Abstract

Dietary protein is a major stimulant for cholecystokinin (CCK) secretion by the intestinal I cell, however, the mechanism by which protein is detected is unknown. Indirect functional evidence suggests that PepT1 may play a role in CCK-mediated changes in gastric motor function. However, it is unclear whether this oligopeptide transporter directly or indirectly activates the I cell. Using both the CCK-expressing enteroendocrine STC-1 cell and acutely isolated native I cells from CCK-enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) mice, we aimed to determine whether PepT1 directly activates the enteroendocrine cell to elicit CCK secretion in response to oligopeptides. Both STC-1 cells and isolated CCK-eGFP cells expressed PepT1 transcripts. STC-1 cells were activated, as measured by ERK1/2 phosphorylation, by both peptone and the PepT1 substrate Cefaclor; however, the PepT1 inhibitor 4-aminomethyl benzoic acid (AMBA) had no effect on STC-1 cell activity. The PepT1-transportable substrate glycyl-sarcosine dose-dependently decreased gastric motility in anesthetized rats but had no affect on activation of STC-1 cells or on CCK secretion by CCK-eGFP cells. CCK secretion was significantly increased in response to peptone but not to Cefaclor, cephalexin, or Phe-Ala in CCK-eGFP cells. Taken together, the data suggest that PepT1 does not directly mediate CCK secretion in response to PepT1 specific substrates. PepT1, instead, may have an indirect role in protein sensing in the intestine.

Keywords: aromatic amino acids, enteroendocrine, peptide transporter

cholecystokinin (CCK), a gastrointestinal peptide secreted by enteroendocrine “I” cells in the proximal small intestine, mediates gastrointestinal feedback and satiety in response to luminal nutrients. CCK is released in response to dietary protein, particularly protein hydrolysates, and stimulates gallbladder contraction (18), pancreatic enzyme secretion (14, 21), and activation of the CCK1 receptor-mediated vagal afferent pathway to inhibit gastric motility and emptying (7, 9, 32, 43) and reduce food intake (1, 34). Although neural pathways and functional responses to protein detection by the gut wall are well established, it is unclear precisely how protein hydrolysates are detected by the intestinal I cell to stimulate CCK secretion.

Recently, there has been increasing evidence that luminal nutrients can be directly detected by enteroendocrine cells. G protein-coupled receptors have been implicated in fatty acid sensing (15, 22, 36), glucose sensing (19, 30, 33, 38, 42), and protein/amino acid sensing (3–4). Interestingly, intestinal transporters may also provide a nutrient-sensing role in the enteroendocrine cell. The sodium-coupled glucose cotransporter SGLT1 (26, 30, 33) and its related protein SGLT3 (10) are increasingly being acknowledged for their role in luminal glucose sensing by enteroendocrine cells. However, the precise mechanism for protein detection by gut enteroendocrine cells remains unclear.

Given that glucose sensing can occur via an intestinal transporter protein, we were interested in determining whether a similar proton-coupled oligopeptide transporter, PepT1 (8, 25), could function as a protein-sensing mechanism for intestinal I cells. PepT1 is primarily expressed in terminally differentiated small intestinal absorptive epithelial cells (29) and functions as the major conduit for protein absorption in the intestine. Along with a broad array of dipeptides and tripeptides, PepT1 also transports a variety of peptidomimetic drugs such as β-lactam antibiotics, antihypertensive agents (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors), and bestatins (35). Cefaclor, a β-lactam antibiotic, delays gastric emptying through CCK1 receptors in rats (2). Additionally, vagal afferent activation in response to both protein hydrolysates and Cefaclor requires functional PepT1-transporter activity (6), suggesting that PepT1 may also serve as a protein sensor mediating CCK secretion from the I cell in response to dietary protein.

Whether PepT1 acts indirectly or directly on the intestinal I cell is unknown; however, evidence in the murine CCK-secreting pancreatic tumor cell line STC-1 suggests that a direct mechanism exists. Protein hydrolysates and cephalosporin drugs activate cAMP and MAP kinase (ERK1/2) pathways and elevate intracellular calcium concentrations, resulting in an upregulation of CCK gene transcription and CCK secretion, respectively (5, 12, 28). PepT1 may be responsible for membrane depolarization, increased intracellular calcium flux, and hormone secretion in response to direct dipeptide stimulation in the STC-1 cell (23).

Here, we tested the hypothesis that PepT1 directly mediates CCK secretion in response to protein hydrolysates through examination of the role of this oligopeptide transporter in both the activation of the STC-1 cell line and in hormone secretion from acutely isolated intestinal I cells in response to protein hydrolysates, dipeptides, and cephalosporin antibiotics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Unless otherwise stated, all chemicals and drugs were obtained from Sigma Chemicals (St. Louis, MO). BD BactoTryptone was purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). 4-Aminomethylbenzoic acid (4-AMBA) is a competitive nontranslocated inhibitor of PepT1 with a Michaelis constant of ∼3 mM (24). 4-Aminophenylacetic acid (4-APAA) is an inactive analog that is translocated by PepT1 (37). Cefaclor (1 mM) and glycyl-sarcosine (Gly-Sar, 10 mM) are known PepT1 substrates (37). β-Ala-Lys-Ne-AMCA labeled peptide, a known PepT1-transportable substrate used to measure peptide uptake into the cell cytosol (13), was synthesized by J. R. Reeve [University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), School of Medicine].

