Abstract

Background

Short-term studies report comparable complication rates of one-stage bilateral versus two-stage procedures in hip resurfacing, although the long-term effects of such procedures on survivorship, quality of life, and disease-specific scores are currently unknown.

Questions/purposes

We compared clinical scores, length of stay, complication rates, and survivorship in patients who underwent bilateral hip resurfacing grouped on the basis of one-stage versus two-stage operation.

Patients and Methods

We retrospectively reviewed 75 patients who underwent a one-stage procedure and 87 patients who had both hips resurfaced in separate procedures. The demographics and etiologies were similar for the two groups. The mean followup time was longer in the two-stage group (7.3 years; range, 2.6–12.3 years) than in the one-stage group (6.6 years; range, 2.6–10.9 years).

Results

We found no differences in the latest postoperative UCLA pain, walking function, and activity scores; Harris hip scores; or SF-12 scores between the two groups. The average length of stay was shorter for the one-stage group. The early complication rates were similar between the two groups. One-stage patients had a higher revision rate than the patients in the two-stage group (14 versus four hips, respectively), but this was not true for patients with femoral components 48 mm or greater in size.

Conclusions

We found a greater rate of revisions in the one-stage group, suggesting possible long-term detrimental effects of the one-stage procedure. Our data suggest selecting patients with large component sizes if the surgeries are to be performed under one anesthesia.

Level of Evidence

Level III, therapeutic study. See Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

Several authors have previously reported short-term findings in one-stage bilateral THA performed at the same anesthetic setting [20, 25]. In comparison to two-stage bilateral THA, a one-stage procedure decreases total duration of recovery, reduces total hospital stay (and resulting in lower cost) [21], and provides similar pain relief [1] with possibly a greater ROM gain and walking ability for patients with very stiff hips [9]. However, patient selection is important, because there is also a higher risk of pulmonary [7] or cardiovascular complications [16, 23]. Only one of these studies has addressed the potential long-term effect of one-stage bilateral procedures on the survivorship of the devices and found no difference between simultaneous bilateral and unilateral procedures with a followup as long as 27 years [7].

Hip resurfacing, as an alternative to THA, is a procedure commonly used in younger patients as shown by the mean age at surgery from reports of large series [3, 6, 8, 11, 13, 19, 22, 24]. One short-term study in patients with good bone quality reported no difference in early postoperative complication rates between one-stage and two-stage procedures [17]. However, another report speculated one-stage bilateral hip resurfacing may present a greater risk of femoral neck fracture [15] essentially because of the possible trauma inflicted by the second surgery on the site of the first resurfacing. Even after the cement has cured, the freshly reamed bone is still healing and additional stresses directed perpendicular to the general direction of the trabeculae could compromise the initial fixation of the femoral component. In addition, small femoral component sizes have been associated with failure of hip resurfacing [5, 11, 18] and this may also limit the appropriateness of single-stage bilateral resurfacing because of the combination of a smaller area available for fixation and the additional stresses of the bilateral procedure. Thus, the relative advantages or disadvantages of single-stage versus two-stage hip resurfacing are unclear.

We asked whether patients undergoing one-stage bilateral hip resurfacing differ from patients having a two-stage operation with regard to (1) quality of life and disease-specific scores; (2) length of hospital stay; (3) complication rate; (4) survivorship of the procedure; and (5) whether any differences in survivorship would remain independent from the component size used.

