Abstract

Aims

Transcatheter treatment of heart valve disease is well established today. However, for the treatment of tricuspid regurgitation (TR), no effective catheter-based approach is available. Herein, we report the first human case description of transcatheter treatment of severe TR in a 79-year-old patient with venous congestion and associated non-cardiac diseases. In this patient, surgical treatment had been declined and pharmacological therapy had been ineffective. After ex vivo and animal studies, the treatment of TR was performed by percutaneous caval valve implantation.

Methods and results

In a transcatheter approach through the right femoral vein, a custom-made self-expanding heart valve was implanted into the inferior vena cava (IVC). The device was anchored in the IVC at the cavoatrial junction with the level of the valve aligned immediately above the hepatic inflow and protruding into the right atrium. After deployment, excellent valve function was observed resulting in a marked reduction in caval pressure and an abolition of the ventricular wave in the IVC. Sequential echocardiographic exams over a follow-up period of 8 weeks confirmed continuous device function without paravalvular leakage or remaining venous regurgitation. The patient experienced improved physical capacity and was able to resume off-bed activities. There was no recurrence of right heart failure during follow-up and a partial reduction of ascites. The patient was discharged from hospital into a rehabilitation programme.

Conclusion

Transcatheter treatment of severe TR by caval valve implantation is feasible resulting in an immediate abolition of IVC regurgitation and mid-term clinical improvement. Thus, in selected non-surgical patients, caval valve implantation may become a therapeutic option to treat venous regurgitation and improve associated non-cardiac diseases. Further confirmatory experience with longer follow-up is required to evaluate the long-term clinical benefit of the procedure as well as potential deleterious effects.

Keywords: Tricuspid regurgitation, Transcatheter tricuspid valve implantation, Valvular heart disease

Introduction

Since the first human percutaneous valve replacement by Bonhoeffer et al.1 10 years ago, interventional treatment of heart valve disease has rapidly advanced. Today, transcatheter therapy has gained increasing acceptance as a treatment option for patients with aortic-, mitral- and pulmonic valve disease, who are at high risk for conventional surgery.2–4 Despite these advances, no catheter-based approach is yet available for the treatment of tricuspid regurgitation (TR) and only limited experimental data have been published so far.5–7 Surgical tricuspid valve (TV) repair is the only available treatment option and most repairs are performed in the context of other planned cardiac surgery. As severe TR is often associated with late-stage myocardial or left heart valve disease, reoperations for recurrent TR are particularly high-risk procedures.8–10 A readily available transcatheter approach could offer a treatment alternative, particularly for patients currently considered inoperable.

From the interventional perspective, there are two principle concepts regarding the possible site of percutaneous valve implantation—orthotopic vs. heterotopic TV replacement. For orthotopic valve replacement, the prosthetic valve is positioned in the TV annulus which, however, offers little resistance for long-term valve fixation due to its anatomic structure and flexible nature. Thus, orthotopic TV replacement would require innovative solutions for stent and valve fixation and has not yet been reported in human patients. Heterotopic TV implantation is an alternative approach involving valve implantation in the central venous position at the cavoatrial junction. This novel concept recently suggested by our group has been extensively investigated in pre-clinical studies which demonstrated the haemodynamic effect of caval valves in animals for up to 6 months of follow-up.11 Thus, heterotopic valve implantation offers a potential therapeutic option for inoperable patients suffering from severe TR with venous congestion. Herein, we report the first-in-man application of this treatment concept for severe TR involving inferior caval valve implantation.

