Abstract

Proteins and small peptides (growth factors and hormones) are key molecules in maintaining cellular homeostasis. To that end, Notch signaling pathway proteins are known to play critical roles in maintaining the balance between cell proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis, and thus it has been suggested that Notch may be responsible for the development and progression of human malignancies. Therefore, the Notch signaling pathway proteins may present novel therapeutic targets, which could have promising therapeutic impact on eradicating human malignancies. This review describes the role of Notch signaling pathway proteins in cancer and how its deregulation is involved in tumor development and progression leading to metastasis and the ultimate demise of patients diagnosed with cancer. Further, we summarize the role of several Notch inhibitors especially “natural agents” that could represent novel therapeutic strategies targeting Notch signaling toward better treatment outcome of patients diagnosed with cancer.

Keywords: Notch, cancer, signal pathway, review, natural agents, cancer therapy, γ-secretase inhibitors, oncogene

BACKGROUND

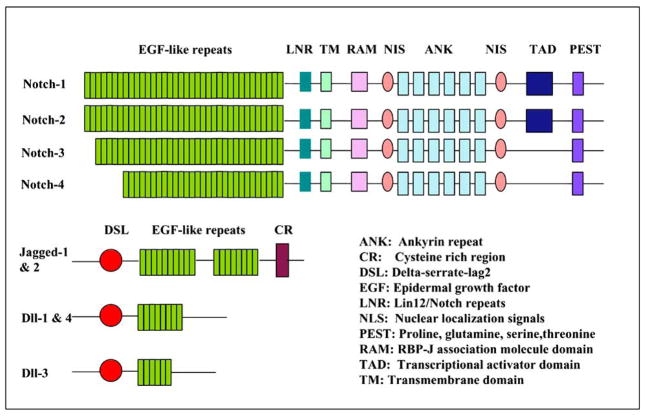

Since there are more than 30,000 proteins and small peptides that are key regulators in maintaining cellular homeostasis, it is difficult to appreciate the value of a specific and single protein especially because protein-protein interactions and the role of multiple proteins are important in biological systems. However, our focus for this review article is centered around on one such important class of proteins namely Notch proteins. The Notch signaling pathway is a conserved ligand–receptor signaling pathway that plays critical mechanistic roles in cell proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis [1]. To date, there are four Notch receptors identified in mammals such as Notch-1, Notch-2, Notch-3 and Notch-4. The mammalian canonical ligands are designated as either Delta-like (Dll-1, Dll-3 and Dll-4) or Serrate-like due to similar structural homology as to the two drosophila ligands, Delta and Serrate Fig. (1). There are two distinct Serrate-like ligands, known as Jagged-1 and Jagged-2 [2]. All four Notch receptors are very similar although they have subtle differences in their extracellular and cytoplasmic domains. The extracellular domains of the Notch proteins possesses multiple repeats which are related to epidermal growth factor (EGF) and are thought to be participated in ligand binding. Specifically, the Notch-1 and Notch-2 proteins contain 36 arranged repeats of EGF-like domain, while Notch-3 and Notch-4 have 34 and 29, respectively [3]. It is known that the order of the EGF-like repeats has been conserved among the Notch proteins. However, the function of spatial arrangement of the repeats is largely unclear. The amino-terminal EGF-like repeats are followed by cysteine-rich region termed the LNR (LIN-12/Notch-related region) that prevent signaling when ligand is absent. The cytoplasmic region of Notch conveys the signal to the nucleus; it contains a Recombination Signal-Binding Protein 1 for J-kappa (RBP-J)-association molecule (RAM) domain, ankyrin (ANK) repeats, nuclear localization signals (NLS), a transactivation domain (TAD) and a region rich in proline, glutamine, serine and threonine residues (PEST) sequence. It is known that PEST sequence is involved in Notch protein turnover while the ANK repeats are necessary and sufficient for Notch activity. Notch ligands have multiple EGF-like repeats in their extracellular domain and a cysteine-rich region (CR) in Serrate which are absent in Delta. Jagged-1 and Jagged-2 have almost twice the number of EGF-like repeats [4].

Fig. 1.

Structure of Notch receptors (1–4) and ligands (Jagged-1, 2, Dll-1, 3, 4). Both receptors and ligands contain multiple conserved domains. Notch is a single-pass transmembrane receptor. The extracellular domain contains EGF-like repeats and a cysteine-rich region. The intracellular domain contains the RAM domain, NLS, ANK, TAD and PEST domain. Notch ligands have multiple EGF-like repeats in their extracellular domain and a CR in Jagged which are absent in Delta.

Notch signaling is initiated when Notch ligand binds to an adjacent Notch receptor between two neighboring cells. Upon activation, Notch is cleaved, releasing the Notch intracellular domain (NICD) through a cascade of proteolytic cleavages by the metalloprotease, tumor necrosis factor-α-converting enzyme (TACE) and γ-secretase [5]. The first cleavage is mediated by TACE, which cleaves the receptor in the extracellular domain. The released Notch extracellular truncation (NEXT) is then trans-endocytosed by the ligand-expressing cell [5]. The second cleavage can occur at the cell surface and within the endosomal trafficking pathway. The second cleavage caused by the γ-secretase activity of a multi-protein complex consisting of presenilin, nicastrin, etc. releases the Notch intracellular domain (NICD) which is then ready to be translocated into the nucleus for transcriptional activation of Notch target genes. Therefore, inhibiting γ-secretase function is known to prevent the cleavage of the Notch receptor and blocks Notch signal transduction. In the absence of NICD, transcription of Notch target genes is maintained in inactive state through a repressor complex mediated by the CSL (CBF1, Suppressor of Hairless, Lag-1). When NICD enters the nucleus, co-repressors associated with CSL are displaced and a transcriptionally active complex consisting of CSL, NICD, Mastermind, and other co- activators is formed, which converts CSL from a transcriptional repressor into an activator, leading to activation of Notch target genes [1, 5, 6]Fig. (2). The complexity of the various repressor and activator nuclear complexes in Notch signaling is not yet fully known.

Fig. 2.

Schematic of Notch signaling. Notch signaling is initiated when Notch ligand binds to an adjacent Notch receptor between two neighboring cells. Upon activation, Notch is cleaved, releasing the Notch intracellular domain (NICD) through a cascade of proteolytic cleavages by the metalloprotease, tumor necrosis factor-α-converting enzyme (TACE) and γ-secretase. NICD is translocated into the nucleus for transcriptional activation of Notch target genes. In the absence of NICD, transcription of Notch target genes is maintained in inactive state through a repressor complex mediated by the CSL (CBF1, Suppressor of Hairless, Lag-1). When NICD enters the nucleus, co-repressors associated with CSL are displaced and a transcriptionally active complex consisting of CSL, NICD, Mastermind, and other co-activators is formed, which converts CSL from a transcriptional repressor into an activator, leading to activation of Notch target genes.

A few Notch target genes have been identified, some of which are dependent on Notch signaling in multiple tissues, while others are tissue specific. Notch target genes include the Hairy enhance of split-1 (Hes-1), nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB), cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9), extracellular-regulated kinase (ERK), Akt, cyclin D1, c-myc, p21 cip1, p27 kip1, p53, etc. [1, 2, 6–8]. These results suggest that Notch signaling may play critical roles in human cancers as discussed below.

