Abstract

Surgical ventricular restoration (SVR) was designed to treat patients with aneurysms or large akinetic walls and dilated ventricles. Yet, crucial aspects essential to the efficacy of this procedure like optimal shape and size of the left ventricle (LV) are still debatable. The objective of this study is to quantify the efficacy of SVR based on LV regional shape in terms of curvedness, wall stress, and ventricular systolic function. A total of 40 patients underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) before and after SVR. Both short-axis and long-axis MRI were used to reconstruct end-diastolic and end-systolic three-dimensional LV geometry. The regional shape in terms of surface curvedness, wall thickness, and wall stress indexes were determined for the entire LV. The infarct, border, and remote zones were defined in terms of end-diastolic wall thickness. The LV global systolic function in terms of global ejection fraction, the ratio between stroke work (SW) and end-diastolic volume (SW/EDV), the maximal rate of change of pressure-normalized stress (dσ*/dtmax), and the regional function in terms of surface area change were examined. The LV end-diastolic and end-systolic volumes were significantly reduced, and global systolic function was improved in ejection fraction, SW/EDV, and dσ*/dtmax. In addition, the end-diastolic and end-systolic stresses in all zones were reduced. Although there was a slight increase in regional curvedness and surface area change in each zone, the change was not significant. Also, while SVR reduced LV wall stress with increased global LV systolic function, regional LV shape and function did not significantly improve.

Keywords: ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy, magnetic resonance imaging, curvature, left ventricular remodeling

surgical ventricular restoration (SVR) has been used to treat patients with left ventricular (LV) dysfunction and akinetic or dyskinetic segments from prior anterior myocardial infarction (MI). Several studies have documented that this procedure can be performed with reasonably low operative mortality and results in good patient outcomes (2, 28, 30, 34). The recent result of The Surgical Treatment for Ischemic Heart Failure (STICH) Trial, however, showed that SVR did not improve survival, hospitalization, and quality of life over coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) alone after 4 yr of follow-up (21). The underlying reasons of this failure have been speculated as follows: 1) progressive LV dilation and distortion may occur after SVR (19), and 2) the long-term effects of SVR on LV diastolic dysfunction may contribute to the worsening of heart failure (7).

An additional issue is whether SVR will produce an optimal ventricular shape and size. Buckberg and colleague (6) endorsed the concept that the creation of an elliptical shape rather than a spherical shape may provide an optimal LV deformation. Furthermore, LV wall stress reduction after surgery has been believed to reverse adverse ventricular remodeling. Finite element analysis in animal studies (13, 25, 39) have shown a decreased LV wall stress in remote, border, and infarct zones (RZ, BZ, and IZ, respectively). To date, the effects of SVR on LV regional shape and regional wall stress have not been analyzed in humans.

We have recently developed a new method to determine LV regional shape in terms of curvedness and wall stress based on three-dimensional (3-D) LV models reconstructed from magnetic resonance (MR) imaging (MRI) (41). Patients with ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy had significantly smaller LV regional curvedness (in particular at the apex region) and higher wall stress in all segments compared with normal healthy subjects (41). The goal of the present study is to examine LV regional shape, wall stress, and systolic function before and after SVR in a clinical population.

METHODS

Study population.

We performed a retrospective analysis of prospectively consecutively acquired MRI data of 40 patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy, who had undergone CABG combined with SVR. In some of these patients, there had been concomitant mitral regurgitation that required mitral valve repair surgery (MVS) by means of restrictive mitral annuloplasty. In each case, the SVR procedure was performed by means of endoventricular circular patch plasty as previously described by Dor and associates (18). All patients underwent a full pre- and post-SVR MRI protocol. The study was approved by the Cleveland Clinic Institutional Review Committee, and all patients gave informed consent.

MRI image acquisition.

MRI studies were performed 1 to 2 wk before surgery and 1 to 2 wk after surgery on a 1.5-T MRI scanner (Siemens Somatom, Erlangen, Germany), equipped with fast gradients (23-mT/m amplitude, 105-mT/m per ms slew rate) and a dedicated cardiac phased-array surface coil. ECG-gated consecutive cine short-axis views were acquired to cover the LV, using breath-held steady-state free-precession technique (echo time, 1.4 ms; repetition time, 2.9 ms; slice thickness, 8 mm; flip angle, 60°; spatial resolution, 1.4×1.2 mm2; and temporal resolution, 42 ms). Both long-axis and short-axis views were obtained to determine the 3-D LV shape.

Determination of LV geometry.

The MRI studies were reviewed on a commercially available computer workstation using a commercially available software (CMRtools, Cardiovascular Imaging Solution). A manual tracing of the epicardial and endocardial borders of contiguous short-axis slices enabled a reconstruction of the LV 3-D shape and allowed a calculation of LV end-diastolic volume (EDV), end-systolic volume (ESV), stroke volume (SV), ejection fraction (EF), and LV mass. The LV mass (in g) was derived from the product of myocardial volume and specific density of the myocardium (1.05 g/cm3) (22). The papillary muscles were included in the mass but excluded from the volumes.

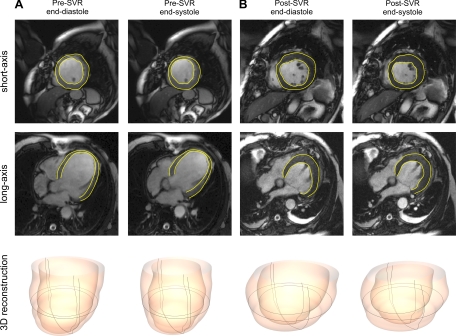

The global shape of the LV was characterized by means of the sphericity index, which is the ratio of the short axis to the long axis, and was calculated in systole and diastole (24). A normalized measure of the sphericity index (SLv) was also calculated in terms of the volume ratio of the LV volume and a theoretical sphere volume of 1/6π × L3, where L is the long axis of the LV, as defined by Kono et al. (24). Figure 1 shows a sample MRI-obtained short-axis view and a four-chamber long-axis view, along with the reconstructed LV shape before and after SVR.