Animals

Transgenic mice with cholecystokinin promoter-driven enhanced green fluorescent protein (CCK-eGFP) were obtained from the Mutant Mouse Regional Resource Center (University of California, Davis), bred and maintained on regular chow, and used under protocols approved by the National Institutes of Health Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines. Sprague Dawley male rats weighing 200–300 g were maintained and used in compliance with protocols approved by the University of California, Davis Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee.

Cell Culture Conditions and Maintenance

STC-1 cells, Caco-2 cells, and BON cells were donated by Doug Hanahan (University of California, San Francisco), Susan Kelleher (Department of Nutrition, University of California, Davis), and C. M. Townsend Jr. (University of Texas, Galveston, TX), respectively, and maintained in a humidified incubator (37°C, 5% CO2). STC-1 cell media contained Dulbecco's modified Eagles medium (DMEM) with 2.5% FBS, 15% horse serum, and 1% penicillin (5,000 IU/ml)-streptomycin (5,000 μg/ml) solution. Caco-2 cell media contained DMEM, 2.5% FBS, 2% gentamycin (10 mg/ml), and 1 M HEPES solution. BON cell media contained DMEM/F-12 with 10% FBS and 5,000 IU/ml penicillin-streptomycin. STC-1 and BON cells were grown to 80% confluency before experiments. Caco-2 cells were grown to confluency for 3 wk to ensure full differentiation.

Isolation of Intestinal Endocrine Cells

Intestinal endocrine cells were isolated from CCK-eGFP mice as previously described (22). Briefly, the proximal 5–6 cm of duodenum was collected and incubated in 1 mM EDTA-DPBS, followed by 75 U/ml collagenase (Worthington Chemical, CLPSA grade), washed, and filtered. The resulting single cell suspension was sorted based on GFP fluorescence by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (BD FACS ARIA machine; BD Biosciences). For RT-PCR studies, a non-eGFP cell population was simultaneously sorted into a separate collection tube.

RNA Extraction

Enteroendocrine cell lines were collected in TransPrep nucleic acid purification lysis buffer, digested with proteinase K (56°C, 30 min), and homogenized for total RNA extraction using a 6100 semiautomated nucleic acid workstation (Applied Biosystems, San Jose, CA). cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using SuperScript III (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), with random hexadeoxyribonucleotide [pd(N)6] primers. For sorted primary cells, total RNA was extracted using Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and 20% phenol-chloroform isoamyl alcohol (Invitrogen) and reversed transcribed using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems).

Real-Time Quantitative TaqMan PCR

qPCR of enteroendocrine cell lines was performed by the Lucy Whittier Molecular Core Facility at the University of California, Davis School of Veterinary Medicine. All supplies and target probes [mouse PepT1 (Mm00453524_m1; SLC15a1)] and the housekeeping gene mouse GAPDH (Mm99999915_g1) were purchased from Applied Biosystems. The samples were amplified in an ABI PRISM 7900 HTA FAST automated fluorometer, using a 5-μl cDNA sample, and run under the following standard conditions: 2 min at 50°C, 10 min at 95°C, 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C and 60 s at 60°C. Threshold cycle (CT) values were collected at a threshold of 0.04 and baseline values of 3–6. For CCK-eGFP cells, the qPCR reaction was performed using the Applied Biosystems Step One System using the same PepT1 gene expression assay system, the housekeeping gene mouse β-actin (4352933E), and cycling conditions mentioned above. CT values >40 were considered not detectable. Gene expression was analyzed using the comparative CT method (ABI User Bulletin no. 2). For graphical purposes, the relative gene expression (expressed as 2−ΔCT × 10n) was used to demonstrate gene expression relative to the housekeeping gene.

AMCA-Labeled Peptide Uptake Studies

STC-1 cells (passage 7) were plated at a concentration of 0.5 × 106 cells/ml in a six-well cell culture dish lined with poly-l-lysine-coated cover slips. At 75–80% confluency, cells were washed two times with Earl's balanced salt solution (EBSS), followed by a 15-min equilibration with a pH-adjusted EBSS (pH 6.0). After preincubation, buffer was removed, and a 500-μl volume of either 0, 5, or 50 μM AMCA-labeled peptide was added and incubated for 20 min at 37°C, 5% CO2. Following incubation, cover slips were washed two times with ice-cold EBSS and fixed for 20 min in fresh cold 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (PFA-PBS) before mounting on slides. Images were taken with the Provis microscope. Cells that were easily defined were counted across three to five different slides. Clumps of cells that could not be singly differentiated were excluded from counts. Images were analyzed using Scion Image Analysis software (version beta 4.02) by encircling an area of interest drawn around individual whole cells and their nuclei. Total and illuminated (marked) pixels were counted within each area of interest to calculate the cytoplasmic pixel count = [( total pixels − marked pixels)/total pixels]. Data were expressed as the percent marked pixels relative to total pixels. Data were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA with post hoc test. Significance was accepted at P < 0.05.

Activation of the ERK1/2 Phosphorylation Pathway

Response to peptone, cefaclor, and Gly-Sar.

STC-1 cells were exposed to increasing concentrations (0–10%) of milk or soy peptone (n = 6), a single concentration of 1 mM Cefaclor (n = 7), or 10 mM Gly-Sar (n = 6) for 2 min.

PepT1 inhibition studies.

