Abstract

Dlx transcription factors are important in the differentiation of GABAergic interneurons. In mice lacking Dlx1, early steps in interneuron development appear normal. Beginning at ∼1 mo of age, primarily dendrite-innervating interneuron subtypes begin to undergo apoptosis in Dlx1−/− mice; this is accompanied by a reduction in GABAergic transmission and late-onset epilepsy. The reported reduction of synaptic inhibition is greater than might be expected given that interneuron loss is relatively modest in Dlx1−/− mice. Here we report that voltage-clamp recordings of CA1 interneurons in hippocampal slices prepared from Dlx1−/− animals older than postnatal day 30 (>P30) revealed a significant reduction in excitatory postsynaptic current (EPSC) amplitude. No changes in EPSCs onto interneurons were observed in cells recorded from younger animals (P9–12). Current-clamp recordings from interneurons at these early postnatal ages showed that interneurons in Dlx1−/− mutants were immature and more excitable, although membrane properties normalized by P30. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP-mediated nick-end labeling, caspase-3, and NeuN staining did not reveal frank cell damage or loss in area CA3 of hippocampal sections from adult Dlx1−/− mice. Delayed interneuron maturation may lead to interneuron hyperexcitability, followed by a compensatory reduction in the strength of excitatory transmission onto interneurons. This reduced excitation onto surviving interneurons, coupled with the loss of a significant fraction of GABAergic inputs to excitatory neurons starting at P30, may underlie cortical dysrhythmia and seizures previously observed in adult Dlx1−/− mice.

Keywords: excitatory postsynaptic currents, CA1, CA3, γ-aminobutyric acid

the mechanisms leading to generation of spontaneous epileptic seizures have been the focus of intense study for nearly 100 years. Although many possible mechanisms have emerged, impairment of GABA-mediated inhibition is likely a critical cause of seizure activity in many forms of epilepsy. Several observations support this suggestion. First, subpopulations of GABAergic interneurons are vulnerable to seizure-induced damage in experimental models of epilepsy and humans with temporal lobe epilepsy (de Lanerolle et al. 1989, 2003). Second, altered inhibitory drive has been reported in animal models of cortical malformation and epilepsy (Zhu and Roper 2000; Trotter et al. 2006; Jones and Baraban 2007; Jones and Baraban 2009). Third, epilepsy-associated changes in the expression and function of postsynaptic GABAA receptors are commonly observed (Brooks-Kayal et al. 1998; Loup et al. 2000; Coulter 2000; Crino et al. 2001). Fourth, changes in the function and expression of GABA reuptake transporters have been described in neurons in an animal model of epilepsy (Calcagnotto et al. 2002). Fifth, reductions in action potential number, frequency, and amplitude were observed in cultured hippocampal interneurons (but not pyramidal cells) from a mouse model of severe myoclonic epilepsy in childhood (Yu et al. 2006).

These results provide strong support for the conclusion that reduced GABA signaling plays a central role in epilepsy and seizure generation. However, this is largely based on data from chemoconvulsant models of acquired epilepsy and in utero (or early postnatal) injury in normal rodents or examination of tissue samples from patients with medically intractable epilepsy. Recent observations from genetically altered mice based on manipulation of factors necessary for interneuron development demonstrate that selective interneuron reduction (i.e., “interneuronopathy”) can lead to reduced inhibition, spontaneous recurrent seizures, or both (Powell et al. 2003; Cobos et al. 2005; Marsh et al. 2009). Homozygous Dlx1 mutant mice (Dlx1−/−) have an age-dependent loss of ∼50% of calretinin (CR), 35% of neuropeptide Y, and 35% of somatostatin (SOM)-positive interneurons in the hippocampus of young adult animals (Cobos et al. 2005). Analysis of GABA-mediated postsynaptic currents in pyramidal neurons at a postnatal age when interneuron loss and seizures are observed [i.e., older than postal day 30 (P30)] revealed a nearly 50% reduction in inhibition. Given that soma-targeting, basket-type, parvalbumin-positive interneurons are preserved in these mice, and given the relatively modest loss of somatostatin and calretinin-positive interneurons, this reduction in IPSC amplitude and frequency was greater than might be expected.

These findings led us to hypothesize that reduced excitation onto surviving interneurons could further contribute to inhibition loss in Dlx1 knockout mice. To explore this possibility, we analyzed spontaneous and miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (sEPSCs and mEPSCs) onto CA1 interneurons, as well as intrinsic membrane properties of interneurons, in hippocampal slices prepared from wild-type (WT) and Dlx1−/− littermates at two ages: 1) P9-P11, before interneuron death and cell loss; and 2) >P30, after significant interneuron death and reduced synaptic inhibition. Anatomical studies designed to assess cell loss or damage in stratum pyramidale of area CA3 (the primary source of excitatory input to CA1 interneurons) were also performed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Slice preparation.

