History and Physical Examination

A 45-year-old Liberian woman was referred by her primary care physician for left arm pain and drainage from a fistulous tract on the posterior aspect of the left deltoid muscle. The arm pain began 3 years prior, and the patient initially sought attention in her home country. Although medical records from Liberia were not available, she reported undergoing bone débridement twice in the first year of illness. The drainage ceased after the second débridement. The patient had lived in the capital city of Liberia until she immigrated to the United States 2 years after onset. Shortly thereafter, she again had a draining fistulous tract develop although she waited another year before presenting to the orthopaedic clinic.

Review of systems revealed a 1-month history of low-grade fevers and night sweats. She denied exposure to tuberculosis or contact with animals. Physical examination revealed an oblique, deltopectoral healed incision with a small punctuate area that drained purulent fluid. There was an additional small, healed incision on the posterior aspect of the left deltoid. She had 20° flexion and 20° abduction of the humerus. Laboratory values included a normal complete blood count, a negative HIV ELISA, and a negative tuberculin skin test. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 51 mmol/L and C-reactive protein (CRP) was 51 mg/L.

Imaging studies, including plain radiographs (Fig. 1) and MRI (Figs. 2, 3), were performed.

Fig. 1.

An AP radiograph of the left shoulder, Grashey view, shows postsurgical changes to the left proximal humerus without cortical destruction or erosion.

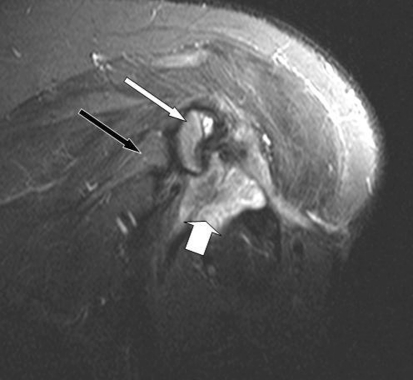

Fig. 2.

A coronal STIR image of the left shoulder shows a high signal fluid collection (thick white arrow) adjacent to the edematous residual humeral head (thin white arrow). The glenoid is normal (thin black arrow).

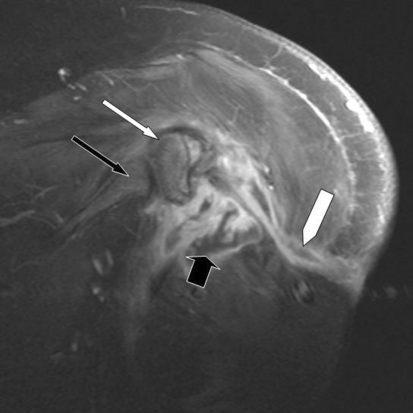

Fig. 3.

A coronal postcontrast T1-weighted MR image shows peripheral rim enhancement of the fluid collection (thick black arrow) and an enhancing fistulous tract leading to the skin surface (white block arrow). There is mild enhancement of the residual humeral head (thin white arrow) without appreciable enhancement of the glenoid (thin black arrow.)

Based on the history, physical examination, laboratory tests, and imaging studies, what is the differential diagnosis?

Imaging Interpretation

Plain film evaluation of the left shoulder (Fig. 1) revealed a postsurgical appearance to the proximal left humerus with a 4- to 5-cm resection of the proximal humeral metaphysis. The majority of the epiphysis was spared. The resection margins were well corticated without evidence of erosion or destruction. The residual humeral head was irregular with areas of mixed lucency and sclerosis suggesting chronicity, but the articulating surface was largely intact. The adjacent glenoid was normal. There was slight inferior subluxation of the glenohumeral joint, likely secondary to altered mechanics from the postsurgical changes.

An MRI was performed with and without contrast enhancement. A coronal STIR image (Fig. 2) revealed an area of heterogeneously hyperintense signal at the resection site, thought to be a combination of fluid and edematous tissue. Additional findings included marrow edema in the residual portion of the humeral head and a high signal tract leading from the soft tissue collection to the lateral skin surface. Coronal T1 fat-saturated imaging after intravenous contrast administration (Fig. 3) showed the peripherally enhancing fluid collection and sinus tract. It also revealed enhancement in the humeral head corresponding to the area of edema.

Differential Diagnosis

Chronic Osteomyelitis (Bacterial, Fungal, Mycobacterial)

Bone Metastases from a Primary Malignancy

The patient was taken to the operating room where the remainder of the humeral head was excised. Tissue was sent for histologic and microbiologic analyses (Fig. 4).