Patients and Methods

We retrospectively reviewed all 75 patients who had one-stage bilateral hip resurfacing (ie, both procedures performed under the same anesthetic) between 1996 and 2006. For comparison, we selected all 87 patients who had two-stage bilateral hip resurfacing during the same period. We included all patients regardless of indications for the surgery, gender, component size, or bone stock deficiencies. The decision to perform one- or two-stage bilateral hip resurfacings was made by the senior author (HCA) and the patient who understood the risks. The indications for a one-stage procedure included severe degree of disability (both hips had to have symptomatic osteoarthritis) and young or middle age. Initially, one-stage patients had to be younger than 55 years with a body mass index less than 30 kg/m2; however, as the senior author became more comfortable with one-stage bilateral resurfacing, the patient group broadened. Proximity to our center was a factor for many; patients with severe bilateral osteoarthritis who lived out of state were more likely to have a one-stage procedure to minimize long-distance travel for staged procedures. None of our patients presented medical comorbidities that could preclude performing simultaneous or staged procedures. Two patients died of causes not related to the surgery, one 21 months after one-stage surgery (accidental drowning) and the other 83 months after his left hip operation and 79 months after the right. The average time between the two surgeries in the two-stage group was 30.4 months (range, 1–95 months). The average followup was similar between the two groups: 6.6 years (range, 2.6–10.9 years) for the one-stage group and 7.3.years (range, 2.6–12.3 years) for the two-stage group. The average age at surgery was 49.4 years (range, 25–68 years) in the one-stage group and 51.7 years (range, 16–76 years) in the two-stage group (Table 1). However, the average age of the patients of the two-stage group at the time of their first surgery was 50.4 years (range, 16–76 years). The patient body mass index was 26.8 kg/m2 (range, 19–43 kg/m2) in the one-stage group and 27.3 kg/m2 (range, 17–36 kg/m2) in the two-stage group. Fifty-seven patients (76.0%) were male in the one-stage group versus 70 (80.5%) in the two-stage group. The diagnosis was “primary” osteoarthritis in 52 hips (65%) in the one-stage group and 34 hips (57%) in the two-stage group. There were no differences in gender (p = 0.75) or diagnosis (p = 0.39) between the two groups. There was no difference (p = 0.59) in the prevalence of hips with femoral defects greater than 1 cm between the two groups (38.7% for the one-stage group and 35.1% for the two-stage group). The preoperative UCLA hip scores (assessed before the first operation for the two-stage group) were higher (less disabled) in the two-stage group for pain (mean, 3.6 versus 3.3; p = 0.05), walking (mean, 6.4 versus 5.9; p = 0.01), function (mean, 5.9 versus 5.3; p = 0.01), and activity (mean, 4.8 versus 4.3; p = 0.01).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics between groups

| Characteristic | One-stage group | 95% CI | Two-stage group | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)* | 49.4 (25–68) | 1.44 | 51.7 (16–76) | 1.58 |

| BMI (kg/m2)* | 26.8 (19–43) | 0.67 | 27.3 (17–36) | 0.57 |

| Femoral component size (mm)* | 47.4 (36–54) | 0.58 | 47.6 (36–54) | 0.57 |

| Male/female ratio | 76%/24% | 80%/20% | ||

| Diagnosis | ||||

| Osteoarthritis | 74.7% | 77.0% | ||

| Osteonecrosis | 8.0% | 9.2% | ||

| Developmental hip dysplasia | 8.0% | 9.2% | ||

| Other | 9.3% | 4.6% | ||

| Femoral defects > 1 cm | 38.7% | 35.1% | ||

* Values are expressed as means with ranges in parentheses; CI = confidence interval; BMI = body mass index.

A sample size of 63 subjects per group was determined sufficient to detect differences of 5 points on the SF-12 scores with a power of 80% and alpha level set at 0.05. This number was also sufficient for detection of meaningful differences with the other scores used in the study.

All procedures were performed by the senior author (HCA) using the Conserve®Plus metal-on-metal hip resurfacing system (Wright Medical Technology Inc, Arlington, TN). The surgical technique for hip resurfacing has been described elsewhere [2]. All procedures were performed in the lateral decubitus position using the posterior approach. Epidural supplemented by general anesthesia was used, and a cell saver was used in the one-stage bilateral cases. A Hemovac® drain was inserted subfascially and discontinued after 24 hours. All patients had prophylactic intravenous antibiotics before, during, and for approximately 1 day after surgery. After performing one side, the patient was turned in the operating room, and the other side was operated on using the same sterile setup.

Postoperatively, one-stage patients were ambulatory with a four-point gait, weightbearing as tolerated with assistive devices for 4 to 6 weeks, whereas the two-stage group patients used a three-point gait (50% weightbearing) for a similar period. In both groups, mobilization started 1 day after surgery. Otherwise, the rehabilitation protocol was similar for both groups with physical therapy prescribed and supervised three times per week for 1 month and then once a week for the next month. In these sessions, the patients were given simple bent-knee flexion, isometric knee extension, and hip extension exercises. The patients were allowed to return to all activities by 3 months and impact sports at 6 months.