Methods

Patient

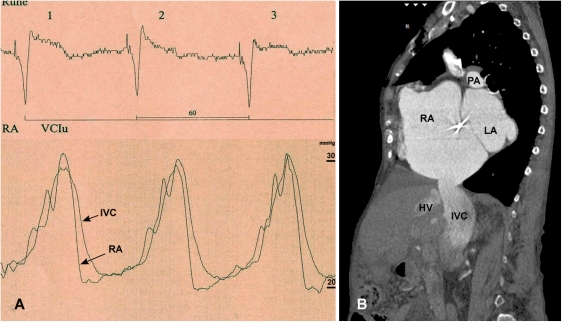

The procedure was performed as ‘compassionate treatment' in a 79-year-old female patient with severe functional TR. Upon evaluation by a multidisciplinary team (cardiologist, cardiac surgeon), the patient was considered inoperable due to multiple previous open-heart surgeries, significant co-morbidities (including chronic kidney dysfunction, logistic EuroScore 29.7%), as well as for technical reasons. Her medical history included open surgical valvuloplasty for rheumatic mitral valve stenosis in 1966, mitral valve replacement with a mechanical tilt-disc prosthesis in 1986, and TV repair by a partial purse-string suture technique (‘DeVega-technique') in 2000. Transthoracic echocardiography had revealed recurrent functional TR grade IV with right ventricular (RV) enlargement and mildly reduced RV function [tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) 16 mm; tricuspid annular systolic velocity (TASV) 6.3 cm/s). Left ventricular function was preserved (ejection fraction 65%). Right heart catheterization and angiography confirmed severe TR with massive venous regurgitation. The mean pulmonary artery pressure was lightly elevated at 29 mmHg with a normal pulmonary vascular resistance at 123 dyn s/cm5. Haemodynamic evaluation confirmed a prominent ventricular wave of 30 mmHg in the right atrium (RA) and in the inferior vena cava (IVC) which was transmitted down to the femoral veins (Figure 1A). A computed tomographic (CT) angiogram performed for diagnostic purpose visualized massive venous backflow of contrast from the RA into the IVC down to the renal veins (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Severe tricuspid regurgitation with inferior vena cava congestion before device implantation. (A) Right heart catheterization confirms a prominent ventricular wave of 30 mmHg in the right atrium and the inferior vena cava which is transmitted down to the femoral veins. (B) A computed tomographic angiogram with contrast injected into the superior vena cava visualized massive backflow into the IVC down to the level of the renal veins. RA, right atrium; IVC, inferior vena cava; HV, hepatic vein; LA, left atrium; PA, pulmonary artery.

Throughout the past years, the patient had suffered from progressive symptoms of RV congestion with peripheral oedema, cirrhose cardiaque, and persistent ascites with gastrointestinal dysfunction. Recent deterioration of symptoms refractory to pharmacological treatment made it impossible to resume off-bed activities. Under these circumstances, institutional review board approval was obtained and the patient consented to attempt transcatheter caval valve implantation.

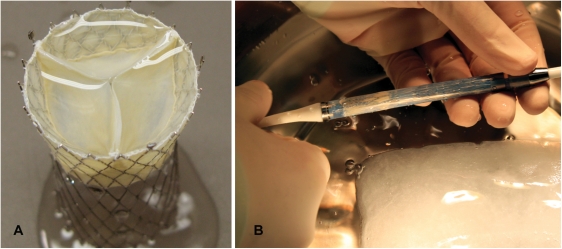

Device

A self-expanding percutaneous heart valve was designed for implantation into the IVC to protect the abdominal vasculature from elevated venous pressure and systolic backflow in severe TR. To avoid occlusion of hepatic vein inflow just below the diaphragm, the device was designed with the upper valve segment protruding into the RA and the lower segment for anchoring in the IVC. Prior to manufacturing the device, a CT angiogram was obtained to assess the anatomy and diameter of the uppermost IVC segment and the cavoatrial junction. A self-expanding tubular stent was then tailored to the dimension of the anticipated landing zone in the IVC and manufactured of nitinol by laser-cutting. The stent frame was shaped like an hourglass with a total length of 70 mm, a maximum diameter of 43 mm, and the middle segment constrained to facilitate fixation at the cavoatrial junction. The proximal stent segment was then mounted with a tri-leaflet porcine pericardial valve and a sleeve covering the inside down to the base of the leaflets to prevent paravalvular leakage (Figure 2A). Valve function and anchoring force were tested using a prototype device in an ex vivo pulse duplicator model which demonstrated satisfactory short-term function under simulated venous low-flow conditions. The device was stored in 0.2% glutaraldehyde until use.

Figure 2.

