Abstract

RNA interference (RNAi) mediated by short hairpin-RNA (shRNA) expressing plasmids can induce specific and long-term knockdown of specific mRNAs in eukaryotic cells. To develop a vector-based RNAi model for Schistosoma mansoni, the schistosome U6 gene promoter was employed to drive expression of shRNA targeting reporter firefly luciferase. An upstream region of a U6 gene predicted to contain the promoter was amplified from genomic DNA of S. mansoni. A shRNA construct driven by the predicted U6 promoter targeting luciferase was assembled and cloned into plasmid pXL-Bac II, the construct termed pXL-BacII_SmU6-shLuc. Luciferase expression in transgenic fibrosarcoma HT-1080 cells was significantly reduced 96 h following transduction with plasmid pXL-BacII_SmU6-shLuc, which encodes luciferase mRNA-specific shRNA. In a similar fashion, schistosomules of S. mansoni were transformed with the SmU6-shLuc or control constructs. Firefly luciferase mRNA was introduced into transformed schistosomules after which luciferase activity was analyzed. Significantly less activity was present in schistosomules transfected with pXL-BacII_SmU6-shLuc compared with controls. The findings revealed that the putative S. mansoni U6 gene promoter of 270 bp in length was active in human cells and schistosomes. Given that the U6 gene promoter drove expression of shRNA from an episome, the findings also indicate the potential of this putative RNA polymerase III dependent promoter as a component regulatory element in vector-based RNAi for functional genomics of schistosomes.

Keywords: Schistosome, Luciferase, RNA interference, U6 gene, Vector-based RNAi, Promoter

1. Introduction

Draft genomes of Schistosoma japonicum and Schistosoma mansoni were reported recently (Schistosoma japonicum Genome Sequencing and Functional Analysis Consortium, 2009; Berriman et al., 2009). New information in genome sequences will provide leads for development of new interventions for control and treatment of schistosomiasis (Brindley et al., 2009), which relies solely of the anthelmintic drug praziquantel at this time. Tools are in development to determine the importance of the new genomic sequences of schistosomes (Beckmann et al., 2007; Brindley and Pearce 2007; Kines et al., 2008; Mann et al., 2008), although there are difficulties with investigating the complex genomes of helminth parasites such as the schistosomes in contrast to model, free-living species. RNA interference (RNAi) is active in schistosomes, has been used to investigate increasing numbers of gene targets in most developmental stages, and is being optimized for high-throughput screens (Stefanic et al., 2010 and references therein).

Despite its utility, RNAi frequently leads to only transient gene silencing and, in addition, may be inaccessible to some developmental stages and/or tissues of schistosomes. In vivo, e.g. vector-based, RNAi approaches that lead to integration of transgenes encoding cassettes that express small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) can circumvent deficiencies with exogenous RNAi approaches by providing continuous and/or conditional gene silencing (ter Brake et al., 2006; Sliva and Schnierle, 2010). Recently, it has been demonstrated that pseudotyped murine leukemia virus (MLV) can be employed to transduce developmental stages of schistosomes, leading to chromosomal integration of retroviral transgenes and transgene reporter activity (Kines et al., 2008, 2010; Yang et al., 2010). Moreover, a vector-based RNAi approach has been reported in which the MLV transgene encoded a long hairpin RNA specific for a schistosome protease involved in hemoglobinolysis (Tchoubrieva et al., 2010).

In insect, mammalian, avian and some pathogenic protozoa, RNA polymerase III (Pol III) promoter-based DNA vectors can express siRNA or short hairpin RNA (shRNA) (Brummelkamp et al., 2002; Gou et al., 2003; Wakiyama et al., 2005; Linford et al., 2009). However, this has not been demonstrated in schistosomes. Here we describe a promoter-like element from the U6 gene of S. mansoni, a Pol III, non-coding RNA gene that is a component of eukaryotic spliceosome machinery (see Copeland et al., 2009). An episomal plasmid that included a U6 gene promoter driving a short hairpin transcript designed to target mRNA encoding firefly luciferase was constructed. After transfection of human fibrosarcoma cells and schistosomules with the construct, significantly less reporter luciferase activity was seen in the transformed human cells and schistosomes. These findings demonstrated the activity of a 270 bp promoter-like sequence of the schistosome U6 non-coding RNA gene to drive transcription of short transcripts from episomes delivered to both human cells and schistosomules of S. mansoni. The findings indicate the likely utility of this U6 gene promoter containing construct for vector-based RNAi approaches in schistosomes.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Schistosomules

Biomphalaria glabrata snails infected with the NMRI (Puerto Rican) strain of S. mansoni were supplied by Dr. Fred Lewis, Biomedical Research Institute, Rockville, MD, USA. Cercariae released from infected B. glabrata snails were mechanically transformed into schistosomules. Briefly, cercariae were concentrated by centrifugation (425 g/10 min) and washed once with schistosomule wash medium, RPMI 1640 supplemented with 1× penicillin, streptomycin, fungizone (1 × PSF) and 10 mM HEPES (Mann et al., 2010). Cercarial tails were sheared off by 20 passes through 22 gauge emulsifying needles after which schistosomule bodies were isolated from tails by Percoll gradient centrifugation (Lazdins et al., 1982). Schistosomula were washed three times in wash medium and cultured for up to 2 weeks at 37°C under 5% CO2 in air in modified Basch’s medium (Basch, 1981) supplemented with washed human erythrocytes, at a density of 1 µl packed red cells per ml of culture medium (Mann et al., 2010).

