Abstract

We have generated effector T cells from tumor-draining lymph nodes that are efficacious in adoptive immunotherapy. We now examined the effect of concomitant tumors on the generation of effector T cells. We inoculated MCA 205 in the flanks of normal mice and mice bearing MCA 205 lung metastases. Tumor-draining lymph node cells from these mice were activated and expanded in vitro, and adoptively transferred to mice bearing lung metastases. Effector T cells (TDLN) generated from tumor-draining lymph nodes in mice with only flank tumor mediated potent antitumor activity. However, antitumor efficacy of the effector T cells generated from tumor-draining lymph nodes in mice with pre-existent lung tumor (cTDLN) was reduced. Phenotyping studies showed that dendritic cells in cTDLN expressed higher levels of B7-H1; while cTDLN T cells expressed higher levels of PD-1. The levels of IFNγ were reduced, and the levels of CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells were increased from cTDLN vs. TDLN. The in vitro activation of cTDLN was increased by blocking B7-H1 or TGF-β. Importantly, we found a synergistic upregulation of IFNγ with simultaneous blockade of B7-H1 and TGF-β that was much greater than observed with TDLN. In vitro activation of cTDLN with anti-B7-H1 and anti-TGF-β and in vivo administration of these antibodies after adoptive transfer resulted in the abrogation of the suppression associated with cTDLN. These results demonstrate a major role of the B7-H1/PD-1 axis and TGF-β as synergistic suppressive mechanisms in cTDLN. Our data has clinical relevance in the generation of effector T cells in the tumor-bearing host.

Keywords: Adoptive immunotherapy, B7-H1, TGF-β, PD-1, Tregs

Introduction

The clinical application of adoptive cellular immunotherapy has relied upon the generation of tumor-reactive effector cells derived from the patient bearing cancer. This requires the ability to isolate and expand tumor-reactive cells. One of the successful methods has been to isolate effector T cells from a growing tumor, namely tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) and expand them in medium containing IL-21–3. However, the successful generation of TIL is not always reliable nor are they always effective after adoptive transfer4. Our laboratory has been interested in developing effector T cells from lymph nodes primed by tumor antigen administered as a vaccine5, 6. Pre-effector lymph node cells are primed in vivo, and subsequently activated and expanded in vitro by methods we have described previously7, 8. In animal models and in clinical studies, these vaccine-primed lymph node cells can mediate the regression of established tumors9–12. However, in clinical trials, only a subgroup of patients benefits. Clearly there is a need to further improve these therapies which can result in durable remissions.

The original animal models we have established upon which we have predicated our clinical studies, have utilized non-tumor bearing mice as donors for tumor-primed lymph node cells. However, as noted above, this does not mirror the clinical setting where patients bearing tumors need to be the donors for effector cells that can be used for adoptive immunotherapy. To accurately mimic the clinical setting, we have established tumor-bearing models where in vivo tumor priming is performed to elicit pre-effector lymph node cells. Not surprisingly, we have demonstrated that the tumor-bearing host is not a favorable environment to induce pre-effector cells compared to normal non-tumor-bearing hosts. In this study we have identified mechanisms by which this tumor-induced immune suppression occurs and some approaches to abrogate this suppression. Our findings have relevance not only to adoptive cell therapies, but also to active immunotherapies involving vaccinations.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Female C57BL/6 (B6, Thy1.2) and B6.PL-Thy1a/CyJ (Thy1.1) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). All the mice were maintained in specific pathogen-free conditions and were used for experiments at 8 weeks of age or older. Recognized principles of laboratory animals care (NIH publication No. 85-23, revised 1985) were followed, and the University of Michigan Laboratory of Animal Medicine approved all animal protocols.

Murine tumor cells

MCA 205 is a 3-methylcholanthrene-induced weakly immunogenic fibrosarcoma that is syngeneic to B6 mice. Tumors were maintained in vivo by serial subcutaneous (s.c.) transplantation in B6 mice and were used within the eighth transplantation generation. Tumor cell suspensions were prepared from solid tumors by enzymatic digestion in 50 ml of Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY) containing 40 mg of collagenase, 4 mg of deoxyribonuclease I and 100 units of hyaluronidase (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) for 2 hours at room temperature. Tumor cells were washed in HBSS 3 times before s.c. injection in mice to induce TDLN. MC38, a colon cancer tumor syngeneic to B6 mice was used as a specificity control.

Concomitant tumor model

To elicit TDLN, normal B6 mice were inoculated with 1 × 106 MCA 205 tumor cells in 0.2ml of phosphate buffered saline (PBS) s.c. in the lower flank. In the concomitant tumor model, B6 mice were given 0.2 × 106 tumor cells by tail vein injection to establish pulmonary metastasis. Three to 6 days later, these mice were given 1 × 106 tumor cells s.c. in the lower flank.

Lymph node (LN) preparation

Nine days after flank tumor inoculation, inguinal lymph nodes from mice bearing only flank tumor (TDLN) or mice bearing both flank tumor and lung metastasis (cTDLN) were removed aseptically. Multiple TDLN or cTDLN were pooled from groups of mice. Lymphoid cell suspensions were prepared by mechanical disruption with the blunt end of a 3-mL plastic syringe in HBSS. The resultant cell suspension was filtered through 40µm cell strainer and washed in HBSS.

Activation of TDLN cells

TDLN cells were activated with 1.0 µg/ml anti-CD3 mAb plus 1.0 µg/ml anti-CD28 mAb (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) immobilized in 6-well plates (20 × 106 cells/10ml/well) at 37°C with 5% CO2 for two days. For antibody immobilization, each well of a 6-well cell culture plate (Costar, Cambridge, MA) was coated with 4 ml of anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 at 4° C overnight or at room temperature for 5 to 6 hours. After antibody activation, the cells were harvested and counted. The cells were then expanded in complete media (CM) containing human recombinant IL-2 (Chiron Therapeutics, Emeryville, CA) starting at a concentration of 3 × 105 cells per ml in tissue culture flasks (Costar) for three days. CM consisted of RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 0.1mM nonessential amino acids, 1mM sodium pyruvate, 2mM fresh L-glutamine, 100mg/ml streptomycin, 100 units/ml penicillin, 50ug/ml gentamicin, 0.5ug/ml Fungizone (all from Life Technologies, Inc.) and 0.05mM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma). The concentration of IL-2 was 80 international units (IU)/ml. At the end of the cell expansion, cells were harvested and counted to determine the fold of expansion and were used for adoptive transfer. The supernatant was collected. IFN-γ was detected with BD OptEIA mouse IFN-γ ELISA set (BD PharMingen).