NOTCH SIGNALING IN CANCER

It is well known that Notch signaling plays important roles in maintaining the balance involved in cell proliferation, survival, apoptosis, and differentiation which affects the development and function of many organs [1]. It has been shown that the function of Notch signaling in tumorigenesis can be either oncogenic or anti-proliferative, and the function is context dependent [1]. Notch signaling is anti-proliferative rather than oncogenic in a limited number of tumor types such as hepatocellular carcinoma, skin cancer, and small cell lung cancer [7, 9]. However, most of the studies have shown an opposite function, i.e., oncogenic function of Notch in many human carcinomas. It has been reported that the Notch signaling network is frequently deregulated in human malignancies with up-regulated expression of Notch receptors and their ligands were found in cervical, lung, colon, head and neck, renal carcinoma, prostate, acute myeloid, Hodgkin and large-cell lymphomas and pancreatic cancer (Table 1). Here, we attempted to summarize the functional role of Notch in different human malignancies; however we sincerely apologize to those authors whose work has not been cited in this succinct review article because of space limitation.

Table 1.

Expression of Notch Pathway Elements in Different Human Cancers

| Cancer Type | Notch Signaling | Key Gene Targets | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pancreatic cancer | Notch-1,2, Jagged-1,2 | Bcl-2, VEGF, MMP-9, | [11–17] |

| Prostate cancer | Notch-1, 2, Jagged-1, 2 | Hes-1, Hey-1, MMP-9, uPA, AR | [22–28] |

| Breast cancer | Notch-1,3,4, Jagged-1, Dll-4 | mTOR, p53, NF-κB, surviving, ER, Slug, E- cadherin, β-catenin | [33–40] |

| Lung cancer | Notch-1, 2,3 Jagged-1, 2 |

pERK, Hes-1, MAPK | [43–50] |

| Colorectal cancer | Notch-1, Jagged-1, 2 | Hes-1, KLF-4, | [51–56] |

| Renal cancer | Notch-1, Dll-4, Jagged-1 | P21, P27 | [57, 58] |

| Hepatocellular cancer | Notch-1, 2, 3,4, Dll-4, Jagged-1, | Cyclin A1, RB, Cyclin D1, Cyclin E, CDK2, p53, Bcl-2 | [60–69] |

| T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia | Notch-1, 3 | Hes-1, RB, Cyclin D1, Akt, P21, CDK2, P53 | [70–74] |

| Glioblastoma | Notch-1, 2, Dll-1, Jagged-1 | Hey-1, Hes-1, RBP-J, Nestin | [75–80] |

| Cervical cancer | Notch-1, Jagged-1 | Hes-1, NF-κB, PI3K, pAKT, Cyclin D1, C-myc | [82–87] |

| Gastric cancer | Notch-1, Jagged-1 | COX-2 | [93, 94] |

PANCREATIC CANCER

Pancreatic cancer is one of the most common cancers and is the fourth leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States [10]. Approximately, 42,470 people are expected to be diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and 35,240 people are expected to die from this disease in the United States in 2009. Presently, for all stages combined, the 1-year survival rate is only 20%, and the 5-year survival rate is less than 5% [10]. Pancreatic cancer has been shown to over-express the Notch signaling pathway related molecules. The high level expression of Notch receptors (Notch-1 and Notch-2), Notch ligands (Jagged-1 and Jagged-2) and Notch target genes (Hes-1, Hes-4, Hey-1) have been observed in pancreatic cancer [11–17]. Notch activity is required for TGF-α-induced acinar-to-ductal transition. Prevention of Notch activation by γ-secretase inhibitors (GSI) prevents acinor-to-ductal metaplasia in TGF-α-treated cells [12]. We also found that down-regulation of Notch-1 using specific siRNA or treatment with GSI was correlated with decreased proliferative rates, increased apoptosis, reduced migration, and decreased invasive properties of pancreatic cancer cells [18, 19]. Moreover, we found that Notch signaling pathway is highly up-regulated in Gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic cancer cells, which show the acquisition of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) phenotype [20]. Recently, it was shown that both Notch activation and activated K-Ras signaling act cooperatively to initiate pancreatic carcinogenesis [13, 14]. Very recently, Notch signaling pathway was reported to be involved in microRNA-34 regulation in pancreatic cancer stem cell self-renewal. MicroRNA-34 regulates pancreatic cancer stem cell self-renewal via the direct modulation of downstream target Notch [21]. Therefore, inhibiting Notch signaling could potentially represent an attractive new therapeutic strategy by the killing of cancer stem cells, and in turn improve treatment outcome of patients diagnosed with pancreatic cancer.

PROSTATE CANCER

Prostate cancer has become a significant health problem because it is one of the most frequently diagnosed tumors in men, and the second leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States [10]. The progression of prostate cancer involves several signaling pathways including Notch signaling. Emerging evidence suggest that Notch signaling pathways play important roles in prostate development and progression, especially because Notch signaling pathway was found to be over-expressed in prostate cancer cell lines [22–25]. In addition, Notch-1 over-expression has been reported in prostate cancer metastases. Specifically, bone metastases of prostate cancer patients expressed Notch-1 protein in osteoblastic prostate cancer metastatic cells [26]. Moreover, Jagged-1 is highly expressed in metastatic prostate cancer compared to localized prostate cancer or benign prostatic tissues. Furthermore, high Jagged-1 expression in a subset of clinically localized tumors was significantly associated with recurrence, suggesting that Jagged-1 may be an useful marker in distinguishing indolent vs. aggressive prostate carcinomas [27]. Recently, Hafeez et al. reported that silencing of Notch-1 inhibited invasion of prostate cancer cells by inhibiting the expression of MMP-9 and uPA [23]. We have reported that down-regulation of Notch-1 and Jagged-1 inhibited the prostate cancer cell growth [28]. We also found that down-regulation of Notch-1 and Jagged-1 could be an effective approach for inhibiting cell growth, migration and invasion, and inducing apoptotic cell death, which was associated with inactivation of Akt, mTOR (mammalian Target of Rapamycin) and NF-κB, and the expression and activity of NF-κB target genes such as urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) and MMP-9 (unpublished data). Studies have shown that a potential relationship between p53 status and Notch-1 expression exists within prostate cancer cells. Restoration of p53 function in prostate cancer cell lines that are deficient in p53 function up-regulated the expression of Notch-1, while knockdown of p53 expression in prostate cancer cells that express wild-type p53 resulted in reduced expression of Notch-1 [29]; however the mechanism of these important biological phenomenon is still unknown.

Androgen receptor (AR) was also found to be involved in Notch pathway in prostate cancer cells because the expression of Notch-1 and Jagged-1 were found to be regulated by AR [30]. Moreover, Notch target gene Hey-1 could function as a co-repressor for the activation function 1 in the AR, suggesting that it has a negative feedback loop between AR and Notch pathways [31]. Very interestingly, Shou et al. reported that over-expression of Notch-1 inhibited the prostate cancer cell growth, suggesting that the role of Notch signaling in prostate tumorigenesis needs to be further investigated [22].

