Abstract

Introduction

The geometry of mastoid air cells system (MACS) has not been described for adults over a large range of MACS volumes.

Methods

Twenty subjects with a wide range of pneumatized MACS areas by X-rays had a CT scan of their middle ears and the MACS surface areas and volumes were reconstructed from serial sections using Image J.

Results

MACS volume varied from 0.7 to 21.4 ml and was linearly related to pneumatized area. Right and left MACS volumes and surface areas were highly correlated and MACS surface area was a linear function of volume.

Conclusions

MACS geometry as reflected in the relationship between surface area and volume is similar over a wide range of volumes. Given that surface area is related to the rate of gas exchange across the MACS mucosa, that rate is a direct linear function of MACS volume.

Keywords: Adults, Mastoid, Volume, Surface Area, CT

INTRODUCTION

The middle ear can be anatomically and functionally subdivided into two communicating airspaces, the tympanum and the mastoid air-cell system (MACS). Throughout, the middle ear is lined by a mucosa that embeds a network of blood vessels that provides for the metabolic requirements of the mucosa and also represents a source/sink for transmucosal gas exchange between the middle ear and local mucosal blood.

The tympanum is essentially a single, large air-cell that contains the middle ear ossicles which couple movements of the tympanic membrane to those of the round window and, thus, functions as the peripheral transducer organ for hearing. In contrast, the MACS is a multiply partitioned, cellular, air-space that increases middle ear volume, but does not participate directly in sound transduction. While the function of the MACS is debated,1 numerous studies show that MACS volume is indirectly related to the predisposition of the middle ear to certain pathological conditions including cholesteatoma and otitis media.2–6 One hypothesis advanced to explain this relationship is that the MACS functions as a middle ear gas reserve such that MEs with larger MACS require less frequent ET openings to maintain near-ambient total pressure.1

Using CT scans of human MEs with “normal” MACS volume, a previous study reconstructed the geometry of the MACS and reported a very high MACS surface area that was a linear function of MACS volume.7 MACS surface area for both diffusion-limited and perfusion-limited (assuming that blood perfusion is a function of surface area) is directly related to the rate of gas exchange across the MACS mucosa.8 This is one parameter that determines whether or not the MACS functions as a middle ear gas reserve. The purpose of the present study was to measure the surface area and volume for the MACS of adult humans over a wide range of volumes. The hypothesis tested is that the slope of the function relating MACS surface area to volume is different for smaller versus larger MACS volumes.

METHODS

The goal of this study was to measure the MACS surface area and volume over a wide range of MACS volumes. Twenty-eight adult subjects with and without a history of otitis media in childhood were recruited by advertisement, informed of the risks and benefits of study participation, and signed an institutionally approved informed consent. These subjects were then screened for entry by bilateral pneumatic otoscopy and tympanometry to document disease-free MEs and by taking bilateral middle ear x-ray’s in Schuller projection and measuring the pneumatized area for each MACS. Using those areas as estimates of MACS volume, the first 20 subjects with pneumatized areas evenly distributed across the expected range of values were selected for CT scanning (left ear: average=7.8±4.1, range=1.8–16.4 cm2; right ear: average=8.3±4.0, range=2.7–18.0 cm2; r=0.90 for the left vs. right pneumatized areas, p<.01). Eight subjects had pneumatized areas similar or identical to previously enrolled subjects and by protocol (which limited CT scanning to 20 subjects) were discontinued from study participation.

CT scans of the middle ear were done in the transverse plane at a resolution of .031 mm/pixel and a slice thickness of 0.63 mm using a GE LightSpeed VCT system (General Electric Health Care). From each CT scan, a set of transverse images through the bilateral MACS regions (superior to inferior) at 0.25 cm intervals was selected. Using Image J software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/), the images were imported and the left and right MACS regions were identified, segmented out and analyzed. For each image, the perimeter (cm) and area of all air-cells (cm2) were highlighted, measured and summed across images. These sums were multiplied by 0.25 cm (section interval) to yield MACS surface area (cm2) and volume (ml), respectively. This procedure is essentially identical to that used previously to measure MACS surface area and volume in adult subjects with “normal” MACS volumes.7 The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Pittsburgh.