To determine whether PepT1 is required for neuroendocrine cell activation in response to peptone, STC-1 cells (n = 3–5) were preincubated for 5 min in either EBSS or varying concentrations (50 μM, 0.5 mM, or 5 mM) of 4-AMBA or 4-APAA, followed by a 2-min treatment of either 1% soy peptone, 5% milk peptone, or 1 mM Cefaclor.

Protein Extraction, SDS-PAGE, and Western Blot

Protein was extracted from STC-1 cells by scraping into Tris-EDTA suspension buffer [15 mM Tris·Cl, 1.5 mM EDTA in double-distilled H2O (ddH2O), pH 8.0], supplemented with 1% protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma) and 1% Triton X-100. Cells were homogenized by running samples through a 25-gauge needle two to six times, sonicated, and centrifuged (10,000 g, 15 min, 4°C). Protein was quantified with a DC Protein Assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and underwent SDS-PAGE and transfer onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane. The membrane was incubated overnight with anti-p44/p42 phosphorylated MAP kinase [phosphorylated ERK1/2 (pERK1/2), 1:1,000; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA] in 5% BSA-TBST, followed by appropriate horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibodies (1 h, room temperature). The desired protein bands of 44 and 42 kDa were semiquantitatively measured by densitometric analysis.

To obtain total ERK1/2 protein concentrations, the PVDF membranes were stripped (7.6 g Tris base, 20 g SDS, 7 ml 2-mercaptoethanol in 1-liter final volume of ddH2O, pH 6.8), reblocked with 5% milk-TBST, and incubated with anti-p44/p42 MAP kinase (ERK1/2) primary antibody (1:1,000; Cell Signaling) using the same protocol as the phosphorylated antibody above to obtain total ERK1/2. Phosphorylation activity was expressed as a ratio of pERK1/2 to total ERK1/2 and normalized to the EBSS control, such that the result was a fold change from no treatment, arbitrarily set to one.

PepT1 Immunohistochemistry

For frozen tissue sections, anesthetized rats were intracardially perfused with fresh cold 4% PFA-PBS. The duodenum was collected and fixed in 4% PFA-PBS for an additional 2 h and stored in 25% sucrose solution with 0.01% sodium azide until cryosectioned. After being blocked in 5% donkey serum, slides were incubated overnight in goat anti-PepT1 (1:1,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and mouse anti-CCK/gastrin (1:1,000; UCLA CURE no. 9303) primary antibodies, followed by incubation with donkey anti-goat IgG AlexaFluor 488 secondary antibody and donkey anti-mouse IgG AlexaFluor 568 (1:500; Invitrogen). Slides were cover slipped and examined under confocal microscopy.

For immunostaining of partially digested duodenal mucosa of CCK-eGFP BAC transgenic mice, intestinal mucosa was incubated for 5 min in 2.5 mM EDTA-PBS, followed by collagenase (1 mg/ml; 10 min) digestion for 10 min. Cells were collected, filtered in a 40-μM cell strainer (BD Biosciences), and resuspended in a solution of 4% PFA-PBS, 0.1% saponin, and 1% BSA for 5 min. Cells were washed in PBS, blocked with 5% BSA-0.1% saponin in PBS (30 min), incubated with anti-PepT1 antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) at a 1:50, 1:100, or 1:200 dilution overnight at 4°C, and subsequently incubated with an appropriate AlexaFluor 594 secondary antibody (1:500; Invitrogen).

CCK-Releasing Assay

CCK-releasing assays from eGFP-sorted cells were performed as previously described (22). Briefly, cells were suspended in Hank's balanced salt solution supplemented with 10 mM HEPES (with Ca2+/Mg2+) and separated into aliquots (∼1,000 cells/well) into a collagen-coated 96-well plate containing a 2× concentration of ligands. Final concentrations (total volume 200 μl) of ligands tested were 1% tryptone and increasing concentrations of l-Phe-Ala (0.03–30 mM), Gly-Sar (1 mM), Cephalexin (20 mM), Cefaclor (1–10 mM), bombesin (100 mM), 1% bactopeptone, and KCl (50 mM). The cells were incubated with ligand for 30 min at 37°C, 5% CO2. Treatments were tested in triplicate and averaged as one (n) sample. Total CCK content was determined by adding 0.2% Triton X-100 in distilled water in wells designated for total contents. Secretion was halted by placing the plate on ice for 5 min. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation, and 50 μl of supernatant were retrieved and saved at −20°C until measured with the CCK Radioimmunoassay Kit (Alpco Diagnostics, Salem, NH) using the manufacturer's suggested 4-day protocol. Cell viability was assessed following the experiment with Trypan blue exclusion and eGFP fluorescence under epifluorescent microscopy.

Measurement of Gastric Motility

Gastric motility was assessed by manometry in urethane-anesthetized rats as previously described (31). Intragastric pressure (IGP) changes were measured in response to duodenal perfusion (0.05 ml/min for 10 min) of an increasing dose of Gly-Sar, a hydrolysis-resistant dipeptide and known PepT1-transportable substrate (11), followed by 8% meat peptone. A 10-min saline flush was given between each treatment. The phasic IGP, or amplitude of the contraction waves, was measured as the mean decrease in height over 2 min of perfusion treatment. The baseline, or tonic, IGP was taken as the average nadir of the trace over the same time period compared with a saline baseline. Differences between the Gly-Sar dose response were compared using a one-way ANOVA and post hoc Dunnett's test against the saline control. Significance was accepted at P < 0.05.