BREAST CANCER

Breast cancer remains the second most common and lethal malignancy in women worldwide, suggesting that early diagnosis and prevention of this disease is urgently needed. Currently, breast cancer is treated with surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy or combined modalities with remarkable success. Although these treatment modalities are successful, either a significant number of patients do not respond to therapy, or the tumor may recur during therapy and develop metastasis, for which there is limited curative therapeutic options [10]. Breast cancer like many other tumors has been shown to over-express the Notch signaling pathway [32, 33]. Moreover, high-level expression of Notch-1 and its ligand Jagged-1 was found to be associated with poor prognosis in breast cancer. Specifically, patients with tumors expressing high levels of Jagged-1 or Notch-1 had a significantly poorer overall survival compared to patients expressing low levels of these genes in their tumor specimens. Furthermore, a synergistic effect of high-level Jagged-1 and high-level Notch-1 co-expression on overall survival was observed in breast cancer [34]. Notch has been found to cross-talk with other pathways in breast cancer. For example, NICD inhibited tumor protein p53 through mTOR using the PI3K/Akt pathway especially because rapamycin, an inhibitor of mTOR, treatment abrogated NICD inhibition of tumor protein p53 and reversed the chemo-resistance of breast cancer [35]. Notch pathway has been shown to regulate survivin, estrogen receptor, Slug, E-cadherin, β-catenin and other important signaling proteins in breast cancer [36–38]. Very interestingly, Notch-2 signaling, unlike Notch-1, Notch-3, and Notch-4, induced apoptosis and inhibited breast cancer cell growth in vitro and in vivo [39, 40], suggesting that novel Notch inhibitors would be useful for the treatment of breast cancer.

Recently, Notch signaling was shown to be causally associated in promoting the formation of cancer stem cells (CSC) in human breast cancer. Phillips et al. reported that cancer stem cells can be identified by phenotypic markers and their fate is controlled by the Notch pathway in breast cancer [41]. Recombinant human erythropoietin receptor increased the numbers of stem cells and the self-renewing capacity in a Notch-dependent fashion by the induction of the Jagged-1. Inhibitors of the Notch pathway blocked this effect, suggesting the mechanistic role of Notch signaling in the maintenance of the breast CSC phenotype [41]. Farnie et al. also provided evidence in support of breast CSCs and their studies have consistently shown that stem-like cells and breast cancer initiating populations can be enriched using the cell surface markers CD44+/CD24− that showed up-regulated genes including Notch [42]. Therefore, targeting Notch signaling may be a promising approach for the treatment of breast cancer by eliminating CSCs.

LUNG CANCER

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death which kills more than 3,000 people every day [10]. Lung cancer can be categorized into two broad major histopathologic groups: non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and small cell lung cancer (SCLC). Small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC) represents 15–20% of all lung cancer whereas approximately 80–85% of human lung cancers are NSCLC [10]. NSCLC are comprised of adenocarcinomas, squamous cell, and large cell carcinomas. Despite the recent advances in surgical methods, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy, the disease is rarely curable, and thus the overall 5-year survival rate is only 15% [10]. Notch signaling pathway was also found to be involved in the progression of lung cancer [43]. Very interestingly, Notch expression is known to function as both oncogenic or tumor suppressive depending on tumor cell type in lung cancer. SCLC appears to be growth inhibited by over-expression of activated Notch-1 and Notch-2 whereas Notch has a growth promoting function in NSCLC [43, 44]. Activated Notch-1 and Notch-2 caused G1 arrest accompanied by up-regulation of p21 cip1 in SCLC cells. Activated Notch-1 also led to a marked increase in pERK1 and pERK2 in SCLC cells [44]. In addition, NSCLC has high expression of Hes-1, whereas SCLC expressed low or undetectable level of Hes-1 [45]. Oxygen concentration could affect the expression of Notch because oxygen concentrations are important in normal lung physiology and lung tumors are hypoxic in most cases. Indeed, hypoxia dramatically elevates Notch signaling in NSCLC cell lines and concomitantly sensitizes them to be inhibited via GSI or Notch siRNA [46]. In NSCLC cell lines, Notch-3 gene was found to have high expression because Notch-3 gene on chromosome 19 is also involved in balanced translocations with multiple other chromosomes [47, 48]. Recently, it was reported that dominant-negative Notch-3 or GSI MRK-003 inhibited Notch-3 signaling, reduced tumor cell proliferation and induced apoptosis through mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) pathway in lung cancer [49, 50]. Very recently, Notch ligands Jagged-1 and Jagged-2 were found to have distinct biological roles including the role for Jagged-2 in regulating the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in NSCLC cells. These reports clearly suggest a provocative role of Notch in human lung cancer although further in-depth studies are needed in order to clarify the biological significance and mechanisms on how Notch could regulate the progression of lung cancer.

COLORECTAL CANCER

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of cancer death after lung cancer in the United States. Nearly 50,000 Americans will die from it this year [10]. CRC is known to contain numerous genetic and physiological alterations affecting cell survival and proliferation. One of the most common alterations is Notch signaling. Notch signaling can control intestinal homeostatic self-renewal which are remarkably symmetrical to and those cells that underlie colorectal cancer [51]. For example, Notch-mediated Hes-1 expression regulates a binary decision between adsorptive and secretory cell fates whereas other basic helix-loop-helix proteins may refine these fate decisions [51]. It has been reported that up-regulation of the Notch-1, Jagged-1, and Jagged-2 was found in human intestinal adenomas, suggesting that elevated Notch signaling may contribute to the initiation of colorectal cancer [52–54]. Inducing the formation of intestinal adenomas, particularly in the colon, needs activated Notch and Wnt signal pathway [54]. Moreover, the expression of Notch-1 increased from normal colon mucosa to stage IV metastatic cancers with levels being highest in liver metastases compared to normal colonic mucosa or liver parenchyma [55]. Notch signaling suppresses Krüppel-like factor 4 (KLF4) expression in intestinal tumors and colorectal cancer cells [56]. Furthermore, chemotherapy such as oxaliplatin, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) induces NICD and Hes-1 through up-regulation of γ-secretase activity, and thus the inhibition of Notch-1 by GSI or siRNA shown to decrease chemo-resistance in colon cancer [55]. Interestingly, GSI enhanced taxane-induced mitotic arrest and apoptosis of colon cancer cells both in vitro and in vivo [53], suggesting that combining GSI with chemotherapy may represent a novel approach for the treatment of metastatic colon cancer.

RENAL CANCER

Renal cancer (renal cell carcinoma; RCC) is the second most lethal of the urological cancers in the United States. It has been reported that Notch signaling cascade is constitutively active in human clear cell RCC (CCRCC) [57]. Specifically, Notch-1 and Jagged-1 are highly expressed in CC-RCC cell lines and tumor tissues. Down-regulation of Notch-1 inhibited the CCRCC cell growth in vitro and in vivo through up-regulation of p21 cip1 and p27 kip1 [57]. Notch ligand Dll-4 was also up-regulated in CCRCC. Moreover, the expression of Dll-4 in endothelial cells was up-regulated by VEGF and basic fibroblast growth factor synergistically, and by hypoxia through hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha [58]. Interestingly, Sun, et al. has recently reported that the expression levels of Notch-1 and Notch-4 were absent or significantly decreased in renal cell lines and renal carcinoma tissues, and Notch-1 expression was negatively correlated with renal tumor stage [59]; however the biological implications of controversial finding must be resolved, which of course require further in-depth investigations in establishing the role of Notch signaling in RCC.

HEPATOCELLULAR CARCINOMA

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a common malignant neoplasm in the world. Notch signaling pathway has been reported to play critical roles in HCC. The role of Notch signaling, which is known to act as oncogene or tumor suppressor gene depended on cell type in hepatocellular carcinoma has been reported. For example, Notch-1 signaling can significantly inhibit the in vitro and in vivo growth of the HCC cell line SMMC7721, which was in part due to G0/G1 cell cycle arrest. Notch-1 signaling was found to down-regulate the expression of cyclin A1, cyclin D1, cyclin E, CDK2, and phosphorylation of Rb and that Notch-1 signaling also induced apoptosis of SMMC7721 cells through up-regulation of p53 expression, down-regulation of Bcl-2, and activation of the stress-activated protein kinase/JNK pathway in SMMC7721 cells [60]. Recently, studies from this group reported that Notch-1 signaling sensitizes tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)-induced apoptosis in HCC cells by inhibiting Akt/HDM2-mediated p53 degradation and by up-regulating p53-dependent DR5 expression [61].