Complications and length of hospitalization were recorded. The patients were followed prospectively at 6 weeks, 4 months, and yearly thereafter. UCLA hip scores [4], Harris hip scores [12], and SF-12 health survey [26] scores were calculated at followup visits. Hip ROM values (flexion, flexion contracture, abduction, adduction, internal rotation, and external rotation) were recorded. Plain radiographs (AP pelvis and crosstable lateral [14]) were evaluated by the senior investigator.

The Mann-Whitney U test was used between groups for differences in UCLA hip scores. We determined differences in Harris hip score and SF-12 scores using Student’s t-test for independent samples. Chi square computations were used to compare groups in prevalence of large (greater than 1 cm) femoral head defects, gender, diagnosis, and complication rates. Comparative time-dependent survivorship analyses between the two groups were performed using the time to revision for any reason as end point. The log-rank test was used to compare the survivorship curves of the two groups. These comparisons were first carried out on the entire group of patients and then on the subset of patients with femoral components 48 mm or greater in size. Statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft® Excel® XP (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA) and Stata® statistical software package (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Results

We found no difference between the two groups in the mean clinical scores at the last followup (Table 2). ROM was also comparable between the one- and two-stage groups with mean respective values of 120.5° versus 123.1° (p = 0.14) for the flexion arc, 73.7° versus 70.8° (p = 0.06) for the abduction-adduction arc in extension, and 76.9° versus 75.8° (p = 0.60) for the rotation arc in extension.

Table 2.

Summary of the postoperative clinical scores for the two groups

| Score | One-stage group | Two-stage group | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| UCLA hip scoring system | |||

| Pain | 9.5 (7–10) | 9.5 (7–10) | 0.63 |

| Walking | 9.8 (8–10) | 9.8 (7–10) | 0.41 |

| Function | 9.6 (4–10) | 9.7 (6–10) | 0.24 |

| Activity | 7.6 (3–10) | 7.6 (3–10) | 0.93 |

| SF-12 health survey | |||

| Physical component | 52.4 (20.6–62.1) | 51.2 (27.1–61.5) | 0.30 |

| Mental component | 51.4 (10.5–63.7) | 53.2 (19.8–64.1) | 0.09 |

| Harris hip score | 93.4 (53–100) | 94.8 (52–100) | 0.16 |

Values are expressed as means with ranges in parentheses.

The total length of hospitalization for both hips was greater (p = 0.001) for the patients having two operations; the one-stage patients averaged a hospital stay of 4.7 days (range, 2–21 days) compared with a total of 7.8 days (range, 4–17 days) in the two-stage patients.

Nine patients had complications that did not require the revision of components, five in the one-stage group and four in the two-stage group. These complications included four femoral nerve palsies (two in each group), one peroneal nerve palsy associated with a common femoral artery thrombus (one-stage group), three dislocations (one in the one-stage group, two in the two-stage group), and one reexploration of the hip 1 day after surgery to remove bone debris trapped in the joint (one-stage group). All complications resolved and there have been no recurrent dislocations. However, the patient with the common femoral artery thrombus developed compartment syndrome for which he underwent a surgical release and now has neurogenic pain and a drop foot. This adverse event was attributed to the use of an unsatisfactory anterior pelvic stabilizer that may have applied excessive pressure on the femoral triangle [3]. Fourteen hips were revised in the one-stage group with a mean time to revision of 56.0 months (range, 3 days to 111 months) and four in the two-stage group with a mean time to revision of 60.8 months (range, 13–103 months) (Table 3). One patient was revised when the socket protruded through the acetabular wall on the third day after surgery and required acetabular component revision in combination with bone grafting. Overreaming of the first hip in combination with a one-stage procedure may have resulted in this failure. However, the main cause for revision in both groups was femoral loosening (Table 3). There was only one case of femoral loosening in a hip with good bone quality (cysts less than 1 cm) and one in a patient with a component size of more than 46 mm. There were four neck fractures in the one-stage group and none in the two-stage group, one early 3 months after surgery and three late (20 and 50 months in one patient with fibromyalgia, 31 months in another).

Table 3.