Data Analysis and Statistics

All values are expressed as means ± SE, unless otherwise stated. Significance for PepT1 gene expression among the cell lines and between CCK-eGFP and non-eGFP cells was determined using a one-way ANOVA and a Student's t-test of the ΔCT values, respectively. ERK1/2 signaling responses were normalized to no treatment (EBSS) and represented as a fold change from 1.0. Significance among the treatments was determined using a one-way ANOVA and post hoc Dunnett's test.

For hormone secretion studies in CCK-eGFP cells, values were expressed as the percent change from baseline secretion, and significance was determined using a one-way ANOVA and appropriate post hoc test. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 5. Significance was accepted at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

STC-1 Cells Functionally Express PepT1

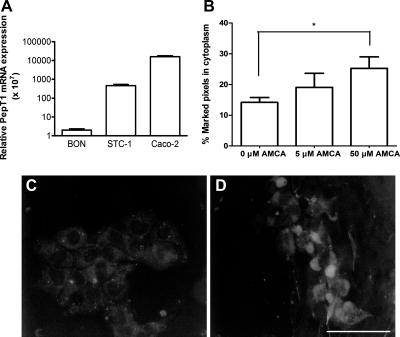

To determine whether STC-1 cells have the potential to express functional PepT1, quantitative RT-PCR was performed. PepT1 mRNA expression was compared between the murine CCK-secreting STC-1 cell line (n = 3), the human serotonin-secreting BON cell line (n = 3), and the human intestinal epithelial Caco-2 cell line (n = 4) relative to GAPDH. STC-1 cells expressed less PepT1 transcript than the Caco-2 cell and at least 220-fold more PepT1 transcript level than the BON cell, which was rarely detectable (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

A: proton-coupled oligopeptide transporter (PepT1) gene expression in STC-1 cells (n = 3), BON cells (n = 3; negative control), and Caco-2 cells (n = 4; positive control) relative to GAPDH. B: dose-dependent AMCA-labeled uptake in STC-1 cells, expressed as %fluorescently marked cytoplasmic pixels, demonstrating functional expression of the PepT1 transporter. *P < 0.05 compared with no treatment. C and D: representative images of AMCA-labeled peptide uptake by STC-1 cells at 10 μm (C) and 50 μm (D).

To demonstrate functional evidence for PepT1 in the STC-1 cell line, the ability to transport AMCA-labeled peptide (13) was determined by analyzing fluorescent peptide uptake under epifluorescent microscopy and quantifying the percent of illuminated pixels from total pixels within the cell cytoplasm. A dose-dependent increase in cytoplasmic AMCA-labeled peptide was observed, starting from 14 ± 1.6% pixels (n = 21) at 0 μM AMCA, 19 ± 4.6% pixels (n = 9) at 5 μM AMCA, and to 25 ± 3.8% pixels (n = 12) at 50 μM AMCA, with a significant pixel count compared with baseline (P < 0.05; Fig. 1, B–D).

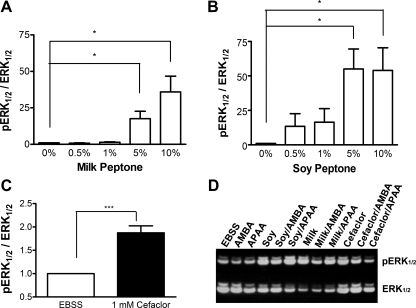

Phosphorylation Activity of the ERK1/2 Pathway in STC-1 Cells in Response to Peptone and Cefaclor

To ensure that STC-1 cells behave similarly to other reported studies, the activation of STC-1 cells was measured in response to peptone and the cephalosporin antibiotic Cefaclor. Activation was measured as the ratio of pERK1/2 over total ERK1/2 (pERK1/2/ERK1/2) in response to treatment, normalized to the pERK1/2/ERK1/2 ratio of EBSS alone (control). STC-1 cells demonstrated dose-responsive activation to both milk and soy peptone (Fig. 2, A and B). Based on the dose-response curves, the 1% soy peptone and 5% milk peptone dosages were used for further studies. Cefaclor significantly increased the pERK/ERK ratio by ∼68 ± 14% compared with EBSS alone (n = 7; P = 0.001; Fig. 2C), similar to that observed by others (27).

Fig. 2.

Activation of STC-1 cells in response to both milk peptone (A) and soy peptone (B) and to Cefaclor (C). A 2-min exposure of increasing concentrations of both milk (A) and soy peptone (B) causes a dose-dependent increase in phosphorylated ERK1/2 (pERK1/2) relative to total ERK1/2. C: the PepT1-transportable cephalosporin antibiotic Cefaclor (1 mM) also significantly increases ERK1/2 phosphorylation activity. D: representative Western blot image of the effect of the PepT1 agonist 4-aminomethyl benzoic acid (AMBA) or the inactive analog 4-aminophenylacetic acid (APAA) on substrate-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation. pERK1/2 and total ERK1/2 were measured by densitometry and expressed as a ratio of pERK1/2 to ERK1/2. Values were normalized to the control [Earl's balanced salt solution (EBSS) only] and expressed as means ± SE; n = 5–7 separate passages performed in triplicate. Significance was found using a 1-sample t-test against EBSS. *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001 relative to EBSS.

