Abstract

Acetylcholine regulates perfusion of numerous organs via changes in local blood flow involving muscarinic receptor-induced release of vasorelaxing agents from the endothelium. The purpose of the present study was to determine the role of M1, M3, and M5 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in vasodilation of small arteries using gene-targeted mice deficient in either of the three receptor subtypes (M1R−/−, M3R−/−, or M5R−/− mice, respectively). Muscarinic receptor gene expression was determined in murine cutaneous, skeletal muscle, and renal interlobar arteries using real-time PCR. Moreover, respective arteries from M1R−/−, M3R−/−, M5R−/−, and wild-type mice were isolated, cannulated with micropipettes, and pressurized. Luminal diameter was measured using video microscopy. mRNA for all five muscarinic receptor subtypes was detected in all three vascular preparations from wild-type mice. However, M3 receptor mRNA was found to be most abundant. Acetylcholine produced dose-dependent dilation in all three vascular preparations from M1R−/−, M5R−/−, and wild-type mice. In contrast, cholinergic dilation was virtually abolished in arteries from M3R−/− mice. Deletion of either M1, M3, or M5 receptor genes did not affect responses to nonmuscarinic vasodilators, such as substance P and nitroprusside. These findings provide the first direct evidence that M3 receptors mediate cholinergic vasodilation in cutaneous, skeletal muscle, and renal interlobar arteries. In contrast, neither M1 nor M5 receptors appear to be involved in cholinergic responses of the three vascular preparations tested.

Keywords: muscarinic receptors, vasodilation, genetically altered mice

acetylcholine is a powerful dilator of most vascular beds and a major diagnostic and investigative tool for the assessment of endothelial function (15, 24, 42). Its activity is mediated by endothelial muscarinic receptors triggering the release of the actual vasorelaxing agents, such as nitric oxide (NO) (19, 26). Five muscarinic receptor subtypes, M1–M5, have been identified (9). They are generally grouped according to their preferential functional coupling, either to the mobilization of intracellular calcium via activation of phospholipase Cβ (M1, M3, M5) or to the inhibition of adenylyl cyclase (M2, M4) (45). The odd-numbered muscarinic receptor subtypes (M1, M3, and M5) have been reported to mediate endothelium-dependent vasodilation. Based on pharmacological studies making use of subtype-preferring agents, the M1 receptor was suggested to be involved in cholinergic vasorelaxation of rat carotid arteries, the perforating branch of the human internal mammary artery, and human pulmonary and canine lingual arteries (10, 29, 32, 36). Other classical pharmacological studies as well as functional studies in gene-targeted mice lacking specific muscarinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes demonstrated that the M3 receptor mediates cholinergic vasodilation in various conduit vessels, such as the aorta and the femoral artery, and in some resistance vessels, such as coronary and ophthalmic arteries (2–3, 16, 20, 25). One particularly striking observation was that the M5 receptor mediated cholinergic responses in cerebral vessels from humans, cattle, and mice (13, 46). Based on these findings, distinct muscarinic receptors may represent attractive therapeutic targets for the treatment of local ischemic disorders. Hence, it is important to clearly define the functional role of individual muscarinic receptor subtypes in the major vascular resistance beds considerably contributing to the systemic cardiovascular side effects, e.g., hypotension and flushing, encountered during the application of nonselective cholinergic agonists. Therefore, the goal of the present study was to examine the hypothesis that M1, M3, and M5 receptors contribute to acetylcholine-induced vasodilation in small arteries from different vascular beds.

Because conclusions regarding the physiological role of individual muscarinic receptor subtypes are limited by the low selectivity of pharmacological agonists and antagonists, we used M1, M3, and M5 receptor knockout mice (M1R−/−, M3R−/−, and M5R−/− mice, respectively) to perform functional studies in cutaneous, skeletal muscle, and renal interlobar arteries, all vessels from vascular beds substantially contributing to the control of systemic vascular resistance (18).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

The generation of M1R−/−, M3R−/−, and M5R−/− mice has been described previously (17, 46–47). Briefly, the M1, M3, or the M5 receptor gene was inactivated using mouse embryonic stem cells derived from 129SvEv mice. The resulting chimeric mice were then mated with CF-1 mice to generate M1R−/−, M3R−/−, M5R−/−, and wild-type mice with the following genetic contribution: 129SvEv (50%) × CF-1 (50%). In all experiments, male mice at the age of 4–6 mo were used. All animal procedures conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the United States National Institutes of Health (NIH publication no. 85–23, revised 1996) and were approved by the local government.