All data were entered into Microsoft Excel for analysis. With the exception of the left MACS volume (p=.03; contains outlier), a normal distribution could not be rejected for all other variables, and therefore parametric statistics were used in the analyses. Linear regression was used to determine the relationships between: 1) MACS volume and the pneumatized area obtained from the Schuller projection x-ray; 2) right and left MACS volume, 3) right and left MACS surface area, and 4) MACS surface area and volume. The volume of right and left MACSs were highly correlated and, thus, the bilateral data provide potentially redundant information. Consequently, these analyses were done separately for the right and left MACS. The summary parameters for these regression analyses are reported in the Table. Because the left MACS of one subject (#13, 40 year old, male without a history of otitis media) represented an outlier for all relationships, the data reported in the Table include the results for the analyses on the full data set for the left and right MACS separately and also on a restricted data set for the left MACS that excluded the outlier. Between-group comparisons were done using a Student’s t test. In the text, the format average±standard deviation is used to summarize the data while, in the Table, the regression parameters and their standard errors are reported.

Table 1.

Sample Size (N), Slope (and Standard Error), Intercept (and Standard Error), the Square of the Pearson Product Moment Correlation Coefficient (R2) and the P-value for a Student’s t test Evaluating the Significance of a non-zero Slope Calculated by Least-Squares Linear Regression Analysis for Each Tested Relationship

| Relationship | N | Slope | Std Err | Intercept | Std Err | R2 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left MACS Volume vs Schuller Area | 20 | 0.67 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 2.11 | 0.31 | 0.01 |

| Left MACS Volume vs Schuller Area* | 19 | 0.67 | 0.14 | −0.20 | 1.20 | 0.58 | <.01 |

| Right MACS Volume vs Schuller Area | 20 | 0.62 | 0.11 | −0.18 | 1.02 | 0.62 | <.01 |

| Right vs Left MACS Volume | 20 | 0.59 | 0.10 | 2.20 | 0.71 | 0.66 | <.01 |

| Right vs Left MACS Volume* | 19 | 0.90 | 0.12 | 1.01 | 0.69 | 0.76 | <.01 |

| Right vs Left MACS Surface Area | 20 | 0.88 | 0.12 | 15.90 | 11.67 | 0.76 | <.01 |

| Right vs Left MACS Surface Area* | 19 | 0.89 | 0.11 | 12.30 | 11.13 | 0.80 | <.01 |

| Left MACS Surface Area vs Volume | 20 | 7.17 | 2.31 | 43.76 | 16.72 | 0.35 | 0.02 |

| Left MACS Surface Area vs Volume* | 19 | 15.90 | 1.30 | 2.02 | 8.54 | 0.89 | <.01 |

| Right MACS Surface Area vs Volume | 20 | 18.33 | 0.92 | −0.83 | 5.16 | 0.96 | <.01 |

MACS Volume=ml, MACS Surface Area=cm2, MACS Schuller Area=cm2

Analysis performed omitting the outlier data for the left ear of Subject 13

RESULTS

The study population consisted of 14 females and 6 males, aged 26.3±6.4 (range=20.4 to 40.5) years. All subjects were Caucasian. Six (30%) subjects reported a history of otitis media during childhood (4 had tympanostomy tubes inserted). For the 20 subjects, the average left and right MACS volumes were 5.5±4.9 (range=.7 to 21.4) and 5.5±3.6 (range 0.7 to 14.1) ml(paired Student’s t test, p=.96); surface areas were 82.8±59.8 (range=13.3 to 253.7) and 88.9±60.3 (range=13.3 to 256.4) cm2 (p=.37) and ratios of surface area to volume were 17.4±4.8 (range=3.2 to 24.4) and 16.7±3.7 (range=11.2 to 24.7) cm2/ml (p=.36), respectively.

The left and right MACS volumes were less for ears of subjects with a history of otitis media (left average=2.9±1.6 ml; right average=3.7±3.1 ml) when compared to those of subjects without a positive otitis media history (left average=6.6±5.5 ml, right average=6.2±3.6 ml), and the between-group differences under the directional hypothesis of greater MACS volume for ears of persons with a negative otitis media history approached statistical significance (1 tailed-Student’s t test, p=.06 and .07, respectively).