Modes of failure and demographics of the hips that underwent revision surgery

| Identification number | Age (years) | Etiology | Date of surgery | Time to revision (months) | Mode of failure | Head size (mm) | Body mass index | Surface arthroplasty risk index | Femoral head defects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One-stage procedures | |||||||||

| 206 (left) | 31.3 | Legg-Calvé-Perthes | 11/10/99 | 54.7 | Femoral loosening | 46 | 23.9 | 5 | > 1 cm |

| 207 (right) | 31.3 | Legg-Calvé-Perthes | 11/10/99 | 54.7 | Femoral loosening | 46 | 23.9 | 5 | > 1 cm |

| 217 | 51.6 | Osteoarthritis | 12/3/99 | 111.4 | Femoral loosening | 38 | 26.6 | 5 | > 1 cm |

| 218 | 51.6 | Osteoarthritis | 12/3/99 | 98.7 | Femoral loosening | 38 | 26.6 | 3 | < 1 cm |

| 246 | 39.3 | Inflammatory osteoarthritis | 1/20/00 | 39.1 | Femoral loosening | 42 | 24.2 | 3 | None |

| 274 (right) | 61.1 | Osteoarthritis | 2/17/00 | 50.0 | Femoral neck fracture | 44 | 27.0 | 2 | None |

| 275 (left) | 61.1 | Osteoarthritis | 2/17/00 | 20.1 | Femoral neck fracture | 46 | 27.0 | 2 | None |

| 294 (right) | 43.9 | Osteoarthritis | 3/23/00 | 85.0 | Wear related | 40 | 20.3 | 3 | < 1 cm |

| 295 (left) | 43.9 | Osteoarthritis | 3/23/00 | 96.7 | Wear related | 42 | 20.3 | 3 | < 1 cm |

| 314 | 45.8 | Osteonecrosis | 4/24/00 | 3 days | Acetabular component protrusio | 50 | 31.0 | 2 | > 1 cm |

| 524 | 51.3 | Osteoarthritis | 4/11/02 | 82.8 | Femoral loosening | 44 | 22.5 | 5 | > 1 cm |

| 525 | 51.3 | Osteoarthritis | 4/11/02 | 55.0 | Femoral loosening | 44 | 22.5 | 3 | > 1 cm |

| 584 | 52.4 | Osteoarthritis | 1/10/03 | 31.7 | Femoral neck fracture | 50 | 28.8 | 2 | > 1 cm |

| 746 | 49.1 | Osteoarthritis | 12/14/04 | 2.1 | Femoral neck fracture | 50 | 28.0 | 0 | None |

| Two-stage procedures | |||||||||

| 25 | 49.0 | Osteonecrosis | 7/8/97 | 61.7 | Femoral loosening | 40 | 28.5 | 4 | > 1 cm |

| 53 | 51.4 | Osteoarthritis | 4/28/98 | 103.4 | Femoral loosening | 50 | 27.2 | 3 | > 1 cm |

| 111 | 66.5 | Osteoarthritis | 1/29/99 | 65.1 | Femoral loosening | 46 | 22.7 | 5 | > 1 cm |

| 718 | 47.4 | Osteoarthritis | 9/7/04 | 13.1 | Sepsis | 48 | 25.7 | 1 | < 1 cm |

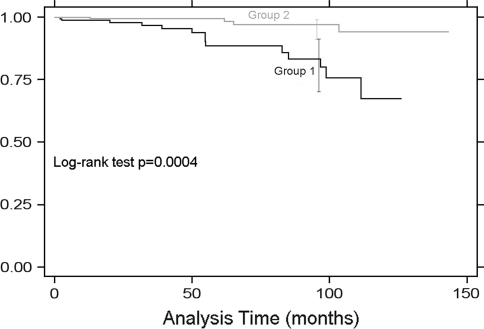

Using the time to revision for any reason as the end point, the 8-year survivorship of the one-stage group was lower (p < 0.001) in the two-stage group: 83.1% (95% confidence interval, 70.0%–90.9%), whereas the 8-year survivorship of the two-stage group was 97.0% (95% confidence interval, 90.5%–99.1%) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier survivorship curves of the one- and two-stage groups using the time to revision for any reason as the end point show the 8-year survivorship of the one-stage group (83.1%; 95% confidence interval, 70.0%–90.9%) was lower (log-rank test, p = 0.0004) than that of the two-stage group (97.0%; 95% confidence interval, 90.5%–99.1%).