Fig. 1.

Magnetic resonance image showing a short-axis slice (top) at the level of the equator and long-axis slice (middle) at end diastole and end systole, with the left ventricular endocardial and epicardial surfaces denoted by yellow lines. Its corresponding three-dimensional (3-D) reconstructed left ventricular shape (bottom) at end diastole and end systole are shown before (A) and after (B) surgical ventricular restoration (SVR).

Determination of LV regional shape and geometric parameters: curvedness, LV radius and wall thickness, and endocardial surface area.

A validated triangulation algorithm was used to reconstruct the 3-D model of the LV endocardial surface for each patient from the aforementioned steady-state free-precession short-axis and long-axis cine images (38). The LV surface properties were computed via an analytical approach, using a surface-fitting method from the reconstructed 3-D model of the LV (Fig. 1), as previously described (41). An in-house algorithm was used to calculate the maximum and minimum principal curvatures for each point on the surface, and the local curvedness was calculated as the root mean square of these principal curvatures (38). The regional LV radius (R) and wall thickness (T) were deduced from the 3-D geometry of the LV. This procedure accounts for the 3-D geometry and hence avoids the errors incurred by typical two-dimensional (2-D) methods (41). The endocardial surface area (S) was determined, and its change [ΔS = (SED − SES)/SED × 100%] from end diastole to end systole was calculated.

Determination of LV systolic function and vascular function.

The LV systolic properties were assessed by a determination of LV performance and systolic function indexes (4, 42). These LV systolic properties are described as 1) LV systolic performance in terms of stroke work (SW), calculated as the product of SV and mean arterial pressure (4); 2) LV systolic function in terms of the EF, and the SW index of the ratio of SW and EDV (SW/EDV) and LV contractility index maximal rate of change of pressure-normalized stress (dσ*/dtmax), assessed as 1.5 × dV/dtmax/Vm, as previously validated (40, 42), where dV/dt is the first derivative of the volume and Vm is the myocardium volume at end diastole; and 3) LV regional systolic function in terms of ΔS.

Vascular function was assessed in terms of 1) effective arterial elastance, estimated as the end-systolic pressure divided by the SV (21); 2) total arterial compliance, estimated by ratio of SV and pulse pressure (9); and 3) systolic vascular resistance index, given by the mean arterial pressure divided by the cardiac index times a conversion factor (80 dyn·cm−2·mmHg−1).

Determination of wall stress indexes at end diastole and end systole.

The wall stress formula was derived based on the equilibrium of forces between the LV cavity pressure (P) and the stresses in the wall (σ). Following Grossman et al. (20), the regional wall stress was determined from the inner radius of curvature (R) and wall thickness (T). In this study, pressure-normalized stress (σ/P) was used as an index of wall stress. Since it is a pure geometric parameter, it represents the physical response of the LV to the loading and allows comparison between ventricles at different pressure and different regions of the same ventricle (26). Accordingly, the pressure-normalized stress (σ/P) and end-systolic wall stress (σES) were calculated in terms of R and T using our in-house developed software (41), such that

| (1) |

| (2) |

where the end-systolic pressure (PES) was estimated as the systolic pressure multiplied by a factor of 0.9, as previously validated (10, 23). In this study, systolic pressure was assessed from the systolic noninvasive blood pressure and a conversion of 0.133 was used to express the final results (in kPa) (41).

Definition of BZ and RZ.

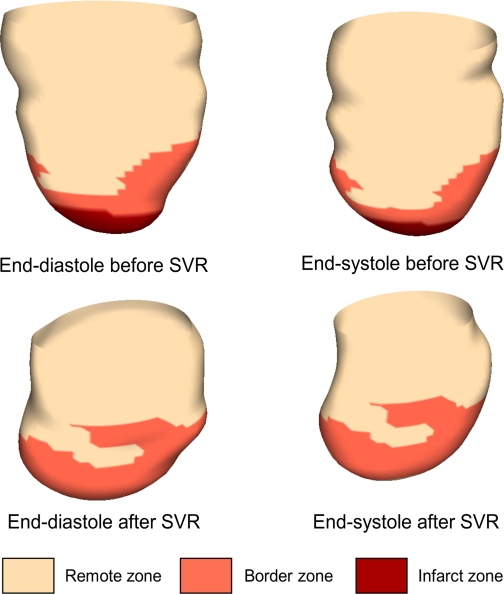

Similar to previous studies, we identified the BZ from the MR images as the region where the LV wall thickness at end diastole varied between normal (8 to 12 mm) to thin (<5 mm) (25). In other words, the BZ was identified as the transition zone between normally thick myocardium (RZ) and the infarcted myocardium (IZ). Thus IZ, BZ, and RZ were anatomically specified throughout the ventricle (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

3-D geometry of the left ventricle before and after SVR. Surface was classified into 3 regions: remote zone (RZ), border zone (BZ), and infarcted zone (IZ).

Statistical analysis.

All variables are presented as means ± SD. Student's paired t-test was used to assess any significant differences between measurements. The difference in curvedness and wall stress indexes among the various zones were assessed by ANOVA. Associations among variables were explored by using Pearson or Spearman rank correlation coefficient as appropriate. A P value < 0.05 was considered significant. A commercially available statistical software package was used for data analysis (SPSS, version 15, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Subject characteristics.