Treatment of established pulmonary metastases

Pulmonary metastases were established via tail vein injection of viable MCA 205 cells (2 × 105) in B6 mice. Three day tumor-bearing mice were infused intravenously (i.v.) with TDLN cells activated with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 and expanded in IL-2. Commencing on the day of the cell transfer (day 0), intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of IL-2 (40,000 IU) were administered in 0.5 ml of PBS and continued twice daily for eight doses. Approximately 14 days after tumor injection, all mice were sacrificed, and lungs were harvested for enumeration of pulmonary metastatic nodules. The metastases appeared as discrete white nodules on the black surface of lungs insufflated with a 15% solution of India ink.

Fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis

All antibodies for flow cytometry were purchased from BD PharMingen (San Jose, CA) except antibodies for Foxp3 and granzyme B which were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Foxp3 staining was performed using a commercial kit (eBioscience) according to the manufacturer’s directions. Flow cytometry was performed on a LSRII (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA) and data were analyzed using Diva software (BD Bioscience).

T cell intracellular cytokine profile analysis

T cells were stimulated for 4 hours with leukocyte activation cocktail (ready-to-use polyclonal cell activation mixture with phorbol ester Phorbol 12-Myristate 13-Acetate, a calcium ionophore (Ionomycin), and the protein transport inhibitor BD GolgiPlug™ (brefeldin A), BD PharMingen). Cells were first stained extracellularly with anti-CD4, anti-CD8 and anti-CD90, then were fixed and permeabilized with Fixation/Permeabilization solution (eBioscience), and finally were stained intracellularly with antibodies to mouse IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, perforin, granzyme B and IFN-γ (BD PharMingen). Samples were acquired on a LSR II and data were analyzed with DIVA software.

ELISPOT assay

MultiScreen filtration plates (96-wells/plate; Millipore, Bedfored, MA) were coated with 100 µl/well of 4 µg/ml purified anti-mouse IFNγ monoclonal antibody (clone R4-6A2; BD PharMingen) overnight at 4°C and then incubated for 90 min at room temperature with 150 µl/well 1% BSA (Sigma) in PBS. Activated lymphocytes (2 × 105 cells in 100 µl of CM) were placed into each well and and incubated for 24 h at 37°C, 5% CO2 in the absence of presence of irradiated (60 Gy) specific MCA 205 tumor cells or irrelevant mouse MC38 tumor cells (5 × 104 cells in 100 µl of CM). Plates were incubated overnight at 4°C with 100 µl/well of 4 µl/ml of biotinylated rat anti-mouse IFNγ monoclonal antibody (clone XMG1.2; BD PharMingen) followed by a 90-min incubation with 100 µl/well anti-biotin alkaline phosphatase (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA) diluted 1:1000. Spots were visualized with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate/nitroblue tetrazolium alkaline phosphatase substrate and counted using the ImmunoSpot analyzer (Cellular Technology, Ltd., Cleveland, OH). Data are reported as an average number of spots per 2 × 105 responders ± SE of triplicate samples.

Blockade of B7-H1 and TGF-β

Anti-mouse B7-H1 mAb (clone MIH5; rat IgG2a, λ isotype, eBioscience) 5ng/ml and anti-TGF-β 1/300 (ascites raised with hybridoma B lymphocyte 1D11.16.8 purchased from American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) was added to the TDLN and cTDLN cells during activation with anti-CD3/CD28 and during expansion with IL-2 in order to block B7-H1 and TGF-β in vitro. Anti-mouse B7-H1 mAb (clone 10B5, hamster IgG)13, was used to block the B7-H1 for the in vivo experiments. This larger quantity of mAb was provided by Dr. L Chen. 50 µg anti-B7-H1 and 100 ul of anti-TGF-β was given i.p. on the day of adoptive transfer and on day 3, 6, 9 after adoptive transfer.

In order to determine if the in vivo blockade of B7-H1 and TGF-β was affecting the transferred cTDLN or had an effect on host immune cells, expanded cTDLN cells from Thy1.2 C57BL/6 mice were transferred to 3-day lung metastasis bearing Thy1.1 mice. Lungs were harvested 8 days after adoptive transfer. Single cell suspension from lungs were first stained extracellularly for CD45, CD90.1, CD90.2, CD4 and CD8 and then stained for intracellular IFN-γ and Foxp3 as described above. Donor T cells were gated on CD45+CD90.2+ and recipient T cells were gated on CD45+CD90.1+.

Statistical analysis

In the adoptive transfer model, the significance of differences in numbers of metastatic nodules between experimental groups was determined by the one-way ANOVA test using StatView software. P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant Student’s t-test was used to analyze flow cytometry and cytokine release data. Two-tailed p values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant between two groups.

Results

Pre-established visceral or subcutaneous tumor will suppress the induction of TDLN effector T cells