All animal work and experimental protocols were carried out in accordance with guidelines defined by the relevant national and local animal welfare bodies. All animal work was approved by the University of California, San Francisco, Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Approval Number AN078649-03A). Mice were anesthetized and decapitated, and the brain was quickly removed and placed into oxygenated, ice-cold, high sucrose artificial cerebrospinal fluid (saCSF), containing the following (in mM): 150 sucrose, 50 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 10 dextrose, 2.5 KCl, 1 NaH2PO4-H2O, 0.5 CaCl2, and 7 MgCl2. After 2 min in saCSF, the brain was blocked, glued to the stage of a vibratome (Leica VTS1000, Bannockburn, IL), and cut into 300 μm horizontal brain slices containing hippocampus. Slices were then placed in a holding chamber containing aCSF (in mM; 124 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4-H2O, 2 MgSO4-7H2O, 26 NaHCO3, 10 dextrose, and 2 CaCl2). After a 40-min incubation period at 35°C, slices were maintained at room temperature (6–8 h).

Electrophysiology.

For recording, an individual slice was placed in a submerged recording chamber (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT) with oxygenated aCSF heated to ∼32°C and flowing at 2–4 ml/min. Interneurons were identified in area CA1 under infrared differential interference contrast optics, and were initially distinguished based on soma shape and location outside the principal cell layer. A micropipette puller (Sutter Instrument, Novato, CA) was used to pull patch pipettes of between 3–7 MΩ from 1.5 mm outer diameter borosilicate glass (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL). Data were obtained using an Axopatch 1D amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA); data were digitized at 10 kHz and recorded using a Digidata 1320A and pClamp 8.2 software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). For all experiments except mEPSC recordings, internal recording solution (pH 7.20–7.25, 285–295 mosmol/kgH2O, liquid junction potential −13 mV) contained the following (in mM): 120 K-gluconate, 10 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 0.025 CaCl2, 0.2 EGTA, 2 Na2ATP, 0.2 Na2GTP, and 10 HEPES. In mEPSC experiments, to enhance event amplitude and increase signal-to-noise ratio, internal recording solution contained the following (in mM): 140 CsCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 11 EGTA, 2 Na2ATP, 0.5 Na2GTP, and 1.25 QX-314.

After a stable voltage-clamp recording was obtained from a CA1 interneuron, the recording was switched to current-clamp mode and injected steps of hyperpolarizing and depolarizing current were used to determine the class of cell being recorded using published firing patterns and action potential properties (Butt et al. 2005; Flames and Marin 2005). The recording was subsequently switched back to voltage-clamp mode (holding potential, −60 mV) for recording of sEPSCs or mEPSCs. Membrane potentials were not corrected for liquid junction potential. Spontaneous EPSCs were pharmacologically isolated by perfusion of the slice with aCSF containing 5 μM bicuculline (a GABAA receptor blocker; Sigma, St. Louis, MO). At the end of some experiments, 3 mM kynurenic acid (a nonspecific glutamate receptor antagonist; Tocris, Ellisville, MO) was added to confirm that EPSCs were successfully isolated. All recordings were obtained at ∼32°C. Voltage-clamp recordings were low-pass filtered at 1 kHz, and band-pass filtered at 60 Hz (Hum Bug; AutoMate Scientific, Berkeley, CA). Whole cell access resistance and holding current were continuously monitored to confirm that recordings were stable.

Spontaneous EPSCs were analyzed using Mini Analysis Program 5.2.5 (Synaptosoft, Decatur, GA), with each event selected by hand and 300 events per cell being analyzed. Because of the low frequency of mEPSCs, we analyzed ≥25 events or at least ≥5 min of recording time per cell. Histograms of sEPSCs were constructed using the first 100 events per cell. For decay time calculations, decay time of individual events was defined as the time to 67% of peak amplitude. All data are presented as means ± SE, and we determined statistical significance of results using unpaired, two-tailed Student's t-tests, with P = 0.05 as the threshold for statistical significance. Where appropriate, the χ2 test or ANOVA was used to determine statistical significance.

Histology.

Adult Dlx1−/− and WT littermate mice were deeply anesthetized with Avertin (Sigma; 0.2 ml/10 g body wt) and perfused intracardially with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS solution (0.1 M, pH 7.4). The brains were removed and postfixed overnight in the same fixative. Brain sections were prepared at a thickness of 50 μm on a vibratome and used for free-floating immunohistochemistry or mounted on Fisher Superfrost/Plus slides for the terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase dUTP-mediated nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay. For immunohistochemistry, the slices were washed in phosphate-buffered saline solution, incubated in blocking solution (0.5% Triton X-100, 10% normal goat serum, 2% nonfat milk, and 0.2% gelatin in PBS) for 1 h, and incubated 1 day at 4°C in the primary antibody diluted in 0.5% Triton X-100, 3% normal goat serum, and 0.2% gelatin in PBS. The antibodies used were as follows: cleaved caspase-3 polyclonal antibodies (1:500; Cell Signaling Technology) and NeuN monoclonal antibodies (1:500; Chemicon). Immunoreactivity was detected with appropriate Alexa-488 or Alexa-594 (1:300; Molecular Probes) conjugated secondary antibodies. TUNEL apoptotic cell detection was carried out following the manufacturer's protocol (Apotag Red In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit; Chemicon).

Cell counting.

Quantification of TUNEL+, cleaved caspase-3+, and NeuN+ cells in the CA3 region of the hippocampus was determined in coronal sections from three mice of each genotype. Cell counts were performed on digitized images obtained with a CoolSNAP EZ Turbo 1394 digital camera (Photometric, Tucson, AZ) on a Nikon ECLIPSE 80i microscope (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY) using a ×10 objective. The numbers of positive cells were assessed in a 10,000-μm2 area of the CA3 pyramidal layer of the hippocampus. Statistical differences between experimental groups were determined with the Student's t-test. Results are presented as means ± SE.