PepT1 Antagonist 4-AMBA Does Not Significantly Attenuate ERK1/2 Phosphorylation in Response to Peptone and Cefaclor

To determine whether PepT1 was required for STC-1 cell activation in response to milk peptone, soy peptone, and Cefaclor, the effect of the commercially available PepT1 inhibitor 4-AMBA on ERK1/2 phosphorylation activation was tested and compared with its inactive analog 4-APAA (n = 3–5). A dose response with 50 μM, 0.5 mM, and 5 mM 4-AMBA with all three substrates was performed, but the effect of 5 mM 4-AMBA against peptone-induced ERK1/2 activation was most consistent. Alone, 4-AMBA and 4-APAA had no endogenous effect on ERK1/2 activation. 4-AMBA or 4-APAA had no effect on pERK1/2 in response to milk peptone, soy peptone, and Cefaclor (Table 1 and Fig. 2D).

Table 1.

Activation of ERK1/2 in response to peptones or Cefaclor in the presence of absence of either the PepT1 competitive inhibitor 4-AMBA (5 mM) or its inactive analog 4-APAA (5 mM)

| Inhibitor or Inactive Analog |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| None | 4-AMBA | 4-APAA | |

| EBSS | 1.0 ± 0.00 | 1.0 ± 0.06 | 1.1 ± 0.10 |

| Soy peptone (1%) | 1.8 ± 0.08*** | 1.6 ± 0.18* | 2.5 ± 0.44** |

| Milk peptone (5%) | 2.5 ± 0.73* | 2.1 ± 0.58* | 2.7 ± 0.87 |

| Cefaclor (1 mM) | 1.3 ± 0.15 | 1.2 ± 0.12* | 1.3 ± 0.42 |

Values are expressed as means ± SE and are represented as a mean fold change over baseline (1.0, solid line); n = 5 separate passages performed in triplicate.

PepT1, proton-coupled oligopeptide transporter; 4-AMBA, 4-aminomethyl benzoic acid; 4-APAA, 4-aminophenylacetic acid.

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01, and

P< 0.001 compared with Earl's balanced salt solution (EBSS).

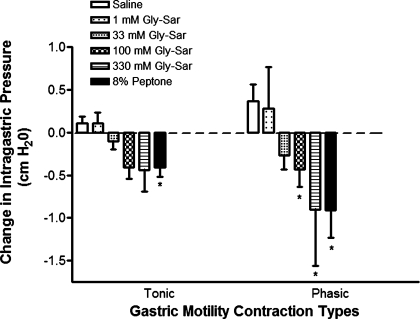

Gly-Sar Inhibits Gastric Motility But Does Not Directly Activate CCK-Secreting Enteroendocrine Cells

Duodenal perfusion of specific PepT1-translocatable synthetic dipeptide, Gly-Sar, caused a dose-dependent inhibition of gastric motility in anesthetized rats, primarily for phasic IGP, similar to that observed with 8% peptone (Fig. 3). To test whether Gly-Sar could directly activate enteroendocrine cell signaling pathways and hormone secretion, STC-1 cells (n = 6) underwent a 2-min exposure to Gly-Sar, which was ineffective at increasing pERK1/2 activity. Additionally, hormone secretion from isolated CCK-eGFP cells (n = 8) was not different from baseline in response to Gly-Sar (see Fig. 5). Together, these findings suggest that Gly-Sar may be inhibiting gastric motility via PepT1 indirectly and not by direct activation of CCK-secreting enteroendocrine cells.

Fig. 3.

The effect of PepT1-transportable peptide glycyl-sarcosine (Gly-Sar) on gastric motility and STC-1 cell activity. Duodenal perfusion with Gly-Sar dose dependently inhibits intraluminal gastric pressure changes in the anesthetized rat. 8% peptone served as a positive control. Values are means ± SE; n = 5–11 experiments per group. *P < 0.05 compared with saline.

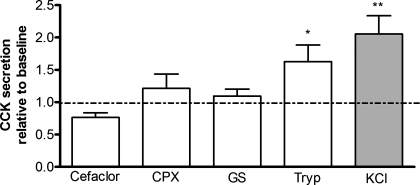

Fig. 5.

CCK secretion in response to various PepT1 substrates in acutely isolated CCK-eGFP cells, indicating a significant increase in CCK secretion in response to tryptone (Tryp, 1%) and KCl (50 mM; positive control; gray bar) but not to the cephalosporin antibiotics Cefaclor (1 mM; n = 2) and cephalexin (CPX, 20 mM) or to the synthetic PepT1-transportable dipeptide Gly-Sar (GS, 1 mM). Values are normalized to the vehicle control (baseline set as 1.0) and expressed as means ± SE. For all treatments, except Cefaclor, n = 5–7 separate cell preparations performed in triplicate wells and assayed in triplicate with a radioimmunoassay. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

Endogenous PepT1 Expressed in Acutely Isolated Native Murine CCK-eGFP Cells Does Not Mediate CCK Secretion in Response to PepT1 Specific Ligands

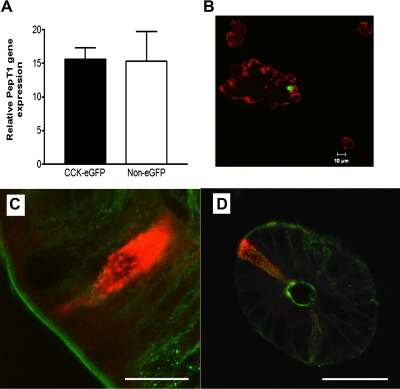

Isolated CCK-eGFP cells express PepT1 at a gene and protein level similar to that of the sorted non-eGFP cell population (Fig. 4, A and B), which supports immunohistochemical staining of PepT1 closely aligned to CCK-immunoreactive cells in rat frozen tissue sections (Fig. 4C). In the absence of primary antibodies, no nonspecific immunofluorescent staining was apparent (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