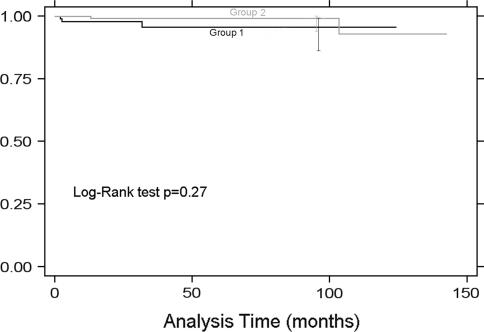

A similar analysis performed on hips resurfaced with a femoral component 48 mm or greater in outside diameter yielded 8-year survival estimates of 95.5% (95% confidence interval, 85.8%–98.7%) for the one-stage group and 99.1% (95% confidence interval, 93.7%–99.9%) for the two-stage group (log-rank test, p = 0.27) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier survivorship curves of the one-stage and two-stage groups in hips resurfaced with a femoral component 48 mm or greater in outside diameter using the time to revision for any reason as the end point yielded similar 8-year survival estimates for the one-stage group (95.5%; 95% confidence interval, 85.8%–98.7%) and for the two-stage group (99.1%; 95% confidence interval, 93.7%–99.9%) (log-rank test, p = 0.2737).

Discussion

Comparative studies between one-stage and two-stage bilateral conventional THA are abundant in the literature [25]. However, only a similar short-term report has been published related to hip resurfacing [17]. Data are needed to determine longer-term efficacy of one-stage operations and define indications and pitfalls related to this procedure. The present study compared clinical scores, length of stay, complication rates, and survivorship in patients who underwent one-stage versus two-stage hip resurfacing with a 2- to 12-year followup.

We recognize limitations of our study. First, the actual economic benefits of one-stage versus two-stage procedures were not measured directly because these data were not available at our institution. We presume a cost–benefit based on the reduction in hospital length of stay. However, billing and reimbursement rates greatly vary between institutions and insurance providers and these data usually do not allow generalizations. Second, the study is retrospective in nature with no randomization of the subjects between groups, but all bilateral procedures performed within the study time were included and the basis for the decision to perform one-stage versus two-stage surgery was essentially the presence of end-stage bilateral disease and the distance to our center from the patient’s home (the greater the distance, the more benefits to a one-stage operation). These two selection criteria, we believe, do not constitute biases that could potentially invalidate our results. Third, the optimal timing of a two-stage procedure would be useful to surgeons performing bilateral resurfacing but this was beyond the scope of our study design and not addressed in the present study. Further data and followup of our patients would be needed to provide this information.

We found one-stage bilateral hip resurfacing was associated with similar hip ROM, UCLA activity score, SF-12, or Harris hip scores compared with two-stage resurfacing at a minimum 2-year followup with no increase in short-term complications. These findings confirm those of McBryde et al. [17] of one-stage bilateral hip resurfacing compared with two-stage procedures at 1-year followup. The authors reported no difference in postoperative complications between the two groups of patients. However, in no instance in our study did the medical condition of the patient after the first hip resurfacing result in aborting the second procedure as described in the previously cited report [17]. In retrospect, the second surgery of the patient who sustained the cup protrusio should have been postponed and the patient placed on nonweightbearing precautions, which could have possibly prevented the need for revision. Our findings are also similar to those reporting conventional THAs, which showed comparable pain relief scores between groups [1, 7, 9, 20, 25] and similar complication rates [1, 9, 25] (Table 4). In contrast, Parvizi et al. found more wound drainage and anemia in their two-stage group [20], whereas two other studies highlighted a greater risk for major complications (pulmonary or cardiovascular) associated with one-stage procedures [23].

Table 4.