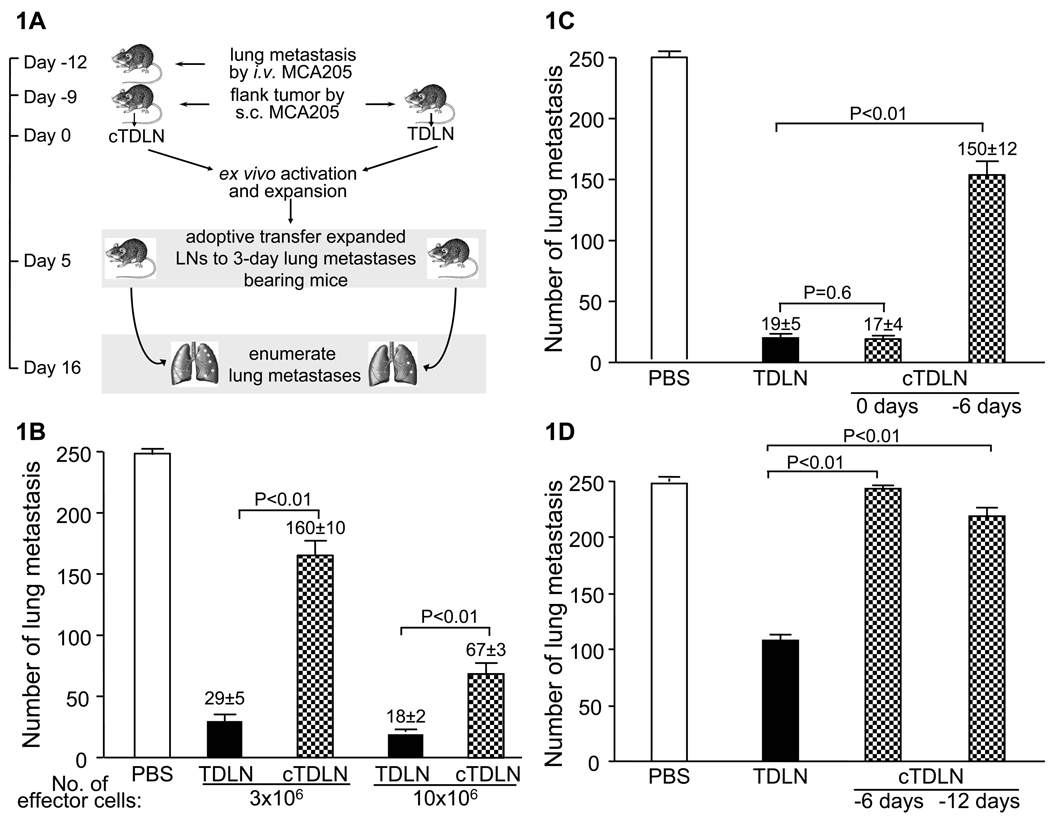

We utilized the MCA 205 sarcoma tumor model to evaluate the effect of pre-existent tumor on the ability to elicit TDLN cells for adoptive immunotherapy. Groups of mice were inoculated with tumor cells i.v. to establish lung metastases 3 to 6 days before s.c. inoculation of tumor cells in the flank as described in the Methods section (Fig. 1A). Control mice received s.c. tumor, but not i.v. tumor cells. Nine days after s.c. inoculation of tumor cells, TDLN were harvested from the inguinal regions. The effector T cells generated from mice receiving s.c tumor were termed TDLN (TDLN). The effector T cells generated from mice receiving i.v. and s.c tumor were termed concomitant TDLN (cTDLN). The tumor draining lymph node cells were activated in anti-CD3/CD28 as described in the Methods section and expanded in IL-2. After the culture period, the antitumor reactivity of the cells was assessed in the adoptive immunotherapy of 3-day established lung metastases as described in the Methods section. As illustrated in Fig. 1B, the antitumor reactivity of the cTDLN was significantly reduced on a per cell basis compared to equivalent numbers of transferred TDLN in a dose dependent manner. The data suggest that concomitant visceral tumor induces immune suppression in the tumor draining lymph nodes. In a separate experiment, we found that the reduced effector function of cTDLN was dependent upon timing of the lung tumor establishment. If i.v. tumor cells were injected the same day as s.c. tumor inoculation, the effector function remained, suggesting that there was no significant immune suppression induced by the lung tumors (Fig. 1C). It indicates that the lung tumors needed to be established prior to s.c. tumor inoculation.

Figure 1.

Pre-established visceral or subcutaneous tumor suppressed the induction of TDLN effector T cells. A. Concomitant tumor model and schematic experimental design. TDLN were harvested from the inguinal regions of mice bearing 9-day flank tumor by s.c. inoculation. cTDLN were harvested from the inguinal regions of mice given tumor cells by i.v. inoculation 3 days prior to the s.c. inoculation of tumor cells in the flank. TDLN and cTDLN cells were activated and expanded ex vivo and then adoptively transferred to mice with pulmonary metastases. B. The antitumor activity of the cTDLN was significantly reduced compared to comparable numbers of TDLN cells as assessed by the enumeration of pulmonary metastatic nodules. C. The reduced antitumor activity of the cTDLN was dependent on the establishment of the lung tumor prior (ie. 6 days) to s.c. tumor inoculation as opposed to the same day (ie. day 0). 2 × 106 cells were transferred. D. The establishment of s.c. flank tumors 6 and 12 days prior to inoculating tumor cells in the contralateral flank resulted in cTDLN with reduced antitumor reactivity compared to TDLN cells as assessed in the adoptive immunotherapy model. 5 × 106 cells were transferred. Two independent experiments with 5 animals per experiment per group.

We proceeded to determine if pre-existent subcutaneous tumor, as opposed to visceral tumor, would suppress the in vivo priming of effector cells. In this experiment, MCA 205 tumor was inoculated s.c. in the flank 6 and 12 days before injecting tumor cells in the contralateral flank. Control mice were inoculated with tumor cells on one flank only. TDLN and cTDLN were harvested 9 days after the last flank injection. As before, the cells were activated and expanded and their antitumor reactivity assessed in the adoptive immunotherapy model. As shown in Fig. 1D, pre-existent s.c. flank tumors had an adverse effect in the priming of effector cells in the LNs.