PepT1 is expressed in native intestinal I cells. A: murine cells with cholecystokinin promoter-driven enhanced green fluorescent protein (CCK-eGFP) and non-eGFP cells demonstrate equivalent PepT1 gene expression, relative to β-actin. B: PepT1 protein expression (red) is also apparent in both the CCK-eGFP cell (green) and non-eGFP cells in partially digested intestinal epithelial cell suspensions. Longitudinal (C) and crypt cross sections (D) of rat intestine show PepT1 (green) expression along the brush-border membrane with colocalization at the apical membrane of CCK-immunoreactive endocrine cells (red). Scale bars: C, 10 μm; D, 50 μm.

To evaluate hormone secretion activity in response to PepT1-transportable substrates, acutely isolated CCK-eGFP cells were exposed to various PepT1 substrates such as increasing concentrations of the dipeptide Phe-Ala, the hydrolysis-resistant Gly-Sar, and cephalosporin antibiotics Cefaclor and cephalexin, and CCK was measured from the supernatant by radioimmunoassay. Phe-Ala, a known high-affinity PepT1-transportable substrate in transfected cells (40), did not significantly increase CCK secretion in acutely isolated murine I cells (n = 3–4, data not shown). Neither were Cefaclor and cephalexin effective at increasing CCK secretion compared with baseline (Fig. 5). The enzymatic casein digest tryptone evoked a more consistently robust increase in CCK secretion compared with baseline (P < 0.05). A similar response was observed with a meat peptone source (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we investigated the role of the oligopeptide transporter PepT1 as a putative protein hydrolysate sensor directly mediating signaling pathways and hormone secretion from CCK-secreting enteroendocrine cells. Although PepT1 is expressed in both the STC-1 cell line and in acutely isolated native CCK-eGFP cells, cellular activity is not affected by either PepT1 inhibitors or specific PepT1-transportable substrates. However, PepT1-transportable substrate is an effective inhibitor of gastric motility. Therefore, the data suggest that PepT1 indirectly, but not directly, regulates CCK secretion in response to protein hydrolysates.

Previous studies in anesthetized rats indirectly supported a role for PepT1 on CCK1 receptor-sensitive vagal afferent neuronal activation and gastric motility in response to protein hydrolysates (6), suggesting that PepT1 mediates CCK secretion from I cells. A more specific PepT1 substrate, Cefaclor, has also been shown to cause a delay in gastric emptying through activation of a CCK1-mediated vagal afferent pathway (2, 6). The current study demonstrates that Gly-Sar, a hydrolysis-resistant synthetic dipeptide often used for PepT1-transport kinetic studies in intestinal epithelial cell lines (39), causes a dose-dependent inhibition of gastric motility in anesthetized rats. Therefore, current in vivo studies support a role for PepT1 on influencing CCK-associated functions.

Given that PepT1 is expressed along the intestinal brush-border membrane of absorptive epithelial cells (17, 29, 41) and Caco-2 cells (16), we aimed to evaluate whether PepT1 directly transduces signals on the endocrine cells or whether its effect is indirect through signals originating from other cell types. PepT1 mRNA is detectable in both the STC-1 cell line and in acutely isolated CCK-eGFP cells, and double immmunofluorescent staining for both PepT1 and CCK in rat tissue sections and in partially digested CCK-eGFP mouse mucosa is suggestive that these cells express this transporter. Furthermore, AMCA-labeled peptide is dose-dependently transported into the STC-1 cell, suggesting that PepT1 may, indeed, be functionally expressed by these cells.

To evaluate whether the effect of PepT1 on activation of CCK-secreting enteroendocrine cells is direct or indirect, we examined both the STC-1 cell line and acutely isolated native CCK-eGFP cells. Protein hydrolysates and cephalosporin antibiotics are known to activate STC-1 cells and elicit CCK secretion (27–28). We demonstrated similar activation in our cells by measuring ERK1/2 phosphorylation activity in response to the same substrates. However, although the PepT1 inhibitor 4-AMBA significantly reduced the effect of peptone on vagal afferent activation and gastric motility (6), it did not significantly reduce ERK1/2 phosphorylation in the STC-1 cell in response to peptone and Cefaclor. Furthermore, the PepT1 specific substrates had no effect on activation of STC-1 cells or eliciting CCK secretion from isolated CCK-eGFP cells, even though PepT1 specific dipeptide Gly-Sar had a significant effect on inhibiting gastric motility. Taken together, the data suggest that PepT1 is not directly involved in mediating enteroendocrine cell activation in response to peptone, which contradicts what has been reported by others (23). There remains the possibility, however, that PepT1 plays an indirect role in activating CCK1 receptor-mediated vagal afferent signaling and its downstream effects on gastric motor function.

Given that protein hydrolysates consistently activate and elicit hormone secretion from STC-1 cells and native CCK-eGFP cells, it is apparent that another protein sensor is expressed by these cells. The G protein-coupled receptor GPR93, which also utilizes the ERK1/2 pathways, has been implicated in peptone sensing by the STC-1 cell (3). Whether GPR93 or another, still unidentified protein sensor is functionally expressed by the enteroendocrine I cell remains to be elucidated.