Real-time PCR analysis in isolated arteries.

Muscarinic receptor gene expression was quantified in isolated cutaneous, skeletal muscle, and renal interlobar arteries using real-time PCR. Mice were killed by CO2 inhalation. Next, the kidneys, the hindlimbs, and a proximal segment of the tail were immediately removed and placed in ice-cold PBS solution (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany). Small cutaneous arteries from the tail, arteries from the gracilis muscle, and renal interlobar arteries were carefully isolated by using fine-point tweezers under a dissecting microscope, transferred to a 1.5-ml tube, and immediately snap-frozen. Subsequently, vessels were homogenized in lysis buffer using a homogenizing device (T10 basic Ultra-Turrax; IKA, Staufen, Germany). After homogenization, total RNA was extracted with a kit (RNeasy Micro Kit; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol. After complete DNA digestion, the RNA was reverse transcribed with the use of an RT-PCR kit [High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (no. 4368814), RNase Inhibitor (no. N8080119); Applied Biosystems, Darmstadt, Germany] and random hexamers. Quantitative PCR analysis was performed (GeneAmp StepOne Plus; Applied Biosystems, Darmstadt, Germany). Nucleic acid stain (SYBR Green; Bioline, Luckenwalde, Germany) was used for the fluorescent detection of DNA generated during PCR. The PCR reaction was performed in a total volume of 12.5 μl with 0.4 pmol/μl of each primer and 2× ready-to-use master mix (ImmoMix, BIO-25020; Bioline); 2 μl cDNA were used as template. Published sequences for mouse M1 (NM_007698), M2 (NM_203491), M3 (NM_033269), M4 (NM_007699), and M5 (NM_205783) were used to design primers for PCR amplification. Primer sequences were M1 sense 5′-TGA CAG GCA ACC TGC TGG TGC T-3′ and antisense 5′-AAT CAT CAG AGC TGC CCT GCG G-3′; M2 sense 5′-CGG ACC ACA AAA ATG GCA GGC AT-3′and antisense 5′-CCA TCA CCA CCA GGC ATG TTG TTG T-3′; M3 sense 5′-CCT CTT GAA GTG CTG CGT TCT GAC C-3′ and antisense 5′-TGC CAG GAA GCC AGT CAA GAA TGC-3′; M4 sense 5′-TGT GGT GAG CAA TGC CTC TGT CAT G-3′ and antisense 5′-GGC TTC ATC AGA GGG CTC TTG AGG A-3′; M5 sense 5′-ACC ACT GAC ATA CCG AGC CAA GCG-3′ and antisense 5′-TTC CCG TTG TTG AGG TGC TTC TAC G-3′; β-actin sense 5′-CAC CCG CGA GCA CAG CTT CTT T-3′ and antisense 5′-AAT ACA GCC CGG GGA GCA TC-3′. The expression levels of muscarinic receptor subtype mRNA were normalized to β-actin using the ΔCt method. Parallelism of standard curves was confirmed.

Vessel preparation.

Mice were killed by CO2 inhalation. Next, the kidneys, the hindlimbs, and a proximal segment of the tail were immediately removed and placed in ice-cold Krebs buffer with the following ionic composition (in mmol/l): 118.3 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.2 KH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, and 11 glucose. Small cutaneous arteries from the tail (115–267 μm internal diameter), arteries from the gracilis muscle (64–138 μm internal diameter), and renal interlobar arteries (62–145 μm internal diameter) from M1R−/−, M3R−/−, M5R−/−, and wild-type mice were isolated under an operating microscope, placed in an organ chamber filled with cold Krebs buffer, cannulated on two glass micropipettes, and secured with 10–0 nylon monofilament suture as described previously (20, 46). Vessels were pressurized via the micropipettes to 60 mmHg under no-flow conditions using two reservoirs filled with Krebs buffer and imaged using a video camera mounted on an inverted microscope. Video sequences were captured on a personal computer for analysis. The organ chamber was continuously circulated with oxygenated and carbonated Krebs buffer at 37°C and pH 7.4, and arteries were allowed to equilibrate for 30–40 min before the start of experiments. Viability of vessels was assessed as satisfactory when at least 50% constriction from resting diameter in response to KCl (100 mmol/l) was achieved.

Protocols.