All 40 patients were treated with CABG and SVR (endoventricular circular patch plasty) (Table 1). The age of the patients averaged 69 yr old (range, 52–84 yr old). Among them, 19 patients had severe mitral regurgitation and received additional MVS and 28 patients had congestive heart failure.

Table 1.

Patients characteristics and clinical data

| Variables | Value |

|---|---|

| Male:female | 36:4 |

| Age, yr | 69 ± 9 |

| Body surface area, m2 | 1.98 ± 0.18 |

| LV ejection fraction, % | 26 ± 7 |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 39 (98) |

| Congestive heart failure, n (%) | 28 (70) |

| New York Heart Association class | |

| I and II, n (%) | 26 (65) |

| III and IV, n (%) | 14 (35) |

| Surgery | |

| SVR + CABG, n (%) | 21 (52) |

| SVR + CABG + MVS, n (%) | 19 (48) |

Values are means ± SD or numbers of patients (percentages). LV, left ventricular; SVR, surgical ventricular restoration; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; MVS, mitral valve surgery.

LV geometry.

After SVR, there was a significant decrease in the dimensions of both the long- and short-axes of the LV. The long-axis dimension of the LV decreased more than the short-axis dimension, however, which resulted in an increase of the sphericity index after SVR (sphericity index at diastole, 0.65 ± 0.087 vs. 0.81 ± 0.11, P < 0.001; sphericity index at systole, 0.57 ± 0.094 vs. 0.67 ± 0.13, P < 0.001; SLv at diastole, 0.47 ± 0.14 vs. 0.74 ± 0.21, P < 0.001; and SLv at systole, 0.41 ± 0.14 vs. 0.61 ± 0.20, P < 0.001). There were also significant reductions in the EDV index, ESV index, LV SV index, and LV mass index after SVR (Table 2).

Table 2.

Measures of ventricular structure and function

| Pre-SVR | Post-SVR | |

|---|---|---|

| n | 40 | 40 |

| LV Structure | ||

| End-diastolic volume index, ml/m2 | 156 ± 39 | 110 ± 33c |

| End-systolic volume index, ml/m2 | 117 ± 39 | 77 ± 31c |

| Stroke volume index, ml/m2 | 39 ± 9 | 33 ± 8c |

| Cardiac index, l·min−1·m−2 | 2.84 ± 0.74 | 2.59 ± 0.74a |

| LV mass index, g/m2 | 112 ± 25 | 101 ± 23c |

| Sphericity index_ed | 0.65 ± 0.087 | 0.81 ± 0.11c |

| Sphericity index_es | 0.57 ± 0.094 | 0.67 ± 0.13c |

| SLv_ed | 0.47 ± 0.14 | 0.74 ± 0.21c |

| SLv_es | 0.41 ± 0.14 | 0.61 ± 0.20c |

| LV Systolic function | ||

| SW, mmHg·l | 6.61 ± 1.96 | 5.46 ± 1.64c |

| SW/EDV, mmHg | 21.76 ± 8.25 | 25.64 ± 7.40 |

| Ejection fraction, % | 26 ± 7 | 31 ± 10c |

| dσ*/dtmax, s−1 | 2.69 ± 0.74 | 3.23 ± 0.73c |

| End-diastolic infarct surface area, % | 27 ± 14 | 3 ± 4c |

| SED, cm2 | 184 ± 30 | 140 ± 36c |

| SES, cm2 | 155 ± 32 | 117 ± 33c |

| ΔS, % | 16 ± 7 | 18 ± 9 |

| Vascular Function | ||

| Ea, mmHg/ml | 1.41 ± 0.37 | 1.66 ± 0.40b |

| Systemic vascular resistance index, dyn·s·cm−5·m2 | 2488 ± 624 | 2759 ± 773a |

| Arterial compliance, ml/mmHg | 1.84 ± 0.63 | 1.51 ± 0.36b |

Values are means ± SD; n, number of patients. EDV, end-diastolic (ed) volume; ESV, end-systolic (es) volume; SLv, normalized measure of the sphericity index calculated in terms of the volume ratio of the LV volume and a theoretical sphere volume; SW, stroke work; S, surface area; ΔS, surface area change from end diastole to end systole; dσ*/dtmax, maximal rate of change of pressure-normalized stress; Ea, effective arterial elastance.

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01, and

P < 0.001 for 2-tail paired t-test used in comparing pre- and post-SVR values.

Regional geometric parameters.

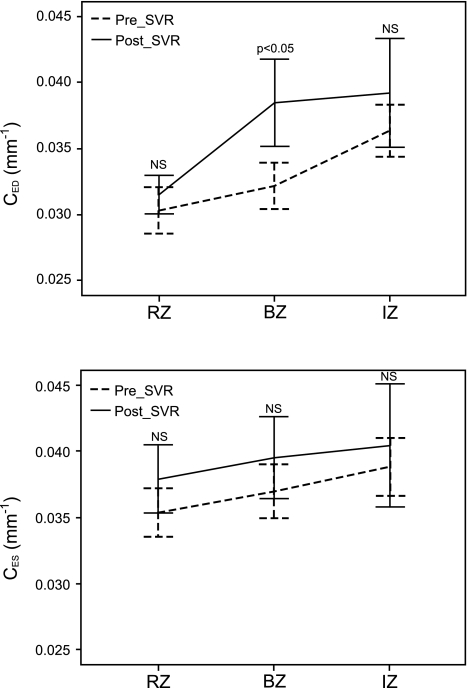

The calculated regional geometric parameters for curvedness, radius of curvature, and ratio of radius vs. wall thickness (R/T) in patients before and after SVR are summarized in Table 3. Before SVR, the curvedness is small in all regions, averaging 0.033 mm−1 at end diastole (compared with 0.043 mm−1 in the normal heart) and 0.037 mm−1 at end systole (compared with normal value of 0.075 mm−1). The highest curvedness values are found in the IZ (≈0.039 mm−1), whereas the smallest curvedness values are found in RZ. There are increases of both R/TED and R/TES from RZ to IZ. There was a slight increase in curvedness in RZ, BZ, and IZ (7, 18, and 8%, respectively) at end diastole and (9, 5, and 3%, respectively) at end systole after SVR (Fig. 3, and Table 3), but the change was not statistically significant. However, there were significant decreases in R/TED and R/TES in all zones.