2.2. Isolation of a U6 gene promoter-like sequence

The sequence and predicted structure of the U6 small nRNA of S. mansoni, GenBank accession number L25920, have been described (Gu and Reddy, 1994; Copeland et al., 2009). The 109 nucleotides (nt) of the U6 RNA were employed as the query to search the Sanger Institute’s S. mansoni shotgun reads (Sanger) database, (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/cgi-bin/blast/submitblast/s_mansoni). An identical match was located to sequences in contig shisto3397e03.p1k. Flanking sequences upstream of the copy of the U6 gene in this contig were targeted for PCR, using primers SmU6F, 5’-TATCAGTGGTCTAGATGTATGCTTG-3’, and SmU6R, 5’-GCTAATCTTCTCTGTATCGTTCCA-3’. The genome of S. mansoni includes between nine and 55 copies of the U6 gene (Copeland et al., 2009). Sequences (~474 bp) upstream and flanking the U6 gene as well as part of the 5’-terminus of the U6 gene were amplified from genomic DNA of S. mansoni (prepared as in Morales et al., 2007), cloned into the TOPO TA plasmid (Invitrogen) and the sequence identity confirmed to be identical to that in contig shisto3397e03.p1k.

2.3. Construction of shRNA expression vectors targeting firefly luciferase

The two-step PCR approach of Gou et al. (2003) and Linford et al. (2009) was utilized to construct plasmid vectors for in vivo episomal RNAi. The approach involves two rounds of PCR using one universal primer, specific for the promoter and two unique target sequences; the first oligonucleotide to add the sense strand of the shRNA, the second to add the loop region and anti-sense strand. For the hairpin sense strand sequence, we utilized 21 residues, nt 851–871, (5’-GTGCGCTGCTGGTGCCAACCC-3’-), of the firefly luciferase gene in pGL3 because this site and target sequence length have been demonstrated in earlier reports of episomal vector RNAi to lead to complete or near complete knockdown of luciferase activity in Drosophila Schneider 2 cells, NIH-3T3 mouse fibroblasts and L2 rat lung epithelia cells (Gou et al., 2003; Wakiyama et al., 2005). Two rounds of PCR were employed to generate the final shRNA constructs, using forward primer U6SF1, 5’-GCGCGCGGATCCGAGTGTATGTGCATTTGGTTG-3’, and two reverse primers, Luc851R1, 5’-TCTCTTGAAGGGTTGGCACCAGCAGCGCACGGATTT CGCAC ATCACTAAC-3’ and Luc851R2, 5’-GCGCGCCTCGAGAAAAAGTGCGCTGCTGG TGCCAA CCCTCTCTTGAA-3’. The final PCR product comprised the S. mansoni U6 promoter, the sense strand of the shRNA hairpin, a loop TTCAAGAGA (9 bp) (Brummelkamp et al., 2002) region, the antisense strand of the hairpin, and the U6 termination sequence, TTTTT (Gou et al., 2003). In addition, BamHI (GGATCC) and XhoI (CTCGAG) sites were introduced upstream of the promoter and after the TTTTT terminator, respectively, to facilitate cloning. As a control vector, we constructed a cassette where the 21 target residues (nt 851–871) of the luciferase gene were ‘scrambled’ as follows, 5’-ACCTACTGGGCAGGGAGCCGC-3’, using the same forward primer (above) and the following reverse primers, ScramLuc851 R1, 5’-TCTCTTGAAA CCTACTGGGCAGGGAGCCGCGGATTTCGCACATCACTAAC-3’; ScramLuc851 R2, 5’-GCGCGCCTCGAGAAAAAGCGGCTCCCTGCCCAGTAG GTTCTCT TGAA-3’. Thermal cycling conditions and reaction volumes of Linford et al. (2009) were employed.

The final products were sized by agarose gel electrophoresis, eluted from the gel, cleaved with BamHI and XhoI, and ligated into linearized plasmid pXL-BacII at the multiple cloning site within the transposon’s inverted terminal repeats (Li et al., 2005). Top10 Escherichia coli cells (Invitrogen) were transformed with the ligation products and transformed colonies cultured on Luria-Bertani broth (LB) agar-ampicillin (100 µg/ml). Maxipreps of plasmid DNA were prepared from single bacterial colonies using PerfectPrep Endofree Maxi Kit 5Prime, Gaithersburg, MD, USA), and concentration and purity determined with a spectrophotometer (ND-1000, NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). The nt sequences of the inserts of the vector RNAi constructs, termed pXL-BacII_SmU6-shLuc and pXL-BacII_SmU6-shScramLuc were confirmed, and assigned GenBank accession numbers HQ677838 and HQ677839, respectively.

2.4. Preparation of siRNAs, double stranded RNAs (dsRNAs) and firefly luciferase mRNA

Block-iT™ siRNA of 21 nt in length, specific for residues 851–871 of firefly luciferase (siLuc), was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Long dsRNA specific for, and spanning the full-length luciferase coding sequence of 1,672 bp was synthesized by in vitro transcription from a template amplified by PCR from the firefly luciferase gene in pGL3 (Promega), using primers (F, 5’-TAA TAC GAC TCA CTA TAG GG T GCG CCC GCG AAC GAC ATT TA-3’ and R, 5’-TAA TAC GAC TCA CTA TAG GGG CAA CCG CTT CCC CGA CTT CCT TA-3’) tailed with the T7 promoter sequence). Synthesis and downstream purification of the dsRNA was accomplished using the Megascript RNAi kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). Integrity of dsRNAs was verified visually after non-denaturing agarose gel (1%) electrophoresis. For preparation of firefly luciferase mRNAs (mLuc), in vitro transcriptions of capped RNAs from template PCR products were accomplished using the mMessage mMachine T7 Ultra kit (Ambion) (Correnti and Pearce, 2004; Rinaldi et al., 2008). dsRNA or mLuc was precipitated with 1 vol. of 5 M ammonium acetate and 2.5 vol. of 95% ethanol after which the precipitate was dissolved in water and concentration and purity determined, as above.