Phenotypic differences between TDLN and cTDLN: dendritic cells, Tregs, and T effector cells

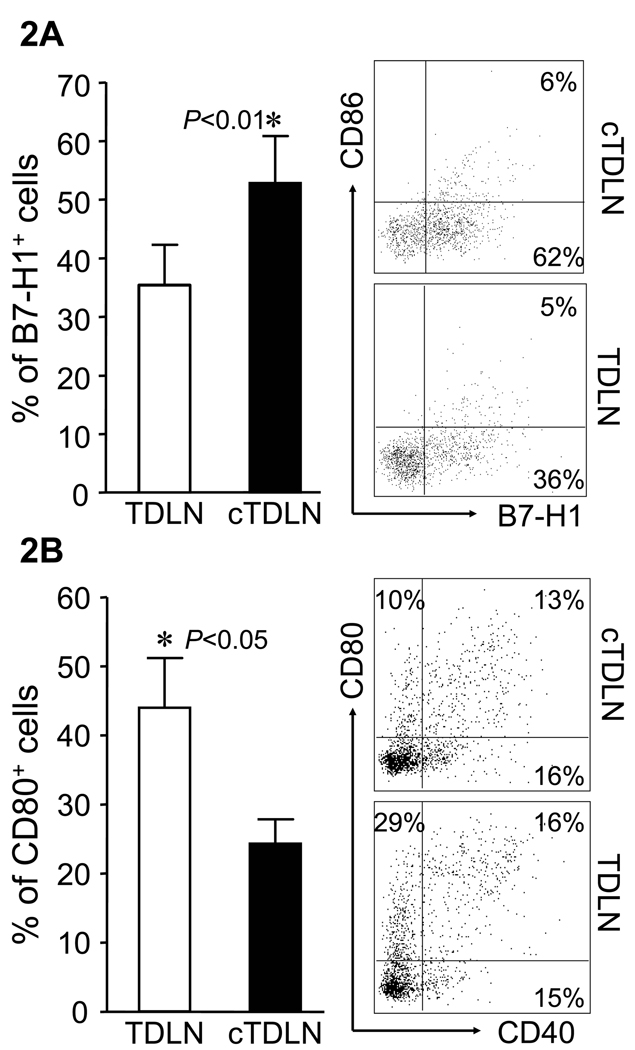

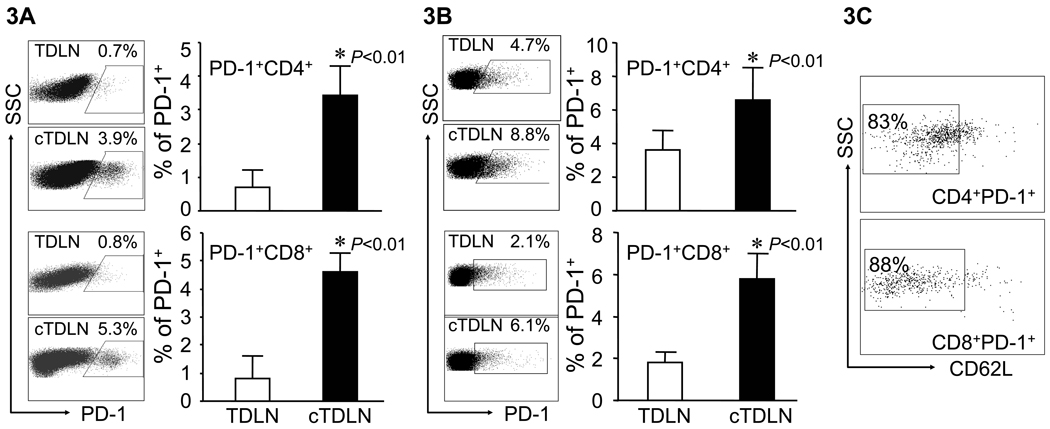

We proceeded to examine differences in the LN cellular subsets between TDLN and cTDLN. The latter were established utilizing mice with 12-day lung metastases and 9-day flank tumors to prime draining LNs. TDLN were harvested from control mice that had 9-day flank tumors. TDLN and cTDLN were obtained from several mice and separately pooled. The number of cells obtained per TDLN vs. cTDLN were not significantly different (data not shown). The first cell subset we examined were DC (CD11b−CD11c+) with respect to various co-stimulatory and co-inhibitory markers. There were no differences in the expression of CD40, CD86 or MHC class II between DC from both groups. However, we did observe significant up-regulation of B7-H1 (Fig. 2A) with a concomitant down-regulation of CD80 (Fig. 2B) in DC from cTDLN compared to TDLN. This represents an alteration in host DC induced by the presence of established tumor that has not been previously described. Because of this finding, we examined the expression of the ligand for B7-H1, namely PD-1, on TDLN and cTDLN T cells. In Fig. 3A, we found that PD-1 was significantly more expressed on activated CD4+ and CD8+ cells from cTDLN compared to TDLN. This up-regulated expression of PD-1 in cTDLN cells was maintained after expansion in IL-2 for 3 days (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, the PD-1+ T cells in cTDLN expressed low levels of L-selectin (CD62L) (Fig. 3C). We examined expression of OX-40 and CTLA-4 on fresh and activated LN cells and did not find significant differences between the two groups (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Altered expression of B7 family members in cTDLN. A. Higher levels of B7-H1 on cTDLN DC compared to TDLN DC. B. Lower levels of CD80 in DCs were observed in freshly harvested cTDLN compared to TDLN. The expression of B7-H1 and CD80 was determined by FACS analysis, gated on lin−CD11c+CD11b− cells. Data were expressed as the mean percent of expression ± SEM. Results are from at least 3 independent experiments with 4 mice per group. In each experiment lymph nodes were pooled from each individual mouse and analyzed separately.

Figure 3.

Altered expression of PD-1 expression observed on T cells from cTDLN compared to TDLN. A. Freshly harvested T cells from cTDLN was increased compared to TDLN. B. After activation and expansion in culture this increased expression of PD-1 by cTDLN cells compared to TDLN cells was still observed. The expression of PD-1 was determined by FACS analysis, gated on CD4+CD90+ or CD8+CD90+ T cells. C. Majority of the PD-1+ T cells observed in expanded cTDLN expressed low levels of L-selectin. Data were expressed as the mean percent of expression ± SEM. Results are from at least 3 independent experiments with 4 mice per group. In each experiment lymph nodes were pooled from each individual mouse and analyzed separately.