Table 3.

Comparison of characteristic local parameters in IZ, BZ, and RZ pre- and post-SVR

| Pre-SVR |

Post-SVR |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RZ | BZ | IZ | RZ | BZ | IZ | |

| CED, mm−1 | 0.030 ± 0.006 | 0.032 ± 0.005 | 0.036 ± 0.006 | 0.032 ± 0.005 | 0.038 ± 0.01a | 0.039 ± 0.010 |

| CES, mm−1 | 0.035 ± 0.006 | 0.037 ± 0.006 | 0.039 ± 0.007 | 0.038 ± 0.008 | 0.039 ± 0.01 | 0.040 ± 0.011 |

| RED, mm | 38 ± 5 | 36 ± 5 | 32 ± 5 | 36 ± 5 | 31 ± 6a | 28 ± 7 |

| RES, mm | 33 ± 4 | 31 ± 5 | 30 ± 5 | 31 ± 5 | 29 ± 6 | 28 ± 8 |

| R/TED | 4.31 ± 0.88 | 5.92 ± 0.87 | 8.29 ± 1.56 | 3.82 ± 0.74b | 4.84 ± 1.10c | 6.28 ± 1.38c |

| R/TES | 3.49 ± 0.91 | 4.50 ± 0.95 | 6.48 ± 1.75 | 2.91 ± 0.80b | 3.33 ± 1.04c | 3.90 ± 1.01c |

| SED, cm2 | 79 ± 44 | 57 ± 25 | 50 ± 24 | 109 ± 35b | 28 ± 30c | 7 ± 8c |

| SES, cm2 | 66 ± 40 | 47 ± 22 | 43 ± 22 | 91 ± 33b | 23 ± 27c | 6 ± 7c |

| ΔS, % | 16 ± 8 | 17 ± 8 | 14 ± 7 | 17 ± 9 | 21 ± 14 | 14 ± 4 |

| σ/PED | 1.98 ± 0.42 | 2.76 ± 0.44 | 4.04 ± 0.88 | 1.72 ± 0.37b | 2.20 ± 0.55c | 2.94 ± 0.71c |

| σ/PES | 1.62 ± 0.44 | 2.14 ± 0.50 | 3.22 ± 0.97 | 1.28 ± 0.41c | 1.47 ± 0.53c | 1.76 ± 0.50c |

| σES, kPa | 22 ± 6 | 29 ± 7 | 43 ± 12 | 17 ± 5c | 20 ± 6c | 23 ± 6c |

Values are means ± SD. RZ, remote zone; BZ, border zone; IZ, infarcted zone; CED, ventricular wall curvedness at end diastole; CES, ventricular wall curvedness at end systole; RED, ventricular chamber radius of curvedness at end-diastole; RES, ventricular chamber radius of curvedness at end systole; TED, ventricular wall thickness at end diastole; TES, ventricular wall thickness at end systole; SED, ventricular surface area at end diastole; SES, ventricular surface area at end systole; ΔS, ventricular surface area change from end diastole to end systole; σ/PED, normalized wall stress at end diastole; σ/PES, normalized wall stress at end diastole; σES, ventricular wall stress at end systole.

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01,

P < 0.001 for 2-tail paired t-test used in comparing pre- and post-SVR values.

Fig. 3.

Left ventricular regional curvedness at end diastole (CED) and end systole (CES) in RZ, BZ, and IZ before and after SVR. There is no significantly change in curvedness in each zone. *P < 0.05, pre- vs. post-SVR. NS, not significant.

LV function and vascular function.

As shown in Table 2, there was a decreased EDV index from 156 ± 39 to 110 ± 33 ml/m2 and ESV index from 117 ± 39 to 77 ± 31 ml/m2, postoperatively. The mean EF increased significantly from 26 ± 7 to 31 ± 10%. Similarly, there was increase in SW/EDV from 21.76 ± 8.25 to 25.64 ± 7.40 mmHg and in dσ*/dtmax from 2.69 ± 0.74 to 3.23 ± 0.73 s−1 after SVR. Surprisingly, there were significant decreases in cardiac index from 2.84 ± 0.74 to 2.59 ± 0.74 l·min−1·m−2 and SW from 6.61 ± 1.96 to 5.46 ± 1.64 mmHg·l post-SVR. In addition, arterial elastance and systemic vascular resistance index were increased and arterial compliance was significantly decreased, mainly because SV had decreased. Although there was slight improvement in ΔS, the change was not significant.