Self-expanding percutaneous heart valve for inferior vena cava implantation. (A) The device was designed with the upper valve segment protruding into the right atrium and the lower segment for anchoring in the inferior vena cava. The middle segment constrained to facilitate fixation at the cavoatrial junction. The proximal stent segment is mounted with a tri-leaflet porcine pericardial valve and a sleeve covering the inside down to the base of the leaflets. (B) The valve was loaded into a 27 F catheter for implantation.

Procedure

The implantation procedure was performed under general anaesthesia and mechanical ventilation in a hybrid operating room. A 5 F arterial catheter was placed in the left femoral artery and used for continuous blood pressure monitoring. Two 7 F sheaths were placed in the right internal jugular vein and the left femoral vein for pressure measurement. Prior to valve implantation, confirmatory right heart catheterization was performed. An angiogram of the IVC and the RA was obtained confirming severe TR with regurgitation of contrast into the caval and hepatic veins. Two 7 F pigtail catheters were then positioned in the RA and IVC for continuous pressure monitoring.

Prior to implantation, the prosthetic valve was rinsed in saline, carefully crimped in iced water, and loaded into a custom-made 27 F implantation catheter (Figure 2B). After puncture of the right femoral vein, a straight 0.035 in. guidewire was placed in the vein. After a small skin incision, the catheter was easily advanced in the Seldinger technique through the femoral vein and the IVC into the RA. After confirming the catheter position under fluoroscopic and echocardiographic visualization, the uppermost 20 mm of the valve was partially unloaded. The constrained segment of the stent frame was then aligned with the cavoatrial junction by careful pullback of the catheter. With a safety margin of ∼5 mm, care was taken to avoid a low or high valve position causing either hepatic vein obstruction or paravalvular regurgitation. After a satisfactory position was confirmed, the device was released from the catheter.

Transoesophageal echocardiography was performed immediately after the procedure and repeated every 2 weeks after implantation. Transthoracic echocardiography and abdominal sonography were obtained 24 h and 7 days after the implantation. A CT angiogram was performed after 8 weeks of follow-up.

Results

Haemodynamic measurements

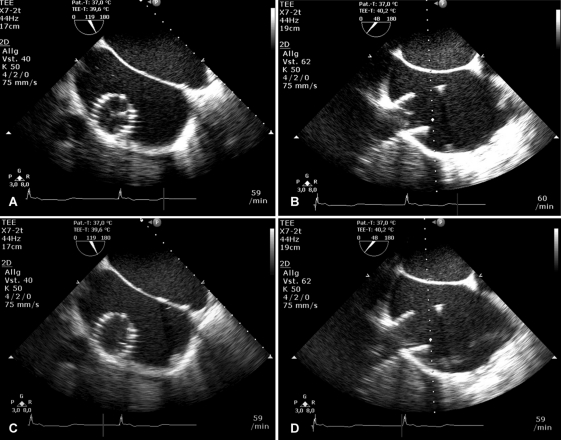

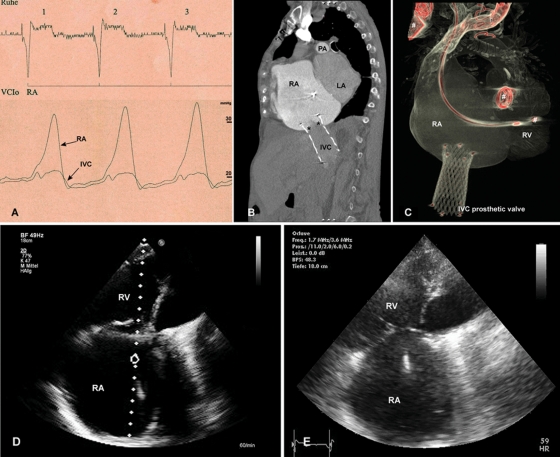

Immediately after deployment, excellent function of the device was observed. Transoesophageal echo confirmed valvular competence with full systolic closure and diastolic opening of the leaflets without any sign of paravalvular regurgitation (Figure 3). Haemodynamic measurements confirmed a nearly abolished ventricular wave in the IVC from 29/19 to 19/12 mmHg and mean IVC pressure decreased from 19 to 16 mmHg (Figure 4A). Right atrial pressure increased from 28/10 to 38/13 mmHg after valve implantation (Table 1). The patient remained haemodynamically stable at all times during the implantation and was extubated within 30 min after the procedure. After an uneventful early post-operative course, she was transferred from the intensive care unit to the ward on the following day.