Arteries were preconstricted with the α1-adrenergic receptor agonist phenylephrine to 40–70% of the initial vessel diameter, and cumulative concentration-response curves to acetylcholine (10−9 to 10−4 mol/l; Sigma-Aldrich, Munich, Germany) and to substance P (10−12 to 10−9 mol/l; Biotrend, Cologne, Germany), a nonmuscarinic endothelium-dependent vasodilator, were obtained. Responses to acetylcholine (10−4 mol/l) were also compared before and after addition of atropine (10−5 mol/l; Sigma-Aldrich), a nonselective muscarinic receptor antagonist. Furthermore, responses to the acetylcholine analog carbachol (10−4 mol/l; Sigma-Aldrich) and to the endothelium-independent vasodilator sodium nitroprusside (10−5 mol/l; Sigma-Aldrich) were tested.

Statistical analysis.

Data are presented as means ± SE, and n represents the number of mice per group. Vascular responses are presented as a percentage of change in diameter from the preconstricted diameter. Comparisons among concentration-response curves were made using ANOVA for repeated measurements. One-way ANOVA was used for comparison of mRNA expression levels and to measure for statistical differences among vascular responses to carbachol and to nitroprusside obtained by a single dose application. Post hoc comparisons were performed by Bonferroni's test. For comparisons of vascular responses to acetylcholine before and after atropine treatment, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used. A value of P < 0.05 was defined as significant.

RESULTS

Muscarinic receptor mRNA expression.

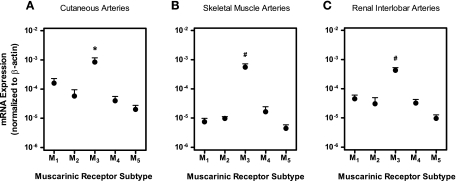

Using real-time PCR, we quantified mRNA expression of individual muscarinic receptor subtypes in cutaneous, skeletal muscle, and renal interlobar arteries from wild-type mice. In each preparation, mRNA for all five muscarinic receptor subtypes was detected. However, M3 receptor mRNA was found to be most abundant (Fig. 1). Deletion of the gene coding for the M1, M3, or M5 receptor only caused modest changes in the mRNA expression pattern of the remaining four muscarinic receptor subtypes [Supplemental Material (Supplemental data for this article may be found on the American Journal of Physiology: Heart and Circulatory Physiology website)].

Fig. 1.

Relative mRNA expression of individual muscarinic receptor subtypes (M1–M5) normalized to β-actin transcripts in cutaneous (A), skeletal muscle (B), and renal interlobar (C) arteries from wild-type mice. In each vascular bed, mRNA for all five muscarinic receptor subtypes was detected, but the highest expression levels were found for the M3 receptor. *P < 0.05, M3 receptor vs. all other subtypes. #P < 0.01, M3 receptor vs. all other subtypes (n = 5–7/artery group).

Vascular responses to cholinergic agents.

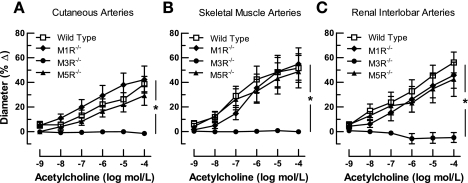

To test whether M1, M3, or M5 receptors are involved in cholinergic vasodilation of cutaneous, skeletal muscle, and renal interlobar arteries, we compared vascular responses of M1R−/−, M3R−/−, M5R−/−, and wild-type mice to acetylcholine (10−9 to 10−4 mol/l). Acetylcholine elicited dose-dependent dilation in all vascular preparations from M1R−/−, M5R−/−, and wild-type mice that was similar in the three groups (Fig. 2). In M3R−/− mice, however, acetylcholine-induced responses were virtually abolished in arteries from all three vascular regions tested (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Responses of cutaneous (A), skeletal muscle (B), and renal interlobar (C) arteries from wild-type and M1, M3, and M5 receptor knockout mice (M1R−/−, M3R−/−, and M5R−/− mice, respectively) to acetylcholine. Vasodilation to acetylcholine was negligible in all three preparations from M3R−/− mice, whereas deletion of the M1 or M5 receptor gene had no significant effect on acetylcholine-induced responses. *P < 0.05, M3R−/− vs. all other groups (n = 8–12/concentration and genotype).