In contrast, Notch signaling was found to positively regulate cell proliferation in hepatoma HepG2 cell lines and GSI treatment inhibited tumor cell proliferation through the suppression of Notch signaling [62, 63]. Notch-3 depletion inhibited HepG2 cell growth through up-regulation of p53 expression [63]. In transgenic mice developing hepatocarcinoma, the expression of Dll-4 and active Notch-4 was gradually up-regulated within the hepatocarcinoma progression in livers [64]. Notch-1 and Jagged-1 were frequently low expressed in hepatocellular carcinoma tissues and correlated with the high expression of β-catenin. Decreased expression of Notch-1 and Jagged-1 was correlated significantly with Edmondson-Steiner grade in hepatocellular carcinoma patients [65]. However, Gao, et al. reported that Notch-1 and Notch-4 were up-regulated and Notch-2 was down-regulated in HCC tissues compared to adjacent non-tumor liver tissue [66]. Gao, et al. also found that Jagged-1 was highly expressed in 79.2% of HCC tissues compared to adjacent non-tumor liver and its expression was regulated by hepatitis B virus X protein [67]. HCC tissues also displayed abnormal accumulation of Notch-3 and Notch-4 [68]. Recently, it has been reported that Aspartyl-(asparagyl)-beta-hydroxylase may mediate its effects on hepatoma cell motility by increasing Notch protein accumulation and nuclear translocation, perhaps through increased hydroxylation or binding and stabilization of the protein [69]. Taken together, we believe that the role of Notch signaling should be further investigated in HCC.

T-CELL ACUTE LYMPHOBLASTIC LEUKEMIA

T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) is a neoplastic disorder of lymphoblasts. T-ALL is an aggressive disease with a poorer clinical outcome than B-ALL. Notch pathway has been reported in the development of T-ALL. In 1991, the Notch-1 gene has been originally identified as having a role in human leukemogenesis through chromosomal translocation t(7:9) (q34; q34.3) [70]. Forced expression of Notch-1 in mouse bone marrow results in the development of T-cell leukemia. And more importantly, amplified Notch signaling contributes to approximately 50% of human T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. The roles of Notch pathway in T-ALL have recently been reviewed [71–74] and the readers who are interested in learning more on the role of Notch in T-ALL can consult these excellent reviews. These reviews discussed the cross-talk between Notch signaling pathway and other pathways, and how Notch mutations drive T-ALL development.

GLIOBLASTOMA

Glioblastoma is the most common form of malignant brain tumor. Notch signaling has been reported to be involved in glioblastoma. Shin, et al. found that Notch receptors and ligands are expressed in vitro and in human samples of glioblastomas, the highest grade of malignant gliomas [75, 76]. The expression of Notch target gene Hey-1 in glioblastomas was also found to be correlated with tumor-grade and survival [77]. In malignant gliomas as well as in glioblastoma cell lines, Notch-2 protein was found to be strongly expressed. Notch-2 is known to regulate Tenascin-C gene in an RBPJk-dependent manner mediated by an RBPJk binding element present in the Tenascin-C promoter [78]. Interestingly, a significant over-expression of Notch-1 and Hes-1 was found in the brain tumor stem cells, suggesting that Notch pathway was involved in self-renewal of stem cells and their transformation to cancer stem cells [79]. Forced expression of ID-4 (inhibitor of differentiation 4) has been shown to drive malignant transformation by increased expression of Jagged-1 and Notch1 activation mediated by guiding astrocytes into a neural stem-like cell state [80]. Very recently, it was found that miR-34a suppressed brain tumor growth by targeting c-Met and Notch [81] and these reports clearly suggest that Notch could serve as a potential therapeutic target for brain tumors.

CERVICAL CANCER

Cervical cancer is one of the common malignancies in women in the world. In recent years, increased expression of Notch signaling has been reported in cervical cancer cells and cervical carcinomas [59, 82–84]. Moreover, the NICD expression was higher in cervical cancers with high grade, lymph node involvement and parametrial invasion [85]. It has been accepted that high-risk human papillomaviruses (HPV) was involved in the progression of cervical cancer, and interestingly HPV E6 and E7 protein expression was found to be causally related with up-regulation in Notch-1 expression human cervical carcinoma cell line [86]. Moreover, activation of NICD, Hes-1, and Jagged-1 was observed in the majority of cervical cancer, and was accompanied by activation of the NF-κB pathway [87]. Song, et al. recently reported that over-expression of Notch-1 stimulates NF-κB activity in CaSki cervical cancer cells by associating with the IKK signalosome through IKKα [83]. Interestingly, several studies have shown that high expression of Notch-1 leads to growth arrest of cervical cancer cells [88–91], suggesting the complexity of the role of Notch signaling in the context of human cervical cancers. Recently, an excellent review about the role of Notch signaling in human cervical cancer has been published [92]. Therefore, we will not discuss the functions of Notch signaling in human cervical cancer in detail in this article and the readers are referred to the published review article.

GASTRIC CANCER

Gastric carcinoma is one of the most common cancers and lethal malignancies in the world. Notch signaling pathway was found to be involved in controlling the progression of gastric cancer. The expression of Notch-1 was significantly higher in gastric cancer than in normal gastric tissue, and it was found to be closely associated with tumor size, differentiation grade, depth of invasion and vessel invasion. The three-year survival rate was significantly higher in Notch-1 negative patients than in Notch-1 positive patients, suggesting that Notch-1 may be a novel prognostic marker of gastric cancer [93] and in fact could become a novel target for gastric cancer therapy. In addition, patients with Jagged-1 expression in gastric cancer tissues had a poor survival rate compared to those without Jagged-1 expression [94], suggesting that Jagged-1 may be another prognostic marker in gastric cancer, and as such could also be a novel target for therapy. Recently, the mechanisms on how Notch signaling plays important roles in gastric cancer have been reported by Yeh, et al. who showed that activation of Notch-1 signal pathway promotes progression of gastric cancer, at least in part through COX-2 expression [94]. Moreover, Ji, et al. found that miR-34 restoration in gastric cancer Kato III cells reduced the expression of target genes Notch-1-4 [95], suggesting that the regulation of Notch receptors by specific microRNA could become a novel and targeted approach for the treatment of gastric cancer, and thus further in-depth research in this area is urgently needed.

OTHER CANCERS

Emerging evidences clearly suggest that the Notch protein signaling network is frequently deregulated in human malignancies such as prostate cancer, pancreatic cancer, lung cancer, breast cancer, glioblastoma, cervical cancer, skin cancer, human hepatocellular carcinoma, colon cancer, renal cancer, head and neck, acute myeloid, Hodgkin and large-cell lymphomas, thyroid cancer, and gastric cancer. The readers who are interested in learning more on the role of Notch signaling in human malignancies that we did not discussed here could be referred to excellent review articles that have been published on this subject [7, 9, 96–98].