RESULTS

Glutamate-mediated excitation of interneurons in Dlx1−/− mice.

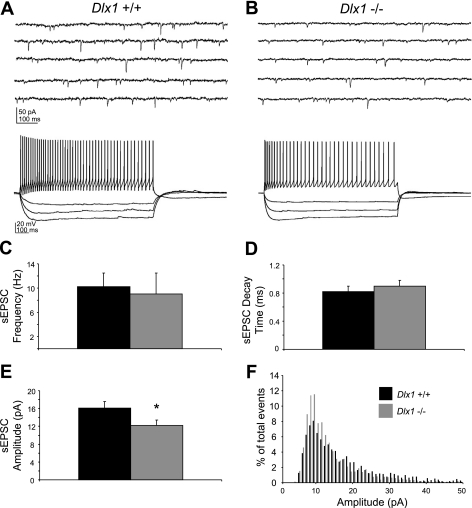

Decreased excitatory input to surviving interneurons in adult Dlx1−/− mice might contribute to the larger-than-expected loss of inhibition previously reported in these animals (Cobos et al. 2005). Here we recorded sEPSCs from 37 visually identified CA1 interneurons in hippocampal slices prepared from >P30 Dlx1−/− mice and WT littermates (Fig. 1). Spontaneous EPSCs are mediated by glutamatergic input to these cells and are abolished by application of 3 mM kynurenic acid, a glutamate receptor antagonist (data not shown). For all sEPSC experiments, we obtained voltage-clamp recordings at a holding potential of −60 mV; representative sEPSC recordings for both genotypes are shown in Fig. 1, A and B, top traces. Following sEPSC data collection, cells were analyzed in current-clamp mode for classification as interneurons; sample current-clamp traces (Fig. 1, A and B, bottom traces) are from the same neuron as voltage-clamp traces. In the “surviving” interneuron population, mean sEPSC amplitude was reduced by ∼25% in Dlx1−/− mutants compared with age-matched littermate controls (WT: 16.87 ± 1.45 pA; Dlx1−/−: 12.80 ± 1.18 pA; P < 0.05; Fig. 1E). Other sEPSC parameters, including frequency (WT: 11.35 ± 2.23 Hz; Dlx1−/−: 10.77 ± 3.46 Hz; P = 0.89; Fig. 1C) and decay times (WT: 0.86 ± 0.08 ms; Dlx1−/−: 0.94 ± 0.08 ms; P = 0.49; Fig. 1D), were unchanged. Construction of an amplitude histogram showed that small-amplitude events predominated in mice lacking Dlx1, while in WT mice, large-amplitude events were more frequent (Fig. 1F). In an additional set of mEPSC recordings from 27 interneurons in >P30 Dlx1−/− mice and WT littermates, mean mEPSC amplitude was significantly reduced in mice lacking Dlx1 (WT: 21.07 ± 0.83 pA; Dlx1−/−: 17.79 ± 1.18 pA; P < 0.03), while no significant differences were observed in mEPSC frequency or decay kinetics (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Excitatory drive of interneurons is decreased in older than postnatal day 30 (P30) Dlx1−/− mice. A, top trace: representative voltage-clamp recording from a wild-type (WT) regular-spiking nonpyramidal (RSNP) interneuron showing spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic current (sEPSCs) (downward deflections). Bottom trace: the same cell recorded in current-clamp mode, confirming its identity as a RSNP interneuron. B, top trace: representative sEPSC recording from a Dlx1−/− RSNP interneuron demonstrating reduced excitatory input. Bottom trace: the same cell recorded in current-clamp mode. C: mean sEPSC frequency is comparable between WT and Dlx1−/− mice. D: sEPSC decay time is also comparable. E: sEPSC amplitude is significantly decreased (P < 0.05, Student's t-test) in Dlx1−/− mice compared with WT mice. F: amplitude histogram of sEPSCs shows a shift toward smaller events in Dlx1−/− mice. Black bars, WT; gray bars, Dlx1−/−.