2.5. HT1080 cells expressing firefly luciferase

We employed a genetically modified HT1080 human fibrosarcoma cell line that constitutively expressed luciferase in these studies of vector-based RNAi. Primarily for other studies (S. Suttiprapa, V.H. Mann and P.J. Brindley, unpublished data), we constructed lentiviral vectors using the ViraPower Gateway system (Invitrogen). In brief, pLenti6/R4R2/V5-DEST, which includes a gene conferring resistance to blasticidin, was modified by insertion of the promoter of the S. mansoni spliced leader RNA gene, upstream of the firefly luciferase gene (see Kines et al., 2006). The 293FT producer cells (Invitrogen) were transformed with the construct together with packaging plasmids delivered in liposomes (Invitrogen). Pseudotyped lentivirus expressing vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) glycoprotein was harvested from culture media and concentrated by centrifugation (Sorvall SS-34 rotor) at 48,000 g for 90 min at 4°C. Pelleted virions were resuspended in Opti-MEM medium (Invitrogen) at 4°C, after which functional virion titers were determined using target HT1080 human fibrosarcoma cells (Invitrogen) in the presence of the antibiotic blasticidin (Invitrogen). To generate a stable HT1080 cell line expressing luciferase, HT1080 cells were transduced with lentivirus virions (titer, 107 transducing units per ml) in the presence of polybrene (Sigma), and blasticidin-resistant cells, expressing luciferase, selected by culturing the cells in the presence of blasticidin for 14 days. Stable cells were isolated and cryopreserved and/or expanded for use as target, luciferase expressing HT1080 cells for the vector-based RNAi studies described here.

Luciferase expressing HT1080 cells were plated at a density of 5 × 105 cells/well in 6-well plates (Corning). Fifteen hours later, the cells were transfected with four or 10 µg of plasmid pXL-BacII_SmU6-shLuc or pXL-BacII_SmU6-shScramLuc or 10 pmol siLuc using the Lipofectamine 2000 transfection system (Invitrogen). A control group of cells exposed only to lipofectamine was included. One day later the cells were washed with PBS, after which plasmid transformed cells were incubated for 96 h in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin and streptomycin. Cells were counted and lysed in CCLR buffer (Promega) in order to determine levels of luciferase activity (see section 2.7).

2.6. Transfection of schistosomules with plasmids, siRNA and dsRNA

For the studies on RNAi in schistosomes, schistosomules were transfected with plasmid, dsRNA or siLuc by square wave electroporation. Specifically, schistosomules were transferred to cuvettes (4 mm gap, BTX, San Diego, CA, USA) containing media supplemented with 1 µg siLuc, 30 µg dsRNA or 20 µg of plasmid (pXL-BacII_SmU6-shLuc or pXL-BacII_SmU6-shScramLuc) and then subjected to a square wave pulse of 125 V of 20 ms duration, using a BTX ElectroSquarePoratorTM ECM830, as previously described (Kines et al., 2010). Subsequently, the transfected worms were transferred to pre-warmed Basch’s medium and maintained in culture for 48 h until mRNA encoding firefly luciferase was introduced into the cultured worms by electroporation. After electroporation, the schistosomules were maintained in culture for 3 h and then washed free of culture media, and wet pellets of worms snap frozen and stored at −80°C.

2.7. Luciferase activity assay

HT1080 cells and schistosomules were harvested, washed three times with schistosomule wash medium and stored as wet pellets at −80°C. Pellets of schistosomules were subjected to sonication (3 × 5 s bursts, output cycle 4, Misonix Sonicator 3000, Newtown, CT 06470, USA) in 300 µl of 1× CCLR lysis buffer (Promega). Pellets of 1 × 106 HT1080 cells (cell numbers were determined by replicate counts of Trypan blue-stained cells using a hemacytometer) were lysed in 300 µl of 1× CCLR lysis buffer. The lysates were clarified by centrifugation in a microfuge at 4°C, and analyzed for luciferase activity. Aliquots of 100 µl of clarified lysate were injected into 100 µl luciferin (Promega) at 25°C, mixed and the relative light units (RLUs) determined in a tube luminometer (Sirius, Berthold, Pforzheim, Germany) 10 s later (Correnti and Pearce 2004; Kines et al., 2010). Duplicate samples were measured, with results presented as the average of the readings of RLU/s/mg of soluble schistosome protein or, for HT1080 cells, as RLU/s/103 cells. Recombinant firefly luciferase (Promega) was included as a positive control. The protein concentration in the soluble fraction of the schistosome extract was determined using the bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA kit, Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA).

2.8. Statistical analysis

Statistical comparisons were made by ANOVA. When significant differences were found among groups, a Student’s t-test between controls and treatment conditions was applied, as appropriate. P-values of ≤ 0.05 were considered to be significant and P-values of ≤0.01 highly significant.

3. Results

3.1. Promoter region of the U6 non-coding RNA gene of S. mansoni

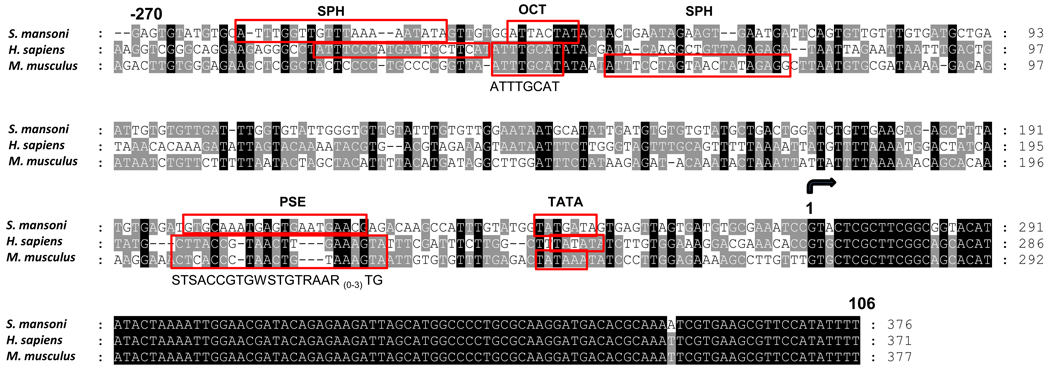

An identical match to the S. mansoni U6 gene was located in sequences in contig shisto3397e03.p1k of the draft genome assembly for S. mansoni. Flanking sequences upstream of the copy of the U6 gene in this contig were targeted for PCR (see section 2.2); ~474 bp upstream and flanking the U6 gene as well as part of the 5’-terminus of the U6 gene were amplified from genomic DNA of S. mansoni, cloned and sequenced (Fig. 1), therefore confirming the sequence identity as being identical to that in contig shisto3397e03.p1k. The 270 nt flanking and upstream of this copy of the S. mansoni U6 gene have been assigned GenBank accession number HQ540317.