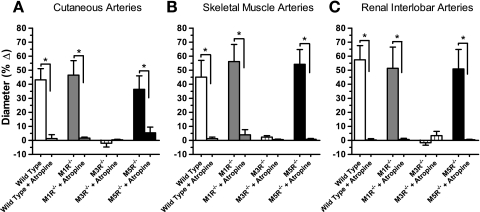

To examine whether cholinergic responses of arteries were mediated by muscarinic receptors, we tested responses to acetylcholine (10−4 mol/l) before and after addition of atropine (10−5 mol/l), a nonselective muscarinic receptor blocker. After atropine treatment, responses to acetylcholine were almost completely abolished in all vascular preparations (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Responses of cutaneous (A), skeletal muscle (B), and renal interlobar (C) arteries to acetylcholine (10−4 mol/l) were virtually abolished after incubation with atropine (10−5 mol/l). *P < 0.05 (n = 6–8/genotype).

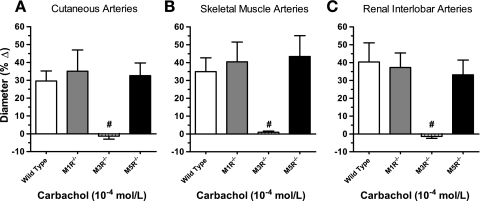

To exclude the possibility that different responses to acetylcholine were caused by differences in acetylcholinesterase activity in the vascular wall, we tested vascular responses to carbachol (10−4 mol/l), another muscarinic receptor agonist that, in contrast to acetylcholine, is resistant to degradation by acetylcholinesterase. Similar to acetylcholine, carbachol induced pronounced vasodilation in cutaneous, skeletal muscle, and renal interlobar arteries from M1R−/−, M5R−/−, and wild-type mice that did not differ between these three genotypes (Fig. 4). In contrast, vasodilation to carbachol was negligible in M3R−/− mice (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Responses of cutaneous (A), skeletal muscle (B), and renal interlobar arteries (C) from wild-type, M1R−/−, M3R−/−, and M5R−/− mice to carbachol (10−4 mol/l). Vasodilation to carbachol was negligible in all three preparations from M3R−/− mice, whereas deletion of the M1 or M5 receptor gene had no significant effect on carbachol-induced responses. #P < 0.01, M3R−/− vs. all other groups (n = 8–10/genotype).

Vascular responses to noncholinergic agents.

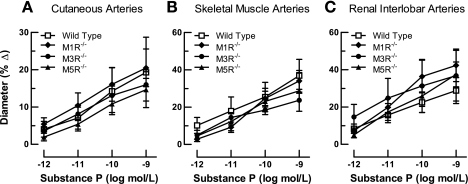

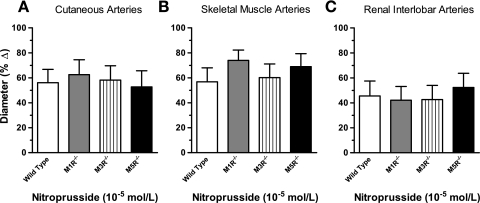

To examine whether deletion of the M1, M3, or M5 receptor genes affected vasodilation to a nonmuscarinic endothelium-dependent agonist, we examined responses of cutaneous, skeletal muscle, and renal interlobar arteries from M1R−/−, M3R−/−, M5R−/−, and wild-type mice to substance P (10−12 to 10−9 mol/l). Substance P elicited concentration-dependent dilatory responses in all three vascular preparations that did not differ between the four mouse genotypes (Fig. 5). Also, the endothelium-independent NO donor nitroprusside (10−5 mol/l) produced vasodilation in arteries from M1R−/−, M3R−/−, M5R−/−, and wild-type mice that did not differ between the four groups (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Responses of cutaneous (A), skeletal muscle (B), and renal interlobar (C) arteries from wild-type, M1R−/−, M3R−/−, and M5R−/− mice to substance P. Deletion of either the M1, M3, or the M5 receptor did not affect responses to this endothelium-dependent vasodilator (n = 7–9/concentration and genotype).

Fig. 6.