Protein detection by the intestinal I cell likely incorporates both indirect and direct detection mechanisms. Although PepT1 is expressed by CCK-secreting enteroendocrine cells, the evidence does not support its role in directly mediating protein hydrolysate-induced hormone secretion. Given its influence on gastric motility, perhaps the transport of peptides via PepT1 by the enterocyte may initiate secretion of signaling factors that stimulate the I cell to secrete CCK. This signaling factor may be diazepam-binding inhibitor (DBI), a CCK-releasing peptide originally isolated in the rat intestinal mucosa that has been demonstrated to elicit pancreatic secretion and elevate plasma CCK levels in the rat (20) and elicit CCK secretion by the STC-1 cell (44). It would be interesting to test whether a connection exists between PepT1-transporter activity and DBI secretion by the intestinal mucosa in CCK secretion.

GRANTS

This work was funded by grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK-41004), the California Dairy Research Foundation, and the Dairy Marketing Initiative.

DISCLOSURES

Dr. S. Hao is currently working for Ajinomoto, a company that has an interest in protein, amino acids, and health. However, she was only involved in this project when she was employed by UC Davis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to J. R. Reeve (University of California Los Angeles) for providing reagents and Susanne Pechhold, Xinping Lu, and Xilin Zhao (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases) for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bensaid A, Tome D, Gietzen D, Even P, Morens C, Gausseres N, Fromentin G. Protein is more potent than carbohydrate for reducing appetite in rats. Physiol Behav 75: 577–582, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bozkurt A, Deniz M, Yegen BC. Cefaclor, a cephalosporin antibiotic, delays gastric emptying rate by a CCK-A receptor-mediated mechanism in the rat. Br J Pharmacol 131: 399–404, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Choi S, Lee M, Shiu AL, Yo SJ, Hallden G, Aponte GW. GPR93 activation by protein hydrolysate induces CCK transcription and secretion in STC-1 cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 292: G1366–G1375, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Conigrave AD, Brown EM. Taste receptors in the gastrointestinal tract. II L-amino acid sensing by calcium-sensing receptors: implications for GI physiology. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 291: G753–G761, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cordier-Bussat M, Bernard C, Haouche S, Roche C, Abello J, Chayvialle JA, Cuber JC. Peptones stimulate cholecystokinin secretion and gene transcription in the intestinal cell line STC-1. Endocrinology 138: 1137–1144, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Darcel NP, Liou AP, Tome D, Raybould HE. Activation of vagal afferents in the rat duodenum by protein digests requires PepT1. J Nutr 135: 1491–1495, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Eastwood C, Maubach K, Kirkup AJ, Grundy D. The role of endogenous cholecystokinin in the sensory transduction of luminal nutrient signals in the rat jejunum. Neurosci Lett 254: 145–148, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fei YJ, Kanai Y, Nussberger S, Ganapathy V, Leibach FH, Romero MF, Singh SK, Boron WF, Hediger MA. Expression cloning of a mammalian proton-coupled oligopeptide transporter. Nature 368: 563–566, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Forster ER, Green T, Elliot M, Bremner A, Dockray GJ. Gastric emptying in rats: role of afferent neurons and cholecystokinin. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 258: G552–G556, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Freeman SL, Bohan D, Darcel N, Raybould HE. Luminal glucose sensing in the rat intestine has characteristics of a sodium-glucose cotransporter. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 291: G439–G445, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ganapathy V, Burckhardt G, Leibach FH. Characteristics of glycylsarcosine transport in rabbit intestinal brush-border membrane vesicles. J Biol Chem 259: 8954–8959, 1984 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gevrey JC, Cordier-Bussat M, Nemoz-Gaillard E, Chayvialle JA, Abello J. Co-requirement of cyclic AMP- and calcium-dependent protein kinases for transcriptional activation of cholecystokinin gene by protein hydrolysates. J Biol Chem 277: 22407–22413, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Groneberg DA, Doring F, Eynott PR, Fischer A, Daniel H. Intestinal peptide transport: ex vivo uptake studies and localization of peptide carrier PEPT1. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 281: G697–G704, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guan D, Green GM. Significance of peptic digestion in rat pancreatic secretory response to dietary protein. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 271: G42–G47, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hirasawa A, Tsumaya K, Awaji T, Katsuma S, Adachi T, Yamada M, Sugimoto Y, Miyazaki S, Tsujimoto G. Free fatty acids regulate gut incretin glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion through GPR120. Nat Med 11: 90–94, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hsu CP, Walter E, Merkle HP, Rothen-Rutishauser B, Wunderli-Allenspach H, Hilfinger JM, Amidon GL. Function and immunolocalization of overexpressed human intestinal H+/peptide cotransporter in adenovirus-transduced Caco-2 cells (Abstract). AAPS PharmSci 1: E12, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hussain I, Kellett L, Affleck J, Shepherd J, Boyd R. Expression and cellular distribution during development of the peptide transporter (PepT1) in the small intestinal epithelium of the rat. Cell Tissue Res 307: 139–142, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ivy AC, Oldberg E. A hormone mechanism for gall-bladder contraction and evacuation. Am J Physiol 86: 559–613, 1928 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jang HJ, Kokrashvili Z, Theodorakis MJ, Carlson OD, Kim BJ, Zhou J, Kim HH, Xu X, Chan SL, Juhaszova