Fig. 1.

Multiple sequence alignment of the U6 genes of Schistosoma mansoni, Homo sapiens and Mus musculus. The multiple alignment was assembled with ClustalW (Thompson et al., 1994) using BioEdit, version 7.0.5 (Hall, 1999) and the box shade feature of GeneDoc (Nicholas and Nicholas, 1997, Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA), and the following sequences: S. mansoni (GenBank L25920 (coding region) and HQ540317 (upstream flanking region)); human, (GenBank X07425), mouse (GenBank X06980). Residue one (black, curved arrow) is the first nucleotide (nt) of the U6 RNA gene sequence. Characteristic motifs of the enhancer and core regions of the U6 gene promoter are identified or predicted (red colored rectangles). The enhancer distal sequence element includes an octamer motif (OCT) and SphI post-octamer homology (SPH) element and the core region comprises a proximal sequence element (PSE) and a TATA-like element. Consensus sequences are indicated under the PSE and OCT motifs. Note that the relative positions for the SPH and OCT elements are reversed in mouse U6.

The putative S. mansoni U6 promoter and U6 gene were aligned with those from human (GenBank X07425) and mouse (GenBank X06980). The schistosome U6 non-coding RNA gene sequence is 96% identical to its human and murine orthologues. The sequence of the putative promoter upstream of the S. mansoni U6 gene diverged substantially from the mammalian sequences. Notwithstanding, we attempted to locate motifs characteristic of U6 gene promoters. The enhancer region, also known as the distal sequence element (DSE), consists of an octamer motif (OCT) and a SphI post-octamer homology (SPH) element. The core region comprises a proximal sequence element (PSE) and a TATA-like element (Dahlberg and Schenborn, 1988; Sturm et al., 1988; Schaub et al., 1999). Based on greater or lesser identity to the human and mouse motifs, we identified these prospective motifs of the enhancer and core regions in the 270 bp flanking the schistosome U6 gene; SPH element (21 residues), -258 ATTTGGTTGTTTAAAAATATA -238; OCT (eight residues), -230 ATTACTAT -223; PSE (21 residues), -71 GTGCAAATGAGTGAATGAACG -51; and the TATA box (seven residues), -31 TATGATA -25. These motifs are annotated on the multiple sequence alignment of the U6 genes in Fig. 1.