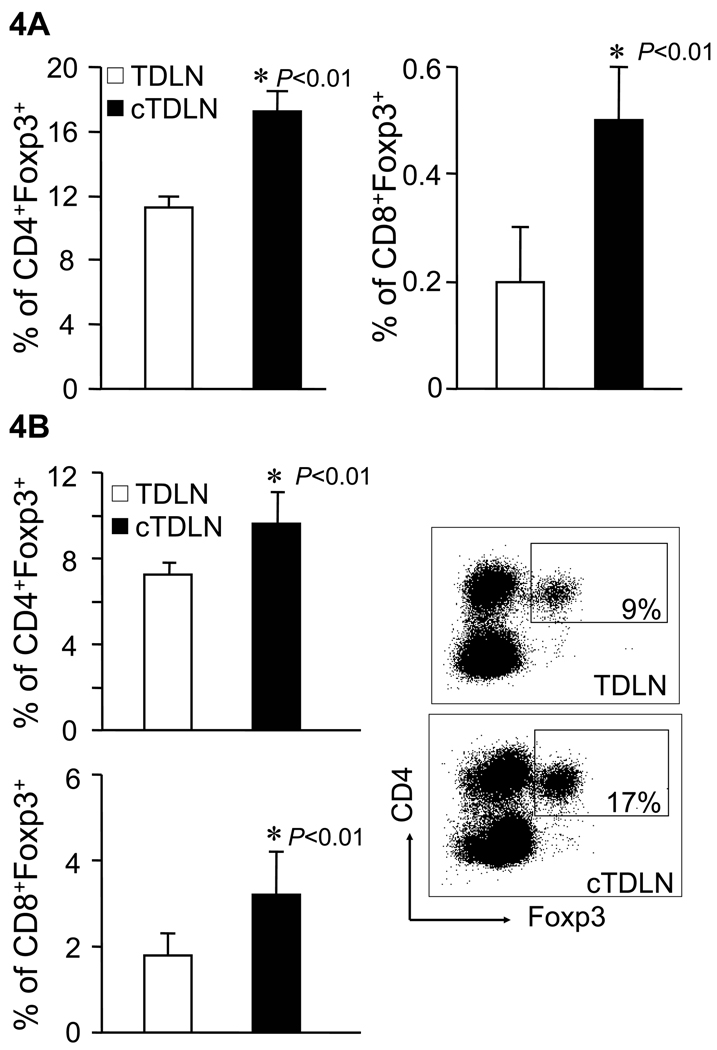

We also looked at T cell subpopulations from freshly harvested cTDLN vs. TDLN. There were no significant differences in the percentage of CD3+, CD4+, or CD8+ lymphoid cells. However, we did observe an increased percentage of CD4+Foxp3+ cells obtained from cTDLN compared with TDLN (Fig. 4A). In addition, there was an increased percentage of CD8+Foxp3+ found in cTDLN compared to TDLN (Fig. 4A). After antibody activation and expansion in IL-2, the CD4+Foxp3+ and CD8+Foxp3+ subpopulations persisted (Fig. 4B)

Figure 4.

Increased Foxp3+CD4+ and Foxp3+CD8+ T cells were observed in cTDLN compared with TDLN. Increased Foxp3+CD4+ and Foxp3+CD8+ T cells were observed in freshly harvested (A) and activated/expanded (B) cTDLN compared to TDLN. The percent of Foxp3+ T cells was determined by FACS analysis, gated on CD4+CD90+ or CD8+CD90+ T cells. Results were expressed as the mean percent of Foxp3+ T cells ± SEM. Results are from at least 3 independent experiments with 4 mice per group. In each experiment lymph nodes were pooled from each individual mouse and analyzed separately.

Functional differences between TDLN and cTDLN cells

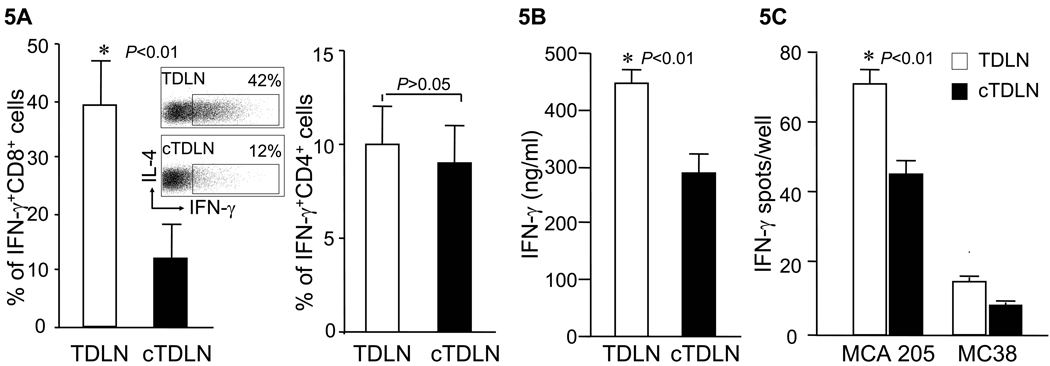

We proceeded to evaluate the functional characteristics of T cells obtained from cTDLN compared with TDLN. Intracytoplasmic staining for IFNγ revealed decreased levels in cTDLN compared with TDLN (Fig. 5A; p<0.01). This was correlated with decreased amounts of IFNγ production by cTDLN effector cells compared with TDLN cells during activation and expansion of cells as described in the Methods section (Fig. 5B; p<0.01)). We further analyzed the response of these activated cells in response to irradiated tumor utilizing an ELISPOT assay (Fig. 5C), and show that the number of tumor-induced IFNγ spots were significantly reduced in cTDLN compared with TDLN (p<0.01). This was a tumor specific response as demonstrated by the low number of spots in response to MC38 tumor cells. We also evaluated intracytoplasmic staining of IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, perforin and granzyme B. We did not detect IL-4 or IL-10 intracytoplasmically. There were low levels of intracytoplasmic IL-2 that were similar between both groups of LN cells. Almost all the cells in both groups expressed perforin and granzyme B at similar levels (data not shown).

Figure 5.

cTDLN cells produced less IFNγ compared to TDLN cells. A. Percent of IFNγ+CD8+ cells was lower in activated/expanded cTDLN compared to TDLN, while the percent of IFNγ+CD4+ cells was similar in TDLN and cTDLN. The percent of IFNγ+ T cells was determined by intracellular staining and analyzed by FACS analysis, gated on CD8+CD90+ and CD4+CD90+ T cells. Results were expressed as the mean percent of IFNγ+ T cells ± SEM (8 independent experiments). B. The secretion of IFNγ was lower in expanded cTDLN compared to TDLN. Supernatants were collected from the expanded cTDLN and TDLN cells. IFNγ was detected by ELISA. Results were expressed as the mean values of IFNγ ± SEM of triplicate samples from 3 independent experiments. C. The frequency of tumor specific IFNγ-producing effector cells was significantly less in the cTDLN population. 2×105 effector cells were cultured alone or in the presence of 5×104 irradiated specific MCA 205 or irrelevant mouse MC38 tumor cells for 24hr in 96-well ELISPOT plates coated with anti-IFN-γ. The number of spots from wells containing effector cells alone was subtracted from the corresponding wells for each sample to determine the number of tumor-induced spots. Results were expressed as the mean number of spots/well ± SEM. (5 independent experiments).