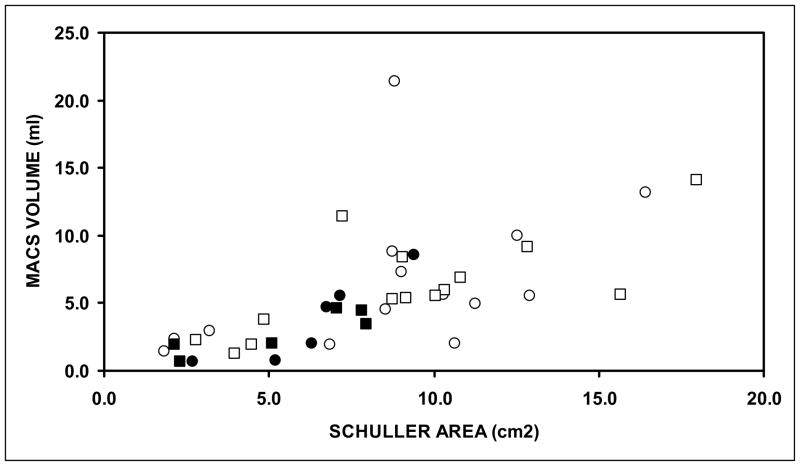

Figure 1 shows the MACS volume for the left and right ears of persons with and without a history of otitis media as a function of their respective pneumatized area based on Schuller projection x-rays. With the exception of a single outlier (Subject 13: left ear; 8.8 cm2, 21.4 ml), these relationships were approximately linear with 58% and 62% of the variance in left and right MACS volume explained by the regression on pneumatized area (See Table). There was no apparent effect of otitis media history on this relationship.

Figure 1.

MACS volume for the right (squares) and left (circles) ears of all study subjects as a function of the respective pneumatized area from Schuller projection x-rays. Filled symbols indicate ears of persons with a history of otitis media.

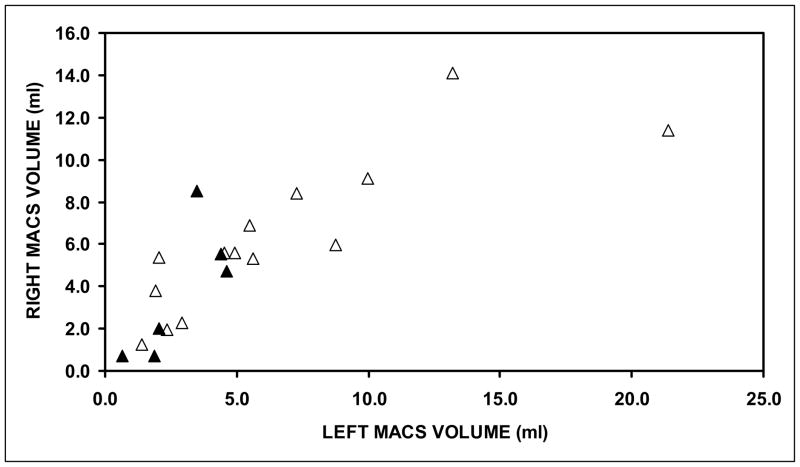

Figure 2 shows the right MACS volume for ears of persons with and without a history of otitis media as a function of their respective left MACS volume. With the exception of a single outlier (Subject 13: left ear=21.4 ml, right ear=11.4 ml), the relationship was linear with 76% of the variance in right MACS volume explained by the regression on left MACS volume (See Table). There was no apparent effect of otitis media history on this relationship.

Figure 2.

Right MACS volume as a function of the respective left MACS volume for ears from subjects with (filled triangles) and without (open triangles) a history of childhood otitis media.