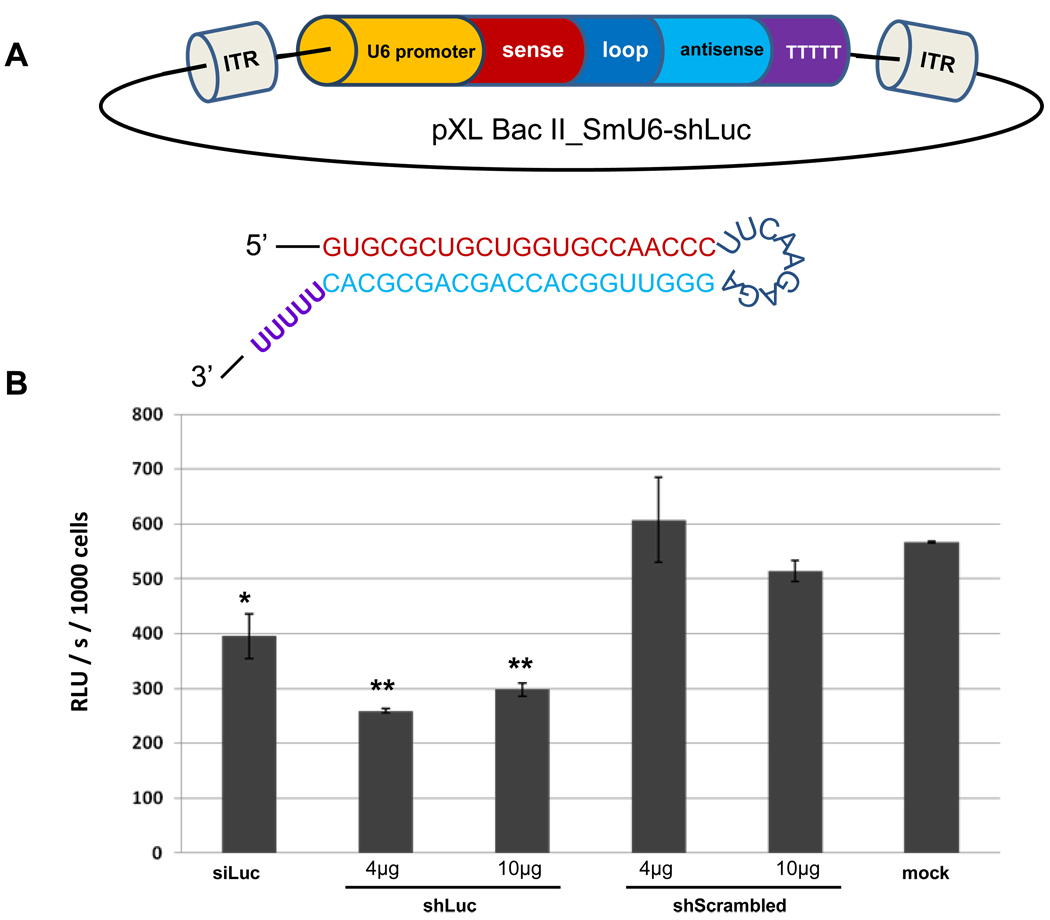

3.2. U6 promoter is active in vector-based RNAi

We constructed plasmids pXL-BacII_SmU6-shLuc and pXL-BacII_SmU6-shScramLuc (Fig. 2A). The short hairpin predicted to be transcribed from the U6 promoter of this episome includes the 21 nt sense strand specific for residues 851–871 of the luciferase transcript, a loop of nine residues, the 21 residue antisense strand, and the UUUUU termination signal. The control construct pXL-BacII_SmU6-shScramLuc includes the same residues in the target strand, but the order of the residues was scrambled. First, we transfected HT1080 cells with the vector based RNAi constructs. A HT1080 cell line that stably expressed firefly luciferase was used for this experiment, with the aim of vector-based RNAi targeting the ‘endogenous’ luciferase. At 96 h after transfection with the vector RNAi plasmids or with siRNA, statistically significant knockdown of luciferase activity was evident. In particular, luciferase activity was reduced by 54.3% and 47.5% in HT1080 cells transfected with 4 µg or 10 µg of pXL-BacII_SmU6-shLuc, respectively, compared with untreated, control HT1080 cells (both P ≤ 0.01), and by 30.2% in cells exposed to the siRNA transfected cells (P ≤ 0.05). By contrast, no reduction in luciferase activity was evident in cells transfected with the control construct, pXL-BacII_SmU6-shScramLuc (Fig. 2B). Similar findings were observed in each of two biological replicates of this experiment. These results indicated that the putative S. mansoni U6 promoter drives short hairpin expression in a human cell line against an endogenously expressed reporter gene.

Fig. 2.

Episomal vector-based RNA interference (RNAi) of firefly luciferase activity in human fibrosarcoma HT1080 cells. A) Schematic illustration of the insert of plasmid of pXL-BacII_SmU6-shLuc, including the inverted terminal repeats (ITR) flanking the short hairpin (sh)RNA cassette, the Schistosoma mansoni U6 gene promoter, the sense strand (21 nucleotide (nt), residues 851–871 of the gene encoding firefly luciferase, the nine residue loop, the 21 nt anti-sense strand and the TTTTTT terminator residues. The predicted shRNA is shown below the plasmid construct. B) Luciferase activity in HT1080 cells expressed as relative light units (RLU)/s/103 cells. HT1080 cells were transfected with 1 µg of small interfering RNA of 21 nt in length, specific for residues 851–871 of firefly luciferase (siLuc) ; 4 µg pXL-BacII_SmU6-shLuc (shLuc_4µg); 10 µg of pXL-BacII_SmU6-shLuc (shLuc_4µg); 4 µg plasmid pXL-BacII_SmU6-shScramLuc (shScrambled_4µg); 10 µg of control plasmid pXL-BacII_SmU6-shScramLuc (shScrambled_10µg); and no treatment control (mock). Bars are ± S.D. (n = 2). Significant differences between treated groups and the (mock) control are indicated: *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01.

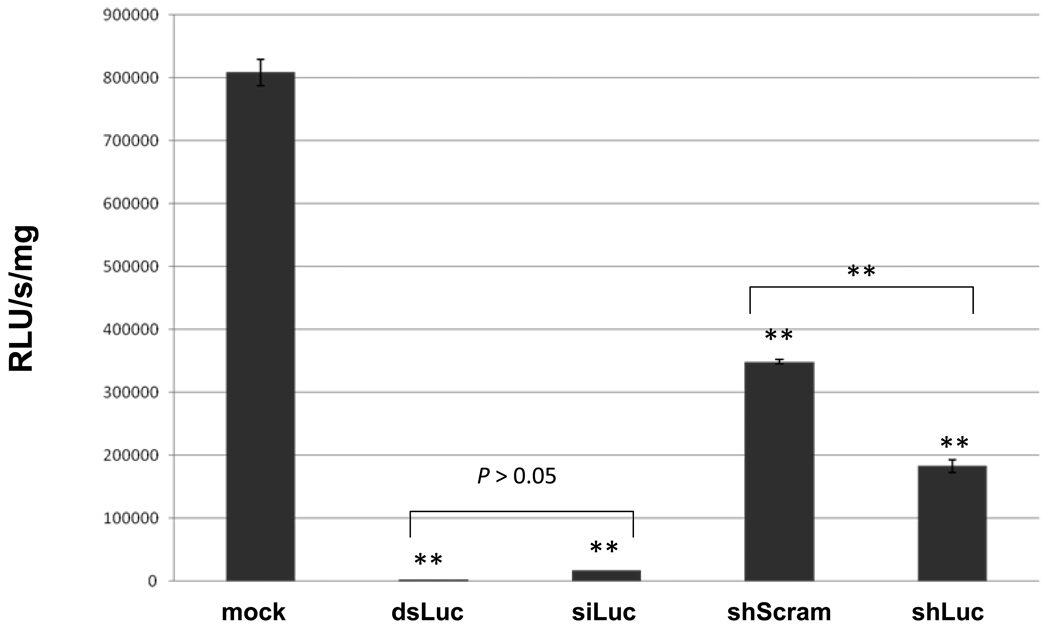

3.3. Schistosome U6 promoter-driven shRNA induces RNAi in schistosomules

The activity of pXL-BacII_SmU6-shLuc was examined in cultured schistosomules. At 48 h after transfection with the vector RNAi plasmid, or with dsRNA or siRNA, statistically significant knockdown of luciferase activity was evident. Specifically, luciferase activity was reduced by 47.5% in schistosomules transfected with 20 µg of pXL-BacII_SmU6-shLuc compared with schistosomules treated with 20 µg of the control plasmid, pXL-BacII_SmU6-shScramLuc (183,030.5 versus 348,651.3 RLU/s/mg) (P ≤ 0.05) (Fig. 3). The RNAi induced with dsRNA or siRNA was even greater than that with pXL-BacII_SmU6-shLuc, both > 95% knockdown of luciferase activity compared with the worms transfected with the control plasmid, pXL-BacII_SmU6-shScramLuc (P ≤ 0.01). More luciferase activity was seen in schistosomules not transfected with any nucleic acids (P ≤ 0.01), a control group that was termed ‘mock’ (Fig. 3). Similar findings were observed in three of four replicates of the experiment.