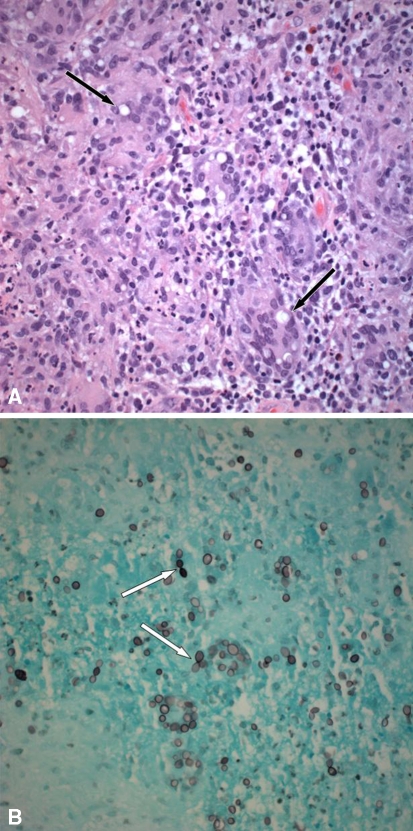

Fig. 4A–B.

(A) A representative section from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue shows an intense granulomatous reaction with numerous multinucleated giant cells containing large uninucleate yeasts (thin black arrow) (Stain, hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification, ×400). (B) A GMS stain highlights large ovoid yeasts in the cytoplasm of multinucleated giant cells. Narrow-based budding is seen with a figure-of-eight configuration (thin white arrow) (Original magnification, ×400).

Based on the history, physical examination, laboratory tests, imaging studies, and histologic picture, what is the diagnosis and how should the patient be treated?

Histology Interpretation

Designated as left humeral head tissue, several irregular fragments of red-tan bone and soft tissue aggregating 3 cm in greatest dimension were received for pathologic examination. Permanent hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections of the left humeral head tissue showed an intense granulomatous inflammatory reaction of the soft tissue with accompanying granulation tissue and focal necrosis. In the cytoplasm of the multinucleated giant cells, yeast was seen by hematoxylin and eosin stain, ranging in diameter from 8 to 15 μm (Fig. 4A). Hyphal forms were not present. Grocott methenamine silver (GMS) stain, for detection of fungi, highlighted large round-to-oval uninucleate yeasts with thick walls and narrow-based budding (figure-of-eight forms) (Fig. 4B). The adjacent bone showed chronic osteomyelitis with bone destruction and focal necrosis. These morphologic findings supported a diagnosis of Histoplasma capsulatum var. duboisii. A DNA probe for this organism was performed at a reference laboratory and was confirmatory.

Diagnosis

Chronic fungal osteomyelitis attributable to Histoplasma capsulatum var. duboisii.

Discussion and Treatment

The patient presented with chronic pain and fistulous drainage of the left proximal arm and was diagnosed with chronic osteomyelitis. The causative organism was found to be Histoplasma capsulatum var. duboisii by pathologic and microbiologic evaluations. This patient’s history is consistent with the diagnosis owing to her epidemiologic exposure risk (living in western Africa); the lack of major systemic illness; the pathologic findings of thick-walled yeast cells, narrow-based budding, and granulomatous changes; and the positive DNA probe.

The clinical course and MRI findings were indicative of chronic osteomyelitis. Chronic osteomyelitis often presents with subtle symptoms and few laboratory abnormalities. This patient had low-grade fevers, night sweats, and moderately elevated ESR and CRP. The peripherally enhancing fluid signal in the surgical cavity with a fistulous tract extending to the skin surface is pathognomonic for an abscess with fistulous drainage whereas the enhancing high signal in the humeral head was highly concerning for osteomyelitis. Bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus and gram-negative bacilli can cause chronic osteomyelitis, but these organisms were not seen on the Gram’s stain nor were they cultured in standard bacterial media. Other fungal etiologies that were considered included Candida albicans and Blastomyces dermatitidis. Candida albicans has a different histologic appearance and grows readily on standard bacterial growth media. Blastomyces dermatitidis has a similar yeast size to that of Histoplasma capsulatum var. duboisii; however, it exhibits broad-based budding and contains multiple nuclei, features that were not seen on the pathologic specimen, and it is not found in either western Africa or Colorado. Mycobacteria such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycobacterium africanum, and Mycobacterium abscessus may cause chronic osteomyelitis and fistulous tracts, and they also cause a similar granulomatous inflammation on histology. A negative tuberculin skin test is not sufficient for exclusion of this diagnosis, as approximately 30% of patients with active tuberculosis may have a negative tuberculin skin test (ie, anergy) [2]. Specimens are rarely smear-positive for acid fast bacilli (AFB) and the diagnosis typically is made through AFB cultures; AFB cultures of this patient’s surgical specimen were negative. Metastases to bone from a primary malignancy (eg, breast, thyroid, renal cell, or lung cancer) may present this way but more typically cause pain and/or a pathologic fracture. Plain film of the humerus was potentially suggestive of a bone malignancy because extraarticular osteomyelitis is relatively rare in adults unless there is direct spread from a soft tissue ulcer or from penetrating trauma. However, the diagnosis would have been made based on pathologic analysis and likely would have caused more rapid progression than this patient’s indolent 3-year course.

