Abstract

Purpose

18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG PET) has been used to assess metabolic response several months after stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) for early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. However, whether a metabolic response can be observed already during treatment and thus can be used to predict treatment outcome is undetermined.

Methods

Ten medically inoperable patients with FDG PET-positive lung tumours were included. SBRT consisted of three fractions of 20 Gy delivered at the 80% isodose at days 1, 6 and 11. FDG PET was performed before, on day 6 immediately prior to administration of the second fraction of SBRT and 12 weeks after completion of SBRT. Tumour metabolism was assessed semi-quantitatively using the maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) and SUV70%.

Results

After the first fraction, median SUVmax increased from 6.7 to 8.1 (p = 0.07) and median SUV70% increased from 5.7 to 7.1 (p = 0.05). At 12 weeks, both median SUVmax and median SUV70% decreased by 63% to 3.1 (p = 0.008) and to 2.5 (p = 0.008), respectively.

Conclusion

SUV increased during treatment, possibly due to radiation-induced inflammation. Therefore, it is unlikely that 18F-FDG PET during SBRT will predict treatment success.

Keywords: SBRT, Lung tumours, Response monitoring, FDG PET

Introduction

Lobectomy is considered the treatment of choice for stage I lung tumours [1]. Until recently, conventionally fractionated radiotherapy was offered to medically inoperable patients. Unfortunately, retrospective data suggest poor overall survival rates for stage I disease treated with radiotherapy, even with the use of modern 3-D conformal radiotherapy [2]. Stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) is a relatively new approach in the treatment of lung tumours, utilizing stereotactic targeting and precise radiation delivery. SBRT facilitates hypofractionation with markedly increased biological equivalent doses (>100 Gy) and reduced overall treatment times. Numerous trials have now been published using SBRT for stage I lung tumours. Results are excellent, with local control rates above 80% at 1–5 years [3], comparable to those obtained with surgery. As a consequence, SBRT is gradually replacing conventionally fractionated radiotherapy for non-surgical patients.

18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG PET) imaging, visualizing enhanced glucose utilization by tumours, has proven to be useful as a predictive and prognostic test in various treatment settings including response assessment during (chemo-) radiotherapy. Also after SBRT, a metabolic response is observed weeks to months after treatment [4–6]. Being able to predict the outcome after SBRT in terms of complete tumour response already during treatment would yield two significant advantages: (1) the indication for SBRT could safely be extended to include operable patients, because the few patients who will fail after SBRT could be offered immediate salvage surgery and (2) follow-up after SBRT for all patients could be tailored according to the risk of failure. Both options are very appealing in order to increase the efficiency of early lung cancer treatment as well as follow-up.

We performed this pilot study to explore the potential of FDG PET with regard to early assessment of tumour response during SBRT in patients with FDG PET-positive lung tumours.

Materials and methods

Study design

Medically inoperable patients with an FDG PET-positive lesion in the lung without FDG uptake elsewhere were eligible (stage I lung cancer, according to the UICC TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours, 7th edition, 2009). Diagnostic work-up included bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage and biopsy, CT scan and lung function testing. Due to the small sizes and peripheral location of the target lesions, cytological and histological confirmation could not be obtained in any of the patients. Only one patient was regarded as having sufficient pulmonary reserve to undergo transthoracic biopsy, which resulted in pneumothorax without histological confirmation of the diagnosis. Patients had to have a WHO performance score of 0–2 and a life expectancy of at least 6 months. SBRT was delivered using a Novalis® system (BrainLAB AG, Feldkirchen, Germany), according to the protocol of the Department of Radiation Oncology at the University Medical Center Groningen. Briefly, after acquisition of a planning 4-D CT scan incorporating breathing motions, the target volume was delineated. Patients received 3 × 20 Gy at the 80% isodose level at days 1, 6 and 11, respectively. All patients underwent a routine 18F-FDG PET scan and CT scan 12 weeks after completion of SBRT for response evaluation. An additional 18F-FDG PET scan to assess early tumour response was performed at day 6, immediately before delivery of the second fraction. The study was approved by the local Medical Ethics Committee and all patients gave written informed consent prior to treatment.

Each 18F-FDG PET scan was made at the Department of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging on a Siemens/CTI ECAT EXACT HR+ machine, using the Dutch Standard Operating Procedures (SOP) for 18F-FDG PET whole-body scans [7]. In short, patients received FDG at a dose of 5 MBq per kilogram body weight intravenously. After a waiting period of 60 min, a scan was made from the mid-thigh to the external acoustic meatus.

