Abstract

The development of disseminated (miliary) abdominal tuberculosis (TB) in patients following operations which affect their immunity, such as laparoscopic gastric bypass, is rare. The authors report the case of middle aged woman, who a few months after undergoing laparoscopic gastric bypass surgery for morbid obesity (body mass index 49), presented with generalised fatigability and abnormal liver function. A CT scan of the abdomen was suggestive of miliary TB. The patient developed acute abdomen pain. Intraoperative findings included perforated stomal ulcers at the gastrojejunostomy, diffuse micronodular involvement of the liver and spleen and thickened omentum. The perforation was closed and liver and omental biopsies were taken. Histology results from the liver and omentum revealed necrotising granulomatous inflammation suggestive of TB. Abdominal TB is a relatively rare manifestation of extrapulmonary TB. However, this diagnosis should be considered in patients immunocompromised due to immunosuppressive medication or operations affecting their nutrition. Early diagnosis and effective treatment of abdominal TB may decrease morbidity and mortality in such patients.

Background

Tuberculosis (TB) is a growing problem worldwide. Consequently, it is vital to recognise the more unusual presentations of this disease. Intra-abdominal TB has a high mortality but is difficult to diagnose, sometimes requiring surgical interventions for diagnosis and treatment. Massive abdominal TB is particularly rare and most cases are secondary infections associated with pulmonary TB. According to the WHO, one-third of the world’s population is at risk from TB, and in the 1990s more than 30 million people died of this disease, particularly in Asia and Africa.1

Case presentation

A middle-age female, who had been treated with a laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) for morbidly obesity (body mass index 49) a few months previously, presented to the clinic for follow-up complaining of generalised fatigability, jaundice, abdominal distension and weight loss of 30 kg over the past 2 months. The patient reported no nausea or vomiting, no history of changed bowel habits, no fever or night sweating, and no clear history of documented TB. She was discharged on vitamin supplements. Clinical examination revealed that the patient was jaundiced and pale, and the abdomen was centrally distended with bulging flanks, and was soft and lax, with positive signs of ascites.

Investigations

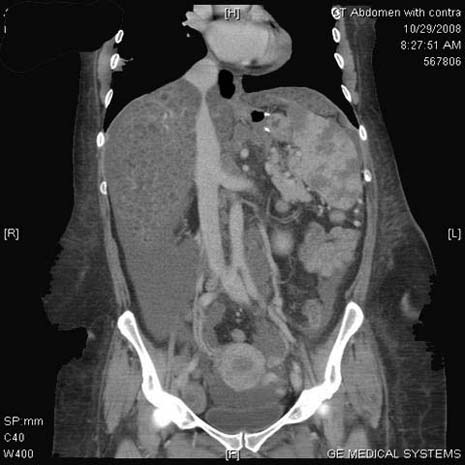

On laboratory investigations, haemoglobin levels were 6.9 g/dl, total leucocyte count was 12.8, platelet count was 205 and erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 123 mm. A liver function evaluation revealed a total serum bilirubin level of 122 mmol/l, aspartate amino transferase of 1604 IU/l, alanine aminotransferase of 667 IU/l, alkaline phosphatase of 17 IU/l, INR of 2.1 and fibrinogen levels of 1.4. The levels of tumour markers were: CEA 2.4, AFP 0.9 and CA 19-9255. Abdominal CT showed enlarged and calcified subcarinal and left hilar lymph nodes, multiple scattered 5 mm micronodules in the lower lobes of both lungs in a subpleural distribution with ‘feeding vessel signs’, an enlarged liver and spleen showing infiltration by innumerable hypoechoic micronodules scattered among the lobes of both these organs, multiple enlarged para-aortic, peri-pancreatic and porta hepatis lymphadenopathies, and a large amount of ascites (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Abdominal CT scan.

Differential diagnosis

These findings were suggestive of a disseminated infection, most likely TB (either secondary to malnutrition or exposure to TB at the time of original surgery), widespread metastasis and lymphoma.