One-stage versus two-stage hip arthroplasty: comparative table of the data reported in the literature

| Author | Number of patients | Mean followup (years) | Prosthetic type | Clinical scores | Hospital stay | Complications | Survivorship |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| McBryde et al. [18] | 37 one-stage, 55 two-stage | 1.25 one-stage, 2.83 two-stage | Resurfacing | Comparable after 1.5 years | Shorter for one-stage group | No difference | Not reported |

| Tsiridis et al. [25] | 2063 one-stage | N/A (review—meta-analysis) | THA | No difference | Shorter for one-stage group | No difference | Not reported |

| Parvizi et al. [20] | 98 one-stage, 98 two-stage | Not reported | THA | No difference | Shorter for one-stage group | More anemia and wound drainage in two-stage group | Not reported |

| Reuben et al. [21] | 7 one-stage, 8 two-stage | Not reported | THA | Not reported | Shorter for one-stage group | Not reported | Not reported |

| Alfaro-Adrian et al. [1] | 95 one-stage, 107 two-stage | Not reported | THA | No difference | Shorter for one-stage group | No difference | Survivorship not reported but no difference in revision rate |

| Eggli et al. [9] | 64 one-stage, 191 two-stage | 1.5 years | THA | No difference in pain relief but better walking for one-stage | Shorter for one-stage group | No difference | Not reported |

| Berend et al. [7] | 450 one-stage, 450 unilateral | Not reported—up to 27 years | THA | No difference | Not reported | Greater rate of pulmonary complications in one-stage group | No difference |

| Swanson et al. [23] | 400 one-stage, 400 unilateral | Not reported | THA | Not reported | Not reported | Greater rate of major complications/patient in one-stage group but only a trend per hip | Not reported |

| Amstutz et al. [current study] | 75 one-stage, 87 two-stage | 6.4 one-stage, 7.1 two-stage | Resurfacing | Comparable at last followup | Shorter for one-stage group | No difference | Better for two-stage group |

N/A = not available.

Our patients with one-stage bilateral surgery had a shorter length of stay (4.7 days) as compared with the two-stage patients (7.9 days), a result corroborated by all comparable studies, including all prosthetic types [1, 9, 17, 20, 21, 25]. This should lead to substantial cost savings to healthcare payers. The shorter hospitalization and overall recovery time should translate into less time off work, resulting in further economic benefit. In addition, there is the benefit of undergoing only one postoperative recovery.

We found more revisions in the one-stage group (14 of 150 versus four of 174 for the two-stage group). This was in contrast with the findings of Berend et al. who found no difference in the long-term survivorship of conventional THA [7]. We speculate a one-stage bilateral hip resurfacing procedure may place more stresses on the implants both during the surgical procedure and the recovery phase with less ability for the patient to protect the operated limb from excessive weightbearing in the postoperative period. This could bear more importance in hips with risk factors such as large cysts and small component size. There is also a possibility that other factors not measured in our study such as bone mineral density may have had a greater influence on the outcome of one group than the other. Our analysis indicated component size was related to the rate of revision in this cohort of patients having bilateral surgery, which confirms previous results from large series of hip resurfacing [3, 10]. For the hips resurfaced with a component size of 48 mm or greater (which constitutes the majority of the patients seeking hip resurfacing), we found no difference between one- and two-stage groups, and the survivorship results at 8 years were greater than 95%, which is comparable to most conventional THA results.

However, at this point, and in light of our data, we cannot recommend one-stage bilateral resurfacing for surgeons and their patients, at least until the technical factors that made resurfacing more prone to failure in our early cases have been eliminated. A large experience in resurfacing is required should a surgeon elect to proceed with this procedure as a result of patient choice or level of disability, and candidates for one-stage bilateral resurfacings should be selected on the basis of their templated component size (greater than 46 mm). In addition to the surgeon optimizing his or her technique and confidence in the procedure, there is another advantage in delaying the surgery on the second hip because of the possibility that new techniques and technology will arise during that time because the modern generation of hip resurfacing designs are still in evolution.

We believe in general bilateral hip resurfacing is better performed in two separate surgical settings, especially with risk factors of small component size and large cysts despite the comparable clinical outcomes and the advantages of a decrease in length of hospitalization, recovery time, and the associated cost savings of a one-stage procedure. Mid- to long-term data from other large series in which both procedures have been performed are needed to determine the overall benefits of the one-stage procedures.