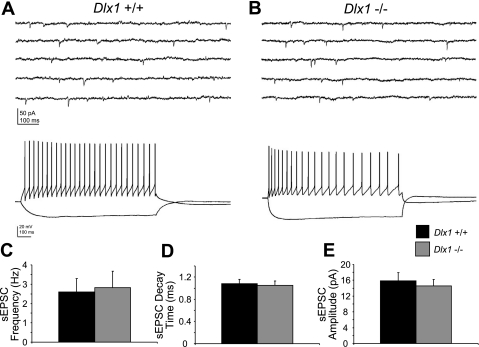

These results raised the question of whether or not reduced excitatory postsynaptic current onto interneurons in Dlx1−/− mice would also be present at ages before interneuron subpopulations began to undergo apoptosis. Interneurons in mice lacking Dlx1 could receive less excitation throughout development, or the decreased EPSC amplitude in Dlx1−/− mice could reflect remodeling of neural circuits that takes place at later ages. To shed light on this question, we recorded sEPSCs from 46 visually identified CA1 interneurons in P9–12 WT and Dlx1−/− mice. Again, sample voltage-clamp recordings of EPSCs and current-clamp recordings of firing properties are shown for each genotype (Fig. 2). At this early postnatal age, we observed no significant differences in sEPSC amplitude (WT: 16.89 ± 2.01 pA; Dlx1−/−: 15.35 ± 1.57 pA; P = 0.55; Fig. 2E), frequency (WT: 2.94 ± 0.69 Hz; Dlx1−/−: 3.25 ± 0.81 Hz; P = 0.77; Fig. 2C), or decay time (WT: 1.12 ± 0.08 ms; Dlx1−/−: 1.09 ± 0.07 ms; P = 0.78; Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Excitatory drive of interneurons is normal in P9–12 Dlx1−/− mice. A, top trace: representative voltage-clamp recording from a WT RSNP interneuron. Bottom trace: the same cell recorded in current-clamp mode, confirming its identity as a RSNP interneuron. B, top trace: representative sEPSC recording from a Dlx1−/− RSNP interneuron. Bottom trace: the same cell recorded in current-clamp mode. C: recordings of sEPSCs in P9–12 WT and Dlx1−/− interneurons show that mean sEPSC frequency is unchanged in young Dlx1 mutant mice. D: mean sEPSC decay time is also similar between WT and mutant mice. E: mean sEPSC amplitude is unchanged. Black bars, WT; gray bars, Dlx1−/−.

Interneuron firing properties in immature Dlx1 knockout mice.

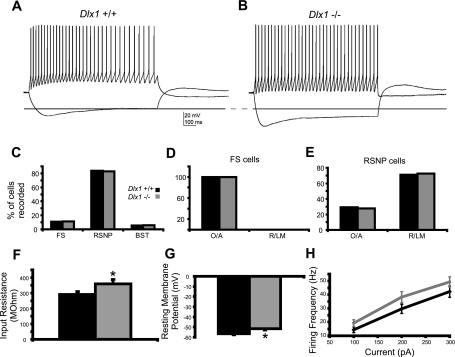

Interneuron numbers, as quantified using immunohistochemical approaches, appear normal in Dlx1−/− mice during the first three postnatal weeks (Cobos et al. 2005). However, it remains unclear whether loss of Dlx1 leads to alterations in interneuron function at younger ages. To determine whether interneurons in early postnatal Dlx1−/− mice exhibit normal membrane properties, we obtained current-clamp recordings in area CA1 (WT: n = 37; Dlx1−/−: n = 35) interneurons. We injected steps of depolarizing and hyperpolarizing current to classify interneurons by firing properties as follows: fast-spiking (FS), regular-spiking nonpyramidal (RSNP), and burst-spiking (BST). We also used these recordings to determine spike width, input resistance (Rin), resting membrane potential (Vm), and fast after hyperpolarization amplitude for each interneuron. A combination of these firing property parameters and laminar location was used to classify interneurons into previously described sub-populations (Butt et al. 2005).

The relative proportions of interneuron subtypes that could be sampled with a patch-clamp recording electrode, which is largely limited to a relatively small population of cells near the surface in an acute slice preparation, were comparable between slices from WT and Dlx1−/− mice at P9–12 (Fig. 3C). Based on our criteria, in WT controls, 11% of interneurons recorded were classified as FS cells (n = 4), 84% were RSNP cells (n = 31), and 5% were BST cells (n = 2). In Dlx1 mutants, 11% of interneurons recorded were classified as FS cells (n = 4), 83% were RSNP cells (n = 29), and 6% were BST cells (n = 2). We also found that the laminar distributions of interneuron cell bodies were comparable between WT and Dlx1 knockout mice at this age (Fig. 3, D and E). All FS cells in WT and knockout mice were located in stratum oriens and alveus (O/A). In addition, most RSNP interneurons were located in stratum radiatum and stratum lacunosum-moleculare (R/LM; WT: 29% in O/A, 71% in R/LM; Dlx1−/−: 28% in O/A, 72% in R/LM). We did not encounter sufficient numbers of BST interneurons to make a valid comparison of their distribution across hippocampal layers.

Fig. 3.

Young Dlx1−/− interneurons exhibit immature membrane properties compared with young WT interneurons. A: sample current-clamp recording from a WT RSNP interneuron. B: sample trace from a Dlx1−/− RSNP interneuron. Note increased input resistance (dashed line). C: overall proportions of interneuron subtypes encountered were comparable between WT and mutant mice. D: in both WT and Dlx1−/− mice, all FS cells were found in stratum oriens/alveus (O/A). E: in both WT and Dlx1−/− mice, most RSNP cells were recorded in stratum radiatum and stratum lacunosum-moleculare (R/LM). F: Input resistance is significantly increased in interneurons recorded form Dlx1 knockout mice (P < 0.05, Student's t-test). G: resting membrane potential is significantly depolarized in Dlx1−/− interneurons (P < 0.05, Student's t-test). H: plot of firing frequency vs. current showing that interneurons from Dlx1−/− mice fire at modestly higher rates in response to a given step size, compared with WT interneurons (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA). Black bars, WT; gray bars, Dlx1−/−.