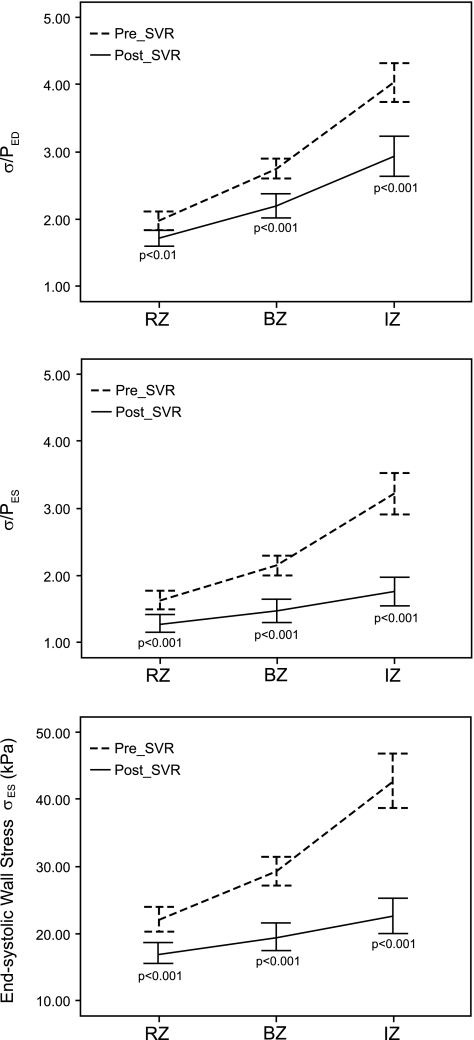

Regional wall stress indexes at end diastole and end systole.

As seen in Table 3 and Fig. 4, there were decreases in σ/P at both end diastole and end systole after surgery. The σ/PED decreased by 27% from 4.04 ± 0.88 to 2.94 ± 0.71 (P < 0.001) in the IZ, by 20% in the BZ from 2.76 ± 0.44 to 2.20 ± 0.55 (P < 0.001), and by 9% in the RZ from 1.90 ± 0.42 to 1.72 ± 0.37 (P < 0.05). At end systole, σ/PES decreased by 45% in the IZ from 3.22 ± 0.97 to 1.76 ± 0.50 (P < 0.0001), by 31% in the BZ from 2.14 ± 0.50 to 1.47 ± 0.53 (P < 0.001), and by 21% in the RZ from 1.62 ± 0.44 to 1.28 ± 0.41 (P < 0.05). Similarly, the end-systolic wall stress decreased at each zone, respectively (IZ, pre-SVR = 43 ± 12 kPa, and post-SVR = 23 ± 6 kPa; BZ, pre-SVR = 29 ± 7 kPa, and post-SVR = 20 ± 6 kPa; and RZ, pre-SVR = 22 ± 6 kPa2, and post-SVR = 17 ± 5 kPa; all, P < 0.001).

Fig. 4.

Left ventricular regional wall stress indexes at end diastole (σ/PED) and end systole (σ/PES) and end-systolic wall stress (σES) in RZ, BZ, and IZ before and after SVR. End-diastolic wall stress index decreased significantly in each zone.

Effect of MVS.

The cases were further divided into patients with and without MVS (MVS = 19). Patients with MVS had a higher global EDV index and ESV index relative to patients without MVS, but this was not statistically significant. Patients with MVS also had lower global LV systolic function performance in EF, SW/EDV, end-systolic elastance, and dσ*/dtmax but higher σ/PED and σ/PES. SVR brought decreased global EDV index, ESV index, σ/PED, and σ/PES, suggesting improved LV systolic function. The multivariate general linear model analysis showed that the MVS procedure did not impact changes in LV parameters (P > 0.05). Hence, all the data presented above were grouped over the 40 patients.

DISCUSSION

In this first analysis of 3-D LV regional shape for patients pre- and post-SVR, SVR reduces wall stresses, improves LV global systolic function, but fails to improve regional shape in humans. This failure to restore LV shape to optimal (e.g., normal elliptical ventricle) may contribute to diastolic dysfunction in the long term.

Effect of SVR on LV shape.

MI can result in a spectrum of LV shape abnormalities, related to the extent of myocardial damage (3, 31, 32). SVR aims to reshape the LV, rebuild a more physiological LV chamber, and improve cardiac pump function (6). However, some studies have reported that LV became more spherical in terms of global sphericity index after SVR (14, 27, 40). The focus on global sphericity index may be misleading since the single plane ratio reflects a linear alteration in the two axes of the ventricular chamber. Di Donato et al. proposed a conical index to assess the LV apical regional abnormalities and found an increased value of conical index in post-MI patients (15) and a significant decrease after SVR (14), whereas the sphericity index does not change and, in some cases, even increases. This discrepancy may be due to the focus on 2-D indexes, which lack 3-D details of the LV. The introduction of the curvedness index may help to better identify 3-D LV regional shape changes after MI and postsurgery. A decrease of curvedness is observed in post-MI patients, in particular at the apex zone (41).

In the present study, SVR did not significantly change LV regional shape in all zones (see Table 3). In our previous study, we had reported that end-systolic curvedness in normal heart is ∼0.05, 0.06, and 0.10 mm−1 in the basal, middle, and apical regions, respectively. It should be noted that SVR increases end-systolic curvedness to 0.038, 0.039, and 0.040 mm−1 in the RZ, BZ, and IZ, respectively, but may not “optimize” ventricular shape. This remaining distortion may cause nonoptimal filling and diastolic dysfunction of the LV. Our observation is consistent with the findings of a recent study that used a combination of computational fluid dynamics and cardiac MR techniques (17). It was found that post-SVR shape is more spherical than preoperative and healthy heart. It appears that “ball”-shaped ventricles have impaired fluid dynamics and fluid washout (17).