Figure 3.

Echocardiographic evaluation of prosthetic valve function systolic closure (A and B) and diastolic opening (C and D) of the pericardial valve is visualized by transoesophageal echocardiography after the implantation procedure. Short- and long-axis views of the device after deployment. Doppler interrogation confirmed valvular competence and a continuously antegrade blood flow in the inferior vena cava and the hepatic veins without flow reversal.

Figure 4.

After device implantation, (A) deployment of the self-expanding valve resulted in the immediate abolition of regurgitation into the inferior vena cava. Simultaneous pressure measurement in the right atrium and the inferior vena cava confirms a reduction in the v-wave. (B) A computed tomographic angiogram 8 weeks after implantation with contrast injected in superior vena cava visualizes valve function without backflow into the inferior vena cava. The level of the leaflets (asterisks) is aligned with the cavoatrial junction, thus protecting of the hepatic vein from elevated right atrium pressure. (C) Three-dimensional reconstruction confirms the forward-tilted position of the valve in the inferior vena cava. (D) Transthoracic echo after 8 weeks visualizes right atrial and right ventricular enlargement; however, right heart morphology and function remained unchanged compared with the (E) pre-operative state. RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle; IVC, inferior vena cava; LA, left atrium; PA, pulmonary artery. Previously implanted devices (pacer leads, prosthetic mitral valve) are marked with #.

Table 1.

Haemodynamic parameters and right ventricular function before and after inferior vena cava valve implantation

| Before implantation | After implantation | |

|---|---|---|

| Heart rate (b.p.m.) | 60 | 60 |

| Right atrial pressure (mmHg) | 28/10 | 38/13 |

| Inferior vena cava pressure (mmHg) | 29/19 | 19/12 |

| TV annulus (mm) | 46 | 46a |

| TAPSE (mm) | 16 | 15a |

| TASV (cm/s) | 6.3 | 6.8a |

TV, tricuspid valve; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion; TASV, tricuspid annular systolic velocity.

aDetermined 8 weeks after implantation.

Assessment of valve function during follow-up

Valve function remained excellent during the first 8 weeks of follow-up. Doppler interrogation of the valve confirmed valvular competence and a continuously antegrade blood flow in the IVC and the hepatic veins without flow reversal. By planimetry, the prosthetic valve area was 2.9 cm2 with a mean transvalvular gradient <1 mmHg. After 8 weeks, a CT angiogram demonstrated valvular competence without regurgitation of contrast into the IVC (Figure 4B). An unchanged forward-tilting position of the prosthetic valve was confirmed in a supine position related to the anatomic course of the IVC (Figure 4C).

Clinical evolution

After device implantation, diuretic therapy was left unchanged. Within the first 8 weeks after implantation, the patient experienced a gradual improvement of symptoms related to venous congestion and right heart failure. Femoral venous pulsation was no longer detectable after implantation and the patient was able to resume off-bed activities and walk on the ward without assistance after 4 days. Early after the procedure, the patient suffered from temporary neck pain and recurring epistaxis, which subsided when anticoagulation with heparin was discontinued and replaced by coumarin. The post-operative course was delayed by non-cardiac complications, including an infection of the femoral puncture site with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Three weeks after implantation, the patient was discharged to a cardiac rehabilitation programme. During follow-up visits, she reported improved physical capacity from NYHA functional class IV to III. Peripheral oedema did not recur and ascites resolved partially, however remained detectable secondary to hepatic cirrhosis.

Discussion

This first report of transcatheter treatment of severe TR in a human patient demonstrates the feasibility of self-expanding valve implantation into the IVC with leading to a prompt haemodynamic and short-term clinical improvement. After deployment, excellent valve function was documented with an immediate abolition of IVC regurgitation (Figures 3 and 4). Paravalvular leakage and systolic flow reversal in the IVC and the hepatic veins were ruled out by angiography at the time of implantation and by Doppler interrogation during follow-up. Valve function remained unchanged during sequential assessment. During early follow-up, the patient experienced a reduction in clinical symptoms associated with venous congestion and an improvement of physical capacity from NYHA IV to NYHA III functional class.