Responses of cutaneous (A), skeletal muscle (B), and renal interlobar (C) arteries from wild-type, M1R−/−, M3R−/−, and M5R−/− mice to nitroprusside (10−5 mol/l). Deletion of either the M1, M3, or the M5 receptor did not affect responses to nitroprusside (n = 8–11/genotype).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of the present study was to determine the functional role of M1, M3, and M5 acetylcholine receptor subtypes in cutaneous, skeletal muscle, and renal interlobar arteries, all arteries from vascular beds substantially contributing to the control of systemic vascular resistance. Because of the lack of muscarinic agonists and antagonists with pronounced subtype selectivity, we used gene-targeted mice deficient in each of the three receptor subtypes to study vascular function. Remarkably, deletion of the gene coding for the M3 receptor virtually abolished acetylcholine-induced vasodilation in arteries from all three vascular beds tested. In contrast, neither deletion of the M1 nor of the M5 receptor gene significantly affected cholinergic vasodilation. In M3R−/− mice, vasodilation of cutaneous, skeletal muscle, and renal interlobar arteries was also negligible in response to the acetylcholine analog carbachol, which is resistant to degradation by acetylcholinesterase. Thus differences in acetylcholinesterase activity in the vascular wall are not likely to contribute to the lack of cholinergic responsiveness of arteries from M3R−/− mice. In all three vascular preparations, responses to acetylcholine were almost completely abolished after treatment with the nonselective muscarinic receptor antagonist atropine, indicative of the predominant involvement of muscarinic receptors. Deletion of genes coding for either M1, M3, or M5 receptors did not affect vascular responses to the nonmuscarinic endothelium-dependent vasodilator substance P and to the endothelium-independent NO donor nitroprusside, suggesting that the absence of these receptors does not interfere with the downstream signaling cascades that ultimately mediate vasorelaxation.

Previous studies of mRNA expression revealed diverse distribution of muscarinic receptor subtypes among vascular beds (34). Moreover, it has been shown that not all muscarinic receptor subtypes expressed in a specific blood vessel contribute to vasodilation responses (20, 25). In the present study, we found mRNA for all five muscarinic receptor subtypes in cutaneous, skeletal muscle, and renal interlobar arteries from wild-type mice. Remarkably, in each vascular bed tested, the highest mRNA expression levels were found for the M3 receptor, in agreement with our findings in functional studies. Disruption of one specific muscarinic receptor gene had only modest effects on the expression pattern of the remaining four receptor subtypes, which is in line with previous studies in nonvascular tissues (44). Our findings also indicate a lack of functional compensation by other muscarinic receptor subtypes because responses to acetylcholine and carbachol were negligible in mice devoid of the M3 receptor.

Pharmacological studies making use of subtype-preferring agents as well as functional studies in vascular preparations from muscarinic receptor knockout mice have demonstrated that the M3 receptor is the predominant mediator of cholinergic vasodilation in coronary and ocular blood vessels (7, 20, 25, 30, 35, 48). Thus, from a clinical point of view, the M3 receptor may represent an attractive pharmacological target to modulate cardiac and ocular perfusion. However, before the potential clinical usefulness of this approach can be pursued further, it is important to define the functional role of individual muscarinic receptor subtypes in other vascular resistance beds. So far, only few studies have been performed analyzing muscarinic receptor function in vascular beds substantially contributing to total peripheral resistance. For example, in vivo studies in normo- and hypertensive humans employing receptor subtype-preferring antagonists suggested that cholinergic vasodilation in forearm resistance vessels is mainly mediated by M3 receptors (5–6). Similar results have been obtained in pharmacological studies in rat isolated perfused kidneys and in mesenteric vascular preparations from rats and mice (14, 21–23). Other classical pharmacological studies in the cat middle cerebral artery and in mouse pial arterioles also suggested that M3 receptors are responsible for cholinergic vasorelaxation in the cerebral circulation (11, 38). However, the findings in cerebral blood vessels have been challenged by more recent studies reporting that the pharmacological profile of the muscarinic receptor subtype mediating vasodilation in human and bovine cerebral arterioles corresponds best with the M5 subtype (13). In agreement with this finding, studies in M5 receptor-deficient mice demonstrated that responses to acetylcholine were almost completely abolished in pial arterioles and in the basilar artery (46). Similarly seemingly contradictory results have been reported in other vascular beds. For example, pharmacological experiments in dogs and sheep suggested that cholinergic vasorelaxation in the coronary circulation is mediated by endothelial M1 receptors (31, 39). In contrast, studies in various other species, including cattle, horses, monkeys, and mice, have shown that cholinergic dilation of coronary arteries is mediated by M3 receptors (7, 25, 30, 35). Likewise, the M3 receptor was proposed to mediate cholinergic vasodilation in pulmonary arteries from rabbits, rats, and mice (1, 28, 33). In human pulmonary arteries, however, both M1 and M3 receptors were suggested to mediate endothelium-dependent acetylcholine-induced vasorelaxation (29). Multiple reasons may account for these diverse findings. First, most of the studies were performed in different species. Thus distinct expression and function of muscarinic receptors among species may be one important factor explaining the inconsistent findings. Second, the selectivity of most muscarinic receptor agonists and antagonists is known to be limited. For example, the M5 receptor shares very similar functional and ligand-binding properties with the M3 receptor, raising the possibility that responses previously thought to be mediated by M3 receptors may involve the activation of M5 receptors (12). Moreover, even “selective” M1 and M2 antagonists display high affinity for M3 and M4 receptors, respectively (9, 43). Consequently, it is difficult to study the functional roles of distinct muscarinic receptor subtypes by using pharmacological agents of limited selectivity. This becomes especially apparent when multiple receptor subtypes are simultaneously involved in mediating a specific functional response. These difficulties can be overcome by the use of muscarinic receptor knockout mice, as convincingly demonstrated in the present study.

