and increase in NO metabolites in pressurized renal epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F1877–F1888, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cabral PD, Hong NJ, Garvin JL. Shear stress increases nitric oxide production in thick ascending limbs. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 299: F1185–F1192, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cabral PD, Garvin JL. ATP mediates flow-induced nitric oxide production in thick ascending limbs. FASEB J 24: 812, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cai Z, Xin J, Pollock DM, Pollock JS. Shear stress-mediated NO production in inner medullary collecting duct cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 279: F270–F274, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. DiBona GF, Rios LL. Mechanism of exaggerated diuresis in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol 235: 409–416, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dwyer TM, Schmidt-Nielsen B. The renal pelvis: machinery that concentrates urine in the papilla. News Physiol Sci 18: 1–6, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Feng Y, Venema VJ, Venema RC, Tsai N, Caldwell RB. VEGF induces nuclear translocation of Flk-1/KDR, endothelial nitric oxide synthase, and caveolin-1 in vascular endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 256: 192–197, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fisslthaler B, Dimmeler S, Hermann C, Busse R, Fleming I. Phosphorylation and activation of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase by fluid shear stress. Acta Physiol Scand 168: 81–88, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fulton D, McGiff JC, Wolin MS, Kaminski P, Quilley J. Evidence against a cytochrome P450-derived reactive oxygen species as the mediator of the nitric oxide-independent vasodilator effect of bradykinin in the perfused heart of the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 280: 702–709, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gallis B, Corthals GL, Goodlett DR, Ueba H, Kim F, Presnell SR, Figeys D, Harrison DG, Berk BC, Aebersold R, Corson MA. Identification of flow-dependent endothelial nitric-oxide synthase phosphorylation sites by mass spectrometry and regulation of phosphorylation and nitric oxide production by the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor LY294002. J Biol Chem 274: 30101–30108, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Garvin JL, Hong NJ. Cellular stretch increases superoxide production in the thick ascending limb. Hypertension 51: 488–493, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Geiszt M, Kopp JB, Varnai P, Leto TL. Identification of renox, an NAD(P)H oxidase in kidney. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 8010–8014, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gendron FP, Chalimoniuk M, Strosznajder J, Shen S, Gonzalez FA, Weisman GA, Sun GY. P2X7 nucleotide receptor activation enhances IFN gamma-induced type II nitric oxide synthase activity in BV-2 microglial cells. J Neurochem 87: 344–352, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Goetz RM, Thatte HS, Prabhakar P, Cho MR, Michel T, Golan DE. Estradiol induces the calcium-dependent translocation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 2788–2793, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gorren AC, Schrammel A, Schmidt K, Mayer B. Effects of pH on the structure and function of neuronal nitric oxide synthase. Biochem J 331: 801–807, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Govers R, Rabelink TJ. Cellular regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 280: F193–F206, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Grote K, Flach I, Luchtefeld M, Akin E, Holland SM, Drexler H, Schieffer B. Mechanical stretch enhances mRNA expression and proenzyme release of matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) via NAD(P)H oxidase-derived reactive oxygen species. Circ Res 92: e80–e86, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hecker M, Mulsch A, Bassenge E, Busse R. Vasoconstriction and increased flow: two principal mechanisms of shear stress-dependent endothelial autacoid release. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 265: H828–H833, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Herrera M, Hong NJ, Garvin J. Flow-induced NO suppresses flow-induced O2− in the thick ascending limb in vivo (Abstract). Hypertension 56: e50–e166, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Herrera M, Silva GB, Garvin JL. A high-salt diet dissociates NO synthase-3 expression and NO production by the thick ascending limb. Hypertension 47: 95–101, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hishikawa K, Luscher TF. Pulsatile stretch stimulates superoxide production in human aortic endothelial cells. Circulation 96: 3610–3616, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Holstein-Rathlou NH, Marsh DJ. Oscillations of tubular pressure, flow, and distal chloride concentration in rats. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 256: F1007–F1014, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Holstein-Rathlou NH, Marsh DJ. A dynamic model of the tubuloglomerular feedback mechanism. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 258: F1448–F1459, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hong NJ, Garvin JL. Flow increases superoxide production by NADPH oxidase via activation of Na-K-2Cl cotransport and mechanical stress in thick ascending limbs. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F993–F998, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hong NJ, Garvin JL. Nitric oxide reduces flow-induced superoxide production via cGMP-dependent protein kinase in thick ascending limbs. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 296: F1061–F1066, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hong NJ, Silva GB, Garvin JL. PKC-α mediates flow-stimulated superoxide production in thick ascending limbs. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298: F885–F891, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Huie RE, Padmaja S. The reaction of no with superoxide. Free Radic Res Commun 18: 195–199, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ito S, Ren Y. Evidence for the role of nitric oxide in macula densa control of glomerular hemodynamics. J Clin Invest 92: 1093–1098, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jensen ME, Odgaard E, Christensen MH, Praetorius HA, Leipziger J. Flow-induced [Ca2+]i increase depends on nucleotide release and subsequent purinergic signaling in the intact nephron. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2062–2070, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kontos HA, Wei EP, Ellis EF, Jenkins LW, Povlishock JT, Rowe GT, Hess ML. Appearance of superoxide anion radical in cerebral extracellular space during increased prostaglandin synthesis in cats. Circ Res 57: 142–151, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kumar U, Chen J, Sapoznikhov V, Canteros G, White BH, Sidhu A. Overexpression of inducible nitric oxide synthase in the kidney of the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Clin Exp Hypertens 27: 17–31, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Leyssac PP, Karlsen FM, Holstein-Rathlou NH, Skøtt O. On determinants of glomerular filtration rate after inhibition of proximal tubular reabsorption. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 266: R1544–R1550, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Li Y, Zheng J, Bird IM, Magness RR. Effects of pulsatile shear stress on nitric oxide production and endothelial cell nitric oxide synthase expression by ovine fetoplacental artery endothelial cells. Biol Reprod 69: 1053–1059, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lin MI, Fulton D, Babbitt R, Fleming I, Busse R, Pritchard KA, Jr, Sessa WC. Phosphorylation of threonine 497 in endothelial nitric-oxide synthase coordinates the coupling of l-arginine metabolism to efficient nitric oxide production. J Biol Chem 278: 44719–44726, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Liu R, Carretero OA, Ren Y, Garvin JL. Increased intracellular pH at the macula densa activates nNOS during tubuloglomerular feedback. Kidney Int 67: 1837–1843, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Liu R, Carretero OA, Ren Y, Wang H, Garvin JL. Intracellular pH regulates superoxide production by the macula densa. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F851–F856, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Liu R, Garvin JL, Ren Y, Pagano PJ, Carretero OA. Depolarization of the macula densa induces superoxide production via NAD(P)H oxidase. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F1867–F1872, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Liu R, Juncos LA. GTPase-Rac enhances depolarization-induced superoxide production by the macula densa during tubuloglomerular feedback. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 298: R453–R458, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Liu R, Ren Y, Garvin JL, Carretero OA. Superoxide enhances tubuloglomerular feedback by constricting the afferent arteriole. Kidney Int 66: 268–274, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lyon-Roberts B, Strait KA, van Peursem E, Kittikulsuth W, Pollock JS, Pollock DM, Kohan DE. Flow regulation of collecting duct endothelin-1 production. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 300: F650–F666, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Majid DS, Nishiyama A. Nitric oxide blockade enhances renal responses to superoxide dismutase inhibition in dogs. Hypertension 39: 293–297, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mozaffari MS, Jirakulsomchok S, Shao ZH, Wyss JM. High-NaCl diets increase natriuretic and diuretic responses in salt-resistant but not salt-sensitive SHR. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 260: F890–F897, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nakano D, Pollock JS, Pollock DM. Renal medullary ETB receptors produce diuresis and natriuresis via NOS1. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294: F1205–F1211, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ortiz PA, Garvin JL. NO inhibits NaCl absorption by rat thick ascending limb through activation of cGMP-stimulated phosphodiesterase. Hypertension 37: 467–471, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ortiz PA, Garvin JL. Interaction of O2− and NO in the thick ascending limb. Hypertension 39: 591–596, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ortiz PA, Garvin JL. Superoxide stimulates NaCl absorption by the thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 283: F957–F962, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ortiz PA, Hong NJ, Garvin JL. NO decreases thick ascending limb chloride absorption by reducing Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter activity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 281: F819–F825, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ortiz PA, Hong NJ, Garvin JL. Luminal flow induces eNOS activation and translocation in the rat thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 287: F274–F280, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ortiz PA, Hong NJ, Garvin JL. Luminal flow induces eNOS activation and translocation in the rat thick ascending limb. II. Role of PI3-kinase and Hsp90. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 287: F281–F288, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ortiz PA, Hong NJ, Wang D, Garvin JL. Gene transfer of eNOS to the thick ascending limb of eNOS-KO mice restores the effects of l-arginine on NaCl absorption. Hypertension 42: 674–679, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Parks DA, Granger DN. Xanthine oxidase: biochemistry, distribution and physiology. Acta Physiol Scand Suppl 548: 87–99, 1986 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Plato CF, Shesely EG, Garvin JL. eNOS mediates l-arginine-induced inhibition of thick ascending limb chloride flux. Hypertension 35: 319–323, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Plato CF, Stoos BA, Wang D, Garvin JL. Endogenous nitric oxide inhibits chloride transport in the thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 276: F159–F163, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Pollock CA, Lawrence JR, Field MJ. Tubular sodium handling and tubuloglomerular feedback in experimental diabetes mellitus. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 260: F946–F952, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Pou S, Keaton L, Surichamorn W, Rosen GM. Mechanism of superoxide generation by neuronal nitric-oxide synthase. J Biol Chem 274: 9573–9580, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Prabhakar P, Thatte HS, Goetz RM, Cho MR, Golan DE, Michel T. Receptor-regulated translocation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase. J Biol Chem 273: 27383–27388, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ramseyer V, Garvin JL. Angiotensin II decreases NOS3 expression via nitric oxide and superoxide in the thick ascending limb. Hypertension 53: 313–318, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ren Y, Carretero OA, Garvin JL. Mechanism by which superoxide potentiates tubuloglomerular feedback. Hypertension 39: 624–628, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ren Y, Garvin JL, Liu R, Carretero OA. Crosstalk between the connecting tubule and the afferent arteriole regulates renal microcirculation. Kidney Int 71: 1116–1121, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ren Y, Garvin JL, Liu R, Carretero OA. Cross-talk between arterioles and tubules in the kidney. Pediatr Nephrol 24: 31–35, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ren YL, Garvin JL, Carretero OA. Role of macula densa nitric oxide and cGMP in the regulation of tubuloglomerular feedback. Kidney Int 58: 2053–2060, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Roczniak A, Zimpelmann J, Burns KD. Effect of dietary salt on neuronal nitric oxide synthase in the inner medullary collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 275: F46–F54, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Sakai T, Craig DA, Wexler AS, Marsh DJ. Fluid waves in renal tubules. Biophys J 50: 805–813, 1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Schmidt-Nielsen B. The renal concentrating mechanism in insects and mammals: a new hypothesis involving hydrostatic pressures. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 268: R1087–R1100, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Seney FD, Jr, Persson EG, Wright FS. Modification of tubuloglomerular feedback signal by dietary protein. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 252: F83–F90, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Shin SJ, Lai FJ, Wen JD, Lin SR, Hsieh MC, Hsiao PJ, Tsai JH. Increased nitric oxide synthase mRNA expression in the renal medulla of water-deprived rats. Kidney Int 56: 2191–2202, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Silva GB, Beierwaltes WH, Garvin JL. Extracellular ATP stimulates NO production in rat thick ascending limb. Hypertension 47: 563–567, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Silva GB, Ortiz PA, Hong NJ, Garvin JL. Superoxide stimulates NaCl absorption in the thick ascending limb via activation of protein kinase C. Hypertension 48: 467–472, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Sipos A, Vargas SL, Toma I, Hanner F, Willecke K, Peti-Peterdi J. Connexin 30 deficiency impairs renal tubular ATP release and pressure natriuresis. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 1724–1732, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Stoos BA, Garcia NH, Garvin JL. Nitric oxide inhibits sodium reabsorption in the isolated perfused cortical collecting duct. J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 89–94, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Thorup C, Erik A, Persson G. Macula densa derived nitric oxide in regulation of glomerular capillary pressure. Kidney Int 49: 430–436, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Wang H, Garvin JL, D'Ambrosio MA, Ren Y, Carretero OA. Connecting tubule glomerular feedback antagonizes tubuloglomerular feedback in vivo. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 299: F1374–F1378, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Welch WJ, Tojo A, Wilcox CS. Roles of NO and oxygen radicals in tubuloglomerular feedback in SHR. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 278: F769–F776, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Yip KP, Holstein-Rathlou NH, Marsh DJ. Mechanisms of temporal variation in single-nephron blood flow in rats. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 264: F427–F434, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Zhang Y, Mircheff AK, Hensley CB, Magyar CE, Warnock DG, Chambrey R, Yip KP, Marsh DJ, Holstein-Rathlou NH, McDonough AA. Rapid redistribution and inhibition of renal sodium transporters during acute pressure natriuresis. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 270: F1004–F1014, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Zhu X, Lu D, Fu Y, Liu H, Lu Y, Juncos LA, Liu R. Shear stress at the macula densa blunts tubuloglomerular feedback via primary cilia-dependent increases in MD nNOS activity (Abstract). Hypertension 56: e50–e166 2010 [Google Scholar]