Histoplasma capsulatum was discovered in 1905 by a pathologist in Panama, Dr. Samuel Darling. While performing autopsies on patients who presumably had died of miliary tuberculosis, he observed numerous small intracellular bodies. These initially were thought to be protozoa but later were reclassified as yeast. Histoplasma capsulatum was first grown in the laboratory in the 1920s. It survives as a mold at room temperature and as a yeast at 37°C. Histoplasma capsulatum (ie, classic histoplasmosis) yeast cells are 3 to 5 μm in diameter whereas Histoplasma capsulatum var. duboisii (ie, African histoplasmosis) yeast cells are 8 to 15 μm in diameter. The mold is characterized by microconidia and macroconidia [1].

African histoplasmosis is found in western Africa, central Africa, and Madagascar. The transmission of this particular mold is unclear, although outbreaks have been associated with proximity to chicken runs and bat caves. Some postulate African histoplasmosis is transmitted through insect bites whereas others assert it is inhaled in a similar manner to classic histoplasmosis [3].

African histoplasmosis usually involves the skin, subcutaneous tissue, lymph nodes, and bones. Skin manifestations include a papular, nodular, ulcerative, eczematous, or psoriatic pattern. Osteomyelitis attributable to African histoplasmosis usually has an osteolytic pattern on plain radiographs, and it is common to have multiple bones involved. The most common sites of involvement are the skull, ribs, vertebrae, femur, humerus, tibia, and wrist bones. Involvement of internal organs and the central nervous system (CNS) is possible although rare [3].

The treatment of severe African histoplasmosis (ie, internal organ, CNS, multiple bone or skin lesions) is amphotericin B (1 mg/kg daily). Less severe and single-site cases may be treated with oral itraconazole (200 mg/kg twice daily) or fluconazole. Itraconazole can have poor absorption. The liquid formulation is preferred for better absorption, and drug levels must be checked to ensure they are therapeutic [4, 5]. Anecdotally, most lesions associated with African histoplasmosis are surgically débrided and treated with antifungal agents, although no randomized controlled trials exist to compare combined medical and surgical treatment with medical therapy alone.

Our patient was started on itraconazole liquid after surgical debridement, but the medication failed to absorb and the patient had an undetectable drug level. The patient was transitioned to oral fluconazole. She responded clinically with closure of the fistula and has tolerated a 12-month course of fluconazole. There are no published reports to guide the decision and timing regarding implanting a prosthetic joint after treatment. In our case, the orthopaedic surgeon does not plan to place a prosthetic joint because the patient’s functional status is acceptable and stable.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Robert Belknap for his roles in managing the patient and editing this manuscript.

Footnotes

The institution of the author (HY) has received funding from the Larrk Foundation. The remaining authors (ST, AS, TJ) certify that he or she has no commercial associations that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

Each author certifies that his or her institution waived or does not require approval for the reporting of this case and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

The work was performed at Denver Health Medical Center.

References

- 1.Deepe GS. Histoplasma capsulatum. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, editors. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2010. pp. 3305–3318. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diel R, Loddenkemper R, Nienhaus A. Evidence-based comparison of commercial interferon-gamma release assays for detecting active tuberculosis: a metaanalysis. Chest. 2010;137:952–968. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-2350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gugnani HC, Muotoe-Okafor F. African histoplasmosis: a review. Rev Iberoam Micol. 1997;14:155–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lortholary O, Denning DW, Dupont B. Endemic mycoses: a treatment update. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999;43:321–331. doi: 10.1093/jac/43.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wheat LJ, Freifeld AG, Kleiman MB, Baddley JW, McKinsey DS, Loyd JE. Kauffman CA; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:807–825. doi: 10.1086/521259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]