Treatment

The patient was admitted as a case of post-RYGB malnutrition with liver impairment for investigation and management, and was administered prophylactic antibiotics. Hepatology and infection teams were consulted and recommended a liver biopsy before starting anti-TB therapy. The patient was booked for an ultrasound guided liver biopsy, but developed acute abdomen pain during the night. After resuscitation, the patient was taken to the operating room for an exploratory laparotomy. Intraoperative findings included massive bile stained ascites, a perforated stomal ulcer at the gastrojejunostomy, diffuse granular involvement of the liver and spleen, an enlarged spleen and a thickened, fibrotic, diffusely granular omentum. Resection of the ulcer and closure of the perforation was performed, along with a wedge liver biopsy and an omental biopsy, and a sample of ascitic fluid was sent for laboratory analysis. The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) but unfortunately did not respond to the supportive care and developed multiorgan failure. The patient died 2 days later.

Outcome and follow-up

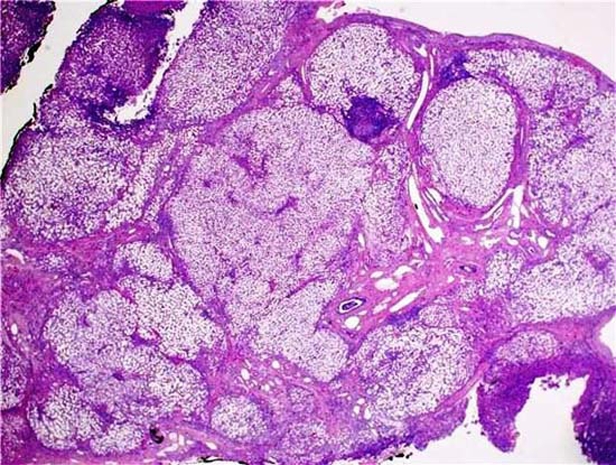

The histopathology results were as follows. The wedge liver biopsy showed features of cirrhosis, extensive steatosis (>95% of parenchyma) and necrotising granulomatous inflammation highly suggestive of TB. The omental and mesenteric lymph node biopsy also showed necrotising granulomatous inflammation. Microscopy and microbiology of the ascitic fluid showed few white blood cells and no bacteria (figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Liver histopathology.

Figure 3.

Omentum histopathology.

Discussion

Abdominal TB is defined as an infection in the gastrointestinal tract, the peritoneum or the intra-abdominal solid organs by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It constitutes about 12% of extra-pulmonary cases of TB and 1–3% of all cases of TB.2 Along with increased use of immunosuppressive therapies, the incidence of abdominal TB has been rising in low and middle income societies.3 The TB infection in our patient was caused by one of two scenarios: dormant TB may have been reactivated as a result of the patient losing weight quickly with consequent changes in the pattern of nutrition and the patient’s immune system or the patient may have acquired the infection during the first operation. Indeed, we consider that bariatric surgery may lead to such infection (even if not mentioned previously in the medical literature) and so the patient should be examined carefully and an accurate medical history taken.

The diagnosis of abdominal TB can be difficult due to the non-specific presentation of symptoms and signs. In addition, abdominal TB can mimic many diseases and conditions such as malignancy, bacterial infectious diseases and inflammatory diseases.4 Undiagnosed and untreated abdominal TB can result in a mortality of 50–60%.5 Sepsis and liver cirrhosis may be strongly associated with therapeutic failure in cases of abdominal TB.

TB may reach the abdomen via three main pathways.6 The mucosal layer of the gastrointestinal tract may be infected by ingestion of unpasteurised milk infected with M tuberculosis or Mycobacterium bovis. Another mechanism of ingestion is via infected sputum in patients with active pulmonary TB. At a later stage, the deep layers of the bowel wall and the adjacent regional lymph nodes and peritoneum may be involved. Rarely, infection may spread to the liver and spleen from para-aortic or portal nodes via the portal vein or hepatic artery,7 with subsequent formation of macronodular tuberculous foci within the liver and spleen. The second main pathway is haematogenous spread from a tuberculous focus elsewhere in the body. The peritoneum, lymph nodes and solid abdominal organs and kidneys are usually involved in this pathway. Haematogenous spread may occur years before the onset of progressive abdominal TB, as the foci of a latent infection may lie dormant before reactivation occurs, as was the case in our patient. The third pathway includes direct spread to the peritoneum from infected adjacent foci, including the fallopian tubes or adenxa, or a psoas abscess, secondary to tuberculous spondylitis.