Blockade of B7-H1 and TGF-β

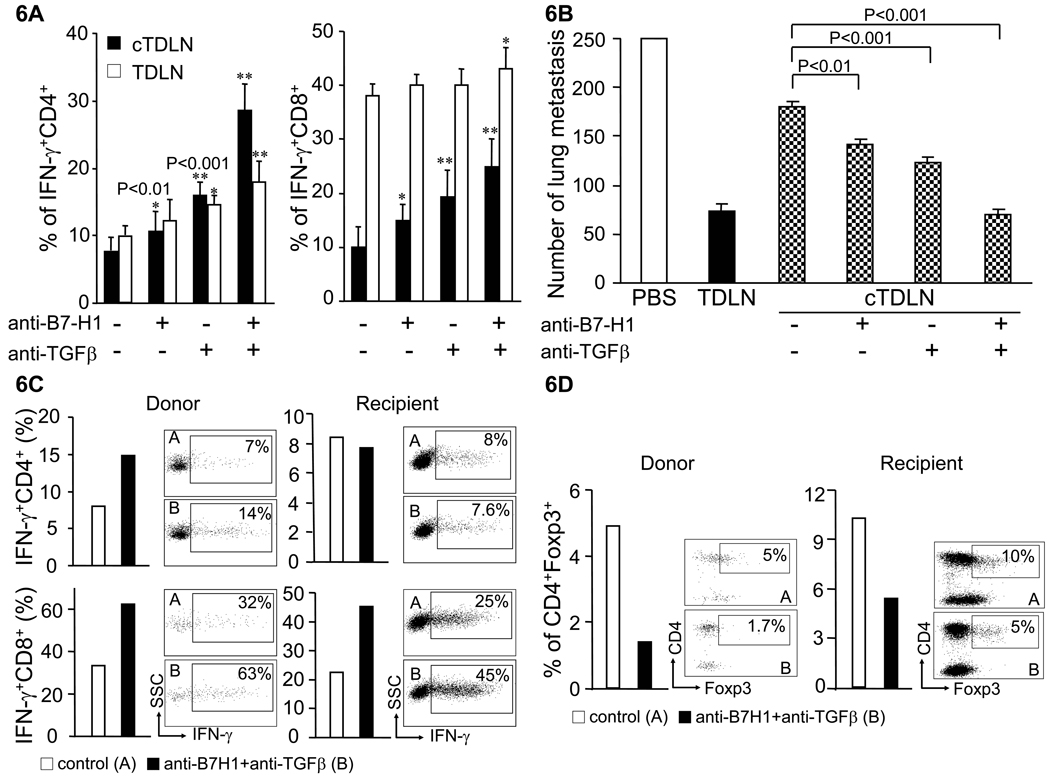

Our studies so far indicate that there is upregulation of B7-H1 and increased numbers Treg cells in cTDLN versus TDLN. We proceeded to examine blockade of B7-H1 as well as TGF-β, an important cytokine in the function and expansion of Treg cells utilizing neutralizing antibodies. Anti-B7-H1 and anti-TGF-β mAbs where added to cTDLN and TDLN cells during in vitro activation and expansion as described in the Methods section. At the end of the culture period, cells were harvested and analyzed for intracytoplasmic IFNγ. As shown in Fig. 6A, the presence of anti-B7-H1 mAb resulted in a significant increase of intracytoplasmic IFNγ for both CD4+ and CD8+ cTDLN cells compared to respective control cultures without antibody; which was not observed for TDLN cells. The presence of anti-TGF-β mAb resulted in a significant increase of intracytoplasmic IFNγ for both TDLN and cTDLN cells; with a significant increase expressed by cTDLN compared to TDLN cells. The presence of both antibodies resulted in a synergistic increase of IFNγ in cTDLN cells that was significantly greater than observed with TDLN cells.

Figure 6.

Blockade of B7-H1 and TGF-β recovered the reduced antitumor activity of cTDLN. B7-H1 and TGF-β were blocked as we described in Materials and Methods. A. Blockade of B7-H1 and TGF-β synergistically increased IFNγ+ T cells in cTDLN and TDLN. The increase in IFN-γ producing T cells was significantly larger in cTDLN than in TDLN. The percent of IFNγ+ T cells was determined by intracellular staining and analyzed by FACS. Results were expressed as the mean percent of IFNγ+ T cells ± SEM. Gated on CD4+ or CD8+CD90+ T cells from 8 independent experiments. (*, p<0.01; **, p<0.001 compared to no blockade). B. Blockade of B7-H1 and TGF-β recovered the reduced antitumor activity of cTDLN as assessed in an adoptive immunotherapy model. Results are representative of 2 independent experiments. 8 × 106 cells were transferred. Five animals were in each group. See Results Section for description of each group. C and D: Blockade of B7-H1 and TGF-β increased IFN-γ+ T cells (C) and decreased CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (D) in cTDLN cells and recipient T cells harvested from the lungs of recipient mice. Expanded cTDLN cells from Thy1.2 C57BL/6 mice were transferred to Thy1.1 mice. Lungs were harvested 8 days after adoptive transfer. Single cell suspension from lungs was stained for intracellular IFN-γ and Foxp3. Donor cells were gated on CD45+CD90.2+ and recipient cells were gated on CD45+CD90.1+.