Interestingly, in these recordings, we found that interneurons in slices from Dlx1−/− mice (P9–12) exhibited what would be considered immature intrinsic membrane properties (Fig. 3, A and B, and Table 1) (Okaty et al. 2009). Specifically, in Dlx1 mutants, interneurons exhibit a high input resistance, as evident in the hyperpolarizing steps shown in Fig. 3, A and B. High input resistance suggests that interneurons lacking Dlx1 are functionally immature compared with age-matched WT interneurons (Fig. 3F; WT Rin: 291.35 ± 18.13 MΩ; Dlx1−/− Rin: 359.16 ± 27.99 MΩ; P < 0.05). Consistent with functional immaturity, interneurons at this age also exhibit a depolarized resting membrane potential (Fig. 3G; WT Vm: −56.6 ± 1.0 mV; Dlx1−/− Vm: −51.6 ± 1.3 mV; P < 0.05). Evaluation of action potential width and other standard parameters failed to uncover additional differences between WT and Dlx1−/− interneurons (Table 1). We also sorted these data by interneuron subtype and found that, in Dlx1−/− RSNP cells, Vm was significantly depolarized (WT Vm: −55.9 ± 1.0 mV; Dlx1−/− Vm: −51.8 ± 1.4 mV; P < 0.03). Finally, we generated a plot of firing frequency vs. current step size to examine excitability of interneurons; to ensure that similar populations of cells were being compared across genotypes, we limited this analysis to RSNP interneurons located in R/LM. We found that interneurons lacking Dlx1 exhibited higher firing rates in response to a given current injection than did WT interneurons (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA; Fig. 3H), consistent with the hypothesis that interneurons in early postnatal mice lacking Dlx1 are hyperexcitable.

Table 1.

Dlx1 knockout interneurons are functionally immature at P9–12

| FF (2×T) | Rin | fAHP1 | AP Width | Vm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 15.08 ± 1.69 | 291.35 ± 18.13 | 19.50 ± 0.81 | 1.54 ± 0.04 | −56.59 ± 0.95 |

| Dlx1 knockout | 19.51 ± 2.02 | 359.16 ± 27.99* | 21.62 ± 1.28 | 1.67 ± 0.08 | −51.57 ± 1.25* |

Shown are mean values ± SE for firing frequency (FF) at twice the firing threshold (2×T), input resistance (Rin), amplitude of fast after hyperpolarization (fAHP1), action potential (AP) width, and resting membrane potential (Vm). Recordings were obtained from hippocampal CA1 interneurons in postnatal days 9–12 (P9–12) wild-type (WT) and mutant mice.

P < 0.05, Student's t-test.

Interneuron function in adult Dlx1 knockout mice.

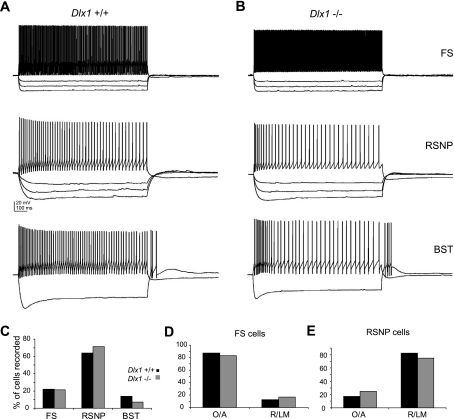

We repeated these current-clamp experiments in mice older than P30 (Fig. 4), when significant interneuron loss was observed in the SOM- and CR-expressing subpopulations of Dlx1−/− mice (Cobos et al. 2005). At this age, interneuron input resistance was comparable between WT and Dlx1−/− mice (WT Rin: 187.44 ± 13.25 MΩ; Dlx1−/− Rin: 212.34 ± 16.47 MΩ; P = 0.24), as was resting membrane potential (WT Vm: −58.5 ± 1.2 mV; Dlx1−/− Vm: −56.8 ± 1.4 mV; P = 0.35). All other membrane and firing properties were also normal in interneurons from Dlx1 mutant mice at >P30 (Table 2). Sorting interneurons by subtype also failed to reveal differences in intrinsic properties at this age (data not shown). The overall laminar distribution of the surviving interneuron subtypes was similar between WT and knockout animals at this age (Fig. 4, D and E). FS cells were primarily located in O/A in both WT and knockout animals (WT: 87.5% in O/A, 12.5% in R/LM; Dlx1−/−: 83% in OA, 17% in R/LM); in addition, most RSNP cells were located in R/LM in both WT and knockout animals (WT: 17% in O/A, 83% in R/LM; Dlx1−/−: 25% in O/A, 75% in R/LM). Although the overall proportions of interneurons subtypes encountered were largely comparable between WT and knockout animals, the proportion of BST interneurons encountered in Dlx1−/− mice (7%) was one-half of the proportion observed in WT mice (14%; Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Adult Dlx1−/− interneurons are indistinguishable from WT interneurons. A: sample traces from WT fast-spiking (FS), RSNP, and burst-spiking (BST) interneurons. B: sample traces from Dlx1−/− FS, RSNP, and BST interneurons, showing that Dlx1−/− interneurons older than P30 exhibit normal membrane properties. C: proportion of BST interneurons recorded in Dlx1−/− mice was approximately half of the proportion observed in WT mice (WT: 14% of interneurons recorded were BST cells; Dlx1−/−: 7% were BST cells). D: FS cells showed a normal laminar location profile in Dlx1−/− mice. E: RSNP cells are also show a normal laminar distribution in Dlx1−/− mice. Black bars, WT; gray bars, Dlx1−/−.