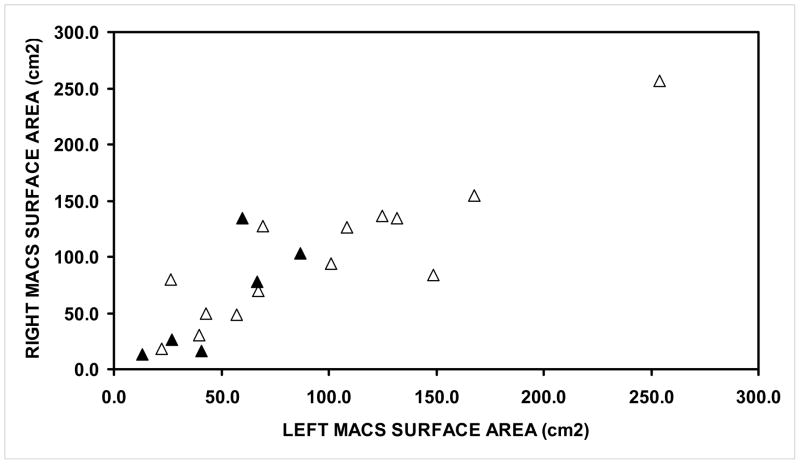

Figure 3 shows the right MACS surface area for ears of persons with and without a history of otitis media as a function of their left MACS surface area. The relationship was linear with 80% of the variance in right MACS surface area explained by the regression on left MACS surface area (See Table). There was no apparent effect of otitis media history on this relationship.

Figure 3.

Right MACS surface area as a function of the respective left MACS surface area for ears from subjects with (filled triangles) and without (open triangles) a history of childhood otitis media.

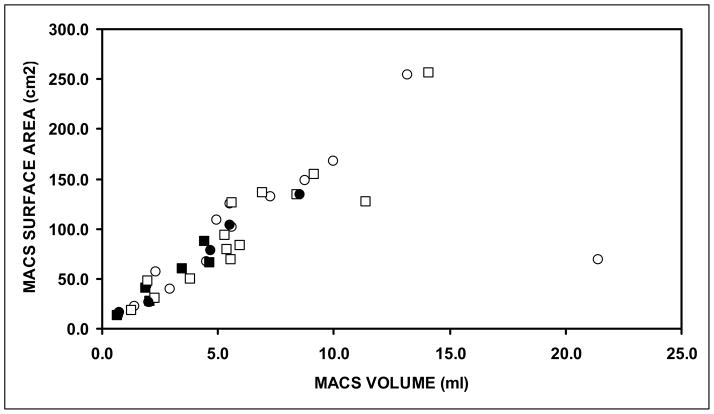

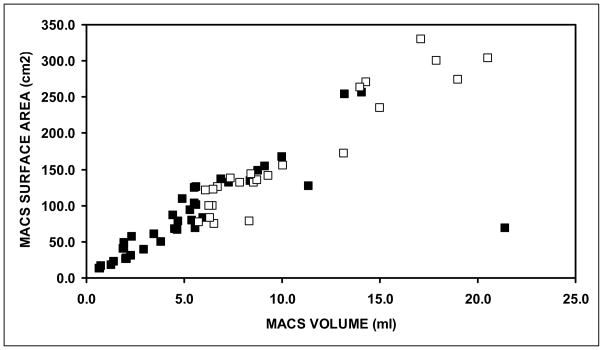

Figure 4 shows the left and right MACS surface areas as a function of their respective MACS volumes. The data for the left ear of Subject 13 again represented an outlier (21.4 ml, 69.1 cm2), and excluding that data point, the MACS surface area versus volume relationship for both ears was linear. For the left and right ears, 89% and 96% of the variance in MACS surface area was explained by the regression on MACS volume (See Table). There was no apparent effect of otitis media history on this relationship.

Figure 4.

MACS surface area for the right (squares) and left (circles) ears of all study subjects as a function of the respective MACS volume. Filled symbols indicate ears of persons with a history of otitis media.

DISCUSSION

In this study, MACS volume was estimated from the pneumatized MACS area obtained from Schuller projection x-rays and also from reconstructions based on CT sections. A comparison of the two measures documented a direct linear relationship with a high correlation coefficient (r≈0.77). A similar linear relationship between these measures was previously reported in a study of 26 normal cadaveric temporal bones (r=0.95).9 These results suggest that pneumatized area measured by a relatively simple x-ray procedure can be used to screen ears for MACS volume as was done in the present study.