In conclusion, the results of this study provide the first direct evidence that M3 receptors mediate cholinergic vasodilation in cutaneous, skeletal muscle, and renal interlobar arteries. Moreover, our findings clearly indicate that neither M1 nor M5 receptors participate in acetylcholine-induced vasodilation in the three vascular beds tested, since the absence of both of these receptor subtypes did not affect cholinergic vasodilation.

Perspectives

The present study demonstrates that the M3 receptor mediates cholinergic vasodilation in small arteries from various vascular resistance beds. Thus drugs activating this receptor subtype may exert hypotensive effects, which supports the findings of a recent study suggesting that M3 receptor agonists may become beneficial in treating arterial hypertension (49). In contrast, M1 and M5 receptors may represent attractive targets for the selective treatment of local ischemic disorders, since they seem to be functionally relevant in only very few vascular beds. For example, pharmacological activation of M5 receptors may be useful to increase cerebral perfusion in certain pathophysiological conditions, such as Alzheimer's disease and cerebral ischemia (37, 41). Interestingly, several agents have been described recently that can selectivity enhance signaling through M1 or M5 receptors (4, 8, 27, 40). Such ligands may become relevant for the development of novel muscarinic drugs aimed at modulating local perfusion.

GRANTS

This study was supported by a grant from the Ernst und Berta Grimmke Foundation.