Fig. 3.

Episomal vector-based RNA interference (RNAi) of firefly luciferase activity in 1 day old schistosomules. Luciferase activity in schistosomules expressed as relative light units (RLU)/s/mg of protein. One day old schistosomules were electroporated in the absence of plasmid or RNAs (mock), 30 µg of firefly luciferase double stranded RNA (dsLuc), 10 µg of small interfering RNA of 21 nt in length, specific for residues 851–871 of firefly luciferase (siLuc), 20 µg of control plasmid pXL-BacII_SmU6-shScramLuc (ShScram) and 20 µg of plasmid pXL-BacII_SmU6-shLuc (shLuc). Bars are ± S.D. (n = 2). Significant differences between treated groups and the (mock) control are indicated: *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01.

4. Discussion

RNAi is a widely employed approach in reverse genetics for specific knockdown of target genes. The RNAi mechanism is conserved among eukaryotes, including schistosomes (see Krautz-Peterson et al., 2010). RNAi is triggered by dsRNA and results in inactivation of the target gene through degradation of homologous mRNAs and/or inhibition of mRNA translation. In the context of vector-based RNAi, the molecular biology of RNAi has been reviewed (e.g., Cheng and Chang, 2007; Sliva and Schnierle, 2010). In brief, episomal or integrated transgenes, comprising pol III promoters driving target sequence-specific cassettes, lead to over-expression of shRNAs, of ~21 nt of stem (range 19–29 nt) and ~ 9 nt (range 4–23) of loop sequences (Brummelkamp et al., 2002; Miyagishi and Taira, 2002; Paddison et al., 2002). After export from the nucleus the shRNA is cleaved by Dicer and enters the RNA-induced silencing complex, which unwinds the RNA and targets the specific mRNA for degradation. Vector-based RNAi provides advantages over the direct introduction of siRNA or dsRNA to target cells, including long-term and/or conditional gene silencing. It also can be cost effective, given that synthesis of siRNA is expensive, its effect transient and in addition, long dsRNA can induce a cytotoxic response in mammalian cells (Williams, 1999). On the other hand, the RNAi effect using a vector-based system is more stable due to sustained production of shRNA.

We isolated 270 bp of genomic DNA flanking the S. mansoni U6 small nRNA gene, a component of the spliceosome machinery (see Copeland et al., 2009), and constructed a RNAi expression cassette using this putative promoter to drive expression of shRNAs specific for firefly luciferase. We observed significant knockdown of luciferase in human fibrosarcoma cells and in schistosomules transfected with the expression cassette. The findings demonstrated that the S. mansoni U6 gene promoter drove shRNA expression that induced RNAi in a human cell and in schistosomules. In addition to schistosome and human U6 gene promoters, orthologous U6 promoters from pathogenic amebae, Drosophila, sea squirts, fugu fish, chicken and bovines also function in Pol III driven vector-based RNAi expression systems (Lambeth et al., 2005; Wakiyama et al., 2005; Wise et al., 2007; Nishiyama and Fujiwara, 2008; Zenke and Kim, 2008; Linford et al., 2009).

Although this S. mansoni U6 gene promoter is active in schistosomes and in HT1080 cells, the knockdown experiments performed in HT1080 cells were more consistent and reproducible than those with schistosomules. However, even in HT1080 cells we did not observe a concentration effect; 10 µg did not induce significantly greater silencing than 4 µg of pXL-BacII_SmU6 shLuc. This may reflect saturation of the cellular microRNA/shRNA pathway leading to competition for limited cellular factors such as nuclear karyopherin exportin-5 (see Grimm et al., 2006; Snøve and Rossi, 2006). The non-specific reduction of luciferase activity in schistosomules detected in the control shRNA group may reflect dysfunction of the mRNA translation machinery. Schistosomules clearly are less tractable for these approaches than mammalian cell lines but since functional genomics tools are needed for schistosomes, and because cell lines are not available for schistosomes, we have targeted larval schistosomes here to investigate a prospective new approach (Mann et al., 2008, 2010). Cultured HT1080 cells not only have a larger surface area, but here were transfected only once with the vector short hairpin plasmid whereas the schistosomules were transfected with this plasmid and, secondly, with the mRNA encoding luciferase. Exposing worms twice to electroporation may be deleterious and reflected in inconsistent outcomes in the replicates. Moreover, knockdown of luciferase in these particular HT1080 cells represented silencing of an ‘endogenous’ gene since the cells expressed firefly luciferase from integrated lentiviral transgenes. Perhaps most critical was that since schistosomules are multicellular, some but not all of the cells were transformed with both pXL-BacII_SmU6-shLuc and luciferase mRNA. Cells of the digestive tract and/or tegument are likely transduced by the plasmid and/or the mRNA, whereas more internal cells may not have been transfected. Nonetheless, we can predict that after entry into the schistosome cell, the episome was transcribed and processed, and the siRNAs transmitted to adjacent cells by transporters such as Sid 1 (Krautz-Peterson and Skelly, 2008). In this regard and to improve assay reproducibility, increasing the time between the plasmid and the luciferase mRNA transfection might be beneficial so that siRNAs might spread from the transfected cells, leading to enhanced knockdown.