Table 2.

Dlx1 knockout interneurons at >P30 exhibit normal membrane and firing properties

| FF (2×T) | Rin | fAHP1 | AP Width | Vm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 43.08 ± 8.96 | 187.44 ± 13.25 | 25.32 ± 1.55 | 1.05 ± 0.05 | −58.50 ± 1.19 |

| Dlx1 knockout | 43.14 ± 11.11 | 212.34 ± 16.47 | 28.01 ± 1.26 | 1.13 ± 0.07 | −56.79 ± 1.38 |

Shown are mean values ± SE for firing frequency at twice the firing threshold, input resistance, amplitude of fast after hyperpolarization, action potential width, and resting membrane potential. Recordings were obtained from hippocampal CA1 interneurons in >P30 WT and mutant mice.

CA3 pyramidal neurons are unaffected in mice lacking Dlx1.

Cell death or damage to presynaptic CA3 pyramidal neurons, which provide excitatory input to CA1 interneurons, could contribute to the circuit alterations we observed. To exclude this possibility, we performed a series of histology studies on hippocampal sections from adult WT and Dlx1−/− littermates (Fig. 5). We directly assessed apoptosis in Dlx1 mutants by TUNEL staining and cleaved caspase-3 immunohistochemistry. Compared with controls, we observed no change in the numbers of TUNEL+ (Fig. 5, A and B') or activated caspase-3+ (Fig. 5, C and D′) CA3 pyramidal neurons in Dlx1 mutant mice. Furthermore, immunohistochemistry for NeuN, a postmitotic neuronal marker, was used to determine the numbers of neurons within the CA3 pyramidal region of the hippocampus. Quantification revealed no significant differences in the numbers of NeuN+ neurons in WT and Dlx1−/− mice (Fig. 5, E–G).

Fig. 5.

CA3 pyramidal neurons are unaffected in Dlx1 knockout mice. A–D′: no detectable apoptosis is observed in the CA3 pyramidal region of adult control (A–A′ and C–C′) and Dlx1 mutant (B-B′ and D–D') hippocampi as revealed by active caspase-3 antibody (C' and D') and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP-mediated nick-end labeling (A' and B') staining of the corresponding DAPI-labeled (A, B, C, and D) sections. E and F: compared with control (E), no significant change in the number of NeuN+ cells was noticed within the CA3 pyramidal layer of the Dlx1 mutant (F) hippocampus. G: quantification of the number of NeuN+ cells in the CA3 pyramidal layer of the adult hippocampus. Data shown are means ± SE. Scale bar = 250 μm.

DISCUSSION

A homeostatic balance between excitation and inhibition is critical for proper brain function. In adult mice lacking the transcription factor Dlx1, we previously observed apoptotic loss of a subset of the cortical and hippocampal interneuron population, with concomitant reductions in GABA-mediated synaptic transmission, cortical dysrhythmia, and generalized seizures (Cobos et al. 2005). Here we provide additional evidence that Dlx1 may be important in the functional maturation of hippocampal interneurons. We also describe a significant alteration in the excitatory synaptic innervation of surviving interneurons in hippocampal slices from adult Dlx1−/− mice.

Postnatal Dlx1 expression appears to be restricted to dendrite-innervating interneurons (Cobos et al. 2005, 2006); these are the same cells that undergo apoptosis in adult Dlx1−/− mice (Cobos et al. 2005). However, the magnitude and dynamics of the observed change in synaptic inhibition suggest that inhibition from soma-targeting interneurons, which are present in normal numbers, may also be altered (Cobos et al. 2005). Furthermore, interneurons from Dlx1−/− mice show reduced dendrite branching and length (Cobos et al. 2005), suggesting that the dendritic space available for receiving excitatory synapses may be reduced. These lines of evidence led us to hypothesize that surviving interneurons in mice lacking Dlx1 receive reduced excitatory input, contributing to a larger-than-expected loss of inhibition in these animals. Here we report a significant decrease in the amplitude of glutamatergic postsynaptic currents onto surviving interneurons in >P30 mice lacking Dlx1. One functional consequence of Dlx1−/− interneurons receiving less excitation is that these inhibitory cells would be less active, contributing to a larger network reduction in GABA release. This conclusion is consistent with our previous findings (Cobos et al. 2005), a role for reduced inhibition in epilepsy (de Lanerolle et al. 1989; de Lanerolle et al. 2003), and was also reported in a rat model of cortical dysplasia and epilepsy (Xiang et al. 2006). In support of this conclusion, a recent examination of interneuron firing rates in a model of cortical dysplasia reported that reductions in glutamatergic drive of interneurons were correlated with reduced spontaneous firing rates of these cells (Zhou and Roper 2010).