Footnotes

One of the authors (HCA) has received research funding from St Vincent Medical Center (Los Angeles, CA) and Wright Medical Technology, Inc (Arlington, TN); one of the authors (HCA) certifies that he has or may receive payments or benefits from a commercial entity (Wright Medical Technology) related to this work.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

This work was performed at the Joint Replacement Institute, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

References

- 1.Alfaro-Adrian J, Bayona F, Rech JA, Murray DW. One- or two-stage bilateral total hip replacement. J Arthroplasty. 1999;14:439–445. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(99)90099-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amstutz H, Beaulé P, Dorey F, Le Duff M, Campbell P, Gruen T. Metal-on-metal hybrid surface arthroplasty—surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(Suppl 1):234–249. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amstutz H, Le Duff M. Eleven years of experience with metal-on-metal hybrid hip resurfacing: a review of 1000 Conserve Plus. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23(Suppl 1):36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amstutz H, Thomas B, Jinnah R, Kim W, Grogan T, Yale C. Treatment of primary osteoarthritis of the hip. A comparison of total joint and surface replacement arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66:228–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amstutz H, Wisk L, Le Duff M. Sex as a patient selection criterion for metal-on-metal hip resurfacing arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2010 May 7 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Back D, Dalziel R, Young D, Shimmin A. Early results of primary Birmingham hip resurfacings. An independent prospective study of the first 230 hips. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:324–329. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B3.15556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berend M, Ritter M, Harty L, Davis K, Keating E, Meding J, Thong A. Simultaneous bilateral versus unilateral total hip arthroplasty an outcomes analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:421–426. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.09.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smet K. Belgium experience with metal-on-metal surface arthroplasty. Orthop Clin North Am. 2005;36:203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eggli S, Huckell CB, Ganz R. Bilateral total hip arhroplasty; one stage versus two stage procedure. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;328:108–118. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199607000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graves S. Annual Report. Australian Orthopaedic Association—National Joint Replacement Registry. Adelaide, Australia: AOA; 2008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Graves S. Annual Report. Australian Orthopaedic Association—National Joint Replacement Registry. Adelaide, Australia: AOA; 2009. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Harris W. Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: treatment by mold arthroplasty. An end-result study using a new method of result evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1969;51:737–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jameson S, Langton D, Nargol A. Articular surface replacement of the hip: a prospective single-surgeon series. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92:28–37. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B1.22769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson CR. A new method for roentgenographic examination of the upper end of the femur. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1932;14:859–866. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Little C, Ruiz A, Harding I, McLardy-Smith P, Gundle R, Murray D, Athanasou N. Osteonecrosis in retrieved femoral heads after failed resurfacing arthroplasty of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:320–323. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Macaulay W, Salvati E, Sculco T, Pellicci P. Single-stage bilateral total hip arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2002;10:217–221. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200205000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McBryde C, Dehne K, Pearson A, Treacy R, Pynsent P. One- or two-stage bilateral metal-on-metal hip resurfacing arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:1144–1148. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B9.19107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McBryde C, Theivendran K, Thomas A, Treacy R, Pynsent P. The influence of head size and sex on the outcome of Birmingham hip resurfacing. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:107–112. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mont M, Seyler T, Ulrich S, Beaule P, Boyd H, Grecula M, Goldberg V, Kennedy W, Marker D, Schmalzried T, Sparling E, Vail T, Amstutz H. Effect of changing indications and techniques on total hip resurfacing. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;465:63–70. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e318159dd60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parvizi J, Pour A, Peak E, Sharkey P, Hozack W, Rothman R. One-stage bilateral total hip arthroplasty compared with unilateral total hip arthroplasty: a prospective study. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(Suppl 2):26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reuben J, Meyers S, Cox D, Elliott M, Watson M, Shim S. Cost comparison between bilateral simultaneous, staged, and unilateral total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13:172–179. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(98)90095-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stulberg B, Trier K, Naughton M, Zadzilka J. Results and lessons learned from a United States hip resurfacing investigational device exemption trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(Suppl 3):21–26. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swanson K, Valle A, Salvati E, Sculco T, Bottner F. Perioperative morbidity after single-stage bilateral total hip arthroplasty: a matched control study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;451:140–145. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000223992.34153.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Treacy R, McBryde C, Pynsent P. Birmingham hip resurfacing arthroplasty. A minimum follow-up of five years. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:167–170. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B2.15030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsiridis E, Pavlou G, Charity J, Tsiridis E, Gie G, West R. The safety and efficacy of bilateral simultaneous total hip replacement: an analysis of 2063 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:1005–1012. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B8.20552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller S. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]