Recently, proof-of-principle for vector-based RNAi was demonstrated in S. mansoni, using a MLV (retrovirus) vector (Tchoubrieva et al., 2010). However, those investigators used a RNA polymerase II dependent promoter and a long hairpin of ~120 bp targeting a protease involved in hemoglobinolysis. Whereas this retroviral vector-based RNAi system is functional, there may be advantages to deploying a Pol III dependent promoter: the U6 promoter is known to competently and continuously transcribe small RNAs, is highly active in all or most cells and tissues, and its diminutive size fits within the limits on cargo size of the expression cassette (Paddison et al., 2002; Scherr and Eder, 2007). The significance of both findings with vector-based RNAi in schistosomes, the present findings and those of Tchoubrieva et al. (2010) is that vector-based RNAi should allow targeting of any schistosome gene for continuous knockdown and subsequent examination of the importance of the targeted gene. Moreover, plasmid pXL-BacII, from which we constructed pXL-BacII_SmU6-shLuc, contains the inverted terminal repeats of transposon piggyBac (Li et al., 2005). Given that piggyBac is transpositionally active in S. mansoni (Morales et al., 2007), pXL-BacII_SmU6-shLuc could be utilized to generate transgenic schistosomes, that inherit trans-generational silencing of report luciferase, by co-transfecting schistosomes with this shRNA inducing plasmid along with the piggyback transposase.

High throughput RNAi analysis will advance functional genomics for schistosomes, and indeed parasitic helminths at large. We anticipate that the information presented here describing the schistosome U6 promoter and its activity in vector-based RNAi will contribute to establishment of these analyses. We are interested to establish long-term, stable and trans-generational RNAi to aid discovery of essential schistosome genes which could, in turn, be targeted in new approaches for treatment and control of schistosomiasis.