M, Bernier M, Mosinger B, Margolskee RF, Egan JM. Gut-expressed gustducin and taste receptors regulate secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 15069–15074, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li Y, Hao Y, Owyang C. Diazepam-binding inhibitor mediates feedback regulation of pancreatic secretion and postprandial release of cholecystokinin. J Clin Invest 105: 351–359, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li Y, Owyang C. Endogenous cholecystokinin stimulates pancreatic enzyme secretion via vagal afferent pathway in rats. Gastroenterology 107: 525–531, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liou AP, Lu X, Sei Y, Zhao X, Pechhold S, Carrero RJ, Raybould HE, Wank S. The G protein-coupled receptor GPR40 directly mediates long chain fatty acid-induced secretion of cholecystokinin. Gastroenterology In press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Matsumura K, Miki T, Jhomori T, Gonoi T, Seino S. Possible role of PEPT1 in gastrointestinal hormone secretion. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 336: 1028–1032, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Meredith D, Boyd CA, Bronk JR, Bailey PD, Morgan KM, Collier ID, Temple CS. 4-aminomethylbenzoic acid is a non-translocated competitive inhibitor of the epithelial peptide transporter PepT1. J Physiol 512: 629–634, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Meredith D, Price RA. Molecular modeling of PepT1-towards a structure. J Membr Biol 213: 79–88, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Moriya R, Shirakura T, Ito J, Mashiko S, Seo T. Activation of sodium-glucose cotransporter 1 ameliorates hyperglycemia by mediating incretin secretion in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 297: E1358–E1365, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Murai A, Noble PM, Deavall DG, Dockray GJ. Control of c-fos expression in STC-1 cells by peptidomimetic stimuli. Eur J Pharmacol 394: 27–34, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nemoz-Gaillard E, Bernard C, Abello J, Cordier-Bussat M, Chayvialle JA, Cuber JC. Regulation of cholecystokinin secretion by peptones and peptidomimetic antibiotics in STC-1 cells. Endocrinology 139: 932–938, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ogihara H, Saito H, Shin BC, Terado T, Takenoshita S, Nagamachi Y, Inui K, Takata K. Immuno-localization of H+/peptide cotransporter in rat digestive tract. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 220: 848–852, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Parker HE, Habib AM, Rogers GJ, Gribble FM, Reimann F. Nutrient-dependent secretion of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide from primary murine K cells. Diabetologia 52: 289–298, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Raybould HE, Tache Y. Cholecystokinin inhibits gastric motility and emptying via a capsaicin-sensitive vagal pathway in rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 255: G242–G246, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Raybould HE, Zittel TT, Holzer HH, Lloyd KC, Meyer JH. Gastroduodenal sensory mechanisms and CCK in inhibition of gastric emptying in response to a meal. Dig Dis Sci 39: 41S–43S, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Reimann F, Habib AM, Tolhurst G, Parker HE, Rogers GJ, Gribble FM. Glucose sensing in L cells: a primary cell study. Cell Metab 8: 532–539, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shi G, Leray V, Scarpignato C, Bentouimou N, Bruley des Varannes S, Cherbut C, Galmiche JP. Specific adaptation of gastric emptying to diets with differing protein content in the rat: is endogenous cholecystokinin implicated? Gut 41: 612–618, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Takahashi T, Owyang C. Mechanism of cholecystokinin-induced relaxation of the rat stomach. J Auton Nerv Sys 75: 123–130, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tanaka T, Katsuma S, Adachi T, Koshimizu TA, Hirasawa A, Tsujimoto G. Free fatty acids induce cholecystokinin secretion through GPR120. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 377: 523–527, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Temple CS, Stewart AK, Meredith D, Lister NA, Morgan KM, Collier ID, Vaughan-Jones RD, Boyd CA, Bailey PD, Bronk JR. Peptide mimics as substrates for the intestinal peptide transporter. J Biol Chem 273: 20–22, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Theodorakis MJ, Carlson O, Michopoulos S, Doyle ME, Juhaszova M, Petraki K, Egan JM. Human duodenal enteroendocrine cells: source of both incretin peptides, GLP-1 and GIP. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 290: E550–E559, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Thwaites DT, Brown CD, Hirst BH, Simmons NL. Transepithelial glycylsarcosine transport in intestinal Caco-2 cells mediated by expression of H(+)-coupled carriers at both apical and basal membranes. J Biol Chem 268: 7640–7642, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vig BS, Stouch TR, Timoszyk JK, Quan Y, Wall DA, Smith RL, Faria TN. Human PEPT1 pharmacophore distinguishes between dipeptide transport and binding. J Med Chem 49: 3636–3644, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Walker D, Thwaites DT, Simmons NL, Gilbert HJ, Hirst BH. Substrate upregulation of the human small intestinal peptide transporter, hPepT1. J Physiol 507: 697–706, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wang SY, Chi MM, Li L, Moley KH, Wice BM. Studies with GIP/Ins cells indicate secretion by gut K cells is KATP channel independent. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 284: E988–E1000, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. White WO, Schwartz GJ, Moran TH. Role of endogenous CCK in the inhibition of gastric emptying by peptone and Intralipid in rats. Regul Pept 88: 47–53, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yoshida H, Tsunoda Y, Owyang C. Diazepam-binding inhibitor33–50 elicits Ca2+ oscillation and CCK secretion in STC-1 cells via L-type Ca2+ channels. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 276: G694–G702, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]