Data analysis and statistics

Data were assessed visually and semi-quantitatively, using the maximum standardized uptake values (SUVmax) and the SUV70% (i.e. the mean SUV in the volume encompassing the isocontour of 70% of maximum activity). For SUV calculation, the tumour was delineated using standard Siemens e.soft analysis and viewing software in order to eliminate inter-observer variability. In order to render the SUVs on the three time points comparable, the waiting time between injection and scanning differed no more than 5 min among the three examinations, as defined in the SOP [7]. SUVs were corrected for the blood glucose levels (normalization to 5.0 mmol/l). SUVs are expressed as medians with range. Comparisons between the 18F-FDG PET scans at different time points were performed using the Wilcoxon signed rank test. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare groups of different metabolic responders. Additionally, metabolic response was assessed according to European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) criteria [8] (see Table 1). Routine CT thorax 12 weeks after completion of SBRT was used to assess tumour response according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) criteria version 1.1 [9].

Table 1.

Definition of metabolic response according to EORTC criteria

| Response | Definition |

|---|---|

| CMR | Complete resolution of FDG uptake in tumour, not distinguishable from surrounding tissue |

| PMR | Reduction of more than 25% in SUV |

| SMD | Changes of less than 25% in SUV |

| PMD | Increase of SUV of more than 25% or new (metastatic) lesions |

CMR complete metabolic response, PMR partial metabolic response, SMD stable metabolic disease, PMD progressive metabolic disease

Results

Patient characteristics

Ten patients were enrolled between February 2008 and January 2009 as planned. There were nine men and one woman with a median age of 77.5 years and a median Charlson comorbidity index of 4 (range 3–11). Tumour stage according to the 7th edition of the UICC TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours was T1a (n = 6), T1b (n = 3) and T2a (n = 1). The staging 18F-FDG PET scan was made 5.3 weeks (median; range 3–14 weeks) prior to the start of SBRT. All patients underwent an 18F-FDG PET scan on day 6. Routine 18F-FDG PET and CT scans were performed 12.9 weeks (median; range 11.7–18 weeks) after completion of SBRT for response evaluation. One patient refused the 18F-FDG PET at 12 weeks due to increasing claustrophobia, yielding nine fully evaluable patients. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics

| Patient | Sex | Age | Charlson index | cTNM | GTV (cm3) | SUVmax (before) | SUVmax (during) | SUVmax (12 weeks) | Metabolic response (12 weeks) | Radiological response (12 weeks) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 78 | 11 | T1a N0 M0 | 5.27 | 7.1 | 7.8 | 3.1 | PMR | PR |

| 2 | F | 88 | 4 | T1b N0 M0 | 7.10 | 16.4 | 13.1 | 1.4 | CMR | PR |

| 3 | M | 71 | 4 | T1a N0 M0 | 4.16 | 4.1 | 5.3 | 1.7 | CMR | PR |

| 4 | M | 61 | 3 | T1a N0 M0 | 2.74 | 6.3 | 8.3 | 1.7 | CMR | PR |

| 5 | M | 81 | 4 | T1a N0 M0 | 5.87 | 9.0 | 14.5 | NA | NA | PR |

| 6 | M | 77 | 5 | T2a N0 M0 | 16.71 | 24.8 | 32.2 | 3.5 | PMR | PR |

| 7 | M | 81 | 3 | T1b N0 M0 | 1.32 | 14.6 | 15.5 | 3.5 | PMR | SD |

| 8 | M | 64 | 4 | T1a N0 M0 | 0.90 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 1.6 | CMR | PR |

| 9 | M | 85 | 5 | T1b N0 M0 | 9.55 | 4.3 | 5.2 | 3.2 | PMR | SD |

| 10 | M | 61 | 4 | T1a N0 M0 | 2.89 | 5.0 | 5.4 | 3.2 | PMR | PR |

GTV gross tumour volume, CMR complete metabolic response, PMR partial metabolic response, SMD stable metabolic disease, PMD progressive metabolic disease, PR partial response, SD stable disease