Numerous past studies showed that ears with smaller MACS volumes are associated with a greater susceptibility to cholesteatoma and otitis media when compared to ears with larger MACS volumes.2–6 The results of the present study documented lesser MACS volumes in ears of persons with a self-reported history of otitis media when compared to those of persons without a history of otitis media, but the between-group differences were not significant at the usually accepted P=.05 level. This discrepancy between the results of the current and past studies most likely represents the low power for the statistical comparison in the current study given the small number of subjects with a positive disease history as well as the use of group classifications based on historical information obtained from adults who may or may not have knowledge of their disease history and laterality in infancy and childhood.

Reconstructions of the MACS surface area and volume for the left ear of Subject 13 who did not have a self-reported history of otitis media, other middle ear disease or MACS surgery did not fit the relationships noted for all other MACSs included in the study. Visual examination of the CT scans for that ear showed an abnormally high distribution of large air-cells throughout the MACS. In comparison to the other MACSs studied, this geometry was atypical and, while no explanation presents itself to explain this abnormality, the data for that MACS was considered to be an outlier and eliminated from the various correlation coefficients reported in the results section (though that data point was included in all graphs and the regression analyses reported in the Table were done with and without that outlier for completeness).

For both MACS pneumatized area and MACS volume, the measures for the right and left ears of the subjects were highly correlated (r=0.90 and 0.87, respectively). Consequently, the right and left MACS cannot be treated as independent observations and, therefore, the data for the two ears were analyzed separately in this study. This bilateral symmetry suggests that the growth of MACS volume during development is highly heritable as suggested previously,10 but that inflammatory middle ear diseases can stunt the genetically programmed growth of the MACS as shown by others in animal models11 and in humans.6, 12

One previous study of 24 ears of 15 adult subjects with “normal” MACS volumes documented a linear relationship between MACS surface area and volume with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.95.7 The data for the present study are consistent with that result (Figure 4), and as shown in Figure 5, the combined data for the current and previous study confirm a linear relationship between MACS surface area and volume over the full range of MACS volumes included in the two studies (SA=16.1V+2.8, r=0.96, P<.01). The average surface area/volume ratio of the combined data set is 16.7±3.7 cm2/ml as compared to 16.7±3.7 and 17.4±4.8 cm2/ml for the right and left ears of the present study and 15.9±2.6 cm2/ml for the ears in the earlier study. Consequently, we reject our hypothesis that the slope of the function relating MACS surface area to volume is different for smaller versus larger MACS volumes.

Figure 5.

MACS surface area for all ears in the current study (filled squares) and for those in an earlier study by Park and colleagues (open squares) as a function of MACS volume.

The equations for both diffusion-limited and perfusion-limited exchange (assuming that surface area is a function of blood perfusion) directly relate surface area to the exchange rate of a gas across an inert barrier (such as the MACS mucosa).8. Gas exchange across the MACS mucosa has been documented in past studies.13–16 One hypothesis to explain the indirect relationship between MACS volume and otitis media susceptibly2–6 is that the MACS functions as a middle ear gas reserve, and thus, slows the rate of middle ear pressure decrease between Eustachian tube openings.1 A simple mechanism to explain that function is that MACS surface area which is directly related to the gas exchange rate is less for larger MACS volumes. This relationship was not supported by the results of the present study. This suggests that if the MACS functions as a gas reserve, either blood perfusion/surface area is much less in larger MACS or that other mechanisms are in operation.

Indeed an alternative mechanism was advanced recently based on the results of a study that presented evidence showing that gas exchange from blood to middle ear is greater for “healthy” middle ears when compared to those with otitis media or other middle ear diseases.17 The investigators suggested that this is a consequence of the presumably larger MACS volumes in the former group given the reported inverse relationship between larger MACS volume and a greater frequency of otitis media.2–6 One interpretation of these data is that the MACS, and not the Eustachian tube, is the primary gas source for the middle ear.17 If valid, larger MACS volumes would enhance this function and protect the middle ear from the development of significant underpressures. These and other mechanisms of MACS function should be explored more fully in future studies,

SUMMARY

Past studies show that smaller MACS volumes predispose to middle ear diseases.2–6

MACS surface area is directly related to the rate of gas exchange across the MACS mucosa.8

The MACS has been hypothesized to function as a gas reserve for the middle ear and one possible mechanism underlying that function is that the MACS surface area decreases with increasing MACS volume.1

MACS geometry characterized by its surface area-volume relationship has been measured previously in only one study of adults with “normal” MACS volume.7

The present study was performed to characterize MACS geometry over a wide range of volumes.