In contrast to our previous experience in animals reporting double-valve implantation into the IVC and superior vena cava (SVC), in this first human case, we implanted a single valve into the IVC only.11 This rather simple procedure was performed because the patient primarily suffered from symptoms associated with IVC congestion, as well as for several technical reasons. From pre-clinical experience, we were aware of the fact that in severe TR, anchoring a self-expanding valve at the upper cavoatrial junction can be associated with complications due to the distention of the SVC. In our patient, imaging studies had revealed a severe enlargement of the RA resulting in a ‘funnel-shape' of the SVC cavoatrial junction, a condition involving a high risk of valve migration into the RA following deployment of the current device. Moreover, the presence of a pacemaker lead would have potentially complicated sufficient anchoring of the SVC device.

In patients with severe TR and multiple co-morbidities, TV surgery is frequently rejected because of a prohibitive operative risk. Reoperations for recurrent TR are particularly high-risk procedures with an in-hospital mortality of up to 37%. In addition, pharmacological therapy is often ineffective in achieving sustained improvement of symptoms.10 In our patient, surgical TV repair or replacement was no option both for technical reasons and due to significant co-morbidities. In contrast, percutaneous valve implantation into the IVC was easily performed in a straightforward approach without difficulties. Haemodynamic improvement was achieved by a reduction in IVC regurgitation as well as the improvement of symptoms of IVC congestion in this particular case. Nevertheless, the long-term clinical benefit in patients with TR in end-stage heart disease has not yet been investigated, and thus, there is a need for confirmation by further clinical experience and a longer follow-up period.

When considering this treatment concept for TR in human patients, several technical as well as physiological limitations have to be acknowledged. Severe TR is associated with structural changes of the RA and the caval veins. In these patients, the anatomic diameter of the IVC may show a substantial variation (reaching a diameter of up to 45 mm in isolated cases), thus requiring a specific, potentially individual solution for the device design and implantation procedure. In contrast to other stent valves available for transcatheter aortic valve implantation, the larger diameter of the IVC valve poses additional difficulties for tissue valve engineering. Along with the diameter, the biological valve profile has to be increased to avoid leaflet prolapse (e.g. a 45 mm tissue valve would require a height of >28 mm corresponding to a height-to-diameter ratio of 62%).

Secondly, the haemodynamic proof of IVC regurgitation is required prior to heterotopic valve implantation. In particular, in chronic TR with RA and RV enlargement, the RA functions as a reservoir by reducing the prominence of the ventricular wave and limiting the backflow of blood to the IVC. As pulsatile blood flow and systolic flow reversal in the IVC are prerequisites for proper valve function, the IVC valve is likely to have a haemodynamic effect only in patients with severe TR and preserved RV function.12 The significance of preserved RV function is already known to affect outcome after TV surgery and, to a certain degree, should also be taken into account in interventional TV replacement. The procedure results in ventricularization of the RA with persistence of RV and atrial volume overload. Right ventricular preload may actually increase with a subsequent rise in cardiac output as observed in pre-clinical studies. However, although not observed in this case, the increase in RV preload may promote further morphological changes of the RA and RV with potential deleterious effects on cardiac function and rhythm during long-term follow-up. In patients with severely reduced RV function or severely elevated pulmonary artery pressure, an increase in preload after device implantation may promote RV failure. Thus, these patients are rather unlikely to profit from the procedure.

Thirdly, IVC valve implantation only addresses the regurgitation of blood into the IVC. After valve deployment, the hepatic veins have to be protected from elevated atrial pressure, but must not be obstructed by the device. In this context, our concept of designing a valve protruding into the RA and anchored in the IVC with a long stent has proven to be successful. As observed in pre-clinical animal studies, the caval valves demonstrated a strong fixation to the venous wall after 4 weeks due to fibrous covering, thus making device migration beyond this time point highly unlikely. Furthermore, valve implantation in the low-flow and low-pressure venous circulation requires lifelong oral anticoagulation to prevent device thrombosis.