Based on these results, we examined the in vivo function of cTDLN cells in conjunction with this blockade strategy in our adoptive immunotherapy model. Neutralizing mAb was used during the activation/expansion of cTDLN and also administered exogenously to the adoptive transfer hosts as described in the Methods section. Fig. 6B illustrates that cTDLN cells cultured in the absence of mAbs have deficient antitumor reactivity compared to TDLN cells. However, the presence of anti-B7-H1 or anti-TGF-β during culture and in vivo administration of either mAb partially abrogated the suppressed antitumor reactivity of cTDLN cells. The combination of the two mAbs resulted in complete abrogation of the suppressed antitumor reactivity when compared with TDLN cells. These results were confirmed in a replicate experiment. In another experiment, we found that the antibody blockade needed to be applied both in vitro and in vivo to achieve maximal therapeutic efficacy of cTDLN (data not shown).

Next, as simultaneous blockade of B7-H1 and TGF-β resulted in maximal tumor reduction, we performed additional studies to determine if the in vivo blockade of B7-H1 and TGF-β was affecting the transferred cTDLN or had an effect on host immune cells. Expanded cTDLN cells from Thy1.2 (CD90.2+) mice were transferred to Thy1.1 (CD90.1+) mice bearing lung metastases. Lungs were harvested 8 days after adoptive transfer. Single cell suspensions prepared from lungs were stained for intracellular IFN-γ and Foxp3. Donor cells were gated on CD90.2+ and recipient cells were gated on CD90.1+. Blockade of B7-H1 and TGF-β increased IFN-γ+ T cells (Fig 6C) and decreased CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Fig 6D) in both cTDLN cells and recipient T cells harvested from the lungs of recipient mice.

Discussion

In this study, we have documented that the establishment of visceral or subcutaneous tumors suppress the induction of pre-effector T cells in lymph nodes primed by a subsequent subcutaneous tumor cell inoculation. Based upon previous observations made by our lab, this is not simply a phenomenon of increased tumor burden. We have reported that the establishment of bilateral subcutaneous flank tumors at the same time does not lead to suppressed pre-effector cell induction in TDLN compared with unilateral flank-bearing mice14. In our current model, this suppressed priming is associated with an up-regulation of the co-inhibitor molecule B7-H1 expressed on CD11c+ DC and a parallel up-regulation of PD-1, the counter-receptor of B7-H1, on pre-effector T cells. We found that the up-regulation of PD-1 was maintained after in vitro T activation and expansion in IL-2. Furthermore, the majority of the PD-1+ T cells expressed low levels of CD62L. It has been reported that tumor-specific pre-effector T cells are enriched in CD62Llow T cell population15. The data suggest that the PD-1+CD62Llow T cells may be functionally exhausted tumor specific effector T cells. In line with this concept, these T cells expressed significantly less intracytoplasmic IFNγ compared to effector cells generated in non-tumor bearing hosts.

B7-H1 (aka PD-L1) is a cell-surface glycoprotein of the B7 family that has been described to negatively regulate T cell functions by engagement with PD-1, a CD28 family member receptor. Besides antigen presenting cells, B7-H1 mRNA is found in a variety of non-lymphoid parenchymal organs, including the heart, placenta, skeletal muscle and lung13, 16, 17. B7-H1 co-stimulates T cell growth, selectively induces IL-10 during priming of T cells16, 17 and promotes programmed cell death of effector T cells through ligation of an unknown receptor13. In addition, B7-H1 is thought to inhibit T cell growth and cytokine production by ligation of the PD-1 receptor18, which is expressed on activated T and B cells16, 19. Chen and colleagues reported the presence of B7-H1 protein by immunohistochemistry in a wide range of human cancers20. Tumor-associated B7-H1 induces apoptosis of effector T cells and is thought to contribute to immune evasion by cancers13. Other reports indicating that blockade of B7-H1 enhances tumor immunity, but has no direct effects on tumor cells13, 21, 22. In our model, we found that <10% of MCA 205 tumor cells when freshly harvested expressed B7-H1, although it was inducibly expressed in >96% of tumor cells when cultured with IFNγ in vitro (data not shown). In a study reported by Zou and co-workers, virtually all the DCs isolated from ovarian tumor tissues or tumor-draining lymph nodes expressed high levels of B7-H123. Furthermore, blockade of B7-H1 enhanced DC-mediated T cell activation that was accompanied by downregulation of T cell production of IL-10, with a concomitant upregulation of IL-2 and IFNγ production. Different soluble factors have been implicated in upregulating B7-H1 which include IFNγ13, 21, IL-10 and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)23. In the context of our model, we plan to investigate the possible role of these mediators in the microenvironment of cTDLN.

Dysfunctional DCs that express upregulated B7-H1 may lead to the induction of Treg cells24. We have demonstrated that there is a significantly increased number of Treg cells in cTDLN vs. TDLN. TGF-β is a potent inducer of Treg cells as well25, 26. Furthermore, Tregs can suppress effector function via TGF-β signaling27. One of our hypotheses is that TGF-β is a critical mediator in the suppressive phenomenon observed in the development of cTDLN pre-effector cells. TGF-β may be drived from multiple cells including tumor cells and Treg cells. Indeed, we have found that freshly harvested MCA 205 tumor cells secrete TGF-β in culture when assessed 3 days later (data not shown) giving support to our hypothesis. We found that the suppressed tumor reactivity of cTDLN effector cells can be partially blocked in vitro. The presence of either anti-TGF-β or anti-B7-H1 blocking antibodies during in vitro activation and expansion of cTDLN and TDLN cells resulted in increased intracellular CD4+ and CD8+ IFNγ expression. More importantly, there was a synergistic increase of intracellular IFNγ in the presence of both antibodies that was significantly greater in cTDLN compared to TDLN cells. In adoptive transfer where exogenous blocking antibodies were also administered, the suppression of the antitumor reactivity of the cTDLN effector cells was completely abrogated when compared to TDLN effector cells. Even though MCA 205 secretes TGF-β, we found reduced numbers of host-derived Treg cells in the tumor microenvironment when B7-H1 and TGF-β blockade was performed after adoptive immunotherapy. These studies implicate the role of B7-H1/PD-1 axis and TGF-β (or Treg cells) as important and previously unappreciated synergistic mechanisms in suppressing cellular responses to active immunization in the tumor-bearing host.