The results showed that MACS surface was directly related to MACS volume.

This result is inconsistent with the suggested mechanism for the MACS functioning as a gas reserve if the blood perfusion/surface area of the MACS is constant over all MACS volumes.

Alternative mechanisms such as the MACS functioning as a gas source for the middle ear should be evaluated in future experiments.17

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (P50 DC007667). The investigators thank the personnel of the Radiology Department at the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh for their assistance in performing the x-ray and CT procedures and Ms. Julianne Banks for her assistance with subject recruitment and scheduling.

References

- 1.Doyle WJ. The mastoid as a functional rate-limiter of middle ear pressure change. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;71:393–402. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sade J, Fuchs C. A comparison of mastoid pneumatization in adults and children with cholesteatoma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1994;251:191–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00628421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sade J, Fuchs C. Secretory otitis media in adults: I. The role of mastoid pneumatizationas a risk factor. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1996;105:643–7. doi: 10.1177/000348949610500810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sade J, Fuchs C. Secretory otitis media in adults: II. The role of mastoid pneumatization as a prognostic factor. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1997;106:37–40. doi: 10.1177/000348949710600107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lesinskas E. Factors affecting the results of nonsurgical treatment of secretory otitis media in adults. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2003;30:7–14. doi: 10.1016/s0385-8146(02)00100-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valtonen HJ, Dietz A, Qvarnberg YH, Nuutinen J. Development of mastoid air cell system in children treated with ventilation tubes for early-onset otitis media: a prospective radiographic 5-year follow-up study. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:268–73. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000154731.08410.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park MS, Yoo SH, Lee DH. Measurement of surface area in human mastoid air cell system. J Laryngol Otol. 2000;114:93–6. doi: 10.1258/0022215001904969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ranade A, Lambertsen CJ, Noordergraaf A. Inert gas exchange in the middle ear. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1980;371:1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colhoun EN, O'Neill G, Francis KR, Hayward C. A comparison between area and volume measurements of the mastoid air spaces in normal temporal bones. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1988;13:59–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1988.tb00282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diamant M. Mastoid Pneumatization and Normal Curve Distribution. Acta Otolaryngol. 1965;60:167–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aoki K, Esaki S, Honda Y, Tos M. Effect of middle ear infection on pneumatization and growth of the mastoid process. An experimental study in pigs. Acta Otolaryngol. 1990;110:399–409. doi: 10.3109/00016489009107461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tos M, Stangerup SE. Mastoid pneumatization in secretory otitis. Further support for the environmental theory. Acta Otolaryngol. 1984;98:110–8. doi: 10.3109/00016488409107542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takahashi H, Honjo I, Naito Y, Miura M, Tanabe M, Hasebe S, et al. Gas exchange function through the mastoid mucosa in ears after surgery. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:1117–21. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199708000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takahashi H, Sugimaru T, Honjo I, Naito Y, Fujita A, Iwahashi S, et al. Assessment of the gas exchange function of the middle ear using nitrous oxide. A preliminary study. Acta Otolaryngol. 1994;114:643–6. doi: 10.3109/00016489409126119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanabe M, Takahashi H, Honjo I, Hasebe S. Gas exchange function of the middle ear in patients with otitis media with effusion. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1997;254:453–5. doi: 10.1007/BF02439979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ikarashi F, Tsuchiya A. Middle ear gas exchange via the mucosa: estimation by hyperventilation. Acta Otolaryngol. 2008;128:9–12. doi: 10.1080/00016480701200269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen D, Raveh D, Peleg U, Nazarian Y, Perez R. Ventilation and clearance of the middle ear. J Laryngol Otol. 2009;123:1314–20. doi: 10.1017/S0022215109991034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]