Since the objective of SVR is to resize and reshape the LV, this raises the question of what is the ideal volume reduction (residual volume) and what are the geometric implications that may affect the prognosis of patients submitted to SVR. Which is more important in determining clinical outcome remains controversial. In the present study, the surgeon used the Mannequin Endoventricular Shaper (Chase Medical) to measure the residual volume of LV balloon measurement to restore the dilated ventricles to a more optimal ventricular size and shape. Mean preoperative and postoperative LV ESV indexes (LVESVIs) were 117 ± 39 and 77 ± 31 ml/m2. Although the correlations between preoperative and postoperative LVESVI and residual shape (e.g., sphericity index; all, R2 < 0.20) were low, patients with larger preoperative and postoperative LVESVI may trend into more spherical residual shape. Di Donato and coworkers (7) found that both preoperative shape (in terms of conicity index = apex diameter/midwall short diameter) and the EDV difference (residual LV volume) were associated with a worsening of diastolic function after SVR in 146 patients (7). From the same group, 178 patients were retrospectively reviewed and grouped in three categories in terms of LV shape based on echocardiography (type 1, true aneurysm; type 2, nonaneurysmal lesions defined as intermediate cardiomyopathy; and type 3, ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy). SVR induced significant improvement in cardiac and clinical status, regardless of LV shape types. Mortality was higher, however, in types 2 and 3 (14). They also found that residual LVESVI (≥60 ml/m2) predicts survival following SVR (hazard ratio = 10.7, P = 0.001) in 216 patients (16). All three studies cited used 2-D echocardiography to assess LV ESV and shape. As we have shown in the present study, 3-D MRI based indexes may provide a more accurate description of anatomy and hence of function of the heart.

The STICH Trial (21) demonstrated that there was no difference in clinical outcome between SVR + CABG compared with CABG alone. Furthermore, the subgroup by Michler et al. (29) suggested that no threshold of LVESVI at baseline, LVESVI at 4-mo postoperation, or ESV index volume change identified a patient group that benefited from adding SVR to CABG. In summary, the issue of which parameter is more important in determining the clinical outcome (residual volume or shape) remains unclear and is currently of significant interest to cardiology and surgery as evidenced by recent editorials (5, 33).

Effect of SVR on LV wall stress.

Studies of LV wall stress have provided substantial insights into cardiac remodeling (11, 12). The inability of the remaining viable myocardium to compensate for the increased wall stress associated with LV dilatation and thinning is one trigger of LV enlargement after MI (1). The primary effect of SVR is to reduce LV wall stress, and there is evidence for this occurrence (13, 36, 37, 39, 40). Despite its obvious importance, however, wall stress is difficult to measure after MI because of the heterogeneous deformation of the LV chamber. The proposed 3-D MRI-based methodology for 3-D reconstruction (accompanied by local radius-of-curvature and thickness determination) and use of Eq. 1 is computationally much more efficient and easier to implement. This 3-D approach (41) is found to be more accurate than existing 2-D approaches for a precise evaluation of the regional wall stress. In this study, the LV end-systolic wall stress was reduced to 17 ± 5, 20 ± 6, and 23 ± 6 kPa at RZ, BZ, and IZ, respectively. In our previous study, we have reported that peak systolic stress in normal heart was ∼10 kPa. Hence, it should be noted that while SVR reduces end-systolic wall stress, it does not succeed in restoring the stress to normal values.

It is questionable whether SVR is a worthwhile intervention despite the reduction in end-systolic wall stress after the procedure. The amount of stress reduction necessary to halt or reverse nonischemic infarct extension in the BZ is unknown. In animal models, Guccione and colleagues (35) have demonstrated that reduced wall stress does not result in improved BZ contractile function because the inherent contractile function of the myocytes in this region is irreversibly impaired (35). Based on the STICH Trial, it appears that reduced wall stress does not result in improved symptoms nor increases longevity for that patient cohort.

Effect of SVR on ventricular systolic function.

The effect of SVR on LV systolic function has been documented in terms of EF (2, 28, 30, 34). One can criticize the use of EF, however, since SVR directly reduces LV EDV. Hence, by default the EF will increase after SVR. In this study, we measured several indexes to assess LV systolic function. It was hypothesized that if multiple indexes are employed and if the results are generally in agreement and viewed in aggregate, it should be possible to determine and conclude whether patients after SVR have significant improvement in LV systolic function. Our results have shown that there were significant improvements in LV systolic function after SVR (Table 2). Previously, LV systolic function improvement after SVR has also been demonstrated in terms of some loading-independent LV contractile indexes such as end-systolic elastance from invasive pressure-volume measurements (36). These improvements of systolic function after SVR, however, may be due to concurrent CABG. It is well known that viable but dysfunctional myocardium exists in about 50% of patients undergoing CABG and revascularization can lead to striking changes in the LV parameters because of functional recovery. The viability analysis and the potential contribution of CABG as opposed to SVR is a logical next step.

Limitations.

The equation used to calculate the local wall stress is based on the assumption that shear stresses are negligible. Furthermore, the present analysis cannot account for varying myofiber orientation or regional material properties (i.e., a stiffer aneurysm), as in finite element model (37, 39). Clearly, complex finite element models may eventually give more accurate results, but this remains challenging and computationally more costly. The IZ, BZ, and RZ were classified in terms of anatomical definition, but not from myocardial viability late-gadolinium technique. Finally, it is unclear whether the improvement in systolic function is due to SVR or CABG since the patients undergo both procedures and we do not have a group with only pre- and post-CABG to assess the effect of each.

Implications and significance.

When compared with CABG alone, SVR confers additional effects on LV volume reduction and wall stress (13, 37, 39). However, the recent results of the STICH Trial showed that SVR did not improve survival, hospitalization, and quality of life over CABG alone after 4 yr of follow-up (21). One possible explanation is that SVR disrupts the 3-D helical structure of the myocardium (19), which impairs LV diastolic function (37), to the extent that the benefits of reduced wall stress and improved LV systolic function are negated. Furthermore, some or most of the improvements in systolic function are due to CABG, since revascularization is well known to improve contractility. Finally, some potential negative consequences of the SVR procedure are suture line or patch dehiscence, excessive LV volume reduction, and remaining distorted shape with resulting pathophysiology. The clinical advantage of SVR may be neutral (21) because regional LV shape and function (as assessed with ΔS) do not improve significantly.