Immunotherapy often targets cancer patients with metastatic diseases. The model described in this report is very clinically relevant to the development of effective adoptive cell therapies. Effector cells have to be generated from the cancer-bearing patient. Most animal models have utilized normal, non-tumor bearing hosts as donors for effector cells transferred to secondary recipients. Our current animal model demonstrates that blockade of suppressive mechanisms induced by established tumors can optimize the generation of antitumor reactive effector cells. The use of in vitro blockade can readily be applied in clinical adoptive cellular therapies.

Footnotes

Supported in part by grants from NIH CA82529 and the Gillson Longenbaugh Foundation.

References

- 1.Rosenberg SA, Spiess P, Lafreniere R. A new approach to the adoptive immunotherapy of cancer with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Science (New York, NY. 1986;233:1318–1321. doi: 10.1126/science.3489291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenberg SA, Packard BS, Aebersold PM, et al. Use of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and interleukin-2 in the immunotherapy of patients with metastatic melanoma. A preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:1676–1680. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198812223192527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Yang JC, et al. Adoptive cell transfer therapy following non-myeloablative but lymphodepleting chemotherapy for the treatment of patients with refractory metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2346–2357. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Shelton TE, Even J, Rosenberg SA. Generation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte cultures for use in adoptive transfer therapy for melanoma patients. J Immunother (1997) 2003;26:332–342. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200307000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geiger JD, Wagner PD, Cameron MJ, Shu S, Chang AE. Generation of T-cells reactive to the poorly immunogenic B16-BL6 melanoma with efficacy in the treatment of spontaneous metastases. J Immunother Emphasis Tumor Immunol. 1993;13:153–165. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199304000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shu S, Krinock RA, Matsumura T, et al. Stimulation of tumor-draining lymph node cells with superantigenic staphylococcal toxins leads to the generation of tumor-specific effector T cells. J Immunol. 1994;152:1277–1288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Q, Yu B, Grover AC, Zeng X, Chang AE. Therapeutic effects of tumor reactive CD4+ cells generated from tumor-primed lymph nodes using anti-CD3/anti-CD28 monoclonal antibodies. J Immunother (1997) 2002;25:304–313. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200207000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Q, Carr A, Ito F, Teitz-Tennenbaum S, Chang AE. Polarization effects of 4-1BB during CD28 costimulation in generating tumor-reactive T cells for cancer immunotherapy. Cancer research. 2003;63:2546–2552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang AE, Yoshizawa H, Sakai K, Cameron MJ, Sondak VK, Shu S. Clinical observations on adoptive immunotherapy with vaccine-primed T-lymphocytes secondarily sensitized to tumor in vitro. Cancer research. 1993;53:1043–1050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang AE, Sondak VK, Bishop DK, Nickoloff BJ, Mulligan RC, Mule JJ. Adoptive immunotherapy of cancer with activated lymph node cells primed in vivo with autologous tumor cells transduced with the GM-CSF gene. Hum Gene Ther. 1996;7:773–792. doi: 10.1089/hum.1996.7.6-773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang AE, Aruga A, Cameron MJ, et al. Adoptive immunotherapy with vaccine-primed lymph node cells secondarily activated with anti-CD3 and interleukin-2. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:796–807. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.2.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang AE, Li Q, Jiang G, Sayre DM, Braun TM, Redman BG. Phase II trial of autologous tumor vaccination, anti-CD3-activated vaccine-primed lymphocytes, and interleukin-2 in stage IV renal cell cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:884–890. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dong H, Strome SE, Salomao DR, et al. Tumor-associated B7-H1 promotes T-cell apoptosis: a potential mechanism of immune evasion. Nature medicine. 2002;8:793–800. doi: 10.1038/nm730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sondak VK, Wagner PD, Shu S, Chang AE. Suppressive effects of visceral tumor on the generation of antitumor T cells for adoptive immunotherapy. Arch Surg. 1991;126:442–446. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1991.01410280040005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kagamu H, Shu S. Purification of L-selectin(low) cells promotes the generation of highly potent CD4 antitumor effector T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1998;160:3444–3452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dong H, Zhu G, Tamada K, Chen L. B7-H1, a third member of the B7 family, co-stimulates T-cell proliferation and interleukin-10 secretion. Nature medicine. 1999;5:1365–1369. doi: 10.1038/70932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tamura H, Dong H, Zhu G, et al. B7-H1 costimulation preferentially enhances CD28-independent T-helper cell function. Blood. 2001;97:1809–1816. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.6.1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freeman GJ, Long AJ, Iwai Y, et al. Engagement of the PD-1 immunoinhibitory receptor by a novel B7 family member leads to negative regulation of lymphocyte activation. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2000;192:1027–1034. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.7.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agata Y, Kawasaki A, Nishimura H, et al. Expression of the PD-1 antigen on the surface of stimulated mouse T and B lymphocytes. Int Immunol. 1996;8:765–772. doi: 10.1093/intimm/8.5.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen L. Co-inhibitory molecules of the B7-CD28 family in the control of T-cell immunity. Nature reviews. 2004;4:336–347. doi: 10.1038/nri1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blank C, Brown I, Peterson AC, et al. PD-L1/B7H-1 inhibits the effector phase of tumor rejection by T cell receptor (TCR) transgenic CD8+ T cells. Cancer research. 2004;64:1140–1145. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iwai Y, Ishida M, Tanaka Y, Okazaki T, Honjo T, Minato N. Involvement of PD-L1 on tumor cells in the escape from host immune system and tumor immunotherapy by PD-L1 blockade. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:12293–12297. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192461099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Curiel TJ, Wei S, Dong H, et al. Blockade of B7-H1 improves myeloid dendritic cell-mediated antitumor immunity. Nature medicine. 2003;9:562–567. doi: 10.1038/nm863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zou W. Regulatory T cells, tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nature reviews. 2006;6:295–307. doi: 10.1038/nri1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gorelik L, Flavell RA. Abrogation of TGFbeta signaling in T cells leads to spontaneous T cell differentiation and autoimmune disease. Immunity. 2000;12:171–181. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80170-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gorelik L, Flavell RA. Transforming growth factor-beta in T-cell biology. Nature reviews. 2002;2:46–53. doi: 10.1038/nri704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen ML, Pittet MJ, Gorelik L, et al. Regulatory T cells suppress tumor-specific CD8 T cell cytotoxicity through TGF-beta signals in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:419–424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408197102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]