NOTCH AS A CANCER TREATMENT TARGET

Based on the above mentioned information regarding the growing body of published literature on the role of Notch in human malignancies, we strongly believe that deregulation of Notch signaling is a key feature of many human cancers. In most cases, its deregulation has an oncogenic function. As a result, inactivation of Notch signaling by novel approaches is likely to have a significant impact on cancer therapy. However, it is important to note that the effects of Notch are remarkably context dependent, which suggest that the exploitation of Notch signaling could be used for different purposes in different cell types, and thus systemic inhibition of Notch signaling could be useful in only those situations where Notch is activated. Another strategy could be to select effective drug combinations, or design more selective delivery for Notch inhibitors in the target tissue to avoid systemic toxicity [7]. Since Notch signaling plays critical roles in cancer stem cells (CSCs) and because current cancer therapeutics do not usually target CSCs but they only kills differentiated tumor cells that make up the bulk of the tumor, thus the killing of rare CSC population is of paramount importance, which could be accomplished by Notch-targeted therapy. Therefore eradication of CSCs by novel approaches is increasingly being recognized as an important goal in curing cancer and that effort Notch-targeted agents could be very useful for the complete eradication tumors.

To that end, Notch signaling could be inhibited theoretically at many different levels. It is possible to interfere with Notch-ligand interactions, receptor activation, mono-ubiquitination, NICD nuclear complex formation and inhibition of its translocation to the nuclear compartment Fig. (3). Notch signaling is activated via the activity of γ-secretase which became a target in cancer therapy. Several forms of γ-secretase inhibitors have been tested for antitumor effects. In recent years, it has been reported that GSI inhibited cell growth and induced apoptosis in many human cancer cells, such as Kaposi’s sarcoma cells, hepatoma cells, breast cancer cells, pancreatic cancer cells, and myeloma cells [62, 99–102]. Recently, it was found that inhibition of Notch signaling with GSI sensitized cells to chemotherapy and was synergistic with oxaliplatin and 5-FU, suggesting that combining GSI with chemotherapy may represent a novel approach for treating metastatic colon cancers [55]. Very recently,

Fig. 3.

Diagram of putative therapeutic target in the Notch pathway. Notch signaling could be inhibited theoretically at many different levels. It is possible to (1) interfere with Notch-ligand interactions, (2) inhibit receptor activation, (3) promote Notch ubiquitination and degradation, (4) inhibit its translocation to the nuclear compartment and (5) inhibit NICD nuclear complex formation.

Real et al. reported that combination therapy with GSI plus glucocorticoids can improve the anti-leukemic effects of GSI and reduce their gut toxicity [72]. We also found that a GSI suppressed prostate cancer cell growth [103]. Inhibitors of γ-secretase are being tested in Phase I clinical trials, suggesting that Notch signaling proteins are an important targets in cancer therapy. However, one of the major challenges is to eliminate unwanted toxicity associated with the GSI, especially the cytotoxicity in the gastrointestinal tract.

To that end, studies from our laboratory have shown that chemopreventive “natural agents” such as genistein and curcumin (non-toxic agents from dietary sources) may inhibit Notch-1 activation in pancreatic cancer cells leading to apoptotic cell death [19, 104, 105]. In addition, studies from other laboratories have shown that resveratrol, another non-toxic dietary “natural agent” induced apoptosis by inhibiting the Notch pathway mediated by p53 and PI3K/Akt in T-ALL [106]. Moreover, one Chinese herb antitumor B also inhibited Notch expression in a mouse lung tumor model [107]. These limited yet provocative findings suggest that inhibition of Notch-1, especially by genistein or curcumin could be a novel therapeutic approach for the prevention of tumor progression and/or treatment of human malignancies by targeting the inactivation of Notch signaling proteins. Collectively, our findings together with those reported in the literature are becoming an exciting area for further in-depth research toward targeted inactivation of Notch signaling proteins, especially by genistein, resveratrol, curcumin and others, as a novel therapeutic approach for eradicating human malignancies, which in fact could be due to the selective killing of CSCs.

CONCLUSIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

In this review article we attempted to summarize the role of Notch proteins in human malignancies; however we could not cite all published studies, and thus we sincerely apologize to those whose work has not been cited here due to space limitations. In conclusion, deregulation of Notch proteins has been correlated with the development and progression of cancer, and during the acquisition of EMT phenotype, and the formation of cancer stem cells Fig. (4). Importantly, Notch pathway has been characterized as the biomarkers for diagnosis and prognosis, as well as targets for cancer therapy. More importantly, “natural agents” could be useful for targeting Notch signaling pathway proteins, which in turn could enhance the efficacy of conventional cancer therapies. Therefore, targeting Notch signaling by “natural agents” could also open newer avenues to eradicate tumors by eliminating CSCs toward successful treatment of cancer. It is our perspectives that “natural” agents such as curcumin, isoflavone, resveratrol, etc could inhibit Notch signaling, which could lead to the inhibition of cancer growth, induction of apoptosis, reversal of EMT phenotype, and increasing drug sensitivity. Therefore, down-regulation of Notch pathway by “natural agents” could be helpful for the prevention of tumor progression and/or treatment of human cancers especially because “natural agents” are generally non-toxic and they could be useful for targeted elimination of drug-resistant CSCs, which would be useful for complete eradication of tumor cells in patients diagnosed with cancer.

Fig. 4.

The role of Notch signaling pathway in the development and progression of cancer, and during the acquisition of EMT phenotype, and the formation of cancer stem cells. Natural agents and γ-secretase inhibitors could be useful for targeting Notch signaling pathway proteins, which could enhance the efficacy of conventional cancer therapies.

Acknowledgments

The authors’ work cited in this review was funded by grants from the National Cancer Institute, NIH (5R01CA-101870, 5R01CA131151, 5R01CA083695) to F.H.S. and Department of Defense Postdoctoral Training Award W81X-WH-08-1-0196 (Zhiwei Wang) and also partly supported by a subcontract award (F.H.S.) from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center through a SPORE grant (5P20-CA101936) on pancreatic cancer awarded to James Abbruzzese. We also sincerely thank both Puschelberg and Guido foundation for their generous contributions to our research.