There is no doubt that LV remodeling and its role in heart failure progression are multimechanistic and complex including alterations in shape, function, and wall stress. A key issue is that the characterization of LV remodeling generated from clinical images must be functionally accurate to ensure that patients receive optimal therapy. The challenge is to develop more specific measures of LV remodeling beyond LV ESV that can be incorporated into the clinical management pathway. This will help improve the choice of suitable diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. The present study provides quantitative descriptors of cardiac MR images for regional cardiac function. As shown in previous studies (37–42) and here, these indexes may provide a more accurate description of anatomy and hence of heart function. We speculate that the indexes proposed here may provide better predictors of long-term outcomes and should be the subject of future clinical investigations.

GRANTS

This work was supported in part by a research grant from the Agency of Science, Technology and Research; Science and Engineering Research Council Grant 0921480071; SingHealth Foundation Grant SHF/FG408P/2009; and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-086400.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- 1. Aikawa Y, Rohde L, Plehn J, Greaves SC, Menapace F, Arnold MO, Rouleau JL, Pfeffer MA, Lee RT, Solomon SD. Regional wall stress predicts LV remodeling after anteroseptal myocardial infarction in the healing and early afterload reducing trial (HEART): an echocardiography-based structural analysis. Am Heart J 141: 234–242, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Athanasuleas CL, Stanley AW, Jr, Buckberg GD, Dor V, Di Donato M, Blackstone EH. Surgical anterior ventricular endocardial restoration (SAVER) in the dilated remodeled ventricle after anterior myocardial infarction. RESTORE group Reconstructive Endoventricular Surgery, returning Torsion Original Radius Elliptical Shape to the LV. J Am Coll Cardiol 37: 1199–1209, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bogaert J, Bosmans H, Maes A, Suetens P, Marchal G, Rademakers FE. Remote myocardial dysfunction after acute anterior myocardial infarction: impact of left ventricular shape in regional function. J Am Coll Cardiol 35: 1525–1534, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Braunwald E. Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Disease. (5th ed.) Philadelphia: Saunders, 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Buckberg GD, Athanasuleas CL, Wechsler AS, Beyersdorf F, Conte JV, Strobeck JE. The STICH Trial unraveled. Eur J Heart Fail 12: 1024–1027, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Burkberg GD, Group R. Form versus disease: optimizing geometry during ventricular restoration. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 29, Suppl 1: S238–S244, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Castelvecchio S, Menicanti L, Ranucci M, Di Donato M. Impact of surgical ventricular restoration on diastolic function: implications of shape and residual ventricular size. Ann Thorac Surg 86: 1849–1855, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cerqueira MD, Weissman NJ, Dilsizian V, Jacobs AK, Kaul S, Laskey WK, Pennell DJ, Rumberger JA, Ryan T, Verani MS. Standardized myocardial segmentation and nomenclature for tomographic imaging of the heart. A statement for healthcare professionals from the Cardiac Imaging Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology of the American Heart Association. Circulation 105: 539–542, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chemla D, Hebert JL, Coirault C, Zamani K, Suard I, Colin P, Lecarpentier Y. Total arterial compliance estimated by stroke volume-to-aortic pulse pressure ratio in humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 274: H500–H505, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen CH, Fetics B, Nevo E, Rochitte CE, Chiou KR, Ding PA, Kawaguchi M, Kass DA. Noninvasive single-beat determination of left ventricular end-systolic elastance in humans. J Am Coll Cardiol 38: 2028–2034, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cohn JN. New therapeutic strategies for heart failure: left ventricular remodeling as a target. J Card Fail 10: S200–S201, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cohn JN, Ferrari R, Sharpe N. Cardiac remodeling-concepts and clinical implications: a consensus paper from an international forum on cardiac remodeling. Behalf of an international forum on cardiac remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol 35: 569–582, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dang AB, Guccione JM, Zhang P, Wallace AW, Gorman RC, Gorman JH, 3rd, Ratcliffe MB. Effect of ventricular size and patch stiffness in surgical anterior ventricular restoration: a finite element study. Ann Thorac Surg 79: 185–193, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Di Donato M, Castelvecchio S, Kukulski T, Bussadori C, Giacomazzi F, Frigiola A, Menicanti L. Surgical ventricular restoration on left ventricular shape influence on cardiac function, clinical status and survival. Ann Thorac Surg 87: 455–462, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Di Donato M, Dabic P, Castelvecchio S, Santambrogio C, Brankovic J, Collarini L, Joussef T, Frigiola A, Buckberg G, Menicanti L; RESTORE Group Left ventricular geometry in normal and post- anterior myocardial infarction patients: sphericity index and ‘new’ conicity index comparisons. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 29, Suppl 1: S225–S230, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Di Donato M, Castelvecchio S, Menicanti L. End-systolic volume following surgical ventricular reconstruction impacts survival in patients with ischaemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur J Heart Fail 12: 375–381, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Doenst T, Spiegel K, Reik M, Markl M, Hennig J, Nitzsche S, Beyersdorf F, Oertel H. Fluid-dynamic modeling of the human left ventricle: methodology and application to surgical ventricular reconstruction. Ann Thorac Surg 87: 1187–1195, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dor V, Sabatier M, Di Donato M, Montiglio F, Toso A, Maioli M, Pasque MK, Mickleborough LL. Efficacy of endoventricular patch plasty in large postinfarction akinetic scar and severe left ventricular dysfunction: comparison with a series of large dyskinetic scars. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 116: 50–59, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Eisen HJ. Surgical ventricular reconstruction for heart failure. N Engl J Med 360: 1781–1784, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grossman W, Braunwald E, Mann T, McLaurin L, Green L. Contractile state of the left ventricle in man as evaluated from end-systolic pressure-volume relations. Circulation 56: 845–852, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jones RH, Velazquez EJ, Michler RE, Sopko G, Oh JK, O'Connor CM, Hill JA, Menicanti L, Sadowski Z, Desvigne-Nickens P, Rouleau JL, Lee KL, STICH Hypothesis 2 Investigators ; Coronary bypass surgery with or without surgical ventricular reconstruction. N Engl J Med 360: 1705–1717, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Katz J, Milliken MC, Stray-Gundersen J, Buji LM, Parkley RW, Mitchell JH, Peshock RM. Estimation of human myocardial mass with MR imaging. Radiology 169: 495–498, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kelly RP, Ting CT, Yang TM, Liu CP, Maughan WL, Chang MS, Kass DA. Effective arterial elastance as index of arterial vascular load in humans. Circulation 86: 513–521, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kono T, Sabbah HN, Steain PD, Brymer JF, Khaja F. Left ventricular shape as a determinant of mitral regurgitation in patients with several heart failure secondary to either coronary artery disease or idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 68: 355–359, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lessick J, Sideman S, Azhari H, Marcus M, Grenadier E, Beyar R. Regional three-dimensional geometry and function of left ventricles with fibrous aneurysms. A cine-computed tomography study. Circulation 84: 1072–1086, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lessick J, Sideman S, Azhari H, Shapiro E, Weiss JL, Beyar R. Evaluation of regional load in acute ischemia by three-dimensional curvatures analysis of the left ventricle. Ann Biomed Eng 21: 147–161, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McConnell PI, Michler RE. Surgical ventricular restoration: reshaping the adversely remodeled left ventricle. Coron Artery Dis 15: 91–98, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Menicanti L, Castelvecchio S, Ranucci M, Frigiola A, Santambrogio C, de Vincentiis C, Brankovic J, Di Donato M. Surgical therapy for ischemic heart failure: experience from one single-center with surgical ventricular restoration. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 134: 433–441, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Michler RE, Pohost GM, Wrobel K, Bonow RO, Pirk J, Oh JK, et al. on behalf of the S.T.I.C.H. Investigators Influence of left ventricular volume reduction on outcome after coronary artery bypass grafting with or without surgical ventricular reconstruction (Abstract). J Am Coll Cardiol, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mickleborough LL, Merchant N, Ivanov J, Rao V, Carson S. Left ventricular reconstruction: early and late results. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 128: 27–37, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mitchell GF, Lamas GA, Vaughan DE, Pfeffer MA. Left ventricular remodeling in the year after first anterior myocardial infarction: a quantitative analysis of contractile segment lengths and ventricular shape. J Am Coll Cardiol 19: 1136–1144, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Moustakidis P, Maniar HS, Cupps BP, Absi T, Zheng J, Guccione JM, Sundt TM, Pasque MK. Altered left ventricular geometry changes the border zone temporal distribution of stress in an experimental model of left ventricular aneurysm: a finite element model study. Circulation 106: I168–I175, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rouleau JL, Michler RE, Velazquez EJ, Oh JK, O'Connor CM, Desvigne-Nickens P, Sopko G, Lee KJ, Jones RH. The STICH trial: evidence-based conclusions. Eur J Heart Fail 12: 1028–1030, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sartipy U, Albage A, Lindblom D. The Dor procedure for left ventricular reconstruction. Ten-year clinical experience. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 27: 1005–1010, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sun K, Zhang Z, Suzuki T, Wenk JF, Stander N, Einstein DR, Saloner DA, Wallace AW, Guccione JM, Ratcliffe MB. Dor procedure for dyskinetic anterioapical myocardial infarction fails to improve contractility in the border zone. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 140: 233–239, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tulner SA, Steendijk P, Klautz RJ, Bax JJ, Schalij MJ, van der Wall EE, Dion RA. Surgical ventricular restoration in patients with ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy: evaluation of systolic and diastolic ventricular function, wall stress, dyssynchrony, and mechanical efficiency by pressure-volume loops. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 132: 610–620, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Walker JC, Ratcliffe MB, Zhang P, Wallace AW, Hsu EW, Saloner DA, Guccione JM. Magnetic resonance imaging-based finite element stress analysis after linear repair of left ventricular aneurysm. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 135: 1094–1102, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yeo SY, Zhong L, Su Y, Tan RS, Ghista DN. A curvature-based approach for left ventricular shape analysis from cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Med Biol Eng Comput 47: 313–322, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhang P, Guccione JM, Nicholas SI, Walker JC, Crawford PC, Shamal A, Saloner DA, Wallace AW, Ratcliffe MB. Left ventricular volume and function after endoventricular patch plasty for dyskinetic anteroapical left ventricular aneurysm in sheep. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 130: 1032–1038, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zhong L, Sola S, Tan RS, Ghista DN, Kurra V, Navia JL, Kassab GS. Effects of surgical ventricular restoration on left ventricular contractility assessed by a novel contractility index in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 103: 674–679, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhong L, Su Y, Yeo SY, Tan RS, Ghista DN, Kassab GS. Left ventricular regional wall curvedness and wall stress in patients with ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 296: H573–H584, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhong L, Tan RS, Ghista DN, Ng EY, Chua LP, Kassab GS. Validation of a novel cardiac index of left ventricular contractility in patients. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H2764–H2772, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]