Our results also suggest that a novel circuit rearrangement occurs in adult Dlx1 mutant mice. A reduction in excitation of CA1 interneurons could be explained by a simple reduction in the number of excitatory synapses on surviving interneurons, possibly associated with damage or loss of the presynaptic glutamatergic CA3 pyramidal neurons innervating these cells (Katz 1962; Cormier and Kelly 1996). However, EPSC frequency was unchanged in our recordings and we failed to detect any CA3 cell damage or loss using TUNEL, caspase, or NeuN staining, suggesting that glutamatergic input and release probability are normal (Manabe et al. 1992). The reduced EPSC amplitude that we observed suggests that fewer functional glutamate receptors are present at excitatory synapses onto CA1 interneurons in adult Dlx1 mutant mice. As our recordings were obtained at a holding potential of −60 mV, virtually all EPSCs recorded are likely to be mediated by AMPA receptors. Therefore, our results predict reduced AMPA receptor number at glutamatergic synapses on interneurons in mice lacking Dlx1, an interesting possibility that remains to be explored in future studies.

Intrinsic properties of interneurons lacking Dlx1.

Surviving interneurons in adult Dlx1−/− mice could have intrinsic membrane properties that could also lead them to release less GABA onto pyramidal neurons. For instance, these interneurons could have a more hyperpolarized resting membrane potential or lower threshold for spike generation, meaning that a given excitatory input would be less likely to lead to an action potential, and thus GABA release, from the interneuron. However, current-clamp recordings from interneurons in Dlx1 knockout mice older than P30 demonstrated that intrinsic firing properties are comparable to those of WT interneurons, arguing against this possibility. In P9–12 Dlx1−/− mice, however, CA1 interneurons exhibited a depolarized resting membrane potential and higher input resistance compared with WT interneurons, suggesting that interneurons lacking Dlx1 may undergo delayed maturation (Okaty et al. 2009).

How loss of Dlx1 might affect intrinsic membrane properties of young interneurons, and ion channel expression in particular, is unclear. Prenatally, Dlx1 (in conjunction with other Dlx genes) controls neurite extension of young neurons through regulation of cytoskeleton-associated factors (Cobos et al. 2007). In adult interneurons, Dlx1 promotes dendrite length and branch number development (Cobos et al. 2005). Cell size is one determinant of input resistance; if interneurons lacking Dlx1 are smaller at P9–12, this could contribute to the increased input resistance observed. However, measurements of capacitance in these neurons were not different between Dlx1−/− mice and WT littermates (data not shown), arguing against this possibility.

Interestingly, immature membrane properties of interneurons in young Dlx1 knockout mice might lead, in a homeostatic manner, to the reduction in interneuron excitation observed later in development. A depolarized resting membrane potential and increased input resistance at young ages could combine to enhance excitability of interneurons. Consistent with this prediction, our results show that interneurons lacking Dlx1, when recorded at P9–12, fire more frequently in response to current steps of a given size than do interneurons from WT littermates. In turn, this increased excitability could lead to the removal of AMPA receptors from glutamatergic synapses on these immature interneurons in Dlx1−/− mice as a compensatory response (Turrigiano et al. 1998) in an attempt to prevent excessive GABA release during the first few postnatal weeks, a time when GABA is depolarizing (Ben-Ari et al. 2007).

Conclusion and Perspective

Here we describe a functional reorganization of excitatory circuits in the hippocampus of mice lacking Dlx1. We also report a novel role for Dlx1 in the electrophysiological maturation of interneurons. Alterations in glutamatergic input to hippocampal interneurons are likely to be compensatory responses to reduced inhibition secondary to interneuron loss (Cobos et al. 2005) and delayed maturation of interneurons in young (P9–12) Dlx1−/− mice.

These findings confirm the hypothesis that loss of Dlx1 results in an imbalance between hippocampal excitation and inhibition that cannot be explained solely by the loss of a number of SOM, neuropeptide Y, and CR interneurons. These findings have implications not only for epilepsy, but also for neuropsychiatric disorders, in which alterations in interneuron function have been postulated to underlie circuit dysfunction (Rubenstein and Merzenich 2003; Lewis et al. 2005; Gogolla et al. 2009). For instance, reduced interneuron expression of GAD1 is a consistent phenotype in schizophrenia (Lewis et al. 2005; Lisman et al. 2008). It is hypothesized that reduced excitatory drive onto interneurons, through NMDA receptors, contributes to homeostatic reductions in GAD1 and GABA and thereby a reduction in inhibition (Lisman et al. 2008). Thus studies of studies of homeostatic regulation of circuit function may shed light on system deregulation in human neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders.

GRANTS

This work was supported by funds from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant R21-NS-066118–01A2 (to S. C. Baraban) and National Institute of Mental Health Grant F32-MH-087010-01A1 (to M. A. Howard).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. Sebe for helpful discussions and R. Estrada, E. Looke-Stewart, and S. Agerwala for genotyping and maintenance of the Dlx1 mouse colony.