Acknowledgements

Schistosome-infected snails were supplied by Dr. Fred Lewis (Biomedical Research Institute, Rockville, MD USA) under National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) contract HHSN272201000005I. These studies were supported by NIH-NIAID award R01AI072773 (the content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIAID or the NIH).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Basch PF. Cultivation of Schistosoma mansoni in vitro. I. establishment of cultures from cercariae and development until pairing. J. Parasitol. 1981;67:179–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann S, Wippersteg V, El-Bahay A, Hirzmann J, Oliveira G, Grevelding CG. Schistosoma mansoni: Germ-line transformation approaches and actin-promoter analysis. Exp. Parasitol. 2007;117:292–303. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berriman M, Haas BJ, LoVerde PT, Wilson RA, Dillon GP, Cerqueira GC, Mashiyama ST, Al-Lazikani B, Andrade LF, Ashton PD, Aslett MA, Bartholomeu DC, Blandin G, Caffrey CR, Coghlan A, Coulson R, Day TA, Delcher A, DeMarco R, Djikeng A, Eyre T, Gamble JA, Ghedin E, Gu Y, Hertz-Fowler C, Hirai H, Hirai Y, Houston R, Ivens A, Johnston DA, Lacerda D, Macedo CD, McVeigh P, Ning Z, Oliveira G, Overington JP, Parkhill J, Pertea M, Pierce RJ, Protasio AV, Quail MA, Rajandream MA, Rogers J, Sajid M, Salzberg SL, Stanke M, Tivey AR, White O, Williams DL, Wortman J, Wu W, Zamanian M, Zerlotini A, Fraser-Liggett CM, Barrell BG, El-Sayed NM. The genome of the blood fluke Schistosoma mansoni. Nature. 2009;460:352–358. doi: 10.1038/nature08160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brindley PJ, Mitreva M, Ghedin E, Lustigman S. Helminth genomics: The implications for human health. PLoS Negl Trop. Dis. 2009;3:e538. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brindley PJ, Pearce EJ. Genetic manipulation of schistosomes. Int. J. Parasitol. 2007;37:465–473. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2006.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brummelkamp TR, Bernards R, Agami R. A system for stable expression of short interfering RNAs in mammalian cells. Science. 2002;296:550–553. doi: 10.1126/science.1068999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng TL, Chang WT. Construction of simple and efficient DNA vector-based short hairpin RNA expression systems for specific gene silencing in mammalian cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 2007;408:223–241. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-547-3_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland CC, Marz M, Rose D, Hertel J, Brindley PJ, Bermudez-Santana C, Kehr S, Stephan-Otto Attolini C, Stadler PF. Homology-based annotation of non-coding RNAs in the genomes of Schistosoma mansoni and Schistosoma japonicum. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:464. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correnti JM, Pearce EJ. Transgene expression in Schistosoma mansoni: Introduction of RNA into schistosomula by electroporation. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2004;137:75–79. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlberg JE, Schenborn ET. The human U1 snRNA promoter and enhancer do not direct synthesis of messenger RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:5827–5840. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.13.5827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gou D, Jin N, Liu L. Gene silencing in mammalian cells by PCR-based short hairpin RNA. FEBS Lett. 2003;548:113–118. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00630-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm D, Streetz KL, Jopling CL, Storm TA, Pandey K, Davis CR, Marion P, Salazar F, Kay MA. Fatality in mice due to oversaturation of cellular microRNA/short hairpin RNA pathways. Nature. 2006;441:537–541. doi: 10.1038/nature04791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu J, Reddy R. Compilation of small RNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:3481–3482. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.17.3481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall TA. BioEdit: A user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for windows 95/98/NT. Nucl. Acids. Symp. Ser. 1999;41:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Kines KJ, Mann VH, Morales ME, Shelby BD, Kalinna BH, Gobert GN, Chirgwin SR, Brindley PJ. Transduction of Schistosoma mansoni by vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein-pseudotyped Moloney murine leukemia retrovirus. Exp. Parasitol. 2006;112:209–220. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kines KJ, Morales ME, Mann VH, Gobert GN, Brindley PJ. Integration of reporter transgenes into Schistosoma mansoni chromosomes mediated by pseudotyped murine leukemia virus. FASEB J. 2008;22:2936–2948. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-108308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kines KJ, Rinaldi G, Okatcha TI, Morales ME, Mann VH, Tort JF, Brindley PJ. Electroporation facilitates introduction of reporter transgenes and virions into schistosome eggs. PLoS Negl Trop. Dis. 2010;4:e593. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krautz-Peterson G, Bhardwaj R, Faghiri Z, Tararam CA, Skelly PJ. RNA interference in schistosomes: Machinery and methodology. Parasitology. 2010;137:485–495. doi: 10.1017/S0031182009991168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krautz-Peterson G, Skelly PJ. Schistosoma mansoni: The dicer gene and its expression. Exp. Parasitol. 2008;118:122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambeth LS, Moore RJ, Muralitharan M, Dalrymple BP, McWilliam S, Doran TJ. Characterisation and application of a bovine U6 promoter for expression of short hairpin RNAs. BMC Biotechnol. 2005;5:13. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazdins JK, Stein MJ, David JR, Sher A. Schistosoma mansoni: Rapid isolation and purification of schistosomula of different developmental stages by centrifugation on discontinuous density gradients of percoll. Exp. Parasitol. 1982;53:39–44. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(82)90090-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Harrell RA, Handler AM, Beam T, Hennessy K, Fraser MJ., Jr piggyBac internal sequences are necessary for efficient transformation of target genomes. Insect Mol. Biol. 2005;14:17–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2004.00525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linford AS, Moreno H, Good KR, Zhang H, Singh U, Petri WA., Jr Short hairpin RNA-mediated knockdown of protein expression in Entamoeba histolytica. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:38. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann VH, Morales ME, Kines KJ, Brindley PJ. Transgenesis of schistosomes: Approaches employing mobile genetic elements. Parasitology. 2008;135:141–153. doi: 10.1017/S0031182007003824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann VH, Morales ME, Rinaldi G, Brindley PJ. Culture for genetic manipulation of developmental stages of Schistosoma mansoni. Parasitology. 2010;137:451–462. doi: 10.1017/S0031182009991211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyagishi M, Taira K. Development and application of siRNA expression vector. Nucleic Acids Res. Suppl. 2002;(2):113–114. doi: 10.1093/nass/2.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales ME, Mann VH, Kines KJ, Gobert GN, Fraser MJ, Jr, Kalinna BH, Correnti JM, Pearce EJ, Brindley PJ. piggyBac transposon mediated transgenesis of the human blood fluke, Schistosoma mansoni. FASEB J. 2007;21:3479–3489. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8726com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama A, Fujiwara S. RNA interference by expressing short hairpin RNA in the Ciona intestinalis embryo. Dev. Growth Differ. 2008;50:521–529. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2008.01039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paddison PJ, Caudy AA, Bernstein E, Hannon GJ, Conklin DS. Short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) induce sequence-specific silencing in mammalian cells. Genes Dev. 2002;16:948–958. doi: 10.1101/gad.981002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldi G, Morales ME, Cancela M, Castillo E, Brindley PJ, Tort JF. Development of functional genomic tools in trematodes: RNA interference and luciferase reporter gene activity in fasciola hepatica. PLoS Negl Trop. Dis. 2008;2:e260. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaub M, Myslinski E, Krol A, Carbon P. Maximization of selenocysteine tRNA and U6 small nuclear RNA transcriptional activation achieved by flexible utilization of a staf zinc finger. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:25042–25050. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.35.25042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherr M, Eder M. Gene silencing by small regulatory RNAs in mammalian cells. Cell. Cycle. 2007;6:444–449. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.4.3807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schistosoma japonicum Genome Sequencing and Functional Analysis Consortium. The Schistosoma japonicum genome reveals features of host-parasite interplay. Nature. 2009;460:345–351. doi: 10.1038/nature08140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sliva K, Schnierle BS. Selective gene silencing by viral delivery of short hairpin RNA. Virol. J. 2010;7:248. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-7-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snøve O, Jr, Rossi JJ. Toxicity in mice expressing short hairpin RNAs gives new insight into RNAi. Genome Biol. 2006;7:231. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-8-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanic S, Dvorak J, Horn M, Braschi S, Sojka D, Ruelas DS, Suzuki B, Lim KC, Hopkins SD, McKerrow JH, Caffrey CR. RNA interference in Schistosoma mansoni schistosomula: Selectivity, sensitivity and operation for larger-scale screening. PLoS Negl Trop. Dis. 2010;4:e850. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm RA, Das G, Herr W. The ubiquitous octamer-binding protein oct-1 contains a POU domain with a homeo box subdomain. Genes Dev. 1988;2:1582–1599. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.12a.1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tchoubrieva EB, Ong PC, Pike RN, Brindley PJ, Kalinna BH. Vector-based RNA interference of cathepsin B1 in Schistosoma mansoni. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2010;67:3739–3748. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0345-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ter Brake O, Konstantinova P, Ceylan M, Berkhout B. Silencing of HIV-1 with RNA interference: A multiple shRNA approach. Mol. Ther. 2006;14:883–892. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakiyama M, Matsumoto T, Yokoyama S. Drosophila U6 promoter-driven short hairpin RNAs effectively induce RNA interference in Schneider 2 cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;331:1163–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams BR. PKR; a sentinel kinase for cellular stress. Oncogene. 1999;18:6112–6120. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise TG, Schafer DJ, Lambeth LS, Tyack SG, Bruce MP, Moore RJ, Doran TJ. Characterization and comparison of chicken U6 promoters for the expression of short hairpin RNAs. Anim. Biotechnol. 2007;18:153–162. doi: 10.1080/10495390600867515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Brindley PJ, Zeng Q, Li Y, Zhou J, Liu Y, Liu B, Cai L, Zeng T, Wei Q, Lan L, McManus DP. Transduction of Schistosoma japonicum schistosomules with vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein pseudotyped murine leukemia retrovirus and expression of reporter human telomerase reverse transcriptase in the transgenic schistosomes. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2010;174:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenke K, Kim KH. Novel fugu U6 promoter driven shRNA expression vector for efficient vector based RNAi in fish cell lines. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008;371:480–483. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.04.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]