DISCLOSURES

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ulrike Neumann for expert technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1. Altiere RJ, Travis DC, Roberts J, Thompson DC. Pharmacological characterization of muscarinic receptors mediating acetylcholine-induced contraction and relaxation in rabbit intrapulmonary arteries. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 270: 269–276, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Beny JL, Nguyen MN, Marino M, Matsui M. Muscarinic receptor knockout mice confirm involvement of M3 receptor in endothelium-dependent vasodilatation in mouse arteries. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 51: 505–512, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boulanger CM, Morrison KJ, Vanhoutte PM. Mediation by M3-muscarinic receptors of both endothelium-dependent contraction and relaxation to acetylcholine in the aorta of the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Br J Pharmacol 112: 519–524, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bridges TM, Marlo JE, Niswender CM, Jones CK, Jadhav SB, Gentry PR, Plumley HC, Weaver CD, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW. Discovery of the first highly M5-preferring muscarinic acetylcholine receptor ligand, an M5 positive allosteric modulator derived from a series of 5-trifluoromethoxy N-benzyl isatins. J Med Chem 52: 3445–3448, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bruning TA, Chang PC, Hendriks MG, Vermeij P, Pfaffendorf M, van Zwieten PA. In vivo characterization of muscarinic receptor subtypes that mediate vasodilatation in patients with essential hypertension. Hypertension 26: 70–77, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bruning TA, Hendriks MG, Chang PC, Kuypers EA, van Zwieten PA. In vivo characterization of vasodilating muscarinic-receptor subtypes in humans. Circ Res 74: 912–919, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brunner F, Kuhberger E, Groschner K, Poch G, Kukovetz WR. Characterization of muscarinic receptors mediating endothelium-dependent relaxation of bovine coronary artery. Eur J Pharmacol 200: 25–33, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Budzik B, Garzya V, Shi D, Foley JJ, Rivero RA, Langmead CJ, Watson J, Wu Z, Forbes IT, Jin J. 2′ Biaryl amides as novel and subtype selective M1 agonists. Part I. Identification, synthesis, and initial SAR. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 20: 3540–3544, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Caulfield MP, Birdsall NJ. International Union of Pharmacology. XVII. Classification of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Pharmacol Rev 50: 279–290, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chiba S, Tsukada M. Possible involvement of muscarinic M1 and M3 receptor subtypes mediating vasodilation in isolated, perfused canine lingual arteries. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 23: 839–843, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dauphin F, Hamel E. Muscarinic receptor subtype mediating vasodilation feline middle cerebral artery exhibits M3 pharmacology. Eur J Pharmacol 178: 203–213, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Eglen RM, Nahorski SR. The muscarinic M5 receptor: a silent or emerging subtype? Br J Pharmacol 130: 13–21, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Elhusseiny A, Hamel E. Muscarinic–but not nicotinic–acetylcholine receptors mediate a nitric oxide-dependent dilation in brain cortical arterioles: a possible role for the M5 receptor subtype. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 20: 298–305, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eltze M, Ullrich B, Mutschler E, Moser U, Bungardt E, Friebe T, Gubitz C, Tacke R, Lambrecht G. Characterization of muscarinic receptors mediating vasodilation in rat perfused kidney. Eur J Pharmacol 238: 343–355, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Faraci FM, Sigmund CD. Vascular biology in genetically altered mice: smaller vessels, bigger insight. Circ Res 85: 1214–1225, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fernandes FA, Alonso MJ, Marin J, Salaices M. M3-muscarinic receptor mediates prejunctional inhibition of noradrenaline release and the relaxation in cat femoral artery. J Pharm Pharmacol 43: 644–649, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fisahn A, Yamada M, Duttaroy A, Gan JW, Deng CX, McBain CJ, Wess J. Muscarinic induction of hippocampal gamma oscillations requires coupling of the M1 receptor to two mixed cation currents. Neuron 33: 615–624, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Flaim SF, Weitzel RL, Zelis R. Mechanism of action of nitroglycerin during exercise in a rat model of heart failure. Improvement of blood flow to the renal, splanchnic, and cutaneous beds. Circ Res 49: 458–468, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Furchgott RF, Zawadzki JV. The obligatory role of endothelial cells in the relaxation of arterial smooth muscle by acetylcholine. Nature 288: 373–376, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gericke A, Mayer VG, Steege A, Patzak A, Neumann U, Grus FH, Joachim SC, Choritz L, Wess J, Pfeiffer N. Cholinergic responses of ophthalmic arteries in M3 and M5 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor knockout mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 50: 4822–4827, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hendriks MG, Pfaffendorf M, Van Zwieten PA. Characterization of the muscarinic receptor subtype mediating vasodilation in the rat perfused mesenteric vascular bed preparation. J Auton Pharmacol 12: 411–420, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hendriks MG, Pfaffendorf M, van Zwieten PA. Characterization of the muscarinic receptors in the mesenteric vascular bed of spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Hypertens 11: 1329–1335, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hsu HH, Duning K, Meyer HH, Stolting M, Weide T, Kreusser S, van Le T, Gerard C, Telgmann R, Brand-Herrmann SM, Pavenstadt H, Bek MJ. Hypertension in mice lacking the CXCR3 chemokine receptor. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 296: F780–F789, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Klonizakis M, Tew G, Michaels J, Saxton J. Impaired microvascular endothelial function is restored by acute lower-limb exercise in post-surgical varicose vein patients. Microvasc Res 77: 158–162, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lamping KG, Wess J, Cui Y, Nuno DW, Faraci FM. Muscarinic (M) receptors in coronary circulation: gene-targeted mice define the role of M2 and M3 receptors in response to acetylcholine. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 24: 1253–1258, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Leung HS, Leung FP, Yao X, Ko WH, Chen ZY, Vanhoutte PM, Huang Y. Endothelial mediators of the acetylcholine-induced relaxation of the rat femoral artery. Vascul Pharmacol 44: 299–308, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ma L, Seager MA, Wittmann M, Jacobson M, Bickel D, Burno M, Jones K, Graufelds VK, Xu G, Pearson M, McCampbell A, Gaspar R, Shughrue P, Danziger A, Regan C, Flick R, Pascarella D, Garson S, Doran S, Kreatsoulas C, Veng L, Lindsley CW, Shipe W, Kuduk S, Sur C, Kinney G, Seabrook GR, Ray WJ. Selective activation of the M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor achieved by allosteric potentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 15950–15955, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McCormack DG, Mak JC, Minette P, Barnes PJ. Muscarinic receptor subtypes mediating vasodilation in the pulmonary artery. Eur J Pharmacol 158: 293–297, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Norel X, Walch L, Costantino M, Labat C, Gorenne I, Dulmet E, Rossi F, Brink C. M1 and M3 muscarinic receptors in human pulmonary arteries. Br J Pharmacol 119: 149–157, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Obi T, Kabeyama A, Nishio A. Characterization of muscarinic receptor subtype mediating contraction and relaxation in equine coronary artery in vitro. J Vet Pharmacol Ther 17: 226–231, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pelc LR, Daemmgen JW, Gross GJ, Warltier DC. Muscarinic receptor subtypes mediating myocardial blood flow redistribution. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 11: 424–431, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pesic S, Jovanovic A, Grbovic L. Muscarinic receptor subtypes mediating vasorelaxation of the perforating branch of the human internal mammary artery. Pharmacology 63: 185–190, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Peyter AC, Muehlethaler V, Liaudet L, Marino M, Di Bernardo S, Diaceri G, Tolsa JF. Muscarinic receptor M1 and phosphodiesterase 1 are key determinants in pulmonary vascular dysfunction following perinatal hypoxia in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 295: L201–L213, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Phillips JK, Vidovic M, Hill CE. Variation in mRNA expression of alpha-adrenergic, neurokinin and muscarinic receptors amongst four arteries of the rat. J Auton Nerv Syst 62: 85–93, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ren LM, Nakane T, Chiba S. Muscarinic receptor subtypes mediating vasodilation and vasoconstriction in isolated, perfused simian coronary arteries. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 22: 841–846, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ryberg AT, Selberg H, Soukup O, Gradin K, Tobin G. Cholinergic submandibular effects and muscarinic receptor expression in blood vessels of the rat. Arch Oral Biol 53: 605–616, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Scremin OU, Jenden DJ. Cholinergic control of cerebral blood flow in stroke, trauma and aging. Life Sci 58: 2011–2018, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shimizu T, Rosenblum WI, Nelson GH. M3 and M1 receptors in cerebral arterioles in vivo: evidence for downregulated or ineffective M1 when endothelium is intact. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 264: H665–H669, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Simonsen U, Prieto D, Rivera L, Hernandez M, Mulvany MJ, Garcia-Sacristan A. Heterogeneity of muscarinic receptors in lamb isolated coronary resistance arteries. Br J Pharmacol 109: 998–1007, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Stahl E, Ellis J. Novel allosteric effects of amiodarone at the muscarinic M5 receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 334: 214–222, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tong XK, Hamel E. Regional cholinergic denervation of cortical microvessels and nitric oxide synthase-containing neurons in Alzheimer's disease. Neuroscience 92: 163–175, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Vita JA, Treasure CB, Nabel EG, McLenachan JM, Fish RD, Yeung AC, Vekshtein VI, Selwyn AP, Ganz P. Coronary vasomotor response to acetylcholine relates to risk factors for coronary artery disease. Circulation 81: 491–497, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wess J. Molecular biology of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Crit Rev Neurobiol 10: 69–99, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wess J. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor knockout mice: novel phenotypes and clinical implications. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 44: 423–450, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wess J, Eglen RM, Gautam D. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors: mutant mice provide new insights for drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov 6: 721–733, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yamada M, Lamping KG, Duttaroy A, Zhang W, Cui Y, Bymaster FP, McKinzie DL, Felder CC, Deng CX, Faraci FM, Wess J. Cholinergic dilation of cerebral blood vessels is abolished in M5 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 14096–14101, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yamada M, Miyakawa T, Duttaroy A, Yamanaka A, Moriguchi T, Makita R, Ogawa M, Chou CJ, Xia B, Crawley JN, Felder CC, Deng CX, Wess J. Mice lacking the M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor are hypophagic and lean. Nature 410: 207–212, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zagvazdin Y, Fitzgerald ME, Reiner A. Role of muscarinic cholinergic transmission in Edinger-Westphal nucleus-induced choroidal vasodilation in pigeon. Exp Eye Res 70: 315–327, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zapata-Sudo G, Pereira SL, Beiral HJ, Kummerle AE, Raimundo JM, Antunes F, Sudo RT, Barreiro EJ, Fraga CA. Pharmacological characterization of (3-thienylidene)-3,4-methylenedioxybenzoylhydrazide: a novel muscarinic agonist with antihypertensive profile. Am J Hypertens 23: 135–141, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]