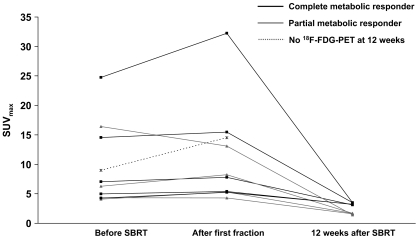

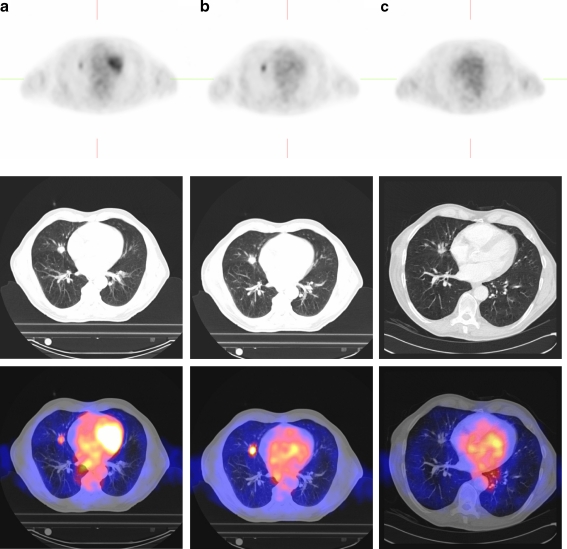

Metabolic and radiological response

Prior to SBRT, median SUVmax was 6.7 (range 4.1–24.8) and median SUV70% was 5.7 (range 3.4–20.0). After the first fraction, median SUVmax increased to 8.1 (p = 0.07) (Fig. 1) and median SUV70% increased to 7.1 (p = 0.05), representing a relative increase of 18 and 21%, respectively. At 12 weeks, a metabolic response was observed in all evaluable patients (n = 9). Four patients showed a complete metabolic response (CMR) (44%) and five patients showed a partial metabolic response (56%). Both SUVmax and SUV70% decreased significantly by 63% (p = 0.008) to 3.1 and 2.5, respectively. CMR was not associated with gross tumour volume (GTV) (p = 0.29) or SUVmax prior to treatment (p = 0.34). Routine CT thorax performed 12 weeks after SBRT showed a partial response in eight patients (80%) and stable disease in two patients (20%). Sequential PET/CT images of patient 3 are presented in Fig. 2.

Fig. 1.

Absolute SUVmax before, after the first fraction and 12 weeks after completion of SBRT. SUVmax increased after the first fraction (p = 0.07) and decreased significantly 12 weeks after SBRT (p = 0.008)

Fig. 2.

Sequential axial PET (upper row), CT (middle row) and fused PET/CT (lower row) images of patient 3, before (a), after the first fraction (b) and 12 weeks after SBRT (c). SUVmax increased from 6.3 to 8.3 after the first fraction. At 12 weeks SUVmax decreased to 1.3 (CMR) and was considered a partial response according to RECIST criteria

Discussion

SBRT has demonstrated excellent local control rates in medically inoperable patients, establishing an important role for definitive SBRT in the treatment of stage I lung tumours. Since local control rates after SBRT are comparable to those obtained with surgery, it could be argued that primary SBRT might also be offered to operable patients as an alternative to lobectomy. This hypothesis is the basis for the phase II RTOG 0618 trial and two randomized phase III trials, i.e. the Dutch ROSEL trial [10] and the STARS trial [11], both comparing SBRT with surgery. As operable patients receiving SBRT would remain eligible for potential salvage surgery in the case of tumour failure, early prediction of local control already during treatment is tempting since salvage surgery could then be performed without the need to complete SBRT and subsequent 3-monthly follow-up response monitoring.

In our study, the 18F-FDG PET scan preceding the second of three fractions of SBRT showed an increased 18F-FDG uptake in the tumour. A number of explanations may exist for this phenomenon. First, the interval between the staging 18F-FDG PET scan and the start of SBRT varied widely. Tumour progression may have occurred in between and may be responsible for the increased uptake. However, no correlation between SUV changes after the first fraction and the interval between the staging FDG PET and start of SBRT was found, suggesting that tumour progression did not play a major role (data not shown). Another explanation may be that 18F-FDG PET also detects inflammation [12]; thus, the elevated FDG uptake may be explained by radiation-induced inflammation with influx of macrophages, which are known to exhibit increased 18F-FDG uptake [13]. Indeed, increased 18F-FDG uptake has been observed during radiotherapy in patients [6, 14, 15] as well as in a preclinical study [16]. Dynamic scanning with kinetic analysis [17] or dual time point imaging [18, 19] may have been more accurate for the discrimination between tumour activity and radiation-induced inflammation. Also, the use of other tracers capable of discriminating inflammation from tumour activity, such as proliferation markers, may be promising and needs further investigation. Finally, despite inclusion in the Dutch recommendations, the practice of correcting for plasma glucose is controversial and certainly not widely used [7]. If we would have used the uncorrected data, the increase observed after the first fraction would have been 6% for SUVmax and 9% for SUV70%. The reduced SUVs at 12 weeks would remain unchanged, i.e. 63%.

In our institution, follow-up of lung cancer patients treated with SBRT consists of an 18F-FDG PET/CT scan at 12 weeks, followed by yearly CT scans of the thorax. It must be kept in mind that the response assessment at 12 weeks is not the standard of care. Its results should be interpreted with caution, especially since a substantial proportion of patients may have persistently elevated SUV up to 1 year after treatment without developing local recurrence [6]. Secondly, 12 weeks is too early to elicit a radiological response and longer intervals are needed to observe tumour shrinkage or disappearance.