In summary, we herein present the first human case of IVC valve implantation in a non-surgical patient suffering from severe TR and refractory symptoms of venous congestion resulting in haemodynamic improvement and early symptomatic relief. This interventional concept is targeted for a severely ill group of patients with significant TR not amenable to surgical valve repair or replacement in end-stage heart disease. Further studies are required to evaluate the clinical benefit of the procedure during long-term follow-up. Additional indications may arise depending on clinical experience and long-term animal studies. Although the treatment offers a high likelihood for clinical improvement in this severely ill subgroup of patients, the costs involved for this type of procedure should be taken into account and carefully weighed against the clinical benefit.

Funding

This development is funded by a research grant from the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (100% total funding, ID BMBF #01 EZ 0907). Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by Department of Internal Medicine I, University Heart Center Jena.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.Bonhoeffer P, Boudjemline Y, Saliba Z, Merckx J, Aggoun Y, Bonnet D, Acar P, Le Bidois J, Sidi D, Kachaner J. Percutaneous replacement of pulmonary valve in a right-ventricle to pulmonary-artery prosthetic conduit with valve dysfunction. Lancet. 2000;356:1403–1405. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02844-0. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02844-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zahn R, Gerckens U, Grube E, Linke A, Sievert H, Eggebrecht H, Hambrecht R, Sack S, Hauptmann KE, Richardt G, Figulla HR, Senges J on behalf of the German Transcatheter Aortic Valve terventions—Registry Investigators. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation: first results from a multi-centre real-world registry. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:198–204. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khambadkone S, Coats L, Taylor A, Boudjemline Y, Derrick G, Tsang V, Cooper J, Muthurangu V, Hegde SR, Razavi RS, Pellerin D, Deanfield J, Bonhoeffer P. Percutaneous pulmonary valve implantation in humans: results in 59 consecutive patients. Circulation. 2005;112:1189–1197. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.523266. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.523266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tamburino C, Ussia GP, Maisano F, Capodanno D, La Canna G, Scandura S, Colombo A, Giacomini A, Michev I, Mangiafico S, Cammalleri V, Barbanti M, Alfieri O. Percutaneous mitral valve repair with the MitraClip system: acute results from a real world setting. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1382–1389. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq051. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehq051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boudjemline Y, Agnoletti G, Bonnet D, Behr L, Borenstein N, Sidi D, Bonhoeffer P. Steps toward the percutaneous replacement of atrioventricular valves an experimental study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:360–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.01.063. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2005.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lauten A, Figulla HR, Willich C, Jung C, Rademacher W, Schubert H, Ferrari M. Heterotopic valve replacement as an interventional approach to tricuspid regurgitation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:499–500. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.09.034. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2009.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bai Y, Zong GJ, Wang HR, Jiang HB, Wang H, Wu H, Zhao XX, Qin YW. An integrated pericardial valved stent special for percutaneous tricuspid implantation: an animal feasibility study. J Surg Res. 2010;160:215–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.10.029. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2008.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rogers JH, Bolling SF. The tricuspid valve: current perspective and evolving management of tricuspid regurgitation. Circulation. 2009;119:2718–2725. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.842773. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.842773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh SK, Tang GH, Maganti MD, Armstrong S, Williams WG, David TE, Borger MA. Midterm outcomes of tricuspid valve repair versus replacement for organic tricuspid disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82:1735–1741. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.06.016. discussion 1741 doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernal JM, Morales D, Revuelta C, Llorca J, Gutierrez-Morlote J, Revuelta JM. Reoperations after tricuspid valve repair. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130:498–503. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.12.044. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lauten A, Figulla HR, Willich C, Laube A, Rademacher W, Schubert H, Bischoff S, Ferrari M. Percutaneous caval stent valve implantation: investigation of an interventional approach for treatment of tricuspid regurgitation. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1274–1281. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp474. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehp474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lauten A, Ferrari M, Figulla HR. Letter by Lauten et al. regarding article, Interventional cardiology perspective of functional tricuspid regurgitation. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3:e10. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.110.944926. author reply e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]