References

- 1.Miele L, Osborne B. Arbiter of differentiation and death: Notch signaling meets apoptosis. J Cell, Physiol. 1999;181:393–409. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199912)181:3<393::AID-JCP3>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miele L. Notch signaling. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:1074–1079. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weinmaster G. The ins and outs of notch signaling. Mol Cell, Neurosci. 1997;9:91–102. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1997.0612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kopan R, Ilagan MX. The canonical Notch signaling pathway: unfolding the activation mechanism. Cell. 2009;137:216–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fortini ME. Notch signaling: the core pathway and its posttranslational regulation. Dev Cell. 2009;16:633–647. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miele L, Miao H, Nickoloff BJ. Notch signaling as a novel cancer therapeutic target. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2006;6:313–323. doi: 10.2174/156800906777441771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rizzo P, Osipo C, Foreman K, Golde T, Osborne B, Miele L. Rational targeting of Notch signaling in cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:5124–5131. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Z, Li Y, Banerjee S, Sarkar FH. Exploitation of the Notch signaling pathway as a novel target for cancer therapy. Anti-Cancer Res. 2008;28:3621–3630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dotto GP. Notch tumor suppressor function. Oncogene. 2008;27:5115–5123. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buchler P, Gazdhar A, Schubert M, Giese N, Reber HA, Hines OJ, Giese T, Ceyhan GO, Muller M, Buchler MW, Friess H. The Notch signaling pathway is related to neurovascular progression of pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg. 2005;242:791–800. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000189115.94847.f1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miyamoto Y, Maitra A, Ghosh B, Zechner U, Argani P, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Sriuranpong V, Iso T, Meszoely IM, Wolfe MS, Hruban RH, Ball DW, Schmid RM, Leach SD. Notch mediates TGF alpha-induced changes in epithelial differentiation during pancreatic tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:565–576. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00140-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De La OJ, Emerson LL, Goodman JL, Froebe SC, Illum BE, Curtis AB, Murtaugh LC. Notch and Kras reprogram pancreatic acinar cells to ductal intraepithelial neoplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:18907–18912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810111105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De La OJ, Murtaugh LC. Notch and Kras in pancreatic cancer: at the crossroads of mutation, differentiation and signaling. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1860–1864. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.12.8744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kimura K, Satoh K, Kanno A, Hamada S, Hirota M, Endoh M, Masamune A, Shimosegawa T. Activation of Notch signaling in tumorigenesis of experimental pancreatic cancer induced by dimethylbenzanthracene in mice. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:155–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00369.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mullendore ME, Koorstra JB, Li YM, Offerhaus GJ, Fan X, Henderson CM, Matsui W, Eberhart CG, Maitra A, Feldmann G. Ligand-dependent Notch signaling is involved in tumor initiation and tumor maintenance in pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2291–2301. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sawey ET, Johnson JA, Crawford HC. Matrix metalloproteinase 7 controls pancreatic acinar cell transdifferentiation by activating the Notch signaling pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19327–19332. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705953104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Z, Banerjee S, Li Y, Rahman KM, Zhang Y, Sarkar FH. Down-regulation of Notch-1 inhibits invasion by inactivation of nuclear factor-{kappa}B, vascular endothelial growth factor, and matrix metalloproteinase-9 in pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2778–2784. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Z, Zhang Y, Li Y, Banerjee S, Liao J, Sarkar FH. Down-regulation of Notch-1 contributes to cell growth inhibition and apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:483–493. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Z, Li Y, Kong D, Banerjee S, Ahmad A, Azmi AS, Ali S, Abbruzzese JL, Gallick GE, Sarkar FH. Acquisition of epithelial-mesenchymal transition phenotype of gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic cancer cells is linked with activation of the notch signaling pathway. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2400–2407. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ji Q, Hao X, Zhang M, Tang W, Yang M, Li L, Xiang D, Desano JT, Bommer GT, Fan D, Fearon ER, Lawrence TS, Xu L. MicroRNA miR-34 inhibits human pancreatic cancer tumor-initiating cells. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6816. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shou J, Ross S, Koeppen H, de Sauvage FJ, Gao WQ. Dynamics of notch expression during murine prostate development tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7291–7297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bin HB, Adhami VM, Asim M, Siddiqui IA, Bhat KM, Zhong W, Saleem M, Din M, Setaluri V, Mukhtar H. Targeted knockdown of Notch1 inhibits invasion of human prostate cancer cells concomitant with inhibition of matrix metalloproteinase-9 and urokinase plasminogen activator. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:452–459. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Villaronga MA, Bevan CL, Belandia B. Notch signaling: a potential therapeutic target in prostate cancer. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2008;8:566–580. doi: 10.2174/156800908786241096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leong KG, Gao WQ. The Notch pathway in prostate development and cancer. Differentiation. 2008;76:699–716. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2008.00288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zayzafoon M, Abdulkadir SA, McDonald JM. Notch signaling and ERK activation are important for the osteomimetic properties of prostate cancer bone metastatic cell lines. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:3662–3670. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308158200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Santagata S, Demichelis F, Riva A, Varambally S, Hofer MD, Kutok JL, Kim R, Tang J, Montie JE, Chinnaiyan AM, Rubin MA, Aster JC. JAGGED1 expression is associated with prostate cancer metastasis and recurrence. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6854–6857. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y, Wang Z, Ahmed F, Banerjee S, Li Y, Sarkar FH. Down-regulation of Jagged-1 induces cell growth inhibition and S phase arrest in prostate cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2006;119(9):2071–2077. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alimirah F, Panchanathan R, Davis FJ, Chen J, Choubey D. Restoration of p53 expression in human cancer cell lines upregulates the expression of Notch1: implications for cancer cell fate determination after genotoxic stress. Neoplasia. 2007;9:427–434. doi: 10.1593/neo.07211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nantermet PV, Xu J, Yu Y, Hodor P, Holder D, Adamski S, Gentile MA, Kimmel DB, Harada S, Gerhold D, Freedman LP, Ray WJ. Identification of genetic pathways activated by the androgen receptor during the induction of proliferation in the ventral prostate gland. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:1310–1322. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310206200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Belandia B, Powell SM, Garcia-Pedrero JM, Walker MM, Bevan CL, Parker MG. Hey1 a mediator of notch signaling is an androgen receptor corepressor. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:1425–1436. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.4.1425-1436.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu F, Stutzman A, Mo YY. Notch signaling and its role in breast cancer. Front Biosci. 2007;12:4370–4383. doi: 10.2741/2394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stylianou S, Clarke RB, Brennan K. Aberrant activation of notch signaling in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1517–1525. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reedijk M, Odorcic S, Chang L, Zhang H, Miller N, McCready DR, Lockwood G, Egan SE. High-level coexpression of JAG1 and NOTCH1 is observed in human breast cancer and is associated with poor overall survival. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8530–8537. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mungamuri SK, Yang X, Thor AD, Somasundaram K. Survival signaling by Notch1: mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)-dependent inhibition of p53. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4715–4724. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee CW, Simin K, Liu Q, Plescia J, Guha M, Khan A, Hsieh CC, Altieri DC. A functional Notch-survivin gene signature in basal breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10:R97. doi: 10.1186/bcr2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rizzo P, Miao H, D’Souza G, Osipo C, Song LL, Yun J, Zhao H, Mascarenhas J, Wyatt D, Antico G, Hao L, Yao K, Rajan P, Hicks C, Siziopikou K, Selvaggi S, Bashir A, Bhandari D, Marchese A, Lendahl U, Qin JZ, Tonetti DA, Albain K, Nickoloff BJ, Miele L. Cross-talk between notch and the estrogen receptor in breast cancer suggests novel therapeutic approaches. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5226–5235. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leong KG, Niessen K, Kulic I, Raouf A, Eaves C, Pollet I, Karsan A. Jagged1-mediated Notch activation induces epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition through Slug-induced repression of E-cadherin. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2935–2948. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Neill CF, Urs S, Cinelli C, Lincoln A, Nadeau RJ, Leon R, Toher J, Mouta-Bellum C, Friesel RE, Liaw L. Notch2 signaling induces apoptosis and inhibits human MDA-MB-231 xenograft growth. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:1023–1036. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamaguchi N, Oyama T, Ito E, Satoh H, Azuma S, Hayashi M, Shimizu K, Honma R, Yanagisawa Y, Nishikawa A, Kawamura M, Imai J, Ohwada S, Tatsuta K, Inoue J, Semba K, Watanabe S. NOTCH3 signaling pathway plays crucial roles in the proliferation of ErbB2-negative human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1881–1888. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Phillips TM, Kim K, Vlashi E, McBride WH, Pajonk F. Effects of recombinant erythropoietin on breast cancer-initiating cells. Neoplasia. 2007;9:1122–1129. doi: 10.1593/neo.07694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Farnie G, Clarke RB. Mammary stem cells and breast cancer--role of Notch signalling. Stem Cell Rev. 2007;3:169–175. doi: 10.1007/s12015-007-0023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Collins BJ, Kleeberger W, Ball DW. Notch in lung development and lung cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2004;14:357–364. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sriuranpong V, Borges MW, Ravi RK, Arnold DR, Nelkin BD, Baylin SB, Ball DW. Notch signaling induces cell cycle arrest in small cell lung cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3200–3205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen H, Thiagalingam A, Chopra H, Borges MW, Feder JN, Nelkin BD, Baylin SB, Ball DW. Conservation of the Drosophila lateral inhibition pathway in human lung cancer: a hairy-related protein (HES-1) directly represses achaetescute homolog-1 expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5355–5360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen Y, De Marco MA, Graziani I, Gazdar AF, Strack PR, Miele L, Bocchetta M. Oxygen concentration determines the biological effects of NOTCH-1 signaling in adenocarcinoma of the lung. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7954–7959. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dang TP, Eichenberger S, Gonzalez A, Olson S, Carbone DP. Constitutive activation of Notch3 inhibits terminal epithelial differentiation in lungs of transgenic mice. Oncogene. 2003;22:1988–1997. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dang TP, Gazdar AF, Virmani AK, Sepetavec T, Hande KR, Minna JD, Roberts JR, Carbone DP. Chromosome 19 translocation, overexpression of Notch3, and human lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1355–1357. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.16.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Konishi J, Kawaguchi KS, Vo H, Haruki N, Gonzalez A, Carbone DP, Dang TP. Gamma-secretase inhibitor prevents Notch3 activation and reduces proliferation in human lung cancers. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8051–8057. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haruki N, Kawaguchi KS, Eichenberger S, Massion PP, Olson S, Gonzalez A, Carbone DP, Dang TP. Dominant-negative Notch3 receptor inhibits mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway and the growth of human lung cancers. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3555–3561. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Radtke F, Clevers H. Self-renewal and cancer of the gut: two sides of a coin. Science. 2005;307:1904–1909. doi: 10.1126/science.1104815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reedijk M, Odorcic S, Zhang H, Chetty R, Tennert C, Dickson BC, Lockwood G, Gallinger S, Egan SE. Activation of Notch signaling in human colon adenocarcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2008;33:1223–1229. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Akiyoshi T, Nakamura M, Yanai K, Nagai S, Wada J, Koga K, Nakashima H, Sato N, Tanaka M, Katano M. Gamma-secretase inhibitors enhance taxane-induced mitotic arrest and apoptosis in colon cancer cells. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:131–144. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fre S, Pallavi SK, Huyghe M, Lae M, Janssen KP, Robine S, Rtavanis-Tsakonas S, Louvard D. Notch and Wnt signals cooperatively control cell proliferation and tumorigenesis in the intestine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:6309–6314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900427106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Meng RD, Shelton CC, Li YM, Qin LX, Notterman D, Paty PB, Schwartz GK. Gamma-Secretase inhibitors abrogate oxaliplatin-induced activation of the Notch-1 signaling pathway in colon cancer cells resulting in enhanced chemosensitivity. Cancer Res. 2009;69:573–582. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ghaleb AM, Aggarwal G, Bialkowska AB, Nandan MO, Yang VW. Notch inhibits expression of the Kruppel-like factor 4 tumor suppressor in the intestinal epithelium. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6:1920–1927. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sjolund J, Johansson M, Manna S, Norin C, Pietras A, Beckman S, Nilsson E, Ljungberg B, Axelson H. Suppression of renal cell carcinoma growth by inhibition of Notch signaling in vitro and in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:217–228. doi: 10.1172/JCI32086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Patel NS, Li JL, Generali D, Poulsom R, Cranston DW, Harris AL. Up-regulation of delta-like 4 ligand in human tumor vasculature and the role of basal expression in endothelial cell function. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8690–8697. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sun S, Du R, Gao J, Ning X, Xie H, Lin X, Liu J, Fan D. Expression and clinical significance of Notch receptors in human renal cell carcinoma. Pathology. 2009;41:335–341. doi: 10.1080/00313020902885003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Qi R, An H, Yu Y, Zhang M, Liu S, Xu H, Guo Z, Cheng T, Cao X. Notch1 signaling inhibits growth of human hepatocellular carcinoma through induction of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2003;63:8323–8329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang C, Qi R, Li N, Wang Z, An H, Zhang Q, Yu Y, Cao X. Notch1 signaling sensitizes tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-induced apoptosis in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells by inhibiting Akt/Hdm2-mediated p53 degradation and up-regulating p53-dependent DR5 expression. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:16183–16190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.002105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 62.Suwanjunee S, Wongchana W, Palaga T. Inhibition of gamma-secretase affects proliferation of leukemia and hepatoma cell lines through Notch signaling. Anticancer Drugs. 2008;19:477–486. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e3282fc6cdd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Giovannini C, Lacchini M, Gramantieri L, Chieco P, Bolondi L. Notch3 intracellular domain accumulates in HepG2 cell line. Anti Cancer Res. 2006;26:2123–2127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hainaud P, Contreres JO, Villemain A, Liu LX, Plouet J, Tobelem G, Dupuy E. The role of the vascular endothelial growth factor-Delta-like 4 ligand/Notch4-ephrin B2 cascade in tumor vessel remodeling and endothelial cell functions. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8501–8510. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang M, Xue L, Cao Q, Lin Y, Ding Y, Yang P, Che L. Expression of Notch1, Jagged1 and beta-catenin and their clinicopathological significance in hepatocellular carcinoma. Neoplasma. 2009;56:533–541. doi: 10.4149/neo_2009_06_533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gao J, Song Z, Chen Y, Xia L, Wang J, Fan R, Du R, Zhang F, Hong L, Song J, Zou X, Xu H, Zheng G, Liu J, Fan D. Deregulated expression of Notch receptors in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Liver Dis. 2008;40:114–121. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gao J, Chen C, Hong L, Wang J, Du Y, Song J, Shao X, Zhang J, Han H, Liu J, Fan D. Expression of Jagged1 and its association with hepatitis B virus X protein in hepatocellular carcinoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;356:341–347. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.02.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gramantieri L, Giovannini C, Lanzi A, Chieco P, Ravaioli M, Venturi A, Grazi GL, Bolondi L. Aberrant Notch3 and Notch4 expression in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2007;27:997–1007. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2007.01544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cantarini MC, de la Monte SM, Pang M, Tong M, D’Errico A, Trevisani F, Wands JR. Aspartyl-asparagyl beta hydroxylase over-expression in human hepatoma is linked to activation of insulin-like growth factor and notch signaling mechanisms. Hepatology. 2006;44:446–457. doi: 10.1002/hep.21272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ellisen LW, Bird J, West DC, Soreng AL, Reynolds TC, Smith SD, Sklar J. TAN-1, the human homolog of the Drosophila notch gene, is broken by chromosomal translocations in T lymphoblastic neoplasms. Cell. 1991;66:649–661. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90111-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Demarest RM, Ratti F, Capobianco AJ. It’s T-ALL about Notch. Oncogene. 2008;27:5082–5091. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Real PJ, Ferrando AA. Notch inhibition and glucocorticoid therapy in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2009;23:1374–1377. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Grabher C, von BH, Look AT. Notch 1 activation in the molecular pathogenesis of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:347–359. doi: 10.1038/nrc1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jundt F, Schwarzer R, Dorken B. Notch signaling in leukemias and lymphomas. Curr Mol Med. 2008;8:51–59. doi: 10.2174/156652408783565540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shih AH, Holland EC. Notch signaling enhances nestin expression in gliomas. Neoplasia. 2006;8:1072–1082. doi: 10.1593/neo.06526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kanamori M, Kawaguchi T, Nigro JM, Feuerstein BG, Berger MS, Miele L, Pieper RO. Contribution of Notch signaling activation to human glioblastoma multiforme. J Neurosurg. 2007;106:417–427. doi: 10.3171/jns.2007.106.3.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hulleman E, Quarto M, Vernell R, Masserdotti G, Colli E, Kros JM, Levi D, Gaetani P, Tunici P, Finocchiaro G, Baena RR, Capra M, Helin K. A role for the transcription factor HEY1 in glioblastoma. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:136–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00307.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sivasankaran B, Degen M, Ghaffari A, Hegi ME, Hamou MF, Ionescu MC, Zweifel C, Tolnay M, Wasner M, Mergenthaler S, Miserez AR, Kiss R, Lino MM, Merlo A. Tenascin-C is a novel RBPJkappa-induced target gene for Notch signaling in gliomas. Cancer Res. 2009;69:458–465. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shiras A, Chettiar ST, Shepal V, Rajendran G, Prasad GR, Shastry P. Spontaneous transformation of human adult nontumorigenic stem cells to cancer stem cells is driven by genomic instability in a human model of glioblastoma. Stem Cells. 2007;25:1478–1489. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jeon HM, Jin X, Lee JS, Oh SY, Sohn YW, Park HJ, Joo KM, Park WY, Nam DH, DePinho RA, Chin L, Kim H. Inhibitor of differentiation 4 drives brain tumor-initiating cell genesis through cyclin E and notch signaling. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2028–2033. doi: 10.1101/gad.1668708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Li Y, Guessous F, Zhang Y, Dipierro C, Kefas B, Johnson E, Marcinkiewicz L, Jiang J, Yang Y, Schmittgen TD, Lopes B, Schiff D, Purow B. MicroRNA-34a inhibits glioblastoma growth by targeting multiple oncogenes. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7569. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Daniel B, Rangarajan A, Mukherjee G, Vallikad E, Krishna S. The link between integration and expression of human papillomavirus type 16 genomes and cellular changes in the evolution of cervical intraepithelial neoplastic lesions. J Gen Virol. 1997;78(Pt 5):1095–1101. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-5-1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Song LL, Peng Y, Yun J, Rizzo P, Chaturvedi V, Weijzen S, Kast WM, Stone PJ, Santos L, Loredo A, Lendahl U, Sonenshein G, Osborne B, Qin JZ, Pannuti A, Nickoloff BJ, Miele L. Notch-1 associates with IKKalpha and regulates IKK activity in cervical cancer cells. Oncogene. 2008;27:5833–5844. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zagouras P, Stifani S, Blaumueller CM, Carcangiu ML, rtavanis-Tsakonas S. Alterations in Notch signaling in neoplastic lesions of the human cervix. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6414–6418. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sun XM, Wen HW, Chen CL, Liao QP. Expression of Notch intracellular domain in cervical cancer and effect of DAPT on cervical cancer cell. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 2009;44:369–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Weijzen S, Zlobin A, Braid M, Miele L, Kast WM. HPV16 E6 and E7 oncoproteins regulate Notch-1 expression and cooperate to induce transformation. J Cell Physiol. 2003;194:356–362. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ramdass B, Maliekal T, Lakshmi S, Rehman M, Rema P, Nair P, Mukherjee G, Reddy BK, Krishna S, Radhakrishna PM. Coexpression of Notch1 and NF-kappaB signaling pathway components in human cervical cancer progression. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;104:352–361. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wang L, Qin H, Chen B, Xin X, Li J, Han H. Overexpressed active Notch1 induces cell growth arrest of HeLa cervical carcinoma cells. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007;17:1283–1292. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Talora C, Cialfi S, Segatto O, Morrone S, Kim CJ, Frati L, Paolo DG, Gulino A, Screpanti I. Constitutively active Notch1 induces growth arrest of HPV-positive cervical cancer cells via separate signaling pathways. Exp Cell Res. 2005;305:343–354. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Talora C, Sgroi DC, Crum CP, Dotto GP. Specific down-modulation of Notch1 signaling in cervical cancer cells is required for sustained HPV-E6/E7 expression and late steps of malignant transformation. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2252–2263. doi: 10.1101/gad.988902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yao J, Duan L, Fan M, Yuan J, Wu X. Notch1 induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in human cervical cancer cells: involvement of nuclear factor kappa B inhibition. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007;17:502–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.00872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Maliekal TT, Bajaj J, Giri V, Subramanyam D, Krishna S. The role of Notch signaling in human cervical cancer: implications for solid tumors. Oncogene. 2008;27:5110–5114. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Li DW, Wu Q, Peng ZH, Yang ZR, Wang Y. Expression and Significance of Notch1 and PTEN in Gastric Cancer. Ai Zheng. 2007;26:1183–1187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yeh TS, Wu CW, Hsu KW, Liao WJ, Yang MC, Li AF, Wang AM, Kuo ML, Chi CW. The activated Notch1 signal pathway is associated with gastric cancer progression through cyclooxygenase-2. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5039–5048. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ji Q, Hao X, Meng Y, Zhang M, Desano J, Fan D, Xu L. Restoration of tumor suppressor miR-34 inhibits human p53-mutant gastric cancer tumorspheres. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:266. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kunnimalaiyaan M, Chen H. Tumor suppressor role of Notch-1 signaling in neuroendocrine tumors. Oncologist. 2007;12:535–542. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-5-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.D’Souza B, Miyamoto A, Weinmaster G. The many facets of Notch ligands. Oncogene. 2008;27:5148–5167. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dufraine J, Funahashi Y, Kitajewski J. Notch signaling regulates tumor angiogenesis by diverse mechanisms. Oncogene. 2008;27:5132–5137. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Nefedova Y, Sullivan DM, Bolick SC, Dalton WS, Gabrilovich DI. Inhibition of Notch signaling induces apoptosis of myeloma cells and enhances sensitivity to chemotherapy. Blood. 2008;111:2220–2229. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-102632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Curry CL, Reed LL, Golde TE, Miele L, Nickoloff BJ, Foreman KE. Gamma secretase inhibitor blocks Notch activation and induces apoptosis in Kaposi’s sarcoma tumor cells. Oncogene. 2005;24:6333–6344. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Osipo C, Patel P, Rizzo P, Clementz AG, Hao L, Golde TE, Miele L. ErbB-2 inhibition activates Notch-1 and sensitizes breast cancer cells to a gamma-secretase inhibitor. Oncogene. 2008;27:5019–5032. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Plentz R, Park JS, Rhim AD, Abravanel D, Hezel AF, Sharma SV, Gurumurthy S, Deshpande V, Kenific C, Settleman J, Majumder PK, Stanger BZ, Bardeesy N. Inhibition of gamma-secretase activity inhibits tumor progression in a mouse model of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1741–1749. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zhang Y, Wang Z, Ahmed F, Banerjee S, Li Y, Sarkar FH. Down-regulation of Jagged-1 induces cell growth inhibition and S phase arrest in prostate cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:2071–2077. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wang Z, Zhang Y, Banerjee S, Li Y, Sarkar FH. Notch-1 down-regulation by curcumin is associated with the inhibition of cell growth and the induction of apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer. 2006;106:2503–2513. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wang Z, Zhang Y, Banerjee S, Li Y, Sarkar FH. Inhibition of nuclear factor kappab activity by genistein is mediated via Notch-1 signaling pathway in pancreatic cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1930–1936. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Cecchinato V, Chiaramonte R, Nizzardo M, Cristofaro B, Basile A, Sherbet GV, Comi P. Resveratrol-induced apoptosis in human T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia MOLT-4 cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;74:1568–1574. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zhang Z, Wang Y, Yao R, Li J, Yan Y, La RM, Lemon WL, Grubbs CJ, Lubet RA, You M. Cancer chemopreventive activity of a mixture of Chinese herbs (antitumor B) in mouse lung tumor models. Oncogene. 2004;23:3841–3850. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]