REFERENCES

- Ben-Ari Y, Gaiarsa JL, Tyzio R, Khazipov R. GABA: a pioneer transmitter that excites immature neurons and generates primitive oscillations. Physiol Rev 87: 1215–1284, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Kayal AR, Shumate MD, Jin H, Rikhter TY, Coulter DA. Selective changes in single cell GABA(A) receptor subunit expression and function in temporal lobe epilepsy. Nat Med 4: 1166–1172, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt SJ, Fuccillo M, Nery S, Noctor S, Kriegstein A, Corbin JG, Fishell G. The temporal and spatial origins of cortical interneurons predict their physiological subtype. Neuron 48: 591–604, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calcagnotto ME, Paredes MF, Baraban SC. Heterotopic neurons with altered inhibitory synaptic function in an animal model of malformation-associated epilepsy. J Neurosci 22: 7596–7605, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobos I, Calcagnotto ME, Vilaythong AJ, Thwin MT, Noebels JL, Baraban SC, Rubenstein JL. Mice lacking Dlx1 show subtype-specific loss of interneurons, reduced inhibition, and epilepsy. Nat Neurosci 8: 1059–1068, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobos I, Long JE, Thwin MT, Rubenstein JL. Cellular patterns of transcription factor expression in developing cortical interneurons. Cereb Cortex 16 Suppl 1: i82–i88, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobos I, Borello U, Rubenstein JLR. Dlx transcription factors promote migration through repression of axon and dendrite growth. Neuron 54: 873–888, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cormier RJ, Kelly PT. Glutamate-induced long-term potentiation enhances spontaneous EPSC amplitude but not frequency. J Neurophysiol 75: 1909–1918, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter DA. Epilepsy-associated plasticity in gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor expression, function, and inhibitory synaptic properties. Int Rev Neurobiol 45: 237–252, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crino PB, Duhaime AC, Baltuch G, White R. Differential expression of glutamate and GABA-A receptor subunit mRNA in cortical dysplasia. Neurology 56: 906–913, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lanerolle NC, Kim JH, Robbins RJ, Spencer DD. Hippocampal interneuron loss and plasticity in human temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain Res 495: 387–95, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lanerolle NC, Kim JH, Williamson A, Spencer SS, Zaveri HP, Eid T, Spencer DD. A retrospective analysis of hippocampal pathology in human temporal lobe epilepsy: evidence for distinctive patient subcategories. Epilepsia 44: 677–687, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flames N, Marín O. Developmental mechanisms underlying the generation of cortical interneuron diversity. Neuron 46: 377–381, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogolla N, LeBlanc JJ, Quast KB, Südhof TC, Fagiolini M, Hensch TK. Common circuit defect of excitatory-inhibitory balance in mouse models of autism. J Neurodevelop Disord 1: 172–181, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DL, Baraban SC. Characterization of inhibitory circuits in the malformed hippocampus of Lis1 mutant mice. J Neurophysiol 98: 2737–2746, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DL, Baraban SC. Inhibitory inputs to hippocampal interneurons are reorganized in Lis1 mutant mice. J Neurophysiol 102: 648–658, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz B. The transmission of impulses from nerve to muscle, and the subcellular unit of synaptic action. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 155: 455–479, 1962 [Google Scholar]

- Lewis DA, Hashimoto T, Volk DW. Cortical inhibitory neurons and schizophrenia. Nat Rev Neurosci 6: 312–324, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisman JE, Coyle JT, Green RW, Javitt DC, Benes FM, Heckers S, Grace AA. Circuit-based framework for understanding neurotransmitter and risk gene interactions in schizophrenia. Trends Neurosci 31: 234–242, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loup F, Wieser HG, Yonekawa Y, Aguzzi A, Fritschy JM. Selective alterations in GABAA receptor subtypes in human temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci 20: 5401–5419, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manabe T, Renner P, Nicoll RA. Postsynaptic contribution to long-term potentiation revealed by the analysis of miniature synaptic currents. Nature 355: 50–55, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh E, Fulp C, Gomez E, Nasrallah I, Minarcik J, Sudi J, Christian SL, Mancini G, Labosky P, Dobyns W, Brooks-Kayal A, Golden JA. Targeted loss of Arx results in a developmental epilepsy mouse model and recapitulates the human phenotype in heterozygous females. Brain 132: 1563–1576, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okaty BW, Miller MN, Sugino K, Hempel CM, Nelson SB. Transcriptional and electrophysiological maturation of neocortical fast-spiking GABAergic interneurons. J Neurosci 29: 7040–7052, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell EM, Campbell DB, Stanwood GD, Davis C, Noebels JL, Levitt P. Genetic disruption of cortical interneuron development causes region- and GABA cell type-specific deficits, epilepsy, and behavioral dysfunction. J Neurosci 23: 622–631, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein JL, Merzenich MM. Model of autism: increased ratio of excitation/inhibition in key neural systems. Genes Brain Behav 2: 255–267, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotter SA, Kapur J, Anzivino MJ, Lee KS. GABAergic synaptic inhibition is reduced before seizure onset in a genetic model of cortical malformation. J Neurosci 26: 10756–10767, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrigiano GG, Leslie KR, Desai NS, Rutherford LC, Nelson SB. Activity-dependent scaling of quantal amplitude in neocortical neurons. Nature 391: 892–896, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang H, Chen HX, Yu XX, King MA, Roper SN. Reduced excitatory drive in interneurons in an animal model of cortical dysplasia. J Neurophysiol 96: 569–578, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu FH, Mantegazza M, Westenbroek RE, Robbins CA, Kalume F, Burton KA, Spain WJ, McKnight GS, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Reduced sodium current in GABAergic interneurons in a mouse model of severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy. Nat Neurosci 9: 1142–1149, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou FW, Roper SN. Altered firing rates and patters in interneurons in experimental cortical dysplasia. Cereb Cortex 2010. November 17 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu WJ, Roper SN. Reduced inhibition in an animal model of cortical dysplasia. J Neurosci 20: 8925–8931, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]