In conclusion, given the expectation of at least 80% local control after SBRT, it is unlikely that 18F-FDG PET during SBRT will predict treatment success. Advanced scanning techniques or the use of innovative PET tracers are needed for early response assessment during hypofractionated high-dose radiotherapy techniques such as SBRT.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

None.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Reif MS, Socinski MA, Rivera MP. Evidence-based medicine in the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Chest Med. 2000;21(1):107–120. doi: 10.1016/S0272-5231(05)70011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lagerwaard FJ, Senan S, van Meerbeeck JP, Graveland WJ, Rotterdam Oncological Thoracic Study Group Has 3-D conformal radiotherapy (3D CRT) improved the local tumour control for stage I non-small cell lung cancer? Radiother Oncol. 2002;63(2):151–157. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8140(02)00009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chi A, Liao Z, Nguyen NP, Xu J, Stea B, Komaki R. Systemic review of the patterns of failure following stereotactic body radiation therapy in early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer: clinical implications. Radiother Oncol. 2010;94(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ishimori T, Saga T, Nagata Y, Nakamoto Y, Higashi T, Mamede M, et al. 18F-FDG and 11C-methionine PET for evaluation of treatment response of lung cancer after stereotactic radiotherapy. Ann Nucl Med. 2004;18(8):669–674. doi: 10.1007/BF02985960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoopes DJ, Tann M, Fletcher JW, Forquer JA, Lin PF, Lo SS, et al. FDG-PET and stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) for stage I non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2007;56(2):229–234. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henderson MA, Hoopes DJ, Fletcher JW, Lin PF, Tann M, Yiannoutsos CT, et al. A pilot trial of serial 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in patients with medically inoperable stage I non-small-cell lung cancer treated with hypofractionated stereotactic body radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76(3):789–795. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.02.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boellaard R, Oyen WJ, Hoekstra CJ, Hoekstra OS, Visser EP, Willemsen AT, et al. The Netherlands protocol for standardisation and quantification of FDG whole body PET studies in multi-centre trials. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35(12):2320–2333. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-0874-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young H, Baum R, Cremerius U, Herholz K, Hoekstra O, Lammertsma AA, et al. Measurement of clinical and subclinical tumour response using [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose and positron emission tomography: review and 1999 EORTC recommendations. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) PET Study Group. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35(13):1773–1782. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(99)00229-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hurkmans CW, Cuijpers JP, Lagerwaard FJ, Widder J, van der Heide UA, Schuring D, et al. Recommendations for implementing stereotactic radiotherapy in peripheral stage IA non-small cell lung cancer: report from the Quality Assurance Working Party of the randomised phase III ROSEL study. Radiat Oncol. 2009;4:1. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00840749

- 12.Sugawara Y, Braun DK, Kison PV, Russo JE, Zasadny KR, Wahl RL. Rapid detection of human infections with fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose and positron emission tomography: preliminary results. Eur J Nucl Med. 1998;25(9):1238–1243. doi: 10.1007/s002590050290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kubota R, Yamada S, Kubota K, Ishiwata K, Tamahashi N, Ido T. Intratumoral distribution of fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose in vivo: high accumulation in macrophages and granulation tissues studied by microautoradiography. J Nucl Med. 1992;33(11):1972–1980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Baardwijk A, Bosmans G, Dekker A, van Kroonenburgh M, Boersma L, Wanders S, et al. Time trends in the maximal uptake of FDG on PET scan during thoracic radiotherapy. A prospective study in locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients. Radiother Oncol. 2007;82(2):145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hautzel H, Müller-Gärtner HW. Early changes in fluorine-18-FDG uptake during radiotherapy. J Nucl Med. 1997;38(9):1384–1386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murayama M, Harada N, Kakiuchi T, Fukumoto D, Kamijo A, Kawaguchi AT, et al. Evaluation of D-18F-FMT, 18F-FDG, L-11C-MET, and 18F-FLT for monitoring the response of tumors to radiotherapy in mice. J Nucl Med. 2009;50(2):290–295. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.057091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta N, Gill H, Graeber G, Bishop H, Hurst J, Stephens T. Dynamic positron emission tomography with F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose imaging in differentiation of benign from malignant lung/mediastinal lesions. Chest. 1998;114(4):1105–1111. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.4.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suga K, Kawakami Y, Hiyama A, Sugi K, Okabe K, Matsumoto T, et al. Dual-time point 18F-FDG PET/CT scan for differentiation between 18F-FDG-avid non-small cell lung cancer and benign lesions. Ann Nucl Med. 2009;23(5):427–435. doi: 10.1007/s12149-009-0260-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanz-Viedma S, Torigian DA, Parsons M, Basu S, Alavi A. Potential clinical utility of dual time point FDG-PET for distinguishing benign from malignant lesions: implications for oncological imaging. Rev Esp Med Nucl. 2009;28(3):159–166. doi: 10.1016/S0212-6982(09)71360-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]