Three diagnostic stages have been evaluated in the diagnosis of abdominal TB.8 The first two stages, clinical evaluation of the patient and radiological examination, provide indirect evidence of the disease. The third stage includes invasive techniques to obtain direct evidence. However, the diagnosis of TB has its own difficulties as such evidence is generally relatively direct in practice. The clinical presentation of abdominal TB is usually non-specific and, therefore, often results in diagnostic delay and the development of complications. The most common clinical symptoms and signs in patients with abdominal TB are abdominal pain, abdominal distension, ascites, fever, jaundice and weight loss. Definitive diagnosis relies on the demonstration of either caseating granulomas, the presence of AFB on Ziehl–Neelson staining, or the presence of M tuberculosis DNA by PCR in specimens obtained through ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration cytology, CT guidance or surgery (laparoscopic, open). CT scan features suggestive of abdominal TB include bowel wall thickening, mesentric lymphadenopathy, ascites and the presence of an abscess. Although these findings are non-specific, the diagnosis of abdominal TB should be considered in immunocompromised patients and those with previous pulmonary TB. Hepatosplenic TB is seen in up to 50–80% of disseminated TB cases,9 as in our patient. This type of TB may originate either from the haematogenous spread of pulmonary or military TB or through the portal venous system from gastrointestinal lesions. There are two main types of hepatosplenic TB,10 the micronodular and the macronodular forms. The micronodular form is most common and manifests usually only as moderate hepatosplenomegaly which appears on CT as tiny low-density foci throughout the liver and spleen. In our patient the micronodular form spread in both the liver and spleen.

The recommended treatment for abdominal TB is conventional anti-TB therapy for a minimum of 6 months. Surgical intervention may be required to establish a diagnosis if medical treatment fails or to treat complications of abdominal TB. Laparoscopy has been advocated as the ideal method for achieving a definitive diagnosis in patients with suspected abdominal TB.

Learning points.

-

▶

Abdominal tuberculosis (TB) is a relatively rare manifestation of extrapulmonary TB.

-

▶

Abdominal TB as a specific complication of malabsorptive surgery seems unlikely in view of the absence of previously documented cases.

-

▶

The diagnosis of abdominal TB should be considered in patients immunocompromised either because of immunosuppressive medication or operations that affect their nutrition and immunity, who have non-specific symptoms of abdominal pain, fever, ascites, weight loss and jaundice.

-

▶

Early diagnosis and effective treatment of abdominal TB may decrease the morbidity and mortality associated with this disease.

Footnotes

Competing interests None.

Patient consent Not obtained.

References

- 1.WHO Tuberculosis control and research strategies for the 1990s. memorandum from a WHO-meeting. Bull. World health organ 1992;70:17–21 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sheer TA, Coyle WJ. Gastrointestinal tuberculosis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2003;5:273–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes PF, Barrows SA. Tuberculosis in the 1990s. Ann Intern Med 1993;119:400–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jadvar H, Mindelzun RE, Olcott EW, et al. Still the great mimicker: abdominal tuberculosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1997;168:1455–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chow KM, Chow VC, Hung LC, et al. Tuberculous peritonitis-associated mortality is high among patients waiting for the results of mycobacterial cultures of ascitic fluid samples. Clin Infect Dis 2002;35:409–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hopewell PC. A clinical view of tuberculosis. Radiol Clin North Am 1995;33:641–53 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akhan O, Pringot J. Imaging of abdominal tuberculosis. Eur Radiol 2002;12:312–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uygur-Bayramicli O, Dabak G, Dabak R. A clinical dilemma: abdominal tuberculosis. World J Gastroenterol 2003;9:1098–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alvarez SZ, Carpio R. Hepatobiliary tuberculosis. Dig Dis Sci 1983;28:193–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drevelengas A. The spleen in infectious disorder. In: De Schepper AM, Vanhoenacker F, eds. Medical Imaging of the Spleen. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; New York: Heidelberg; 2000:67–80 [Google Scholar]